SpaceX Starship

Starship rocket with the launch tower | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Function | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country of origin |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Size | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Diameter |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch history | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Launch sites |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Starship is a two-stage and super heavy-lift launch vehicle in development by SpaceX, with the main goal of being fully reusable with low operating costs. Generally, the rocket uses liquid oxygen and liquid methane, with its structure divided into two stages: Super Heavy booster and Starship spacecraft. Notably, the latter has four extruding flaps, which are used for its atmospheric entry and descent phase. The spacecraft can be made into many variants, each optimized to serve a particular type of mission. As a direct result, Starship is selected for many space programs, such as the Artemis program or the dearMoon project. It is integral to SpaceX's ambitions of colonizing Mars and making rapid transport between locations on Earth possible.

The launch of Starship begins at either Starbase, Kennedy Space Center, or one of two SpaceX offshore launch platforms. With the rocket pointed upright, the Super Heavy booster fires thirty-three Raptor engines, lifting the whole rocket to space. After separation, the Starship spacecraft fires three of its Raptor Vacuum engines and inserts itself into orbit. Meanwhile, the booster descends through the atmosphere and takes control via its four grid fins. The booster is later caught by the launch tower's arms, which would reposition the booster to the launch mount. At the end of the mission, the Starship spacecraft enters the atmosphere, glides toward the landing site, and lands vertically on a pad.

The rocket was first outlined by SpaceX as early as 2005, with frequent design and name changes as the concept matured. In July 2019, Starhopper, a prototype vehicle with extended fins acting as fixed landing legs, performed a 150 m (490 ft) low altitude test flight under the power of a single Raptor engine. In May 2021, Starship SN15 successfully flew to 10 km (6 mi), transitioning to horizontal free-fall before successfully landing for the first time after four failed attempts by previous prototypes. As of February 2022[update], the Super Heavy BN4 and Starship SN20 are scheduled for the first full-stack flight in early 2022, though this schedule is subjected to change.

Development

Starship's development approach is iterative and incremental,[1] with the owner company SpaceX mostly self-funds the project.[2] The development approach is exemplified by building and launching many prototypes of Starship, which is similar to Falcon 9's reusability development.[3] To be more specific, before launching onto different test flight trajectories, these prototypes are going to be subjected to proof pressure tests and static fires.[4]: 15–19 Due to the company's openness to space news correspondents, these rocket tests have received significant coverage, one of which is spaceflight news site NASASpaceFlight.com.[5]

The reception of Starship development has been mixed among local communities, especially at cities near the Starbase spaceport. Proponents of SpaceX's arrival claimed the company would provide money, education and job opportunities aid to Brownville, Texas, one of the poorest United States's cities.[6] Opponents of the plan, meanwhile, claimed that the company's operation encourages inequality, gentrification,[7] and extensive environmental harm nearby the spaceport.[8]

Concepts

In November 2005, SpaceX first referenced a concept with some capabilities of Starship. The rocket was going to have a larger version of the Merlin engine called Merlin 2, could lift about 100 t (220,000 lb) to low Earth orbit, and was not mentioned to be reusable.[9] The company also had another plan for a rocket called the Mars Colonial Transporter. Although little information had been made public, it was known that the rocket would be powered by the liquid methane fueled Raptor engine. The rocket would have been able to carry one hundred people or 100 t (220,000 lb) of cargo to Mars.[10]

Just before the 67th International Astronautical Congress in September 2016, the first sea-level-optimized Raptor engine was fired.[11] At the presentation, SpaceX CEO and Chief Engineer Elon Musk announced the Interplanetary Transport System. The rocket was to be fully reusable and made of carbon composite, able to put 300 t (660,000 lb) to low Earth orbit. It would use the same Raptor engines to combust liquid methane and oxygen, launching the spacecraft on top into orbit. Then another could be sent up with more fuel, giving the first enough propellant to go on to further destinations.[12] Even though the Interplanetary Transport System had many features to reduce its launch cost, funding for it was not explained satisfactorily. The only mentioned use of the rocket was ferrying crew to Mars for exploration and colonization.[13]

In September 2017, Musk announced a revision to the rocket design and renamed it the Big Falcon Rocket. It was planned to be 106 m (348 ft) tall and 9 m (30 ft) wide, able to launch a reduced 150 t (330,000 lb) to low Earth orbit. The booster engine count was reduced to thirty-one, and the spacecraft to six.[14] Finance for the rocket development was clarified, as the Big Falcon Rocket could clean up space debris, land on the Moon, and travel between locations on Earth. Nevertheless, its ultimate purpose was still to ferry crew to Mars.[15] After the talk, Musk clarified on Reddit that the spacecraft's heat shield was not used to induce lift, but for orientation control.[16]

In September 2018, the dearMoon project funded by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa was announced. Maezawa, along with six to eight other artists, would fly a free-return trajectory around the Moon, and create artworks in the process. There, Musk presented a revised design for the rocket that was 106 m (348 ft) tall and the same 9 m (30 ft) wide. Its spacecraft would have two forward flaps at the top and three aft flaps at the bottom, along with seven Raptor engines. The flaps are used to control the spacecraft's descent and the bottom ones can be used as landing legs.[17] Two months later, in November 2018, the booster was first termed "Super Heavy", and the spacecraft was renamed to "Starship".[18]

Low-altitude flights

The first prototype to run a Raptor engine was the Starhopper.[19] It had three large non-retractable legs[20] and was noticeably shorter than a normal Starship spacecraft. The craft performed two tethered hops in early April 2019 and hopped untethered up to 20–30 m (70–100 ft) two months later, doing a controlled hover at a low speed.[21] In August 2019, the vehicle hopped to 150 m (500 ft) and traveled to the landing pad 100 m (300 ft) away.[22] As of August 2021, the vehicle has been retired and repurposed as a water tank and a mounting point for radio communication, weather, and ground station equipment.[20]

SpaceX then constructed Starship Mk1 and Starship Mk2, located at Starbase and the SpaceX facility in Cocoa, Florida, respectively. In late September 2019, Musk presented more details about the booster, the spacecraft's method to control its descent, its heat shield, orbital refilling feature, and potential destinations outside Mars.[23] The spacecraft design was once again changed, reducing the number of aft flaps from three to two. Musk mentioned the switch of Starship material from carbon composites to stainless steel formally, claiming its lower cost, high melting point, cryogenic temperature strength, and ease of manufacturing.[24] After the presentation, Mk1 was destroyed during a pressure stress test two months later and Mk2 did not fly because the Florida facility was deconstructed throughout 2020.[25][26]

In January 2020, SpaceX bought two drilling rigs from Valaris plc for $3.5 million each during its bankruptcy proceedings and planned to repurpose them as offshore spaceports.[27] After the "Mk" prefix, SpaceX from here named later prototypes with the prefix "SN". No prototypes between SN1 and SN4 flew, as SN1 and SN3 collapsed during a proof pressure test and SN4 exploded after its fifth engine firing.[20] During the interval, the company accelerated the construction of infrastructure at Starbase, which uses large tents, stations, and repurposed intermodal containers. When linked together, these facilities function as a production line, hastening the rocket construction.[28]

In June 2020, SpaceX began construction of an orbital launch pad.[29] Around that time, Starship SN5 was built, the lack of flaps or nose cone giving it a distinctive cylindrical shape. The test vehicle only consisted of one Raptor engine, full-size propellant tanks, and a mass on top. SN5 performed a 150 m (500 ft)-high flight on 5 August 2020, successfully landing on a nearby pad.[30] On 3 September, Starship SN6 with a similar structure to Starship SN5 repeated the hop.[31] A week later, SpaceX stress tested SN7.1 tank that first made use of SAE 304L stainless steel grade, instead of the old SAE 301 stainless steel grade in prior prototypes.[32] In the same September, the company first fired its Raptor Vacuum engine.[33]

High-altitude flights

Animation depicting a successful test flight, following flight profile of SN8 to SN15

SN8 was the first complete Starship prototype and underwent four static fire tests between October and November 2020. The third test ingested fragments of pad material into engine internals, causing an earlier shutdown.[20] The fourth test was successful, and on 9 December 2020 SN8 flew, reaching an altitude of 12.5 km (7.8 mi). However, just before touchdown, an issue related to propellant flow caused the prototype to lose thrust and impact the pad.[34] The test provoked condemnation from FAA Associate Administrator Wayne Monteith, as SpaceX had ignored FAA warnings that weather conditions at the time could have worsened damage from a possible in-flight explosion to nearby homes.[35] Two months later, on 2 February 2021, Starship SN9 launched on an almost identical flight path and crashed on landing.[36]

In March 2021, the company sent a public construction plan to the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which has two sub-orbital launch pads, two orbital launch pads, two landing pads, two test stands, and a large tank farm that stores propellant. The company proposed the incorporation of surrounding Boca Chica Village into a city named Starbase,[37] raising concerns about SpaceX's authority, power, and potential abuse for eviction.[38] On 3 March 2021, after an initially aborted launch, Starship SN10 traveled the same flight path. The vehicle then landed hard and crushed its landing legs. Minutes later, SN10 exploded, due to a propellant tank rupture.[39]

After approval from the FAA,[40] on 30 March 2021, Starship SN11 flew into thick fog along the same flight path. The vehicle exploded during descent, scattering debris up to 8 km (5 mi) away.[41] In early April 2021, the first tank was placed into the fuel farm for the first orbital launch pad.[29] Around the same time, despite a few earlier misgivings about its complexity,[42] NASA selected Starship HLS as the crewed lunar lander.[43] The decision was disputed by Blue Origin and sparked a six-month-long dispute, titled Blue Origin v. United States & Space Exploration Technologies Corp.[44] Returning to Starbase, Starship SN12, SN13, and SN14 were not fully assembled, and Starship SN15 was selected to fly instead. On 5 May 2021, SN15 flew, did the same maneuvers as older prototypes and landed, completing the first successful mission.[45]

Planned orbital launches

In July 2021, Super Heavy BN3 first fired three of its engines.[46] Super Heavy BN4 was the first that can mate to Starships, while Starship SN20 was the first to feature a body-tall heat shield, mostly made of black hexagonal heat tiles. A month later, Starship SN20 was stacked atop of Super Heavy BN4, the first pair of vehicles to be so stacked.[47] In October 2021, the catching mechanical arm was installed onto the first launch tower, forming the recovery system, and the last tank insulation cover was installed, marking the completion of the first tank farm.[29] On 26 November 2021, a day after Thanksgiving in the United States, Musk sent an internal email to all SpaceX employees saying that the Raptor engine's production line was not sufficiently mature, thus creating a risk of bankruptcy for the company.[48]

Two weeks later, just north of Launch Complex 39B, NASA announced the new Launch Complex 49 that will launch Starship at the Kennedy Space Center.[49] In February 2022, Musk gave a presentation on Starship development at Starbase. There, he clarified much of the information provided in the past, as well as giving updates on Starship HLS, Raptor engines, the environmental assessment of Starbase, and a reopening of the Florida facility.[50]

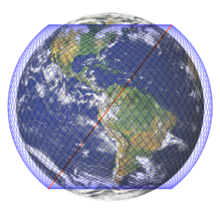

SpaceX explained the planned trajectory of the first orbital flight of the Starship system in a report sent to the Federal Communications Commission. The rocket is planned to launch from Starbase, then Super Heavy will separate and perform a soft water landing around 30 km (20 mi) from the Texan shoreline. The spacecraft will continue flying with its ground track passing through the Straits of Florida, and then softly land in the Pacific Ocean around 100 km (60 mi) northwest of Kauai in the Hawaiian Islands. The whole spaceflight will last ninety minutes.[51][52]

Description

Starship is designed to be a fully reusable orbital rocket, with the aim of reducing launch costs drastically.[53] One launch may deliver more than 100 t (220,000 lb) to low Earth orbit, which would formally classify the rocket as a super heavy-lift launch vehicle.[54] When stacked and fueled, Starship may be about 5,000 t (11,000,000 lb) by mass,[57] 9 m (30 ft) wide,[58] and 120 m (390 ft) high,[59] taller than the Saturn V by 9 m (30 ft).[60] The rocket will consist of a Super Heavy first stage or booster and a Starship second stage or spacecraft.[61] powered by many Raptor and Raptor Vacuum engines.[55] These rocket stages' reusability and stainless-steel construction has influenced other rockets such as the Terran R[62] and Project Jarvis.[63]

Raptor engine

Raptor is a family of rocket engines used in the Starship rocket, combusting liquid oxygen and methane in a full-flow staged combustion cycle. The whole family uses a new alloy and can obtain 300 bar (4,400 psi) inside the main combustion chamber. These engines can fire many times,[64] with their nozzles cooled by surrounding running propellant, called regenerative cooling.[55] In the future, the engine family may be mass-produced,[64] costing about $230,000 per engine and $100 per kilonewton.[55]

The Raptor family is the only full-flow staged combustion cycle engine currently in production. In the past, the Soviet Union and the United States tried to construct such an engine, but both products have never been put in use.[64] A general full-flow staged combustion cycle engine has two preburners connected to their matching turbopumps.[65] One of the preburners is fed with an oxygen-rich mixture and the other is fed with a propellant-rich mixture, combusting a small amount to spin the matching turbines. The cycle then feeds all gaseous propellant mixture into the combustion chamber, unlike other engine cycles that waste some propellant. This increases the engine's chamber pressure, making more thrust and being more efficient overall.[64]

Methane was chosen for the Raptor engines since it may be cheaper, does not accumulate soot,[64] and can be produced on Mars via the Sabatier reaction,[66] among other reasons.[64] The engines run at an oxygen to methane mass ratio of 3.6 : 1,[67] as combusting a stoichiometric mixture of 4 : 1 would overheat and damage them.[55] The exhaust contains carbon dioxide and water, with a trace amount of carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. The plume stretches about 65 m (213 ft) at full power,[67] longer than the Starship spacecraft by about 15 m (49 ft).[68] When clustered inside a rocket stage, the inner engines' plumes do not interact with the air right away, so the cluster's plume may be much longer.[67]

SpaceX builds multiple other variants of Raptor. The company specifies the Raptor engine has a ratio of throat area to exit area of 1:34.[67] Another is the Raptor Vacuum, designed to be fired in space. It is equipped with a nozzle extension made from brazed steel tubes, increasing the throat area to exit area to 1:90 and specific impulse or fuel efficiency to 380 seconds. The Raptor 2 is the next generation in the family; the engine may produce 2.3 MN (520,000 lbf) of thrust, with its specific impulse reduced by 3 seconds.[55] The new generation of Raptor simplified the design of the earlier version.[50] In the long term, SpaceX plans to make three variants of Raptor: sea level-optimized engine with gimbaled thrust, sea level-optimized engine without gimbaled thrust, and vacuum-optimized engine without gimbaled thrust.[55]

Super Heavy booster

Super Heavy is a booster or first stage, located at the bottom of the rocket. The booster measures 70 m (230 ft) tall,[58] housing up to thirty-three sea level-optimized Raptor engines. The engine cluster may be more than twice as powerful as the Saturn V.[69] The booster's tanks can hold 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb) of propellant, consisting of 2,800 t (6,200,000 lb) of liquid oxygen and 800 t (1,800,000 lb) of liquid methane.[70] Without propellant, Super Heavy's dry mass is estimated to range between 160 t (350,000 lb) to 200 t (440,000 lb). Of which, the tanks weigh 80 t (180,000 lb), the interstage between the booster and spacecraft weigh 20 t (44,000 lb), and all the engines and mounts weigh 2 t (4,400 lb).[55]

The booster is equipped with four grid fins, each with a mass of 3 t (6,600 lb). These grid fins are not spaced evenly for obtaining more pitch control and can only rotate in the roll axis.[55] They may control the booster's descent and work as a mounting point for a touchdown into the tower's mechanical arms. Though catching Super Heavy requires great precision, this may reduce the turnaround time after landing and enable more frequent launches.[71] To control the booster's orientation, it may fire cold gas thrusters fed by evaporated propellant inside tanks. While Super Heavy and Starship are attached in space, the booster can move its engines and separates from the spacecraft.[55]

Starship spacecraft

Starship is a spacecraft and a second stage, located at the top of the booster. The spacecraft is 50 m (160 ft) tall,[58] with a dry mass of less than 100 t (220,000 lb).[55] By refueling the Starship spacecraft using tanker spacecraft, Starship may carry payloads and astronauts to higher Earth orbits, the Moon, Mars, and other destinations in the Solar System.[61] The spacecraft has two main and two header tanks,[72] for a total of 1,200 t (2,600,000 lb) capacity.[56] Each of its main and header tanks hold a type of propellant, either liquid oxygen or methane, with the header tanks being reserved to flip and land the spacecraft.[73] At the bottom of Starship are six Raptor engines, with three operating in the atmosphere while the other three Raptor Vacuum may run in space.[55]

The spacecraft has four body flaps to control the spacecraft's falling velocity and orientation, with two forward flaps mounted near the nose cone and two aft flaps mounted near the bottom.[20] The hinges that mount them are sealed with metal, as they are the most easily damaged part during reentry.[55] Starship's heat shield is designed to be used multiple times with no maintenance between flights.[53] It is composed of thousands of hexagonal tiles,[47] each mounted and spaced to counteract expansion due to heat.[53] The shape of these tiles prevents hot plasma from causing damage, allowing it to withstand temperatures of 1,400 °C (2,600 °F).[74] Starship payload volume may be as large as 1,000 m3 (35,000 cu ft), far larger than any other spacecraft.[54] The spacecraft nose cone as of August 2021 is made from two rows of stretch-formed steel.[55]

Variants

The cargo Starship spacecraft variant may feature a large door replacing conventional payload fairings, which can launch, store, capture, and return payloads. The payload door would be closed during launch, opened to release its payload once in orbit, and closed again during reentry. It may be possible to mount the payload on the inside of the payload bay's sidewalls using trunnions, more suitable for payloads on ride-share missions. Payloads may be integrated into a vertical rocket inside temperature-controlled, ISO class 8 clean air.[75]

The crew variant can be adapted for missions to the Moon, Mars, point-to-point flights, and other destinations. Each spacecraft can carry one hundred people, with "private cabins, large communal areas, centralized storage, solar storm shelters, and a viewing gallery".[61] Starship's life-support system is expected to be closed, where resources are constantly recycled. Other than that, little information about it is provided to the public.[76]

The tanker variant can be used to refuel another spacecraft in orbit. According to Musk, up to seven launches of the tanker are needed to send a spacecraft to the Moon.[54] The concept was detailed by Musk in September 2019, by docking the ends of both spacecraft to each other. They then accelerate slightly toward the tanker using control thrusters, settling propellant to the fueled Starship.[56] In October 2020, NASA awarded SpaceX US$53.2 million to conduct a large-scale flight demonstration, transferring 10 t (22,000 lb) of propellant between the tanks of two Starship spacecraft.[77]

Starship HLS is a crewed lunar lander variant of the Starship spacecraft for NASA's Artemis program. The lunar lander may have windows and airlocks near the top,[78] along with an elevator and a set of thrusters to land on the Moon's surface.[79] The lunar lander may be able to carry a large amount of payload between outer space and the Moon. On an Artemis mission, it may launch ahead of the crew by up to a hundred days, accompanied with many other launches of refueling Starship tankers. Another variant of the lunar lander may be used for the Commercial Lunar Payload Services program,[78] where scientific, explorational, and commercial payloads are tasked with being sent to the Moon.[80]

Launch profile

Before launch, Super Heavy and Starship are stacked onto a launch mount and loaded with propellant.[29] When the rocket launches at Starbase, it may make more than 115 dBA at up to a 3.7 km (2.3 mi) radius, and up to 90 dBA throughout most of Brownsville, a nearby city,[81] comparable to a lawnmower.[82] For providing context, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration defines 115 dB as the upper limit for exposure within 15 minutes, beyond which hearing damage may occur.[81]

Then, after some time during launch, the stages separate via the conservation of angular momentum.[55] The booster flips its orientation and turns on its center engine cluster returning to the launch site, followed by a controlled descent, and a landing burn. It is then caught by a pair of mechanical arms, arresting any remaining velocity, and repositioning the booster onto the mount, allowing another launch cycle to begin.[83] Super Heavy would have 20 t (44,000 lb) of propellant left after launching and landing.[55] Landings of the booster may be quieter than launches, as residents of Brownsville may experience noise levels in the range of 60 dBA,[81] comparable to the volume of a human conversation.[84]

Meanwhile, the Starship spacecraft accelerates to orbital velocity and circularizes its orbit.[51] There, the spacecraft may be refueled by the Starship tanker variants, by docking both spacecraft to each other. Both then accelerate slightly toward the tanker using control thrusters, settling propellant into the fueled Starship. The refueled Starship then fires its engines and coasts to the destination.[56]

For landing on bodies without an atmosphere like the Moon, Starship turns on its engines and thrusters to slow down and land.[75] For other bodies with an atmosphere like Mars, Starship slows down by entering the atmosphere, protected by a heat shield.[47] After atmospheric entry, Starship performs a belly flop maneuver, defined in a whitepaper as the control of its surface area, leading to the control of aerodynamic drag and terminal velocity.[85] Tim Dodd, American space and science communicator, analyzed the maneuver and highlighted its large propellant saving compared to the Falcon 9 first stage's landing.[86]

During landing, both liquid methane and oxygen header tank are used to feed the Raptor engines.[72] A pseudospectral optimal control algorithm predicted that the landing flip may make Starship overshoot the landing point by 100 m (300 ft). The simulation further predicted that the spacecraft would intentionally tilt 20° further from the ground's normal line and then reduce to zero on touchdown.[85] The spacecraft's landing may make more than 60 dBA at Brownsville, similar to Super Heavy landing's noise level and lower than rocket liftoff.[81]

Applications

Starship launch cost estimates vary widely, ranging from Musk's $2 million per launch to a satellite market analyst's $10 million. It is hoped that this lower launch cost would be accomplished by Starship's reusability, expanding space access to more types of payloads and entities.[87] On the contrary, Pierre Lionnet, director of research at Eurospace, said that launch cost may not play a key role in certain science payloads.[88]

Satellites and probes

Starship may enable the launching of larger space telescopes, such as the Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission that can directly image planets outside the Solar System.[87] Some planetary science researchers started incorporating Starship into their projects, citing low launch cost and high launch capacity.[89] An analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute think-tank wrote possible military-use cases of Starship. One of them is the deployment of military satellites, replacing ones destroyed by anti-satellite weapons. Another is the launch of many reconnaissance satellites to fill gaps if larger satellites in a higher orbit were destroyed.[90] Waleed Abdalati, a former NASA Chief Scientist, said the rocket may enable recovery of space debris, which are defunct artificial objects in space.[88]

Starship is intended to launch the next generation of SpaceX's Starlink communication satellites.[91] A space analyst at Morgan Stanley, a financial services company, said that both Starship and Starlink are very intertwined with each other. This is because improvements in launch capacity and cost aid Starlink satellite launches and Starlink profits can be fed back into Starship development.[92] A single orbital launch of Starship could place up to four hundred Starlink satellites into orbit, whereas the Falcon 9 flights in 2019 and 2020 launched a maximum of 60 satellites per flight.[93]

According to NASA's Ames Research Center, since Starship may have a large capacity, it may bring heavy machinery to destinations in space, such as drilling rigs on the surface of bodies. The mission may enable much more comprehensive research of their interiors and underground resources, which earlier rockets would not be able to do so at a reasonable cost.[54] Starship may enable large experiments and sample-return missions of Moon and Mars rock. These missions could be integrated into SpaceX's test landings of the spacecraft[88] and designed to go to locations of interest. Such a mission may answer many unsolved problems in astronomy, such as past volcanism on the Moon or extraterrestrial life.[54]

A scouting mission proposed to deliver a probe for the Neptunian system, with a lander on its moon Triton. The probe would be equipped with a telescope to study the outer Solar System and exoplanets in other stars. Another was proposed to launch a space probe orbiting around Io, a moon of Jupiter, which is difficult because of the mission's demand for shielding from intense radiation and large delta-v budget or range. Even further, the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research, who experiment with using solar sails to travel between the stars, proposed a mission riding on a Starship cruising to Mars.[54]

Human travel

One potential use for Starship is space tourism. An example is the dearMoon project announced by Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa. The project consists of a flight around the Moon with Starship, with its crew consisting of Maezawa and eight others. The other crews are selected via video submissions with applicants ranging from dancers, actors, photographers, artists, to athletes.[94] Another example is the Polaris program announced by Jared Issacman, Mission Commander for the Inspiration4 mission, aimed to raise funds for St. Jude Children's Research Hospital.[95]

The spacecraft may host point-to-point flights – coined "Earth to Earth" by SpaceX – by traveling between spaceports on Earth. For example, via this mode of transport, a flight between New York City and Shanghai is estimated to take about 39 minutes. SpaceX president and chief operating officer, Gwynne Shotwell, predicted it could become cost-competitive with business class travel.[96] John Logsdon, an academic on space policy and history, said point-to-point travel would have a high acceleration, thus making it impractical for civilians.[97] The Rocket Cargo program by the United States Space Force as of December 2021 is researching this mode of transport.[98]

Space colonization

SpaceX has said its goal is to colonize Mars for the long-term survival of the human species.[99] Musk himself has been pursuing the goal since 2001 with the Mars Oasis program, where a rocket would launch a greenhouse to Mars. At the time, its purpose was to stimulate the space market and increase NASA's budget.[100] The final possible goal of the program is to send a million people to Mars by 2050, with a thousand Starships sent during a Mars launch window.[101]

Although Musk said that the company may land the first humans on Mars before 2026, the goal is considered optimistic. Greg Autry, a space policy expert, said that such a mission might not happen before 2029, even with aid from NASA.[99] Likewise, SpaceX rated Starship HLS's propulsion, communications, and life-support system as technology readiness level 6 and 7 respectively, meaning the technology has been shown by prototypes. Super Heavy booster and propellant fueling function were rated technology readiness levels 4 and 5 respectively, meaning the technology has only reached validated status.[102]: 52 SpaceX has not detailed plans for life-support systems, radiation protection, and in situ resource utilization, even though they are essential for colonizing space.[76]

The Sabatier reaction may be used to create liquid methane and liquid oxygen on Mars in a power-to-gas plant, fueling return missions.[66] The reaction works by exposing carbon dioxide and hydrogen to a catalyst at temperatures above 375 °C (700 °F) at high pressure. Carbon dioxide and hydrogen gas can be obtained from Mars's atmosphere and ice, while the catalyst used may be nickel or ruthenium. The reaction is very energy inefficient, requiring an extensive thermal management system, and the resultant methane must be purified before use.[103]

Facilities

SpaceX is building many launch sites, including Launch Complex 39A of the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, its offshore platforms, and the Starbase facility.[93] Starbase, located east of Brownsville in southern Texas, serves as Starship's primary spaceport, factory, and host of all Starship test flights as of December 2021.[54] As of August 2021, Shyamal Patel is the Director of Starship Operations.[55]

Starbase

Starbase consists of a manufacturing facility and launch site[104] at Boca Chica, Texas. Both operate around the clock,[28] with at most 450 full-time employees who may be onsite.[105]: 24 The site hosted the STARGATE facility of the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. SpaceX uses part of the facility for Starship development, while most is used by the university for the study and research of space technologies.[106] The site is planned to consist of two launch complexes, two payload processing facilities, a desalination plant, a natural gas power plant, a natural gas purifier, a liquefier, and a solar farm.[105]: 30–34

Manufacturing of the Starship rocket starts with rolls of stainless steel[28] of SAE 304L grade.[32] These rolls are unrolled, cut, and welded along the cut edge to create a cylinder. Each of these cylinders is 9 m (30 ft) in diameter, 2 m (7 ft) in height, and around 1,600 kg (4,000 lb) in mass. To make the outer layer of the Starship spacecraft, seventeen of these cylinders and nose cones are stacked and welded along their edges. Inside the body are many domes, separating liquid methane and oxygen tanks at high pressure. These domes are made by robots and welded at the rate of ten minutes per seam. Afterwards, they are inspected by an X-ray machine.[28]

A launch complex at Starbase consists of a launch pad, a launch tower, and a tank farm. The launch pad has a water sound suppression system and twenty clamps, holding down the booster until launch.[29] The launch tower consists of steel truss sections, a lightning rod on top,[107] and a pair of mechanical arms that may catch and recover the booster.[108] Each tank farm consists of eight tanks: three for liquid oxygen, two for liquid methane, two for liquid nitrogen, and one for water.[29] Other tanks surrounding the area contain all other commodities, such as methane, oxygen, nitrogen, helium, and hydraulic fluid.[105]: 13

Others

Phobos and Deimos are offshore platforms under construction for launching Starship at sea. They were previously Valaris 8501 and Valaris 8500 respectively—oil drilling rigs owned by Valaris plc.[27] Their main decks measure 78 m (260 ft) long by 73 m (240 ft) wide, with a helicopter deck on top of one of their corners. Four columns extrude at each corner at the bottom, measuring 15 m (49 ft) long and 14 m (46 ft) wide each.[109]

The Kennedy Space Center is planned to have Starship launch pads at Launch Complex 39A and Launch Complex 49, north of Launch Complex 39C. Launch Complex 39A had hosted Saturn V and Space Shuttle flights, while Launch Complex 39C was planned to be built north of Launch Complex 39A and 39B to support Saturn V flights. Launch Complex 49 has been under consideration since at least 2014 and as of December 2021, under environmental review by NASA. If either launch site is to be built, Starship may need space inside the Vehicle Assembly Building. The building is divided into four high bays, with three reserved for the Space Launch System. The remaining high bay may be used to build Super Heavy and Starship, with both stages stacked at the launch pad.[110]

The Rocket Development facility at McGregor, Texas is used to test Raptor engines before delivery to Starbase. It has a vertical test stand for firing the Raptor engine, along with a horizontal test stand for firing Raptor and Raptor Vacuum. The facility has other stands for testing Falcon rocket's stages, Merlin engines, and future reaction control thrusters on Starship. In the past, the McGregor facility hosted test flights of Grasshopper and F9R Dev1, the first stages used for landing tests. SpaceX's main factory at Hawthorne, California is producing the Raptor Vacuum and experimental designs. Another factory near the McGregor facility is under construction as of September 2021, which will make Raptor 2 engines.[111]

Another SpaceX facility at Cocoa, Florida near the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, in the past hosted the construction of Starship Mk2, a prototype built in competition with Starbase. As of February 2022, the facility has been processing raw materials to make the spacecraft's heat shield. Nearby the facility are hangars for Falcon rocket boosters and a large swath of land, dedicated for another Starship launch complex. The Florida facility's construction is motivated partly by the uncertain environmental review result at Starbase.[112]

References

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (28 September 2019). "Elon Musk Sets Out SpaceX Starship's Ambitious Launch Timeline". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 7 April 2020. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (16 April 2021). "NASA selects SpaceX as its sole provider for a lunar lander". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ "Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Launch Vehicle Program at the SpaceX Boca Chica Launch Site in Cameron County, Texas" (PDF). FAA. September 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (9 April 2021). "$200,000 streaming rigs and millions of views: inside the cottage industry popping up around SpaceX". CNN. Archived from the original on 22 June 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Fouriezos, Nick (9 March 2022). "SpaceX launches rockets from one of America's poorest areas. Will Elon Musk bring prosperity?". USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Solomon, Dan (27 December 2021). "Will Elon Musk Austin-ify Brownsville?". Texas Monthly. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Grush, Loren (21 October 2021). "Critics and supporters come out in force to discuss SpaceX's plans to launch from South Texas". The Verge. Archived from the original on 18 November 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (14 November 2005). "Big plans for SpaceX". The Space Review. Archived from the original on 24 November 2005. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Burgess, Matt (19 September 2016). "Mars and beyond: Elon Musk teases his plans for interplanetary travel". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 27 February 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (26 September 2016). "SpaceX performs first test of Raptor engine". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (28 September 2016). "Musk's Mars moment: Audacity, madness, brilliance—or maybe all three". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (27 September 2016). "Elon Musk's Plan: Get Humans to Mars, and Beyond". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (29 September 2017). "Musk revises his Mars ambitions, and they seem a little bit more real". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 23 November 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Baidawi, Adam; Chang, Kenneth (28 September 2017). "Elon Musk's Mars Vision: A One-Size-Fits-All Rocket. A Very Big One". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Liptak, Andrew (15 October 2017). "Here's what Elon Musk revealed about his Mars rocket during his Reddit AMA". The Verge. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Foust, Jeff (18 September 2018). "SpaceX signs up Japanese billionaire for circumlunar BFR flight". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ "Elon Musk renames his BFR spacecraft Starship". BBC News. 20 November 2018. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (28 August 2019). "Starhopper aces test, sets up full-scale prototype flights this year". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Kanayama, Lee; Beil, Adrian (28 August 2021). "SpaceX continues forward progress with Starship on Starhopper anniversary". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (26 July 2019). "SpaceX's Starship prototype has taken flight for the first time". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Harwood, William (27 August 2019). "SpaceX launches "Starhopper" on dramatic test flight". CBS News. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (29 September 2019). "Elon Musk says SpaceX Starship rocket could reach orbit within 6 months". CNET. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (29 September 2019). "SpaceX Unveils Silvery Vision to Mars: 'It's Basically an I.C.B.M. That Lands'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Grush, Loren (20 November 2019). "SpaceX's prototype Starship rocket partially bursts during testing in Texas". The Verge. Archived from the original on 14 November 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Bergeron, Julia (6 April 2021). "New permits shed light on activity at SpaceX's Cidco and Roberts Road facilities". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ^ a b Burghardt, Thomas (19 January 2021). "SpaceX acquires former oil rigs to serve as floating Starship spaceports". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d Berger, Eric (5 March 2020). "Inside Elon Musk's plan to build one Starship a week—and settle Mars". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Weber, Ryan (31 October 2021). "Major elements of Starship Orbital Launch Pad in place as launch readiness draws nearer". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 5 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Mack, Eric (4 August 2020). "SpaceX Starship prototype takes big step toward Mars with first tiny 'hop'". CNET. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (3 September 2020). "SpaceX launches and lands another Starship prototype, the second flight test in under a month". CNBC. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (6 September 2020). "Following Starship SN6's hop, SN7.1 prepares to pop". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Kooser, Amanda (26 September 2020). "Watch SpaceX fire up Starship's furious new Raptor Vacuum engine". CNET. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Wattles, Jackie (10 December 2020). "Space X's Mars prototype rocket exploded yesterday. Here's what happened on the flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 10 December 2020.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (15 June 2021). "SpaceX ignored last-minute warnings from the FAA before December Starship launch". The Verge. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Mack, Eric (2 February 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN9 flies high, explodes on landing just like SN8". CNET. Archived from the original on 18 September 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (8 March 2021). "SpaceX reveals the grand extent of its starport plans in South Texas". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Keates, Nancy; Maremont, Mark (7 May 2021). "Elon Musk's SpaceX Is Buying Up a Texas Village. Homeowners Cry Foul". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (3 March 2021). "SpaceX Mars Rocket Prototype Explodes, but This Time It Lands First". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (30 March 2021). "Watch SpaceX's launch and attempted landing of Starship prototype rocket SN11". CNBC. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Mack, Eric (30 March 2021). "SpaceX Starship SN11 test flight flies high and explodes in the fog". CNET. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Clark, Stephen. "NASA identifies risks in SpaceX's Starship lunar lander proposal – Spaceflight Now". Archived from the original on 3 February 2021. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ Roulette, Joey (30 April 2021). "NASA suspends SpaceX's $2.9 billion moon lander contract after rivals protest". The Verge. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (4 November 2021). "Bezos' Blue Origin loses NASA lawsuit over SpaceX $2.9 billion lunar lander contract". CNBC. Archived from the original on 4 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Mack, Eric (7 May 2021). "SpaceX's Mars prototype rocket, Starship SN15, might fly again soon". CNET. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (23 July 2021). "Rocket Report: Super Heavy lights up, China tries to recover a fairing". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ a b c Sheetz, Michael (6 August 2021). "Musk: 'Dream come true' to see fully stacked SpaceX Starship rocket during prep for orbital launch". CNBC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (30 November 2021). "Elon Musk tells SpaceX employees that Starship engine crisis is creating a 'risk of bankruptcy'". CNBC. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ Costa, Jason (15 December 2021). "NASA Conducts Environmental Assessment, Practices Responsible Growth". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (11 February 2022). "SpaceX considers shifting Starship testing to Florida". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 10 March 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Starship Orbital – First Flight FCC Exhibit". SpaceX (PDF). 13 May 2021. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (13 May 2021). "SpaceX reveals first orbital Starship flight plan, launching from Texas and returning near Hawaii". CNBC. Archived from the original on 1 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Inman, Jennifer Ann; Horvath, Thomas J.; Scott, Carey Fulton (24 August 2021). SCIFLI Starship Reentry Observation (SSRO) ACO (SpaceX Starship). NASA. p. 2. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g O'Callaghan, Jonathan (7 December 2021). "How SpaceX's massive Starship rocket might unlock the solar system—and beyond". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Sesnic, Trevor (11 August 2021). "Starbase Tour and Interview with Elon Musk". The Everyday Astronaut (Interview). Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d Lawler, Richard (29 September 2019). "SpaceX's plan for in-orbit Starship refueling: a second Starship". Engadget. Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ Super Heavy dry mass: 160 t (350,000 lb) – 200 t (440,000 lb)[55]

Starship dry mass: <100 t (220,000 lb)[55]

Super Heavy propellant mass: 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb)[55]

Starship propellant mass: 1,200 t (2,600,000 lb)[56]

Total of these masses are about 5,000 t (11,000,000 lb). - ^ a b c d e Dvorsky, George (6 August 2021). "SpaceX Starship Stacking Produces the Tallest Rocket Ever Built". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Super Heavy is 70 m (230 ft) tall and Starship spacecraft is 50 m (160 ft) tall,[58] sum up to 120 m (390 ft).

- ^ Technical information summary AS-501 Apollo Saturn V flight vehicle (PDF). NASA (Report). Marshall Space Flight Center. 15 September 1967. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Berger, Eric (31 March 2020). "SpaceX releases a Payload User's Guide for its Starship rocket". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (8 June 2021). "Relativity has a bold plan to take on SpaceX, and investors are buying it". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (27 July 2021). "Blue Origin has a secret project named "Jarvis" to compete with SpaceX". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f O'Callaghan, Jonathan (31 July 2019). "The wild physics of Elon Musk's methane-guzzling super-rocket". Wired UK. Archived from the original on 22 February 2021. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- ^ "New rocket engine combustion cycle technology testing reaches 100% power level". NASA. 18 July 2006. Archived from the original on 8 March 2016. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Sommerlad, Joe (28 May 2021). "Elon Musk reveals Starship progress ahead of first orbital flight of Mars-bound craft". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 August 2021. Retrieved 4 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Exhaust Plume Calculations for SpaceX Raptor Booster Engine" (PDF). Federal Aviation Administration (PDF). Sierra Engineering & Software, Inc. 18 June 2019. pp. 1–2, 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 October 2021. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ Starship is 50 m (160 ft) tall.[58] Subtracting the plume length and Starship height returns 15 m (49 ft).

- ^ Berger, Eric (2 August 2021). "SpaceX installed 29 Raptor engines on a Super Heavy rocket last night". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ 78% of 3,600 t (7,900,000 lb) is 2,800 t (6,200,000 lb) of liquid oxygen

- ^ Fingas, Jon (3 January 2021). "SpaceX will try to 'catch' its Super Heavy rocket using the launch tower". Engadget. Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2022.

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (28 September 2020). "Starship SN8 prepares for test series - First sighting of Super Heavy". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Kanayama, Lee; Beil, Adrian (28 August 2021). "SpaceX continues forward progress with Starship on Starhopper anniversary". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 31 August 2021. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- ^ Torbet, Georgina (29 March 2019). "SpaceX's Hexagon Heat Shield Tiles Take on an Industrial Flamethrower". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ a b Foust, Jeff (6 January 2021). "SpaceX, Blue Origin, and Dynetics Compete to Build the Next Moon Lander". IEEE Spectrum. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 29 November 2021.

- ^ a b Grush, Loren (4 October 2019). "Elon Musk's future Starship updates could use more details on human health and survival". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Hall, Loura (13 October 2020). "2020 NASA Tipping Point Selections". NASA. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b Burghardt, Thomas (20 April 2021). "After NASA taps SpaceX's Starship for first Artemis landings, agency looks to on-ramp future vehicles". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (4 August 2021). "Bezos' Blue Origin calls Musk's Starship 'immensely complex & high risk' for NASA moon missions". CNBC. Archived from the original on 4 August 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Dunbar, Brian (18 November 2019). "Commercial Lunar Payload Services Overview". NASA. Archived from the original on 30 December 2021. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Starship rocket noise assessment for flight and test operations at the Boca Chica launch facility" (PDF). KBR. December 2020. pp. 3–5, 17, 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 October 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Harmful Noise Levels". University of Michigan School of Public Health. 2 December 2020. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (4 January 2021). "SpaceX may try to catch a falling rocket with a launch tower". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 5 July 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ "What Noises Cause Hearing Loss?". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 October 2019. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sagliano, Marco; Seelbinder, David; Theil, Stephan (25 June 2021). SPARTAN: Rapid Trajectory Analysis via Pseudospectral Methods (PDF). 8th International Conference on Astrodynamics Tools and Techniques. German Aerospace Center. Bremen. pp. 10–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ DeSisto, Austin (23 April 2021). "Starship and its Belly Flop Maneuver". The Everyday Astronaut. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ a b Mann, Adam (20 May 2020). "SpaceX now dominates rocket flight, bringing big benefits—and risks—to NASA". Science (news). doi:10.1126/science.abc9093. Archived from the original on 7 November 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ a b c Bender, Maddie (16 September 2021). "SpaceX's Starship Could Rocket-Boost Research in Space". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 26 October 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (1 December 2021). "Planetary scientists are starting to get stirred up by Starship's potential". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ Davis, Malcolm (17 May 2021). "SpaceX's reusable rocket technology will have implications for Australia". The Strategist. Archived from the original on 11 September 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2021.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (19 August 2021). "SpaceX adding capabilities to Starlink internet satellites, plans to launch them with Starship". CNBC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (19 October 2021). "Morgan Stanley says SpaceX's Starship may 'transform investor expectations' about space". CNBC. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sheetz, Michael (1 September 2020). "Elon Musk says SpaceX's Starship rocket will launch "hundreds of missions" before flying people". CNBC. Archived from the original on 2 September 2020. Retrieved 2 September 2020.

- ^ Ryan, Jackson (15 July 2021). "SpaceX moon mission billionaire reveals who might get a ticket to ride Starship". CNET. Archived from the original on 13 January 2022. Retrieved 13 January 2022.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (14 February 2022). "Billionaire astronaut Jared Isaacman buys more private SpaceX flights, including one on Starship". CNBC. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- ^ Sheetz, Michael (18 March 2019). "Super fast travel using outer space could be US$20 billion market, disrupting airlines, UBS predicts". CNBC. Archived from the original on 29 October 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Ferris, Robert (29 September 2017). "Space expert calls Elon Musk's plan to fly people from New York to Shanghai in 39 minutes 'extremely unrealistic'". CNBC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ Erwin, Sandra (29 December 2021). "Blue Origin joins U.S. military 'rocket cargo' program". SpaceNews. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022. Retrieved 31 December 2021.

- ^ a b Sauer, Megan (15 December 2021). "Elon Musk: 'I'll be surprised if we're not landing on Mars within five years'". CNBC. Archived from the original on 7 January 2022. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ Vance, Ashlee (2015). Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic Future. HarperCollins. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-0062301239.

- ^ Kooser, Amanda (16 January 2020). "Elon Musk breaks down the Starship numbers for a million-person SpaceX Mars colony". CNET. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- ^ "NASA's management of the Artemis missions" (PDF). NASA Office of Inspector General. 15 November 2021. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2021. Retrieved 22 November 2021.

- ^ Hintze, Paul E.; Meier, Anne J.; Shah, Malay G.; DeVor, Robert. Sabatier System Design Study for a Mars ISRU Propellant Production Plant (PDF). 48th International Conference on Environmental Systems. pp. 1–2, 10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 20 December 2021 – via NASA STI Program.

- ^ Berger, Eric (2 July 2021). "Rocket Report: Super Heavy rolls to launch site, Funk will get to fly". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 6 October 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ a b c "Draft Programmatic Environmental Assessment for the SpaceX Starship/Super Heavy Launch Vehicle Program at the SpaceX Boca Chica Launch Site in Cameron County, Texas" (PDF). FAA. September 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 September 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ "STARGATE – Spacecraft Tracking and Astronomical Research into Gigahertz Astrophysical Transient Emission". University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ Berger, Eric (16 April 2021). "Rocket Report: SpaceX to build huge launch tower, Branson sells Virgin stock". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 11 January 2022.

- ^ Cuthbertson, Anthony (30 August 2021). "SpaceX will use 'robot chopsticks' to catch massive rocket, Elon Musk says". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 September 2021. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

- ^ "ENSCO 8500 Series® Ultra-Deepwater Semisubmersibles" (PDF). Valaris plc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 January 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (17 December 2021). "NASA promotes East Coast Starship option at LC-49 following SpaceX interest". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 6 January 2022.

- ^ Davenport, Justin (16 September 2021). "New Raptor Factory under construction at SpaceX McGregor amid continued engine testing". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (22 February 2022). "Focus on Florida - SpaceX lays the ground work for East Coast Starship sites". NASASpaceFlight.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2022. Retrieved 4 March 2022.