International student

International students, or foreign students, are students who undertake all or part of their tertiary education in a country other than their own and move to that country for the purpose of studying.

In 2020, there were over 6.36 million international students, up from 5.12 million in 2016. The most popular destinations were the United States (with 957,475 international students), the United Kingdom (550,877 students), and Australia (458,279 students), which together receive 31% of international students.[1]

National definitions

The definitions of "foreign student" and "international student" vary from country to country depending on the educational system of the country.[2]

In the US, international students are "[i]ndividuals studying in the United States on a non-immigrant, temporary visa that allows for academic study at the post- secondary level."[3] Most international students in the US hold an F1 Visa.[4]

In Europe, students from countries who are a part of the European Union can take part in a student exchange program called the Erasmus Programme.[5] The program allows for students from the EU to study in other countries under a government agreement.[6]

Canada defines international students as "non-Canadian students who do not have 'permanent resident' status and have had to obtain the authorization of the Canadian government to enter Canada with the intention of pursuing an education."[7] The study permit identifies the level of study and the length of time the individual may study in Canada. Unless it takes more than six months, international students do not need a study permit if they will finish the course within the period of stay authorized upon entry.[8]

In Australia, an international student "is not an Australian citizen, Australian permanent resident, New Zealand citizen, or a holder of an Australian permanent resident humanitarian visa."[9]

According to the Institute of International Education, an international student in Japan is "[a] student from a foreign economy who is receiving an education at any Japanese university, graduate school, junior college, college of technology, professional training college or university preparatory course and who resides in Japan with a 'college student' visa status."[10]

Destinations of foreign students

Student mobility in the first decade of the 21st century has been transformed by three major external events: the 9/11 terrorists attack, the global financial crisis of 2008, and an increasingly isolationist political order characterized by Brexit in the U.K. and the election of Donald Trump in the U.S.[11] The mobility of international students is influenced by many factors, particularly changes to the visa and immigration policies of destination countries that impact the availability of employment during and after education.[11][12] Political developments are often a major consideration; for example, a survey conducted before the 2020 presidential election in the U.S. indicated that a quarter of prospective international students were more likely to study in the country if Joseph R. Biden was elected president.[13]

Australia has by far the highest ratio of international students per head of population in the world by a significant margin, with international students represented on average 26.7% of the student bodies of Australian universities.[14][15]

The greatest percentage increases of numbers of foreign students have occurred in New Zealand, Korea, the Netherlands, Greece, Spain, Italy, and Ireland.[16]

Traditionally the US and UK have been the most prestigious choices, because of the presence of top 10 rankings Universities such as Harvard, Oxford, MIT, and Cambridge. More recently however they have had to compete with the rapidly growing Asian higher education market, especially China. In the 2020 CWTS Leiden Ranking edition, China surpassed the US with the number of universities including in the ranking for the first time (204 vs.198).[17] China is also home to the two best C9 league universities (Tsinghua and Peking) in the Asia-Pacific and emerging countries with its shared rankings at 16th place in the world by the 2022 Times Higher Education World University Rankings.[18] While US is the leading destination for foreign students, there is increasing competition from several destinations in East Asia such as China, Korea, Japan and Taiwan which are keen to attract foreign students for reputation and demographic reasons.[19]

According to OECD, almost one out of five foreign students is regionally mobile. This segment of regionally mobile students who seek global education at local cost is defined as "glocal" students]. Many "glocal" students consider pursuing transnational or cross-border education which allows them to earn a foreign credential while staying in their home countries.[20] With the increase in tuition cost in leading destinations like the US and the UK along with the higher immigration barriers, many international students are exploring alternative destinations and demanding more "value for money." Recalibrating value for money for international students It is projected that the number of internationally mobile students will reach 6.9 million by 2030, an increase of 51%, or 2.3 million students, from 2015.[21] The affordability of international education is an area of concern not only for international students but also universities and nations interested in attracting them.[22]

As of 2022[update], the top 10 countries for foreign student enrollment according to Institute of International Education:[23][24][25][26]

| Rank | Destination country | Numbers of foreign students | Top sending countries | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 2021 | % change | |||

| 1 | 948,519 | 914,095 | +3.77% | China, India, South Korea | |

| 2 | 633,910 | 601,205 | +5.44% | China, India, Nigeria | |

| 3 | 552,580 | 256,455 | +115.47% | India, China, France | |

| 4 | 400,026 | 370,052 | +8.10% | Morocco, Algeria, China | |

| 5 | 363,859 | 429,382 | −15.26% | China, India, Nepal | |

| 6 | 351,127 | 395,263 | −11.17% | Kazakhstan, China, Uzbekistan | |

| 7 | 324,729 | 319,902 | +1.51% | China, India, Syria | |

| 8 | 221,653 | — | South Korea, Thailand, Pakistan | ||

| 9 | 201,877 | 218,783 | −7.73% | China, Vietnam, Nepal | |

| 10 | 125,470 | 112,010 | +12.02% | China, Romania, Albania | |

As of 2020[update], the top 10 countries for foreign student enrollment according to UNESCO:[29]

| Rank | Destination country | Numbers of foreign students | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2019 | % change | ||

| 1 | 957,475 | — | ||

| 2 | 550,877 | 489,019 | +12.65% | |

| 3 | 458,279 | 509,160 | −9.99% | |

| 4 | 368,717 | 333,233 | +10.65% | |

| 5 | 282,922 | — | ||

| 6 | 323,157 | 279,168 | +15.76% | |

| 7 | 252,444 | 246,378 | +2.46% | |

| 8 | 225,100 | 201,177 | +11.89% | |

| 9 | 222,661 | 202,907 | +9.74% | |

| 10 | 215,975 | 225,339 | −4.16% | |

Asia

China

In 2016, China was the third largest receiver of international students globally, with 442,773 international students.[30] By 2018 this number had grown to 492,185 (10.49% growth from 2017).[31]

The number of international students in China has grown steadily since 2003, with apparently no impact from the rise of terrorism or the 2008 global financial crisis. In contrast to the reported decline of enrollments in the USA[32] and the UK,[33] China's international student market continues to strengthen. China is now the leading destination globally for Anglophone African students.[34]

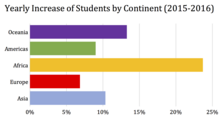

In 2016, the students coming to China were mostly from Asia (60%), followed by Europe (16%) and Africa (14%). However, Africa had the highest growth rate at 23.7% year-on-year 2015–2016.[35]

The top 15 countries sending students to China in 2018 are listed below. African countries are grouped together and show a considerable block of students.[35][36][31]

| Rank (2018) |

Country | Number of Foreign Students | Rank (2017) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2017 | Per cent of Total (2018) | |||

| - | All African countries grouped together |

81,562 | 61,594 | 16.57% | - |

| 1 | 50,600 | 70,540 | 10.28% | 1 | |

| 2 | 28,608 | 23,044 | 5.81% | 2 | |

| 3 | 28,023 | 18,626 | 5.69% | 3 | |

| 4 | 23,192 | 18,717 | 4.71% | 5 | |

| 5 | 20,996 | 23,838 | 4.27% | 4 | |

| 6 | 19,239 | 17,971 | 3.91% | 6 | |

| 7 | 15,050 | 14,714 | 3.06% | 8 | |

| 8 | 14,645 | - | 2.98% | - | |

| 9 | 14,230 | 13,595 | 2.89% | 7 | |

| 10 | 11,784 | 13,996 | 2.39% | 9 | |

| 11 | 11,299 | 10,639 | 2.30% | ||

| 12 | 10,735 | - | 2.18% | - | |

| 13 | 10,695 | - | 2.17% | - | |

| 14 | 10,158 | - | 2.06% | - | |

| 15 | 9,479 | - | 1.93% | - | |

In 2016, international students mostly went to study in the major centers of Beijing (77,234, 17.44%) and Shanghai (59,887, 13.53%). In recent years there has been a decentralization and dispersion of students to other provinces.

Various factors combine to make China a desirable destination for international students.

- China boasts a significant number of world-class universities.[37]

- Universities in China are attractive research centers.[38]

- It costs relatively less than studying in developed countries.[39]

- There is a huge diversity of universities and programs.[39]

- There are more career opportunities due to China's growing economic strength.[39]

- Many graduate and postgraduate programs are offered in English.

- A huge number of scholarships (49,022 in 2016) are on offer from the Chinese government.[35]

China is openly pursuing a policy of growing its soft power globally, by way of persuasion and attraction. Attracting international students, especially by way of scholarships, is one effective way of growing this influence.[40][41]

India

India is an emerging destination for international students. India hosted 49,348 students from 168 countries during the 2019-20 academic year, with the top 10 countries accounting for 63.9% of all international students.[42]

In 2019, India was hosting over 47,000 overseas students and aims to quadruple the number 200,000 students by 2023. India has most its international students and targets from South, Southeast, West Asia and Africa and is running various fee waiver and scholarship programs.[43][44]

| Rank | Country | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13,880 | 28.1% | |

| 2 | 4,504 | 9.1% | |

| 3 | 2,259 | 4.6% | |

| 4 | 1,851 | 3.8% | |

| 5 | 1,758 | 3.6% | |

| 6 | 1,627 | 3.3% | |

| 7 | 1,525 | 3.1% | |

| 8 | 1,437 | 2.9% | |

| 9 | 1,353 | 2.7% | |

| 10 | 1,347 | 2.7% | |

| Share of top 10 countries | 31,533 | 63.9% | |

| Others | 17,815 | 36.1% | |

| Total | 49,348 | 100% | |

Iran

Iran had 55000 studying in 2018 .[45] In 2021 it doubled to more than 130000 with half of them enrolled in Azad University and Payamnoor.[46] Iran Signed up PMF Iraqi Popular Mobilization Forces to study at University of Tehran.[47] By 2023 there were students from 15 countries such as Lebanon, Iraq, Russia, Syria, Pakistan, African countries. They study humanities sciences, law, medicine, construction, accounting.[48][49]

Japan

Japan is perceived as an evolving destination for international students. Japan has around 180,000 overseas students studying at its institutions and the government has set targets to increase this to 300,000 over the next few years.[50] According to the Japan Student Services Organization (JASSO), the number of international students on 1 May 2022 was 231,146 people.[51][52][53]

Malaysia and Singapore

Malaysia, Singapore and India are emerging destinations for international students. These three countries have combined share of approximately 12% of the global student market with somewhere between 250,000 and 300,000 students having decided to pursue higher education studies in these countries in 2005–2006.[54]

The flow of international students above indicates the south-north phenomenon. In this sense, students from Asia prefer to pursue their study, particularly in the United States.

The recent statistics on mobility of international students can be found in;

- The 2009 Global Education Digest (GED)[55] by UNESCO

- International Flows of Mobile Students at the Tertiary Level[56] by UNESCO

- Empowering People to Innovate - International Mobility[57] by OECD.

Australia and Oceania

Australia has the highest ratio of international students per head of population in the world by a large margin, with 775,475 international students enrolled in the nation's universities and vocational institutions in 2020.[58][15] Accordingly, in 2019, international students represented on average 26.7% of the student bodies of Australian universities. International education, therefore, represents one of the country's largest exports and has a pronounced influence on the country's demographics, with a significant proportion of international students remaining in Australia after graduation on various skill and employment visas.[59]

Top 20 countries and regions sending students to Australia in 2023 are listed below.[60]

| Rank | Country | Number of

Students |

Per cent of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 152,395 | 21% | |

| 2 | 118,869 | 17% | |

| 3 | 59,147 | 8% | |

| 4 | 33,494 | 5% | |

| 5 | 29,916 | 4% | |

| 6 | 27,764 | 4% | |

| 7 | 24,241 | 3% | |

| 8 | 22,054 | 3% | |

| 9 | 21,260 | 3% | |

| 10 | 19,166 | 3% | |

| 11 | 15,707 | 2% | |

| 12 | 14,968 | 2% | |

| 13 | 13,207 | 2% | |

| 14 | 12,278 | 4% | |

| 15 | 10,537 | 1% | |

| 16 | 9,640 | 1% | |

| 17 | 9,624 | 1% | |

| 18 | 8,728 | 1% | |

| 19 | 6,866 | 1% | |

| 20 | 6,402 | ||

| Total | 616,263 | 86% | |

| (Total out of 710,893 students in Australia during January to July in 2023) | |||

Europe

France and Germany

In 2016, France was the fourth largest receiver of international students globally, with 245,349 international students, In just a matter of three years, from 2017 to 2020, France has gone from 324,000 international students to 358,000.[62] This is a significant increase of more than 10.4%. while Germany was the fifth largest receiver, with 244,575 international students. In the winter semester 2017–18, Germany received 374,583 international students from overseas pursuing higher education and the Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) is 5.46%.[63][30] Since the 2016/17 academic year, the number of foreign students attending university in Germany has constantly risen, climbing from 358,895 students five years ago to 411,601 students last year.[64]

With the Franco-German University, the two countries have established a framework for cooperation between their universities, enabling students to participate in specific Franco-German courses of study across borders.[65]

The top 10 countries sending students to France in 2016 are listed below.[30]

| Rank | Country | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 28,012 | 12.4% | |

| 2 | 23,378 | 10.4% | |

| 3 | 17,008 | 7.5% | |

| 4 | 9,403 | 4.2% | |

| 5 | 8,535 | 3.8% | |

| 6 | 7,428 | 3.3% | |

| 7 | 6,338 | 2.8% | |

| 8 | 5,143 | 2.3% | |

| 9 | 4,620 | 2.0% | |

| 10 | 4,550 | 2.0% |

The top 10 countries sending students to Germany in 2015 are listed below.[30]

| Rank | Country | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 23,616 | 12.2% | |

| 2 | 9,953 | 5.1% | |

| 3 | 9,896 | 5.1% | |

| 4 | 9,574 | 4.9% | |

| 5 | 6,955 | 3.6% | |

| 6 | 6,301 | 3.2% | |

| 7 | 6,293 | 3.2% | |

| 8 | 5,850 | 3.0% | |

| 9 | 5,657 | 2.9% | |

| 10 | 5,508 | 2.8% |

United Kingdom

Top 15 countries and regions sending students to the United Kingdom in 2021/22 are listed below.[66]

| Rank | Place of origin | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 151,690 | 22.3% | |

| 2 | 126,535 | 18.6% | |

| 3 | 44,195 | 6.5% | |

| 4 | 23,075 | 3.4% | |

| 5 | 22,990 | 3.4% | |

| 6 | 17,630 | 2.6% | |

| 7 | 12,700 | 1.9% | |

| 8 | 12,135 | 1.8% | |

| 9 | 11,870 | 1.7% | |

| 10 | 11,320 | 1.7% | |

| 11 | 10,330 | 1.5% | |

| 12 | 9,915 | 1.5% | |

| 13 | 9,855 | 1.4% | |

| 14 | 8,915 | 1.3% | |

| 15 | 8,750 | 1.3% | |

| Others | 182,495 | 26.8% | |

| Total | 679,970 | 100% | |

Netherlands

As of 2017, 81,000 international students studied in the Netherlands, compromising 11.6 per cent of the higher education student population across all degree levels (bachelors, masters, and PhD students). Of these students, 12,500 students or 15.4% were Dutch nationals who had studied elsewhere previously. Most international students in the Netherlands come from European Union countries (roughly three-fourths), with the largest segment of that population coming from Germany. Of the non-EU students, the largest portion is composed of Chinese students. Two-thirds of all international students come to the Netherlands for their bachelor's degree.[67]

Russia

Russia, since the Soviet times, has been a hub for international students, mainly from the developing world. It is the world's fifth-leading destination for international students, hosting roughly 300 thousand in 2019.[68]

The top 10 countries sending students to Russia in 2019 are listed below.[68]

| Rank | Country | Number of Students |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 71,368 | |

| 2 | 27,889 | |

| 3 | 27,397 | |

| 4 | 21,397 | |

| 5 | 21,609 | |

| 6 | 18,531 | |

| 7 | 12,501 | |

| 8 | 11,614 | |

| 9 | 10,946 | |

| 10 | 7,291 |

North America

Canada

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) reckons that as of December 2019, there were 642,480 international students which is a 13% increase from the previous year.[69] In 2019, 30% of the international students in Canada were from India and 25% were from China.[70] The newest Canadian government International Education Strategy (IES) for the period 2019-2024 includes a commitment to diversify inbound students and distribute them more equally across the country rather than having a strong concentration in a few cities.[71]

Top 15 countries and regions sending students to Canada in 2019 are listed below.[72]

| Rank | Country | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 219,855 | 34.2% | |

| 2 | 141,400 | 22.0% | |

| 3 | 24,180 | 3.8% | |

| 4 | 24,045 | 3.7% | |

| 5 | 21,595 | 3.4% | |

| 6 | 15,015 | 2.3% | |

| 7 | 14,745 | 2.3% | |

| 8 | 14,560 | 2.3% | |

| 9 | 11,985 | 1.9% | |

| 10 | 8,710 | 1.4% | |

| 11 | 8,490 | 1.3% | |

| 12 | 8,485 | 1.3% | |

| 13 | 7,770 | 1.2% | |

| 14 | 5,620 | 0.9% | |

| 15 | 5,125 | 0.8% | |

| Others | 110,900 | 17,3% | |

| Total | 642,480 | 100% | |

United States

Around 750,000 Chinese and 400,000 Indian students apply to overseas higher education institutions annually.[73][74] New enrollment of undergraduate and graduate foreign students at American universities and colleges for 2016-17 declined by 2.1% or nearly 5,000 students which translates into a potential revenue of US$125 million for the first year of studies alone.[75] Much of the increase in international students in the US during 2013–2014 was fueled by undergraduate students from China. The number of Chinese students increased to 31 per cent of all foreign students in the US, the highest concentration of any one country since the Institute of International Education began collecting data on international students in 1948.[76] This is changing quickly with demographic projections showing a large impending decrease in volumes of students from China and Russia and steady increases in students from India and Africa.

The number of foreign students in tertiary (university or college) education is also rapidly increasing as higher education becomes an increasingly global venture.[77] During 2014–15, 974,926 foreign students came to study in the US, which is almost double the population from 2005. For several decades Chinese students have been the largest demographic amongst foreign students. The top 10 sending places of origin and percentage of total foreign student enrollment are: China, India, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Canada, Brazil, Taiwan, Japan, Vietnam, and Mexico. The total number of foreign students from all places of origin by field of study are: Business/Management, Engineering, Mathematics and Computer Sciences, Social Sciences, Physical and Life Sciences, Humanities, Fine and Applied Arts, Health Professions, Education, and Agriculture.[78]

Top 15 sending places of origin and percentage of total foreign student enrollment 2018-2019[79][80]

| Rank | Place of origin | Number of students | Per cent of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 369,548 | 33.7% | |

| 2 | 202,014 | 18.4% | |

| 3 | 52,250 | 4.8% | |

| 4 | 37,080 | 3.4% | |

| 5 | 26,122 | 2.4% | |

| 6 | 24,392 | 2.2% | |

| 7 | 23,369 | 2.1% | |

| 8 | 18,105 | 1.7% | |

| 9 | 16,059 | 1.5% | |

| 10 | 15,229 | 1.4% | |

| 11 | 13,423 | 1.2% | |

| 12 | 13,229 | 1.2% | |

| 13 | 12,142 | 1.1% | |

| 14 | 11,146 | 1.0% | |

| 15 | 10,159 | 0.9% |

Total number of foreign students from all places of origin by field of study 2015-2016

| Rank | Field of Study | Number of Students | Per cent of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Business and Management | 200,312 | 19.2% |

| 2 | Engineering | 216,932 | 20.8% |

| 3 | Other/Unspecified Subject Areas | 185,107 | 17.7% |

| 4 | Mathematics and Computer Sciences | 141,651 | 13.6% |

| 5 | Social Sciences | 81,304 | 7.8% |

| 6 | Physical and Life Sciences | 75,385 | 7.2% |

| 7 | Humanities | 17,664 | 1.7% |

| 8 | Fine and Applied Arts | 59,736 | 5.7% |

| 9 | Health Professions | 33,947 | 3.3% |

| 10 | Education | 19,483 | 1.9% |

| 11 | Agriculture | 12,318 | 1.2% |

The number of US visas issued to Chinese students to study at US universities has increased by 30 per cent, from more than 98,000 in 2009 to nearly 128,000 in October 2010, placing China as the top country of origin for foreign students, according to the "2010 Open Doors Report" published on the US Embassy in China website. The number of Chinese students increased. Overall, the total number of foreign students with a US visa to study at colleges and universities increased by 3 per cent to a record high of nearly 691,000 in the 2009/2010 academic year. The 30 per cent increase in Chinese student enrolment was the main contributor to that year's growth, and now Chinese students account for more than 18 per cent of the total foreign students.[81]

Requirements

Prospective foreign students are usually required to sit for language tests, such as Cambridge English: First,[82] Cambridge English: Advanced,[83] Cambridge English: Proficiency,[84] IELTS, TOEFL, iTEP, PTE Academic,[85] DELF[86] or DELE,[87] before they are admitted. Tests notwithstanding, while some international students already possess an excellent command of the local language upon arrival, some find their language ability, considered excellent domestically, inadequate for the purpose of understanding lectures, and/or of conveying oneself fluently in rapid conversations. A research report commissioned by NAFSA: Association of International Educators investigated the scope of third-party providers offerings intensive English preparation programs with academic credit for international students in the United States.[88] These pathway programs are designed to recruit and support international students needing additional help with English and academic preparation before matriculating to a degree program.

Student visa

Generally, foreign students as citizens of other countries are required to obtain a student visa, which ascertains their legal status for staying in the second country.[89] In the United States, before students come to the country, the students must select a school to attend to qualify for a student visa. The course of study and the type of school a foreign student plans to attend determine whether an F-1 visa or an M-1 visa is needed. Each student visa applicant must prove they have the financial ability to pay for their tuition, books and living expenses while they study in the states.[90]

Economic impact

Research from the National Association of Foreign Student Advisers (NAFSA) shows the economic benefits of the increasing international higher-education enrollment in the United States. According to their 2021–2022 academic year analysis, nearly one million international students contributed $33.8 billion to the US economy and 335,000 jobs. This represents almost a 19% increase in dollars compared to the previous year. International students contribute more than job and monetary gains to the economy. “The increase in economic activity is certainly positive news but it should be kept in perspective: it shows we’ve only regained about half the ground lost in the previous academic year,” said Dr. Esther D. Brimmer, NAFSA executive director and CEO. “We must not be complacent that this upward trend will automatically continue. [91] According to NAFSA's research, their diverse views contribute to technological innovation has increased America's ability to compete in the global economy.

On the other hand, international students have faced suspicions of involvement in economic and industrial espionage.[92]

Higher education marketing

Marketing of higher education is a well-entrenched macro process today, especially in the major English-speaking nations: Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA. One of the major factors behind the worldwide evolution of educational marketing could be globalization, which has dramatically shrunken the world. Due to intensifying competition for overseas students amongst MESDCs, i.e. major English-speaking destination countries, higher educational institutions recognize the significance of marketing themselves, in the international arena.[93] To build sustainable international student recruitment strategies Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) need to diversify the markets from which they recruit, both to take advantage of future growth potential from emerging markets, and to reduce dependency on – and exposure to risk from – major markets such as China, India and Nigeria, where demand has proven to be volatile.[94] For recruitment strategies, there are some approaches that higher education institutions adopt to ensure stable enrollments of international students, such as developing university preparation programs, like the Global Assessment Certificate (GAC) Program, and launching international branch campuses in foreign countries.

Global Assessment Certificate (GAC) Program

The Global Assessment Certification (GAC) Program is a university preparation program, developed and provided by ACT Education Solution, Ltd., for the purpose of helping students to prepare for admission and enrollment overseas.[78] The program helps students from non-English speaking backgrounds to prepare for university-level study, so they are able to successfully finish a bachelor's degree at university. Students who complete the GAC program have the opportunity to be admitted to 120 so called Pathway Universities, located in destinations including the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.[95] Mainly, the program consists of curriculums, such as Academic English, Mathematics, Computing, Study Skills, Business, Science and Social Science. Moreover, the program also provides the opportunity to get prepared for the ACT exam and English Proficiency tests like TOEFL and IELTS.[96]

Foreign branch campuses

Opening international branch campuses is a new strategy for recruiting foreign students in other countries in order to build strong global outreach by overcoming the limitations of physical distance. Indeed, opening branch campuses plays a significant role of widening the landscape of the higher education. In the past, along with high demand for higher education, many universities in the United States established their branch campuses in foreign countries.[97] According to a report by the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education (OBHE), there was a 43% increase in the number of foreign branch campuses in the worldwide scale since 2006. American higher education institutions mostly take a dominant position in growth rate and the number of foreign branch campuses, accounting for almost 50 per cent of current foreign branch campuses.[98] However, some research reports have recently said foreign branch campuses are facing several challenges and setbacks, for example interference of local government,[99] sustainability problems, and long-term prospects like damage on academic reputations and finance.

Challenges for foreign students in English-speaking countries

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (August 2022) |

There is a trend for more and more students to go abroad to study in the US, Canada, UK, and Australia to gain a broader education.[citation needed] English is the only common language spoken at universities in these countries, with the most significant exception being Francophone universities in Canada. International students need not only to acquire good communication skills and fluent English, both in writing and speaking, but also to absorb the Western academic writing culture in style, structure, reference, and the local policy toward academic integrity in academic writing. International students may have difficulty completing satisfactory assignments because of the difficulty with grammar and spelling, differences in culture, or a lack of confidence in English academic writing. Insightful opinions may lose the original meaning when transformed from the student's native language to English. Even if international students acquire good scores in English proficiency exams or are able to communicate with native students frequently in class, they often find that the wording and formatting of academic papers in English-speaking universities are different from what they are used to due to certain cultural abstractions.[clarification needed] Students who experience this discrepancy get lower scores for adaptability to new environment and higher scores for anxiety. Instead of the mood,[clarification needed] students who were further away from home would be more willing to go back home and regress from their aims in life;[clarification needed] this hardship can lead to depression. This will cause the international student to have a bad experience of the foreign country and its culture, and will more likely not recommend the country to others. Partly this is due to the academic contagions[clarification needed] of the foreign university like not integrating contrastive rhetoric aspect,[clarification needed] low support for adaptation like providing opportunities for developing their employability skills[100] to better their English in a non-competitive and meaningful way.[101]

Most foreign students encounter difficulties in language use. Such issues make it difficult for the student to make domestic[clarification needed] friends and gain familiarity with the local culture. Sometimes, these language barriers can subject international students to ignorance or disrespect from native speakers.[102] Most international students also lack support groups in the country where they are studying. Although all colleges in North America that are in student exchange programs do have an International Student Office, it sometimes does not have the resources and capability[clarification needed] to consider their students' individual needs when it comes to adapting to the new environment. The more students a particular college has who come from the same country, the better the support is for getting involved in the new culture.[103]

Foreign students face several challenges in their academic studies at North American universities. Studies have shown that these challenges include several different factors: inadequate English proficiency; unfamiliarity with North American culture; lack of appropriate study skills or strategies; academic learning anxiety; low social self-efficacy; financial difficulties; and separation from family and friends.[104] Despite the general perception that American culture is diverse rather than homogenous, the American ideology of cultural homogeneity has been alleged to imply an American mindset that because Eurocentric cultures are superior to others, people with different cultures should conform to the dominant monocultural canon and norms.[105]

US colleges and universities have long welcomed students from China, whose higher education system cannot meet the demand.[clarification needed] 10 million students throughout China take the national college entrance test, competing for 5.7 million university places. Because foreign undergraduates typically fail to qualify for US federal aid, colleges can provide only limited financial help. Now, thanks to China's booming economy in recent years, more Chinese families can afford to pay.

US colleges also face challenges abroad. Worries about fraud on test scores and transcripts make occasional headlines. And even Chinese students who score highly on an English-language proficiency test may not be able to speak or write well enough to stay up to speed in a US classroom, where essay writing and discussions are common.[106] Chinese international students face other challenges besides language proficiency. The Chinese educational structure focuses on exam-oriented education, with educational thinking and activities aimed towards meeting the entrance examination. Students become more focused on exam performance, and teachers are inclined to focus on lecturing to teach students what may be on the test. In addition, "parents are also convinced that the more students listened to the lectures, the better they would score on the finals."[107] With more than 304,040 Chinese students enrolled in the US in 2014/15, China is by far the leading source of international students at American universities and colleges; however, there are three waves of growth in Chinese students in the US.[108]

Each of the three waves differs in terms of needs and expectations and corresponding support services needed. Unfortunately, many higher education institutions have not adapted to the changing needs.[109] It is no surprise that many Chinese students are now questioning if it is worth investing in studying abroad.[110]

International students also face cross-cultural barriers that hinder their ability to succeed in a new environment.[111] For example, there are differences in terms of receiving and giving feedback, which influences academic engagement and even the job and internship search approach of international students.[112]

Transparency is an issue that international students face when coming across activities within class, specifically when it comes to group discussions, it may be a bigger obstacle. Firstly, the issue of how topics being discussed may not need further elaboration when it comes to local students and for an international student, the ability of the student to be able to understand and contribute may diminish in return. This may be due to the feeling of dismissal via the appearance of lack of interest in their opinion. Another would be the failure of expected scaffolding during group discussions when it comes to international students. This is due to the need for a developed understanding of local culture, or "cultural facts" as represented by Kim. This represents the knowledge of humor, vernacular, or simple connotations in speech that may allow international students to further develop an understanding of a given topic.[113]

Plagiarism is the most serious offense in academia.[114] Plagiarism has two subtle forms, one of which includes the omission of elements required for proper citations and references.[115] The second form is unacknowledged use or incorporation of another person's work or achievement. Violation of either form can result in a student's expulsion. International students from some cultures lack the concept of plagiarism.[116] Most of them are unfamiliar with American academic standards and colleges are not good about giving a clear definition of the word's meaning. For example, many international students don't know using even one sentence of someone else's work can be considered plagiarism. Most colleges give students an E on their plagiarized assignments and future offenses often result in failing class or being kicked out of university.

Mental wellness

International students studying in a foreign country face a life-altering event which can cause distress that can potentially affect their mental wellness. Many students report homesickness and loneliness in their initial transition, experience isolation from peers and struggle with understanding cultural differences while staying abroad. In certain cultures, mental illness is seen as a sign of weakness. Because of this, international students believe they can prevail through their struggles alone without help, which can lead to a decrease in mental wellness.[117]

There are two common symptoms among international students from China in particular: 45 per cent of the students faced depression and 29 per cent of the students faced anxiety.[118] Stressors that lead international students to struggle with anxiety are rooted in numerous causes, including academic pressures, financial issues, adapting to a new culture, creating friendships, and feelings of loneliness.[119] International students are also more likely to rely on peers for support through their transition than teachers or adult peers.[120] If the student is unable to make friends in their new environment, they will struggle more with their transition than an international student who has established relationships with their peers.[121] During the COVID-19 pandemic, many international students started remote learning and had to overcome time differences to take classes online, which further led to sleep disruption, social isolation, and thus, higher rates of mental health symptoms.[122]

Language and communication barriers have been noted to add to student anxiety and stress.[123] International students face language discrimination, which may exacerbate mental health symptoms. Evidence has not conclusively shown that language discrimination is a greater risk factor than discrimination against foreigners. However, there has not been any conclusive evidence to show whether language discrimination plays a significantly larger role than simple foreigner discrimination.[121]

Since international students are less likely to use individual counseling provided by the university.[124] and may experience even more intense stigmas against seeking professional help,[125] group-oriented ways of reaching students may be more helpful.[126] Group activities, like collaborative workshops and cultural exchange groups, can introduce a sense of community among the students.[127][128] In addition, efforts can be placed to improve awareness and accessibility to mental wellness resources and counseling services.[122][129] Social workers, faculty, and academic staff can be educated beforehand to provide an adequate support for them.[130]

Study abroad

This article may need to be cleaned up. It has been merged from Study abroad. |

Studying abroad is the act of a student pursuing educational opportunities in a country other than one's own.[131] This can include primary, secondary and post-secondary students. A 2012 study showed number of students studying abroad represents about 9.4% of all students enrolled at institutions of higher education in the United States[132][133] and it is a part of experience economy.[134][135]

Studying abroad is a valuable program for international students as it is intended to increase the students' knowledge and understanding of other cultures. International education not only helps students with their language and communicating skills. It also encourages students to develop a different perspective and cross-cultural understanding of their studies which will further their education and benefit them in their career.[136][137] The main factors that determine the outcome quality of international studies are transaction dynamics (between the environmental conditions and the international student), quality of environment, and the student's coping behavior.

Distinctions in classroom culture

This article is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. (August 2022) |

Certain distinctions and differences can become sources of culture shock and cultural misunderstandings that can lead a student to inhibit adaptation and adjustment. For example, a key requirement in many American institutions is participation in classroom discussions and activities. Failure to participate in the classroom with faculty can be a serious obstacle to good grades. This is particularly a problem for international students who come from countries with the view that professors are to be held in awe, and not questioned. Then the problem can be reflected in the grades given for class participation. Lack of participation can be interpreted by some American faculty as failure to learn the course content or disinterest in the topic. This is important in American classrooms which ideally require students to go through double loop of learning where they have to re-frame their dispositions and form a framework of inner agency.[138] Some of the identified distinctions identified by the American Association of International Educators are:[139]

- Semester system has three models: they are (1) the semester system comprising two terms, one in fall and one in winter/spring (summer term is not required); (2) the trimester system comprising three terms that includes summer (one of these terms can be a term of vacation); and (3) the quarter system comprising the four terms of fall, winter, spring, and summer, and in which the student can choose one of them to take as a vacation.

- The schedule of the classes is a standard five-day week for classes, but the instruction hours in a week may be divided into a variety of models. Two common models of choice are Monday/Wednesday/Friday (MWF) and Tuesday/Thursday (TT) model. As a result, the class hours per week are the same, but the length of time per class for the MWF will be different from the TT.

- Most foreign institutes value the ideologies of fairness and independence. These standards ensure the rights and responsibilities of all students, regardless of background. Most institutions that define the rights and responsibilities of their students also provide a code of conduct to guide their behavior, because independence and freedom come with responsibilities.

- Certain immigration regulations allow international students to gain practical experience during their studies through employment in their field of study like an internship during study, and at other times for one year of employment after the student completes their studies. The eligibility factors are often disseminated through international students office at the college or university.

- Faculty differ both in rank and by the duration of their contracts. (1) Distinguished teaching and research faculty hold the most honored rank among faculty. They typically have the doctoral degree and are usually tenured (i.e. on a permanent contract with the school until they retire) and record of their personal excellence accounts for their standing; (2) Emeritus professors are honored faculty who have retired from the university but continue to teach or undertake research at colleges and universities; (3) Full professors are also tenured and hold the doctoral degree. It is length of service and the support of departmental chairpersons, colleagues, and administrators that leads to the promotion to this rank; (4) Associate professors typically hold the doctoral degree and are the most recent to receive tenure; (5) Assistant professors may or may not yet have their doctoral degrees and have held their teaching or research posts for less than seven years; (6) Instructors are usually the newest faculty. They may or may not hold the doctoral degree and are working towards tenure; (7) Adjunct professors and visiting professors may hold professorial rank at another institution. They are not tenured (usually retained on a year by year contract) and they are often honored members of the university community.

- Most institutes that accept international students have faculty who are leaders that can integrate the best elements of teacher-centered and learner centered pedagogical styles that integrates and leads students of every background to a path of success. They are careful not to obstruct a student with their own personality or achievements and maintain a resourceful, open and supportive "holding environment". Simplified, meaningful resource dissemination and engaging students in participatory and active learning is the key to this mixed learning. Lack of skill in handling such pedagogical methods might result in straining the students from a "polyvagal perspective" (taking classes in a restless pace disregarding the quality and quantity of the information transferred, which translates as lack of internal agency to make students learn meaningful content by being an educational agent - lack of teacher agency)[140] and at other instances downgrade into a liberal laissez-faire style which might negatively affect students' performance. The skill of the tutor is exemplified in many forms one such as when they are able to keep some students from dominating (attention seeking, disruptive or disrespectful) and to draw in those who are reticent in a participatory section.

- Students are expected to know the content of their courses from the class website (structure of the course, frame of reference, jargon) and to think independently about it and to express their own perspectives and opinions in class and in their written work. Open disagreement is a sign of violent intentions in certain cultures and in other cultures it is merely expressing one's opinion; this aspect can be challenging if proper people skills are absent in the group and group development is not given importance. Similar is the case with asking questions: in certain classroom cultures it is tolerated to ask vague questions and this is interpreted as a sign of interest from the student whereas in other cultures asking vague questions is a display of ignorance in public that results in loss of face and embarrassment, even if this behavior is counterproductive for a learning environment, it is largely dependent upon the transaction dynamics in classroom cultures. There are also certain institutes and cultures that disallow student discussion at certain topics and keep limitations to what can be discussed and punitive means for deterring from topics that shouldn't be discussed.[141] But often direct communication is considered vital for academic survival.

- Foreign university programs differ from structured programs of universities in certain countries. In each quarter the student is given choice to select the courses they deem important to them for gaining credits. There is no proportion for the number of courses that a student can take in each term; however, program fees paid at a single time can lead to fees deduction in each quarter. In general, students are not recommended to take many courses at a time as they require to gain a certain number of credits to pass a quarter which is dependent upon the grades that they obtain from the courses, and these credits have little to do with the actual credit hours spent for each courses. For the courses students have to pre-register as they are not automatically assigned. Though it is an open structure for course selections, students might be required to take certain compulsory courses for the program as maintained by departments for degree standardization.

- Foreign institutions differ in their requirement of the content that a student is required to be familiarized with, and this difference is identifiable in programs which have similar objectives and structures of different universities. Some may be professionally oriented and thus give importance to depth in certain areas, and some might be for providing a breadth of knowledge on the subject. Commonly, some institutes might require the student to master the essentials of a subject as a whole, while others might require the student to master large quantities of content on the subject which might not seem practical in a framework of short period of time (An example is 10,000-Hour Rule).[142] More accessible institutions provide a syllabus of their previous and current programs and courses for better pre- and post- program communication.

- Classroom etiquette may differ from institute to institute. In western institutes the old standard of practice for students to address faculty is by their last name and the title "Professor", but it is not uncommon for faculty to be on a first-name basis with students today. However, it is a good etiquette to check with the faculty member before addressing him or her by their first name only. Both students and faculty often dress very informally, and it is not unusual for faculty to roam the classroom while talking or to sit on the edge of a table in a very relaxed posture. Relaxed dress and posture are not, however, signs of relaxed standards of performance. Sometimes faculty, administrators, and even staff may sometimes hold receptions or dinners for their students. In that case, students should ask what the dress should be for the occasion; sometimes students will be expected to wear professional dress (suit coat and tie for men, and a suit or more formal dresses for women). Faculty would not care even if they elicit the need of participation in the classroom or are personally involved with students; even if they engage students in frameworks/styles the student might understand the topic. This is because the faculty-student relationship is considered to be professional. Relationships in the West are most often determined by some kind of function. Here the function is guidance, education and skill development.

- In occidental institutions students are evaluated in many ways, including exams, papers, lab reports, simulation results, oral presentations, attendance and participation in classroom discussion. The instructors use a variety of types of exams, including multiple choice, short answer, and essay. Most adept instructors provide guides or models of assignment construction, framing and asking questions about how to prepare for their exams. Most students are expected to be creative in presentation (to avoid similarity in paper submissions), systematic in formatting (citation: Style guide) and invested for drawing and providing positive individualism to the group/class (group purpose, role identity for autonomy, positive thinking, value oriented responsible self-expression, etc. vs. attendant selfishness, alienation, divisiveness, etc.) aligned with the common development objective.

- Relationships are an important part of the foreign academic experience and for healthy social support. Relationships with faculty (instructors and academic advisors) are very important for academic success and for bridging the cultural gap. But in off-campus venues, the student can appreciate their life outside of campus, and every time they view one another as individuals, avoid asking favors that can affect teacher-student comfort zones and expect cautiousness from them in an attempt to avoid notions of favoritism and friendliness to break down barriers of role and culture.

A key factor in international academic success is learning approaches that can be taken on a matter from one another and simultaneously assimilating inter-cultural experiences.

Titles and roles in administrative structure

- The vice-chancellor or vice-president for academic affairs manages the various schools and departments.

- The council of deans oversees the separate schools, institutes, and programs offered by the university or college.

- The departmental chairperson manages the affairs of the separate departments in each school or college.

- Faculty is responsible for teaching and research in and beyond the classroom.

- Secretaries and technical support staff in foreign countries have much authority than their counterparts in certain countries. They are treated respectfully by faculty and students alike.[139]

Accommodation

Accommodation is a major factor that determines study abroad experience.[143][144]

Host family

A host family volunteers to house a student during their program. The family receives payment for hosting. Students are responsible for their own spending, including school fees, uniform, text books, internet, and phone calls. Host families could be family units with or without children or retired couples; most programs require one host to be at least 25 years of age. The host families are well prepared to experience a new culture and give a new cultural experience to the student. A student could live with more than one family during their international study program to expand their knowledge and experience more of the new culture. Host families are responsible for providing a room, meals, and a stable family environment for the student. Most international student advisory's allow for a switch of hosts if problems arise.

Housing

An international student involved in study abroad program can choose to live on campus or off campus. Living off campus is a popular choice, because students are more independent and learn more about the new culture when they are on their own. Universities that host international students will offer assistance in obtaining accommodation. Universities in Asia have on-campus housing for international students on exchange or studying full-time. Temporary options include hostels, hotels, or renting. Homestays, paid accommodation with a host family, are available in some countries.

Coping in study abroad

The w-curve adjustment model

The w-curve model created by Gullahorn and Gullahorn (1963) is W shaped model that attempts to give a visual description of a travelers possible experience of culture shock when entering a new culture and the re-entry shock experienced when returning home. The model has seven stages. Further reviews of the model have been published.[145]

- Honeymoon Stage

- Hostility Stage

- Humorous/Rebounding Stage

- In-Sync Stage

- Ambivalence Stage

- Re-Entry Culture Shock Stage

- Re-Socialization Stage

Each stage of the model aims to prepare travellers for the rollercoaster of emotions that they may experience both while returning and traveling from a trip abroad. The hope in the creation of this model is to help prepare travelers for the negative feelings often associated with living in another culture. By doing so, it is the goal that these emotions will be better dealt with.[citation needed]

Positive affectivity

Affectivity is an emotional disposition: people who are high on positive affectivity experience positive emotions and moods like joy and excitement, and view the world, including themselves and other people, in a positive light. They tend to be cheerful, enthusiastic, lively, sociable, and energetic. Research has found that students studying abroad with a positive emotional tendency have higher satisfaction and interaction with the environment; they engage in the staying country's citizenship behaviours.[134][146]

Adjustment concepts

Being relevant to research on coping by international students, the concept of adjustment to a foreign work environment and its operationalisation has been the subject of broad methodological discussion.[147][148]

See also

- Apprentices mobility

- EducationUSA

- Erasmus programme

- F-1 Visa

- Fulbright Program

- Goodwill Scholarships

- International Baccalaureate

- International communication

- International education

- International Student Identity Card

- International student ministry

- International Students Day

- Japanese students in Britain

- Monbukagakusho Scholarship

- Pakistani students abroad

- Student exchange program

- Student migration

- Study abroad

- Indian students abroad

- Vulcanus in Japan

Organizations

- Brethren Colleges Abroad

- International Union of Students

- NAFSA: Association of International Educators

- Journal of International Students

References

- ^ "Other policy relevant indicators : Inbound internationally mobile students by continent of origin". UNESCO. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ^ "Glossary". Institute of International Education. 2018. Archived from the original on 17 August 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ^ "United States". www.iie.org. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Students and Employment | USCIS". www.uscis.gov. 31 March 2023. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

- ^ "Eligible countries | Erasmus+". erasmus-plus.ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "What is Erasmus and who can apply for the programme?". Basecamp. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Definition of "International students"". www150.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "I want to study in Canada for less than 6 months. Do I need a study permit?". www.cic.gc.ca. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Dictionary". www.studyaustralia.gov.au. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ "Japan". www.iie.org. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b Choudaha, Rahul (March 2017). "Three waves of international student mobility (1999-2020)". Studies in Higher Education. 42 (5): 825–832. doi:10.1080/03075079.2017.1293872. S2CID 151764990.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul (2 May 2018). "Nationalist Style Politics will Trigger A New Wave of International Mobility". Times Higher Education.

- ^ Lorin, Janet (17 November 2020). "Biden's Election Will Lure MBA Students Back to the U.S., But Not Overnight". Bloomberg.

- ^ "Booming student market proving a hot commodity". The Australian. 16 October 2019.

- ^ a b "Australian universities double down on international students". Macrobusiness. 1 November 2019.

- ^ "International Migration Outlook: SOPEMI 2010" (PDF). Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 May 2022.

- ^ "The CWTS Leiden Ranking 2020". leidenmadtrics.nl. 8 July 2020. Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2022". Times Higher Education. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul (12 March 2017). "Three waves of international student mobility explain the past, present and future trends". DrEducation. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul (26 May 2016). "Webinar on Transnational Education: Recording of the Online Discussion with Global Experts ~ DrEducation: Global Higher Education Research and Consulting". dreducation.com. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Mitchell, Nic (26 January 2018). "Global universities unprepared for sea change ahead". University World News.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul (2020). "Addressing the Affordability Crisis for International Students". Journal of International Students. 10 (2): iii–v. doi:10.32674/jis.v10i2.1969.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Explore Global Data".

- ^ "Explore Partner Data".

- ^ "Project Atlas".

- ^ "France hits 400,000 int'l student mark". 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "FRANCE SEES A RECORD RISE IN FOREIGN STUDENTS". 26 September 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- ^ "Education: Inbound internationally mobile students by continent of origin". data.uis.unesco.org. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d UNESCO Institute for Statistics. "Inbound internationally mobile students by continent of origin". Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ a b "2018年来华留学统计" (in Chinese). China Ministry of Education. 12 April 2019. Archived from the original on 15 April 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Saul, Stephanie (13 November 2017). "Fewer Foreign Students Are Coming to U.S., Survey Shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Tess Reidy (4 January 2017). "Anxious international students turn away from UK". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Victoria Breeze (27 June 2017). "China tops US and UK as destination for anglophone African students". The Conversation. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b c 忠建丰 (Zhong Jianfeng), ed. (1 March 2017). "2016年度我国来华留学生情况统计 (Statistics of International Students in China in 2016)" (in Chinese). China Ministry of Education. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Growing number of foreign students choosing to study in China for a degree across multiple disciplines". China Ministry of Education. 3 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "China announces new push for elite university status". ICEF Monintor. 4 October 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Higher Education in Asia: Expanding Out, Expanding Up" (PDF). UNESCO. 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b c "Overview of Study Abroad in China". Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Education and the exercise of soft power in China". ICEF Monitor. 13 January 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Lily Kuo (14 December 2017). "Beijing is cultivating the next generation of African elites by training them in China". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ a b "All India Survey on Higher Education 2019-20" (PDF). Ministry of Education. Retrieved 13 November 2021.

- ^ Prashant K. Nanda (23 September 2019). "Where does India get foreign students from?". LiveMint. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ K V Priya (19 April 2018). "'Study in India' to attract foreign students". mediainindia.eu. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

- ^ "55,000 international students studying in Iran". 25 May 2018.

- ^ https://www.irna.ir/amp/85175009/

- ^ "مقررات آموزشی پذیرش حشدالشعبیها مانند سایر دانشجویان خارجی است - ایسنا".

- ^ "رئیس دانشگاه تهران از پذیرش نیروهای حشدالشعبی دفاع کرد – Dw – ۱۴۰۲/۴/۲۶".

- ^ "جشن فارغ التحصیلی دانشجویان خارجی + فیلم".

- ^ "300000 Foreign Students Plan". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ [2]

- ^ "2022(令和4)年度外国人留学生在籍状況調査結果|外国人留学生在籍状況調査|留学生に関する調査|日本留学情報サイト Study in Japan".

- ^ "外国人留学生在籍状況調査|留学生に関する調査|日本留学情報サイト Study in Japan".

- ^ "World Education Services Annual Report 2018" (PDF). World Education Services. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2010..

- ^ "UNESCO Institute for Statistics: UNESCO Institute for Statistics". Uis.unesco.org. 4 December 2009. Archived from the original on 4 October 2009. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Beyond 20/20 WDS - Report Folders". Stats.uis.unesco.org. Archived from the original on 19 September 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Empowering People to Innovate". The OECD Innovation Strategy. OECD iLibrary. 28 May 2010. pp. 55–85. doi:10.1787/9789264083479-5-en. ISBN 9789264084704. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "International Student Data 2021". Australian Government - Department of Education, Skills and Employment. 2021.

- ^ Gothe-Snape, Jackson (26 July 2018). "Record number of international students sticking around on work visas". ABC News.

- ^ "International student numbers by country, by state and territory". Australian Government Department of Education.

- ^ "International student numbers by country, by state and territory". Australian Government Department of Education.

- ^ "Key Figures February 2020" (PDF). Campus France. 2020.

- ^ Team, BMBF's Data Portal. "Table Search - Search results - BMBF's Data Portal". Data Portal of Federal Ministry of Education and Research - BMBF.

- ^ "IN STATS: Fewer international students join German universities amid pandemic". The Local. 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Franco-German University - facts & figures". dfh-ufa.org. Archived from the original on 1 March 2018. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- ^ "Where do HE students come from?: Non-UK HE students by HE provider and country of domicile". hesa.ac.uk. Higher Education Statistics Authority. Retrieved 12 February 2023.

- ^ "International students". CBS Netherlands. 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- ^ a b "Global Flow of Tertiary-Level Students". UNESCO. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "International students in Canada continue to grow in 2019". Canadian Bureau for International Education. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Facts and Figures". Canadian Bureau for International Education. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ "Canada's International Education Strategy (2019-2024)". 22 August 2019.

- ^ El-Assal, Kareem (20 February 2020). "642,000 international students: Canada now ranks 3rd globally in foreign student attraction". CIC News.

- ^ "How many Indian and Chinese students go abroad every year?". DrEducation.com. 20 August 2013. Retrieved 28 August 2012.

- ^ "Recueil de données mondiales sur l'éducation 2010 : Statistiques comparées sur l'éducation dans le monde" (in French). UNESCO. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2011.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul. "How the US can stem decline in foreign students - University World News". universityworldnews.com. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Haynie, Devon (17 November 2014). "Number of International College Students Continues to Climb". U.S. News & World Report Education.

- ^ "he Shape of Things to Come: Higher Education Global Trends and Emerging Opportunities to 2020" (PDF). British Council. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2022.

- ^ a b "International Students in the United States". Project Atlas. Open Doors Report. Archived from the original on 27 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Duffin, Erin (17 November 2021). "International students in the U.S., by country of origin 2020/21". Statista.

- ^ "Number of International Students in the United States Hits All-Time High". IIE. 18 November 2019.

- ^ Marklein, Mary Beth (8 December 2009). "Chinese college students flocking to U.S. campuses". USA Today.

- ^ "B2 First". Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "C1 Advanced". Cambridge. Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "Cambridge English: Proficiency (CPE)". Retrieved 15 April 2016.

- ^ "English Testing Advice for Studying in the USA". US Journal. n.d. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Take a test or a certification to prove your proficiency". French Higher Education. n.d.

- ^ "What are DELEs?". Study in Spain. n.d. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "NAFSA research on landscape of third-party pathway partnerships in the US". dreducation.com. 24 May 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ "Student Visa". travel.state.gov. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Durrani, Anayat (15 December 2020). "How to Demonstrate Financial Ability as an International Student". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Ruffner, Matt (14 November 2022). "Findings Underscore need for a national 'road map' to guide recovery and future growth". www.nafsa.org. Retrieved 14 March 2023.

- ^

Ha, Melodie (3 August 2018). "Hidden Spies: Countering the Chinese Intelligence Threat". The Diplomat. ISSN 1446-697X. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

Earlier this year, Federal Bureau of Investigations [sic] (FBI) Director Christopher Wray asserted in testimony before the Senate intelligence committee that Chinese international students, especially those in advanced STEM fields, pose counterintelligence risks to U.S. national security. 'They're exploiting the very open research and development environment that we have... they're taking advantage of it,' Wray said during the hearing. [...] The Trump administration is taking steps forward to counter Chinese economic and industrial espionage, but painting every Chinese student on U.S. campuses as an intelligence threat is not the way to do it.

- ^ "Wrest Corporation - International Internship & MBA Consultant Delhi". Archived from the original on 23 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- ^ "International Student Survey". Hobsons. Archived from the original on 23 May 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ "2016 GAC Pathway University Handbook" (PDF). ACT International Services. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "What is in the Global Assessment Certificate™ program?". Archived from the original on 20 June 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Clifford, Megan. "Assessing the Feasibility of Foreign Branch Campuses" (PDF). rand.org. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Becker, Rosa (2010). "International Branch Campuses: New Trends and Directions". Branch Campuses & Transnational Higher Education (58). doi:10.6017/ihe.2010.58.8464. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ María Eugenia Miranda (3 June 2014). "International Branch Campuses Producing Opportunities, Headaches". Diverse. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Ammigan, Ravichandran; Dennis, John Lawrence; Jones, Elspeth (2021). "The Differential Impact of Learning Experiences on International Student Satisfaction and Institutional Recommendation". Journal of International Students. 11 (2). doi:10.32674/jis.v11i2.2038. S2CID 234428772. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Top Chinese Universities in Medicine, 2013". CUCAS. 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ Lindemann, Stephanie (6 September 2002). "Listening with an attitude: A model of native-speaker comprehension of non-native speakers in the United States". Language in Society. 31 (3): 419–441. doi:10.1017/S0047404502020286. S2CID 145064535. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Beck, Richard; Taylor, Cathy; Robbins, Marla (June 2003). "Missing home: Sociotropy and autonomy and their relationship to psychological distress and homesickness in college freshmen". Anxiety, Stress & Coping. 16 (2): 155–166. doi:10.1080/10615806.2003.10382970. S2CID 144609852.

- ^ Huang, Jinyan; Brown, Kathleen (2009). "Cultural Factors Affecting Chinese ESL Students' Academic Learning". Education. 129 (4): 643–653. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ Hsieh, Min-Hua (2007). "Challenges for International Students in Higher Education: One Student's Narrated Story of Invisibility and Struggle". College Student Journal. 41 (2): 379–391. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "Number of Chinese students applying for a US Visa increases". American Visa Bureau. 16 November 2010. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010.

- ^ Bista, Krishna (23 June 2011). "A First-Person Explanation of Why Some International Students Are Silent in the U.S. Classroom". Faculty Focus.

- ^ "Three Waves of Chinese Students since 1999". Interedge. 20 April 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul; Hu, Di (March 2016). "Higher Education Must Go Beyond Recruitment and Immigration Compliance of International Students". Forbes.

- ^ Choudaha, Rahul. "Enhancing success and experiences of Chinese students for sustainable enrollment strategies ~ DrEducation: Global Higher Education Research and Consulting". dreducation.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ "Intercultural Competence – International Student Success Training and Resources". resources.interedge.org. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Hu, Di (10 April 2016). "Navigate the Cross-cultural Map: Feedback". International Student Success Training and Resources. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Kim, Hye Yeong (June 2011). "International graduate students' difficulties: graduate classes as a community of practices". Teaching in Higher Education. 16 (3): 281–292. doi:10.1080/13562517.2010.524922. ISSN 1356-2517. S2CID 145611006.

- ^ "The Problems with Plagiarism". Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ "How to Recognize Plagiarism: Tutorials and Tests". Archived from the original on 2 April 2016. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Farhang, Kia. "For some international students, 'plagiarism' is a foreign word". MPR News. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Kanekar, Amar; Sharma, Manoj; Atri, Ashutosh (2010). "Enhancing Social Support, Hardiness, and Acculturation to Improve Mental Health among Asian Indian International Students". International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 30 (1): 55–68. doi:10.2190/iq.30.1.e. PMID 20353927. S2CID 207317013.

- ^ "higher internalizing symptoms: Topics by WorldWideScience.org". worldwidescience.org. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Health, Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental. "International Student Mental Health - Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental Health". Centre for Innovation in Campus Mental Health. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Hyun, Jenny; Quinn, Brian; Madon, Temina; Lustig, Steve (September 2007). "Mental health need, awareness, and use of counseling services among international graduate students". Journal of American College Health. 56 (2): 109–118. doi:10.3200/JACH.56.2.109-118. ISSN 0744-8481. PMID 17967756. S2CID 45512505.

- ^ a b Wei, Meifen; Liang, Ya-Shu; Du, Yi; Botello, Raquel; Li, Chun-I (2015). "Moderating effects of perceived language discrimination on mental health outcomes among Chinese international students". Asian American Journal of Psychology. 6 (3): 213–222. doi:10.1037/aap0000021.

- ^ a b Lin, Chenyang; Tong, Yuxin; Bai, Yaying; Zhao, Zixi; Quan, Wenxiang; Liu, Zhaorui; Wang, Jiuju; Song, Yanping; Tian, Ju; Dong, Wentian (14 April 2022). "Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Chinese international students in US colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study". PLOS ONE. 17 (4): e0267081. Bibcode:2022PLoSO..1767081L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267081. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 9009639. PMID 35421199.

- ^ Scott, Colin; Safdar, Saba; Desai Trilokekar, Roopa; El Masri, Amira (2015). "International Students as 'Ideal Immigrants' in Canada: A disconnect between policy makers' assumptions and the lived experiences of international students". Comparative and International Education. 43 (3). doi:10.5206/cie-eci.v43i3.9261. S2CID 54941911.

- ^ Bradley, Loretta; Parr, Gerald; Lan, William Y.; Bingi, Revathi; Gould, L. J. (1 March 1995). "Counselling expectations of international students". International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling. 18 (1): 21–31. doi:10.1007/BF01409601. ISSN 0165-0653. S2CID 145160218.

- ^ Sandhu, Daya Singh; Asrabadi, Badiolah Rostami (April 1991). "An Assessment of Psychological Needs of International Students: Implications for Counseling and Psychotherapy". Eric.

- ^ Jacob, Elizabeth J.; Greggo, John W. (1 January 2001). "Using Counselor Training and Collaborative Programming Strategies in Working With International Students". Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 29 (1): 73–88. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2001.tb00504.x. ISSN 2161-1912.

- ^ Yeh, Christine J.; Inose, Mayuko (2003). "International students' reported English fluency, social support satisfaction, and social connectedness as predictors of acculturative stress". Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 16: 15–28. doi:10.1080/0951507031000114058. S2CID 144614795.

- ^ Shadowen, Noel L.; Williamson, Ariel A.; Guerra, Nancy G.; Ammigan, Ravichandran; Drexler, Matthew L. (11 January 2019). "Prevalence and Correlates of Depressive Symptoms Among International Students: Implications for University Support Offices". Journal of International Students. 9 (1): 129–149. doi:10.32674/jis.v9i1.277. ISSN 2166-3750. S2CID 150370895.

- ^ Wu, Hsiao-ping; Garza, Esther; Guzman, Norma (2015). "International Student's Challenge and Adjustment to College". Education Research International. 2015: 1–9. doi:10.1155/2015/202753. ISSN 2090-4002.

- ^ Liu, Meirong (19 March 2009). "Addressing the Mental Health Problems of Chinese International College Students in the United States". Advances in Social Work. 10 (1): 69–86. doi:10.18060/164. ISSN 2331-4125.

- ^ "Students Should Study Abroad". BBC News. 20 April 2000. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Trends in U.S. Study Abroad". NAFSA: Association of International Educators. Archived from the original on 19 December 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ "The Condition of Education 2012". National Center for Education Statistics. 2012.

- ^ a b Velliaris, Donna M.; Coleman-George, Deb (eds.). Handbook of Research on Study Abroad Programs and Outbound Mobility. p. 280.

- ^ McGrath, Simon; Gu, Qing (eds.). Routledge Handbook of International Education and Development. p. 360.

- ^ Sowa, Patience A. (1 March 2002). "How valuable are student exchange programs?". New Directions for Higher Education. 2002 (117): 63–70. doi:10.1002/he.49. ISSN 1536-0741.

- ^ Gardner, Philip; Steglitz, Inge; Gross, Linda (2009). "Translating Study Abroad Experiences for Workplace Competencies". Peer Review. 11 (4): 19–22.

- ^ Chance, Patti L. (2009). Introduction to Educational Leadership and Organizational Behavior: Theory Into Practice. Rowman & Littlefield Education. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-59667-101-0.

- ^ a b Cushner, Kenneth (2009). "U.S Classroom Culture". NAFSA.

- ^ Priestley, Mark; Biesta, Gert; Robinson, Sarah (22 October 2015). Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 28. ISBN 978-1-4725-2587-1.