Fairchild Air Force Base

| Fairchild Air Force Base | |

|---|---|

| Part of Air Mobility Command (AMC) | |

| Located near: Spokane, Washington | |

Boeing KC-135 assigned to Fairchild AFB | |

Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates | 47°36′54″N 117°39′20″W / 47.61500°N 117.65556°W |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1942 |

| Built by | U.S. Government |

| In use | 1942 – present |

| Garrison information | |

| Garrison | |

Airfield information | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 2,462 ft / 750 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 47°36′54″N 117°39′20″W / 47.61500°N 117.65556°W | ||||||||||

| Website | fairchild.amc.af.mil | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

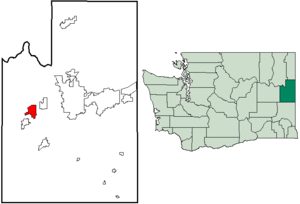

Fairchild Air Force Base (AFB) (IATA: SKA, ICAO: KSKA, FAA LID: SKA) is a United States Air Force base, located approximately 12 miles (20 km) southwest of Spokane, Washington.

The host unit at Fairchild is the 92d Air Refueling Wing (92 ARW) assigned to the Air Mobility Command's Eighteenth Air Force. The 92 ARW is responsible for providing air refueling, as well as passenger and cargo airlift and aero-medical evacuation missions supporting U.S. and coalition conventional operations as well as U.S. Strategic Command strategic deterrence missions.

Fairchild AFB was established in 1942 as the Spokane Air Depot. It is named in honor of General Muir S. Fairchild (1894–1950). A World War I aviator, he was the Vice Chief of Staff of the Air Force at the time of his death.

The 92d Air Refueling Wing is commanded by Colonel Charles "Brian" McDaniel.[1] Its Command Chief Master Sergeant is Chief Master Sergeant Christian Pugh.[2]

Overview

Fairchild is home to a wide variety of units and missions. Most prominent is its air refueling mission, with two wings, one active, the 92d Air Refueling Wing, and one national guard, the 141st Air Refueling Wing, both flying the Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker. Other units here include the Air Force Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape school, medical detachments, a weapons squadron and the Joint Personnel Recovery Agency.

Over 5,200 active duty Air Force, Air National Guard, and tenant organization military and civilian employees work on Fairchild, making the base the largest employer in Eastern Washington. Fairchild's annual economic impact on the Spokane community is approximately $427 million, constituting 13 percent of the local economy.[3]

Units

Host unit

- The 92nd OG provides air mobility for America through air refueling, airlift, and operational support.

- 92d Maintenance Group

- Provides maintenance support to world-class aircraft and equipment.

- 92d Mission Support Group

- Provides the foundation for support and morale of Fairchild.

- 92d Medical Group

Tenant units

Tenant Units at Fairchild are:[3]

- Washington Air National Guard units:

- 141st Air Refueling Wing

- 242d Combat Communications Squadron

- 256th Intelligence Squadron

- 560th Air National Guard Band of the Northwest

- 336th Training Group

- Joint Personnel Recovery Agency

- 509th Weapons Squadron

- 373rd Training Squadron, Detachment 13

- Army and Air Force Exchange Service (AAFES)

- Defense Commissary Agency (DeCA)

- Air Force Audit Agency (AFAA)

- United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE)

- Envision Store/HAZMAT

- Area Defense Council (ADC)

- Defense Security Service (DSS) Field Office

- Defense Energy Support Center (DESC)

- Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Detachment 322

- D Flight, 368th Recruiting Squadron

- Naval/Marine Corps Reserve Readiness Center

- DLA Disposition Services, formerly known as Defense Reutilization and Marketing Office (DRMO)

- Armed Forces Reserve Center

History

Fairchild AFB is named in honor of General Muir S. Fairchild (1894–1950). Born in Bellingham, he graduated from Olympia High School and attended the University of Washington in Seattle. Fairchild received his wings and commission in 1918, and served as a pilot during World War I. He held various air staff positions during World War II and received his fourth star in 1948, and died on 17 March 1950 while serving as USAF Vice Chief of Staff.

Operational history

Since 1942, Fairchild Air Force Base/Station has been a key part of the United States' defense strategy—from World War II repair depot, to Strategic Air Command bomber wing during the Cold War, to Air Mobility Command air refueling wing during Operation IRAQI FREEDOM. Today, Fairchild’s aircraft and personnel make up the backbone of the Air Force’s tanker fleet on the west coast.

Fairchild’s location, 12 miles (20 km) west of Spokane, resulted from a competition with the cities of Seattle and Everett in western Washington. The War Department chose Spokane for several reasons: better weather conditions, the location 300 miles (480 km) from the coast, and the Cascades Mountain range providing a natural barrier against possible Japanese attack.

As an added incentive to the War Department, many Spokane businesses and public-minded citizens donated money to purchase land for the base. At a cost of more than $125,000, these people bought 1,400 acres (5.7 km2) and presented the title to the War Department in January 1942. That year, the government designated $14 million to purchase more land and begin construction of a new Spokane Army Air Depot.[4]

From 1942 until 1946, the base served as a repair depot for damaged aircraft returning from the Pacific Theater. In the summer of 1946, the base was transferred to the Strategic Air Command (SAC) and assigned to the 15th Air Force (15 AF). Beginning in the summer of 1947, the 92nd and 98th Bomb Groups arrived. Both of the units flew the most advanced bomber of the day, the B-29 Superfortress. In January 1948, the base received the second of its three official names: Spokane Air Force Base.

With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, both groups deployed to Japan and Guam. After only a few months, General MacArthur released the 92nd to return to the states while the 98th remained in the Far East. The 98th was then reassigned to Nebraska. Upon its return to Fairchild, the 92nd was re-designated the 92d Bombardment Wing (Heavy). In November 1950, the base took its current name in memory of Air Force Vice Chief of Staff, General Muir S. Fairchild, a native of Bellingham. The general entered service as a sergeant with the Washington National Guard in June 1916 and was an aviator in World War I. He died at his quarters at Fort Myer while on duty in the Pentagon in March 1950. The formal dedication ceremony was held 20 July 1951, to coincide with the arrival of the wing’s first B-36 Peacemaker.[5][6]

B-52 Stratofortress and KC-135 Stratotanker

In 1956 the wing began a conversion that brought the B-52 Stratofortress to Fairchild, followed by the KC-135 Stratotanker in 1958. In 1961, the 92d became the first "aerospace" wing in the nation with the acquisition of the Atlas intercontinental ballistic missile, operated by the 567th Strategic Missile Squadron.[7][8][9][10] With the new role and the addition of missiles, the 92d Bomb Wing was re-designated the 92d Strategic Aerospace Wing. However, the designation remained longer than the missiles, as the Atlas missiles were soon obsolete and removed in 1965.[11][12]

The weapons storage area (WSA) for the bombers was located south of the runway at Deep Creek Air Force Station, a separate installation constructed from 1950 to 1953 by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and operated by the Air Materiel Command.[13] The facility was one of the thirteen original sites built for storage, maintenance, and operational readiness of the nuclear stockpile. Deep Creek became part of Fairchild AFB on 1 July 1962, with operations transferred to SAC.[14]

On 15 March 1966, the 336th Combat Crew Training Group was established at Fairchild. In 1971, the group became a wing and assumed control over all Air Force survival schools. Later reduced to a group level command, the unit, now known as the 336th Training Group, continues this mission for the Air Education and Training Command (AETC).

To provide air defense of the base, U.S. Army Nike-Hercules surface-to-air missile sites were constructed during 1956/1957. Sites were located near Cheney (F-37) 47°32′30″N 117°32′46″W / 47.54167°N 117.54611°W; Deep Creek (F-87) 47°39′29″N 117°42′55″W / 47.65806°N 117.71528°W; Medical Lake (F-45) 47°35′10″N 117°40′32″W / 47.58611°N 117.67556°W, and Spokane (F-07) 47°40′50″N 117°36′28″W / 47.68056°N 117.60778°W. The Cheney site was active between 1957 – June 1960; Deep Creek Sep 1958 – March 1966; Medical Lake 1957 – March 1966 and the Spokane site between 1957 and June 1960.

Air refueling

As military operations in Vietnam escalated in the mid-1960s, the demand for air refueling increased. Fairchild tanker crews became actively involved in Operation YOUNG TIGER, refueling combat aircraft in Southeast Asia. The wing's B-52s were not far behind, deploying to Andersen AFB on Guam for Operation Arc Light and the bombing campaign against enemy strongholds in Vietnam.

In late 1974, the Air Force announced plans to convert the 141st Fighter Interceptor Group of the Washington Air National Guard, an F-101 Voodoo unit at Geiger Field, to an air refueling mission with KC-135 aircraft. The unit would then be renamed the 141st Air Refueling Wing (141 ARW) and move to Fairchild. Work began soon thereafter and by 1976 eight KC-135E aircraft transferred to the new 141 ARW. Today, the 141 ARW continues its air mobility mission, flying the KC-135R model.

On 23 January 1987, following the inactivation of the 47th Air Division at Fairchild, the 92nd Bombardment Wing was reassigned to the 57th Air Division at Minot AFB, North Dakota.

On 13 March 1987, a KC-135A crashed into a field adjacent to the 92nd Bomb Wing headquarters and the taxiway during a practice flight for an In-Flight Refueling Demonstration planned for later that month. Seven were killed in the crash, six aboard the aircraft and one on the ground.[15][16]

Following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, a total of 560 base personnel deployed to Desert Shield and Desert Storm from August 1990 to March 1991. The 43d and 92d Air Refueling Squadrons flew a combined total of 4,004 hours, 721 sorties, and off-loaded a total of 22.5 million pounds of fuel to coalition aircraft.

On 1 September 1991, under Air Force reorganization, the 92d Bombardment Wing (Heavy) was re-designated the 92d Wing, emphasizing a dual bombing and refueling role.

In June 1992, with the inactivation of Strategic Air Command, the B-52 portion of the wing became part of the newly established Air Combat Command (ACC) and was re-designated the 92d Bomb Wing. As Strategic Air Command finished 46 years of service to the nation, Fairchild bomber and tanker crews took top honors at Proud Shield '92. This was SAC's final Bombing/Navigation Competition. The wing won the Fairchild Trophy for best bomber/tanker team as well as the Saunders Trophy for the tanker unit attaining the most points on all competition missions.

7 December 1993 marked the beginning of a significant change in the mission of Fairchild when the B-52s were transferred to another ACC base while the KC-135s, now assigned to the newly established Air Mobility Command (AMC) would remain. This was the first step in Fairchild’s transition to an air refueling wing. The departure of B-52s continued throughout the spring of 1994, with most of the bombers gone by 25 May 1994.

On 24 June 1994 one of the few remaining B-52H aircraft at Fairchild crashed during a practice flight for an upcoming air show, killing all four crew members.[17][18]

Air refueling wing

On 1 July 1994, the 92d Bomb Wing was re-designated the 92d Air Refueling Wing (92 ARW), and Fairchild AFB was transferred from ACC to Air Mobility Command (AMC) in a ceremony marking the creation of the largest air refueling wing in the Air Force. Dubbed as the new “tanker hub of the Northwest,” the wing was capable of maintaining an air bridge across the nation and the world in support of US and allied forces.

Since 1994, the 92 ARW has been involved in many contingency missions around the world. 92 ARW KC-135s have routinely supported special airlift missions in response to world events or international treaty compliance requirements.

In 1995 aircraft from Fairchild flew to Travis AFB, California in support of its first Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) mission, transporting Russian inspectors to sites in the Western U.S. The wing has flown START missions in the U.S. every year since. And in May 2000, the wing became the first active duty KC-135 unit to transport U.S. inspectors on a START mission into Ulan Ude, Russia.

Throughout much of the 1990s, the wing was actively involved in missions against Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. The wing also deployed aircraft and personnel in 1999 to support Operation Allied Force.

Following the destruction of the World Trade Center, the wing began providing around-the-clock air refueling of Combat Air Patrol fighter aircraft and initiated 24-hour ground alert operations in support of Operation Noble Eagle. The wing also began a series of extended Operation Enduring Freedom deployments for aircrews and maintainers as well as combat support and medical personnel.

1994 shooting incident

On 20 June 1994, Dean Mellberg, an ex-Air Force member, entered the base hospital and shot and killed four people and wounded 23 others.[19] Mellberg recently had been discharged from Cannon AFB, NM as unfit for duty.

Previously, psychologists Major Thomas Brigham and Captain Alan London at Fairchild AFB had found him unfit for duty, which resulted in a transfer to the Wilford Hall Medical Center at Lackland AFB for further psychological examination.[20] With Congressional pressure brought by Mellberg's mother, Airman Mellberg was found to be fit for military service. Airman Mellberg then was reassigned to Cannon Air Force Base where similar events led to him being returned to psychologists for evaluation. After this evaluation, he was discharged from Cannon AFB as being unfit for military service; he was diagnosed with mild autism.[21] He traveled to the town of Airway Heights, just outside Fairchild AFB, where he purchased weapons and planned his attack on the base.

At the time of the shooting, Fairchild's hospital was an ungated facility. The gunman, armed with a Chinese-made MAK-90, an AK-47 clone,[22] entered the office of Brigham and London and killed both men. Mellberg continued to move through the hospital, injuring several people, and killing 8-year-old Christin McCarron. The gunman then walked out of the building into the parking lot and killed Anita Lindner. He then was confronted by a security policeman, Senior Airman Andy Brown. From approximately 70 yards away, Brown ordered Mellberg to drop his weapon. After Mellberg refused, Brown fired four shots from his 9mm pistol, with two rounds hitting the perpetrator in the head and shoulder, killing him.[23] After an investigation it was concluded that Airman Brown was justified in his actions, probably having saved lives, and was awarded the Airman's Medal by then-President Bill Clinton.

Previous names

- Established as Galena Field (popular designation), renamed Spokane Air Depot, 1 March 1942

- Spokane Army Airfield, 9 July 1942

- Spokane Air Force Base, 13 January 1948

- Fairchild Air Force Base, 1 November 1950

Major commands to which assigned

- Air Service Command, 1 March 1942

- AAF Materiel and Services, 17 July 1944

- Redesignated: AAF Technical Service Command, 31 August 1944

- Redesignated: Air Technical Service Command, 1 July 1945

- Redesignated: Air Materiel Command, 9 March 1946

- Strategic Air Command, 1 September 1947

- Air Combat Command, 1 June 1992

- Air Mobility Command, 1 July 1994 – present

Base operating units

|

|

Major units assigned

|

|

References for history introduction, major commands and major units[24]

Major Aircraft and Missiles assigned

|

|

Reference[25]

Intercontinental ballistic missile facilities

The 567th Strategic Missile Squadron operated nine SM-65E Atlas ICBM sites (1 April 1960 – 25 June 1965).

- 567–1, 3.4 mi ENE of Deer Park, WA 47°58′30″N 117°24′32″W / 47.97500°N 117.40889°W

- 567–2, 3.1 mi SE of Newman Lake, WA 47°44′25″N 117°03′38″W / 47.74028°N 117.06056°W

- 567–3, 5.3 mi ESE of Rockford, WA 47°26′13″N 117°01′06″W / 47.43694°N 117.01833°W

- 567–4, 4.0 mi NE of Sprague, WA 47°19′58″N 117°54′11″W / 47.33278°N 117.90306°W

- 567–5, 0.7 mi NW of Lamona, WA 47°22′04″N 118°29′27″W / 47.36778°N 118.49083°W

- 567–6, 6.5 mi S of Davenport, WA 47°33′36″N 118°09′34″W / 47.56000°N 118.15944°W

- 567–7, 4.4 mi E of Wilbur, WA 47°45′52″N 118°36′31″W / 47.76444°N 118.60861°W

- 567–8, 6.2 mi SW of Deer Meadows, WA 47°49′40″N 118°13′21″W / 47.82778°N 118.22250°W

- 567–9, 8.9 mi NNE of Reardan, WA 47°47′42″N 117°49′51″W / 47.79500°N 117.83083°W

On 14 July 1958, the Army Corps of Engineers Northern Pacific Division directed its Seattle District to begin survey and mapping operations for the first Atlas-E site to be located in the vicinity of Spokane. Originally, the Air Force wanted three sites with three missiles at each (3 x 3); however, in early 1959, the Air Force opted to disperse the missiles to nine individual sites as a defensive safety measure. Work started at Site A on 12 May 1959, and completion at Site I occurred on 10 February 1961. Auxiliary support facilities for each site were built concurrent with the launchers.[7][8][9][10] Support facilities at Fairchild AFB, including a liquid oxygen plant, were completed by January 1961.

Activation of the 567th Strategic Missile Squadron on 1 April 1960, marked the first time SAC activated an E series Atlas unit. On 3 December 1960, the first Atlas E missile arrived at the 567th SMS. Construction continued and SAC accepted the first Series E Atlas complex on 29 July 1961. Operational readiness training, which previously had been conducted only at Vandenberg AFB, California, began at Fairchild during the following month. On 28 September 1961, Headquarters SAC declared the squadron operational and during the following month, the 567th placed the first Atlas E missile on alert status. The bulk of the Fairchild force was on alert status in November.

As a result of Defense Secretary Robert McNamara's May 1964 directive accelerating the phaseout of Atlas and Titan I ICBMs, the first Atlas missiles came off line at Fairchild in January 1965. On 31 March, the last missile came off alert status, which marked the completion of Atlas phaseout. The squadron was inactivated within 3 months.[11][12]

Today all of the former missile sites still exist and most appear to be in good condition. Most of them are in agricultural areas and presumably are being used to support farmers by storage of equipment and other material. Site "1" and "2" appear to be redeveloped into light industrial estates; "4" and "6" appear to be converted into private residences.

Weaponry

At one time, Washington state had the distinction of having more nuclear warheads than four of the six known nuclear-armed nations. These warheads were concentrated in two places: at Fairchild AFB and at the Kitsap Submarine Base across Puget Sound, on the Hood Canal. At Fairchild, 85 nuclear gravity bombs (25 B61-7 gravity bombs and 60 B83 gravity bombs) were stored in a reserve nuclear depot. Bangor's eight submarines have 24 Trident I missiles per boat with eight warheads per missile, for a total of 1,536.[26] These bombs were removed from the base by the end of the 1990s. In one instance of nuclear warhead transportation in the mid 1980s, while loading it into an airplane, one of the warheads slipped off the loader and landed onto the runway. Luckily, the warhead was not armed, so it did not detonate. North Dakota had a similar nuclear strength during the Cold War, with both SAC bases at Minot and Grand Forks equipped with B-52 bombers and Minuteman missiles. Grand Forks relinquished its nuclear role, but Minot continues.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP has a total area of 6.5 square miles (16.8 km²), all of it land. Spokane International Airport is located just four miles to the east.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 6,754 | — | |

| 1980 | 5,353 | −20.7% | |

| 1990 | 4,854 | −9.3% | |

| 2000 | 4,357 | −10.2% | |

| 2010 | 2,776 | −36.3% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census [27][28][29] | |||

As of the census[30] of 2010, there were 2,736 people. At the 2000 census there were, 1,071 households, and 1,048 families residing in the CDP. The population density was 670.2 people per square mile (258.8/km²). There were 1,114 housing units at an average density of 171.3/sq mi (66.2/km²). The racial makeup of the CDP was 78.20% White, 7.90% African American, 0.53% Native American, 3.56% Asian, 0.37% Pacific Islander, 3.79% from other races, and 5.67% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.52% of the population.

There were 1,071 households out of which 72.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 90.8% were married couples living together, 4.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 2.1% were non-families. 1.9% of all households were made up of individuals and none had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.36 and the average family size was 3.39.

In the CDP the population was spread out with 34.1% under the age of 18, 24.9% from 18 to 24, 38.3% from 25 to 44, 2.1% from 45 to 64, and 0.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 23 years. For every 100 females there were 127.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 135.7 males.

The median income for a household in the CDP was $33,512, and the median income for a family was $33,398. Males had a median income of $22,299 versus $15,815 for females. The per capita income for the CDP was $11,961. About 4.8% of families and 5.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.4% of those under age 18 and none of those age 65 or over.

Public schools

The base housing area at Fairchild is within the Medical Lake School District (#326).[31] An elementary school (K-5) is on base, renamed for Space Shuttle astronaut Michael Anderson. Students in middle school (6–8) and high school (9–12) attend classes in the city of Medical Lake, a few miles to the south. Significantly smaller than the public high schools in Spokane,[32] Medical Lake High School competes in WIAA Class 1A in athletics in the Northeast 'A' League (NEA).

See also

References

- ^ "Biographies : Colonel Charles B. Mcdaniel". Fairchild.af.mil. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Biographies : Chief Master Sgt. Christian M. Pugh". Fairchild.af.mil. 1 August 2007. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Team Fairchild". 92nd Air Refueling Wing Public Affairs. 13 January 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2012.

- ^ Dullenty, Jim (14 January 1969). "Fairchild's "birthday" confusing". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 24.

- ^ "Top air officers here for Fairchild's dedication". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 20 July 1951. p. 1.

- ^ "Rite at Fairchild draws big crowd". Spokesman-Review. 21 July 1950. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Missile fortress takes shape at Deer Park". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 27 January 1960. p. 12.

- ^ a b Petty, Robert W. (12 April 1960). "Missile sites take shape". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 8.

- ^ a b "Spokane area missile sites near completion". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 9 December 1960. p. 12.

- ^ a b "Atlas gear tested". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 5 January 1961. p. 3.

- ^ a b Petty, Robert W. (1 July 1965). "Atlas missile era is ended". Spokane Daily Chronicle. p. 1.

- ^ a b "Last Atlas sites sold for salvage". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 31 May 1967. p. b3.

- ^ Arkin, William; Norris, Robert; Handler, Joshua (1998). Taking Stock: Worldwide Nuclear Deployments 1998. Washington, D.C.: Natural Resources Defense Council. p. 71. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ "Shift Planned at Deep Creek". Spokane Daily Chronicle. 10 May 1962. Retrieved 26 May 2013.

- ^ Carrollo, Russell (14 March 1987). "KC-135 crashes at Fairchild". Spokesman-Review. p. 1.

- ^ "Other Fairchild plane crashes". Spokesman-Review. 25 June 1994. p. A6.

- ^ Check-Six (2007). "The Crash of 'Czar 52'". Check-Six.com. Retrieved 20 April 2007. – Contains video footage of the 1994 crash, and details on the hospital shootings.

- ^ "B-52 crash kills 4". Spokesman-Review. 25 June 1994. p. 1.

- ^ Camden, Jim (13 August 1994). "Error kept Fairchild gunman in uniform Investigation may lead to changes in procedure". The Spokesman-Review. via HighBeam (subscription required).

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Associated Press (22 May 1995). "Psychiatrist's Widow Hopes For Change". The Columbian. via HighBeam (subscription required).

Brigham and London believed Mellberg was unfit for military service and sent him to Wilford Hall, the Air Force's main medical center in San Antonio.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Camden, Jim (21 May 1995). "Fighting Anger, Seeking Answers Fairchild Shootings Leave Wife Of Slain Psychiatrist Campaigning For Change". The Spokesman-Review.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "An Airman's Revenge: 5 Minutes of Terror". The New York Times. 22 June 1994.

- ^ http://www.kxly920.com/Global/story.asp?S=8368881[dead link]

- ^ Mueller, Robert (1989). Volume 1: Active Air Force Bases Within the United States of America on 17 September 1982. USAF Reference Series, Office of Air Force History, United States Air Force, Washington, D.C. ISBN 0-912799-53-6, ISBN 0-16-002261-4

- ^ 92d ARW AFHRA

- ^ [1] Archived 6 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Census 2010: Fairchild AFB CDP". Spokesman.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "99011 Fairchild AFB". State of Washington, Office of Financial Management. 1990. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Washington: population of county subdivisions, 1960 to 1980" (PDF). U.S. Census. 1980. pp. 49–12. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Boundary Map". Medical Lake School District. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ "Fairchild AFB: schools". DOD Housing Network. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

Other sources

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Fairchild Air Force Base

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Fairchild Air Force Base- Maurer, Maurer. Air Force Combat Units of World War II. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office 1961 (republished 1983, Office of Air Force History, ISBN 0-912799-02-1).

- Ravenstein, Charles A. Air Force Combat Wings Lineage and Honors Histories 1947–1977. Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama: Office of Air Force History 1984. ISBN 0-912799-12-9.

- Mueller, Robert, Air Force Bases Volume I, Active Air Force Bases Within the United States of America on 17 September 1982, Office of Air Force History, 1989

External links

- Fairchild Air Force Base, official site

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective October 31, 2024

- FAA Terminal Procedures for SKA, effective October 31, 2024

- Resources for this U.S. military airport:

- FAA airport information for SKA

- AirNav airport information for KSKA

- ASN accident history for SKA

- NOAA/NWS latest weather observations

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KSKA

- Use dmy dates from March 2013

- 1942 establishments in Washington (state)

- Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces in Washington (state)

- Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces Technical Service Command

- Bases of the United States Air Force

- Buildings and structures in Spokane County, Washington

- Census-designated places in Washington (state)

- Installations of the United States Air National Guard

- Initial United States Air Force installations

- Military facilities in Washington (state)

- Military Superfund sites

- Murder in Washington (state)

- Populated places in Spokane County, Washington

- Strategic Air Command military installations

- Superfund sites in Washington (state)

- Crimes in Washington (state)