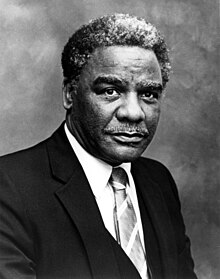

Harold Washington

Harold Washington | |

|---|---|

| |

| 51st Mayor of Chicago | |

| In office April 29, 1983 – November 25, 1987 | |

| Deputy | Richard Mell David Orr |

| Preceded by | Jane Byrne |

| Succeeded by | David Orr (acting) |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois's 1st district | |

| In office January 3, 1981 – April 30, 1983 | |

| Preceded by | Bennett Stewart |

| Succeeded by | Charles A. Hayes |

| Member of the Illinois Senate from the 26th district | |

| In office May 7, 1977 – November 20, 1980 | |

| Preceded by | Cecil A. Partee |

| Succeeded by | James C. Taylor |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the 26th district | |

| In office March 22, 1965 – August 8, 1976 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Harold Lee Washington April 15, 1922 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | November 25, 1987 (aged 65) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oak Woods Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Dorothy Finch

(m. 1942; div. 1950) |

| Domestic partner | Mary Ella Smith (1967–1987) |

| Education | Roosevelt University (BA) Northwestern University (JD) |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1942–1945 |

| Rank | First Sergeant |

| Unit | United States Army Air Corps United States Army Air Forces |

| Battles/wars | World War II • South Pacific • Central Pacific |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Transit projects

|

||

Harold Lee Washington (April 15, 1922 – November 25, 1987) was an American lawyer and politician who was the 51st Mayor of Chicago.[1] Washington became the first African American to be elected as the city's mayor in April 1983. He served as mayor from April 29, 1983, until his death on November 25, 1987. Born in Chicago and raised in the Bronzeville neighborhood, Washington became involved in local 3rd Ward politics under Chicago Alderman and future Congressman Ralph Metcalfe after graduating from Roosevelt University and Northwestern University School of Law.[2][3] Washington was a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1981 to 1983, representing Illinois's first district. Washington had previously served in the Illinois State Senate and the Illinois House of Representatives from 1965 until 1976.

Biography

Ancestry

The earliest known ancestor of Harold Lee Washington, Isam/Isham Washington, was born a slave in 1832 in North Carolina.[4] In 1864, he enlisted in the 8th United States Colored Heavy Artillery, Company L, in Paducah, Kentucky. Following his discharge in 1866, he began farming with his wife Rebecca Neal in Ballard County, Kentucky. Among their six children was Isam/Isom McDaniel (Mack) Washington, who was born in 1875. In 1896, Mack Washington had married Arbella Weeks of Massac County, who had been born in Mississippi in 1878. In 1897, their first son, Roy L. Washington, father of Mayor Washington was born in Ballard County, Kentucky. In 1903, shortly after both families moved to Massac County, Illinois, the elder Washington died. After farming for a time, Mack Washington became a minister in the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church, serving numerous churches in Illinois until the death of his wife in 1952. Reverend I.M.D. Washington died in 1953.[4]

Early life and education

Harold Lee Washington was born on April 15, 1922, at Cook County Hospital in Chicago, Illinois,[5] to Roy and Bertha Washington. While still in high school in Lawrenceville, Illinois, Roy met Bertha from nearby Carrier Mills and the two married in 1916 in Harrisburg, Illinois.[6] Their first son, Roy Jr., was born in Carrier Mills before the family moved to Chicago where Roy enrolled in Kent College of Law. A lawyer, he became one of the first black precinct captains in the city, and a Methodist minister.[7] In 1918, daughter Geneva was born and second son Edward was born in 1920. Bertha left the family, possibly to seek her fortune as a singer, and the couple divorced in 1928. Bertha remarried and had seven more children including Ramon Price, who was an artist and eventually became chief curator of The DuSable Museum of African American History. Harold Washington grew up in Bronzeville, a Chicago neighborhood that was the center of black culture for the entire Midwest in the early and middle 20th century. Edward and Harold stayed with their father while Roy Jr. and Geneva were cared for by grandparents. After attending St Benedict the Moor Boarding School in Milwaukee from 1928 to 1932, Washington attended DuSable High School, then a newly established racially segregated public high school, and was a member of its first graduating class. In a 1939 citywide track meet, Washington placed first in the 110-meter high hurdles event, and second in the 220-meter low hurdles event. Between his junior and senior year of high school, Washington dropped out, claiming that he no longer felt challenged by the coursework. He worked at a meatpacking plant for a time before his father helped him get a job at the U.S. Treasury branch in the city. There he met Nancy Dorothy Finch, whom he married soon after; Washington was 19 years old and Dorothy was 17 years old. Seven months later, the U.S. was drawn into World War II with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on Sunday, December 7, 1941.

Military service

In 1942, Washington was drafted into the United States Army for the war effort and after basic training, sent overseas as part of a racially segregated unit of the U.S. Army Air Corps unit of Engineers. After the American invasion of the Philippines in 1944, on Leyte Island and later the main Luzon island, Washington was part of a unit building runways for bombers, protective fighter aircraft, refueling planes, and returning damaged aircraft. Eventually, Washington rose to the rank of First Sergeant in the Army Air Forces.

Roosevelt College

In the summer of 1946, Washington, aged 24 and a war veteran, enrolled at Roosevelt College (now Roosevelt University).[8] Washington joined other groups of students not permitted to enroll in other local colleges. Local estimates placed the student population of Roosevelt College at about 1/8 black and 1/2 Jewish. A full 75% of the students had enrolled because of the "nondiscriminatory progressive principles."[8] He chaired a fund-raising drive by students, and then was named to a committee that supported citywide efforts to outlaw "restrictive covenants" in housing, the legal means by which ethnic minorities (especially blacks and, to a lesser extent, Jews) were prohibited from purchasing real estate in predominantly white neighborhoods of the city.[9]

In 1946, after the college had moved to the Auditorium Building, Washington was elected the third president of Roosevelt's student council. Under his leadership, the student council successfully petitioned the college to have student representation on Roosevelt's faculty committees. At the first regional meeting of the newly founded National Student Association in the spring of 1948, Washington and nine other delegates proposed student representation on college faculties, and a "Bill of Rights" for students; both measures were roundly defeated.[10] The next year, Washington went to the state capital at Springfield to protest Illinois legislators' coming probe of "subversives". The probe of investigation would outlaw the Communist Party and require "loyalty oaths" for teachers. He led students' opposition to the bills, although they would pass later in 1949.[10]

During his Roosevelt College years, Washington came to be known for his stability. His friends said that he had a "remarkable ability to keep cool", reason carefully and walk a middle line. Washington intentionally avoided extremist activities, including street actions and sit-ins against racially segregated restaurants and businesses. Overall, Washington and other radical activists ended up sharing a mutual respect for each other, acknowledging both Washington's pragmatism and the activists' idealism. With the opportunities found only at Roosevelt College in the late 1940s, Washington's time at the Roosevelt College proved to be pivotal.[11] Washington graduated in August 1949, with a Bachelor of Arts (B.A.) degree. In addition to his activities at Roosevelt, he was a member of Phi Beta Sigma fraternity.[12][13]

Northwestern University School of Law

Washington then applied for and was admitted to study law at the Northwestern University School of Law in Chicago. During this time, Washington was divorced from Dorothy Finch. By some accounts, Harold and Dorothy had simply grown apart after Washington was sent overseas during the war during the first year of his marriage. Others saw both as young and headstrong, the relationship doomed from the beginning. Another friend of Washington's deemed Harold "not the marrying kind." He would not marry again, but continued to have relationships with other women; his longtime secretary is said to have said, "If every woman Harold slept with stood at one end of City Hall, the building would sink five inches into LaSalle Street!".[14]

At Northwestern Law School, Washington was the only black student in his class (there were six women in the class, one of them being Dawn Clark Netsch). As at Roosevelt, he entered school politics. In 1951, his last year, he was elected treasurer of the Junior Bar Association (JBA). The election was largely symbolic, however, and Washington's attempts to give the JBA more authority at Northwestern were largely unsuccessful.[15] On campus, Washington joined the Nu Beta Epsilon fraternity, largely because he and the other people who were members of ethnic minority groups which constituted the fraternity were blatantly excluded from the other fraternities on campus. Overall, Washington stayed away from the activism that defined his years at Roosevelt. During the evenings and weekends, he worked to supplement his GI Bill income. He received his JD in 1952.[16]

Early political career

From 1951 until he was first slated for election in 1965, Washington worked in the offices of the 3rd Ward Alderman, former Olympic athlete Ralph Metcalfe. Richard J. Daley was elected party chairman in 1952. Daley replaced C.C. Wimbush, an ally of William Dawson, on the party committee with Metcalfe. Under Metcalfe, the 3rd Ward was a critical factor in Mayor Daley's 1955 mayoral election victory and ranked first in the city in the size of its Democratic plurality in 1961.[17] While working under Metcalfe, Washington began to organize the 3rd Ward's Young Democrats (YD) organization. At YD conventions, the 3rd Ward would push for numerous resolutions in the interest of blacks. Eventually, other black YD organizations would come to the 3rd Ward headquarters for advice on how to run their own organizations. Like he had at Roosevelt College, Washington avoided radicalism and preferred to work through the party to engender change.[18]

While working with the Young Democrats, Washington met Mary Ella Smith.[19] They dated for the next 20 years, and in 1983 Washington proposed to Smith. In an interview with the Chicago Sun-Times, Smith said that she never pressed Washington for marriage because she knew Washington's first love was politics, saying, "He was a political animal. He thrived on it, and I knew any thoughts of marriage would have to wait. I wasn't concerned about that. I just knew the day would come."[20]

In 1959 Al Janney, Gus Savage, Lemuel Bentley, Bennett Johnson, Luster Jackson and others founded the Chicago League of Negro Voters, one of the first African-American political organizations in the city. In its first election, Bentley drew 60,000 votes for city clerk. The endorsement of the League was deciding factor in the re-election of Leon DesPres who was an independent voice in the City Council. Washington was a close friend of the founders of the League and worked with them from time to time. The League was key in electing Anna Langford, William Cousins and A. A. "Sammy" Rayner who were not part of the Daley machine. In 1963 the group moved to racially integrate and formed Protest at the Polls at a citywide conference which Washington independent candidates had gained traction within the black community, winning several aldermanic seats. In 1983, Protest at the Polls was instrumental in Washington's run for mayor. By then, the YDs were losing to independent candidates.[21]

Legislative career

Illinois House (1965–1976)

After the state legislature failed to reapportion districts every ten years as required by the census, the 1964 Illinois House of Representatives election was held at-large to elect all 177 members of the Illinois House of Representatives. With the Republicans and Democrats each only running 118 candidates, independent voting groups attempted to slate candidates. The League of Negro Voters created a "Third Slate" of 59 candidates, announcing the creation of the slate on June 27, 1964. Shortly afterwards, Daley created a slate which included Adlai Stevenson III and Washington. The Third Slate was then thrown out by the Illinois Election Board because of "insufficient signatures" on the nominating petitions. In the election, Washington was elected as part of the winning Democratic slate of candidates.[22] Washington's years in the Illinois House were marked by tension with Democratic Party leadership. In 1967, he was ranked by the Independent Voters of Illinois (IVI) as the fourth-most independent legislator in the Illinois House and named Best Legislator of the Year. His defiance of the "idiot card", a sheet of paper that directed legislators' votes on every issue, attracted the attention of party leaders, who moved to remove Washington from his legislative position.[23] Daley often told Metcalfe to dump Washington as a candidate, but Metcalfe did not want to risk losing the 3rd Ward's Young Democrats, who were mostly aligned with Washington.[24]

Washington backed Renault Robinson, a black police officer and one of the founders of the Afro-American Patrolmen's League (AAPL). The aim of the AAPL was to fight against the racism which was directed against minority officers by the rest of the predominantly white department. Soon after the creation of the group, Robinson was written up for minor infractions, suspended, reinstated, and then placed on the graveyard shift on a single block behind central police headquarters. Robinson approached Washington and asked him to fashion a bill which would authorize the creation of a civilian review board, consisting of both patrolmen and officers, to monitor police brutality. Both black independent and white liberal legislators refused to back the bill, afraid to challenge Daley's grip on the police force.[24]

After Washington announced that he would support the AAPL, Metcalfe refused to protect him from Daley. Washington believed that he had the support of Ralph Tyler Smith, Speaker of the House. Instead, Smith criticized Washington and then allayed Daley's anger. In exchange for the party's backing, Washington would serve on the Chicago Crime Commission, the group Daley tasked with investigating the AAPL's charges. The commission promptly found the AAPL's charges "unwarranted". An angry and humiliated Washington admitted that on the commission, he felt like Daley's "showcase ni***r".[24] In 1969, Daley removed Washington's name from the slate; only by the intervention of Cecil Partee, a party loyalist, was Washington reinstated. The Democratic Party supported Jim Taylor, a former professional boxer, Streets and Sanitation worker, over Washington. With Partee and his own ward's support, Washington defeated Taylor.[23] His years in the House of Representatives were focused on becoming an advocate for black rights. He continued work on the Fair Housing Act, and worked to strengthen the state's Fair Employment Practices Commission (FEPC). In addition, he worked on a state Civil Rights Act, which would strengthen employment and housing provisions in the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964. In his first session, all of his bills were sent to committee or tabled. Like his time in Roosevelt College, Washington relied on parliamentary tactics (e.g., writing amendments guaranteed to fail in a vote) to enable him to bargain for more concessions.[25]

Washington was accused of failing to file a tax return, even though the tax was paid. He was found guilty and sentenced to 36 days in jail. (1971)[26][27]

Washington also passed bills in honor of civil rights figures. He passed a resolution in honor of Metcalfe, his mentor. He also passed a resolution in honor of James J. Reeb, a Unitarian minister who was beaten to death by a segregationist mob in Selma, Alabama. After the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., he introduced a series of bills which were aimed at making King's birthday a state holiday.[28] The first was tabled and later vetoed. The third bill he introduced, which was passed and signed by Gov. Richard Ogilvie, made Dr. King's birthday a commemorative day observed by Illinois public schools.[29] It was not until 1973 that Washington was able, with Partee's help in the Senate, to have the bill enacted and signed by the governor.[30]

1975 speakership campaign

Washington ran a largely symbolic campaign for Speaker. He only received votes from himself and from Lewis A. H. Caldwell.[31] However, with a divided Democratic caucus, this was enough to help deny Daley-backed Clyde Choate the nomination, helping to throw it to William A. Redmond after 92 rounds of voting.[31]

Redmond had Washington appointed as chairman of the Judiciary Committee.[31]

Legal issues

In addition to Daley's strong-arm tactics, Washington's time in the Illinois House was also marred by problems with tax returns and allegations of not performing services owed to his clients. In her biography, Levinsohn questions whether the timing of Washington's legal troubles was politically motivated. In November 1966, Washington was re-elected to the House over Daley's strong objections; the first complaint was filed in 1964; the second was filed by January 1967.[32] A letter asking Washington to explain the matter was sent on January 5, 1967. After failing to respond to numerous summons and subpoenas, the commission recommend a five-year suspension on March 18, 1968. A formal response to the charges did not occur until July 10, 1969. In his reply, Washington said that "sometimes personal problems are enlarged out of proportion to the entire life picture at the time and the more important things are abandoned." In 1970, the Board of Managers of the Chicago Bar Association ruled that Washington's license be suspended for only one year, not the five recommended; the total amount in question between all six clients was $205.[33]

In 1971, Washington was charged with failure to file tax returns for four years, although the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) claimed to have evidence for nineteen years. Judge Sam Perry noted that he was "disturbed that this case ever made it to my courtroom" — while Washington had paid his taxes, he ended up owing the government a total of $508 as a result of not filing his returns. Typically, the IRS handled such cases in civil court, or within its bureaucracy. Washington pleaded "no contest" and was sentenced to forty days in Cook County Jail, a $1,000 fine, and three years of probation.[34][35]

Illinois Senate (1976–1980)

Campaign for a seat on the Illinois Senate

In 1975, Partee, now President of the Senate and eligible for his pension, decided to retire from the Senate. Although Daley and Taylor declined at first, at Partee's insistence, Washington was ultimately slated for the seat and he received the party's support.[36] Daley had been displeased with Washington for having run a symbolic challenge in 1975 to Daley-backed Clyde Choate for Illinois Speaker of the House (Washington had only received two votes).[36] Additionally, he had ultimately helped push the vote towards Redmond as a compromise candidate.[31] The United Automobile Workers union, whose backing Washington obtained, were critical in persuading Daley to relent to back his candidacy.[31]

Washington defeated Anna Langford by nearly 2,000 votes in the Democratic primary.[31] He went on to win the general election.

Human Rights Act of 1980

In the Illinois Senate, Washington's main focus worked to pass 1980's Illinois Human Rights Act. Legislators rewrote all of the human rights laws in the state, restricting discrimination based on "race, color, religion, sex, national origin, ancestry, age, marital status, physical or mental disability, military status, sexual orientation, or unfavorable discharge from military service in connection with employment, real estate transactions, access to financial credit, and the availability of public accommodations."[37] The bill's origins began in 1970 with the rewriting of the Illinois Constitution. The new constitution required all governmental agencies and departments to be reorganized for efficiency. Republican governor James R. Thompson reorganized low-profile departments before his re-election in 1978. In 1979, during the early stages of his second term and immediately in the aftermath of the largest vote for a gubernatorial candidate in the state's history, Thompson called for human rights reorganization.[38] The bill would consolidate and remove some agencies, eliminating a number of political jobs. Some Democratic legislators would oppose any measure backed by Washington, Thompson and Republican legislators.

For many years, human rights had been a campaign issue brought up and backed by Democrats. Thompson's staffers brought the bill to Washington and other black legislators before it was presented to the legislature. Washington made adjustments in anticipation of some legislators' concerns regarding the bill, before speaking for it in April 1979. On May 24, 1979, the bill passed the Senate by a vote of 59 to 1, with two voting present and six absent. The victory in the Senate was attributed by a Thompson staffer to Washington's "calm noncombative presentation".[39] However, the bill stalled in the House. State Representative Susan Catania insisted on attaching an amendment to allow women guarantees in the use of credit cards. This effort was assisted by Carol Moseley Braun, a representative from Hyde Park who would later go on to serve as a U.S. Senator. State Representatives Jim Taylor and Larry Bullock introduced over one hundred amendments, including the text of the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution, to try to stall the bill. With Catania's amendment, the bill passed the House, but the Senate refused to accept the amendment. On June 30, 1979, the legislature adjourned.[39]

U.S. House (1981–1983)

In 1980, Washington was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in Illinois's 1st congressional district. He defeated incumbent Representative Bennett Stewart in the Democratic primary.[12][40] Anticipating that the Democratic Party would challenge him in his bid for re-nomination in 1982, Washington spent much of his first term campaigning for re-election, often travelling back to Chicago to campaign. Washington missed many House votes, an issue that would come up in his campaign for mayor in 1983.[41] Washington's major congressional accomplishment involved legislation to extend the Voting Rights Act, legislation that opponents had argued was only necessary in an emergency. Others, including Congressman Henry Hyde, had submitted amendments designed to seriously weaken the power of the Voting Rights Act.

Although he had been called "crazy" for railing in the House of Representatives against deep cuts to social programs, Associated Press political reporter Mike Robinson noted that Washington worked "quietly and thoughtfully" as the time came to pass the act. During hearings in the South regarding the Voting Rights Act, Washington asked questions that shed light on tactics used to prevent African Americans from voting (among them, closing registration early, literacy tests, and gerrymandering). After the amendments were submitted on the floor, Washington spoke from prepared speeches that avoided rhetoric and addressed the issues. As a result, the amendments were defeated, and Congress passed the Voting Rights Act Extension.[42] By the time Washington faced re-election in 1982, he had cemented his popularity in the 1st Congressional District. Jane Byrne could not find one serious candidate to run against Washington for his re-election campaign. He had collected 250,000 signatures to get on the ballot, although only 610 signatures (0.5% of the voters in the previous election) were required. With his re-election to Congress locked up, Washington turned his attention to the next Chicago mayoral election.[43]

Mayor of Chicago (1983–1987)

1983 Chicago mayoral election

In the February 22, 1983, Democratic mayoral primary, more than 100,000 new voters registered to vote led by a coalition that included the Latino reformed gang Young Lords led by Jose Cha Cha Jimenez. On the North and Northwest Sides, the incumbent mayor Jane Byrne led and future mayor Richard M. Daley, son of the late Mayor Richard J. Daley, finished a close second. Harold Washington had massive majorities on the South and West Sides. Southwest Side voters overwhelmingly supported Daley. Washington won with 37% of the vote, versus 33% for Byrne and 30% for Daley. Although winning the Democratic primary was normally considered tantamount to election in heavily Democratic Chicago, after his primary victory Washington found that his Republican opponent, former state legislator Bernard Epton (earlier considered a nominal stand-in), was supported by many high-ranking Democrats and their ward organizations, including the chairman of the Cook County Democratic Party, Alderman Edward Vrdolyak.[44]

Epton's campaign referred to, among other things, Washington's conviction for failure to file income tax returns (he had paid the taxes, but had not filed a return). Washington, on the other hand, stressed reforming the Chicago patronage system and the need for a jobs program in a tight economy. In the April 12, 1983, mayoral general election, Washington defeated Epton by 3.7%, 51.7% to 48.0%, to become mayor of Chicago.[45] Washington was sworn in as mayor on April 29, 1983, and resigned his Congressional seat the following day.

First term and Council Wars

During his tenure as mayor, Washington lived at the Hampton House apartments in the Hyde Park neighborhood of Chicago. He created the city's first environmental-affairs department under the management of longtime Great Lakes environmentalist Lee Botts. Washington's first term in office was characterized by conflict with the city council dubbed "Council Wars", referring to the then-recent Star Wars films and caused Chicago to be nicknamed "Beirut on the Lake". A 29-alderman City Council majority refused to enact Washington's legislation and prevented him from appointing nominees to boards and commissions. First-term challenges included city population loss and a massive decrease in ridership on the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA).[citation needed] Assertions that the overall crime rate increased were incorrect.[46]

The 29, also known as the "Vrdolyak 29", were led by Vrdolyak (who was an Alderman in addition to Cook County Democratic Party chairman) and Finance Chair, Alderman Edward Burke. Parks superintendent Edmund Kelly also opposed the mayor. The three were known as "the Eddies" and were supported by the younger Daley (now State's Attorney), U.S. Congressmen Dan Rostenkowski and William Lipinski, and much of the Democratic Party. During his first city council meeting, Washington and the 21 supportive aldermen walked out of the meeting after a quorum had been established. Vrdolyak and the other 28 then chose committee chairmen and assigned aldermen to the various committees. Later lawsuits submitted by Washington and others were dismissed by Supreme Court Justice James C. Murray[47] because it was determined that the appointments were legally made. Washington ruled by veto. The 29 lacked the 30th vote they needed to override Washington's veto; female and African American aldermen supported Washington despite pressure from the Eddies. Meanwhile, in the courts, Washington kept the pressure on to reverse the redistricting of city council wards that the city council had created during the Byrne years. During special elections in 1986, victorious Washington-backed candidates in the first round ensured at least 24 supporters in the city council. Six weeks later, when Marlene Carter and Luís Gutiérrez won run-off elections, Washington had the 25 aldermen he needed. His vote as president of the City Council enabled him to break 25–25 tie-votes and enact his programs.

1987 election

Washington defeated former mayor Jane Byrne in the February 24, 1987, Democratic mayoral primary by 7.2%, 53.5% to 46.3%, and in the April 7, 1987, mayoral general election defeated Vrdolyak (Illinois Solidarity Party) by 11.8%, 53.8% to 42.8%, with Northwestern University business professor Donald Haider (Republican) getting 4.3%, to win reelection to a second term as mayor. Cook County Assessor Thomas Hynes (Chicago First Party), a Daley ally, dropped out of the race 36 hours before the mayoral general election. During Washington's short second term, the Eddies lost much of their power: Vrdolyak became a Republican, Kelly was removed from his powerful parks post, and Burke lost his Finance Committee chairmanship.

Political Education Project (PEP)

From March 1984 to 1987, the Political Education Project (PEP)[48] served as Washington's political arm, organizing both Washington's campaigns and the campaigns of his political allies. Harold Washington established the Political Education Project in 1984. This organization supported Washington's interests in electoral politics beyond the Office of the Mayor.[49][50] PEP helped organize political candidates for statewide elections in 1984 and managed Washington's participation in the 1984 Democratic National Convention as a "favorite son" presidential candidate.[51] PEP used its political connections to support candidates such as Luis Gutiérrez and Jesús "Chuy" García through field operations, voter registration and Election Day poll monitoring. Once elected, these aldermen helped break the stalemate between Washington and his opponents in the city council. Due to PEP's efforts, Washington's City Council legislation gained ground and his popularity grew as the 1987 mayoral election approached.[52] In preparation for the 1987 mayoral election, PEP formed the Committee to Re-Elect Mayor Washington. This organization carried out fundraising for the campaign, conducted campaign events, and coordinated volunteers.[53] PEP staff members, such as Joseph Gardner and Helen Shiller, went on to play leading roles in Chicago politics.[54]

The organization disbanded upon Harold Washington's death.[55] Harold Washington's Political Education Project Records is an archival collection detailing the organization's work. It is located in the Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Harold Washington Library Center, Chicago, Illinois.[56]

DuSable Park

Washington, during his mayorship, announced a plan to redevelop a commercial site into a DuSable Park, named in honor of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, the honorary founder of the city. The project has yet to be completed, has experienced a number of bureaucratic reconceptions and roadblocks, and is currently spearheaded by the DuSable Heritage Association.

Approval ratings

Despite tumult between Washington and the City Council, Washington enjoyed positive approval among the city's residents.[57]

An April 1987 Chicago Tribune poll of voters indicated that there was a significant age and gender gap in Washington's approval, with Washington being more popularly approved of by voters under the age of 55 and by male voters.[58]

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Segment polled | Polling source | Date | Approve | Disapprove | Sample size | Margin-of-error | Polling method | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered voters | Market Shares Corp. and Chicago Tribune | March 12–15, 1987 | 67% | 1,145 | ±3 | Telephone | [59] | |

| Registered voters | Penn Schoen | October 1986 | 54% | 39% | 1,200 | [60] | ||

| Residents | Chicago Tribune | October 29–November 3, 1985 | 60% | 30% | 515 | [61] | ||

| Residents | Chicago Tribune | March 1985 | 35% | 21% | [61] | |||

| Chicago Tribune | 1985 | 54% | 36% | [57] |

Historical assessments

A 1993 survey of historians, political scientists and urban experts conducted by Melvin G. Holli of the University of Illinois at Chicago ranked Washington as the nineteenth-best American big-city mayor to have served between the years 1820 and 1993.[62]

Death and funeral

On November 25, 1987, at 11:00 am, Chicago Fire Department paramedics were called to City Hall. Washington's press secretary, Alton Miller, had been discussing school board issues with the mayor when Washington suddenly slumped over on his desk, falling unconscious. After failing to revive Washington in his office, paramedics rushed him to Northwestern Memorial Hospital. Further attempts to revive him failed, and Washington was pronounced dead at 1:36 p.m.[63] At Daley Plaza, Patrick Keen, project director for the Westside Habitat for Humanity, announced Washington's official time of death to a separate gathering of Chicagoans. Initial reactions to the pronouncement of his death were of shock and sadness, as many black people believed that Washington was the only top Chicago official who would address their concerns.[64][65] Thousands of Chicagoans attended his wake in the lobby of City Hall between November 27 and 29, 1987.[66] On November 30, 1987, Reverend B. Herbert Martin officiated Washington's funeral service in Christ Universal Temple at 119th Street and Ashland Avenue in Chicago. After the service, Washington was buried in Oak Woods Cemetery on the South Side of Chicago.[67][68]

Rumors

Immediately after Washington's death, rumors about how Washington died began to surface. On January 6, 1988, Dr. Antonio Senat, Washington's personal physician, denied "unfounded speculations" that Washington had cocaine in his system at the time of his death, or that foul play was involved. Cook County Medical Examiner Robert J. Stein performed an autopsy on Washington and concluded that Washington had died of a heart attack. Washington had weighed 284 pounds (129 kg), and suffered from hypertension, high cholesterol levels, and an enlarged heart.[69] On June 20, 1988, Alton Miller again indicated that drug reports on Washington had come back negative, and that Washington had not been poisoned prior to his death. Dr. Stein stated that the only drug in Washington's system had been lidocaine, which is used to stabilize the heart after a heart attack takes place. The drug was given to Washington either by paramedics or by doctors at Northwestern Memorial Hospital.[70] Bernard Epton, Washington's opponent in the 1983 general election, died 18 days later, on December 13, 1987.

Legacy

At a party held shortly after his re-election on April 7, 1987, Washington said to a group of supporters, "In the old days, when you told people in other countries that you were from Chicago, they would say, 'Boom-boom! Rat-a-tat-tat!' Nowadays, they say [crowd joins with him], 'How's Harold?'!"[71]

In later years, various city facilities and institutions were named or renamed after the late mayor to commemorate his legacy. The new building housing the main branch of the Chicago Public Library, located at 400 South State Street, was named the Harold Washington Library Center. The Chicago Public Library Special Collections, located on the building's 9th floor, house the Harold Washington Archives and Collections. These archives hold numerous collections related to Washington's life and political career.[72]

Five months after Washington's sudden death in office, a ceremony was held on April 19, 1988, changing the name of Loop College, one of the City Colleges of Chicago, to Harold Washington College. Harold Washington Elementary School in Chicago's Chatham neighborhood is also named after the former mayor. In August 2004, the 40,000-square-foot (3,700 m2) Harold Washington Cultural Center opened to the public in the Bronzeville neighborhood. Across from the Hampton House apartments where Washington lived, a city park was renamed Harold Washington Park, which was known for "Harold's Parakeets",[73] a colony of feral monk parakeets that inhabited Ash Trees in the park. A building on the campus of Chicago State University is named Harold Washington Hall.[74]

Six months after Washington's death, School of the Art Institute of Chicago student David Nelson painted Mirth & Girth, a full-length portrait depicting Washington wearing women's lingerie. The work was unveiled on May 11, 1988, opening day of SAIC's annual student exhibition.[75] Within hours, City aldermen and members of the Chicago Police Department seized the painting. It was later returned, but with a five-inch (13 cm) gash in the canvas. Nelson, assisted by the ACLU, filed a federal lawsuit against the city, claiming that the painting's confiscation and subsequent damaging violated his First Amendment rights. The complainants eventually split a US$95,000 (1994, US$138,000 in 2008) settlement from the city.[76]

Electoral history

Illinois State Representative

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Democratic | Leland J. Kennedy (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Paul E. Rink (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | James D. Carrigan (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Joe W. Russell (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Melvin McNairy | |||

| Democratic | Harold Washington | |||

| Democratic | John Jerome (Jack) Hill (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Clyde Lee (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Clyde L. Choate (incumbent) | |||

| Democratic | Charles Ed Schaefer (incumbent) | |||

| . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | |

| Total votes | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 28,426.5 | 57.9 | |

| Democratic | Owen D. Pelt | 17,035.5 | 34.6 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin | 3,818 | 7.8 | |

| Total votes | 49,280 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 55,513 | 44.2 | |

| Democratic | Owen D. Pelt | 53,783.5 | 42.8 | |

| Republican | J. Horace Gardner | 16,294.5 | 100 | |

| Total votes | 125,591 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 17,670.5 | 51.6 | |

| Democratic | Owen D. Pelt (incumbent) | 12,153 | 35.5 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin | 2,367 | 6.9 | |

| Democratic | Ulmer D. Lynch, Jr. | 2,067 | 6.0 | |

| Total votes | 34,257.5 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 70,203.5 | 48.3 | |

| Democratic | James C. Taylor | 65,616 | 45.1 | |

| Republican | J. Horace Gardner (incumbent) | 9,571.5 | 6.6 | |

| Total votes | 145,391 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 21,072.5 | 53.4 | |

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 14,828.5 | 37.6 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin | 1,916.5 | 4.9 | |

| Democratic | Clyde Exson | 1,654.5 | 4.2 | |

| Total votes | 39,472 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 45,686 | 48.0 | |

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 42,996 | 45.2 | |

| Republican | J. Horace Gardner (incumbent) | 6,461.5 | 6.7 | |

| Total votes | 95,143.5 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 26,123 | 40.1 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin | 21,199 | 32.5 | |

| Democratic | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 17,876.5 | 27.4 | |

| Total votes | 65,198.5 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 49,706.5 | 37.2 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin | 47,527.5 | 35.6 | |

| Independent | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 25,240 | 18.9 | |

| Republican | Maurice Beacham | 11,042 | 8.3 | |

| Total votes | 133,516 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 27,999 | 54.0 | |

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 12,854.5 | 24.8 | |

| Democratic | Peggy Smith Martin (incumbent) | 10,960 | 21.2 | |

| Total votes | 51,813.5 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 30,556.5 | 41.4 | |

| Democratic | James C. Taylor (incumbent) | 29,764.5 | 40.3 | |

| Independent | Taylor Pouncey | 8,685.5 | 11.8 | |

| Republican | Jerry Washington, Jr. | 2,990.5 | 4.1 | |

| Republican | Magnolia Prowell | 1,817 | 2.5 | |

| Total votes | 73,814 | 100 | ||

Illinois State Senator

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 9,030 | 56.7 | |

| Democratic | Anna R. Langford | 6,897 | 43.3 | |

| Total votes | 15,927 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 42,365 | 95.2 | |

| Republican | Edward F. Brown | 2,147 | 4.8 | |

| Total votes | 44,512 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 8,953 | 49.3 | |

| Democratic | Clarence C. Barry | 8,734 | 48.1 | |

| Democratic | Sabrina A. Washington | 459 | 2.5 | |

| Total votes | 18,146 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 21,291 | 81.4 | |

| Citizens For Taylor Pouncey | Clarence C. Barry | 4,854 | 18.6 | |

| Total votes | 26,145 | 100 | ||

U.S. Congressman

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 30,522 | 47.7 | |

| Democratic | Ralph H. Metcalfe, Jr. | 12,356 | 19.3 | |

| Democratic | Bennett M. Stewart (incumbent) | 10,810 | 16.9 | |

| Democratic | John H. Stroger, Jr. | 10,284 | 16.1 | |

| Write-in | 11 | nil | ||

| Total votes | 63,983 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 119,562 | 95.5 | |

| Republican | George Williams | 5,660 | 4.5 | |

| Write-in | 1 | nil | ||

| Total votes | 125,223 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 69,799 | 100 | |

| Write-in | 8 | nil | ||

| Total votes | 69,807 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 172,641 | 97.3 | |

| Republican | Charles Allen Taliaferro | 4,820 | 2.7 | |

| Write-in | 1 | nil | ||

| Total votes | 177,462 | 100 | ||

Chicago Mayor

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Michael A. Bilandic (incumbent) | 368,404 | 51.1 | |

| Democratic | Roman Pucinski | 235,795 | 32.7 | |

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 77,322 | 10.7 | |

| Democratic | Edward Hanrahan | 28,643 | 4.0 | |

| Democratic | Anthony Robert Martin-Trignona | 6,674 | 0.9 | |

| Democratic | Ellis Reid | 4,022 | 0.6 | |

| Total votes | 720,860 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 424,324 | 36.3 | |

| Democratic | Jane Byrne (incumbent) | 393,500 | 33.6 | |

| Democratic | Richard M. Daley | 346,835 | 29.7 | |

| Democratic | Frank R. Ranallo | 2,367 | 0.2 | |

| Democratic | William Markowski | 1,412 | 0.1 | |

| Democratic | Sheila Jones | 1,285 | 0.1 | |

| Total votes | 1,169,723 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington | 668,176 | 51.7 | |

| Republican | Bernard Epton | 619,926 | 48.0 | |

| Socialist Workers | Eddie L. Warren | 3,756 | 0.3 | |

| Total votes | 1,291,858 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 586,841 | 53.5 | |

| Democratic | Jane Byrne | 507,603 | 46.3 | |

| Democratic | Sheila Jones | 2,549 | 0.2 | |

| Total votes | 1,096,993 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Harold Washington (incumbent) | 600,290 | 53.8 | |

| Illinois Solidarity Party | Edward Vrdolyak | 468,493 | 42.0 | |

| Republican | Donald Haider | 47,652 | 4.3 | |

| Total votes | 1,116,435 | 100 | ||

See also

- List of African-American United States representatives

- Ed Lee, the first Asian American Mayor of San Francisco, who also died in office of a heart attack at the same age as Washington

- Events in the Life of Harold Washington (mural)

Notes

- ^ This is a pulled list of ten candidates with similar vote totals to Harold Washington as the original ballot had 236 candidates.

References

- ^ "Chicago Mayors". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- ^ Black Chicago's First Century: 1833–1900, Volume 1; Volumes 1833–1900, By Christopher Robert Reed. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ Jet, Sep 6, 2004. Retrieved March 9, 2020.

- ^ a b Brasfield, Curtis (1993). The Ancestry of Mayor Harold Washington (First ed.). Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc. p. 7, 14–22. ISBN 1556137508.

- ^ Marsh, Carole (2002). Harold Washington: Political Pioneer. Gallopade International. ISBN 978-0635015044. Retrieved May 26, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Brasfield, Curtis (1993). The Ancestry of Mayor Harold Washington. Bowie, Maryland: Heritage Books, Inc. pp. 22–28. ISBN 1556137508.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn, p. 246, relates that Washington identified himself with his grandfather and father Roy's Methodist background. Rivlin, p. 42, notes that at age 4, Harold and his brother, 6, were sent to a private Benedictine school in Wisconsin. The arrangement lasted one week before they ran away from the school and hitchhiked home. After three more years and thirteen escapes, Roy placed Harold in Chicago city public schools.

- ^ a b Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 42–43.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p. 44.

- ^ a b Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 51–53.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 54–55, 59, 62.

- ^ a b United States Congress (n.d.). "Harold Washington". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p. 63.

- ^ Rivlin (1992), p. 53.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p. 66.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 68–70.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p. 75.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 86–90.

- ^ "Mary Ella Smith Still Keeps The Flame". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Kup (December 27, 1987). "Kup on Sunday". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 15, 2008.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 91–92, 97.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 98–99.

- ^ a b Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 100–106.

- ^ a b c Rivlin (1992), pp. 50–52.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 107–108.

- ^ RON GROSSMAN (November 13, 2017). "Remembering Mayor Harold Washington's death, 30 years ago". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ United States House of Representatives. "Washington, Harold". history.house.gov.

- ^ Travis, "Harold," The Peoples Mayor, 81–82 ).

- ^ Travis, "Harold," The Peoples Mayor, 81–82.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 109–110.

- ^ a b c d e f Hamlish Levinsohn (1983)

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 143–144.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 146–152.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 154–156.

- ^ Rivlin (1992), pp. 178–180.

- ^ a b Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 121–122.

- ^ Illinois General Assembly (1970). "(775 ILCS 5/) Illinois Human Rights Act". Retrieved April 21, 2008.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 132–134.

- ^ Cook County Board of Commissioners (December 4, 2007). "Resolution 08-R-09 (Honoring the life of Harold Washington)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), pp. 166–172.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p.172.

- ^ Hamlish Levinsohn (1983), p.176.

- ^ Davis, Robert (April 12, 1983). "The election of Harold Washington the first black mayor of Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved February 16, 2008.

- ^ "Election Results for 1983 General Election, Mayor, Chicago, IL".

- ^ "Harold". This American Life. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ Sheppard (May 17, 1983). "Rebels Win Court Decision in Chicago Council Dispute". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ "Chicago History – PEP Project" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 24, 2016.

- ^ "Lavelle at Home in Hot Seat". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Cassel, Doug (March 16, 1989). "Is Tim Evans for Real?". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Favorite Son Slate Planned". The New York Times. January 4, 1984. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Harold Washington's Political Education Project Records, Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Series IV. Special Aldermanic Election, boxes 29–35, 123" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Harold Washington's Political Education Project Records, Chicago Public Library Special Collections, Series V. 1987 Mayoral Election, boxes 35–100, 123, 124, 126" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Gardner Loses Fight With Cancer". Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Harold Washington's Political Education Project Records, Chicago Public Library Special Collections" (PDF). Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 29, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Moser, Whet (February 1, 2016). "Rahm Emanuel: The Least Popular Mayor in Modern Chicago History". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ Lentz, Philip (April 21, 1987). "Gender, age gap confront mayor in '87 poll shows". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Davis, Robert (March 24, 1987). "Mayor is cruising in job-rating poll". Chicago Tribune.:

- Davis, Robert (March 24, 1987). "Mayor is cruising in job-rating poll". Chicago Tribune. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- Davis, Robert (March 24, 1987). "Mayor". Chicago Tribune. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Vrdolyak". Chicago Tribune. November 18, 1986. Retrieved November 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Neal, Steve (November 18, 1985). "Mayor's job rating at its highest yet". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 26, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Holli, Melvin G. (1999). The American Mayor. University Park: PSU Press. ISBN 0-271-01876-3.

- ^ Davis, Robert (November 26, 1987). "Mayor's death stuns city – black leader, 65, on verge of a dream". Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ Brotman, Barbara (November 26, 1987). "Chicagoans mourn the loss of their leader". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 26, 2008.

- ^ "WBEZ Radio News; 1987 – excerpts, Mourning a Mayor and Moving On". American Archive of Public Broadcasting. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ "Photos: Chicago Mayor Harold Washington – Chicago Tribune". galleries.apps.chicagotribune.com. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ "Chicago Weeps As Mayor Washington Laid To Rest". Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Times, Dirk Johnson and Special To the New York (December 1987). "Foes Unite in Tribute at Chicago Mayor's Funeral". The New York Times. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Lillian (January 7, 1988). "Washington's doctor debunks foul play talk". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Unknown (June 21, 1988). "No drug link to ex-mayor's death". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- ^ Terry, Don; Pitt, Leon (April 8, 1987). "Mayor proves results worth singing about". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 27, 2007.

- ^ Harold Washington Archives and Collections at Chicago Public Library "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 29, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Monk Parakeet Nests in Harold Washington Park Archived March 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chicago State University". csu.edu. Archived from the original on May 1, 2012.

- ^ Hanania, Ray; Cronin, Barry (May 13, 1988). "Art Institute surrenders – Will bar controversial painting of Washington". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved January 27, 2008.

- ^ Lehmann, Daniel J.; Golab, Art (September 21, 1994). "City settles suit over Washington painting". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s "Downloadable Vote Totals". Illinois State Board of Elections. Retrieved September 20, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Election Results for 1977 Primary Election, Mayor, Chicago, IL". Chicago Democracy Project. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Chicago Mayor – D Primary". Our Campaigns. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "Chicago Mayor". Our Campaigns. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Chicago Mayor – D Primary". Our Campaigns. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ "Chicago Mayor". Our Campaigns. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

Further reading

- Bennett, Larry. "Harold Washington and the black urban regime." Urban Affairs Quarterly 28.3 (1993): 423-440.

- Betancur, John J., and Douglas C. Gills. "Community Development in Chicago: From Harold Washington to Richard M. Daley." The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 594.1 (2004): 92-108.

- Betancur, John J., and Douglas C. Gills. "Coalition Experience in Chicago Under Mayor Harold Washington." in The collaborative city: Opportunities and struggles for Blacks and Latinos in US cities (2000): 59+ online.

- Biles, Roger. Mayor Harold Washington: Champion of Race and Reform in Chicago (U of Illinois Press, 2018). online

- Carl, Jim. "Harold Washington and Chicago's Schools Between Civil Rights and the Decline of the New Deal Consensus, 1955–1987." History of Education Quarterly 41.3 (2001): 311-343.

- Clavel, Pierre, and Wim Wiewel, eds. Neighborhood Mayor: Harold Washington and the Neighborhoods: Progressive City Government in Chicago, 1983–1987 (1991)

- Giloth, Robert, and Kari Moe. "Jobs, equity, and the mayoral administration of Harold Washington in Chicago (1983–87)." Policy Studies Journal 27.1 (1999): 129-146. online[permanent dead link]

- Hamlish Levinsohn, Florence (1983). Harold Washington: A Political Biography. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-0914091417.

- Helgeson, Jeffrey. Crucibles of Black Empowerment: Chicago's Neighborhood Politics from the New Deal to Harold Washington (University of Chicago Press, 2014).

- Keating, Ann Durkin. "In the Shadow of Chicago: Postwar Illinois Historiography" Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society Vol. 111, No. 1-2, (2017), pp. 120-136 online

- Keiser, Richard A. "Explaining African-American Political Empowerment Windy City Politics from 1900 to 1983." Urban Affairs Review (1993) 29#1 pp: 84-116.

- Kleppner, Paul. Chicago Divided: The Making of a Black Mayor (1985).

- Mantler, Gordon K. The Multiracial Promise. Harold Washington's Chicago and the Democratic Struggle in Reagan's America (U of North Carolina Press, 2023)

- Marshall, Jon, and Matthew Connor. "Divided Loyalties: The Chicago Defender and Harold Washington's Campaign for Mayor of Chicago." American Journalism 36.4 (2019): 447–472.

- Peterson, Paul E. "Washington's Election in Chicago: The Other Half of the Story." PS: Political Science & Politics 16.4 (1983): 712-716.

- Preston, Michael B. “The Election of Harold Washington: Black Voting Patterns in the 1983 Chicago Mayoral Race.” PS: Political Science & Politics 16#3 1983, pp. 486–88. online

- Rivlin, Gary (1992). Fire on the Prairie: Chicago's Harold Washington and the Politics of Race. New York: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0805014683.

- Travis, Dempsey J. (1989). "Harold," The Peoples Mayor: the Authorized Biography of Mayor Harold Washington. Chicago: Urban Research Press, Inc. ISBN 0941484084.

- Wilson, Asif. "Curricularizing Social Movements: The Election of Chicago's First Black Mayor as Content, Pedagogy, and Futurities." Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 36.2 (2021): 32-42. online

External links

- "Harold" Program 84 – A This American Life radio story that aired on November 21, 1997. It recounts the political history of Washington's mayoralty. Another program on This American Life is Act 4 "The Other Guy," Program 376: Wrong Side of History. This program recounts the story of Bernie Epton, the opponent in the mayoral race against Harold Washington.

- [ The Harold Washington Commemorative Year]

- Harold Washington Archives and Collections at Chicago Public Library

- "The Legacy of Chicago's Harold Washington", Cheryl Corley, All Things Considered, November 23, 2007. Retrieved November 23, 2007.

- Harold Washington on the Legacy of Richard J. Daley on YouTube, video excerpt from a 1986 documentary special on Richard J. Daley

- Harold Washington's Political Education Project Records, Black Metropolis Research Consortium

- Young Lords in Lincoln Park Neighborhood Collection

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Harold Washington

- African-American mayors in Illinois

- Mayors of Chicago

- 1922 births

- 1987 deaths

- African-American members of the United States House of Representatives

- African-American United States Army personnel

- African-American state legislators in Illinois

- United States Army Air Forces personnel of World War II

- Illinois lawyers

- Democratic Party Illinois state senators

- Democratic Party members of the Illinois House of Representatives

- Roosevelt University alumni

- Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law alumni

- United States Army Air Forces soldiers

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from Illinois

- African-American Methodists

- 20th-century American lawyers

- 20th-century American politicians

- African-American history in Chicago

- African Americans in World War II

- Deaths from cardiovascular disease

- 20th-century African-American lawyers