Dollar sign

| Punctuation marks | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In other scripts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The dollar sign ($ or ![]() ) is a symbol primarily used to indicate the various units of currency around the world. The symbol can interchangeably have one or two vertical strokes. Note that while the two-stroked version is visually identical to the cifrão, it is not the same symbol.

) is a symbol primarily used to indicate the various units of currency around the world. The symbol can interchangeably have one or two vertical strokes. Note that while the two-stroked version is visually identical to the cifrão, it is not the same symbol.

Origin

The sign is first attested in Spanish American, American, Canadian, Mexican and other British business correspondence in the 1770s, referring to the Spanish American peso,[1][2] also known as "Spanish dollar" or "piece of eight" in North America, which provided the model for the currency that the United States adopted in 1792 and the larger coins of the new Spanish American republics such as the Mexican peso, Peruvian eight-real and Bolivian eight-sol coins.

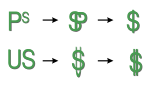

The best documented explanation holds that the sign evolved out of the Spanish and Spanish American scribal abbreviation "pˢ" for pesos. A study of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century manuscripts shows that the s gradually came to be written over the p, developing into a close equivalent to the "$" mark.[3][4][5][6][7] A variation, though less plausible, of this hypothesis derives the sign from a combination of the Greek character "psi" (ψ) and "S".[8]

Alternative origin hypotheses

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2013) |

There are a number of other hypotheses about the origin of the symbol, some with a measure of academic acceptance, others the symbolic equivalent of false etymologies.[9]

Drawn with two vertical lines

Several alternative hypotheses relate specifically to the dollar sign drawn with two vertical lines.

Spanish coat of arms

A common hypothesis holds that the sign derives from the Spanish coat of arms, which showed the Pillars of Hercules with a banner curling between them.

In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon adopted the symbol of the Pillars of Hercules and added the Latin warning Non plus ultra meaning "nothing further beyond", indicating "this is the end of the (known) world". But when Christopher Columbus came to America, the legend was changed to Plus ultra, meaning "further beyond".

The symbol was adopted by Charles V and was part of his coat of arms representing Spain's American possessions. The symbol was later stamped on coins minted in gold and silver. The also known as spanish dollar was the first global currency used in the entire world since Spanish Empire were the first global Empire. These coins, depicting the Pillars over two hemispheres and a small "S"-shaped ribbon around each, were spread throughout America, Europe and Asia. According to this, traders wrote signs that, instead of saying spanish dollar (piece of eight, real de a ocho in spanish or peso duro), had this symbol made by hand, and this in turn evolved into a simple S with two vertical bars. When USA got the independence form UK, they created the american dollar but in the first decades they still used the spanish dollar because were more popular in all markets.

From "U.S."

A dollar sign with two vertical lines could have started off as a monogram of 'USA', used on money bags issued by the United States Mint. The letters U and S superimposed resemble the historical double-stroke dollar sign ![]() : the bottom of the 'U' disappears into the bottom curve of the 'S', leaving two vertical lines. It is postulated from the papers of Dr. James Alton James, a professor of history at Northwestern University from 1897 to 1935, that the symbol with two strokes was an adapted design of the patriot Robert Morris in 1778.[10] Robert Morris was such a zealous patriot – known as the "Financier of the Revolution in the West" – that conjecture does not overstep its bounds in purporting this hypothesis as viable.[11] A similar idea claims that the letters U and S would stand for unit of silver, referencing pieces of eight again, but that is unlikely since one would expect it to be in Spanish instead.

: the bottom of the 'U' disappears into the bottom curve of the 'S', leaving two vertical lines. It is postulated from the papers of Dr. James Alton James, a professor of history at Northwestern University from 1897 to 1935, that the symbol with two strokes was an adapted design of the patriot Robert Morris in 1778.[10] Robert Morris was such a zealous patriot – known as the "Financier of the Revolution in the West" – that conjecture does not overstep its bounds in purporting this hypothesis as viable.[11] A similar idea claims that the letters U and S would stand for unit of silver, referencing pieces of eight again, but that is unlikely since one would expect it to be in Spanish instead.

German thaler

Another hypothesis is that it derives from the symbol used on a German Thaler. According to Ovason (2004), on one type of thaler one side showed a crucifix while the other showed a serpent hanging from a cross, the letters NU near the serpent's head, and on the other side of the cross the number 21. This refers to the Bible, Numbers, Chapter 21 (see Nehushtan).[citation needed].

A similar symbol, constructed by superposition of "S" and "I" or "J", was used to denote German Joachimsthaler ("S" and "J" standing for St. Joachim who gave his name to the place where the first thalers were minted). It was known in the English-speaking world by the 17th century, appearing in 1686 edition of An Introduction to Merchants' Accounts by John Collins.[12]

Later history

Robert Morris was the first to use that symbol in official documents and in official communications with Oliver Pollock. The US Dollar was directly based on the Spanish Milled Dollar when, in the Coinage Act of 1792, the first Mint Act, its value was fixed (per the U.S. Constitution, Article I, Section 8, clause 1 power of the United States Congress "To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures") as being "of the value of a Spanish milled dollar as the same is now current, and to contain three hundred and seventy-one grains and four sixteenth parts of a grain of pure, or four hundred and sixteen grains of standard silver".

According to a plaque in St Andrews, Scotland, the dollar sign was first cast into type at a foundry in Philadelphia, United States in 1797 by the Scottish immigrants John Baine, Archibald Binney and James Ronaldson.

The dollar sign did not appear on U.S. coinage until February 2007,[citation needed] when it was used on the reverse of a $1 coin authorized by the Presidential $1 Coin Act of 2005.[13]

The dollar sign appears as early as 1847 on the $100 Mexican War notes and the reverse of the 1869 $1000 United States note.[14][15] The dollar sign also appears on the reverse of the 1934 $100,000[16] note.

In Japanese and Korean, the Han character 弗 has been repurposed to represent the dollar sign due to its visual similarity.

Use in computer software

The dollar sign is one of the few symbols that are almost universally present in computer character sets but rarely needed in its literal meaning within computer software. As a result, the character has been used on computers for many purposes unrelated to money. Its uses in programming languages have often influenced or provoked its uses in operating systems, and applications.

Encoding

The dollar sign "$" has Unicode code point U+0024 (inherited from Latin-1).

- U+0024 $ DOLLAR SIGN ($)

There are no separate characters for one and two line variants. This is typeface-dependent.

There are also three other codepoints that originate from other East Asian standards: the Taiwanese small form variant, the CJK fullwidth form, and the Japanese emoji. The glyphs for these codepoints are typically larger or smaller than the primary codepoint, but the difference is mostly aesthetic or typographic, and the meanings of the symbols are the same.

However, for usage as the special character in various computing applications (see following sections), U+0024 is typically the only code that is recognized.

Programming languages

- $ was used for defining string variables in older versions of the BASIC language ("$" was often pronounced "string" instead of "dollar" in this use).

- $ is used for defining hexadecimal constants in Pascal-like languages such as Delphi, and in some variants of assembly language.

- $ is prefixed to names to define variables in the PHP language and the AutoIt automation script language, scalar variables in the Perl language (see sigil (computer programming)), and global variables in the Ruby language. In Perl programming this includes scalar elements of arrays $array[7] and hashes $hash{foo}.

- In most shell scripting languages, $ is used for interpolating environment variables, special variables, arithmetic computations and special characters, and for performing translation of localised strings.

- $ is used in the ALGOL 68 language to delimit transput format regions.

- $ is used in the TeX typesetting language to delimit mathematical regions.

- In many versions of FORTRAN 66, $ could be used as an alternative to a quotation mark for delimiting strings.

- In PL/M, $ can be used to put a visible separation between words in compound identifiers. For example, 'Some$Name' refers to the same thing as 'SomeName'.

- In Haskell, $ is used as a function application operator.

- In several JavaScript frameworks starting with Prototype.js and also popular in jQuery, $ is a common utility class, and is often referred to as the buck.

- In ASP.NET, the dollar sign used in a tag in the web page indicates an expression will follow it. The expression that follows is .NET language-agnostic, as it will work with c#, vb.net, or any CLR supported language.

- In Erlang, the dollar sign precedes character literals. The dollar sign as a character can be written $$.

- In COBOL the $ sign is used in the Picture clause to depict a floating currency symbol as the left most character. The default symbol is $ however if the CURRENCY= or CURRENCY SIGN clause is specified, any single symbol can be used.

- In some assembly languages like MIPS, the $ sign is used to represent registers.

- In Honeywell 6000 series assembler, the $ sign, when used as an address, meant the address of the instruction in which it appeared.

- In CMS-2, the $ sign is used as a statement terminator.

Operating systems

- In CP/M and subsequently in all versions of DOS (86-DOS, MS-DOS, PC DOS, more) and derivatives, $ is used as a string terminator (Int 21h with AH=09h).

- $ is used by the

promptcommand to insert special sequences into the DOS command prompt string.

- $ is used by the

- In Microsoft Windows, $ is used at the end of the share name to hide a shared folder. For example, \\server\share is accessible and visible through browsing, while \\server\share$ is accessible only by explicit reference. Most administrative shares are hidden.

- In Unix-like systems the $ is often part of the command prompt, depending on the user's shell and environment settings. For example, the default environment settings for the bash shell specify $ as part of the command prompt.

- The using history expansion

!$(same as!!1$and!-1$) means the last argument of the previous command in bash:!-2$expands to the last argument of the penultimate command,!5$expands into the last argument of the fifth command and so on. For example:

- The using history expansion

> touch my_first_file

> echo "This is my file." > !$

- where

!$expands intomy_first_file.

- where

- In the LDAP directory access protocol, $ is used as a line separator in various standard entry attributes such as postalAddress.

- In the UNIVAC EXEC 8 operating system, "$" meant "system." It was appended to entities such as the names of system files, the "sender" name in messages sent by the operator, and the default names of system-created files (like compiler output) when no specific name was specified (e.g., TPF$, NAME$, etc.)

Applications

- Microsoft Excel[17] and other spreadsheet software use the dollar sign ($) to denote an absolute cell reference.

- $ matches the end of a line or string in sed, grep, and POSIX and Perl regular expressions, and, as a result:

- $ signifies the end of a line or the file in text editors ed, ex, vi, pico and derivatives.

Currencies that use the dollar or peso sign

In addition to those countries of the world that use dollars or pesos, a number of other countries use the $ symbol to denote their currencies, including:

- Nicaraguan córdoba (usually written as C$)

- Samoan tālā (a transliteration of the word dollar)

- Tongan paʻanga

An exception is the Philippine peso, whose sign is written as ₱.

The dollar sign is also still sometimes used to represent the Malaysian ringgit (which replaced the local dollar), though its official use to represent the currency has been discontinued since 1993.

Some currencies use the cifrão (![]() ), similar to the dollar sign, but always with two strokes:

), similar to the dollar sign, but always with two strokes:

- Brazilian real

- Cape Verde escudo

- Portuguese escudo (defunct)

In Mexico and other peso-using countries, the cifrão is used as a dollar sign when a document uses pesos and dollars at the same time, to avoid confusions, but, when it used alone, usually is represented as US $ (United States dollars). Example: US $5 (five US dollars).[citation needed]

However, in Argentina, the $ sign is always used for pesos, and if they want to indicate dollars, they always write U$S 5 or US$5 (5 US dollars).

In the United States, Mexico, Australia, Argentina, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Pacific Island nations, and English-speaking Canada, the dollar or peso symbol precedes the number, unlike most currency symbols. Five dollars or pesos is written and printed as $5, whereas five cents is written as 5¢. In French-speaking Canada, the dollar symbol usually appears after the number (5$), although it sometimes appears in front of it.

Other uses

The dollar sign is also used in library cataloging to represent subsections.[citation needed]

Also, it is used derisively to indicate greed or excess money such as in "Micro$oft", "George Luca$", "Lar$ Ulrich", "Di$ney", "Chel$ea" and "GW$"; or supposed overt Americanization as in "$ky". The dollar sign is also used intentionally to stylize names such as A$AP Rocky, Ke$ha and Ty Dolla $ign or words such as ¥€$. In 1872, Ambrose Bierce referred to the California Governor as $tealand Landford.[18]

In Scrabble notation, a dollar sign is placed after a word to indicate that it is valid according to the North American word lists, but not according to the British word lists.[19]

See also

Notes

- ^ Kinnaird, Lawrence (July 1976). "The Western Fringe of Revolution". The Western Historical Quarterly. 7 (3): 259.

- ^ Popular Science (February 1930). "Origin of Dollar Sign is Traced to Mexico". Popular Science: 59. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1993) [1929]. A History of Mathematical Notations. Vol. 2. pp. 15–29.

- ^ Aiton, Arthur S.; Wheeler, Benjamin W. (May 1931). "The First American Mint". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 11 (2): 198.

- ^ Nussbaum, Arthur (1957). A History of the Dollar. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 56.

The foreign coins remained in circulation [in the United States], and the more important among them, especially the Spanish (including the Mexican) dollars, were declared by Congress on February 9, 1793, to be legal tender. The dollar sign, $, is connected with the peso, contrary to popular belief, which considers it to be an abbreviation of 'U.S.' The two parallel lines represented one of the many abbreviations of 'P,' and the 'S' indicated the plural. The abbreviation '$.' was also used for the peso, and is still used in Argentina.

- ^ Riesco Terrero, Ángel (1983). Diccionario de abreviaturas hispanas de los siglos XIII al XVIII: Con un apendice de expresiones y formulas juridico-diplomaticas de uso corriente. Salamanca: Imprenta Varona. p. 350. ISBN 84-300-9090-8.

- ^ Bureau of Engraving and Printing. "What is the origin of the $ sign?". Resources: FAQs. Retrieved 2016-04-08.

- ^ Larson, Henrietta M. (October 1939). "Note on Our Dollar Sign". Bulletin of the Business Historical Society. 13 (4): 57–58. JSTOR 3111350.

- ^ F. Cajori discusses the origins of the slash-8, the Potosi mint mark, the Pillars of Hercules, the "U.S.", the Roman sestertius, and the Boaz and Jachin hypotheses and discounts them in A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol. 2), 15–20.

- ^ James, James Alton (1970) [1937]. Robert Morris: The Life and Times of an Unknown Patriot. Freeport: Books for Libraries Press. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-8369-5527-9.

- ^ James, James Alton (1929). "'Robert Morris, Financier of the Revolution in the West'". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review.

- ^ Florence Edler de Roover. Concerning the Ancestry of the Dollar Sign. - Bulletin of the Business Historical Society. Vol. 19, No. 2 (Apr., 1945), pp. 63-64

- ^ Pub. L. No. 109-145, 119 Stat. 2664 (Dec. 22, 2005).

- ^ Cuhaj, p. 100, 321–22

- ^ Large denominations of United States currency#.241.2C000 bill

- ^ Large denominations of United States currency#.24100.2C000 bill

- ^ http://web.pdx.edu/~stipakb/CellRefs.htm

- ^ Roy Morris (1995). Ambrose Bierce: Alone in Bad Company. Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 9780195126280.

- ^ "Scrabble Glossary". Tucson Scrabble Club. Retrieved 2012-02-06.

References

- Cajori, Florian (1993). A History of Mathematical Notations. New York: Dover (reprint). ISBN 0-486-67766-4. – contains section on the history of the dollar sign, with much documentary evidence supporting the "pesos" hypothesis.

- Cuhaj, George (2009). Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money. Krause Publications, 28th Ed. ISBN 0-89689-939-X.

- Ovason, David (2004-11-30). The Secret Symbols of the Dollar Bill. Harper Paperbacks (reprint). ISBN 0-06-053045-6.