Assassination of Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira

A Dassault Falcon 50 similar to the one involved in the shootdown. | |

| Assassination | |

|---|---|

| Date | 6 April 1994 |

| Summary | Shootdown |

| Site | Presidential Palace gardens, Kigali |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Dassault Falcon 50 |

| Registration | 9XR-NN |

| Flight origin | Dar es Salaam International Airport, Tanzania |

| Stopover | Kigali International Airport, Rwanda |

| Destination | Bujumbura International Airport, Burundi |

| Passengers | 9 |

| Crew | 3 |

| Fatalities | 12 |

| Survivors | 0 |

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Rwandan genocide |

|---|

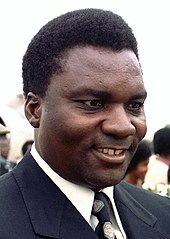

The assassination of Juvénal Habyarimana and Cyprien Ntaryamira on the evening of 6 April 1994 was the catalyst for the Rwandan Genocide. The airplane carrying Rwandan president Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down as it prepared to land in Kigali, Rwanda. The assassination set in motion some of the bloodiest events of the late 20th century, the Rwandan Genocide and the First Congo War. Responsibility for the attack is disputed, with most theories proposing as suspects either the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) or government-aligned Hutu Power extremists opposed to negotiation with the RPF. Regardless of the cause of the assassination, it unquestionably resulted in the immediate national mobilization of anti-Tutsi militias, the Interahamwe, who proceeded to set up roadblocks across Rwanda and slaughter every Tutsi or moderate Hutu until driven away by rebel RPF troops.

Background and prelude

In 1990, the Rwandan Civil War began when the Rwandan Patriotic Front, dominated by the Tutsi ethnic group, invaded northern Rwanda from Uganda. Most of the RPF fighters were either refugees or the sons of refugees who had fled ethnic purges by the Hutu government in the middle of the century. The attempt to overthrow the government failed, though the RPF was able to maintain control of a border region.[1] As it became clear that the war had reached a stalemate, the sides began peace negotiations in May 1992, which resulted in the signing in August 1993 of the Arusha Accords to create a power-sharing government.[2]

However, the war radicalized the internal opposition. The RPF's show of force intensified support for the so-called "Hutu Power" ideology. Hutu Power portrayed the RPF as an alien force intent on reinstating the Tutsi monarchy and enslaving the Hutus: a prospect which must be resisted at all costs.[3] This ideology was embraced most wholeheartedly by the Coalition for the Defense of the Republic (CDR) who advocated racist principles known as the Hutu Ten Commandments. This political force led to the collapse of the first Habyarimana government in July 1993, when Prime Minister Dismas Nsengiyaremye criticized the president in writing for delaying a peace agreement. Habyarimana, a member of the MRND political party, dismissed Nsengiyarmye and appointed Agathe Uwilingiyimana, who was perceived to be less sympathetic to the RPF, in his stead. However, the main opposition parties refused to support Madame Agathe's appointment, each splitting into two factions: one calling for the unwavering defense of Hutu Power and the other, labeled "moderate", that sought a negotiated settlement to the war. As Prime Minister Uwilingiyimana was unable to form a coalition government, ratification of the Arusha Accords was impossible. The most extreme of the Hutu parties, the CDR, which openly called for ethnic cleansing of the Tutsi, was entirely unrepresented in the Accords.[4]

The security situation deteriorated throughout 1993. Armed Hutu militias attacked Tutsis throughout the country, while high-ranking adherents of Hutu Power began to consider how the security forces might be turned to genocide.[5] In February 1994, Roméo Dallaire, the head of the military force attached to the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), which had been sent to observe the implementation of the Arusha Accords, informed his superiors, "Time does seem to be running out for political discussions, as any spark on the security side could have catastrophic consequences."[6]

In the United Nations Security Council, early April 1994 saw a sharp disagreement between the United States and the non-permanent members of the council over UNAMIR. Despite a classified February Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) analysis predicting half a million deaths if the Arusha process failed,[7] the U.S. was attempting to reduce its international commitments in the wake of the Somalia debacle and lobbied to end the mission. A compromise extending UNAMIR's mandate for three more months was finally reached on the evening of Tuesday, the fifth of April. Meanwhile, Habyarimana was finishing regional travel. On April 4, he had flown to Zaire to meet with president Mobutu Sese Seko and on the sixth flew to Dar es Salaam, Tanzania for a one-day regional summit for heads of state convened by Tanzania's President.[8] On the return trip that evening he was joined by Burundian president Cyprien Ntaryamira, and a couple of his ministers, who preferred the faster Dassault Falcon 50 that the French government had given to Habyarimana over Ntaryamira's own presidential plane.[9]

According to interim Prime Minister Jean Kambanda's testimony to the ICTR, President Mobutu Sese Seko of neighboring Zaire (now DRC) had warned Habyarimana not to go to Dar es Salaam on April 6. Mobutu reportedly said this warning had come from a very senior official in the Elysée Palace in Paris. There was a link between this warning, said Mobutu, and the subsequent suicide in the Elysée of François de Grossouvre, a senior high-ranking official working for President François Mitterrand, an official who had killed himself on April 7 after learning about the downing of the Falcon.[10]

Description of attack

Shortly before 8:20 pm local time (18:20 UTC), the presidential jet circled once around Kigali International Airport before coming in for final approach in clear skies.[11] A weekly flight by a Belgian C-130 Hercules carrying UNAMIR troops returning from leave had been scheduled to land before the presidential jet, but was waved off to give the president priority.[12]

A surface-to-air missile struck one of the wings of the Dassault Falcon, then a second missile hit its tail. The plane erupted into flames in mid-air before crashing into the garden of the presidential palace, exploding on impact.[11] The plane carried three French crew and nine passengers.[13]

The attack was witnessed by numerous people. One of two Belgian officers in the garden of a house in Kanombe, the district in which the airport is located, saw and heard the first missile climb into the sky, saw a red flash in the sky and heard an aircraft engine stopping, followed by another missile. He immediately called Major de Saint-Quentin, part of the French team attached to the Rwandan para-commando battalion Commandos de recherche et d'action en profondeur, who advised him to organize protection for his Belgian comrades. Similarly, another Belgian officer stationed in an unused airport control tower saw the lights of an approaching aircraft, a light traveling upward from the ground and the aircraft lights going out. This was followed by a second light rising from the same place as the first and the plane turning into a falling ball of fire. This officer immediately radioed his company commander, who confirmed with the operational control tower that the plane was the presidential aircraft.[14]

A Rwandan soldier in the military camp in Kanombe recalled,

You know, its engine sound was different from other planes; that is, the president's engine's sound ... We were looking towards where the plane was coming from, and we saw a projectile and we saw a ball of flame or flash and we saw the plane go down; and I saw it. I was the leader of the bloc so I asked the soldiers to get up and I told them "Get up because Kinani [a Kinyarwanda nickname for Habyarimana meaning "famous" or "invincible"] has been shot down.' They told me, "You are lying." I said, "It's true." So I opened my wardrobe, I put on my uniform and I heard the bugle sound.[15]

A Rwandan officer cadet at the airport who was listening to the Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines heard the announcer state that the presidential jet was coming in to land. The spoken broadcast stopped suddenly in favor of a selection of classical music.[16]

People killed

All twelve aboard the Falcon were killed. They were:[17][18]

|

French aircraft crew:

|

Immediate reaction

Chaos ensued on the ground. The Presidential Guard, who had been waiting to escort the president home from the airport, threatened people with their weapons. Twenty Belgian peacekeepers who had been stationed along the perimeter of the airport were surrounded by the Presidential Guard and some were disarmed.[16] The airport was closed and the circling Belgian Hercules was diverted to Nairobi.[12]

In Camp Kanombe, the bugle call immediately after the crash was taken by soldiers to mean that the Rwandan Patriotic Front had attacked the camp. The soldiers rushed to their units' armories to equip themselves. Soldiers of the paracommando brigade Commandos de recherche et d'action en profondeur assembled on the parade ground at around 9 pm while members of other units gathered elsewhere in the camp.[19] At least one witness stated that about an hour after the crash there was the sound of gunfire in Kanombe. Munitions explosions at Camp Kanombe were also initially reported.[16]

The senior officer for the Kigali operational zone called the Ministry of Defence with the news. Defence Minister Augustin Bizimana was out of the country, and the officer who took the call failed to reach Col. Théoneste Bagosora, the director of the office of the minister of defence, who was apparently at a reception given by UNAMIR's Bangladeshi officers.[16]

The news of the crash, initially reported as an explosion of UNAMIR's ammunition dump, was quickly relayed to UNAMIR Force Commander Dallaire. He ordered UNAMIR Kigali sector commander Luc Marchal to send a patrol to the crash site.[20] Numerous people began calling UNAMIR seeking information, including Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and Lando Ndasingwa. Uwilingiyimana informed Dallaire that she was trying to gather her cabinet but many ministers were afraid to leave their families. She also reported that all of the hardline ministers had disappeared. Dallaire asked the prime minister if she could confirm that it was the president's plane that had crashed, and called UNAMIR political head Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh to inform him of developments. Uwilingiyimana called back to confirm that it was the president's jet and he was presumed to be on board. She also asked for UNAMIR help in regaining control of the political situation, as she was legally next in the line of succession, but some moderate ministers allied to her had already begun fleeing their homes, fearing for their safety.[21]

At 9:18 pm, Presidential Guards whom a UNAMIR report described as "nervous and dangerous" established a roadblock near the Hotel Méridien. Several other roadblocks had been set up prior to the attack as part of security preparations for Habyarimana's arrival.[22] The patrol of UNAMIR Belgian soldiers sent to investigate the crash site was stopped at a Presidential Guards roadblock at 9:35 pm, disarmed and sent to the airport.[15]

The para-commando brigade CRAP was ordered to collect bodies from the crash site and UN peacekeepers were prevented from accessing the site.[23] Later, two French soldiers arrived at the crash and asked to be given the flight data recorder once it was recovered.[19] The whereabouts of the flight data recorder were later unknown. French military contacted Dallaire and offered to investigate the crash, which Dallaire refused immediately.[23]

A Rwandan colonel who called the army command about 40 minutes after the crash was told that there was no confirmation that the president was dead. About half an hour later, roughly 9:30, the situation was still confused at army command, though it appeared clear that the presidential aircraft had exploded and that it had probably been hit by a missile. News arrived that Major-General Déogratias Nsabimana, the army chief of staff, had been on the plane. The officers present realized that they would have to appoint a new chief of staff in order to clarify the chain of command and began a meeting to decide whom to appoint. Col. Bagosora joined them soon afterward.[24] At about 10 pm, Ephrem Rwabalinda, the government liaison officer to UNAMIR, called Dallaire to inform him that a crisis committee was about to meet. After informing his superiors in New York City of the situation, Dallaire went to attend the meeting, where he found Bagosora in charge.[25]

- For subsequent events, see Initial events of the Rwandan Genocide.

Long-term events

The death toll of the Rwandan Genocide is commonly estimated at 800,000, though some estimates top one million. The RPF invaded, eventually capturing the country and installing a new government. About 1.2 million refugees fled to neighboring countries, partially due to fear of RPF retribution and partially due to a plan by the Hutu extremists to use the refugee camps as military bases for the reconquest of Rwanda. The Great Lakes refugee crisis thus became increasingly politicized and militarized until the RPF supported a rebel attack against the refugee camps across the border in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1996. The rebel Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo continued their offensive, in the First Congo War, until they overthrew the government of Mobutu Sese Seko. In 1998, the new Congolese president, Laurent-Désiré Kabila, had a falling out with his foreign backers, who began another rebellion to put a more amenable government into place. The resulting Second Congo War (1998–2003) drew in eight nations and became the deadliest conflict since World War II, killing an estimated 3.8 million people.[citation needed]

The Burundi Civil War continued after the death of Ntaryamira, both being sustained by and feeding into the instability in Rwanda and the Congo. Over 300,000 people died before a government of national unity was established in 2005.[citation needed]

At some point following the April 6 assassination, Juvenal Habyarimana's remains were obtained by Zairian President Mobutu Sese Seko and stored in a private mausoleum in Gbadolite, Zaire (now Democratic Republic of the Congo). Mobutu promised Habyarimana's family that his body would eventually be given a proper burial in Rwanda. On May 12, 1997, as Laurent-Désiré Kabila's ADFL rebels were advancing on Gbadolite, Mobutu had the remains flown by cargo plane to Kinshasa where they waited on the tarmac of N'djili Airport for three days. On May 16, the day before Mobutu fled Zaire, Habyarimana's remains were burned under the supervision of an Indian Hindu leader.[26]

Responsibility

While initial suspicion fell upon the Hutu extremists who carried out the subsequent genocide, there have been several reports since 2000 stating that the attack was carried out by the RPF on the orders of Paul Kagame, who went on to become president of Rwanda. However, all such evidence is heavily disputed and many academics, as well as the United Nations, have refrained from issuing a definitive finding. Mark Doyle, a BBC News correspondent who reported out of Kigali through the 1994 genocide, noted in 2006 that the identities of the assassins "could turn out to be one of the great mysteries of the late 20th Century".[27] Paul Kagame and the RPF's accusation of Hutu extremists shooting down the plane has received state support, and suppression of accusations of RPF involvement. Belgium has refrained from supporting either position.

A now-declassified U.S. State Department intelligence report from 7 April reports an unidentified source telling the U.S. ambassador in Rwanda "rogue Hutu elements of the military—possibly the elite presidential guard—were responsible for shooting down the plane."[28] This conclusion was supported by other U.S. agencies, including the CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency.[29] Philip Gourevitch, in his bestselling 1998 book on the genocide, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, framed the thinking of the time:

Although Habyarimana's assassins have never been positively identified, suspicion has focused on the extremists in his entourage—notably the semiretired Colonel Théoneste Bagosora, an intimate of Madame Habyarimana, and a charter member of the akazu and its death squads, who said in January 1993 that he was preparing an apocalypse.[30]

The 1997 report of the Belgian Senate stated that there was not enough information to determine specifics about the assassination.[31] A 1998 report by the National Assembly of France posited two probable explanations. One is that the attack was carried out by groups of Hutu extremists, distressed by the advancement of negotiations with the RPF, the political and military adversary of the current regime, while the other is that it was the responsibility of the RPF, frustrated at the lack of progress in the Arusha Accords. Among the other hypotheses that were examined is one that implicates the French military, although there is no clear motive for a French attack on the Rwandan government. The 1998 French report made no determination between the two dominant theories.[17] A 2000 report by the Organisation of African Unity does not attempt to determine responsibility.[32]

A January 2000 article in the Canadian National Post reported that International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda prosecutor Louise Arbour had suppressed a report detailing accusations by three Tutsi informants that the RPF under Kagame had carried out the assassination with the help of a foreign government.[33] The UN later clarified that the 'report' was actually a three-page memorandum by investigator Michael Hourigan of Australia, who had been unsure of the credibility of the information and simply filed it into archives. The UN sent the memo on to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, where defense attorneys had expressed interest in using it on behalf of their clients.[34][35]

In 2004, a report by French anti-terrorist magistrate Jean-Louis Bruguière, investigating the deaths of the French aircraft crew, stated that the assassination had been carried out on the orders of Paul Kagame. The report relies heavily on the testimony of Abdul Ruzibiza, a former lieutenant in the RPF, who states that he was part of a cell that carried out the assassination with shoulder-fired SA-16 missiles.[18][36] Ruzibaza later published his testimony in a press release, detailing his account and further accusing the RPF of starting the conflict, prolonging the genocide, carrying out widespread atrocities during the genocide and political repression.[37] The former RPF officer went on to publish a 2005 book Rwanda. L’histoire secrete with his account.[38] Bruguière reportedly claims that the CIA was involved in Habyarimana's assassination.[39]

Paul Rusesabagina, a Rwandan of mixed Hutu and Tutsi origin whose life-saving efforts was the basis of the 2004 film Hotel Rwanda, has supported the allegation that Kagame and the RPF were behind the plane downing, and wrote in November 2006:[40]

It defies logic why the UN Security Council has never mandated an investigation of this airplane missile attack to establish who was responsible, especially since everyone agrees it was the one incident that touched off the mass killings commonly referred to as the "Rwandan genocide of 1994".

Also in November 2006, Bruguière issued another report accusing Kagame and the RPF of masterminding the assassination. In protest, Kagame broke diplomatic relations between France and Rwanda. Linda Melvern, author of Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide, noted

the evidence the French judge had presented alleging President Kagame's involvement in the murder of his predecessor was very sparse, and that some of it, concerning the alleged anti-aircraft missiles used to down the presidential jet, had already been rejected by a French Parliamentary enquiry.[27]

Kagame also ordered the formation of a commission of Rwandans that was "charged with assembling proof of the involvement of France in the genocide".[41] The political character of that investigation was further averred when the commission issued its report solely to Kagame in November 2007 and its head, Jean de Dieu Mucyo, stated that the commission would now "wait for President Kagame to declare whether the inquiry was valid".[41]

A 2007 article by Colette Braeckman in Le Monde Diplomatique strongly questions the reliability of Judge Bruguière's report and suggests the direct involvement of French military personnel acting for or with the Presidential Guard of the Rwanda governmental forces in the missile attack on the aircraft.[42] In a 2007 interview with the BBC, Kagame said he would co-operate with an impartial inquiry. The BBC concluded, "Whether any judge would want to take on such a task is quite another matter."[43]

Bruguière also issued arrest warrants for nine Kagame aides, in order to question them about the assassination. In November 2008 the German government implemented the first of these European warrants and arrested Rose Kabuye, Kagame's chief of protocol, upon her arrival in Frankfurt. Kabuye apparently agreed to be transferred to French custody immediately in order to respond to Bruguière's questions.[44] Later scrutiny into the Brugiere report by the judge Marc Trévidic, revealed that much of it relied on testimony from RPF soldiers who later retracted their testimony.[23]

In January 2010, the Rwandan government released the "Report of the Investigation into the Causes and Circumstances of and Responsibility for the Attack of 06/04/1994 Against The Falcon 50 Rwandan Presidential Aeroplane Registration Number 9XR-NN," known as the Mutsinzi Report. The multivolume report implicates proponents of Hutu Power in the attack and Philip Gourevitch states, "two months ago, on the day after Rwanda's admission to the Commonwealth, France and Rwanda reestablished normal diplomatic relations. Before that happened, of course, the Rwandans had shared the about-to-be-released Mutsinzi report with the French. The normalization of relations amounts to France’s acceptance of the report's conclusions."[45][46]

Even the location from which the missiles were fired is disputed. Eyewitnesses have variously stated that they saw the missiles launched from Gasogi Hill, Nyandungu Valley, Rusororo Hill and Masaka Hill. Some witnesses claim to have seen used shoulder-launched missile launchers on Masaka Hill.[47]

A French investigation made public in January 2012 identified the Kanombe barracks as the likely source of the missile.[48][49] The base was controlled by FAR forces, including the Presidential Guard[23] and the para-commando battalion, and the AntiAircraft Battalion (LAA) were also based there.[50] This report was widely reported to exonerate the RPF,[48] although this was not in fact the case, according to Filip Reyntjens.[51]

Notes

- ^ Mamdani, p. 186

- ^ Melvern, pp. 36-37

- ^ Mamdani, pp. 189-191

- ^ Mamdani, pp. 211-212

- ^ Melvern, pp. 45-46

- ^ "Report of the Independent Inquiry into the Actions of the UN during the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda" Archived 2006-04-16 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations (hosted by ess.uwe.ac.uk). For the slow connection to the copy hosted by un.org, see here [1] Archived 2007-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Melvern, p. 128

- ^ Melvern, pp. 128-131

- ^ Melvern, p. 142

- ^ Melvern, Linda: "Expert Refutes Bruguière Claims that RPF Shot Down Rwandan President’s Aircraft in 1994." The New Times. November 27, 2006.

- ^ a b Melvern, p. 133

- ^ a b Dallaire & Beardsley, pp. 228

- ^ Criminal Occurrence description, Aviation Safety Network

- ^ Melvern, pp. 133-134

- ^ a b Melvern, p. 135

- ^ a b c d Melvern, p. 134

- ^ a b Report of the Information Mission on Rwanda, Section 4: L'Attentat du 6 Avril 1994 Contre L'Avion du Président Juvénal Habyarimana, 15 December 1998Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b "Report" (PDF). (1.01 MB) by Jean-Louis Bruguière, Paris Court of Serious Claims (Tribunal de Grande Instance), 17 November 2006, p. 1 (hosted by lexpress.fr) Template:Fr icon

- ^ a b Melvern, pp. 135-136

- ^ Dallaire & Beardsley, p. 221

- ^ Dallaire & Beardsley, pp. 221-222

- ^ Melvern, pp. 134-135

- ^ a b c d Melvern, Linda (10 January 2012). "Rwanda: at last we know the truth". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Melvern, p. 136

- ^ Dallaire & Beardsley, p. 222

- ^ "Ending a Chapter, Mobutu Cremates Rwanda Ally by Howard W. French. New York Times. May 16, 1997.

- ^ a b "Rwanda's mystery that won't go away" by Mark Doyle, BBC News, 29 November 2006

- ^ "Rwanda/Burundi: Turmoil in Rwanda" (PDF). (101 KB), U.S. Department of State's Spot Intelligence Report as of 08:45 EDT, 7 April 1994, hosted by "The U.S. and the Genocide in Rwanda 1994: The Assassination of the Presidents and the Beginning of the 'Apocalypse'" by William Ferroggiaro, National Security Archive, April 7, 2004

- ^ Pentagon/Rwanda genocide, , Voice of America broadcast on 30 April 1994 (transcript hosted by GlobalSecurity.org)

- ^ Philip Gourevitch, We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families, New York: Picador, ISBN 0-312-24335-9, p. 113

- ^ Report of the Commission d'enquête parlementaire concernant les événements du Rwanda, Section 3.5.1: L'attentat contre l'avion présidentiel, Belgian Senate session of 1997-1998, 6 December 1997 Template:Fr icon

- ^ Rwanda : le génocide qu'on aurait pu stopper, Chapter 14: The Genocide, by the Organisation of African Unity, 29 May 2000 Template:Fr icon

- ^ "Explosive Leak on Rwanda Genocide" by Steven Edwards, National Post, January 3, 2000 (hosted by geocities.com)

- ^ "Memo Links Rwandan Leader To Killing", BBC News, 29 March 2000

- ^ "Statement by the President of the ICTR: Plane crash in Rwanda in April 1994 (ICTR/INFO-9-2-228STA.EN)". Arusha: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. 7 April 2000.

- ^ "Rwanda Denies French Allegations", BBC News, 11 March 2004. For less critical coverage, see "Nobody Can Call It a 'Plane Crash' Now! Judge Bruguière's Report on the Assassination of former Rwandan President Habyarimana" by Robin Philpot, CounterPunch, 12/14 March 2004. For an RPF-responsibility theory pulling together multiple allegations and reports, see "Rwanda's Secret War" by Keith Harmon Snow, Global Policy Forum, 10 December 2004

- ^ Testimony of Abdul Ruzibiza Archived 2005-04-06 at the Wayback Machine, 14 March 2004 (hosted by fdlr.r-online.info)

- ^ "Kagame Ordered Shooting Down of Habyarimana's Plane-Ruzibiza" Archived 2007-10-11 at the Wayback Machine, Just World News, 14 November 2004

- ^ "Second Thoughts on the Hotel Rwanda: Boutros-Ghali: a CIA Role in the 1994 Assassination of Rwanda's President Habyarimana?" by Robin Philpot, Counterpunch, 26/27 February 2005

- ^ Rusesabagina, Paul (November 2006). "Compendium of RPF crimes - October 1990 to present: The case for overdue prosecution" (PDF). Retrieved 4 January 2010.

- ^ a b "Génocide rwandais: le rapport sur le rôle de la France remis à Paul Kagamé" (in French). AFP. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- ^ "Accusations suspectes contre le régime rwandais," Le Monde Diplomatique, January 2007 (retrieved 13 April 2009)Template:Fr icon

- ^ "Rwanda leader defiant on killing claim". BBC. 30 January 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ^ "Rwandan president's aide arrested in Germany". AFP. 10 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gourevitch, Philip (8 January 2010). "The Mutsinzi Report on the Rwandan Genocide". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 January 2010. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ See "Committee of Experts Investigation of the April 6, 1994 Crash of President Habyarimana's Dassault Falcon-50 Aircraft" (zipped file). January 2010.

- ^ Melvern, map 1

- ^ a b Epstein, Helen C. (12 September 2017). "America's secret role in the Rwandan genocide". The Guardian.

- ^ "French Judges release report on the plane crash used as a pretext to start genocide in Rwanda". Government of Rwanda. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

- ^ http://sweden.embassy.gov.rw/content/view/287/98/lang,english/

- ^ Reyntjens, Filip (21 October 2014). "Rwanda's Untold Story. A reply to "38 scholars, scientists, researchers, journalists and historians"". African Arguments.

References

- Dallaire, Roméo; Beardsley, Brent (2003). Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda. New York City: Carroll & Graf Publishers. ISBN 0-7867-1487-5.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (2001). When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-10280-5.

- Melvern, Linda (2004). Conspiracy to Genocide: The Rwandan Genocide. New York City: Verso. ISBN 0-312-30486-2.

External links

- Video Animation of the Crash - Synopsis of findings from Rwanda's Mutsinzi Report Government of Rwanda Media Guide to the Committee of Experts Investigation of the April 6, 1994 Crash of President Habyarimana's Dassault Falcon-50 Aircraft.

- 1994 in politics

- Mass murder in 1994

- 1994 crimes in Rwanda

- Rwandan genocide

- Assassinations in Rwanda

- 20th-century aircraft shootdown incidents

- Kigali

- Aviation accidents and incidents in Rwanda

- 1994 in international relations

- Aviation accidents and incidents involving state leaders

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1994

- Terrorist incidents in 1994

- Conspiracy theories involving aviation incidents

- April 1994 events