Anti-Slavic sentiment

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

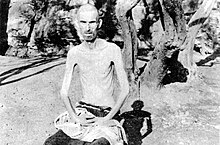

Anti-Slavism, also known as Slavophobia, a form of xenophobia, refers to various negative attitudes towards Slavic peoples, the most common manifestation is the claim that the inhabitants of Slavic nations are inferior to other ethnic groups, most notably Germanic peoples and Italian people. Slavophilia, by contrast, is a sentiment that celebrates Slavonic cultures or peoples and it has sometimes included a supremacist or nationalist tone. Anti-Slavism reached its highest peak during World War II, when Nazi Germany declared Slavs, especially neighboring Poles and Russians to be subhuman and planned to exterminate the majority of Slavic people.[1]

20th century

Albania

At the beginning of the 20th century, anti-Slavism developed in Albania by the work of the Franciscan friars who had studied in monasteries in Austria-Hungary,[2] after the recent massacres and expulsions of Albanians by their Slavic neighbours.[3] The Albanian intelligentsia proudly asserted, "We Albanians are the original and autochthonous race of the Balkans. The Slavs are conquerors and immigrants who came but yesterday from Asia".[4] In Soviet historiography, anti-Slavism in Albania was inspired by the Catholic clergy, which opposed the Slavic people because of the role the Catholic clergy played in preparations "for Italian aggression against Albania" and Slavs opposed "rapacious plans of Austro-Hungarian imperialism in Albania".[5]

Fascism and Nazism

Anti-Slavism was a notable component of Italian Fascism and Nazism both prior to and during World War II.

In the 1920s, Italian fascists targeted Yugoslavs, especially Serbs. They accused Serbs of having "atavistic impulses" and they also claimed that the Yugoslavs were conspiring together on behalf of "Grand Orient masonry and its funds". One anti-Semitic claim was that Serbs were part of a "social-democratic, masonic Jewish internationalist plot".[6]

Benito Mussolini viewed the Slavic race as inferior and barbaric.[7] He identified the Yugoslavs (Croats) as a threat to Italy and he viewed them as competitors over the region of Dalmatia, which was claimed by Italy, and he claimed that the threat rallied Italians together at the end of World War I: "The danger of seeing the Jugo-Slavians settle along the whole Adriatic shore had caused a bringing together in Rome of the cream of our unhappy regions. Students, professors, workmen, citizens—representative men—were entreating the ministers and the professional politicians".[8] These claims often tended to emphasize the "foreignness" of the Yugoslavs as newcomers to the area, unlike the ancient Italians, whose territories the Slavs occupied.

Nazi Germany

Anti-Slavic racism was an essential component of Nazism.[9] Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party regarded Slavic countries (especially Poland, the Soviet Union, and Yugoslavia) and their peoples as non-Aryan Untermenschen (subhumans), they were deemed to be foreign nations that could not be considered part of the Aryan master race.[1] Hitler in Mein Kampf stated: “One ought to cast the utmost doubt on the state-building power of the Slavs” and from beginning rejected the idea of incorporating Slavs within Greater Germany[10] There were exceptions for some minorities in these states which were deemed by the Nazis to be the descendants of ethnic German settlers and not Slavs who were willing to be Germanized.[9] Hitler considered the Slavs to be inferior, because the Bolshevik Revolution had put the Jews in power over the mass of Slavs, who were, by his own definition, incapable of ruling themselves but were instead being ruled by Jewish masters.[11] He considered the development of Modern Russia to have been the work of Germanic, not Slavic, elements in the nation, but believed those achievements had been undone and destroyed by the October Revolution.[12]

Because, according to the Nazis, the German people needed more territory to sustain its surplus population, an ideology of conquest and depopulation was formulated for Central and Eastern Europe according to the principle of Lebensraum, itself based on an older theme in German nationalism which maintained that Germany had a "natural yearning" to expand its borders eastward (Drang Nach Osten).[9] The Nazis' policy towards Slavs was to exterminate or enslave the vast majority of the Slavic population and repopulate their lands with millions of ethnic Germans and other Germanic peoples.[13][14] According to the resulting genocidal Generalplan Ost, millions of German and other "Germanic" settlers would be moved into the conquered territories, and the original Slavic inhabitants were to be annihilated, removed or enslaved.[9] The policy was focused especially towards the Soviet Union, as it alone was deemed capable of providing enough territory to accomplish this goal.[15] As part of this policy, the Hunger Plan was developed, which included seizing food produced on the occupied Soviet territory and delivering it primarily to German army. This should ultimately result in the starvation and death of 20 to 30 million people (mainly Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians). It is estimated that in 1941–1944 over four million Soviet citizens were starved according to this plan.[16] The resettlement policy reached a much more advanced state in Occupied Poland because of its immediate proximity to Germany.[9]

To deviate from ideological theories for strategic reasons by forging alliances with Independent State of Croatia (created after the invasion of Yugoslavia), and Bulgaria, puppet regime described the Croats officially as being "more Germanic than Slav", a notion made by Croatia's fascist dictator Ante Pavelić who imposed the view that the "Croatians were the descendants of the ancient Goths" who "had the Panslav idea forced upon them as something artificial".[17][18] However the Nazi regime continued to classify the Croats as "subhumans" despite its alliance with them.[19] Hitler also deemed the Bulgarians to be "Turkoman" in origin.[18]

See also

- Anti-Russian sentiment

- Anti-Polish sentiment

- Anti-Serbian sentiment

- Anti-Croatian sentiment

- Anti-Ukrainian sentiment

- Final Solution of the Czech Question

- Zamość Uprising

- Pan-Slavism

References

Notes

- ^ a b Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- ^ Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (2005), Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: convergence vs divergence, Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang S.A., p. 220, ISBN 90-5201-297-0,

it led to adoption of anti-Slavic component

- ^ Koliqi, Ernesto; Rahmani, Nazmi (2003). Vepra. Shtëpía Botuese Faik Konica. p. 183.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Kolarz, Walter (1972), Myths and realities in eastern Europe, Kennikat Press, p. 227, ISBN 978-0-8046-1600-3,

Albanian intelligentsia, despite the backwardness of their country and culture: 'We Albanians are the original and autochthonous race of the Balkans. The Slavs are conquerors and immigrants who came but yesterday from Asia.'

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|nopp=and|chapterurl=(help) - ^ Elsie, Robert. "Gjergj Fishta, The Voice of The Albanian Nation". Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

Great Soviet Encyclopaedia of Moscow... (March 1950): "The literary activities of the Catholic priest Gjergj Fishta reflect the role played by the Catholic clergy in preparing for Italian aggression against Albania. As a former agent of Austro-Hungarian imperialism, Fishta... took a position against the Slavic peoples who opposed the rapacious plans of Austro-Hungarian imperialism in Albania. In his chauvinistic, anti-Slavic poem 'The highland lute,' this spy extolled the hostility of the Albanians towards the Slavic peoples, calling for an open fight against the Slavs".

- ^ Burgwyn, H. James (1997) Italian Foreign Policy in the Interwar Period, 1918-1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. p.43.

- ^ Sestani, Armando, ed. (10 February 2012). "Il confine orientale: una terra, molti esodi" [The Eastern Border: One Land, Multiple Exoduses]. I profugi istriani, dalmati e fiumani a Lucca [The Istrian, Dalmatian and Rijeka Refugees in Lucca] (PDF) (in Italian). Instituto storico della Resistenca e dell'Età Contemporanea in Provincia di Lucca. pp. 12–13.

When dealing with such a race as Slavic - inferior and barbarian - we must not pursue the carrot, but the stick policy. We should not be afraid of new victims. The Italian border should run across the Brenner Pass, Monte Nevoso and the Dinaric Alps. I would say we can easily sacrifice 500,000 barbaric Slavs for 50,000 Italians.

- ^ Mussolini, Benito; Child, Richard Washburn; Ascoli, Max; & Lamb, Richard (1988) My rise and fall. New York: Da Capo Press. pp.105-106.

- ^ a b c d e Bendersky, Joseph W. (2007).A concise history of Nazi Germany Plymouth, U.K.: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 161-2

- ^ A Ridiculous Hundred Million Slavs: Concerning Adolf Hitler's World-view Jerzy Wojciech Borejsza, page 41, Wydawnictwo Neriton and Instytut Historii Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 2006

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P. (2007). War of Annihilation: Combat And Genocide on the Eastern Front, 1941. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-0-7425-4482-6.

- ^ Bendersky, Joseph W. (2000) A History of Nazi Germany: 1919-1945. Plymouth, UK: Rowman & Littlefield. p.177.

- ^ Housden, Martyn (2000). Hitler: Study of a Revolutionary?. Taylor & Francis. pp. 138–. ISBN 978-0-415-16359-0.

- ^ Perrson, Hans-Åke; Stråth, Bo (2007). Reflections on Europe: Defining a Political Order in Time and Space. Peter Lang. pp. 336–. ISBN 978-90-5201-065-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|last-author-amp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Hitler, Adolf (1926). Mein Kampf, Chapter XIV: Eastern Orientation or Eastern Policy. Quote: "If we speak of soil [to be conquered for German settlement] in Europe today, we can primarily have in mind only Russia and her vassal border states."

- ^ Snyder, Timothy (2010) Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. New York: Basic Books. p.411.

- ^ Rich, Norman (1974) Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p.276-7.

- ^ a b Hitler, Adolf and Gerhard, Weinberg (2007). Hitler's Table Talk, 1941-1944: His Private Conversations. Enigma Books. p.356. Quoting Hitler: "For example to label the Bulgarians as Slavs is pure nonsense; originally they were Turkomans."

- ^ Davies, Norman (2008) Europe at War 1939–1945: No Simple Victory. Pan Macmillan. pp.167,209.

Further reading

- Borejsza, Jerzy W. (1988). Antyslawizm Adolfa Hitlera. Warszawa: Czytelnik. ISBN 9788307017259.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Borejsza, Jerzy W. (1989). "Racisme et antislavisme chez Hitler". La politique nazie d'extermination. Paris: Albin Michel. pp. 57–74. ISBN 9782226038753.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Connelly, John (1999). "Nazis and Slavs: From Racial Theory to Racist Practice". Central European History. 32 (1): 1–33. doi:10.1017/s0008938900020628. PMID 20077627.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Connelly, John (2010). "Gypsies, Homosexuals, and Slavs". The Oxford Handbook of Holocaust Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 274–289. ISBN 9780199211869.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ersch, Johann Samuel, ed. (1810). "Erdbeschreibung". Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung. 2 (177). Halle-Leipzig: 465–472.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fagard, Michel (1977). L'antislavisme allemand a travers les publications specialisees des annees 1914 a 1921. Thèse de doctorat. Paris: Université de Paris VIII.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ferrari-Zumbini, Massimo (1994). "Grosse Migration und Antislawismus: Negative Ostjudenbilder im Kaiserreich". Jahrbuch für Antisemitismusforschung. 3: 194–226.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hund, Wulf D.; Koller, Christian; Zimmermann, Moshe, eds. (2011). Racisms Made in Germany. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643901255.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jaworska, Sylvia (2011). "Anti-Slavic imagery in German radical nationalist discourse at the turn of the twentieth century: A prelude to Nazi ideology?" (PDF). Patterns of Prejudice. 45 (5): 435–452. doi:10.1080/0031322x.2011.624762. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-10-22. Retrieved 2018-02-19.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leiberich, Michel (1977). L'antislavisme allemand dans la vie politique et quotidienne du kulturkapampf à la veille de la première guerre mondiale. Thèse de doctorat. Paris: Université de Paris VIII.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Libretti, Giovanni (1998). "The Presumed Antislavism of Engels". Beiträge zur Marx-Engels-Forschung: 191–202.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Promitzer, Christian (2003). "The South Slavs in the Austrian Imagination: Serbs and Slovenes in the Changing View from German Nationalism to National Socialism". Creating the Other: Ethnic Conflict & Nationalism in Habsburg Central Europe. New York: Berghahn Books. pp. 183–215. ISBN 9781782388524.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rash, Felicity (2012). German Images of the Self and the Other: Nationalist, Colonialist and Anti-Semitic Discourse 1871-1918. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230282650.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Serrier, Thomas (2004). "Antislavisme et antisémitisme dans les confins orientaux de l'Allemagne au XIXe siècle". Normes culturelles et construction de la déviance. Paris: École pratique des hautes études. pp. 91–102. ISBN 9782952156301.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wingfield, Nancy M., ed. (2003). Creating the Other: Ethnic Conflict & Nationalism in Habsburg Central Europe. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781782388524.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Wollman, Frank (1968). Slavismy a antislavismy za jara národů. Praha: Academia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)