1991 Croatian independence referendum

| 1991 Croatian independence referendum | ||

|---|---|---|

| Electorate | 3,652,225 | |

| Turnout | (83.56%) 3,051,881 | |

| Supporting sovereignty and independence of Croatia | ||

| Voting options | Votes | % |

| Yes | 2,845,521 | 93.24 |

| No | 126,630 | 4.15 |

| Supporting Croatia remaining in federal Yugoslavia | ||

| Voting options | Votes | % |

| Yes | 164,267 | 5.38 |

| No | 2,813,085 | 92.18 |

| Source: State Election Committee[1] | ||

|

|---|

Croatia held an independence referendum on 19 May 1991, following the Croatian parliamentary elections of 1990 and the rise of ethnic tensions that led to the breakup of Yugoslavia. With 83 percent turnout, voters approved the referendum, with 93 percent in favor of independence. Subsequently, Croatia declared independence and the dissolution of its association with Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991, but it introduced a three-month moratorium on the decision when urged to do so by the European Community and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe through the Brioni Agreement. The war in Croatia escalated during the moratorium, and on 8 October 1991, the Croatian Parliament severed all remaining ties with Yugoslavia. In 1992, the countries of the European Economic Community granted Croatia diplomatic recognition and Croatia was admitted to the United Nations.

Background

[edit]

After World War II, Croatia became a one-party socialist federal unit of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Croatia was ruled by the League of Communists and enjoyed a degree of autonomy within the Yugoslav federation. In 1967, a group of Croatian authors and linguists published the Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Literary Language, demanding greater autonomy for the Croatian language.[2] The declaration contributed to a national movement seeking greater civil rights and decentralization of the Yugoslav economy, culminating in the Croatian Spring of 1971, which was suppressed by Yugoslav leadership.[3] The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution gave increased autonomy to federal units, essentially fulfilling a goal of the Croatian Spring and providing a legal basis for independence of the federative constituents.[4]

In the 1980s, the political situation in Yugoslavia deteriorated, with national tension fanned by the 1986 Serbian SANU Memorandum and the 1989 coups in Vojvodina, Kosovo and Montenegro.[5][6] In January 1990, the Communist Party fragmented along national lines, with the Croatian faction demanding a looser federation.[7] In the same year, the first multi-party elections were held in Croatia, with Franjo Tuđman's win resulting in further nationalist tensions.[8] The Croatian Serb politicians boycotted the Sabor, and local Serbs seized control of Serb-inhabited territory, setting up road blocks and voting for those areas to become autonomous. The Serb "autonomous oblasts" would soon unite to become the internationally unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina (RSK),[9][10] intent on achieving independence from Croatia.[11][12]

Referendum and declaration of independence

[edit]

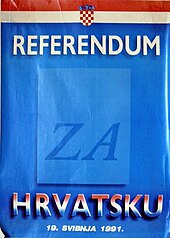

On 25 April 1991, the Croatian Parliament decided to hold an independence referendum on 19 May. The decision was published in the official gazette of the Republic of Croatia and made official on 2 May 1991.[13] The referendum offered two options. In the first, Croatia would become a sovereign and independent state, guaranteeing cultural autonomy and civil rights to Serbs and other minorities in Croatia, free to form an association of sovereign states with other former Yugoslav republics. In the second, Croatia would remain in Yugoslavia as a unified federal state.[13][14] Serb local authorities called for a boycott of the vote.[15] Alternative counter-referendum was held a week earlier in Serb controlled areas where voters were asked if they want to remain a part of Yugoslavia and with this referendum being delayed in SAO Eastern Slavonia where it took place on the same day as the Croatian independence referendum.[16] The Croatian independence referendum was held at 7,691 polling stations, where voters were given two ballots—blue and red, with a single referendum option each, allowing use of either or both of ballots. The referendum question proposing independence of Croatia, presented on the blue ballot, passed with 93.24% in favor, 4.15% against, and 1.18% of invalid or blank votes. The second referendum question, proposing that Croatia should remain in Yugoslavia, was declined with 5.38% votes in favor, 92.18% against and 2.07% of invalid votes. The turnout was 83.56%.[1]

Croatia subsequently declared independence and dissolved (Croatian: razdruženje) its association with Yugoslavia on 25 June 1991.[17][18] The European Economic Community and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe urged Croatian authorities to place a three-month moratorium on the decision.[19] Croatia agreed to freeze its independence declaration for three months, initially easing tensions.[20] Nonetheless, the Croatian War of Independence escalated further.[21] On 7 October, the eve of expiration of the moratorium, the Yugoslav Air Force attacked Banski dvori, the main government building in Zagreb.[22][23] On 8 October 1991, the moratorium expired, and the Croatian Parliament severed all remaining ties with Yugoslavia. That particular session of the parliament was held in the INA building in Šubićeva Street in Zagreb due to security concerns provoked by the aforementioned Yugoslav air raid;[24] specifically, it was feared that the Yugoslav Air Force might attack the parliament building.[25] 8 October was celebrated as Croatia's Independence Day for a while. Nowadays, October 8 is the Memorial Day of the Croatian Parliament and no longer a public holiday.[26]

Recognition

[edit]

The Badinter Arbitration Committee was set up by the Council of Ministers of the European Economic Community (EEC) on 27 August 1991 to provide legal advice and criteria for diplomatic recognition to former Yugoslav republics.[27] In late 1991, the Commission stated, among other things, that Yugoslavia was in the process of dissolution, and that the internal boundaries of Yugoslav republics could not be altered unless freely agreed upon.[28] Factors in the preservation of Croatia's pre-war borders, defined by demarcation commissions in 1947,[29] were the Yugoslav federal constitutional amendments of 1971 and 1974, granting that sovereign rights were exercised by the federal units, and that the federation had only the authority specifically transferred to it by the constitution.[4][30]

Germany advocated quick recognition of Croatia, stating that it wanted to stop ongoing violence in Serb-inhabited areas. It was opposed by France, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, but the countries agreed to pursue a common approach and avoid unilateral actions. On 10 October, two days after the Croatian Parliament confirmed the declaration of independence, the EEC decided to postpone any decision to recognize Croatia for two months, deciding to recognize Croatian independence in two months if the war had not ended by then. As the deadline expired, Germany presented its decision to recognize Croatia as its policy and duty—a position supported by Italy and Denmark. France and the UK attempted to prevent the recognition by drafting a United Nations resolution requesting no unilateral actions which could worsen the situation, but backed down during the Security Council debate on 14 December, when Germany appeared determined to defy the UN resolution. On 17 December, the EEC formally agreed to grant Croatia diplomatic recognition on 15 January 1992, relying on opinion of the Badinter Arbitration Committee.[31] The Committee ruled that Croatia's independence should not be recognized immediately, because the new Croatian Constitution did not provide protection of minorities required by the EEC. In response, the President Franjo Tuđman gave written assurances to Robert Badinter that the deficit would be remedied.[32] The RSK formally declared its separation from Croatia on 19 December, but its statehood and independence were not recognized internationally.[33] On 26 December, Yugoslav authorities announced plans for a smaller state, which could include the territory captured from Croatia,[34] but the plan was rejected by the UN General Assembly.[35]

Croatia was first recognized as an independent state on 26 June 1991 by Slovenia, which declared its own independence on the same day as Croatia.[17] Lithuania followed on 30 July, and Ukraine, Latvia, Iceland, and Germany in December 1991.[36] The EEC countries granted Croatia recognition on 15 January 1992, and the United Nations admitted them in May 1992.[37][38]

Aftermath

[edit]Although it is not a public holiday, 15 January is marked as the day Croatia won international recognition by Croatian media and politicians.[39] On the day's 10th anniversary in 2002, the Croatian National Bank minted a 25 kuna commemorative coin.[40] In the period following the declaration of independence, the war escalated, with the sieges of Vukovar[41] and Dubrovnik,[42] and fighting elsewhere, until a ceasefire of 3 January 1992 led to stabilization and a significant reduction of violence.[43] The war effectively ended in August 1995 with a decisive victory for Croatia as a result of Operation Storm.[44] Present day borders of Croatia were established when the remaining Serb-held areas of Eastern Slavonia were restored to Croatia pursuant to the Erdut Agreement of November 1995, with the process concluded in January 1998.[45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Izviješće o provedenom referendumu" [Report on performed referendum] (PDF) (in Croatian). State Election Committee. 22 May 1991. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 February 2012. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Šute, Ivica (1 April 1999). "Deklaracija o nazivu i položaju hrvatskog književnog jezika – Građa za povijest Deklaracije, Zagreb, 1997, str. 225" [Declaration on the Status and Name of the Croatian Standard Language – Declaration History Articles, Zagreb, 1997, p. 225] (PDF). Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest (in Croatian). 31 (1): 317–318. ISSN 0353-295X. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ Vlado Vurušić (6 August 2009). "Heroina Hrvatskog proljeća" [Heroine of the Croatian Spring]. Jutarnji list (in Croatian). Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- ^ a b Rich, Roland (1993). "Recognition of States: The Collapse of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union". European Journal of International Law. 4 (1): 36–65. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035834. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- ^ Frucht 2005, p. 433.

- ^ "Leaders of a Republic in Yugoslavia Resign". The New York Times. Reuters. 12 January 1989. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Davor Pauković (1 June 2008). "Posljednji kongres Saveza komunista Jugoslavije: uzroci, tijek i posljedice raspada" [Last Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia: Causes, Consequences and Course of Dissolution] (PDF). Časopis Za Suvremenu Povijest (in Croatian). 1 (1). Centar za politološka istraživanja: 21–33. ISSN 1847-2397. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Branka Magas (13 December 1999). "Obituary: Franjo Tudjman". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- ^ "Armed Serbs Guard Highways in Croatia During Referendum". The New York Times. 20 August 1990. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Nohlen, Dieter; Stöver, Philip (2010). Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft. p. 401. ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Chuck Sudetic (2 October 1990). "Croatia's Serbs Declare Their Autonomy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. Routledge. 1998. pp. 272–278. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ a b "Odluka o raspisu referenduma" [Decision to hold a referendum]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 2 May 1991. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ "Croatia Calls for EC-Style Yugoslavia". Los Angeles Times. 16 July 1991. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (20 May 1991). "Croatia Votes for Sovereignty and Confederation". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Filipović, Vladimir (2022). "Srpska pobuna u selima vukovarske općine 1990. - 1991" [Serb Rebelion in the Villages of Vukovar Municipality 1990. - 1991.]. Scrinia Slavonica (in Croatian). 22 (1). Department for the History of Slavonia, Srijem and Baranja of the Croatian Institute of History: 291–319. doi:10.22586/ss.22.1.9. S2CID 253783796. Retrieved 4 December 2022 – via Hrčak.

- ^ a b Chuck Sudetic (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ "Deklaracija o proglašenju suverene i samostalne Republike Hrvatske" [Declaration on proclamation of sovereign and independent Republic of Croatia]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 25 June 1991. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Riding, Alan (26 June 1991). "Europeans Warn on Yugoslav Split". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (29 June 1991). "Conflict in Yugoslavia; 2 Yugoslav States Agree to Suspend Secession Process". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (6 October 1991). "Shells Still Fall on Croatian Towns Despite Truce". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ "Yugoslav Planes Attack Croatian Presidential Palace". The New York Times. 8 October 1991. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (8 October 1991). "Croatia Leader's Palace Attacked". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- ^ "Govor predsjednika Hrvatskog sabora Luke Bebića povodom Dana neovisnosti" [Speech of Luka Bebić, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament on occasion of the Independence day] (in Croatian). Sabor. 7 October 2008. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ Dražen Boroš (8 October 2011). "Dvadeset godina slobodne Hrvatske" [Twenty years of free Croatia] (in Croatian). Glas Slavonije. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Zakon o blagdanima, spomendanima i neradnim danima u Republici Hrvatskoj" [Law of Holidays, Memorial Days and Non-Working Days in the Republic of Croatia]. Narodne Novine (in Croatian). 15 November 2019. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ Sandro Knezović (February 2007). "Europska politika u vrijeme disolucije jugoslavenske federacije" [European Politics at the Time of the Dissolution of the Yugoslav Federation] (PDF). Politička Misao (in Croatian). 43 (3). University of Zagreb, Faculty of Political Sciences: 109–131. ISSN 0032-3241. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ Pellet, Allain (1992). "The Opinions of the Badinter Arbitration Committee: A Second Breath for the Self-Determination of Peoples" (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 3 (1): 178–185. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.ejil.a035802. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2011.

- ^ Kraljević, Egon (November 2007). "Prilog za povijest uprave: Komisija za razgraničenje pri Predsjedništvu Vlade Narodne Republike Hrvatske 1945.-1946" [Contribution to the history of public administration: commission for the boundary demarcation at the government's presidency of the People's Republic of Croatia, 1945–1946] (PDF). Arhivski vjesnik (in Croatian). 50 (50). Croatian State Archives: 121–130. ISSN 0570-9008. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

- ^ Čobanov, Saša; Rudolf, Davorin (2009). "Jugoslavija: unitarna država ili federacija povijesne težnje srpskoga i hrvatskog naroda – jedan od uzroka raspada Jugoslavije" [Yugoslavia: a unitary state or federation of historic efforts of Serbian and Croatian nations—one of the causes of breakup of Yugoslavia]. Zbornik radova Pravnog fakulteta u Splitu (in Croatian). 46 (2). University of Split Faculty of Law. ISSN 1847-0459. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ Lucarelli, Sonia (2000). Europe and the breakup of Yugoslavia: a political failure in search of a scholarly explanation. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 125–129. ISBN 978-90-411-1439-6. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Roland Rich (1993). "Recognition of States: The Collapse of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union" (PDF). European Journal of International Law. 4 (1): 48–49. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ^ Statehood and the law of self-determination. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. 2002. pp. 79–81. ISBN 978-90-411-1890-5. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Serb-Led Presidency Drafts Plan For New and Smaller Yugoslavia". The New York Times. 27 December 1991. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "A/RES/49/43 The situation in the occupied territories of Croatia" (PDF). United Nations. 9 February 1995. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- ^ "Date of Recognition and Establishment of Diplomatic Relation". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (Croatia). Archived from the original on 13 August 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Stephen Kinzer (24 December 1991). "Slovenia and Croatia Get Bonn's Nod". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ Paul L. Montgomery (23 May 1992). "3 Ex-Yugoslav Republics Are Accepted into U.N." The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 November 2012. Retrieved 29 July 2012.

- ^ "Obilježena obljetnica priznanja" [Recognition Anniversary Marked] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 15 January 2011. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ "Commemorative 25 Kuna Coins in Circulation". Croatian National Bank. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 29 December 2011.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (18 November 1991). "Croats Concede Danube Town's Loss". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ Binder, David (9 November 1991). "Old City Totters in Yugoslav Siege". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Sudetic, Chuck (3 January 1992). "Yugoslav Factions Agree to U.N. Plan to Halt Civil War". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ^ Dean E. Murphy (8 August 1995). "Croats Declare Victory, End Blitz". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

- ^ Chris Hedges (16 January 1998). "An Ethnic Morass Is Returned to Croatia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2010.

Sources

[edit]- Frucht, Richard C. (2005). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-800-0.