Chaldean Catholics

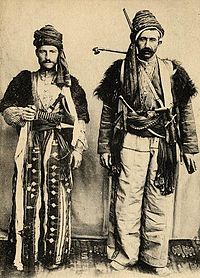

Chaldo-Assyrian Catholics from Mardin, 19th century. | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 550,000 | |

| 40,000 | |

| 20,000 | |

| 8,000 | |

| Religions | |

| Syriac Christianity (in union with Rome), Chaldean Catholic Church | |

| Scriptures | |

| The Bible | |

| Languages | |

| Neo-Aramaic (Assyrian Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean Neo-Aramaic), Arabic | |

Chaldean Christians /kælˈdiːən/ (ܟܠܕܝ̈ܐ), or Chaldo-Assyrians,[1][2] adherents of the Chaldean Catholic Church, originally called The Church of Assyria and Mosul,[3] which was that part of the Assyrian Church of the East which entered communion with the Catholic Church between the 16th and 18th centuries.[4]

In addition to their ancient Assyrian homeland in northern Iraq, northeast Syria, northwest Iran and southeast Turkey, (a region roughly corresponding with ancient Assyria) migrant Assyrian or Chaldo-Assyrian Catholic communities are found in the United States, Sweden, Germany, France, Canada, Lebanon, Jordan and Australia.[5]

Etymology

The terms Chaldean and Chaldo-Assyrian are sometimes used to describe those Assyrians from northern Mesopotamia who broke from the Assyrian Church of the East and entered communion with the Roman Catholic Church, after at first failing to gain acceptance within the Syriac Orthodox Church.[6] Rome initially named this new diocese The Church of Assyria and Mosul in 1553, and only some 128 years later, in 1681, was this changed to The Chaldean Catholic Church, despite none of its adherents (or neighbouring peoples) having hitherto used the name "Chaldean" to describe themselves or their church,[7][8][9] or having originated in the region in the far south of Mesopotamia which had long ago once been Chaldea. This line also drifted back to the Assyrian Church, however a decade or so before it did so another group of Assyrians entered communion with Rome, and it was this line which eventually became the modern Chaldean Catholic Church in 1830 AD.[10]

The term Chaldean in reference to followers the Chaldean Catholic Church is thus properly taken as only a denominational, theological and ecclesiastical term and not an ethnic one, and is a misnomer in relation to ancient Chaldea and its inhabitants, both of which only emerged during the 9th century BC and disappeared from history during the 6th century BC at the exact opposite end of Mesopotamia, Chaldean Catholics instead being regarded ethnically and historically as Assyrians, and as a part of the Assyrian continuity.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

Similarly, Chaldean Catholics should not be confused with the Saint Thomas Christians of India (also called the Chaldean Syrian Church), who are also sometimes known as "Chaldean Christians" or Assyrian Christians, nor with the people of Chaldia on the Black Sea.

History

It is believed that the term Chaldean Catholic arose due to a Catholic Latin misinterpretation and misreading of the Hebrew Ur Kasdim (according to long held Jewish tradition, the birthplace of Abraham in Northern Mesopotamia) as meaning Ur of the Chaldees.[19] The Hebrew Kasdim does not in fact mean or refer to the Chaldeans, and Ur Kasdim is generally believed by many to have been somewhere in Assyria, north eastern Syria or south eastern Anatolia.

The 18th century Roman Catholic Church then applied this misinterpreted name to their new diocese in northern Mesopotamia, a region whose indigenous inhabitants had always previously been referred to ethnically as Assurayu, Assyrians, Assouri, Ashuriyun, East Syrian, Athurai, Atoreh etc., and by the denominational terms Syriac Christians, Jacobites and Nestorians. The term Syrian and its derivative Syriac, are themselves 9th century BC Anatolian corruptions of Assyrian.

Thus the term Chaldean Catholic is historically, usually and properly taken purely as a denominational, doctrinal and theological term which only arose in the late 17th century AD and became fully established in the 19th century AD, and not as an ethnic, historical or geographical identity or designation.[20][21][21]

The modern Chaldean Catholics are in fact Assyrians[22] and originated from ancient Assyrian communities living in and indigenous to the north of Iraq/Mesopotamia which was known as Assyria from the 25th century BC until the 7th century AD, rather than the long extinct Chaldeans/Chaldees, who in actuality were 9th century BC migrants from The Levant, and always resided in the far south east of Mesopotamia, and disappeared from history circa 550 BC. However, despite this, a minority of Chaldean Catholics (particularly in the United States) have in recent times confused a purely religious term with an ethnic identity, and espoused a separate ethnic identity to their Assyrian brethren, despite there being absolutely no historical, academic, cultural, geographic, archaeological, linguistic or genetic evidence supporting a link to either the Chaldean land or the Chaldean race.

Raphael Bidawid, the then patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church commented on the Assyrian name dispute in 2003 and clearly differentiated between the name of a church and an ethnicity:

- “I personally think that these different names serve to add confusion. The original name of our Church was the ‘Church of the East’ … When a portion of the Church of the East became Catholic in the 17th Century, the name given was ‘Chaldean’ based on the Magi kings who were believed by some to have come from what once had been the land of the Chaldean, to Bethlehem. The name ‘Chaldean’ does not represent an ethnicity, just a church… We have to separate what is ethnicity and what is religion… I myself, my sect is Chaldean, but ethnically, I am Assyrian.”[23]

In an interview with the Assyrian Star in the September–October 1974 issue, he was quoted as saying:

- “Before I became a priest I was an Assyrian, before I became a bishop I was an Assyrian, I am an Assyrian today, tomorrow, forever, and I am proud of it.”[18]

Brief history of Chaldean Catholics in the Middle East

The Assyrians of all denominations suffered a number of religiously and ethnically motivated massacres throughout the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries,[24] culminating in the large scale Hamidian massacres of unarmed men, women and children by Muslim Turks and Kurds in the late 19th century at the hands of the Ottoman Empire and its associated (largely Kurdish and Arab) militias, which further greatly reduced numbers, particularly in southeastern Turkey.

A further catastrophic series of events occurred during World War I in the form of the religiously and ethnically motivated Assyrian Genocide at the hands of the Ottomans and their Kurdish and Arab allies from 1915 to 1918.[25][26][27][28] Some sources claim the highest number of Assyrians killed during the period was 750,000, while a 1922 Assyrian assessment set it at 275,000. The Assyrian Genocide ran largely in conjunction to the similarly motivated Armenian Genocide and Greek Genocide.

In reaction against Turkish cruelty, Assyrians took up arms, and an Assyrian war of independence was fought during World War I. For a time, the Assyrians fought successfully against overwhelming numbers, scoring a number of victories over the Ottomans and Kurds, and also hostile Arab and Iranian groups; then their Russian allies left the war following the Russian Revolution, and Armenian resistance broke. The Assyrians were left cut off, surrounded, and without supplies, forcing those in Asia Minor and Northwest Iran to fight their way, with civilians in tow, to the safety of British lines and their fellow Assyrians in northern Iraq. The sizeable Assyrian presence in south eastern Anatolia which had endured for over four millennia was thus reduced to no more than 15,000 by the end of World War I.

In 1963, the Ba'ath Party took power by force in Iraq. The Baathists, though secular, were Arab nationalists, and set about attempting to Arabize the many non-Arab peoples of Iraq, including the Assyrians. Other non-Arab ethnic groups targeted for forced Arabization included Kurds, Armenians, Turcomans, Mandeans, Yezidi, Shabaki, Kawliya, Persians and Circassians. This policy included refusing to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group, banning the publication of written material in Eastern Aramaic, and banning its teaching in schools, banning parents giving Assyrian names to their children, banning Assyrian political parties, taking control of Assyrian churches, attempting to create divisions amongst Assyrians on denominational lines (e.g. Assyrian Church of the East vs Chaldean Catholic Church vs Syriac Orthodox vs Assyrian Protestant), forced relocations of Assyrians from their traditional homelands to major cities, together with an attempt to Arabize the ancient pre-Arab heritage of Mesopotamian civilisation. In response to Baathist persecution, the Assyrians of the Zowaa movement within the Assyrian Democratic Movement took up armed struggle against the Iraqi regime in 1982 under the leadership of Yonadam Kanna,[29] and then joined up with the IKF in early 1990s. Yonadam Kanna in particular was a target of the Ba'ath regime for many years.

The policies of the Baathists have also long been mirrored in Turkey, whose nationalist governments have refused to acknowledge the Assyrians as an ethnic group since the 1920s, and have attempted to Turkify the Assyrians by calling them "Semitic Turks" and forcing them to adopt Turkish names and language. In Baathist Syria too, the Assyrian (and Syriac-Aramean) Christians faced pressure to identify as "Arab Christians", while in Iran, Assyrians continued to enjoy full cultural, religious and ethnic rights for a time, until the Islamic Revolution of 1979, where after they suffered by being forcibly subject to strict Islamic Law.

Many persecutions have befallen the Assyrians since, such as the Anfal campaign and Baathist, Arab, Kurdish, Turkish nationalist and Islamist persecutions.

In recent years, particularly since 2014, the Assyrians of all denominations in northern Iraq and north east Syria have become the target of unprovoked Islamic terrorism. As a result, Assyrians have taken up arms, alongside other groups (such as the Kurds, Turcomans and Armenians) in response to unprovoked attacks by Al Qaeda, ISIL, Nusra Front, and other Wahhabi terrorist Islamic fundamentalist groups. In 2014 Islamic terrorists of ISIS attacked Assyrian towns and villages in the Assyrian homelands of northern Iraq and north east Syria, together with cities such as Mosul, Kirkuk and Hasakeh which have large Assyrian populations. There have been reports of a litany of religiously motivated atrocities committed by ISIS terrorists since, including; beheadings, crucifixions, child murders, rape of women and girls, torture, forced conversions, ethnic cleansing, robbery, kidnappings, theft of homes, and extortion in the form of illegal taxes levied upon non Muslims. Assyrians forced from their homes in cities such as Mosul have had their houses and possessions stolen, and given over to ISIS terrorists or Sunni Arabs.[30]

In addition, the Assyrians have suffered seeing their ancient indigenous heritage desecrated, in the form of Bronze Age and Iron Age monuments and archaeological sites, as well as numerous Assyrian churches and monasteries,[30] being systematically vandalised and destroyed by ISIS. These include the ruins of Nineveh, Kalhu (Nimrud, Assur, Dur-Sharrukin and Hatra.[31][32]

Assyrians in both northern Iraq and north east Syria[33][34] have responded by forming armed Assyrian militias to defend their territories,[35] and despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned have had success in driving ISIS from Assyrian towns and villages, and defending others from attack.[36][37] Armed Assyrian militias have also joined forces with other peoples persecuted by ISIS and Sunni Muslim extremists, including; the Kurds, Turcoman, Yezidis, Syriac-Aramean Christians, Shabaks, Armenian Christians, Kawilya, Mandeans, Circassians and Shia Muslim Arabs and Iranians.

The 1896 census of the Chaldean Catholics[38] counted 233 parishes and 177 churches or chapels, mainly in northern Iraq and southeastern Turkey. The Chaldean Catholic clergy numbered 248 priests; they were assisted by the monks of the Congregation of St. Hormizd, who numbered about one hundred. There were about 52 Assyrian Chaldean schools (not counting those conducted by Latin nuns and missionaries). At Mosul there was a patriarchal seminary, distinct from the Chaldean seminary directed by the Dominicans. The total number of Assyrian Chaldean Christians is nearly 1.4 million, 78,000 of whom are in the Diocese of Mosul.

The current patriarch considers Baghdad as the principal city of his see. His title of "Patriarch of Babylon" results from the identification of Baghdad with ancient Babylon (however Baghdad is 55 miles north of the ancient city of Babylon and corresponds to northern Babylonia). However, the Chaldean patriarch resides habitually at Mosul in the north, and reserves for himself the direct administration of this diocese and that of Baghdad.

There are five archbishops (resident respectively at Basra, Diyarbakır, Kirkuk, Salmas and Urmia) and seven bishops. Eight patriarchal vicars govern the small Assyrian Chaldean communities dispersed throughout Turkey and Iran. The Chaldean clergy, especially the monks of Rabban Hormizd Monastery, have established some missionary stations in the mountain districts dominated by The Assyrian Church of the East. Three dioceses are in Iran, the others in Turkey.

The liturgical language of the Chaldean Catholic Church is Syriac, a Neo-Aramaic dialect originating in 5th century BC Achaemenid Assyria (Athura) during the Achaemenid Empire. The liturgy of the Chaldean Church is written in the Syriac alphabet.

The literary revival in the early 20th century was mostly due to the Lazarist Pere Bedjan, an ethnic Assyrian Chaldean Catholic from north western Iran. He popularized the ancient chronicles, the lives of Assyrian saints and martyrs, and even works of the ancient Assyrian doctors among Assyrians of all denominations, including Chaldean Catholics, Syriac Orthodox, Assyrian Church of the East and Assyrian Protestants.[39]

In March 2008, Chaldean Catholic Archbishop Paulos Faraj Rahho of Mosul was kidnapped, and found dead two weeks later. Pope Benedict XVI condemned his death. Sunni and Shia leaders also expressed their condemnation.[40]

Chaldean Catholics today number approximately 550,000 of Iraq's estimated 800,000-1,000,000 Assyrian Christians, with smaller numbers found among the Assyrian Christian communities of northeast Syria, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel and Armenia.[4] Perhaps the best known Iraqi Chaldean Catholic is former Iraqi deputy prime minister, Tariq Aziz (real name Michael Youhanna).[4]

Hundreds of thousands of Assyrian Christians of all denominations have left Iraq since the ousting of Saddam Hussein in 2003. At least 20,000 of them have fled through Lebanon to seek resettlement in Europe and the US.[41]

As political changes sweep through many Arab nations, the ethnic Assyrian minorities in northeast Syria, northwest Iran and southeast Turkey have also expressed concern.[42]

Predominantly Chaldean Catholic towns in northern Iraq

- Zakho

- Alqosh (ܐܠܩܘܫ)

- Ankawa (ܥܢܟܒ݂ܐ)

- Araden (ܐܪܕܢ)

- Baqofah (ܒܝܬ ܩܘܦ̮ܐ)

- Batnaya (ܒܛܢܝܐ)

- Karamles (ܟܪܡܠܫ)

- Shaqlawa(ܫܩܠܒ݂ܐ)

- Tel Isqof (ܬܠܐ ܙܩܝܦ̮ܐ)

- Tel Keppe (ܬܠ ܟܦܐ)

See also

- Assyrian people

- Assyrian continuity

- List of Assyrians

- Names of Syriac Christians

- Ancient Church of the East

- Assyrian Church of the East

- Syriac Orthodox Church

- Assyrian Pentecostal Church

- Assyrian Evangelical Church

- Assyrian genocide

- Assyria

- Babylonia

- Chaldea

- Achaemenid Assyria

- Athura

- Assuristan

- Upper Mesopotamia

- East Syrian Rite

- Emmanuel III Delly

- List of Assyrian settlements

- Etymology of Syria

- Syriac language

- Assyrian diaspora

- Semitic people

References

- ^ Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5

- ^ Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies (JAAS) 18 (2): pp. 22.

- ^ George V. Yana (Bebla), "Myth vs. Reality" JAA Studies, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 2000 p. 80

- ^ a b c BBC NEWS (March 13, 2008). "Who are the Chaldean Christians?". BBC NEWS. Retrieved March 26, 2010.

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Iraq. Scarecrow Press. 2004. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-8108-4330-1.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Dr. Layla Maleh (Kuwait University) (2009). Arab Voices in Diaspora: Critical Perspectives on Anglophone Arab Literature. Rodopi. p. 396. ISBN 90-420-2718-5.

- ^ “A difficulty now arose; the new converts styled themselves 'Sooraye' and 'Nestornaye' . The Romanists could not call them 'Catholic Syrians' or 'Syrian Catholics' for this appellation they had already given to their proselytes from the Jacobites, who also called themselves 'Syrians'. They could not term them 'Catholic Nestorians,' as Mr. Justin Perkins, the independent American missionary does, for this would involve a contradiction. What more natural, then, than that they should have applied to them the title of 'Chaldeans' to which they had some claims of nationality, in virtue of their Assyrian Descent.” - Asshur and the Land of Nimrod” by Hormuzd Rassam

- ^ Qaryaneh Jobyeh" - Mar Toma Audo. 1906

- ^ Arabs and Christians? Christians in the Middle East” by Antonie Wessels

- ^ D.Wilmshurst - A History of The Church of the East

- ^ Rassam, H. (1897), Asshur and the Land of Nimrod London

- ^ Soane, E.B. To Mesopotamia and Kurdistan in Disguise John Murray: London, 1912 p. 92

- ^ Rev. W.A. Wigram (1929), The Assyrians and Their Neighbours London

- ^ Efram Yildiz's "The Assyrians" Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies, 13.1, pp. 22, ref 24

- ^ Assyrians After Assyria, Parpola

- ^ “The Eastern Christian Churches” by Ronald Roberson. “In 1552, when the new patriarch was elected, a group of Assyrian bishops refused to accept him and decided to seek union with Rome. They elected the reluctant abbot of a monastery, Yuhannan Sulaqa, as their own patriarch and sent him to Rome to arrange a union with the Catholic Church. In early 1553 Pope Julius III proclaimed him Patriarch Simon VIII “of the Chaldeans” and ordained him a bishop in St. Peter’s Basilica on April 9, 1553

- ^ Aqaliyat shimal al-‘Araq; bayna al-qanoon wa al-siyasa” (Northern Iraq Minorities; between Law and Politics) by Dr. Jameel Meekha Shi’yooka

- ^ a b Mar Raphael J Bidawid. The Assyrian Star. September–October, 1974:5.

- ^ Biblical Archaeology Review May/June 2001: Where Was Abraham's Ur? by Allan R. Millard

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Travis, Hannibal. Genocide in the Middle East: The Ottoman Empire, Iraq, and Sudan. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press, 2010, 2007, pp. 237-77, 293–294

- ^ a b http://conference.osu.eu/globalization/publ/08-bohac.pdf

- ^ Nisan, M. 2002. Minorities in the Middle East: A History of Struggle for Self Expression .Jefferson: McFarland & Company. Jump up ^ http://www.upenn.edu/pennpress/book/14225.html

- ^ Parpola, Simo (2004). "National and Ethnic Identity in the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Assyrian Identity in Post-Empire Times" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 18 (2). JAAS: 22.

- ^ Aboona, H (2008). Assyrians and Ottomans: intercommunal relations on the periphery of the Ottoman Empire. Cambria Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 978-1-60497-583-3.

- ^ Akçam, Taner (2012). The Young Turks' Crime against Humanity: The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press. pp. xx–xxi. ISBN 978-1-4008-4184-4. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Genocide Scholars Association Officially Recognizes Assyrian Greek Genocides. 16 December 2007. Retrieved 2010-02-02

- ^ Khosoreva, Anahit. "The Assyrian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire and Adjacent Territories" in The Armenian Genocide: Cultural and Ethical Legacies. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 2007, pp. 267–274. ISBN 1-4128-0619-4.

- ^ Travis, Hannibal. "Native Christians Massacred: The Ottoman Genocide of the Assyrians During World War I." Genocide Studies and Prevention, Vol. 1, No. 3, December 2006.

- ^ "زوعا". Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ a b "ISIS destroy the oldest Christian monastery in Mosul, Iraq". NewyorkNewsgrio.com. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "ISIL video shows destruction of Mosul artefacts", Al Jazeera, 27 Feb 2015

- ^ Buchanan, Rose Troup and Saul, Heather (25 February 2015) Isis burns thousands of books and rare manuscripts from Mosul's libraries The Independent

- ^ Sheren KhalelMatthew Vickery (25 February 2015). "Syria's Christians Fight Back". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Martin Chulov. "Christian militia in Syria defends ancient settlements against Isis". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Matt Cetti-Roberts. "Inside the Christian Militias Defending the Nineveh Plains — War Is Boring". Medium. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "8 things you didn't know about Assyrian Christians". PBS NewsHour. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Patrick Cockburn (22 February 2015). "Isis in Iraq: Assyrian Christian militia keep well-armed militants at bay - but they are running out of ammunition". The Independent. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ Mgr. George 'Abdisho' Khayyath to the Abbé Chabot (Revue de l'Orient Chrétien, I, no. 4)

- ^ "New Advent Catholic Encyclopedia".

- ^ "Iraqi archbishop death condemned". BBC News. 2008-03-13. Retrieved 2009-12-31. from BBC News

- ^ Martin Chulov (2010) ”Christian exodus from Iraq gathers pace”The Guardian, retrieved June 12, 2012

- ^ R. Thelen (2008) Daily Star, Lebanon retrieved June 12, 2012

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)