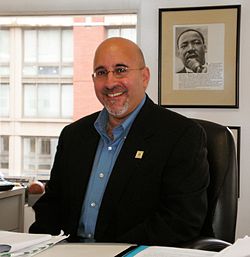

Evan Wolfson

Evan Wolfson | |

|---|---|

Evan Wolfson | |

| Born | February 4, 1957 |

| Occupation | Attorney |

Evan Wolfson (born February 4, 1957) is an attorney and gay rights advocate. He is the founder and president of Freedom to Marry, a group favoring same-sex marriage in the United States. Wolfson, who many consider to be the father and leader of the same-sex marriage movement,[1] authored the book Why Marriage Matters: America, Equality, and Gay People's Right to Marry, which Time Out New York magazine called, "Perhaps the most important gay-marriage primer ever written..."[2] He was listed as one of Time magazine's 100 Most Influential People in the World. He has taught as an adjunct professor at Columbia Law School, Rutgers Law School, and Whittier Law School and argued before the Supreme Court in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale.

Background

Wolfson was born in Brooklyn, New York and grew up in Pittsburgh. He graduated from Taylor Allderdice High School in 1974[3] and Yale College in 1978. At Yale, he was a resident of Silliman College, a history major, and Speaker of the Yale Political Union. After graduation he served in the Peace Corps in Togo, in western Africa. He returned and entered Harvard Law School, where he earned his Juris Doctor in 1983. Wolfson wrote his 1983 Harvard Law thesis on same-sex marriage, long before the question gained national prominence.[4] On October 6, 2010, he returned to the Yale Political Union to debate same-sex marriage against opponent Maggie Gallagher, chairman of the National Organization for Marriage.[5][6]

Early career

Wolfson taught political philosophy at Harvard College before he returned to his birthplace as Kings County (Brooklyn) assistant district attorney, prosecuting sex crimes and homicides, as well as serving in the Appeals Bureau. There, he wrote a Supreme Court amicus brief that helped win a nationwide ban on race discrimination in jury selection (Batson v. Kentucky). Wolfson also wrote a brief to New York's highest court, the Court of Appeals, that helped win the elimination of the marital rape exemption (People v. Liberta).[7]

Following the District Attorney’s Office, Wolfson served as Associate Counsel to Lawrence Walsh in the Office of Independent Counsel (Iran/Contra). In 1992, he served on the New York State Task Force on Sexual Harassment.[7]

Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund

From 1989 until 2001 Wolfson worked full-time at Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, a gay rights advocacy non-profit. He directed their Marriage Project and coordinated the National Freedom to Marry Coalition, the forerunner to Freedom to Marry. Wolfson co-wrote an amicus brief in Baehr v. Miike, in which the Supreme Court of Hawaii said prohibiting same-sex marriage in the state constituted discrimination, and worked on Baker v. Vermont, the Vermont Supreme Court case that led to the creation of civil unions in Vermont by the state legislature as a compromise between Wolfson's group and those objecting to same-sex marriage. Wolfson called the unions a "wonderful step forward," but not enough.[8]

Wolfson appeared before the United States Supreme Court on April 26, 2000, to argue on behalf of Scoutmaster James Dale in the landmark case Boy Scouts of America v. Dale, in which the Court ruled that the Boy Scouts organization had the right to expel Dale for revealing that he was gay through their First Amendment rights. The justices questioned Wolfson "aggressively."[9] The Court ruled 5-4 against Dale, but Wolfson, said, "Even before we change the [Boy Scout] policy, we are succeeding in getting people to rethink how they feel about gay people."[8] Dale said of Wolfson: "Evan understood the importance of the organization to me, and the importance of an American institution like the Boy Scouts discriminating against somebody and how that could impact the public dialogue and conversation."[8]

Freedom to Marry

On April 30, 2001, Wolfson left Lambda to form Freedom to Marry with a "very generous" grant from the Evelyn & Walter Haas Jr. Fund.[8] Wolfson described the breadth of his vision for the new organization: "I'm not in this just to change the law. It's about changing society. I want gay kids to grow up believing that they can get married, that they can join the Scouts, that they can choose the life they want to live." Lambda executive director Kevin Cathcart said that over twelve years Wolfson had "personified Lambda's passion and vision for equality." Kate Kendall, executive director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights, said of her experience with Wolfson at Lambda: "What I can now say is that, in the intervening years, what has been made unmistakably clear to me by the lesbians and gay men that we work with and represent, is that the denial of our right to marry exacerbates our marginalization; winning that right is the cornerstone of full justice."[8]

In 2003 Time Magazine described him as symbolic of the gay rights movement.[10] In his book Why Marriage Matters, Wolfson calls marriage "a relationship of emotional and financial interdependence between two people who make a public commitment."[11] In 2004 Time included Wolfson on its list of the "100 most influential people in the world."[10]

Wolfson said of the Washington Supreme Court's 2006 decision ruling same-sex marriage unconstitutional, "It was a splintered court. Four justices joined powerful dissents. A three-justice plurality applying the wrong standard of review—one that was undeservedly, hopelessly, and self-fulfillingly deferential—was joined by two justices in a fiery anti-gay concurrence, making up the margin of defeat."[12]

Some critics such as BeyondMarriage.org assert Wolfson and others' work is too narrowly focused on a limited marriage agenda.[13] Richard Kim, signatory and founding board member of Queers for Economic Justice, disputes Wolfson's assertion that the same-sex movement is not pushing for a traditional, heterosexual model for all gays and lesbians and creating a political schism, and as such, gravely misrepresent the consequences of their own work for the past 20 years."[14] Wolfson replied "I think if Terrence McNally, Steinem and the others were actually shown some of Richard Kim’s articles as opposed to the broad, conciliatory and coalition-building goals found in that statement, they would not endorse his articles nor his views."[15] In a New York Times review of Why Marriage Matters, author William Saletan states what he sees as flaws in Wolfson's reasoning.[11] "[His] abstract theory of equality flattens...distinction....Thus he demands protection of committed gay couples not because they resemble heterosexual couples in all relevant respects but because it's wrong to discriminate against people because of their 'differences'." Wolfson does not favor the civil union or domestic partnership approaches, because semantic differences create "a stigma of exclusion" and deny gay couples "social and other advantages."

Personal life

Wolfson and his husband Cheng He, a change-management consultant with a Ph.D. in molecular biology,[16][17] reside in New York City. They married in New York on October 15, 2011.[18]

Selected writings

- When the police are in our bedrooms, shouldn't the courts go in after them?: An update on the fight against "Sodomy" laws, (with Robert S. Mower); 21 Fordham Urban Law Journal 997 (1994).

- Crossing the Threshold: Equal Marriage Rights for Lesbians and Gay Men and the Intra-Community Critique, 21 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 567 (1994).

- The Supreme Court's Decision in Romer v. Evans and its Implications for the Defense of Marriage Act, (with Michael Melcher), 16 Quinnipiac Law Review 217 (1996).

- Symposium: The Right to Marry: Making the case to go forward: Introduction: Marriage, Equality and America: Committed Couples, Committed Lives, 13 Widener Law Journal 691 (2004).

- Why Marriage Matters; America, Equality and Gay People's Right to Marry, Simon & Schuster hardcover edition printed July 27, 2004.

- Marriage Equality and Some Lessons for the Scary Work of Winning, 14 Law & Sexuality 135 (2005).

- Where Perry Fits in the National Strategy to Win the Freedom to Marry, 37 N.Y.U. Rev. L. & Soc. Change 123 (2013).

Recognition

- Barnard Medal of Distinction (2012), Barnard College [19]

- "John Fryer Award" (2010), American Psychiatric Association[20]

- “Human Rights Hero” (2009) Human Rights Magazine (American Bar Association)[21]

- Del Martin Phyllis Lyon Marriage Equality Award[22]

- "One of the 100 most influential gay men and women in America." (2008)[23]

- "One of the 100 most influential people in the world." (2004) Time Magazine[10]

- “One of the 100 most influential lawyers in America” (2000) National Law Journal[24]

References

- ^ July 26, 2010: http://www.abanet.org/irr/hr/hrsummer2009.pdf

- ^ Simon & Schuster website with quotes from reviews.

- ^ Mervis, Scott (October 11, 2012). "Gary Graff: Rock 'n' roll observer". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ Retrieved Dec. 1, 2010. http://www.glbtq.com/social-sciences/wolfson_evan.html

- ^ Retrieved Dec. 1, 2010. http://www.advocate.com/News/Daily_News/2010/10/04/Wolfson_Gallagher_to_Debate_at_Yale/

- ^ http://www.splcenter.org/get-informed/intelligence-report/browse-all-issues/2010/winter/the-hard-liners

- ^ a b Evan Wolfson biography on the Freedom to Marry website.

- ^ a b c d e Peter Freiberg, Wolfson leaves Lambda to focus on freedom-to-marry work, March 30, 2001, Washington Blade, via Freedom to Marry's Geocities website. (archived copy at oocities.com/evanwolfson/ftm_washblade.htm

- ^ Matt Alsdorf, Supreme Court Hears Boy Scout Case, The Advocate, April 26, 2000, via Planetout.com. Archived March 17, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c John Cloud, Gay Marriage as a Civil Right of Our Times, Time Magazine, April 26, 2004, via Time.com.

- ^ a b William Saletan, The Peculiar Institution, The New York Times, September 26, 2004; Section 7, Page 9.

- ^ Evan Wolfson, [Stay in the Fight; The Court Stumbled, but the Movement for Justice Continues], The Stranger, July 27-August 2, 2006, via TheStranger.com

- ^ Press release, Beyond Same-Sex Marriage: A New Strategic Vision For All Our Families & Relationships, BeyondMarriage.org (on file with the author)

- ^ Richard Kim, The Wedding Crasher, The Nation, August 1, 2006, via TheNation.com.

- ^ Interview with Evan Wolfson, David Shankbone, Wikinews, September 30, 2007.

- ^ Kendell, Kate For Evan Wolfson, an 'I Do' Filled With 'I Did', The Advocate 13 October 2011

- ^ Schweber, Nate (October 21, 2011). "Evan Wolfson and Cheng He - Vows". The New York Times.

- ^ Schweber, Nate (October 21, 2011). "Evan Wolfson and Cheng He - Vows". The New York Times.

- ^ [1], "Evan Wolfson and President Obama to Receive Barnard Medal of Distinction," May 8, 2012

- ^ Psychiatric News, "Activist Honored for Gay Marriage Advocacy," Dec. 3, 2010

- ^ American Bar Association, Accessed Dec. 7 2010

- ^ San Francisco Sentinel, February 2008

- ^ Out 100: Evan Wolfson

- ^ Simon and Schuster "Wolfson leaves Lambda to focus on freedom-to-marry work" Accessed Dec. 7, 2010