Giuseppe Garibaldi

Giuseppe Garibaldi | |

|---|---|

Garibaldi in 1866 | |

| Dictator of Sicily | |

| In office 17 May 1860 – 4 November 1860 | |

| |

| In office 18 February 1861 – 2 June 1882 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Giuseppe Maria Garibaldi 4 July 1807 Nice, First French Empire |

| Died | 2 June 1882 (aged 74) Caprera, Kingdom of Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Political party |

|

| Spouses | |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | List of allegiances: |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1835–1871 |

| Rank | General |

| Commands | |

| Battles/wars | List of wars:

|

Giuseppe Garibaldi (Italian: [dʒuˈzɛppe ɡariˈbaldi]); 4 July 1807 – 2 June 1882) was an Italian general and nationalist. A republican, he contributed to the Italian unification and the creation of the Kingdom of Italy. He is considered one of the greatest generals of modern times[1] and one of Italy's "fathers of the fatherland" along with Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy and Giuseppe Mazzini.

Garibaldi is also known as the "Hero of the Two Worlds" because of his military enterprises in Brazil, Uruguay and Europe.[2] He commanded and fought in many military campaigns that led eventually to the Italian unification. In 1848, the provisional government of Milan made Garibaldi a general, and in 1849, the Minister of War promoted him to General of the Roman Republic to lead the Expedition of the Thousand on behalf and with the consent of Victor Emmanuel II. His last military campaign took place during the Franco-Prussian War, as commander of the Army of the Vosges.

Garibaldi was very popular in Italy and abroad, aided by exceptional international media coverage at the time. Many great intellectuals of the time, such as Victor Hugo, Alexandre Dumas, and George Sand, showered him with admiration. The United Kingdom and the United States helped him a great deal, offering him financial and military support in difficult circumstances. In the popular telling of his story, he is associated with the red shirts that his volunteers, the Garibaldini, wore in lieu of a uniform.

Early life

Garibaldi was born and christened Joseph-Marie Garibaldi[3] on 4 July 1807 in Nice, which had been directly annexed by the First French Empire in 1805, to the Ligurian family of Giovanni Domenico Garibaldi from Chiavari[4] and Maria Rosa Nicoletta Raimondo from Loano.[5] In 1814, the Congress of Vienna returned Nice to Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia; nevertheless, France re-annexed it in 1860 by the Treaty of Turin, which was ardently opposed by Garibaldi.

Garibaldi's family's involvement in coastal trade drew him to a life at sea. He participated actively in the Nizzardo Italians community and was certified in 1832 as a merchant navy captain.

In April 1833 he travelled to Taganrog, Russia, in the schooner Clorinda with a shipment of oranges. During ten days in port he met Giovanni Battista Cuneo from Oneglia, a politically active immigrant and member of the secret Young Italy movement of Giuseppe Mazzini. Mazzini was an impassioned proponent of Italian unification as a liberal republic through political and social reform. Garibaldi joined the society and took an oath dedicating himself to the struggle to liberate and unify his homeland free from Austrian dominance.

In Geneva during November 1833, Garibaldi met Mazzini, starting a long relationship that later became troublesome. He joined the Carbonari revolutionary association, and in February 1834 participated in a failed Mazzinian insurrection in Piedmont. A Genoese court sentenced Garibaldi to death in absentia, and he fled across the border to Marseille.

South American period

Garibaldi first sailed to Tunisia before eventually finding his way to the Empire of Brazil. Once there, he took up the cause of Republic of Rio Grande do Sul in its attempt to separate from Brazil, joining the rebels known as the Ragamuffins in the Ragamuffin War.

During this war he met Ana Ribeiro da Silva, commonly known as Anita. When the Ragamuffins tried to proclaim another republic in the Brazilian province of Santa Catarina in October 1839, she joined him aboard his ship, Rio Pardo, and fought alongside him at the battles of Imbituba and Laguna.

In 1841, Garibaldi and Anita moved to Montevideo, Uruguay, where Garibaldi worked as a trader and schoolmaster. The couple married in Montevideo the following year. They had four children[6] – Menotti (born 1840), Rosita (born 1843), Teresita (born 1845), and Ricciotti (born 1847). A skilled horsewoman, Anita is said to have taught Giuseppe about the gaucho culture of southern Brazil and Uruguay. Around this time, he adopted his trademark clothing—the red shirt, poncho, and sombrero commonly worn by gauchos.

In 1842, Garibaldi took command of the Uruguayan fleet and raised an "Italian Legion" of soldiers known as Redshirts, who wore red, blouse-type shirts, for the Uruguayan Civil War. He aligned his forces with the Uruguayan Colorados led by Fructuoso Rivera, who were aligned with the Argentine Unitarios. This faction received some support from the French and British Empires in their struggle against the forces of former Uruguayan president Manuel Oribe's Blancos, which was also aligned with Argentine Federales under the rule of Buenos Aires caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas.

The Italian Legion adopted a black flag that represented Italy in mourning, with a volcano at the center that symbolized the dormant power in their homeland. Though contemporary sources don't mention the red shirts, popular history asserts that the legion first wore them in Uruguay, getting them from a factory in Montevideo that had intended to export them to the slaughterhouses of Argentina. These shirts became the symbol of Garibaldi and his followers.

Between 1842 and 1848, Garibaldi defended Montevideo against forces led by Oribe. In 1845 he managed to occupy Colonia del Sacramento and Martín García Island, and led the controversial sack of Gualeguaychú during the Anglo-French blockade of the Río de la Plata. Adopting guerrilla tactics, Garibaldi later achieved two victories during 1846, in the Battle of Cerro and the Battle of San Antonio del Santo.

Induction to Freemasonry

Garibaldi joined Freemasonry during his exile, taking advantage of the asylum the lodges offered to political refugees from European countries governed by despotic regimes. At the age of thirty-seven, during 1844, Garibaldi was initiated in the "L'Asil de la Vertud" Lodge of Montevideo. This was an irregular lodge under a Brazilian Freemasonry not recognized by the main international masonic obediences, such as the United Grand Lodge of England or the Grand Orient de France. While Garibaldi had little use for masonic rituals, he was an active Freemason and regarded Freemasonry as a network that united progressive men as brothers both within nations and as a global community. Garibaldi was eventually elected as the Grand Master of the Grand Orient of Italy.[7][8]

Garibaldi later regularized his position in 1844, joining the lodge "Les Amis de la Patrie" of Montevideo under the Grand Orient of France.

1846 Election of Pope Pius IX

The fate of his homeland, however, continued to concern Garibaldi. The election of Pope Pius IX in 1846 caused a sensation among Italian patriots, both at home and in exile. Pius's initial reforms seemed to identify him as the liberal pope called for by Vincenzo Gioberti, who went on to lead the unification of Italy. When news of these reforms reached Montevideo, Garibaldi wrote to the Pope:

If these hands, used to fighting, would be acceptable to His Holiness, we most thankfully dedicate them to the service of him who deserves so well of the Church and of the fatherland. Joyful indeed shall we and our companions in whose name we speak be, if we may be allowed to shed our blood in defence of Pius IX's work of redemption

— 12 October 1847[9]

Mazzini, from exile, also applauded the early reforms of Pius IX. In 1847, Garibaldi offered the apostolic nuncio at Rio de Janeiro, Bedini, the service of his Italian Legion for the liberation of the peninsula. Then news of an outbreak of revolution in Palermo in January 1848 and revolutionary agitation elsewhere in Italy encouraged Garibaldi to lead around sixty members of his legion home.

Return to Italy

Garibaldi returned to Italy amidst the turmoil of the revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states and offered his services to Charles Albert of Sardinia. The monarch displayed some liberal inclinations, but treated Garibaldi with coolness and distrust. Rebuffed by the Piedmontese, he and his followers crossed into Lombardy where they offered assistance to the provisional government of Milan, which had rebelled against the Austrian occupation. In the course of the following unsuccessful First Italian War of Independence, Garibaldi led his legion to two minor victories at Luino and Morazzone.

After the crushing Piedmontese defeat at Novara (23 March 1849), Garibaldi moved to Rome to support the Republic recently proclaimed in the Papal States, but a French force sent by Louis Napoleon (the future Napoleon III) threatened to topple it. At Mazzini's urging, Garibaldi took command of the defence of Rome. In fighting near Velletri, Achille Cantoni saved his life. After Cantoni's death, during the Battle of Mentana, Garibaldi wrote the novel Cantoni il volontario (Cantoni the Volunteer).

On 30 April 1849 the Republican army, under Garibaldi's command, defeated a numerically far superior French army. Subsequently, French reinforcements arrived, and the siege of Rome began on 1 June. Despite the resistance of the Republican army, the French prevailed on 29 June. On 30 June the Roman Assembly met and debated three options: surrender, continue fighting in the streets, or retreat from Rome to continue resistance from the Apennine mountains. Garibaldi made a speech that favored the third option, ending with: Dovunque saremo, colà sarà Roma.[10] (Wherever we may be, there will be Rome).

The sides negotiated a truce on 1 July, and on 2 July Garibaldi withdrew from Rome with 4,000 troops. The French Army entered Rome on 3 July and reestablished the Holy See's temporal power. Garibaldi and his forces, hunted by Austrian, French, Spanish, and Neapolitan troops, fled to the north, intending to reach Venice, where the Venetians were still resisting the Austrian siege. After an epic march, Garibaldi took momentary refuge in San Marino, with only 250 men still following him. Anita, who was carrying their fifth child, died near Comacchio during the retreat.

North America and the Pacific

Garibaldi eventually managed to reach Porto Venere, near La Spezia, but the Piedmontese government forced him to emigrate again.

He went to Tangier, where he stayed with Francesco Carpanetto, a wealthy Italian merchant. Carpanetto suggested that he and some of his associates finance the purchase of a merchant ship, which Garibaldi would command. Garibaldi agreed, feeling that his political goals were, for the moment, unreachable, and he could at least earn his own living.[11]

The ship was to be purchased in the United States, so Garibaldi went to New York, arriving on 30 July 1850. However, the funds for purchasing a ship were lacking. While in New York, he stayed with various Italian friends, including some exiled revolutionaries. He attended the masonic lodges of New York in 1850, where he met several supporters of democratic internationalism, whose minds were open to socialist thought, and to giving Freemasonry a strong anti-papal stance.[8]

The inventor Antonio Meucci employed Garibaldi in his candle factory on Staten Island.[12] (The cottage on Staten Island where he stayed is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places and is preserved as the Garibaldi Memorial.) Garibaldi was not satisfied with this, and in April 1851 he left New York with his friend Carpanetto for Central America, where Carpanetto was establishing business operations. They went first to Nicaragua, and then to other parts of the region. Garibaldi accompanied Carpanetto as a companion, not a business partner, and used the name Giuseppe Pane.[11]

Carponetto went on to Lima, Peru, where a shipload of his goods was due, arriving late in 1851 with Garibaldi. En route, Garibaldi called on Andean revolutionary heroine Manuela Sáenz. At Lima, Garibaldi was generally welcomed. A local Italian merchant, Pietro Denegri, gave him command of his ship Carmen for a trading voyage across the Pacific. Garibaldi took the Carmen to the Chincha Islands for a load of guano. Then on 10 January 1852, he sailed from Peru for Canton, China, arriving in April.[11]

After side trips to Xiamen and Manila, Garibaldi brought the Carmen back to Peru via the Indian Ocean and the South Pacific, passing clear around the south coast of Australia. He visited Three Hummock Island in Bass Strait.[11] Garibaldi then took the Carmen on a second voyage: to the United States via Cape Horn with copper from Chile, and also wool. Garibaldi arrived in Boston, and went on to New York. There he received a hostile letter from Denegri, and resigned his command.[11] Another Italian, Captain Figari, had just come to the U.S. to buy a ship, and hired Garibaldi to take the ship to Europe. Figari and Garibaldi bought the Commonwealth in Baltimore, and Garibaldi left New York for the last time in November 1853.[12] He sailed the Commonwealth to London, and then to Newcastle on the River Tyne for coal.[11]

Tyneside

The Commonwealth arrived on 21 March 1854. Garibaldi, already a popular figure on Tyneside, was welcomed enthusiastically by local working men-though the Newcastle Courant reported that he refused an invitation to dine with dignitaries in the city. He stayed in Huntingdon Place Tynemouth for a few days,[13] and in South Shields on Tyneside for over a month, departing at the end of April 1854. During his stay, he was presented with an inscribed sword, which his grandson Giuseppe Garibaldi II later carried as a volunteer in British service in the Second Boer War.[14] He then sailed to Genoa, where his five years of exile ended on 10 May 1854.[11]

Second Italian War of Independence

Garibaldi returned again to Italy in 1854. Using an inheritance from the death of his brother, he bought half of the Italian island of Caprera (north of Sardinia), devoting himself to agriculture. In 1859, the Second Italian War of Independence (also known as the Austro-Sardinian War) broke out in the midst of internal plots at the Sardinian government. Garibaldi was appointed major general, and formed a volunteer unit named the Hunters of the Alps (Cacciatori delle Alpi). Thenceforth, Garibaldi abandoned Mazzini's republican ideal of the liberation of Italy, assuming that only the Piedmontese monarchy could effectively achieve it. He and his volunteers won victories over the Austrians at Varese, Como, and other places.

Garibaldi was, however, very displeased, as his home city of Nice (Nizza in Italian) had surrendered to the French in return for crucial military assistance. In April 1860, as deputy for Nice in the Piedmontese parliament at Turin, he vehemently attacked Cavour for ceding Nice and the County of Nice (Nizzardo) to Louis Napoleon, Emperor of France. In the following years, Garibaldi (with other passionate Nizzardo Italians) promoted the Italian irredentism of his Nizza, even with riots (in 1872).

Campaign of 1860

On 24 January 1860, Garibaldi married an 18-year-old Lombard woman, Giuseppina Raimondi. Immediately after the wedding ceremony, she informed him that she was pregnant with another man's child and Garibaldi left her the same day.[15]

At the beginning of April 1860, uprisings in Messina and Palermo in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies provided Garibaldi with an opportunity. He gathered about a thousand volunteers – called i Mille (the Thousand), or, as popularly known, the Redshirts – in two ships named Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, and left from Genoa on 5 May in the evening and landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily, on 11 May.

Swelling the ranks of his army with scattered bands of local rebels, Garibaldi led 800 volunteers to victory over an enemy force of 1500 on the hill of Calatafimi on 15 May. He used the counter-intuitive tactic of an uphill bayonet charge. He saw that the hill was terraced, and the terraces would shelter his advancing men. Though small by comparison with the coming clashes at Palermo, Milazzo and Volturno, this battle was decisive in establishing Garibaldi's power in the island. An apocryphal but realistic story had him say to his lieutenant Nino Bixio, Qui si fa l'Italia o si muore, that is, Here we either make Italy, or we die. In reality, the Neapolitan forces were ill guided, and most of its higher officers had been bought out. The next day, he declared himself dictator of Sicily in the name of Victor Emmanuel II of Italy. He advanced to the outskirts of Palermo, the capital of the island, and launched a siege on 27 May. He had the support of many inhabitants, who rose up against the garrison—but before they could take the city, reinforcements arrived and bombarded the city nearly to ruins. At this time, a British admiral intervened and facilitated an armistice, by which the Neapolitan royal troops and warships surrendered the city and departed. Historians Clough et al. argue that Garibaldi’s Thousand were students, independent artisans, and professionals, not peasants. The support given by Sicilian peasants was from patriotism, but from their hatred of exploitative landlords and oppressive Neapolitan officials. Garibaldi himself had no interest in social revolution, and instead sided with the Sicilian landlords against the rioting peasants.[16]

By conquering Palermo, Garibaldi had won a signal victory. He gained worldwide renown and the adulation of Italians. Faith in his prowess was so strong that doubt, confusion, and dismay seized even the Neapolitan court. Six weeks later, he marched against Messina in the east of the island, winning a ferocious and difficult battle at Milazzo. By the end of July, only the citadel resisted.

Having conquered Sicily, he crossed the Strait of Messina and marched north. Garibaldi's progress was met with more celebration than resistance, and on 7 September he entered the capital city of Naples, by train. Despite taking Naples, however, he had not to this point defeated the Neapolitan army. Garibaldi's volunteer army of 24,000 was not able to defeat conclusively the reorganized Neapolitan army (about 25,000 men) on 30 September at the Battle of Volturno. This was the largest battle he ever fought, but its outcome was effectively decided by the arrival of the Piedmontese Army. Following this, Garibaldi's plans to march on to Rome were jeopardized by the Piedmontese, technically his ally but unwilling to risk war with France, whose army protected the Pope. (The Piedmontese themselves had conquered most of the Pope's territories in their march south to meet Garibaldi, but they had deliberately avoided Rome, capital of the Papal state.) Garibaldi chose to hand over all his territorial gains in the south to the Piedmontese and withdrew to Caprera and temporary retirement. Some modern historians consider the handover of his gains to the Piedmontese as a political defeat, but he seemed willing to see Italian unity brought about under the Piedmontese crown. The meeting at Teano between Garibaldi and Victor Emmanuel II is the most important event in modern Italian history, but is so shrouded in controversy that even the exact site where it took place is in doubt.

Aftermath

Garibaldi deeply disliked the Sardinian Prime Minister, Camillo Benso, Count of Cavour. To an extent, he simply mistrusted Cavour's pragmatism and realpolitik, but he also bore a personal grudge for Cavour's trading away his home city of Nice to the French the previous year. On the other hand, he felt attracted toward the Piedmontese monarch, who in his opinion had been chosen by Providence for the liberation of Italy. In his famous meeting with Victor Emmanuel II at Teano on 26 October 1860, Garibaldi greeted him as King of Italy and shook his hand. Garibaldi rode into Naples at the king's side on 7 November, then retired to the rocky island of Caprera, refusing to accept any reward for his services.[citation needed]

At the outbreak of the American Civil War (in 1861), Garibaldi volunteered his services to President Abraham Lincoln. Garibaldi was offered a major general’s commission in the U. S. Army through the letter from Secretary of State William H. Seward to H. S. Sanford, the U. S. Minister at Brussels, July 17, 1861.[17] On September 18, 1861, Sanford sent the following reply to Seward:

- He [Garibaldi] said that the only way in which he could render service, as he ardently desired to do, to the cause of the United States, was as Commander-in-chief of its forces, that he would only go as such, and with the additional contingent power—to be governed by events—of declaring the abolition of slavery; that he would be of little use without the first, and without the second it would appear like a civil war in which the world at large could have little interest or sympathy.[18]

These conditions could not be met. On August 6, 1863, after the Emancipation Proclamation had been issued, Garibaldi wrote to Lincoln, "Posterity will call you the great emancipator, a more enviable title than any crown could be, and greater than any merely mundane treasure".[19]

On 5 October 1861, Garibaldi set up the International Legion bringing together different national divisions of French, Poles, Swiss, German and other nationalities, with a view not just of finishing the liberation of Italy, but also of their homelands. With the motto "Free from the Alps to the Adriatic," the unification movement set its gaze on Rome and Venice. Mazzini was discontented with the perpetuation of monarchial government, and continued to agitate for a republic. Garibaldi, frustrated at inaction by the king, and bristling over perceived snubs, organized a new venture. This time, he intended to take on the Papal States.

Expedition against Rome

Garibaldi himself was intensely anti-Catholic and anti-papal. His efforts to overthrow the pope by military action mobilized anti-Catholic support. For example, there were major anti-Catholic riots in his name across Britain in 1862, with the Irish Catholics fighting in defense of their Church.[20][21] Garibaldi's hostility to the Pope's temporal domain was viewed with great distrust by Catholics around the world, and the French emperor Napoleon III had guaranteed the independence of Rome from Italy by stationing a French garrison in Rome. Victor Emmanuel was wary of the international repercussions of attacking the Papal States, and discouraged his subjects from participating in revolutionary ventures with such intentions. Nonetheless, Garibaldi believed he had the secret support of his government.

In June 1862, he sailed from Genoa to Palermo to gather volunteers for the impending campaign, under the slogan Roma o Morte (Rome or Death). An enthusiastic party quickly joined him, and he turned for Messina, hoping to cross to the mainland there. He arrived with a force of around two thousand, but the garrison proved loyal to the king's instructions and barred his passage. They turned south and set sail from Catania, where Garibaldi declared that he would enter Rome as a victor or perish beneath its walls. He landed at Melito on 14 August, and marched at once into the Calabrian mountains.

Far from supporting this endeavor, the Italian government was quite disapproving. General Enrico Cialdini dispatched a division of the regular army, under Colonel Emilio Pallavicini, against the volunteer bands. On 28 August the two forces met in the rugged Aspromonte. One of the regulars fired a chance shot, and several volleys followed, killing a few of the volunteers. The fighting ended quickly, as Garibaldi forbade his men to return fire on fellow subjects of the Kingdom of Italy. Many of the volunteers were taken prisoner, including Garibaldi, who had been wounded by a shot in the foot. (The episode was the origin of a famous Italian nursery rhyme: Garibaldi fu ferito "Garibaldi was wounded").

A government steamer took him to a prison at Varignano near La Spezia, where he was held in a sort of honorable imprisonment and underwent a tedious and painful operation to heal his wound. His venture had failed, but he was consoled by Europe's sympathy and continued interest. One historian of the American Civil War wrote that the distraction created by Garibaldi's wounding, followed by his unequivocal endorsement of the Union cause, was as important as Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation in preserving British and French neutrality in the American conflict—thus significantly aiding the Northern cause.[22] After he regained his health, the government released Garibaldi and let him return to Caprera.

En route to London in 1864 he stopped briefly in Malta, where many admirers visited him in his hotel.[23] Feeble protests by opponents of his anticlericalism were easily suppressed by the British colonial authorities. In London his presence was received with enthusiasm by the population.[24] He met the British prime minister Viscount Palmerston, as well as revolutionaries then living in exile in the city. At that time, his ambitious international project included the liberation of a range of occupied nations, such as Croatia, Greece, and Hungary. He also visited Bedford and was given a tour of the Britannia Iron Works, where he planted a tree (which was cut down in 1944 due to decay).[25]

Final struggle with Austria, and other adventures

Garibaldi took up arms again in 1866, this time with the full support of the Italian government. The Austro-Prussian War had broken out, and Italy had allied with Prussia against the Austrian Empire in the hope of taking Venetia from Austrian rule (Third Italian War of Independence). Garibaldi gathered again his Hunters of the Alps, now some 40,000 strong, and led them into the Trentino. He defeated the Austrians at Bezzecca (securing the only Italian victory in that war) and made for Trento.

The Italian regular forces were defeated at Lissa on the sea, and made little progress on land after the disaster of Custoza. The sides signed an armistice by which Austria ceded Venetia to Italy, but this result was largely due to Prussia's successes on the northern front. Garibaldi's advance through Trentino was for nought, and he was ordered to stop his advance to Trento. Garibaldi answered with a short telegram from the main square of Bezzecca with the famous motto: Obbedisco! ("I obey!") .

After the war, Garibaldi led a political party that agitated for the capture of Rome, the peninsula's ancient capital. In 1867, he again marched on the city, but the Papal army, supported by a French auxiliary force, proved a match for his badly armed volunteers. He was shot in the leg in the Battle of Mentana, and had to withdraw from the Papal territory. The Italian government again imprisoned him for some time, after which he returned to Caprera.

In the same year, Garibaldi sought international support for altogether eliminating the papacy. At an 1867 congress in Geneva he proposed: "The papacy, being the most harmful of all secret societies, ought to be abolished."[26]

When the Franco-Prussian War broke out in July 1870, Italian public opinion heavily favored the Prussians, and many Italians attempted to sign up as volunteers at the Prussian embassy in Florence. After the French garrison was recalled from Rome, the Italian Army captured the Papal States without Garibaldi's assistance. Following the wartime collapse of the Second French Empire at the Battle of Sedan, Garibaldi, undaunted by the recent hostility shown to him by the men of Napoleon III, switched his support to the newly declared French Third Republic. On 7 September 1870, within three days of the revolution of 4 September in Paris, he wrote to the Movimento of Genoa, "Yesterday I said to you: war to the death to Bonaparte. Today I say to you: rescue the French Republic by every means."[27] Subsequently, Garibaldi went to France and assumed command of the Army of the Vosges, an army of volunteers.

Death

Despite being elected again to the Italian parliament, Garibaldi spent much of his late years in Caprera.[6] He however supported an ambitious project of land reclamation in the marshy areas of southern Lazio. In 1879 he founded the League of Democracy, which advocated universal suffrage, abolition of ecclesiastical property, emancipation of women, and maintenance of a standing army. Ill and confined to bed by arthritis, he made trips to Calabria and Sicily. In 1880, he married Francesca Armosino, with whom he previously had three children.

On his deathbed, Garibaldi asked for his bed to be moved to where he could gaze at the emerald and sapphire sea. On his death on 2 June 1882 at the age of almost 75, his wishes for a simple funeral and cremation were not respected. He was buried in his farm on the island of Caprera alongside his last wife and some of his children.[28]

In 2012, Garibaldi's descendants announced that, with permission from authorities, they would have Garibaldi's remains exhumed to confirm through DNA analysis that the remains in the tomb are indeed Garibaldi's. Some anticipated that there would be a debate about whether to preserve the remains or to grant his final wish for a simple cremation.[29] In 2013, personnel changes at the Ministry of Culture sidelined the exhumation plans. The new authorities were "less than enthusiastic" about the plan.[30]

Writings

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2008) |

Garibaldi wrote at least two novels, characterized by an anti-clerical tone:

- Clelia or Il governo dei preti (1867) english translation, t. 1 english translation, t. 2

- Cantoni il volontario (1870)

- I Mille (1873)

He also wrote non-fiction:

- Autobiography[31] (v. 1 1807–1849)

- Memoirs,[32] co-authored by Alexandre Dumas

- A translation of his memoirs is The life of Garibaldi written by himself (New York: Barnes, 1859)

Legacy

Garibaldi's popularity, skill at rousing the common people, and his military exploits are all credited with making the unification of Italy possible. He also served as a global exemplar of mid-19th century revolutionary nationalism and liberalism—but after the liberation of southern Italy from the Neapolitan monarchy, Garibaldi chose to sacrifice his liberal republican principles for the sake of unification.

Garibaldi subscribed to the anti-clericalism common among Latin liberals, and did much to circumscribe the temporal power of the Papacy. His personal religious convictions are unclear to historians—in 1882 he wrote "Man created God, not God created Man," yet in his autobiography he is quoted as saying, "I am a Christian, and I speak to Christians – I am a true Christian, and I speak to true Christians. I love and venerate the religion of Christ, because Christ came into the world to deliver humanity from slavery," and, "You have the duty to educate the people—educate the people—educate them to be Christians—educate them to be Italians ... Viva Italia! Viva Christianity!"[33] The Protestant minister Alessandro Gavazzi was his army chaplain.

Giuseppe Garibaldi died at Caprera in 1882, where he was interred. Five ships of the Italian Navy have been named after him, including a World War II cruiser and the former flagship, the aircraft carrier Giuseppe Garibaldi. Statues of his likeness, as well as the handshake of Teano, stand in many Italian squares, and in other countries around the world. On the top of the Janiculum hill in Rome, there is a statue of Garibaldi on horse-back. His face was originally turned in the direction of the Vatican (an allusion[citation needed] to his ambition to conquer the Papal States), but after the Lateran Treaty in 1929 the orientation of the statue was changed at the Vatican's request.[citation needed] A bust of Giuseppe Garibaldi is prominently placed outside the entrance to the old Supreme Court Chamber in the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, DC, a gift from members of the Italian Society of Washington. Many theatres in Sicily take their name from him and are named Garibaldi Theatre.

Garibaldi was a popular hero in Britain. In a book review in The New Yorker (9 and 16 July 2007) of a Garibaldi biography, Tim Parks cites the English historian, A. J. P. Taylor, as saying, "Garibaldi is the only wholly admirable figure in modern history."[34] The reputation stems from a monumental trilogy (1907–11), by G. M. Trevelyan. According to David Cannadine:

It depicted Garibaldi as a Carlylean hero—poet, patriot, and man of action—whose inspired leadership created the Italian nation. For Trevelyan, Garibaldi was the champion of freedom, progress, and tolerance, who vanquished the despotism, reaction, and obscurantism of the Austrian empire and the Neapolitan monarchy. The books were also notable for their vivid evocation of landscape (Trevelyan had himself followed the course of Garibaldi's marches), for their innovative use of documentary and oral sources, and for their spirited accounts of battles and military campaigns.[35]

In 1865, English football team Nottingham Forest chose their home colours from the uniform worn by Garibaldi and his men in 1865.[36] A school in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire was also named after him.[37] The Garibaldi biscuit was named after him, as was a style of beard. The Giuseppe Garibaldi Trophy has been awarded annually since 2007 within the Six Nations rugby union framework to the victor of the match between France and Italy, in the memory of Garibaldi.[citation needed]

Garibaldi, along with Giuseppe Mazzini and other Europeans, supported the creation of a European federation. Many Europeans expected that the 1871 unification of Germany would make Germany a European and world leader that would champion humanitarian policies. This idea is apparent in the following letter Giuseppe Garibaldi sent to Karl Blind on 10 April 1865:

The progress of humanity seems to have come to a halt, and you with your superior intelligence will know why. The reason is that the world lacks a nation which possesses true leadership. Such leadership, of course, is required not to dominate other peoples, but to lead them along the path of duty, to lead them toward the brotherhood of nations where all the barriers erected by egoism will be destroyed. We need the kind of leadership which, in the true tradition of medieval chivalry, would devote itself to redressing wrongs, supporting the weak, sacrificing momentary gains and material advantage for the much finer and more satisfying achievement of relieving the suffering of our fellow men. We need a nation courageous enough to give us a lead in this direction. It would rally to its cause all those who are suffering wrong or who aspire to a better life, and all those who are now enduring foreign oppression. This role of world leadership, left vacant as things are today, might well be occupied by the German nation. You Germans, with your grave and philosophic character, might well be the ones who could win the confidence of others and guarantee the future stability of the international community. Let us hope, then, that you can use your energy to overcome your moth-eaten thirty tyrants of the various German states. Let us hope that in the center of Europe you can then make a unified nation out of your fifty millions. All the rest of us would eagerly and joyfully follow you.[38]

On 18 February 1960, the American television series Dick Powell's Zane Grey Theatre aired the episode "Guns for Garibaldi" to commemorate the centennial of the unification of Italy. This was the only such program to emphasize the role of Italians in pre-Civil War America. The episode is set in Indian Creek, a western gold mining town. Giulio Mandati, played by Fernando Lamas, takes over his brother's gold claim. People in Indian Creek wanted to use the gold to finance a dam, but Mandati plans to lend support to General Garibaldi and Italian reunification. Garibaldi had asked for financing and volunteers from around the world as he launched his Redshirts in July 1860 to invade Sicily and conquer the Kingdom of Naples for annexation to what would finally become the newly-born Kingdom Of Italy with King Victor Emmanuel II.[39]

Monuments

-

Plaque dedicated to Garibaldi in Portovenere, Italy

-

Equestrian statue representing Garibaldi, La Spezia, Italy. It's one of the few statues where the horse is in a rampant position, even on a single leg.

-

Ettore Ferrari: Monument to Giuseppe Garibaldi Rovigo

-

Monument to Garibaldi (Rome). Picture postcard, 1910

-

Plaza Italia, from Parco Independencia, Argentina

-

Rosario, Argentina

-

Garden of Giuseppe Garibaldi Hospital. Work of Erminio Blotta, Rosario, Argentina

-

Praça Central at São José do Norte, Brazil

-

Garibaldi and Anita memorialized in Praça Garibaldi, Azenha, Porto Alegre, Brazil

-

Sofia, Bulgaria

-

Garibaldi Statue in Dijon, France

-

Garibaldi Square in Nice, France

-

Statue of Garibaldi in Cambronne Square, Paris, France

-

Budapest, Hungary

-

Taganrog, Russia

-

The first monument dedicated to Garibaldi, work of Stefano Galletti, 1882, San Marino

-

Plaque dedicated to Garibaldi Istanbul, Turkey

-

A statue of Garibaldi erected in Washington Square Park in New York City, US

-

Salto, Uruguay

In popular culture

Garibaldi is a major character in two juvenile historical novels by Geoffrey Trease: Follow My Black Plume and A Thousand for Sicily. They are both closely based on G. M. Trevelyan's accounts, the former set in the Roman Republic. Garibaldi is played by Raf Vallone in the 1952 film Red Shirts, by Renzo Ricci in the 1961 film Garibaldi, and by Giorgio Pasotti in the 2012 miniseries Anita Garibaldi. Garibaldi was one of the most important characters of A Casa das Sete Mulheres, a Brazilian serial of 2003, in which he was portrayed by Thiago Lacerda.

Photos and prints of Garibaldi

-

Portrait of General Giuseppe Garibaldi, published by Vanity Fair on 15 June 1878,

-

Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1875, pictured with (left to right): his daughter Clelia, his wife Francesca Armosino, his grandchild Manlio and his son Menotti.

-

Garibaldi is asked to halt the campaign in Trentino

-

Giuseppe and Anita Garibaldi fleeing to San Marino.

-

Garibaldi and his wife, Anita, defending Rome in 1849

-

Third War of Independence - Garibaldi organising troops during the Battle of Bezzecca

-

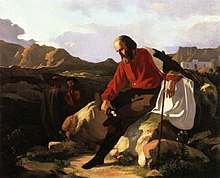

Garibaldi oil on canvas portrait by A. Zanieri. Located in the National Historic Museum - House of Joseph Garibaldi, Montevideo, Uruguay

-

Garibaldi oil on canvas portrait by Cayetano Gallino. Located in the National Historic Museum - House of Joseph Garibaldi, Montevideo, Uruguay

-

Garibaldi lithograph by Luigi Micheloni. Located in the National Historic Museum - House of Joseph Garibaldi, Montevideo, Uruguay

-

Garibaldi oil on canvas portrait. Located in the National Historic Museum - House of Joseph Garibaldi, Montevideo, Uruguay

Family tree

| Giuseppe Garibaldi | Anita Garibaldi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Menotti | Rosita | Teresita | Ricciotti Garibaldi | Harriet Constance Hopcraft | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peppino | Constantino | Anita | Ezio | Bruno Garibaldi | Unknown Son | Unknown Son | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Unità d'Italia: Giuseppe Garibaldi, l'eroe dei due mondi". Sapere.it (in Italian).

- ^ Scirocco 2011, p. 3

- ^ Baptismal record: "Die 11 d.i (giugno 1766) Dominicus Antonina Filius Angeli Garibaldi q. Dom.ci et Margaritae Filiae q. Antonij Pucchj Coniugum natus die 9 huius et hodie baptizatus fuit a me Curato Levantibus Io. Bapta Pucchio q. Antonij, et Maria uxore Agostini Dassi. (Chiavari, Archive of the Parish Church of S. Giovanni Battista, Baptismal Record, vol. n. 10 (dal 1757 al 1774), p. 174).

- ^ (often wrongly reported as Raimondi, but Status Animarum and Death Records all report the same name "Raimondo") Baptismal record from the Parish Church of S. Giovanni Battista in Loano: "1776, die vigesima octava Januarij. Ego Sebastianus Rocca praepositus hujus parrochialis Ecclesiae S[anct]i Joannis Baptistae praesentis loci Lodani, baptizavi infantem natam ex Josepho Raimimdi q. Bartholomei, de Cogoleto, incola Lodani, et [Maria] Magdalena Conti conjugibus, cui impositum est nomen Rosa Maria Nicolecta: patrini fuerunt D. Nicolaus Borro q. Benedicti de Petra et Angela Conti Joannis Baptistae de Alessio, incola Lodani." " Il trafugamento di Giuseppe Garibaldi dalla pineta di Ravenna a Modigliana ed in Liguria, 1849, di Giovanni Mini, Vicenza 1907 – Stab. Tip. L. Fabris.

- ^ a b Kleis, Sascha M. (2012). "Der Löwe von Caprera" [The Lion of Caprera]. Damals (in German) (6): 57–59.

- ^ Garibaldi – the mason Translated from Giuseppe Garibaldi Massone by the Grand Orient of Italy

- ^ a b http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/biography/garibaldi_g/garibaldi.html "Garibaldi — the mason". Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon A.F. & A. M., 2003.

- ^ A. Werner, Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi, Vol. III, Howard Fertig, New York (1971) p. 68.

- ^ G. M. Trevelyan,Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic, Longmans, London (1907) p. 227

- ^ a b c d e f g Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1889). Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi. Walter Smith and Innes. pp. 54–69.

- ^ a b Jackson, Kenneth T. (1995). The Encyclopedia of New York City. The New York Historical Society and Yale University Press. p. 451.

- ^ http://openplaques.org/plaques/8453

- ^ Bell, David. Ships, Strikes and Keelmen: Glimpses of North-Eastern Social History, 2001 ISBN 1-901237-26-5

- ^ Hibbert, Christopher. Garibaldi and His Enemies. New York: Penguin Books, 1987. p.171

- ^ Shepard B. Clough et al., A History of the Western World (1964) p. 948

- ^ Mack Smith, pp. 69-70

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 70

- ^ Mack Smith, p. 72

- ^ Donald M. MacRaild (2010). The Irish Diaspora in Britain, 1750-1939. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 178–79.

- ^ For his role in the United States, see

- ^ Don H. Doyle, The Cause of All Nations: An International History of the American Civil War (New York: Basic Books, 2015), 226-33.

- ^ Laurenza,Vincenzo (2003). "Victorian Sensation". Anthem Press. pp. 50–53. ISBN 1-84331-150-X.

- ^ Diamond, Michael (1932). Garibaldi a Malta (PDF). B. Cellini. pp. 143–161.

- ^ "Visit of Garibaldi to the Britannia Iron Works, 1864". Bedford Borough Council. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Giuseppe Guerzoni, Garibaldi: con documenti editi e inediti, Florence, 1882, Vol. 11, 485.

- ^ Ridley, p. 602

- ^ Ridley, p. 633

- ^ "Giuseppe Garibaldi's body to be exhumed in Italy". BBC News. 26 July 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ^ Alan Johnston (14 January 2013). "Garibaldi: Is his body still in its tomb?". BBC News.

- ^ Garibaldi, Giuseppe (1889). Autobiography.

- ^ Garibaldi, Giuseppe; Alexandre Dumas, père (1861). The Memoirs of Garibaldi.

- ^ Sinistra costituzionale, correnti democratiche e società italiana dal 1870 al 1892: atti del XXVII Convegno storico toscano (Livorno, 23–25 settembre 1984). L. S. Olschki. 1988. ISBN 978-88-222-3609-8. Retrieved 21 February 2011.

- ^ [2]

- ^ David Cannadine, "Trevelyan, George Macaulay (1876–1962)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 accessed 5 Nov 2017

- ^ "History of Nottingham Forest" nottinghamforest.co.uk

- ^ "The Garibaldi School". Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ Denis Mack Smith (Editor), Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed), Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, N.J. (1969) p. 76

- ^ "Zane Grey Theatre: "Guns for Garibaldi", February 18, 1960". Internet Movie Data Base. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

Further reading

- Garibaldi, Giuseppe; Dumas, Alexandre (1861). Garibaldi: an autobiography. Routledge.

- Hughes-Hallett, Lucy (2004). Heroes: A History of Hero Worship. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4399-9.

- Marraro, Howard R. "Lincoln’s Offer of a Command to Garibaldi: Further Light on a Disputed Point of History." Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 36#3 (1943): 237-270

- Riall, Lucy. The Italian Risorgimento: State, Society, and National Unification (Routledge, 1994) online

- Riall, Lucy. Garibaldi: Invention of a hero (Yale UP, 2008).

- Riall, Lucy. "Hero, saint or revolutionary? Nineteenth-century politics and the cult of Garibaldi." Modern Italy 3.02 (1998): 191-204.

- Riall, Lucy. "Travel, migration, exile: Garibaldi's global fame." Modern Italy 19.1 (2014): 41-52.

- Ridley, Jasper. Garibaldi (1974), a standard biography.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1969). Garibaldi (Great Lives Observed). Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice Hall.

- Trevelyan, George Macaulay (1911). Garibaldi and the making of Italy.

- Trevelyan, George Macaulay. Garibaldi and the Thousand.

- Trevelyan, George Macaulay. Garibaldi's Defence of the Roman Republic.

- Werner, A. (1971). Autobiography of Giuseppe Garibaldi Vol. I, II, III. New York: Howard Fertig.

External links

- Garibaldi and the Volturnus' battle

- Works by Giuseppe Garibaldi at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Giuseppe Garibaldi at the Internet Archive

- Garibaldi & the Risorgimento – Brown University

- Brown University Library Original water-color panorama 273 ft in long painted around 1860 depicting the life and campaigns of Garibaldi

- The Giuseppe Garibaldi Foundation

- 1867 Caricature of Garibaldi by André Gill

- i Mille Garibaldini Template:It icon

- il Patriota dei Mille: Paolo Bovi Campeggi Template:It icon

- Review of Lucy Riall's Garibaldi: The Invention of a Hero

- "Mio Padre" by Clelia Garibaldi Book's web site Template:It icon

- The most beautiful walk in the world named after Anita Garibaldi: Genoa, Italy

- "That bronze of Garibaldi in New York Village …a long story", by Tiziano Thomas Dossena, bridgepugliausa.it, 2012

- Use dmy dates from May 2012

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- 1807 births

- 1882 deaths

- 19th-century Italian novelists

- Carbonari

- Critics of the Catholic Church

- Freemen of the City of London

- Italian deists

- Italian expatriates in Brazil

- Italian expatriates in Uruguay

- Italian Freemasons

- Italian generals

- Italian irredentism

- Italian male novelists

- Italian mercenaries

- Italian military leaders

- Italian nationalists

- Italian people of the Italian unification

- Italian Protestants

- Italian revolutionaries

- Italian sailors

- Masonic Grand Masters

- Members of the Expedition of the Thousand

- Members of the Senate of the Kingdom of Italy

- Military history of Italy

- People from Nice

- People from the Kingdom of Sardinia

- People of Ligurian descent

- People of the American Civil War

- People of the Franco-Prussian War

- People of the Revolutions of 1848

- People sentenced to death in absentia

- Political history of France

- Political history of Italy

- Writers from Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur