Caligula

| Caligula | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bust of Caligula at the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek museum in Copenhagen | |||||

| 3rd Emperor of the Roman Empire | |||||

| Reign | 37–41 AD | ||||

| Predecessor | Tiberius, great uncle | ||||

| Successor | Claudius, uncle | ||||

| Born | 31 August 12 AD Antium, Italy | ||||

| Died | 24 January 41 AD (aged 28) Palatine Hill, Rome | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Julio-Claudian dynasty | ||||

| Father | Germanicus | ||||

| Mother | Agrippina the Elder | ||||

| Religion | Roman Paganism | ||||

"Caligula" (/kəˈlɪɡjələ/; Template:Lang-la;[1]) was the popular nickname of Gaius (31 August 12 AD – 22 January 41 AD), Roman emperor from 37 AD to 41 AD. Caligula was a member of the house of rulers conventionally known as the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Caligula's father Germanicus, the nephew and adopted son of Emperor Tiberius, was a very successful general and one of Rome's most beloved public figures. The young Gaius earned the nickname Caligula (meaning "little soldier's boot", the diminutive form of caliga, hob-nailed military boot) from his father's soldiers while accompanying him during his campaigns in Germania.

When Germanicus died at Antioch in 19 AD, his wife Agrippina the Elder returned to Rome with her six children where she became entangled in an increasingly bitter feud with Tiberius. This conflict eventually led to the destruction of her family, with Caligula as the sole male survivor. Unscathed by the deadly intrigues, Caligula accepted the invitation to join the emperor on the island of Capri in 31 AD, where Tiberius himself had withdrawn five years earlier. With the death of Tiberius in 37 AD, Caligula succeeded his great uncle and adoptive grandfather.

There are few surviving sources on Caligula's reign, although he is described as a noble and moderate ruler during the first six months of his rule. After this, the sources focus upon his cruelty, sadism, extravagance, and intense sexual perversity, presenting him as an insane tyrant. While the reliability of these sources has increasingly been called into question, it is known that during his brief reign, Caligula worked to increase the unconstrained personal power of the emperor (as opposed to countervailing powers within the principate). He directed much of his attention to ambitious construction projects and notoriously luxurious dwellings for himself. However, he initiated the construction of two new aqueducts in Rome: the Aqua Claudia and the Anio Novus. During his reign, the Empire annexed the Kingdom of Mauretania and made it into a province.

In early 41 AD, Caligula became the first Roman emperor to be assassinated, the result of a conspiracy involving officers of the Praetorian Guard, as well as members of the Roman Senate and of the imperial court. The conspirators' attempt to use the opportunity to restore the Roman Republic was thwarted: on the same day the Praetorian Guard declared Caligula's uncle Claudius emperor in his place.

Early life

Family

| Roman imperial dynasties | ||

|---|---|---|

| Julio-Claudian dynasty | ||

| Chronology | ||

|

27 BC – AD 14 |

||

|

AD 14–37 |

||

|

AD 37–41 |

||

|

AD 41–54 |

||

|

AD 54–68 |

||

|

||

Caligula was born in Antium on 31 August 12 AD, the third of six surviving children born to Germanicus and Germanicus' second cousin Agrippina the Elder.[2] Gaius's brothers were Nero and Drusus.[2] His sisters were Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla, and Julia Livilla.[2] Gaius was nephew to Claudius (the future emperor).[3]

Agrippina the Elder was the daughter of Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa and Julia the Elder.[2] She was a granddaughter of Augustus and Scribonia.[2]

Youth and early career

As a boy of just two or three, Gaius accompanied his father, Germanicus, on campaigns in the north of Germania.[4] The soldiers were amused that Gaius was dressed in a miniature soldier's uniform, including boots and armor.[4] He was soon given his nickname Caligula, meaning "little (soldier's) boot" in Latin, after the small boots he wore as part of his uniform.[5] Gaius, though, reportedly grew to dislike this nickname.[6]

Suetonius claims that Germanicus was poisoned in Syria by an agent of Tiberius, who viewed Germanicus as a political rival.[7]

After the death of his father, Caligula lived with his mother until her relations with Tiberius deteriorated.[8] Tiberius would not allow Agrippina to remarry for fear her husband would be a rival.[9] Agrippina and Caligula's brother, Nero, were banished in 29 AD on charges of treason.[10][11]

The adolescent Caligula was then sent to live first with his great-grandmother (and Tiberius's mother) Livia.[8] Following Livia's death, he was sent to live with his grandmother Antonia.[8] In 30 AD, his brother, Drusus Caesar, was imprisoned on charges of treason and his brother Nero died in exile from either starvation or suicide.[11][12] Suetonius writes that after the banishment of his mother and brothers, Caligula and his sisters were nothing more than prisoners of Tiberius under the close watch of soldiers.[13]

In 31 AD, Caligula was remanded to the personal care of Tiberius on Capri, where he lived for six years.[8] To the surprise of many, Caligula was spared by Tiberius.[14] According to historians, Caligula was an excellent natural actor and, recognizing danger, hid all his resentment towards Tiberius.[8][15] An observer said of Caligula, "Never was there a better servant or a worse master!"[8][15]

After he became Emperor, Caligula claimed to have planned to kill Tiberius with a dagger in order to avenge his mother and brother: however, having brought the weapon into Tiberius's bedroom he did not kill the Emperor but instead threw the dagger down on the floor. Supposedly Tiberius knew of this but never dared to do anything about it.[16] Suetonius claims that Caligula was already cruel and vicious: he writes that, when Tiberius brought Caligula to Capri, his purpose was to allow Caligula to live in order that he "... prove the ruin of himself and of all men, and that he was rearing a viper for the Roman People and a Phaëton for the world."[17]

In 33 AD, Tiberius gave Caligula an honorary quaestorship, a position he held until his rise to Emperor.[18] Meanwhile, both Caligula's mother and his brother Drusus died in prison.[19][20] Caligula was briefly married to Junia Claudilla in 33, though she died during childbirth the following year.[21] Caligula spent time befriending the Praetorian Prefect, Naevius Sutorius Macro, an important ally.[21] Macro spoke well of Caligula to Tiberius, attempting to quell any ill will or suspicion the emperor felt towards Caligula.[22]

In 35 AD, Caligula was named joint heir to Tiberius's estate along with Tiberius Gemellus.[23]

Emperor

Early reign

When Tiberius died on 16 March 37 AD, his estate and the titles of the Principate were left to Caligula and Tiberius's own grandson, Gemellus, who were to serve as joint heirs. Although Tiberius was 78 and on his death bed, some ancient historians still conjecture that he was murdered.[21][24] Tacitus writes that the Praetorian Prefect, Macro, smothered Tiberius with a pillow to hasten Caligula's accession, much to the joy of the Roman people,[24] while Suetonius writes that Caligula may have carried out the killing, though this is not recorded by any other ancient historian.[21] Seneca the elder and Philo, who both wrote during Tiberius's reign, as well as Josephus record Tiberius as dying a natural death.[25] Backed by Macro, Caligula had Tiberius' will nullified with regards to Gemellus on grounds of insanity, but otherwise carried out Tiberius' wishes.[26]

Caligula accepted the powers of the Principate as conferred by the Senate and entered Rome on 28 March amid a crowd that hailed him as "our baby" and "our star," among other nicknames.[27] Caligula is described as the first emperor who was admired by everyone in "all the world, from the rising to the setting sun."[28] Caligula was loved by many for being the beloved son of the popular Germanicus,[27] and because he was not Tiberius.[29] It was said by Suetonius that over 160,000 animals were sacrificed during three months of public rejoicing to usher in the new reign.[30][31] Philo describes the first seven months of Caligula's reign as completely blissful.[32]

Caligula's first acts were said to be generous in spirit, though many were political in nature.[26] To gain support, he granted bonuses to those in the military including the Praetorian Guard, city troops and the army outside Italy.[26] He destroyed Tiberius's treason papers, declared that treason trials were a thing of the past, and recalled those who had been sent into exile.[33] He helped those who had been harmed by the Imperial tax system, banished certain sexual deviants, and put on lavish spectacles for the public, such as gladiator battles.[34][35] Caligula collected and brought back the bones of his mother and of his brothers and deposited their remains in the tomb of Augustus.[36]

In October 37 AD, Caligula fell seriously ill, or perhaps was poisoned. He recovered from his illness soon thereafter, but many believed that the young emperor had changed into a diabolical mind as he started to kill off or exile those who were close to him or whom he saw as a serious threat. Perhaps his illness reminded him of his mortality and of the desire of others to advance into his place.[37] He had his cousin and adopted son Tiberius Gemellus executed – an act that outraged Caligula's and Gemellus's mutual grandmother Antonia Minor. She is said to have committed suicide, although Suetonius hints that Caligula actually poisoned her. He had his father-in-law Marcus Junius Silanus and his brother-in-law Marcus Lepidus executed as well. His uncle Claudius was spared only because Caligula kept him as a laughing stock. His favorite sister Julia Drusilla died in 38 AD of a fever: his other two sisters, Livilla and Agrippina the Younger, were exiled. He hated the fact that he was the grandson of Agrippa, and slandered Augustus by repeating a falsehood that his mother was actually the result of an incestuous relationship between Augustus and his daughter Julia the Elder.[38]

Public reform

In AD 38, Caligula focused his attention on political and public reform. He published the accounts of public funds, which had not been made public during the reign of Tiberius. He aided those who lost property in fires, abolished certain taxes, and gave out prizes to the public at gymnastic events. He allowed new members into the equestrian and senatorial orders.[39]

Perhaps most significantly, he restored the practice of democratic elections.[40] Cassius Dio said that this act "though delighting the rabble, grieved the sensible, who stopped to reflect, that if the offices should fall once more into the hands of the many ... many disasters would result".[41]

During the same year, though, Caligula was criticized for executing people without full trials and for forcing his helper Macro to commit suicide.[42]

Financial crisis and famine

According to Cassius Dio, a financial crisis emerged in AD 39.[42] Suetonius places the beginning of this crisis in 38.[43] Caligula's political payments for support, generosity and extravagance had exhausted the state's treasury. Ancient historians state that Caligula began falsely accusing, fining and even killing individuals for the purpose of seizing their estates.[44]

A number of other desperate measures by Caligula are described by historians. In order to gain funds, Caligula asked the public to lend the state money.[45] Caligula levied taxes on lawsuits, marriage and prostitution.[46] Caligula began auctioning the lives of the gladiators at shows.[44][47] Wills that left items to Tiberius were reinterpreted to leave the items instead to Caligula.[48] Centurions who had acquired property during plundering were forced to turn over spoils to the state.[48]

The current and past highway commissioners were accused of incompetence and embezzlement and forced to repay money.[48] According to Suetonius, in the first year of Caligula's reign he squandered 2,700,000,000 sesterces that Tiberius had amassed.[49] His nephew Nero Caesar both envied and admired the fact that Gaius had run through the vast wealth Tiberius had left him in so short a time.[50]

A brief famine of unknown size occurred, perhaps caused by this financial crisis, but according to Suetonius a result of Caligula's seizure of public carriages,[44] according to Seneca because grain imports were disturbed by Caligula's using grain boats for a pontoon bridge.[51]

Construction

Despite financial difficulties, Caligula embarked on a number of construction projects during his reign. Some were for the public good, while others were for himself.

Josephus describes Caligula's improvements to the harbours at Rhegium and Sicily, allowing increased grain imports from Egypt, as his greatest contributions.[52] These improvements may have been made in response to the famine.[citation needed]

Caligula completed the temple of Augustus and the theatre of Pompey and began an amphitheatre beside the Saepta.[53] He had the imperial palace expanded.[54] He began the aqueducts Aqua Claudia and Anio Novus, which Pliny the Elder considered engineering marvels.[55] He built a large racetrack known as the circus of Gaius and Nero and had an Egyptian obelisk (now known as the Vatican Obelisk) transported by sea and erected in the middle of Rome.[56]

At Syracuse, he repaired the city walls and the temples of the gods.[53] He had new roads built and pushed to keep roads in good condition.[57] He had planned to rebuild the palace of Polycrates at Samos, to finish the temple of Didymaean Apollo at Ephesus and to found a city high up in the Alps.[53] He planned to dig a canal through the Isthmus in Greece and sent a chief centurion to survey the work.[53]

In 39, Caligula performed a spectacular stunt by ordering a temporary floating bridge to be built using ships as pontoons, stretching for over two miles from the resort of Baiae to the neighboring port of Puteoli.[58] It was said that the bridge was to rival that of Persian King Xerxes' crossing of the Hellespont.[58] Caligula, who could not swim,[59] then proceeded to ride his favorite horse, Incitatus, across, wearing the breastplate of Alexander the Great.[58] This act was in defiance of a prediction by Tiberius's soothsayer Thrasyllus of Mendes that Caligula had "no more chance of becoming emperor than of riding a horse across the Bay of Baiae".[58]

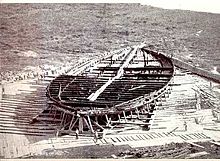

Caligula had two large ships constructed for himself, which were recovered from the bottom of Lake Nemi during the dictatorship of Benito Mussolini. The ships are among the largest vessels in the ancient world. The smaller ship was designed as a temple dedicated to Diana.

The larger ship was essentially an elaborate floating palace that counted marble floors and plumbing among its amenities. Thirteen years after being raised, the ships were burned during an attack in the Second World War, and almost nothing remains of the hulls, though many archeological treasures remain intact in the museum at Lake Nemi and in the Museo Nazionale Romano (Palazzo Massimo) at Rome.

Feud with the Senate

In AD 39, relations between Caligula and the Roman Senate deteriorated.[60] The subject of their disagreement is unknown. A number of factors, though, aggravated this feud. The Senate had become accustomed to ruling without an emperor between the departure of Tiberius for Capri in AD 26 and Caligula's accession.[61] Additionally, Tiberius's treason trials had eliminated a number of pro-Julian senators such as Asinius Gallus.[61]

Caligula reviewed Tiberius's records of treason trials and decided that numerous senators, based on their actions during these trials, were not trustworthy.[60] He ordered a new set of investigations and trials.[60] He replaced the consul and had several senators put to death.[62] Suetonius reports that other senators were degraded by being forced to wait on him and run beside his chariot.[62]

Soon after his break with the Senate, Caligula was met with a number of additional conspiracies against him.[63] A conspiracy involving his brother-in-law was foiled in late 39.[63] Soon afterwards, the governor of Germany, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus, was executed for connections to a conspiracy.[63]

Western expansion

In AD 40, Caligula expanded the Roman Empire into Mauretania and made a significant attempt at expanding into Britannia – even challenging Neptune in his campaign. The conquest of Britannia was fully realized by his successors.

Mauretania

Mauretania was a client kingdom of Rome ruled by Ptolemy of Mauretania. Caligula invited Ptolemy to Rome and then had him suddenly executed.[64] Mauretania was annexed by Caligula and subsequently divided into two provinces, Mauritania Tingitana and Mauretania Caesariensis, separated by the river Malua.[65] Pliny claims that division was the work of Caligula, but Dio states that in 42 AD an uprising took place, which was subdued by Gaius Suetonius Paulinus and Gnaeus Hosidius Geta, only after which the division took place.[66] This confusion might mean that Caligula originally made the decision to divide the province, but the implementation was postponed because of the rebellion.[67] The first known equestrian governor of the two provinces was one Marcus Fadius Celer Flavianus, in office in 44 AD.[67]

Details on the Mauretanian events of 39–44 are unclear. Cassius Dio wrote an entire chapter on the annexation of Mauretania by Caligula, but it is now lost.[68] Caligula's move seemingly had a strictly personal political motive – that is, fear and jealousy of his cousin Ptolemy – and thus the expansion was not set about in response to pressing military or economic needs.[69] However, the rebellion of Tacfarinas had shown how exposed Africa Proconsularis was to its west and how the Mauretanian client kings were unable to provide protection to the province, and it is thus possible that Caligula's expansion was a prudent response to potential future threats.[67]

Britannia

There seemed to be a northern campaign to Britannia that was aborted.[68] This campaign is derided by ancient historians with accounts of Gauls dressed up as Germanic tribesmen at his triumph and Roman troops ordered to collect seashells as "spoils of the sea".[70] The few primary sources disagree on what precisely occurred. Modern historians have put forward numerous theories in an attempt to explain these actions. This trip to the English Channel could have merely been a training and scouting mission.[71] The mission may have been to accept the surrender of the British chieftain Adminius.[72] "Seashells", or conchae in Latin, may be a metaphor for something else such as female genitalia (perhaps the troops visited brothels) or boats (perhaps they captured several small British boats).[73]

Claims of divinity

When several kings came to Rome to pay their respects to him and argued about their nobility of descent, he cried out "Let there be one Lord, one King".[74] In AD 40, Caligula began implementing very controversial policies that introduced religion into his political role. Caligula began appearing in public dressed as various gods and demigods such as Hercules, Mercury, Venus and Apollo.[75] Reportedly, he began referring to himself as a god when meeting with politicians and he was referred to as Jupiter on occasion in public documents.[76][77]

A sacred precinct was set apart for his worship at Miletus in the province of Asia and two temples were erected for worship of him in Rome.[77] The Temple of Castor and Pollux on the Forum was linked directly to the Imperial residence on the Palatine and dedicated to Caligula.[77][78] He would appear here on occasion and present himself as a god to the public. Caligula had the heads removed from various statues of gods and replaced with his own in various temples.[79] It is said that he wished to be worshipped as Neos Helios, the New Sun. Indeed, he was represented as a sun god on Egyptian coins.[80]

Caligula's religious policy was a departure from that of his predecessors. According to Cassius Dio, living emperors could be worshipped as divine in the east and dead Emperors could be worshipped as divine in Rome.[81] Augustus had the public worship his spirit on occasion, but Dio describes this as an extreme act that emperors generally shied away from.[81] Caligula took things a step further and had those in Rome, including Senators, worship him as a physical living god.[82]

Eastern policy

Caligula needed to quell several riots and conspiracies in the eastern territories during his reign. Aiding him in his actions was his good friend, Herod Agrippa, who became governor of the territories of Batanaea and Trachonitis after Caligula became emperor in AD 37.[83]

The cause of tensions in the east was complicated, involving the spread of Greek culture, Roman Law and the rights of Jews in the empire.

Caligula did not trust the prefect of Egypt, Aulus Avilius Flaccus. Flaccus had been loyal to Tiberius, had conspired against Caligula's mother and had connections with Egyptian separatists.[84] In AD 38, Caligula sent Agrippa to Alexandria unannounced to check on Flaccus.[85] According to Philo, the visit was met with jeers from the Greek population who saw Agrippa as the king of the Jews.[86] Flaccus tried to placate both the Greek population and Caligula by having statues of the emperor placed in Jewish synagogues.[87] As a result, riots broke out in the city.[88] Caligula responded by removing Flaccus from his position and executing him.[89]

In AD 39, Agrippa accused Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, of planning a rebellion against Roman rule with the help of Parthia. Herod Antipas confessed and Caligula exiled him. Agrippa was rewarded with his territories.[90]

Riots again erupted in Alexandria in AD 40 between Jews and Greeks.[91] Jews were accused of not honoring the emperor.[91] Disputes occurred in the city of Jamnia.[92] Jews were angered by the erection of a clay altar and destroyed it.[92] In response, Caligula ordered the erection of a statue of himself in the Jewish Temple of Jerusalem,[93] a demand in conflict with Jewish monotheism.[94] In this context, Philo wrote that Caligula "regarded the Jews with most especial suspicion, as if they were the only persons who cherished wishes opposed to his".[94]

The governor of Syria, Publius Petronius, fearing civil war if the order were carried out, delayed implementing it for nearly a year.[95] Agrippa finally convinced Caligula to reverse the order.[91]

Scandals

Philo of Alexandria and Seneca the Younger describe Caligula as an insane emperor who was self-absorbed, angry, killed on a whim, and indulged in too much spending and sex.[96] He is accused of sleeping with other men's wives and bragging about it,[97] killing for mere amusement,[98] deliberately wasting money on his bridge, causing starvation,[99] and wanting a statue of himself erected in the Temple of Jerusalem for his worship.[93] Once, at some games at which he was presiding, he ordered his guards to throw an entire section of the crowd into the arena during intermission to be eaten by animals because there were no criminals to be prosecuted and he was bored.[100]

While repeating the earlier stories, the later sources of Suetonius and Cassius Dio provide additional tales of insanity. They accuse Caligula of incest with his sisters, Agrippina the Younger, Drusilla, and Livilla, and say he prostituted them to other men.[101] They state he sent troops on illogical military exercises,[68][102] turned the palace into a brothel,[45] and, most famously, planned or promised to make his horse, Incitatus, a consul,[103] and actually appointed him a priest.[77]

The validity of these accounts is debatable. In Roman political culture, insanity and sexual perversity were often presented hand-in-hand with poor government.[104]

Assassination and aftermath

Caligula's actions as emperor were described as being especially harsh to the Senate, the nobility and the equestrian order.[105] According to Josephus, these actions led to several failed conspiracies against Caligula.[106] Eventually, a successful murder was planned by officers within the Praetorian Guard led by Cassius Chaerea.[107] The plot is described as having been planned by three men, but many in the Senate, army and equestrian order were said to have been informed of it and involved in it.[108]

The situation escalated when in 40 AD Caligula announced to the Senate that he would be leaving Rome permanently and moving to Alexandria in Egypt, where he hoped to be worshiped as a living god. The prospect of Rome losing its emperor and thus its political power was the final straw for many. Such a move would have left both the Senate and the Praetorian guard powerless to stop Caligula's repression and debauchery. With this in mind Chaerea convinced his fellow conspirators to quickly put their plot into action.

According to Josephus, Chaerea had political motivations for the assassination.[109] Suetonius sees the motive in Caligula calling Chaerea derogatory names.[110] Caligula considered Chaerea effeminate because of a weak voice and for not being firm with tax collection.[111] Caligula would mock Chaerea with names like "Priapus" and "Venus".[112]

On 22 January 41, although Suetonius dates it as 24, Chaerea and other guardsmen accosted Caligula while he was addressing an acting troupe of young men during a series of games and dramatics held for the Divine Augustus.[113] Details on the events vary somewhat from source to source, but they agree that Chaerea was first to stab Caligula, followed by a number of conspirators.[114] Suetonius records that Caligula's death was similar to that of Julius Caesar. He states that both the elder Gaius Julius Caesar (Julius Caesar) and the younger Gaius Julius Caesar (Caligula) were stabbed 30 times by conspirators led by a man named Cassius (Cassius Longinus and Cassius Chaerea).[115]

The cryptoporticus (underground corridor) where this event would have taken place was discovered beneath the imperial palaces on the Palatine Hill.[116] By the time Caligula's loyal Germanic guard responded, the emperor was already dead. The Germanic guard, stricken with grief and rage, responded with a rampaging attack on the assassins, conspirators, innocent senators and bystanders alike.[117]

The Senate attempted to use Caligula's death as an opportunity to restore the Republic.[118] Chaerea attempted to convince the military to support the Senate.[119] The military, though, remained loyal to the office of the emperor.[119] The grieving Roman people assembled and demanded that Caligula's murderers be brought to justice.[120] Uncomfortable with lingering imperial support, the assassins sought out and stabbed Caligula's wife, Caesonia, and killed their young daughter, Julia Drusilla, by smashing her head against a wall.[121] They were unable to reach Caligula's uncle, Claudius, who was spirited out of the city, after being found by a soldier hiding behind a palace curtain,[122] to the nearby Praetorian camp.[123]

Claudius became emperor after procuring the support of the Praetorian guard and ordered the execution of Chaerea and any other known conspirators involved in the death of Caligula.[124] According to Suetonius, Caligula's body was placed under turf until it was burned and entombed by his sisters. He was buried within the Mausoleum of Augustus; in 410 during the Sack of Rome the tomb's ashes were scattered.

Legacy

Historiography

The history of Caligula's reign is extremely problematic as only two sources contemporary with Caligula have survived — the works of Philo and Seneca. Philo's works, On the Embassy to Gaius and Flaccus, give some details on Caligula's early reign, but mostly focus on events surrounding the Jewish population in Judea and Egypt with whom he sympathizes. Seneca's various works give mostly scattered anecdotes on Caligula's personality. Seneca was almost put to death by Caligula in AD 39 likely due to his associations with conspirators.[125]

At one time, there were detailed contemporaneous histories on Caligula, but they are now lost. Additionally, the historians who wrote them are described as biased, either overly critical or praising of Caligula.[126] Nonetheless, these lost primary sources, along with the works of Seneca and Philo, were the basis of surviving secondary and tertiary histories on Caligula written by the next generations of historians. A few of the contemporaneous historians are known by name. Fabius Rusticus and Cluvius Rufus both wrote condemning histories on Caligula that are now lost. Fabius Rusticus was a friend of Seneca who was known for historical embellishment and misrepresentation.[127] Cluvius Rufus was a senator involved in the assassination of Caligula.[128]

Caligula's sister, Agrippina the Younger, wrote an autobiography that certainly included a detailed explanation of Caligula's reign, but it too is lost. Agrippina was banished by Caligula for her connection to Marcus Lepidus, who conspired against Caligula.[63] The inheritance of Nero, Agrippina's son and the future emperor, was seized by Caligula. Gaetulicus, a poet, produced a number of flattering writings about Caligula, but they too are lost.

The bulk of what is known of Caligula comes from Suetonius and Cassius Dio. Suetonius wrote his history on Caligula 80 years after his death, while Cassius Dio wrote his history over 180 years after Caligula's death. Cassius Dio's work is invaluable because it alone gives a loose chronology of Caligula's reign.

A handful of other sources add a limited perspective on Caligula. Josephus gives a detailed description of Caligula's assassination. Tacitus provides some information on Caligula's life under Tiberius. In a now lost portion of his Annals, Tacitus gave a detailed history of Caligula. Pliny the Elder's Natural History has a few brief references to Caligula.

There are few surviving sources on Caligula and no surviving source paints Caligula in a favorable light. The paucity of sources has resulted in significant gaps in modern knowledge of the reign of Caligula. Little is written on the first two years of Caligula's reign. Additionally, there are only limited details on later significant events, such as the annexation of Mauretania, Caligula's military actions in Britannia, and his feud with the Roman Senate.

Health

All surviving sources, except Pliny the Elder, characterize Caligula as insane. However, it is not known whether they are speaking figuratively or literally. Additionally, given Caligula's unpopularity among the surviving sources, it is difficult to separate fact from fiction. Recent sources are divided in attempting to ascribe a medical reason for his behavior, citing as possibilities encephalitis, epilepsy or meningitis. The question of whether or not Caligula was insane (especially after his illness early in his reign) remains unanswered.

Philo of Alexandria, Josephus and Seneca state that Caligula was insane, but describe this madness as a personality trait that came through experience.[90][129][130] Seneca states that Caligula became arrogant, angry and insulting once becoming emperor and uses his personality flaws as examples his readers can learn from.[131] According to Josephus, power made Caligula incredibly conceited and led him to think he was a god.[90] Philo of Alexandria reports that Caligula became ruthless after nearly dying of an illness in the eighth month of his reign in AD 37.[132] Juvenal reports he was given a magic potion that drove him insane.

Suetonius said that Caligula suffered from "falling sickness", or epilepsy, when he was young.[133] Modern historians have theorized that Caligula lived with a daily fear of seizures.[134] Despite swimming being a part of imperial education, Caligula could not swim.[135] Epileptics are discouraged from swimming in open waters because unexpected fits in such difficult rescue circumstances can be fatal.[136] Additionally, Caligula reportedly talked to the full moon.[62] Epilepsy was long associated with the moon.[137]

Some modern historians think that Caligula suffered from hyperthyroidism.[138] This diagnosis is mainly attributed to Caligula's irritability and his "stare" as described by Pliny the Elder.

Possible rediscovery of burial site

On 17 January 2011, police in Nemi, Italy, announced that they believed they had discovered the site of Caligula's burial, after arresting a thief caught smuggling a statue which they believed to be of the emperor.[139] The claim has been met with scepticism by Cambridge historian Mary Beard.[140]

Ancestry

| 16. Drusus Claudius Nero | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Tiberius Claudius Nero | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Claudia | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Nero Claudius Drusus | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Livia Drusilla | |||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Aufidia | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Germanicus | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20. Marcus Antonius Creticus | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Mark Antony | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Julia Antonia | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Antonia Minor | |||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Gaius Octavius (=28) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Octavia Minor | |||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Atia Balba Caesonia (=29) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1.Caligula | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Lucius Vipsanius Agrippa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Agrippina the Elder | |||||||||||||||||||

| 28. Gaius Octavius (=22) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Augustus | |||||||||||||||||||

| 29. Atia Balba Caesonia (=23) | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Julia the Elder | |||||||||||||||||||

| 30. Lucius Scribonius Libo | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Scribonia | |||||||||||||||||||

| 31. Sentia | |||||||||||||||||||

Gallery

-

Quadrans celebrating the abolition of a tax in AD 38 by Caligula. The obverse of the coin contains a picture of the liberty cap which symbolizes the liberation of the people from the tax burden.

-

Roman gold coins excavated in Pudukottai, India, examples of Indo-Roman trade during the period. One coin of Caligula (AD 37–41), and two coins of Nero (AD 54–68). British Museum.

In popular culture

In film

Emlyn Williams was cast as Caligula in the never-completed 1937 film I, Claudius.[141]

American actor Jay Robinson famously portrayed a sinister and scene-stealing Caligula in two epic films of the 1950s, The Robe (1953) and its sequel Demetrius and the Gladiators (1954).[142]

A feature-length historical film Caligula was completed in 1979, in which Malcolm McDowell played the lead role. The film alienated audiences with extremely explicit sex and violence and received extremely negative reviews.[143]

David Brandon portrayed Caligula in the 1982 Italian exploitation film Emperor Caligula, the Untold Story which was directed by Joe D'Amato. [citation needed]

Courtney Love appeared as Caligula in a fake trailer for Gore Vidal's Caligula, ostensibly a remake of the 1979 film, but actually a parodic short film by conceptual artist Francesco Vezzoli.[141]

Szabolcs Hajdu portrayed Caligula in the 1996 film Caligula.[citation needed]

In games and video games

Adult Swim created a game called Viva Caligula for their official website. This game follows the scandalous rumors about Caligula. The user controls Caligula and has a mission to destroy anything in sight. Each letter on the keyboard is a different means of killing the various enemies he encounters.

The video game Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas features a casino named "Caligula's Palace" (a spoof of Caesar's Palace) in the Las Venturas region of the in-game world.

In literature and theatre

Caligula, by French author Albert Camus, is a play in which Caligula returns after deserting the palace for three days and three nights following the death of his beloved sister, Drusilla. The young emperor then uses his unfettered power to "bring the impossible into the realm of the likely".

In the 1934 novel I, Claudius by English writer Robert Graves, Caligula is presented as being a murderous sociopath from his childhood, who became clinically insane early in his reign. At the age of only seven, he drove his father Germanicus to despair and death by secretly terrorising him. Graves's Caligula commits incest with all three of his sisters and is implied to have murdered Drusilla.

In the BBC series based on Graves' novel (where the role is played by John Hurt), Caligula, although unhinged since early childhood, becomes dangerously psychotic after an apparent epileptic seizure and awakens believing that he has metamorphosed into the god Zeus. He kills Drusilla while trying to reenact the birth of Athena by cutting his child from her womb.

In 1941, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote I Am a Barbarian. The story is pitched as a free translation of the memoirs of Britannicus ( a fictional character created by Burroughs) who was the slave of Caligula from early childhood till Caligula's death.

The character Ellsworth Toohey in Ayn Rand's 1943 novel The Fountainhead references Caligula in his climactic speech to Peter Keating stating, "Remember the Roman Emperor who said he wished humanity had a single neck so he could cut it? People have laughed at him for centuries. But we'll have the last laugh. We've accomplished what he couldn't accomplish. We've taught men to unite. This makes one neck ready for one leash."

In 1978, the British comic series 2000AD ran The Day the Law Died, a Judge Dredd comic strip featuring Chief Judge Cal, loosely based on the real life Roman emperor. This was later collected by Titan Books as Judge Caligula.[144]

In Muriel Spark's 1976 novel The Takeover, the eccentric Hubert Mallindaine believes himself to be a direct descendant of Caligula.

The play The Reckoning of Kit and Little Boots, by Nat Cassidy, examines the lives of the Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe and Caligula, with the fictional conceit that Marlowe was working on a play about Caligula around the time of his own murder. It emphasizes the similarities between the two characters—both stabbed to death at 29, both in part as a result of their controversial religious perspectives. The play focuses on Caligula's love for his sister Drusilla and his deep-rooted loathing for Tiberius. It received its world premiere in New York City in June 2008.[145][146]

In 2011, Avatar Press began publishing a comic book Caligula written by horror comic writer David Lapham.

In music

In January 2013, Comedian Anthony Jeselnik released his live stand-up comedy album, titled, "Caligula."

Canadian death metal band Ex Deo released an album called Caligula, styled as Caligvla. The band's video, "I Caligula", features Caligula and other members of his court that were important in his rule.

The Smiths song "Heaven Knows I'm Miserable Now" refers to Caligula: "What she asked of me at the end of the day/Caligula would have blushed".

The Dickies' 1989 album Second Coming includes the song "Caligula," which relates his origins and reign of terror.

Post-hardcore band Glassjaw's song "Convectuoso" refers to Caligula in the opening lines: "I am Caligula, glutton of gluttons, man over woman, man of all women, the whore of all man."

Flipmode Squad song "To My People" Busta Rhymes refers to Caligula: "Roll with my squad or go singular; I ain't into bitches who fuck animals like Caligula."

The supergroup Them Crooked Vultures' original name was "Caligulove" though due to legal issues they were forced to change it. They also recorded a song named "Caligulove" on their self-titled album, the song's lyrics and imagery depict delusions of grandeur, megalomania, sado-masochistic fetishes (or rather alludes to it) and power dynamics and power struggles in relationships.

Dead Kennedys leader and social commentator Jello Biafra has repeatedly referred to former US president Ronald Reagan as "Grandpa Caligula" in his spoken word performances.

In television

Caligula has been played by Ralph Bates in the 1968 ITV television series The Caesars; John Hurt in the 1976 BBC television series I, Claudius; John McEnery in the 1985 miniseries A.D.; Tony Hawks in the Red Dwarf episode "Meltdown" (1991); Simon Farnaby in "Horrible Histories" and John Simm in the 2004 miniseries Imperium Nerone.

References

Notes

- ^ In Classical Latin, Caligula's name would be inscribed as GAIVS IVLIVS CAESAR AVGVSTVS GERMANICVS.

- ^ a b c d e Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 7.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.6.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 9.

- ^ "Caligula" is formed from the Latin word caliga, meaning soldier's boot, and the diminutive infix -ul.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of a Wise Person XVIII 2–5. See Malloch, 'Gaius and the nobiles', Athenaeum (2009).

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 10.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals IV.52.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.3.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 54.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals V.10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 64.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 62.

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals VI.20.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 12

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 11

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LVII.23.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.25.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals VI.23.

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 12.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius VI.35.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 76.

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals VI.50.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius IV.25; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIII.6.9.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.1.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 13.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Tiberius 75.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 14.

- ^ Philo mentions widespread sacrifice, but no estimation on the degree, Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.12.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II.13.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 15.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 18.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.3.

- ^ Dunstan, William E., Ancient Rome, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2010, ISBN 0-7425-6834-2, p.285.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 23

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9–10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 16.2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.9.7.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.10.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37.

- ^ a b c Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 38.

- ^ a b Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 41.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 40.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Nero 30

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life XVIII.5.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.5.

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 22.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 21, Life of Claudius 20; Pliny the Elder, Natural History XXXVI.122.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History XVI.76.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.15; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 37.

- ^ a b c d Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 19.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 54.

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.16; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 30.

- ^ a b Tacitus, Annals IV.41.

- ^ a b c Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 26.

- ^ a b c d Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.22.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 35.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, Natural History V.2.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LX.8

- ^ a b c Barrett 2002, p. 118

- ^ a b c Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.25.

- ^ Sigman, Marlene C. (1977). "The Romans and the Indigenous Tribes of Mauritania Tingitana". Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. 26 (4). Franz Steiner Verlag: 415–439. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 45–47.

- ^ P. Bicknell, "The Emperor Gaius' Military Activities in AD 40", Historia 17 (1968), 496–505.

- ^ R.W. Davies, "The Abortive Invasion of Britain by Gaius", Historia 15 (1966), 124–128; S.J.V.Malloch, 'Gaius on the Channel Coast', Classical Quarterly 51 (2001) 551-56; See Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 44.

- ^ D. Wardle, Suetonius' Life of Caligula: a Commentary (Brussels, 1994), 313; David Woods "Caligula's Seashells", Greece and Rome (2000), 80–87.

- ^ The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 22

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XI–XV.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26.

- ^ a b c d Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.28.

- ^ Sanford, J.: "Did Caligula have a God complex?, Stanford Report, 10 September 2003.[dead link]

- ^ Farquhar, Michael (2001). A Treasure of Royal Scandals, p. 209. Penguin Books, New York. ISBN 0-7394-2025-9.

- ^ Allen Ward, Cedric Yeo, and Fritz Heichelheim, A History of the Roman People: Third Edition, 1999, Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- ^ a b Cassius Dio, Roman History LI.20.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.26–28.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.6.10; Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.25.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus III.8, IV.21.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.26–28.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus V.29.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VI.43.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus VII.45.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, Flaccus XXI.185.

- ^ a b c Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.7.2.

- ^ a b c Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XVIII.8.1.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.201.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXX.203.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XVI.115.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXXI.213.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger xviii.1, On Anger III.xviii.1; On the Shortness of Life xviii.5; Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XXIX.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.1.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Anger III.xviii.1.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Shortness of Life xviii.5.

- ^ "Daily life in the Roman City". Aldrete, Gregory.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.11, LIX.22; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 24.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 46–47.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 55; Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.14.

- ^ Younger, John G. (2005). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. xvi. ISBN 0-415-24252-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.1.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56; Tacitus, Annals 16.17; Josephus, Antiquities of Jews XIX.1.2.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.3.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.10, XIX.1.14.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.6.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.5.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 56.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On Firmness xviii.2; Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 58; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.14.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 57, 58.

- ^ Archaeologists unearth place where Emperor Caligula met his end by Richard Owen, 17 October 2008. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.15; Suetonius, Life of Caligula 58.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.

- ^ a b Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.4.4.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals XI.1; Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.20.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 59.

- ^ Suetonius. The Lives.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.2.1.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.3.1.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History LIX.19.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals I.1.

- ^ Tacitus, Life of Gnaeus Julius Agricola X, Annals XIII.20.

- ^ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews XIX.1.13.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius XIII.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVIII.1; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8.

- ^ Seneca the Younger, On the Firmness of the Wise Person XVII–XVIII; Seneca the Younger, On Anger I.xx.8.

- ^ Philo of Alexandria, On the Embassy to Gaius II–IV.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula 50.

- ^ D. Thomas Benediktson, "Caligula's Phobias and Philias: Fear of Seizure?", The Classical Journal (1991) pp. 159–163.

- ^ Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Augustus 64, Life of Caligula 54.

- ^ J.H. Pearn, "Epilepsy and Drowning in Childhood," British Medical Journal (1977) pp. 1510–11.

- ^ O. Temkin, The Falling Sickness (2nd ed., Baltimore 1971) 3–4, 7, 13, 16, 26, 86, 92–96, 179.

- ^ R.S. Katz, "The Illness of Caligula" CW 65(1972),223-25, refuted by M.G. Morgan, "Caligula's Illness Again", CW 66(1973), 327–29.

- ^ Kington, Tom (17 January 2011). "Caligula's tomb found after police arrest man trying to smuggle statue". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Beard, Mary (18 January 2011). "This isn't Caligula's tomb". A don's life. London: The Times. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Yablonsky, Linda (26 February 2006). "'Caligula' Gives a Toga Party (but No One's Really Invited)". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

- ^ Robinson, Jay. The Comeback. Word Books, 1979. ISBN 978-0-912376-45-5

- ^ Caligula > Overview – AllMovie.com. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ^ Barney Reprint Zone

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ "Episode #223 – The Reckoning of Kit & Boots and Hope's Arbor". NYTHEATRECAST. The New York Theatre Experience. 4 June 2008. Archived from the original (Podcast (MP3)) on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 30 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Primary sources

- Cassius Dio, Roman History, Book 59

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, (trans. W.Whiston), Books XVIII–XIX

- Philo of Alexandria, (trans. C.D.Yonge, London, H. G. Bohn, 1854–1890):

- Seneca the Younger

- Suetonius, The Lives of Twelve Caesars, Life of Caligula

- Tacitus, Annals, Book 6

- Secondary material

- Balsdon, V. D. (1934). The Emperor Gaius. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Barrett, Anthony A. (1989). Caligula: the corruption of power. London: Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-5487-3.

- Grant, Michael (1979). The Twelve Caesars. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-044072-0.

- Hurley, Donna W. (1993). An Historical and Historiographical Commentary on Suetonius' Life of C. Caligula. Atlanta: Scholars Press.

- Sandison, A. T. (1958). "The Madness of the Emperor Caligula". Medical History. 2: 202–209. doi:10.1017/s0025727300023759.

- Wilcox, Amanda (2008). "Nature's Monster: Caligula as exemplum in Seneca's Dialogues". In Sluiter, Ineke; Rosen, Ralph M. (eds.). Kakos: Badness and Anti-value in Classical Antiquity. Mnemosyne: Supplements. History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity. Vol. 307. Leiden: Brill.

External links

- Caligula Attempts to Conquer Britain in AD 40

- Biography from De Imperatoribus Romanis

- Biography of Gaius Caligula

- Straight Dope article

- Caligula

- A chronological account of his reign

- Caligula at BBC History

- Caligula at BBC Online

Template:Persondata Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA