Early human migrations

−10 — – −9 — – −8 — – −7 — – −6 — – −5 — – −4 — – −3 — – −2 — – −1 — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

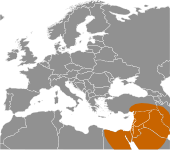

Earliest human migrations and expansions of archaic and modern humans across continents began 2 million years ago with the migration out of Africa of Homo erectus. This was followed by the migrations of other pre-modern humans including H. heidelbergensis, the likely ancestor of both anatomically modern humans and Neanderthals. Finally, the recent African origin paradigm suggests that Homo sapiens migrated out of Africa around 100,000 years ago, spread across Asia approximately 60,000 years ago, and subsequently populated other continents and islands.

Knowledge of early human migrations, a major topic of archeology, has been achieved by the study of human fossils, occasionally by stone-age artifacts and more recently has been assisted by archaeogenetics. Cultural and ethnic migrations are estimated by combining archaeogenetics and comparative linguistics.

Early humans (before Homo sapiens)

Homo erectus migrated from out of Africa via the Levantine corridor and Horn of Africa to Eurasia during the Early Pleistocene, possibly as a result of the operation of the Saharan pump, around 1.9 million years ago. They dispersed throughout most of the Old World, reaching as far as Southeast Asia. The date of original dispersal beyond Africa virtually coincides with the appearance of Homo ergaster in the fossil record, and about half a million years after the appearance of the Homo genus itself and the first stone tools of the Oldowan industry. Key sites for this early migration out of Africa are Riwat in Pakistan (~2 Ma?[1]), Ubeidiya in the Levant (1.5 Ma) and Dmanisi in the Caucasus (1.81 ± 0.03 Ma, p = 0.05[2]).

China was populated as early as 1.66 Mya based on stone artifacts found in the Nihewan Basin.[3] The archaeological site of Xihoudu (西侯渡) in Shanxi Province is the earliest recorded use of fire by Homo erectus, which is dated 1.27 million years ago.[4]

Southeast Asia (Java) was reached about 1.7 million years ago (Meganthropus). Western Europe was first populated around 1.2 million years ago (Atapuerca).[5]

Robert G. Bednarik has suggested that Homo erectus may have built rafts and sailed oceans, a theory that has raised some controversy.[6]

The expansion of H. erectus was followed by the arrival of H. antecessor in Europe around 800,000 years ago, which was in turn followed by migration from Africa to Europe of H. heidelbergensis, the likely ancestor of both modern humans and Neanderthals, around 600,000 years ago.[7] The presence of a third homo species, h. denisova (Denisovans) in Siberia (via archeological evidence) and East/South East Asia (via DNA evidence) is now well accepted. Denisovans interbred with Neanderthals and modern humans (including ancestors of Papuans, Melanesians and Australian aboriginals) as recently as 50,000ya.[8] The evolutionary ancestor of Denisovans is likely to be shared with h.sapiens and h.neandertal by way of h.heidlebergensis, though the scant archaeological evidence makes a history of Denisovans largely a matter of assumptions based on DNA data.

Neanderthal gene flow has also been observed among various populations in Africa. Additionally, among certain groups below the Sahara, there is DNA evidence of archaic admixture from hominins that broke away from the modern human lineage around 700,000 years ago. This genetic introgression has been estimated to date to 35-40,000 years before present.[9] [10] [11]

Homo sapiens migrations

Ethiopia is considered one of the earliest sites of the emergence of anatomically modern humans, Homo sapiens. The oldest of these local fossil finds, the Omo remains, were excavated in the southwestern Omo Kibish area and have been dated to the Middle Paleolithic, around 200,000 years ago.[12] Additionally, skeletons of Homo sapiens idaltu were found at a site in the Middle Awash valley. Dated to approximately 160,000 years ago, they may represent an extinct subspecies of Homo sapiens, or the immediate ancestors of anatomically modern humans.[13] Fossils excavated at the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco have since been dated to an earlier period, about 300,000 years ago.[14]

Current dating of human fossils indicates that modern humans migrating Out of Africa between 125 - 18 kya (thousand years ago) moved into lands occupied by at least four known homo species. These are (species/place/most recent date alive): h.erectus, Eurasia, 27kya; h.neanderthalensis, Europe 30kya/Central Asia 40kya; h.sp.altai (or Denisovans), Siberia/Asia/SE Asia, 30kya), h. floresiensis (or 'Hobbits', note controversy whether this is a homo species), SE Asia, 18kya. There is genetic evidence from Melanesian and Australian Aboriginal DNA, of another unidentified homo species from around 400kya to a time when interbreeding with modern humans migrating OoA could have occurred (70-30kya?). Plus, early humans could have interacted with any number of hybrid groups that became extinct, as indicated by examples such as: Lapedo Child, Europe, 24kya; Red Deer Cave People, China, 11kya; h.tsaichangensis, Taiwan, 10kya.

When modern humans reached the Near East or Levantine corridor 125,000 years ago, evidence suggests they were forced out, as their settlements were replaced by Neanderthals between 80-47kys .[8] This same reference shows support for the probability that multiple Out of Africa (OoA) migrations occurred from as early as 125kya to as far as China, but "died out" and did not contribute to the DNA of living modern humans. One well supported view is that the first modern humans that contributed to the DNA of living modern humans, spread east across Asia from Africa about 75,000 years ago across the Southern Route of Bab el Mandib connecting Ethiopia and Yemen.[15] A recent review has shown support for both the Northern Route through Sinai/Israel/Syria (Levant), and, that both routes may have been used.[8] From the Near East, some of these people went east to South Asia by 50,000 years ago, and on to Australia by 46,000 years ago at the latest,[16] when for the first time H. sapiens reached territory never reached by H. erectus. H. sapiens reached Europe around 43,000 years ago,[17] eventually replacing the Neanderthal population by 40,000 years ago [18] East Asia was reached by 30,000 years ago. Archaeological and genetic data suggest that the source populations of Paleolithic humans survived in sparsely wooded areas and dispersed through areas of high primary productivity while avoiding dense forest cover.[19] The date of migration to North America, and whether humans had previously inhabited the Americas is disputed; it may have taken place around 130 thousand years ago,[20] or considerably later, around 14 thousand years ago. The oldest radiocarbon dated carbonized plant remains were determined to be 50,300 years old and were discovered at the Topper site in Allendale South Carolina in May 2004 alongside stone tools similar to those of pre-Clovis era humans.[21] The oldest DNA evidence of human habitation in North America however, has been radiocarbon dated to 14,300 years ago, and was found in fossilized human coprolites uncovered in the Paisley Five Mile Point Caves in south-central Oregon.[22] Colonization of the Pacific islands of Polynesia began around 1300 BC, and was completed by 1280 AD (New Zealand). The ancestors of Polynesians left Taiwan around 5,200 years ago.

More recent migrations of language and culture groups within the modern species are also studied and hypothetised. The African Epipaleolithic Kebaran culture is believed to have reached Eurasia about 18,000 years ago, introducing the bow and arrow to the Middle East, and may have been responsible for the spread of the Nostratic languages. The people of the Afro-Asiatic language family seem to have reached Africa in 6,200 BC, introducing the Semitic languages to the Middle East.

From there they spread around the world. An initial venture out of Africa 125,000 years ago was followed by a flood out of Africa via the Arabian Peninsula into Eurasia around 60,000 years ago, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and one group migrating north to steppes of Central Asia.[23]

There is evidence from mitochondrial DNA that modern humans have passed through at least one genetic bottleneck, in which genome diversity was drastically reduced. Henry Harpending has proposed that humans spread from a geographically restricted area about 100,000 years ago, the passage through the geographic bottleneck and then with a dramatic growth amongst geographically dispersed populations about 50,000 years ago, beginning first in Africa and thence spreading elsewhere.[24] Climatological and geological evidence suggests evidence for the bottleneck. The explosion of Lake Toba created a 1,000 year cold period, as a result of the largest volcanic eruption of the Quaternary, potentially reducing human populations to a few tropical refugia. It has been estimated that as few as 15,000 humans survived. In such circumstances genetic drift and founder effects may have been maximised. The greater diversity amongst African genomes may be in part due to the greater prevalence of African refugia during the Toba incident.[25] However, a recent review highlights that the single-source hypothesis of non-African populations is less supported by ancient DNA analysis than multiple sources plus genetic mixing across Eurasia.[8]

Within Africa

The most recent common ancestor shared by all living human beings, dubbed Mitochondrial Eve, probably lived roughly 120–150 millennia ago,[26] the time of Homo sapiens idaltu, probably in East Africa.[citation needed]

The broad study of African genetic diversity headed by Dr. Sarah Tishkoff found the San people to express the greatest genetic diversity among the 113 distinct populations sampled, making them one of 14 "ancestral population clusters." The research also located the origin of modern human migration in south-western Africa, near the coastal border of Namibia and Angola.[27]

Around 100,000-80,000 years ago, three main lines of Homo sapiens diverged. Bearers of mitochondrial haplogroup L0 (mtDNA) / A (Y-DNA) colonized Southern Africa (the ancestors of the Khoisan ( peoples), bearers of haplogroup L1 (mtDNA) / B (Y-DNA) settled Central and West Africa (the ancestors of western pygmies), and bearers of haplogroups L2, L3, and others mtDNA remained in East Africa (the ancestors of Niger–Congo- and Nilo-Saharan-speaking peoples). (see L-mtDNA)

Exodus from Africa

There is some evidence for the argument that modern humans left Africa at least 125,000 years ago using two different routes: the Nile Valley heading to the Middle East, at least into modern Israel (Qafzeh: 120,000–100,000 years ago); and a second one through the present-day Bab-el-Mandeb Strait on the Red Sea (at that time, with a much lower sea level and narrower extension), crossing it into the Arabian Peninsula, settling in places like the present-day United Arab Emirates (125,000 years ago)[28] and Oman (106,000 years ago)[29] and then possibly going into the Indian Subcontinent (Jwalapuram: 75,000 years ago). Despite the fact that no human remains have yet been found in these three places, the apparent similarities between the stone tools found at Jebel Faya, the ones from Jwalapuram and some African ones suggest that their creators were all modern humans.[30] These findings might give some support to the claim that modern humans from Africa arrived at southern China about 100,000 years ago (Zhiren Cave, Zhirendong, Chongzuo City: 100,000 years ago;[31] and the Liujiang hominid (Liujiang County): controversially dated at 139,000–111,000 years ago [32]). Dating results of the Lunadong (Bubing Basin, Guangxi, southern China) teeth, which include a right upper second molar and a left lower second molar, indicate that the molars may be as old as 126,000 years.[33]

Since these previous exits from Africa did not leave traces in the results of genetic analyses based on the Y chromosome and on MtDNA (which represent only a small part of the human genetic material), it seems that those modern humans did not survive or survived in small numbers and were assimilated by our major antecessors. An explanation for their extinction (or small genetic imprint) may be the Toba catastrophe theory (74,000 years ago). However, some argue that its impact on human population was not dramatic.[34]

According to the Recent African Origin theory a small group of the L3 Haplogroup bearers living in East Africa migrated north east, possibly searching for food or escaping adverse conditions, crossing the Red Sea about 70 millennia ago, and in the process going on to populate the rest of the world. According to some authors, based in the fact that only descents of L3 are found outside Africa, only a few people left Africa in a single migration to a settlement in the Arabian peninsula.[35] From that settlement, some others point to the possibility of several waves of expansion close in time.

Nonetheless, in July 2017, evidence suggests that Homo sapiens may have migrated from Africa as early as 270,000 years ago, much earlier than the 70,000 years ago thought previously.[36][37]

South Asia and Australia

Dating of teeth from China provides evidence of an early migration of modern humans from Africa into Southeast Asia before 80,000 - 120,000 years ago.[38]

The later major migration from Africa traveled along the coast of Arabia and Persia to India and the rest of South Asia. Along the way H. sapiens interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans,[39] with Denisovan DNA making 0.2% of mainland Asian and Native American DNA.[40] David Reich of Harvard University and Mark Stoneking of the Planck Institute team, found genetic evidence that Denisovan ancestry is shared by Melanesians, Australian Aborigines, and smaller scattered groups of people in Southeast Asia, such as the Mamanwa, a Negrito people in the Philippines suggesting the interbreeding took place in Eastern Asia where the Denisovans lived.[41][42][43] Denisovans may have crossed the Wallace Line, with Wallacea serving as their last refugium.[44][45] Homo erectus crossed the Lombok gap reaching as far as Flores, but never made it to Australia.[46]

During this time sea level was much lower and most of Maritime Southeast Asia formed one land mass known as Sunda. Migration continued Southeast on the coastal route to the straits between Sunda and Sahul, the continental land mass of present-day Australia and New Guinea. The gaps on the Weber Line are up to 90 km wide,[47] so the migration to Australia and New Guinea would have required seafaring skills. Migration also continued along the coast eventually turning northeast to China and finally reaching Japan before turning inland. This is evidenced by the pattern of mitochondrial haplogroups descended from haplogroup M, and in Y-chromosome haplogroup C.

Sequencing of one Aboriginal genome from an old hair sample in Western Australia, revealed that the individual was descended from people who migrated into East Asia between 62,000 and 75,000 years ago. This supports the theory of a single migration into Australia and New Guinea before the arrival of Modern Asians (between 25,000 to 38,000 years ago) and their later migration into North America.[48] This migration is believed to have happened around 50,000 years ago, before Australia and New Guinea were separated by rising sea levels approximately 8,000 years ago.[49][50] This is supported by a date of 50,000 - 60,000 years ago for the oldest evidence of settlement in Australia,[16][51] around 40,000 years ago for the oldest human remains[16] The earliest humans artefacts are at least 65,000 years old[52] and the extinction Australian megafauna by humans between 46,000 and 15,000 years ago advocated by Tim Flannery,[53] which is similar to what happened in the Americas. The continued use of stone age tools in Australia has been much debated.[54]

Europe

Europe is thought to have been colonized by northwest-bound migrants from Central Asia and the Middle East, as a result of cultural adaption to big game hunting of sub-glacial steppe fauna.[55] When the first anatomically modern humans entered Europe, Neanderthals were already settled there. Debate exists whether modern human populations interbred with Neanderthal populations, most of the evidence suggesting that it happened to a small degree rather than complete absorption. Populations of modern humans and Neanderthal overlapped in various regions such as in Iberian peninsula and in the Middle East. Interbreeding may have contributed Neanderthal genes to palaeolithic and ultimately modern Eurasians and Oceanians.

An important difference between Europe and other parts of the inhabited world was the northern latitude. Archaeological evidence suggests humans, whether Neanderthal or Cro-Magnon, reached sites in Arctic Russia by 40,000 years ago.[56]

Around 20,000 BC, approximately 5,000 years after the Neanderthal extinction, the Last Glacial Maximum took place, forcing northern hemisphere inhabitants to migrate to several shelters (known as refugia) until the end of this period. The resulting populations, whether interbred with Neanderthals or not, are then presumed to have resided in those hypothetical refuges during the LGM to ultimately reoccupy Europe where archaic historical populations are considered their descendants. An alternate view is that modern European populations have descended from Neolithic populations in the Middle East that have been well documented in this area. The debate surrounding the origin of Europeans has been worded in terms of cultural diffusion versus demic diffusion.[citation needed] Archeological evidence and genetic evidence strongly support demic diffusion, that a population spread from the Middle East over the last 12,000 years.[citation needed] A scientific genetic concept called the Time to Most Recent Common Ancestor or TMRCA has been used to refute the demic diffusion in favour of cultural diffusion.[57]

Migration of the Cro-Magnons into Europe

Cro-Magnon are considered the first anatomically modern humans in Europe. They entered Eurasia by the Zagros Mountains (near present-day Iran and eastern Turkey) around 50,000 years ago, with one group rapidly settling coastal areas around the Indian Ocean and one group migrating north to steppes of Central Asia.[23] Modern human remains dating to 43-45,000 years ago have been discovered in Italy[58] and Britain,[59] with the remains found of those that reached the European Russian Arctic 40,000 years ago.[60][61]

Humans colonised the environment west of the Urals, hunting reindeer especially,[62] but were faced with adaptive challenges; winter temperatures averaged from −20 to −30 °C (−4 to −22 °F) while fuel and shelter were scarce. They travelled on foot and relied on hunting highly mobile herds for food. These challenges were overcome through technological innovations: production of tailored clothing from the pelts of fur-bearing animals; construction of shelters with hearths using bones as fuel; and digging of “ice cellars” into the permafrost for storing meat and bones.[62][63]

A mitochondrial DNA sequence of two Cro-Magnons from the Paglicci Cave in Italy, dated to 23,000 and 24,000 years old (Paglicci 52 and 12), identified the mtDNA as Haplogroup N, typical of the latter group.[64] The inland group is the founder of both North- and East Asians, Caucasoids and large sections of the Middle East population. Migration from the Black Sea area into Europe started sometime around 45,000 years ago, probably across the Bosphorus and along the Danubian corridor. By 20,000 years ago, the whole of Continental Europe had been settled.

(YBP=Years before present)

Competition with Neanderthals

The expansion of modern human population is thought to have begun 45,000 years ago, and may have taken 15,000-20,000 years for Europe to be colonized.[66][67]

During this time the Neanderthals were slowly being displaced. Because it took so long for Europe to be occupied, it appears that humans and Neanderthals may have been constantly competing for territory. The Neanderthals had larger brains, and were larger overall, with a more robust or heavily built frame, which suggests that they were physically stronger than modern Homo sapiens. Having lived in Europe for 200,000 years, they would have been better adapted to the cold weather. The anatomically modern humans known as the Cro-Magnons, with widespread trade networks, superior technology and bodies likely better suited to running, would eventually completely displace the Neanderthals, whose last refuge was in the Iberian peninsula. After about 25,000 years ago the fossil record of the Neanderthals ends, indicating that they had become extinct. The last known population lived around a cave system on the remote south-facing coast of Gibraltar from 30,000 to 24,000 years ago.

From the extent of linkage disequilibrium, it was estimated that the last Neanderthal gene flow into early ancestors of Europeans occurred 47,000–65,000 years BP. In conjunction with archaeological and fossil evidence, the gene flow is thought likely to have occurred somewhere in Western Eurasia, possibly the Middle East.[68] Studies show a higher Neanderthal admixture in East Asians than in Europeans.[69][70] North African groups share a similar excess of derived alleles with Neanderthals as do non-African populations, whereas Sub-Saharan African groups are the only modern human populations that generally did not experience Neanderthal admixture.[71] The Neanderthal-linked haplotype B006 of the dystrophin gene has also been found among nomad pastoralist groups in the Sahel and Horn of Africa, who are associated with northern populations. Consequently, the presence of this B006 haplotype on the northern and northeastern perimeter of Sub-Saharan Africa is attributed to gene flow from a non-African point of origin.[72]

Three-part origin of modern Europeans

Evidence published in 2014 from genome analysis of ancient human remains suggests that the modern native populations of Europe largely descend from three distinct lines: Hunter-gatherers who lived 45,000 years ago and most probably originated in the second human migration out of Africa into Europe, early agriculturists who moved into Europe about 9,000 years ago and mixed in, and finally a population of pontic-caspian steppe nomads who contributed DNA (and Indo-European languages) to a wide range of modern humans including native Americans.[73]

Central and Northern Asia

Mitochondrial haplogroups A, B and G originated about 50,000 years ago, and bearers subsequently colonized Siberia, Korea and Japan, by about 35,000 years ago. Parts of these populations migrated to North America.

A Paleolithic site on the Yana River, Siberia, at 71°N, lies well above the Arctic circle and dates to 27,000 radiocarbon years before present, during glacial times. This site shows that people adapted to this harsh, high-latitude, Late Pleistocene environment much earlier than previously thought.[74]

Americas

Paleo-Indians originated from Central Asia, crossing the Beringia land bridge between eastern Siberia and present-day Alaska.[75] Humans lived throughout the Americas by the end of the last glacial period, or more specifically what is known as the late glacial maximum, no earlier than 23,000 years before present.[75][76][77][78] Details of Paleo-Indian migration to and throughout the American continent, including the dates and the routes traveled, are subject to ongoing research and discussion.[79]

Dates for Paleo-Indian migration out of Beringia are a matter of current debate. Estimates range from 40,000 to around 16,500 years ago.[80][81][82]

The routes of migration are also debated. The traditional theory is that these early migrants moved when sea levels were significantly lowered due to the Quaternary glaciation,[76][79] following herds of now-extinct pleistocene megafauna along ice-free corridors that stretched between the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets.[83] Another route proposed is that, either on foot or using primitive boats, they migrated down the Pacific coast to South America as far as Chile.[84] Any archaeological evidence of coastal occupation during the last Ice Age would now have been covered by the sea level rise, up to a hundred metres since then.[85] The recent finding of Australoid genetic markers in Amazonia supports the coastal route hypothesis.[86][87]

See also

References

- ^ Out of Africa I: The First Hominin Colonization of Eurasia https://www.springer.com/social+sciences/anthropology+%26+archaeology/book/978-90-481-9035-5

- ^ Garcia, T.; Féraud, G.; Falguères, C.; de Lumley, H.; Perrenoud, C.; Lordkipanidze, D. (2010). "Earliest human remains in Eurasia: New 40Ar/39Ar dating of the Dmanisi hominid-bearing levels, Georgia". Quaternary Geochronology. 5 (4): 443–451. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2009.09.012.

- ^ R. Zhu et al. (2004), New evidence on the earliest human presence at high northern latitudes in northeast Asia.

- ^ Rixiang Zhu; Zhisheng An; Richard Pott; Kenneth A. Hoffman (June 2003). "Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans in China" (PDF). Earth Science Reviews. 61 (3–4): 191–361. Bibcode:2003ESRv...61..191A. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00110-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hopkin M (2008-03-26). "'Fossil find is oldest European yet'". Nature News. doi:10.1038/news.2008.691.

- ^ Bednarik RG (2003). "Seafaring in the Pleistocene". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 13 (1): 41–66. doi:10.1017/S0959774303000039.

ScienceNews summary - ^ Finlayson, Clive (2005). "Biogeography and evolution of the genus Homo". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 20 (8). Elsevier: 457–463. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.05.019. PMID 16701417.

- ^ a b c d Lopez, Saioa; van Dorp, Lucy; Hellenthal, Garrett (2016). "Human Dispersal Out of Africa: A Lasting Debate". Evolutionary Bioinformatics: 57. doi:10.4137/EBO.S33489. ISSN 1176-9343.

- ^ Hammer, M.F.; Woerner, A.E.; Mendez, F.L.; Watkins, J.C.; Wall, J.D. (2011). "Genetic evidence for archaic admixture in Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (37): 15123–15128. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109300108. PMC 3174671. PMID 21896735.

- ^ Callaway, E. (26 July 2012). "Hunter-gatherer genomes a trove of genetic diversity". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.11076.

- ^ Lachance, J.; Vernot, B.; Elbers, C.C.; Ferwerda, B.; Froment, A.; Bodo, J.M.; et al. (2012). "Evolutionary History and Adaptation from High-Coverage Whole-Genome Sequences of Diverse African Hunter-Gatherers". Cell. 150 (3): 457–469. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.009. PMC 3426505. PMID 22840920.

- ^ Mcdougall, I.; Brown, H.; Fleagle, G. (Feb 2005). "Stratigraphic placement and age of modern humans from Kibish, Ethiopia". Nature. 433 (7027): 733–736. Bibcode:2005Natur.433..733M. doi:10.1038/nature03258. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 15716951.

- ^ White, T. D.; Asfaw, B.; Degusta, D.; Gilbert, H.; Richards, G. D.; Suwa, G.; Clark Howell, F. (2003). "Pleistocene Homo sapiens from Middle Awash, Ethiopia". Nature. 423 (6941): 742–7. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..742W. doi:10.1038/nature01669. PMID 12802332.

- ^ Callaway, Ewan (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- ^ "Hints Of Earlier Human Exit From Africa". Science News. doi:10.1126/science.1199113. Retrieved 2011-05-01.

- ^ a b c Bowler, James M.; et al. (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia". Nature. 421 (6925): 837–840. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..837B. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511.

- ^ "Fossil Teeth Put Humans in Europe Earlier Than Thought". The New York Times. 2011-11-02.

- ^ http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/08/140820-neanderthal-dating-bones-archaeology-science/

- ^ Gavashelishvili, A.; Tarkhnishvili, D. (2016). "Biomes and human distribution during the last ice age". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 25 (5): 563–574. doi:10.1111/geb.12437.

- ^ "A 130,000-year-old archaeological site in southern California, USA". Nature. 544: 479–483. doi:10.1038/nature22065.

- ^ Science Daily, Science Daily (18 November 2004). "New Evidence Puts Man In North America 50,000 Years Ago". www.sciencedaily.com. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Staff (October 3, 2014). "Cave containing earliest human DNA dubbed historic". Phys.org. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ a b "Atlas of human journey: 45 -- 40,000". The genographic project. National Geographic Society. 1996–2010. Retrieved 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Harpending, Henry; Cochran, Gregory (2009). THE 10,000 YEAR EXPLOSION (PDF). Basic Books. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-465-00221-4. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Ambrose, Stanley (1998). "Late Pleistocene human population bottlenecks, volcanic winter, and differentiation of modern humans". Journal of Human Evolution. 34 (6): 623–651. doi:10.1006/jhev.1998.0219. PMID 9650103.

- ^ Misconceptions Around Mitochondrial Eve, Alec MacAndrew.

- ^ BBC World News "Africa's genetic secrets unlocked", 1 May 2009; the results were published in the online edition of the journal Science.

- ^ Lawler, Andrew (2011). "Did Modern Humans Travel Out of Africa Via Arabia?". Science. 331 (6016): 387. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..387L. doi:10.1126/science.331.6016.387. PMID 21273459.

- ^ Trail of 'Stone Breadcrumbs' Reveals the Identity of One of the First Human Groups to Leave Africa ScienceDaily (Nov. 30, 2011) http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2011/11/111130171049.htm

- ^ Hints of earlier human exit from Africa, http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/69197/title/Hints_of_earlier_human_exit_from_Africa

- ^ Liu, Wu; et al. (2010). "Human remains from Zhirendong, South China, and modern human emergence in East Asia". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (45): 19201–19206. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014386107. PMC 2984215. PMID 20974952. (the authors seem to accept that the individual has African recent ascentry, but with Asian archaic human admixture). See also Robin Dennell, Two interpretations of the Zhirendong mandible described by Liu and colleagues, Nature Volume: 468, 25 November 2010, pages: 512–513, doi:10.1038/468512a; Brief comments at Modern Humans Emerged Far Earlier Than Previously Thought, Fossils from China Suggest, ScienceDaily (Oct. 25, 2010) http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/10/101025172924.htm; and Oldest Modern Human Outside of Africa Found: http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/10/101025-oldest-human-fossil-china-out-of-africa-science/

- ^ Shena, Guanjun; et al. (2002). "U-Series dating of Liujiang hominid site in Guangxi, Southern China". Journal of Human Evolution. 43 (6): 817–829. doi:10.1006/jhev.2002.0601. PMID 12473485.

- ^ Lunadong fossils support theory of earlier dispersal of modern man

- ^ Balter, Michael (2010). "Of Two Minds About Toba's Impact". Science. 327 (5970): 1187–1188. Bibcode:2010Sci...327.1187B. doi:10.1126/science.327.5970.1187-a. PMID 20203021.

- ^ "Both Australian Aborigines and Europeans Rooted in Africa". News.softpedia.com. Retrieved 2011-01-11.

- ^ Zimmer, Carl (4 July 2017). "In Neanderthal DNA, Signs of a Mysterious Human Migration". New York Times. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

- ^ Posth, Cosimo; et al. (4 July 2017). "Deeply divergent archaic mitochondrial genome provides lower time boundary for African gene flow into Neanderthals". Nature Communications. doi:10.1038/ncomms16046. Retrieved 4 July 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "Teeth from China reveal early human trek out of Africa". nature.com. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- ^ Dennell, Robin; Petraglia, Michael D. (2012). "The dispersal of Homo sapiens across southern Asia: how early, how often, how complex?". Quaternary Science Reviews. 47: 15–22. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.05.002.

- ^ Prüfer, Kay; et al. (2013). "The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains". Nature. 505 (7481): 43–49. Bibcode:2014Natur.505...43P. doi:10.1038/nature12886. PMC 4031459. PMID 24352235. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (22 September 2011), "First Aboriginal genome sequenced", Nature, Nature News, doi:10.1038/news.2011.551

- ^ Reich; et al. (2011), "Denisova Admixture and the First Modern Human Dispersals into Southeast Asia and Oceania", The American Journal of Human Genetics, 89 (4): 516–28, doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.005, PMC 3188841, PMID 21944045

- ^ Choi, Charles (22 September 2011), Now-Extinct Relative Had Sex with Humans Far and Wide, LiveScience

- ^ Cooper A.; Stringer C.B. (2013), "Did the Denisovans Cross the Wallace Line", Science, 342 (6156): 321–3, doi:10.1126/science.1244869, PMID 24136958

- ^ "Humans dated ancient Denisovan relatives beyond the Wallace Line".

- ^ First Mariners – Archaeology Magazine Archive. Archive.archaeology.org. Retrieved on 2013-11-16.

- ^ "Pleistocene Sea Level Maps". Fieldmuseum.org. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Rasmussen, M; et al. (Oct 2011). "An Aboriginal Australian genome reveals separate human dispersals into Asia". Science. 334 (6052): 94–8. doi:10.1126/science.1211177. PMC 3991479. PMID 21940856.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last2=(help) - ^ Hudjashov G, Kivisild T, Underhill PA, et al. (May 2007). "Revealing the prehistoric settlement of Australia by Y chromosome and mtDNA analysis". Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104 (21): 8726–30. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8726H. doi:10.1073/pnas.0702928104. PMC 1885570. PMID 17496137.

- ^ Wade, Nicholas (2007-05-08). "From DNA Analysis, Clues to a Single Australian Migration". Australia: Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2011-05-01.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Smith, Mike; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley A.; Faulkner, Patrick; Manne, Tiina; Hayes, Elspeth; Roberts, Richard G.; Jacobs, Zenobia; Carah, Xavier; Lowe, Kelsey M.; Matthews, Jacqueline; Florin, S. Anna (June 2015). "The archaeology, chronology and stratigraphy of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II): A site in northern Australia with early occupation". Journal of Human Evolution. 83: 46–64. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.03.014. PMID 25957653.

- ^ Clarkson, Chris; Jacobs, Zenobia; Marwick, Ben; Fullagar, Richard; Wallis, Lynley; Smith, Mike; Roberts, Richard G.; Hayes, Elspeth; Lowe, Kelsey; Carah, Xavier; Florin, S. Anna; McNeil, Jessica; Cox, Delyth; Arnold, Lee J.; Hua, Quan; Huntley, Jillian; Brand, Helen E. A.; Manne, Tiina; Fairbairn, Andrew; Shulmeister, James; Lyle, Lindsey; Salinas, Makiah; Page, Mara; Connell, Kate; Park, Gayoung; Norman, Kasih; Murphy, Tessa; Pardoe, Colin (19 July 2017). "Human occupation of northern Australia by 65,000 years ago". Nature. 547 (7663): 306–310. doi:10.1038/nature22968.

- ^ Flannery, Tim (2002), "The Future Eaters: An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People" (Grove Press)

- ^ Mellars, Paul (11 August 2006). "Going East: New Genetic and Archaeological Perspectives on the Modern Human Colonization of Eurasia". Science. 313 (5788): 796–800. Bibcode:2006Sci...313..796M. doi:10.1126/science.1128402. PMID 16902130. Retrieved 3 April 2006.

- ^ Oppenheimer, Stephen "Out of Eden: Peopling of the World" (Robinson; New Ed edition (March 1, 2012))

- ^ Pavlov, Pavel; John Inge Svendsen; Svein Indrelid (Sep 6, 2001). "Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago". Nature. 413 (6851): 64–67. Bibcode:2001Natur.413...64P. doi:10.1038/35092552. PMID 11544525.

- ^ "A Comparison of Y-Chromosome Variation in Sardinia and Anatolia Is More Consistent with Cultural Rather than Demic Diffusion of Agriculture". Plosone.org. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Benazzi, S.; Douka, K.; Fornai, C.; Bauer, C. C.; Kullmer, O.; Svoboda, J. Í.; Pap, I.; Mallegni, F.; Bayle, P.; Coquerelle, M.; Condemi, S.; Ronchitelli, A.; Harvati, K.; Weber, G. W. (2011). "Early dispersal of modern humans in Europe and implications for Neanderthal behaviour". Nature. 479 (7374): 525–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..525B. doi:10.1038/nature10617. PMID 22048311.

- ^ Higham, T.; Compton, T.; Stringer, C.; Jacobi, R.; Shapiro, B.; Trinkaus, E.; Chandler, B.; Gröning, F.; Collins, C.; Hillson, S.; o’Higgins, P.; Fitzgerald, C.; Fagan, M. (2011). "The earliest evidence for anatomically modern humans in northwestern Europe". Nature. 479 (7374): 521–4. Bibcode:2011Natur.479..521H. doi:10.1038/nature10484. PMID 22048314.

- ^ Pavlov, Pavel; Svendsen, John Inge; Indrelid, Svein (2001). "Human presence in the European Arctic nearly 40,000 years ago". Nature. 413 (6851): 64–7. doi:10.1038/35092552. PMID 11544525.

- ^ "Mamontovaya Kurya:an enigmatic, nearly 40000 years old Paleolithic site in the Russian Arctic" (PDF).

- ^ a b Hoffecker, J. (2006). A Prehistory of the North: Human Settlements of the Higher Latitudes. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 101.

- ^ Hoffecker, John F. (2002). Desolate landscapes: Ice-Age settlement in Eastern Europe. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. pp. 158–162, 217–233.

- ^ Caramelli, D; Lalueza-Fox, C; Vernesi, C; Lari, M; Casoli, A; Mallegni, F; Chiarelli, B; Dupanloup, I; Bertranpetit, J; Barbujani, G; Bertorelle, G (May 2003). "Evidence for a genetic discontinuity between Neandertals and 24,000-year-old anatomically modern Europeans" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (11): 6593–7. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.6593C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1130343100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 164492. PMID 12743370.

- ^ Currat M, Excoffier L (2004). "Modern Humans Did Not Admix with Neanderthals during Their Range Expansion into Europe". PLoS Biol. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Maca-Meyer N, González AM, Larruga JM, Flores C, Cabrera VM (2001). "Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions". BMC Genet. 2 (1): 13. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. PMC 55343. PMID 11553319.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Currat M, Excoffier L (Dec 2004). "Modern humans did not admix with Neanderthals during their range expansion into Europe". PLoS Biol. 2 (12): e421. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020421. PMC 532389. PMID 15562317.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Sankararaman, S.; Patterson, N.; Li, H.; Pääbo, S.; Reich, D; Akey, J.M. (2012). "The Date of Interbreeding between Neandertals and Modern Humans". PLoS Genetics. 8 (10): e1002947. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002947. PMC 3464203. PMID 23055938.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Meyer, M.; Kircher, M.; Gansauge, M.T.; Li, H.; Racimo, F.; Mallick, S.; et al. (2012). "A High-Coverage Genome Sequence from an Archaic Denisovan Individual". Science. 338 (6104): 222–226. doi:10.1126/science.1224344. PMC 3617501. PMID 22936568.

- ^ Wall, J.D.; Yang, M.A.; Jay, F.; Kim, S.K.; Durand, E.Y.; Stevison, L.S.; et al. (2013). "Higher Levels of Neanderthal Ancestry in East Asians than in Europeans". Genetics. 194 (1): 199–209. doi:10.1534/genetics.112.148213.

- ^ Sánchez-Quinto, F.; Botigué, L.R.; Civit, S.; Arenas, C.; Ávila-Arcos, M.C.; Bustamante, C.D.; et al. (2012). "North African Populations Carry the Signature of Admixture with Neandertals". PLoS ONE. 7 (10): e47765. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047765. PMC 3474783. PMID 23082212.

We found that North African populations have a significant excess of derived alleles shared with Neandertals, when compared to sub-Saharan Africans. This excess is similar to that found in non-African humans, a fact that can be interpreted as a sign of Neandertal admixture. Furthermore, the Neandertal's genetic signal is higher in populations with a local, pre-Neolithic North African ancestry. Therefore, the detected ancient admixture is not due to recent Near Eastern or European migrations. Sub-Saharan populations are the only ones not affected by the admixture event with Neandertals.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "An X-linked haplotype of Neandertal origin is present among all non-African populations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (7): 1957–1962. 2011. Retrieved 22 July 2017.

Of 1,420 sub-Saharan chromosomes, only one copy of B006 was observed in Ethiopia, and five in Burkina Faso, one among the Rimaibe and four among the Fulani and Tuareg, nomad-pastoralists known for having contacts with northern populations (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). B006 only occurrence at the northern and northeastern outskirts of sub-Saharan Africa is thus likely to be a result of gene flow from a non-African source.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Gibbons, Ann (4 September 2014). "Three-part ancestry for Europeans". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pitulko, V. V.; Nikolsky, P. A.; Girya, E. Y.; Basilyan, A. E.; Tumskoy, V. E.; Koulakov, S. A.; Astakhov, S. N.; Pavlova, E. Y.; Anisimov, M. A. (2004). "The Yana RHS Site: Humans in the Arctic Before the Last Glacial Maximum". Science. 303 (5654): 52–6. doi:10.1126/science.1085219. PMID 14704419.

- ^ a b Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0-8129-7146-9. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ a b Fitzhugh, Drs. William; Goddard, Ives; Ousley, Steve; Owsley, Doug; Stanford., Dennis. "Paleoamerican". Smithsonian Institution Anthropology Outreach Office. Archived from the original on 2009-01-05. Retrieved 2009-01-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "A DNA Search for the First Americans Links Amazon Groups to Indigenous Australians". Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2015-08-28.

- ^ Bonatto, S. L.; Salzano, F. M. (1997). "A single and early migration for the peopling of greater America supported by mitochondrial DNA sequence data". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 94 (5): 1866–1871. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1866. PMC 20009. PMID 9050871.

- ^ a b "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on 2011-05-01. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Introduction". Government of Canada. Parks Canada. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-04-24. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

Canada's oldest known home is a cave in Yukon occupied not 12,000 years ago like the U.S. sites, but at least 20,000 years ago

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Pleistocene Archaeology of the Old Crow Flats". Vuntut National Park of Canada. 2008. Archived from the original on 2008-10-22. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

However, despite the lack of conclusive or widespread evidence, there are suggestions of human occupation in the northern Yukon about 24,000 years ago, and hints of the presence of humans in the Old Crow Basin as far back as about 40,000 years ago.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Journey of mankind". Bradshaw Foundation. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "The peopling of the Americas: Genetic ancestry influences health". Scientific American. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Jan., 1979), p2. 44: 55–69. JSTOR 279189.[dead link]

- ^ "68 Responses to "Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'"". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. Retrieved 2009-11-17.

- ^ accessed 26th October 2015 Genetic studies link indigenous peoples in the Amazon and Australasia Science Daily, July 21, 2015.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (2015). "'Ghost population' hints at long-lost migration to the Americas: Present-day Amazonians share an unexpected genetic link with Asian islanders, hinting at an ancient trek". Nature News. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.18029.

Further reading

- Jared Diamond, Guns, germs and steel. A short history of everybody for the last 13'000 years, 1997.

- Veeramah, Krishna R.; Hammer, Michael F. (4 February 2014). "The impact of whole-genome sequencing on the reconstruction of human population history". Nature Reviews Genetics. 15 (3): 149–162. doi:10.1038/nrg3625. PMID 24492235.

- Demeter F, Shackelford LL, Bacon AM, Duringer P, Westaway K, Sayavongkhamdy T, Braga J, Sichanthongtip P, Khamdalavong P, Ponche JL, et al. (2012). "Anatomically modern human in Southeast Asia (Laos)". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (36): 14375–14380. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10914375D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1208104109. PMC 3437904. PMID 22908291.