Fatty acid

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

| Components |

| Manufactured fats |

In chemistry, particularly in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with a long aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, from 4 to 28.[1] Fatty acids are usually derived from triglycerides or phospholipids. Fatty acids are important sources of fuel because, when metabolized, they yield large quantities of ATP. Many cell types can use either glucose or fatty acids for this purpose. Long-chain fatty acids cannot cross the blood–brain barrier and so cannot be used as fuel by the cells of the central nervous system; but medium-chain fatty acids octanoic acid and heptanoic acid can be used,[2] in addition to glucose and ketone bodies.

Types of fatty acids

Fatty acids that have carbon–carbon double bonds are known as unsaturated. Fatty acids without double bonds are known as saturated. They differ in length as well.

Length of free fatty acid chains

Fatty acid chains differ by length, often categorized as short to very long.

- Short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of fewer than six carbons (e.g. butyric acid).[3]

- Medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails of 6–12[4] carbons, which can form medium-chain triglycerides.

- Long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails 13 to 21 carbons.[5]

- Very long chain fatty acids (VLCFA) are fatty acids with aliphatic tails longer than 22 carbons.

Unsaturated fatty acids

Unsaturated fatty acids have one or more double bonds between carbon atoms. (Pairs of carbon atoms connected by double bonds can be saturated by adding hydrogen atoms to them, converting the double bonds to single bonds. Therefore, the double bonds are called unsaturated.)

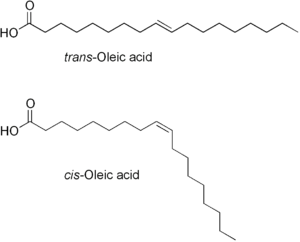

The two carbon atoms in the chain that are bound next to either side of the double bond can occur in a cis or trans configuration.

- cis

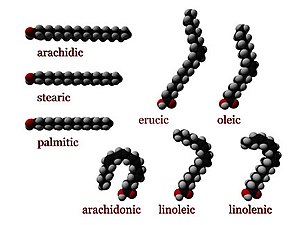

- A cis configuration means that the two hydrogen atoms adjacent to the double bond stick out on the same side of the chain. The rigidity of the double bond freezes its conformation and, in the case of the cis isomer, causes the chain to bend and restricts the conformational freedom of the fatty acid. The more double bonds the chain has in the cis configuration, the less flexibility it has. When a chain has many cis bonds, it becomes quite curved in its most accessible conformations. For example, oleic acid, with one double bond, has a "kink" in it, whereas linoleic acid, with two double bonds, has a more pronounced bend. Alpha-linolenic acid, with three double bonds, favors a hooked shape. The effect of this is that, in restricted environments, such as when fatty acids are part of a phospholipid in a lipid bilayer, or triglycerides in lipid droplets, cis bonds limit the ability of fatty acids to be closely packed, and therefore can affect the melting temperature of the membrane or of the fat.

- trans

- A trans configuration, by contrast, means that the adjacent two hydrogen atoms lie on opposite sides of the chain. As a result, they do not cause the chain to bend much, and their shape is similar to straight saturated fatty acids.

In most naturally occurring unsaturated fatty acids, each double bond has three n carbon atoms after it, for some n, and all are cis bonds. Most fatty acids in the trans configuration (trans fats) are not found in nature and are the result of human processing (e.g., hydrogenation).

The differences in geometry between the various types of unsaturated fatty acids, as well as between saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, play an important role in biological processes, and in the construction of biological structures (such as cell membranes).

| Common name | Chemical structure | Δx | C:D | n−x |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myristoleic acid | CH3(CH2)3CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 14:1 | n−5 |

| Palmitoleic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 16:1 | n−7 |

| Sapienic acid | CH3(CH2)8CH=CH(CH2)4COOH | cis-Δ6 | 16:1 | n−10 |

| Oleic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis-Δ9 | 18:1 | n−9 |

| Elaidic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | trans-Δ9 | 18:1 | n−9 |

| Vaccenic acid | CH3(CH2)5CH=CH(CH2)9COOH | trans-Δ11 | 18:1 | n−7 |

| Linoleic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12 | 18:2 | n−6 |

| Linoelaidic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | trans,trans-Δ9,Δ12 | 18:2 | n−6 |

| α-Linolenic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)7COOH | cis,cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12,Δ15 | 18:3 | n−3 |

| Arachidonic acid | CH3(CH2)4CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)3COOHNIST | cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ5Δ8,Δ11,Δ14 | 20:4 | n−6 |

| Eicosapentaenoic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)3COOH | cis,cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ5,Δ8,Δ11,Δ14,Δ17 | 20:5 | n−3 |

| Erucic acid | CH3(CH2)7CH=CH(CH2)11COOH | cis-Δ13 | 22:1 | n−9 |

| Docosahexaenoic acid | CH3CH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CHCH2CH=CH(CH2)2COOH | cis,cis,cis,cis,cis,cis-Δ4,Δ7,Δ10,Δ13,Δ16,Δ19 | 22:6 | n−3 |

Essential fatty acids

Fatty acids that are required by the human body but cannot be made in sufficient quantity from other substrates, and therefore must be obtained from food, are called essential fatty acids. There are two series of essential fatty acids: one has a double bond three carbon atoms removed from the methyl end; the other has a double bond six carbon atoms removed from the methyl end. Humans lack the ability to introduce double bonds in fatty acids beyond carbons 9 and 10, as counted from the carboxylic acid side.[6] Two essential fatty acids are linoleic acid (LA) and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). They are widely distributed in plant oils. The human body has a limited ability to convert ALA into the longer-chain omega-3 fatty acids — eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which can also be obtained from fish.

Saturated fatty acids

Saturated fatty acids have no double bonds. Thus, saturated fatty acids are saturated with hydrogen (since double bonds reduce the number of hydrogens on each carbon). Because saturated fatty acids have only single bonds, each carbon atom within the chain has 2 hydrogen atoms (except for the omega carbon at the end that has 3 hydrogens).

| Common name | Chemical structure | C:D |

|---|---|---|

| Caprylic acid | CH3(CH2)6COOH | 8:0 |

| Capric acid | CH3(CH2)8COOH | 10:0 |

| Lauric acid | CH3(CH2)10COOH | 12:0 |

| Myristic acid | CH3(CH2)12COOH | 14:0 |

| Palmitic acid | CH3(CH2)14COOH | 16:0 |

| Stearic acid | CH3(CH2)16COOH | 18:0 |

| Arachidic acid | CH3(CH2)18COOH | 20:0 |

| Behenic acid | CH3(CH2)20COOH | 22:0 |

| Lignoceric acid | CH3(CH2)22COOH | 24:0 |

| Cerotic acid | CH3(CH2)24COOH | 26:0 |

Nomenclature

Numbering of the carbon atoms in a fatty acid

The position of the carbon atoms in a fatty acid can be indicated from the COOH- (or carboxy) end, or from the -CH3 (or methyl) end. If indicated from the -COOH end, then the C-1, C-2, C-3, ….(etc.) notation is used (blue numerals in the diagram on the right, where C-1 is the –COOH carbon). If the position is counted from the other, -CH3, end then the position is indicated by the ω-n notation (numerals in red, where ω-1 refers to the methyl carbon).

The positions of the double bonds in a fatty acid chain can, therefore, be indicated in two ways, using the C-n or the ω-n notation. Thus, in an 18 carbon fatty acid, a double bond between C-12 (or ω-7) and C-13 (or ω-6) is reported either as Δ12 if counted from the –COOH end (indicating only the “beginning” of the double bond), or as ω-6 (or omega-6) if counting from the -CH3 end. The “Δ” is the Greek letter “delta”, which translates into “D” ( for Double bond) in the Roman alphabet. Omega (ω) is the last letter in the Greek alphabet, and is therefore used to indicate the “last” carbon atom in the fatty acid chain. Since the ω-n notation is used almost exclusively to indicate the positions of the double bonds close to the -CH3 end in essential fatty acids, there is no necessity for an equivalent “Δ”-like notation - the use of the ”ω-n” notation always refers to the position of a double bond.

Fatty acids with an odd number of carbon atoms are called odd-chain fatty acids, whereas the rest are even-chain fatty acids. The difference is relevant to gluconeogenesis.

Naming of fatty acids

The following table describes the most common systems of naming fatty acids.

| System | Example | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Trivial nomenclature | Palmitoleic acid | Trivial names (or common names) are non-systematic historical names, which are the most frequent naming system used in literature. Most common fatty acids have trivial names in addition to their systematic names (see below). These names frequently do not follow any pattern, but they are concise and often unambiguous. |

| Systematic nomenclature | (9Z)-octadecenoic acid | Systematic names (or IUPAC names) derive from the standard IUPAC Rules for the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry, published in 1979,[7] along with a recommendation published specifically for lipids in 1977.[8] Counting begins from the carboxylic acid end. Double bonds are labelled with cis-/trans- notation or E-/Z- notation, where appropriate. This notation is generally more verbose than common nomenclature, but has the advantage of being more technically clear and descriptive. |

| Δx nomenclature | cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12 octadecadienoic acid | In Δx (or delta-x) nomenclature, each double bond is indicated by Δx, where the double bond is located on the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from the carboxylic acid end. Each double bond is preceded by a cis- or trans- prefix, indicating the configuration of the molecule around the bond. For example, linoleic acid is designated "cis-Δ9, cis-Δ12 octadecadienoic acid". This nomenclature has the advantage of being less verbose than systematic nomenclature, but is no more technically clear or descriptive. |

| n−x nomenclature | n−3 | n−x (n minus x; also ω−x or omega-x) nomenclature both provides names for individual compounds and classifies them by their likely biosynthetic properties in animals. A double bond is located on the xth carbon–carbon bond, counting from the terminal methyl carbon (designated as n or ω) toward the carbonyl carbon. For example, α-Linolenic acid is classified as a n−3 or omega-3 fatty acid, and so it is likely to share a biosynthetic pathway with other compounds of this type. The ω−x, omega-x, or "omega" notation is common in popular nutritional literature, but IUPAC has deprecated it in favor of n−x notation in technical documents.[7] The most commonly researched fatty acid biosynthetic pathways are n−3 and n−6. |

| Lipid numbers | 18:3 18:3ω6 18:3, cis,cis,cis-Δ9,Δ12,Δ15 |

Lipid numbers take the form C:D, where C is the number of carbon atoms in the fatty acid and D is the number of double bonds in the fatty acid (if more than one, the double bonds are assumed to be interrupted by CH 2 units, i.e., at intervals of 3 carbon atoms along the chain). This notation can be ambiguous, as some different fatty acids can have the same numbers. Consequently, when ambiguity exists this notation is usually paired with either a Δx or n−x term.[7] |

Esterified, free, unsaturated, conjugated

When fatty acids circulating in the plasma (plasma fatty acids) are not in their glycerol ester form (glycerides), they are known as free fatty acids. The term can be viewed as a misnomer because they are transported complexed with a transport protein, such as albumin, as opposed to being unattached to any other molecule.[9] But the term conveys the idea that they are circulating and available for metabolism.

Fatty acids can exist in various states of saturation. Unsaturated fatty acids include monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). Conjugated fatty acids are a subset of PUFAs.

Production

Industrial

Fatty acids are usually produced industrially by the hydrolysis of triglycerides, with the removal of glycerol (see oleochemicals). Phospholipids represent another source. Some fatty acids are produced synthetically by hydrocarboxylation of alkenes.

By animals

In animals, fatty acids are formed from carbohydrates predominantly in the liver, adipose tissue, and the mammary glands during lactation.[10]

Carbohydrates are converted into pyruvate by glycolysis as the first important step in the conversion of carbohydrates into fatty acids.[10] Pyruvate is then dehydrogenated to form acetyl-CoA in the mitochondrion. However, this acetyl CoA needs to be transported into cytosol where the synthesis of fatty acids occurs. This cannot occur directly. To obtain cytosolic acetyl-CoA, citrate (produced by the condensation of acetyl-CoA with oxaloacetate) is removed from the citric acid cycle and carried across the inner mitochondrial membrane into the cytosol.[10] There it is cleaved by ATP citrate lyase into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate. The oxaloacetate is returned to mitochondrion as malate.[11] The cytosolic acetyl-CoA is carboxylated by acetyl CoA carboxylase into malonyl-CoA, the first committed step in the synthesis of fatty acids.[11][12]

Malonyl-CoA is then involved in a repeating series of reactions that lengthens the growing fatty acid chain by two carbons at a time. Almost all natural fatty acids, therefore, have even numbers of carbon atoms. When synthesis is complete the free fatty acids are nearly always combined with glycerol (three fatty acids to one glycerol molecule) to form triglycerides, the main storage form of fatty acids, and thus of energy in animals. However, fatty acids are also important components of the phospholipids that form the phospholipid bilayers out of which all the membranes of the cell are constructed (the cell wall, and the membranes that enclose all the organelles within the cells, such as the nucleus, the mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi apparatus).[10]

The "uncombined fatty acids" or "free fatty acids" found in the circulation of animals come from the breakdown (or lipolysis) of stored triglycerides.[10][13] Because they are insoluble in water, these fatty acids are transported bound to plasma albumin. The levels of "free fatty acids" in the blood are limited by the availability of albumin binding sites. They can be taken up from the blood by all cells that have mitochondria (with the exception of the cells of the central nervous system). Fatty acids can only be broken down to CO2 and water in mitochondria, by means of beta-oxidation, followed by further combustion in the citric acid cycle. Cells in the central nervous system, which, although they possess mitochondria, cannot take free fatty acids up from the blood, as the blood-brain barrier is impervious to fatty acids. These cells have to manufacture their own fatty acids from carbohydrates, as described above, in order to produce and maintain the phospholipids of their cell membranes, and those of their organelles.[10]

Fatty acids in dietary fats

The following table gives the fatty acid, vitamin E and cholesterol composition of some common dietary fats.[14] [15]

| Saturated | Monounsaturated | Polyunsaturated | Cholesterol | Vitamin E | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/100g | g/100g | g/100g | mg/100g | mg/100g | |

| Animal fats | |||||

| Lard[16] | 40.8 | 43.8 | 9.6 | 93 | 0.60 |

| Duck fat[16] | 33.2 | 49.3 | 12.9 | 100 | 2.70 |

| Butter | 54.0 | 19.8 | 2.6 | 230 | 2.00 |

| Vegetable fats | |||||

| Coconut oil | 85.2 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 0 | .66 |

| Cocoa butter | 60.0 | 32.9 | 3.0 | 0 | 1.8 |

| Palm kernel oil | 81.5 | 11.4 | 1.6 | 0 | 3.80 |

| Palm oil | 45.3 | 41.6 | 8.3 | 0 | 33.12 |

| Cottonseed oil | 25.5 | 21.3 | 48.1 | 0 | 42.77 |

| Wheat germ oil | 18.8 | 15.9 | 60.7 | 0 | 136.65 |

| Soybean oil | 14.5 | 23.2 | 56.5 | 0 | 16.29 |

| Olive oil | 14.0 | 69.7 | 11.2 | 0 | 5.10 |

| Corn oil | 12.7 | 24.7 | 57.8 | 0 | 17.24 |

| Sunflower oil | 11.9 | 20.2 | 63.0 | 0 | 49.00 |

| Safflower oil | 10.2 | 12.6 | 72.1 | 0 | 40.68 |

| Hemp oil | 10 | 15 | 75 | 0 | 12.34 |

| Canola/Rapeseed oil | 5.3 | 64.3 | 24.8 | 0 | 22.21 |

Reactions of fatty acids

Fatty acids exhibit reactions like other carboxylic acids, i.e. they undergo esterification and acid-base reactions.

Acidity

Fatty acids do not show a great variation in their acidities, as indicated by their respective pKa. Nonanoic acid, for example, has a pKa of 4.96, being only slightly weaker than acetic acid (4.76). As the chain length increases, the solubility of the fatty acids in water decreases very rapidly, so that the longer-chain fatty acids have minimal effect on the pH of an aqueous solution. Even those fatty acids that are insoluble in water will dissolve in warm ethanol, and can be titrated with sodium hydroxide solution using phenolphthalein as an indicator to a pale-pink endpoint. This analysis is used to determine the free fatty acid content of fats; i.e., the proportion of the triglycerides that have been hydrolyzed.

Hydrogenation and hardening

Hydrogenation of unsaturated fatty acids is widely practiced to give saturated fatty acids, which are less prone toward rancidification. Since the saturated fatty acids are higher melting than the unsaturated relatives, the process is called hardening. This technology is used to convert vegetable oils into margarine. During partial hydrogenation, unsaturated fatty acids can be isomerized from cis to trans configuration.[17]

More forcing hydrogenation, i.e. using higher pressures of H2 and higher temperatures, converts fatty acids into fatty alcohols. Fatty alcohols are, however, more easily produced from fatty acid esters.

In the Varrentrapp reaction certain unsaturated fatty acids are cleaved in molten alkali, a reaction at one time of relevance to structure elucidation.

Auto-oxidation and rancidity

Unsaturated fatty acids undergo a chemical change known as auto-oxidation. The process requires oxygen (air) and is accelerated by the presence of trace metals. Vegetable oils resist this process because they contain antioxidants, such as tocopherol. Fats and oils often are treated with chelating agents such as citric acid to remove the metal catalysts.

Ozonolysis

Unsaturated fatty acids are susceptible to degradation by ozone. This reaction is practiced in the production of azelaic acid ((CH2)7(CO2H)2) from oleic acid.[17]

Analysis

In chemical analysis, fatty acids are separated by gas chromatography of methyl esters; additionally, a separation of unsaturated isomers is possible by argentation thin-layer chromatography.[18]

Circulation

Digestion and intake

Short- and medium-chain fatty acids are absorbed directly into the blood via intestine capillaries and travel through the portal vein just as other absorbed nutrients do. However, long-chain fatty acids are not directly released into the intestinal capillaries. Instead they are absorbed into the fatty walls of the intestine villi and reassembled again into triglycerides. The triglycerides are coated with cholesterol and protein (protein coat) into a compound called a chylomicron.

From within the cell, the chylomicron is released into a lymphatic capillary called a lacteal, which merges into larger lymphatic vessels. It is transported via the lymphatic system and the thoracic duct up to a location near the heart (where the arteries and veins are larger). The thoracic duct empties the chylomicrons into the bloodstream via the left subclavian vein. At this point the chylomicrons can transport the triglycerides to tissues where they are stored or metabolized for energy.

Metabolism

Fatty acids (provided either by ingestion or by drawing on triglycerides stored in fatty tissues) are distributed to cells to serve as a fuel for muscular contraction and general metabolism. They are broken down to CO2 and water by the intra-cellular mitochondria, releasing large amounts of energy, captured in the form of ATP through beta oxidation and the citric acid cycle.

Distribution

Blood fatty acids are in different forms in different stages in the blood circulation. They are taken in through the intestine in chylomicrons, but also exist in very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) and low density lipoproteins (LDL) after processing in the liver. In addition, when released from adipocytes, fatty acids exist in the blood as free fatty acids.

It is proposed that the blend of fatty acids exuded by mammalian skin, together with lactic acid and pyruvic acid, is distinctive and enables animals with a keen sense of smell to differentiate individuals.[19]

See also

- Fatty acid synthase

- Fatty acid synthesis

- Fatty aldehyde

- List of saturated fatty acids

- List of unsaturated fatty acids

- List of carboxylic acids

- Vegetable oil

References

- ^ IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology (2nd ed.). International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 1997. ISBN 0-521-51150-X. Retrieved 2007-10-31.

- ^ Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism (2012-10-17). "Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism - Abstract of article: Heptanoate as a neural fuel: energetic and neurotransmitter precursors in normal and glucose transporter I-deficient (G1D) brain". Nature.com. Retrieved 2014-03-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cifuentes, Alejandro (ed.). "Microbial Metabolites in the Human Gut". Foodomics: Advanced Mass Spectrometry in Modern Food Science and Nutrition. John Wiley & Sons, 2013. ISBN 9781118169452.

- ^ Roth, Karl S (2013-12-19) Medium-Chain Acyl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. Medscape

- ^ Beermann, C.; Jelinek, J.; Reinecker, T.; Hauenschild, A.; Boehm, G.; Klör, H. -U. (2003). "Short term effects of dietary medium-chain fatty acids and n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on the fat metabolism of healthy volunteers". Lipids in Health and Disease. 2: 10. doi:10.1186/1476-511X-2-10.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Bolsover, Stephen R.; et al. (15 February 2004). Cell Biology: A Short Course. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 42–. ISBN 978-0-471-46159-3.

- ^ a b c Rigaudy, J.; Klesney, S.P. (1979). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry. Pergamon. ISBN 0-08-022369-9. OCLC 5008199.

- ^ "The Nomenclature of Lipids. Recommendations, 1976". European Journal of Biochemistry. 79 (1): 11–21. 1977. doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1977.tb11778.x.

- ^ Elsevier, Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary, Elsevier.

- ^ a b c d e f Stryer, Lubert (1995). "Fatty acid metabolism.". In: Biochemistry (Fourth ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman and Company. pp. 603–628. ISBN 0 7167 2009 4.

- ^ a b Ferre, P.; F. Foufelle (2007). "SREBP-1c Transcription Factor and Lipid Homeostasis: Clinical Perspective". Hormone Research. 68 (2): 72–82. doi:10.1159/000100426. PMID 17344645. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

this process is outlined graphically in page 73

- ^ Voet, Donald; Judith G. Voet; Charlotte W. Pratt (2006). Fundamentals of Biochemistry, 2nd Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. pp. 547, 556. ISBN 0-471-21495-7.

- ^ Zechner R., Strauss J.G., Haemmerle G., Lass A., Zimmermann R. (2005) Lipolysis: pathway under construction. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 16, 333-340.

- ^ Food Standards Agency (1991). "Fats and Oils". McCance & Widdowson's the Composition of Foods. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- ^ Altar, Ted. "More Than You Wanted To Know About Fats/Oils". Sundance Natural Foods. Retrieved 2006-08-31.

- ^ a b "USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference". U. S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ^ a b Anneken, David J. et al. (2006) "Fatty Acids" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_245.pub2

- ^ Breuer, B.; Stuhlfauth, T.; Fock, H. P. (1987). "Separation of Fatty Acids or Methyl Esters Including Positional and Geometric Isomers by Alumina Argentation Thin-Layer Chromatography". Journal of Chromatographic Science. 25 (7): 302–6. doi:10.1093/chromsci/25.7.302. PMID 3611285.

- ^ "Electronic Nose Created To Detect Skin Vapors". Science Daily. July 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-18.