Garden city movement

The garden city movement is a method of urban planning that was initiated in 1898 by Sir Ebenezer Howard in the United Kingdom. Garden cities were intended to be planned, self-contained communities surrounded by "greenbelts", containing proportionate areas of residences, industry, and agriculture.

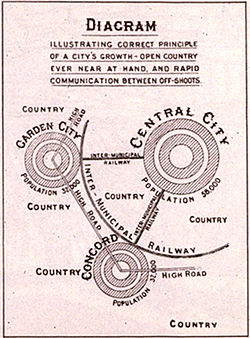

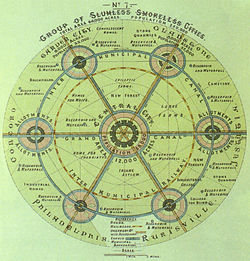

Inspired by the utopian novel Looking Backward and Henry George's work Progress and Poverty, Howard published his book To-morrow: a Peaceful Path to Real Reform in 1898 (which was reissued in 1902 as Garden Cities of To-morrow). His idealised garden city would house 32,000 people on a site of 6,000 acres (2,400 ha), planned on a concentric pattern with open spaces, public parks and six radial boulevards, 120 ft (37 m) wide, extending from the centre. The garden city would be self-sufficient and when it reached full population, another garden city would be developed nearby. Howard envisaged a cluster of several garden cities as satellites of a central city of 250,000 people, linked by road and rail.[1]

Early development

Howard’s To-morrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform sold enough copies to result in a second edition, Garden Cities of To-morrow. This success provided him the support necessary to pursue the chance to bring his vision into reality. Howard believed that all people agreed the overcrowding and deterioration of cities was one of the troubling issues of their time. He quotes a number of respected thinkers and their disdain of cities. Howard’s garden city concept combined the town and country in order to provide the working class an alternative to working on farms or ‘crowded, unhealthy cities’.[2]

To build a garden city, Howard needed money to buy land. He decided to get funding from "gentlemen of responsible position and undoubted probity and honour".[3] He founded the Garden City Association (later known as the Town and Country Planning Association or TCPA), which created First Garden City, Ltd. in 1899 to create the garden city of Letchworth.[4] However, these donors would collect interest on their investment if the garden city generated profits through rents or, as Fishman calls the process, ‘philanthropic land speculation’.[5] Howard tried to include working class cooperative organisations, which included over two million members, but could not win their financial support.[6] Because he had to rely only on the wealthy investors of First Garden City, Howard had to make concessions to his plan, such as eliminating the cooperative ownership scheme with no landlords, short-term rent increases, and hiring architects who did not agree with his rigid design plans.[7]

In 1904, Raymond Unwin, a noted architect and town planner, along with his partner Barry Parker, won the competition run by First Garden City Ltd. to plan Letchworth, an area 34 miles outside London.[8] Unwin and Parker planned the town in the centre of the Letchworth estate with Howard’s large agricultural greenbelt surrounding the town, and they shared Howard’s notion that the working class deserved better and more affordable housing. However, the architects ignored Howard’s symmetric design, instead replacing it with a more ‘organic’ design.[9]

Letchworth slowly attracted more residents because it was able to attract manufacturers through low taxes, low rents and more space.[10] Despite Howard’s best efforts, the home prices in this garden city could not remain affordable for blue-collar workers to live in. The populations comprised mostly skilled middle class workers. After a decade, the First Garden City became profitable and started paying dividends to its investors.[11] Although many viewed Letchworth as a success, it did not immediately inspire government investment into the next line of garden cities.

In reference to the lack of government support for garden cities, Frederic James Osborn, a colleague of Howard and his eventual successor at the Garden City Association, recalled him saying, "The only way to get anything done is to do it yourself."[12] Likely in frustration, Howard bought land at Welwyn to house the second garden city in 1919.[13] The purchase was at auction, with money Howard desperately and successfully borrowed from friends. The Welwyn Garden City Corporation was formed to oversee the construction. But Welwyn did not become self-sustaining because it was only 20 miles from London.[14]

Even until the end of the 1930s, Letchworth and Welwyn remained as the only existing garden cities. However, the movement did succeed in emphasizing the need for urban planning policies that eventually led to the New Town movement.[15]

Garden cities

Howard organised the Garden City Association in 1899. Two garden cities were built using Howard's ideas: Letchworth Garden City and Welwyn Garden City, both in the County of Hertfordshire, England, United Kingdom. Howard's successor as chairman of the Garden City Association was Sir Frederic Osborn, who extended the movement to regional planning.[16]

The concept was adopted again in England after World War II, when the New Towns Act caused the development of many new communities based on Howard's egalitarian ideas.

The idea of the garden city was influential in the United States. Examples are: Residence Park in New Rochelle, New York; Woodbourne in Boston; Newport News, Virginia's Hilton Village; Pittsburgh's Chatham Village; Garden City, New York; Sunnyside, Queens; Jackson Heights, Queens; Forest Hills Gardens, also in the borough of Queens, New York; Radburn, New Jersey; Greenbelt, Maryland; Buckingham in Arlington County, Virginia; the Lake Vista neighborhood in New Orleans; Norris, Tennessee; Baldwin Hills Village in Los Angeles; and the Cleveland suburbs of Parma[17] and Shaker Heights.

Greendale, Wisconsin is one of three "greenbelt" towns planned beginning in 1935 under the direction of Rexford Guy Tugwell, head of the United States Resettlement Administration, under authority of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act. The two other greenbelt towns are Greenbelt, Maryland (near Washington, D.C.) and Greenhills, Ohio (near Cincinnati). The greenbelt towns not only provided work and affordable housing, but also served as a laboratory for experiments in innovative urban planning. Greendale's plan was designed between 1936 and 1937 by a staff headed by Joseph Crane, Elbert Peets, Harry Bentley, and Walter C. Thomas for a site that had formerly consisted of 3,400 acres (14 km2) of farmland.

In Canada, the Ontario towns of Don Mills (now incorporated into the City of Toronto) and Walkerville are, in part, garden cities, as well as the Montreal suburb of Mount Royal. The historic Townsite of Powell River, British Columbia[18] and the Hydrostone district of Halifax, Nova Scotia are recognized as National Historic Sites of Canada[19] built upon the Garden City Movement. In Montreal, La Cité-jardin du Tricentenaire is a classic form of Garden City located near the Olympic Stadium. All streets are cul-de-sacs and are linked via pedestrian paths to the community park.

In Peru, there is a long tradition in urban design[20] that has been reintroduced in its architecture more recently. In 1966, the 'Residencial San Felipe' in the district of Jesus Maria (Lima) was built using the Garden City concept.[21]

In São Paulo, Brazil, several neighbourhoods were planned as Garden Cities, such as Jardim América, Jardim Europa, Alto da Lapa, Alto de Pinheiros, Jardim da Saúde and Cidade Jardim (Garden City in Portuguese). Goiânia, capital of Goiás state, and Maringá are examples of Garden City.

In Argentina, an example is Ciudad Jardín Lomas del Palomar, declared by the influential Argentinian professor of engineering, Carlos María della Paolera, founder of "Día Mundial del Urbanismo" (World Urbanism Day), as the first Garden City in South America.

In Australia, the suburb of Colonel Light Gardens in Adelaide, South Australia, was designed according to garden city principles.[22] So too the town of Sunshine which is now a suburb of Melbourne in Victoria and the suburb of Lalor also in Melbourne Victoria Australia. The Peter Lalor Estate in Lalor takes its name from a leader of the Eureka Stockade and remains today in its original form. However it is under threat from developers and Whittlesea Council.[23][24] Lalor:Peter Lalor Home Building Cooperative 1946-2012 Scollay, Moira. Pre-dating these was the garden suburb of Haberfield in 1901 by Richard Stanton, organised on a vertical integrated model from land subdivision, mortgage financing, house and interior designs and site landscaping.[25]

Garden city ideals were employed in the original town planning of Christchurch, New Zealand. Prior to the earthquakes of 2010 and 2011, the city infrastructure and homes were well integrated into green spaces. The rebuild blueprint rethought the garden city concept and how it would best suit the city. Greenbelts and urban greenspaces have been redesigned to incorporate more living spaces.

Garden city principles greatly influenced the design of colonial and post-colonial capitals during the early part of the 20th century. This is the case for New Delhi (designed as the new capital of British India after World War I), of Canberra (capital of Australia established in 1913) and of Quezon City (established in 1939, capital of the Philippines from 1948–76). The garden city model was also applied to many colonial hill stations, such as Da Lat in Vietnam (est. 1907) and Ifrane in Morocco (est. 1929).

In Bhutan's capital city Thimphu the new plan, following the Principles of Intelligent Urbanism, is an organic response to the fragile ecology. Using sustainable concepts, it is a contemporary response to the garden city concept.

The Garden City movement also influenced the Scottish urbanist Sir Patrick Geddes in the planning of Tel Aviv, Israel, in the 1920s, during the British Mandate for Palestine. Geddes started his Tel Aviv plan in 1925 and submitted the final version in 1927, so all growth of this garden city during the 1930s was merely "based" on the Geddes Plan. Changes were inevitable.[26]

The Garden City movement was even able to take root in South Africa, with the development of the suburb of Pinelands in Cape Town.

In Italy, the INA-Casa plan - a national public housing plan from the 1950s and '60s - designed several suburbs according to Garden City principles: examples are found in many cities and towns of the country, such as the Isolotto suburb in Florence, Falchera in Turin, Harar in Milan, Cesate Villaggio in Cesate (part of the Metropolitan City of Milan), etc.

In the former Czechoslovakia, all industrial cities founded or reconstructed by the Bata Shoes company (Zlín, Svit, Partizánske) were at least influenced by the conception of the Garden city.

The Epcot Center in Bay Lake, Florida took some influence from Howard's Garden City concept while the park was still under construction.[27]

Garden suburbs

It has been suggested that this section be split out into another article titled Garden suburb. (Discuss) (December 2014) |

The concept of garden cities is to produce relatively economically independent cities with short commute times and the preservation of the countryside. Garden suburbs arguably do the opposite. Garden suburbs are built on the outskirts of large cities with no sections of industry. They are therefore dependent on reliable transport allowing workers to commute into the city.[28] Lewis Mumford, one of Howard's disciples explained the difference as "The Garden City, as Howard defined it, is not a suburb but the antithesis of a suburb: not a rural retreat, but a more integrated foundation for an effective urban life."[29]

The planned garden suburb emerged in the late 18th century as a by-product of new types of transportation were embraced by an newly prosperous merchant class. The first garden villages were built by English estate owners, who wanted to relocate or rebuild villages on their lands. It was in these cases that architects first began designing small houses. Early examples include Harewood and Milton Abbas. Major innovations that defined early garden suburbs and subsequent suburban town planning include linking villa-like homes with landscaped public spaces and roads.[30]

Despite the emergence of the garden suburb in England, the typology flowered in the second half of the 19th century in United States. There were generally two garden suburb typologies, the garden village and the garden enclave. The garden villages are spatially independent of the city but remain connected to the city by railroads, streetcars, and later automobiles. The villages often included shops and civic buildings. In contrast, garden enclaves are typically strictly residential and emphasize natural and private space, instead of public and community space. The urban form of the enclaves were often coordinated through the use of early land use controls typical of modern zoning including controlled setbacks, landscaping, materials.[31]

Garden suburbs were not part of Howard's plan[32] and were actually a hindrance to garden city planning—they were in fact almost the antithesis of Howard's plan, what he tried to prevent. The suburbanisation of London was an increasing problem which Howard attempted to solve with his garden city model, which attempted to end urban sprawl by the sheer inhibition of land speculation due to the land being held in trust, and the inclusion of agricultural areas on the city outskirts.[33]

Raymond Unwin, one of Howard's early collaborators on the Letchworth Garden City project in 1907, became very influential in formalizing the garden city principles in the design of suburbs through his work Town Planning in Practice: An Introduction to the Art of Designing Cities and Suburbs (1909). [34] The book strongly influenced the Housing and Town Planning Act of 1909, which provided municipalities the power to develop urban plans for new suburban communities.[35]

Smaller developments were also inspired by the garden city philosophy and were modified to allow for residential "garden suburbs" without the commercial and industrial components of the garden city.[36] They were built on the outskirts of cities, in rural settings. Some notable examples being, in London, Hampstead Garden Suburb, Pinner's Pinnerwood conversation area and the 'Exhibition Estate' in Gidea Park and, in Liverpool, Wavertree Garden Suburb. The Gidea Park estate in particular was built during two main periods of activity, 1911 and 1934. Both resulted in some good examples of domestic architecture, by such architects as Wells Coates and Berthold Lubetkin. Thanks to such strongly conservative local residents' associations as the Civic Society, both Hampstead and Gidea Park retain much of their original character.

However it is important to note Bournville Village Trust in SW Birmingham UK. This important residential development was associated with the growth of 'Cadbury's Factory in a Garden'. Here Garden City principles are a fundamental part of the Trust's activity. There are very tight restrictions applying to the properties here, no stonewall cladding, uPVC windows, and so-on.

Howard's influence reached as far as Mexico City, where architect José Luis Cuevas was influenced by the Garden City concept in the design of two of the most iconic inner-city subdivisions, Colonia Hipódromo de la Condesa (1926) and Lomas de Chapultepec (1928-9):[37]

- In 1926, Colonia Hipódromo[38] (a.k.a. Hipódromo de la Condesa), in what is now known as the Condesa area, including its iconic parks Parque México and Parque España

- In 1928-29, Lomas de Chapultepec

The subdivisions were based on the principles of the Garden City as promoted by Ebenezer Howard, including ample parks and other open spaces, park islands in the middle of "grand avenues" such as Avenida Amsterdam in colonia Hipódromo.[37] One unique example of a garden suburb is the Humberstone Garden Suburb in the United Kingdom by the Humberstone Anchor Tenants' Association in Leicestershire and it is the only garden suburb ever to be built by the members of a workers' co-operative; it remains intact to the present.[39] In 1887 the workers of the Anchor Shoe Company in Humberstone formed a workers' cooperative and built 97 houses.

American architects and partners, Walter Burley Griffin and Marion Mahony Griffin[40] were proponents of the movement and after their arrival in Australia to design the national capital Canberra, they produced a number of Garden Suburb estates, most notably at Eaglemont with the Glenard and Mount Eagle Estates and the Ranelagh and Milleara Estates in Victoria.

Criticisms of the movement

While garden cities were praised for being an alternative to overcrowded and industrial cities, along with greater sustainability, Garden cities were often criticized for damaging the economy, being destructive of the beauty of nature, and being inconvenient. According to A. Trystan Edwards, Garden cities lead to desecration of the country side by trying to recreate country side houses that could spread themselves, however, this wasn't a possible feat due to the limited space they had.[41]

More recently the environmental movement's embrace of urban density has offered an "implicit critique" of the Garden City movement.[42] In this way the critique of the concept resembles critiques of other suburbanization models, though author Stephen Ward has argued that critics often do not adequately distinguish between true garden cities and more mundane dormitory city plans.[42]

It is often referred to as an urban design experiment which is typified by failure due to the laneways used as common entries and exits to the houses helping ghettoise communities and encourage crime; it has ultimately lead to efforts to 'de-Radburn' or partially demolish American Radburn designed public housing areas.[43]

When interviewed in 1998, the architect responsible for introducing the design to public housing in New South Wales, Philip Cox, was reported to have admitted with regards to an American Radburn designed estate in the suburb of Villawood, "Everything that could go wrong in a society went wrong," "It became the centre of drugs, it became the centre of violence and, eventually, the police refused to go into it. It was hell."[43]

Legacy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2009) |

Contemporary town-planning charters like New Urbanism and Principles of Intelligent Urbanism originated with this movement. Today there are many garden cities in the world, but most of them have devolved to dormitory suburbs, which completely differ from what Howard aimed to create.

In 2007, the Town and Country Planning Association marked its 108th anniversary by calling for Garden City and Garden Suburb principles to be applied to the present New Towns and Eco-towns in the United Kingdom.[44] The campaign continues in 2013 with the publication in March of that year of "Creating Garden Cities and Suburbs Today - a guide for councils".[45] Also in 2013, Lord Simon Wolfson announced that he would award the Wolfson Economics Prize for the best ideas on how to create a new garden city.

In 2014 The Letchworth Declaration[46] was published which called for a body to accredit future garden cities in the UK. The declaration has a strong focus on the visible (architecture and layout) and the invisible (social, ownership and governance) architecture of a settlement.

The result was the creation of the New Garden Cities Alliance[47] as a community interest company. Its aim is to be complementary to groups like the Town and Country Planning Association and it has adopted TCPA garden city principles as well as those from other groups, including those from Cabannes\Ross booklet 21st Century Garden Cities of To-morrow.[48] The Alliance has support from architects, planners, institutions, developers and community groups including the winners and shortlisted groups from the Wolfson Economics Prize. The group is working to build that accreditation process it is taking inspiration from the fair trade and transition towns movements. It is working with the British Standards Institute (BSi)[49] too and looking closely at who an accreditation process could be used to raise finance similar to the process for green\climate bonds[50] and social impact bonds. It aims to publish an open source set of principles and methods in XML in early 2016.

See also

Developments influenced by the Garden city movement

- Bedford Park, London, United Kingdom

- Bournville Village, Birmingham UK

- Cité-jardin du Tricentenaire (Tricentennial Garden-City)(1940-1947), Montreal, Canada

- Colonel Lights Gardens, Adelaide, Australia

- Covaresa, Valladolid, Spain

- Den-en-chōfu, Ōta, Tokyo, Japan

- Edgemead, Cape Town, South Africa[51]

- Fairview, Camden, New Jersey, United States

- Gardenvale neighbourhood, Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue, Quebec, Canada (ca. 1918)

- Gartenstadt, Mannheim, Germany

- Giszowiec, Katowice, Poland

- Glenrothes, Scotland, United Kingdom

- Hellerau, Dresden, Germany

- Konstancin-Jeziorna, Poland

- Kowloon Tong, New Kowloon, Hong Kong

- Marino, Dublin, Ireland

- Mežaparks, Riga, Latvia

- Milton Keynes, England, United Kingdom

- Moor Pool, Birmingham, United Kingdom

- Peter Lalor Housing Estate, Lalor, Victoria, Australia

- Pinelands, Cape Town, South Africa

- Podkowa Leśna, Poland

- Reston, Virginia, United States

- Sha Tin, New Territories, Hong Kong

- Sunnyside Gardens Historic District, Queens, New York, United States

- St Helier, London, United Kingdom

- Svit, Slovakia

- Tapiola, Finland

- Telford, United Kingdom

- Ullevål Hageby, Norway

- Town of Mount-Royal, Montreal, Canada

- The Garden Village, Kingston upon Hull, United Kingdom

- Village Homes, Davis, California, United States

- Wekerle-telep, Budapest, Hungary

- Zlín, Czech Republic

- Epcot, Bay Lake, Florida

- Forest Hills, Boston

- Wyvernwood Garden Apartments Los Angeles, California

Related urban design concepts

- Transition Towns

- European Urban Renaissance

- New Pedestrianism

- Transit Oriented Development

- Urban forest

- Principles of Intelligent Urbanism

- Subsistence Homesteads Division

- Soviet urban planning ideologies of the 1920s

References

- ^ Goodall, B (1987), Dictionary of Human Geography, London: Penguin.

- ^ Howard, E (1902), Garden Cities of To-morrow (2nd ed.), London: S. Sonnenschein & Co, pp. 2–7.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 42.

- ^ Hardy 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 43.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 46.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 47.

- ^ Hall 2002, p. 68.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Fainstein & Campbell 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Hall 2002, p. 100.

- ^ Hall & Ward 1998, pp. 45–7.

- ^ Hardy 1999, p. 8.

- ^ Hall & Ward 1998, p. 46.

- ^ Hall & Ward 1998, pp. 52–3.

- ^ History 1899–1999 (PDF), TCPA.

- ^ Horley, Robert (1998). The Best Kept Secrets of Parma, "The Garden City". Robert Horley. ISBN 0-9661721-0-8.

- ^ http://powellrivertownsite.com

- ^ http://www.historicplaces.ca/en/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=10728&pid=0

- ^ examples being the ancient city of Chan Chan (20 km², 850 AD) in Trujillo, north of Lima, and the Inca's 12th-century city of Machu Picchu. Peru's modern capital, Lima, was designed in 1535 by Spanish Conquistadors to replace its ancient past as a religious sanctuary with 37 pyramids.

- ^ 37676518 (photogram), Panoramio.

- ^ City of Mitcham - History Pages

- ^ "HV McKay memorial gardens", Victorian Heritage Database, Vic, AU: The Government.

- ^ "2000 Study Site N 068—Albion—HO Selwyn Park", Post-contact Cultural Heritage Study (PDF), Vic, AU: Brimbank City Council.

- ^ Sue Jackson-Stepowski (2008). "Haberfield". Retrieved 2016-04-26.

- ^ Webberley, Helen (2008), Town-planning in a Brand New City, Brisbane: AAANZ Conference.

- ^ http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/2346/

- ^ Hall & Ward 1998, p. 41.

- ^ Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 1580933262.

- ^ Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. ISBN 1580933262.

- ^ Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. p. 48. ISBN 1580933262.

- ^ Hall, Peter (1996), "4", Cities of Tomorrow, Oxford: BlackWell.

- ^ Design on the Land.

- ^ Hall 2002, pp. 110–12.

- ^ Stern, Robert A.M.; Fishman, David; Tilove, Jacob (2013). Paradise Planned: The Garden Suburb and the Modern City. The Monacelli Press. p. 214. ISBN 1580933262.

- ^ Hollow, Matthew (2011). "Suburban Ideals on England's Interwar Council Estates". Retrieved 2012-12-29.

- ^ a b Manuel Sánchez de Carmona; et al., El trazo de Las Lomas y de la Hipódromo Condesa (PDF) (in Spanish)

- ^ "Histoira de la Arquitectura Mexicana", Gabriela Piña Olivares, Autonomous University of Hidalgo

- ^ "Humberstone Garden Suburb". UK: Utopia Britannica. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Goad, Philip (2012). The Encyclopedia of Australian Architecture. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ A. Trystan Edwards (January 1914). "A Further Criticism of the Garden City Movement". The Town Planning Review. 4 (4): 312–318. JSTOR 40100071.

- ^ a b Stephen Ward (18 October 2005). The Garden City: Past, present and future. Routledge. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-1-135-82895-0.

- ^ a b Dylan Welch (2009-01-08). "Demolition ordered for Rosemeadow estate". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Garden Cities at Town and Country Planning Association

- ^ "Creating Garden Cities and Suburbs Today - a guide for councils"

- ^ Letchworth Declaration

- ^ [1] New Garden Cities Alliance

- ^ [2] 21st Century Garden Cities of To-morrow. A manifesto. Cabannes\Ross (2015) ISBN 1291478272)

- ^ BSi

- ^ [3] Climate Bonds

- ^ "Over 90 years of community building". http://www.gardencities.co.za/.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website=

Bibliography

- Fainstein, S; Campbell, S (2003), Readings in planning theory, Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

- Hall, P (2002), Cities of Tomorrow (3rd ed.), Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell.

- ———; Ward, C (1998), Sociable Cities: the Legacy of Ebenezer Howard, Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hardy, D (1999), 1899–1999, London: Town and Country Planning Association.

- Ross, P; Cabannes, Y (2012), 21st Century Garden Cities of To-morrow - How to become a Garden City, Letchworth Garden City: New Garden City Movement.

External links

- Sir Ebenezer Howard and the Garden City Movement Norman Lucey 1973

- Patrick Barkham Britain’s housing crisis: are garden cities the answer? 2 October 2014

- L. Bigon and Y. Katz (eds 2014), Garden Cities and Colonial Planning: Transnationality and Urban Ideas in Africa and Palestine Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press.