Goth subculture

The goth subculture is a contemporary subculture found in many countries. It began in England during the early 1980s in the gothic rock scene, an offshoot of the post-punk genre. Notable post-punk groups that presaged that genre are Siouxsie and the Banshees, Joy Division and Bauhaus. The goth subculture has survived much longer than others of the same era, and has continued to diversify. Its imagery and cultural proclivities indicate influences from the 19th century Gothic literature along with horror films.

The goth subculture has associated tastes in music, aesthetics, and fashion. The music of the goth subculture encompasses a number of different styles, including gothic rock, industrial, deathrock, post-punk, darkwave, ethereal wave, neoclassical, and gothic metal. Styles of dress within the subculture range from deathrock, punk and Victorian styles, or combinations of the above, most often with dark attire (often black), pale face makeup and black hair. The scene continues to draw interest from a large audience decades after its emergence. In Western Europe, there are large annual festivals, mainly in Germany.

Music

Origins and development

The term "gothic rock" was coined in 1967 by music critic John Stickney to describe a meeting he had with Jim Morrison in a dimly lit wine-cellar which he called "the perfect room to honor the Gothic rock of the Doors".[1] That same year, Velvet Underground with a track like "All Tomorrow's Parties", created a kind of "mesmerizing gothic-rock masterpiece" according to music historian Kurt Loder.[2] In the late 1970s, the "gothic" adjective was used to describe the atmosphere of post-punk bands like Siouxsie and the Banshees, Magazine and Joy Division. In a live review about a Siouxsie and the Banshees' concert in July 1978, critic Nick Kent wrote that concerning their music, "parallels and comparisons can now be drawn with gothic rock architects like the Doors and, certainly, early Velvet Underground".[3] In March 1979, in his review of Magazine's second album Secondhand Daylight, Kent noted that there was "a new austere sense of authority" in the music, with a "dank neo-Gothic sound".[4] Later that year, the term was also used by Joy Division's manager, Tony Wilson on 15 September in an interview for the BBC TV programme's Something Else: Wilson described Joy Division as "gothic" compared to the pop mainstream, right before a live performance of the band.[5] The term was later applied to "newer bands such as Bauhaus who had arrived in the wake of Joy Division and Siouxsie and the Banshees".[6] Bauhaus's first single issued in 1979, "Bela Lugosi's Dead", is generally credited as the starting point of the gothic rock genre.[7]

In 1979, Sounds described Joy Division as "Gothic" and "theatrical".[8] In February 1980, Melody Maker qualified the same band as "masters of this Gothic gloom".[9] Critic Jon Savage would later say that their singer Ian Curtis wrote "the definitive Northern Gothic statement".[10] However, it was not until the early 1980s that gothic rock became a coherent music subgenre within post-punk, and that followers of these bands started to come together as a distinctly recognisable movement. They may have taken the "goth" mantle from a 1981 article published in UK rock weekly Sounds: "The face of Punk Gothique",[11] written by Steve Keaton. In a text about the audience of UK Decay, Keaton asked: "Could this be the coming of Punk Gothique? With Bauhaus flying in on similar wings could it be the next big thing?".[11] In July 1982, the opening of the Batcave in London's Soho provided a prominent meeting point for the emerging scene, which would be briefly labelled "positive punk" by the NME in a special issue with a front cover in early 1983.[12] The term "Batcaver" was then used to describe old-school goths.

Independent from the British scene, in the late 1970s and early 1980s in California, deathrock developed as a distinct branch of American punk rock, with acts such as Christian Death and 45 Grave.[13] Another genre which had gothic rock's "dark, morbid, and otherworldly leanings" was horror punk, exemplified by the Misfits,[14] a band formed in New Jersey in 1977.

Lauren M. E. Goodlad and Michael Bibby, two professors of English who have studied the Goth subculture, trace the origin of the genre to the situation of the United Kingdom in the late 1970s. The country was undergoing a socioeconomic decline and Thatcherism had emerged in the political scene.[15] The Punk subculture had already developed, drawing influences from several older subcultures and art movements such as Dada and garage rock. Punk had a considerable influence in the youth culture. It had introduced a DIY ethic towards music, its own distinct fashion, and an active contempt for "mainstream", mass-marketed music. Goth music was one of several new genres and subgenres to emerge from the Punk music and culture, and inherited aspects of its ancestor. But it also differed from punk in several ways.[15]

Punk music embraced "crass and trashy" as part of their aesthetic, though there were aspects of Romanticism in the movement. Goth embraced Romanticism itself. It drew from it a preference for the dreadful and the macabre.[15] Siouxsie Sioux popularized a look based on "deathly pallor", "dark makeup", influences from the so-called decadence of the Weimar Republic, and from Nazi chic.[15] Punk embraced anarchy with a militant passion. Goth instead focused on "death, darkness and perverse sexuality".[15] The ideal male figure for Punk was often rigid, while for Goth it was androgynous.[15]

Gothic genre

The bands that defined and embraced the gothic rock genre included Bauhaus, [16] early Adam and the Ants,[17] The Cure,[18] The Birthday Party,[19] Southern Death Cult, Specimen, Sex Gang Children, UK Decay, Virgin Prunes, Killing Joke and the later incarnations of The Damned.[20] Near the peak of this first generation of the gothic scene in 1983, The Face's Paul Rambali recalled that there were "several strong Gothic characteristics" in the music of Joy Division.[21] In 1984, Joy Division's bassist Peter Hook named Play Dead as one of their heirs:

If you listen to a band like Play Dead, who I really like, Joy Division played the same stuff that Play Dead are playing. They're similar.[22]

By the mid-1980s, bands began proliferating and became increasingly popular, including The Sisters of Mercy, The Mission (known as The Mission UK in the U.S.), Alien Sex Fiend, The March Violets, Xmal Deutschland The Membranes and Fields of Nephilim. Record labels like Factory, 4AD and Beggars Banquet released much of this music in Europe, while Cleopatra, among others, released the music in the U.S., where the subculture grew, especially in New York and Los Angeles, California, where many nightclubs featured "gothic/industrial" nights. The popularity of 4AD bands resulted in the creation of a similar U.S. label, Projekt, which produces what was colloquially termed ethereal wave, a subgenre of dark wave music. [citation needed]

The 1990s saw further growth for some 1980s bands and the emergence of many new acts. According to Dave Simpson of The Guardian, "in the 90s, goths all but disappeared as dance music became the dominant youth cult."[23] As a result, the goth "movement went underground and mistaken for cyber goth, Shock rock, Industrial metal, Gothic metal, Medieval folk metal and the latest subgenre, horror punk."[23] During this period, around the world "goth hit the mainstream" and "goth crossbred with electronica and heavy metal in the form of Depeche Mode, Skinny puppy, Nine Inch Nails and Marilyn Manson."[14]

Art: historical and cultural influences

The Goth subculture of the 1980s drew inspiration from a variety of sources. Some of them were modern or contemporary, others were centuries-old or ancient. Lauren M. E. Goodlad and Michael Bibby liken the subculture to a bricolage[15] Among the music subcultures that influenced it were Punk, New wave, and Glam.[15] But it also drew inspiration from B movies, Gothic literature, Horror films, Vampire cults, and traditional mythology. Among the mythologies that proved influential in Goth were the Celtic mythology, Christian mythology, Egyptian mythology, various traditions of Paganism.[15]

The figures that the movement counted among its historic canon of ancestors were equally diverse. They included the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), Comte de Lautréamont (1846-1870), Salvador Dalí (1904-1989), Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), and The Velvet Underground.[15] Writers that have had a significant influence on the movement also represent a diverse canon. They include Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), John William Polidori (1795-1821), Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), Sheridan Le Fanu (1814-1873), Bram Stoker (1847-1912), Oscar Wilde (1854-1900), H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), Anne Rice (1941-), William Gibson (1948-), Ian McEwan (1948-), Storm Constantine (1956-), and Poppy Z. Brite (1967-).[15]

18th and 19th centuries

Gothic literature is a genre of fiction that combines romance and dark elements to produce mystery, suspense, terror, horror and the supernatural. According to David H. Richter, settings were framed to take place at “…ruinous castles, gloomy churchyards, claustrophobic monasteries, and lonely mountain roads.” Typical characters consisted of the cruel parent, sinister priest, courageous victor, and the helpless heroine, along with supernatural figures such as demons, vampires, ghosts, and monsters. Often, the plot focused on characters ill-fated, internally conflicted, and innocently victimized by harassing malicious figures. In addition to the dismal plot focuses, the literary tradition of the gothic was to also focus on individual characters that were gradually going insane.[24]

English author Horace Walpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto is one of the first writers who explored this genre. The American Revolutionary War-era "American Gothic" story of the Headless Horseman, immortalized in "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" (published in 1820) by Washington Irving, marked the arrival in the New World of dark, romantic storytelling. The tale was composed by Irving while he was living in England, and was based on popular tales told by colonial Dutch settlers of the Hudson Valley, New York. The story would be adapted to film in 1922 and 1949 in the animated The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad.[citation needed]

Throughout the evolution of the goth subculture, classic romantic, Gothic and horror literature has played a significant role. E.T.A. Hoffmann (1776–1822), Edgar Allan Poe[25] (1809–1849), Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867),[25] H. P. Lovecraft (1890–1937), and other tragic and romantic writers have become as emblematic of the subculture [citation needed] as the use of dark eyeliner or dressing in black. Baudelaire, in fact, in his preface to Les Fleurs du mal (Flowers of Evil) penned lines that could serve as a sort of goth malediction:[citation needed]

C'est l'Ennui! —l'œil chargé d'un pleur involontaire,

Il rêve d'échafauds en fumant son houka.

Tu le connais, lecteur, ce monstre délicat,

—Hypocrite lecteur,—mon semblable,—mon frère!

It is Boredom! — an eye brimming with an involuntary tear,

He dreams of the gallows while smoking his water-pipe.

You know him, reader, this fragile monster,

—Hypocrite reader,—my twin,—my brother!

Visual art influences

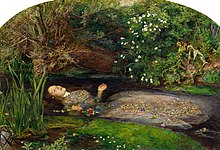

The gothic subculture has influenced different artists—not only musicians—but also painters and photographers. In particular their work is based on mystic, morbid and romantic motifs. In photography and painting the spectrum varies from erotic artwork to romantic images of vampires or ghosts. There is a marked preference for dark colours and sentiments, similar to Gothic fiction. At the end of the 19th century, painters like John Everett Millais and John Ruskin invented a new kind of Gothic.[26]

20th century influences

By the 1960s, television series such as The Addams Family and The Munsters used Gothic-derived stereotypes for camp comedy. The Byronic hero, in particular, was a key precursor to the male goth image [citation needed], while Dracula's iconic portrayal by Bela Lugosi appealed powerfully to early goths[citation needed]. They were attracted by Lugosi's aura of camp menace, elegance and mystique. Some people credit the band Bauhaus' first single "Bela Lugosi's Dead", released in August 1979, with the start of the goth subculture,[7] though many prior arthouse movements influenced gothic fashion and style, the illustrations and paintings of Swiss artist H. R. Giger being one of the earliest[citation needed].

A prominent American literary influence on the gothic scene was provided by Anne Rice’s re-imagining of the vampire in 1976. In The Vampire Chronicles, Rice’s characters were depicted as self-tormentors who struggled with alienation, loneliness, and the human condition. Not only did the characters torment themselves, but they also depicted a surreal world that focused on uncovering its splendor. These Chronicles assumed goth attitudes, but they were not intentionally created to represent the gothic subculture. Their romance, beauty, and erotic appeal attracted many goth readers, making her works popular from the 1980s through the 1990s.[27]

While Goth has embraced Vampire literature both in its 19th century form and in its later incarnations, Rice's postmodern take on the vampire mythos has had a "special resonance" in the subculture. Her vampire novels feature intense emotions, period clothing, and "cultured decadence". Her vampires are socially alienated monsters, but they are also stunningly attractive. Rice's goth readers tend to envision themselves in much the same terms and view characters like Lestat de Lioncourt as role models.[15]

Characteristics of the scene

Icons

Notable examples of goth icons include several bandleaders: Siouxsie Sioux of Siouxsie and the Banshees, Robert Smith of The Cure, Peter Murphy of Bauhaus and Dave Vanian of The Damned. Some members of Bauhaus were, themselves, fine art students or active artists. Nick Cave was dubbed as "the grand lord of gothic lushness".[28] Nico is also a notable icon of goth fashion and music, with pioneering records like The Marble Index and Desertshore and the persona she adopted after their release.

Fashion

Gothic fashion is stereotyped as conspicuously dark, eerie, mysterious, complex and exotic.[29] Goth fashion can be recognized by its stark black clothing.Typical gothic fashion includes dyed black hair, dark eyeliner, black fingernails and black period-styled clothing; goths may or may not have piercings. Styles are often borrowed from the Elizabethan, Victorian or medieval period and often express pagan, occult or other religious imagery.[30]

Ted Polhemus described goth fashion as a "profusion of black velvets, lace, fishnets and leather tinged with scarlet or purple, accessorized with tightly laced corsets, gloves, precarious stilettos and silver jewelry depicting religious or occult themes".[31] Researcher Maxim W. Furek stated that "Goth is a revolt against the slick fashions of the 1970s disco era and a protest against the colorful pastels and extravagance of the 1980s. Black hair, dark clothing and pale complexions provide the basic look of the Goth Dresser. One can paradoxically argue that the Goth look is one of deliberate overstatement as just a casual look at the heavy emphasis on dark flowing capes, ruffled cuffs, pale makeup and dyed hair demonstrate a modern-day version of late Victorian excess.[32] Gothic fashion may also feature silver jewelry.

The New York Times noted: "The costumes and ornaments are a glamorous cover for the genre's somber themes. In the world of Goth, nature itself lurks as a malign protagonist, causing flesh to rot, rivers to flood, monuments to crumble and women to turn into slatterns, their hair streaming and lipstick askew".[29] Present-day fashion designers such as John Paul Gaultier,[29] Alexander McQueen, and John Galliano have also been described as practising "haute goth".[33]

Films

Some of the early gothic rock and deathrock artists adopted traditional horror film images and drew on horror film soundtracks for inspiration. Their audiences responded by adopting appropriate dress and props. Use of standard horror film props like swirling smoke, rubber bats, and cobwebs featured as gothic club décor from the beginning in The Batcave. Such references in bands' music and images were originally tongue-in-cheek, but as time went on, bands and members of the subculture took the connection more seriously. As a result, morbid, supernatural and occult themes became more noticeably serious in the subculture. The interconnection between horror and goth was highlighted in its early days by The Hunger, a 1983 vampire film starring David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon. The film featured gothic rock group Bauhaus performing Bela Lugosi's Dead in a nightclub. Tim Burton created a storybook atmosphere filled with darkness and shadow in some of his films like Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989), Edward Scissorhands (1990), and the stop motion films Nightmare Before Christmas (1993), which was produced/co-written by Burton, and Corpse Bride (2005), which he co-produced.

As the subculture became well-established, the connection between goth and horror fiction became almost a cliché, with goths quite likely to appear as characters in horror novels and film. For example, The Crow, The Matrix and Underworld film series drew directly on goth music and style. The dark comedy Beetlejuice, The Faculty, American Beauty, Wedding Crashers and a few episodes of South Park portray or parody the goth subculture.

Books and magazines

The re-imagining of the vampire continued with the release of Poppy Z. Brite's book Lost Souls in October 1992. Despite the fact that Brite's first novel was criticized by some mainstream sources for allegedly "lack[ing] a moral center: neither terrifyingly malevolent supernatural creatures nor (like Anne Rice's protagonists) tortured souls torn between good and evil, these vampires simply add blood-drinking to the amoral panoply of drug abuse, problem drinking and empty sex practiced by their human counterparts",[34] many of these so-called "human counterparts" identified with the teen angst and goth music references therein, keeping the book in print. Upon release of a special 10th anniversary edition of Lost Souls, Publishers Weekly—the same periodical that criticized the novel's "amorality" a decade prior—deemed it a "modern horror classic" and acknowledged that Brite established a "cult audience".[35]

Neil Gaiman's acclaimed graphic novel series The Sandman influenced goths with characters like the dark, brooding Dream and his sister Death.

The 2002 release 21st Century Goth by Mick Mercer, an author, noted music journalist and leading historian of goth music,[36][37][38] explored the modern state of the goth scene around the world, including South America, Japan, and mainland Asia. His previous 1997 release, Hex Files: The Goth Bible, similarly took an international look at the subculture.

In the US, Propaganda was a gothic subculture magazine founded in 1982. In Italy, Ver Sacrum covers the Italian goth scene, including fashion, sexuality, music, art and literature. Some magazines, such as the now-defunct Dark Realms[39] and Goth Is Dead included goth fiction and poetry. Other magazines cover fashion (e.g., Gothic Beauty); music (e.g., Severance) or culture and lifestyle (e.g., Althaus e-zine).

Graphic art

Visual contemporary graphic artists with this aesthetic include Gerald Brom, Luis Royo, Dave McKean, Trevor Brown, Victoria Francés as well as the American comic artist James O'Barr. H. R. Giger of Switzerland is one of the first graphic artists to make serious contributions to the gothic/industrial look of much of modern cinema with his work on the 1979 film Alien by Ridley Scott. The artwork of Polish surrealist painter Zdzisław Beksiński is often described as gothic.[citation needed] British artist Anne Sudworth published a book on gothic art in 2007.[40]

Events

The goth scene continues to exist in the 2010s. In Western Europe, there are large annual festivals mainly in Germany, including Wave-Gotik-Treffen (Leipzig) and M'era Luna (Hildesheim), both annually attracting tens of thousands of attendees. The Lumous Gothic Festival (more commonly known as Lumous) is the largest festival dedicated to the goth subculture in Finland and the northernmost gothic festival in the world. The Ukrainian festival "Deti Nochi: Chorna Rada" (Children of the night) is the biggest gothic event in the Ukraine. Goth events like "Ghoul School" and "Release the Bats" promote deathrock and are attended by fans from many countries, and events such as the Drop Dead Festival attract attendees from over 30 countries. The Whitby Goth Weekend is a twice-yearly goth music festival in Whitby, North Yorkshire, England.

Gender and sexuality

Since the late 1970s, the UK goth scene refused "traditional standards of sexual propriety" and accepted and celebrated "unusual, bizarre or deviant sexual practices." [41] Observers have noted changes in the subculture, such as the "increasing incorporation of S-M sexual practices and fetish culture" in the goth scene.[42] Another aspect of the goth subculture is the "...ambivalence of gothic androgynous practice."[43] The goth subculture is "...equally open to women, men, and transgender people."[44] Dunja Brill's Goth Culture: Gender, Sexuality and Style argues that "...androgyny in Goth subcultural style often disguises or even functions to reinforce conventional gender roles." She found that androgyny was only "valorised" for male goths, who adopt a "feminine" appearance, including "make-up, skirts and feminine accessories" to "enhance masculinity" and facilitate traditional heterosexual courting roles. [45]

Identity

Several observers have raised the issue of to what degree individuals are truly members of the goth subculture. On one end of the spectrum is the "Uber goth", a person who is described as seeking a pallor so much that he or she applies "...as much white foundation and white powder as possible."[46] On the other end of the spectrum another writer terms "poseurs": "goth wannabes, usually young kids going through a goth phase who do not hold to goth sensibilities but want to be part of the goth crowd..."[47] It has been said that a "mall goth" is a teen who dresses in a goth style and spends time in malls with a Hot Topic store, but who does not know much about the goth subculture or its music, thus making him or her a poseur.[48] In one case, even a well-known performer has been labeled with the pejorative term: a "number of goths, especially those who belonged to this subculture before the late 1980s, reject Marilyn Manson as a poseur who undermines the true meaning of goth."[49]

Media and academic commentary

The Guardian reported that a "glue binding the [goth] scene together was drug use"; however, in the goth scene drug use was varied. Goth is one of the few youth movements that is not associated with a single drug.[50]

The BBC described academic research that indicated that goths are "refined and sensitive, keen on poetry and books, not big on drugs or anti-social behaviour."[51] Teens who are goths will probably stay in the subculture "into their adult life", and they are likely to become well-educated and enter professions such as medicine or law.[51] Dr. Lynne E. Ponton, an adolescent psychiatrist at University of California at San Francisco, says that the goth subculture "appeals to teenagers who are looking for meaning and for identity." She points out that the goth scene teaches teens that there are difficult aspects to life that you "have to make an attempt to understand" or explain.[52]

Ideology

Defining an explicit ideology for the gothic subculture is difficult for several reasons. First is the overwhelming importance of mood and aesthetic for those involved. This is, in part, inspired by romanticism and neoromanticism. The allure for goths of dark, mysterious, and morbid imagery and mood lies in the same tradition of Romanticism's gothic novel. During the late 18th and 19th century, feelings of horror, and supernatural dread were widespread motifs in popular literature; The process continues in the modern horror film. Balancing this emphasis on mood and aesthetics, another central element of the gothic is a deliberate sense of camp theatricality and self-dramatization; present both in gothic literature as well as in the gothic subculture itself.

Goths, in terms of their membership in the subculture, are usually not supportive of violence, but are tolerant of alternative lifestyles that incorporate themes such as BDSM—always involving consent. Violence and hate do not form elements of goth ideology; rather, the ideology is formed in part by recognition, identification, and grief over societal and personal evils that the mainstream culture wishes to ignore or forget. These are the prevalent themes in goth music.[53]

The second impediment to explicitly defining a gothic ideology is goth's generally apolitical nature. While individual defiance of social norms was socially risky in the 19th century, today it is far less socially radical. Thus, the significance of goth's subcultural rebellion is limited, and it draws on imagery at the heart of Western culture. Unlike the hippie or punk movements, the goth subculture has no pronounced political messages or cries for social activism. The subculture is marked by its emphasis on individualism, tolerance for diversity, a strong emphasis on creativity, tendency toward intellectualism, and a mild tendency towards cynicism, but even these ideas are not universal to all goths. Goth ideology is based far more on aesthetics and simplified ethics than politics.

Goths may, indeed, have political leanings ranging from left-wing to right-wing, but they do not express them specifically as part of a cultural identity. Instead, political affiliation, like religion, is seen as a matter of personal conscience. Unlike punk, there are few clashes between political affiliation and being "goth". Similarly, there is no common religious tie that binds together the goth movement, though spiritual, supernatural, and religious imagery has played a part in gothic fashion, song lyrics and visual art. In particular, aesthetic elements from Catholicism often appear in goth culture. Reasons for donning such imagery range from expression of religious affiliation to satire or simply decorative effect. Regardless, there is a general tolerance for religious beliefs, and everyone including strict Catholics, atheists, and polytheists are accepted.[53]

While involvement with the subculture can be fulfilling, it also can be risky depending on where the goth lives, especially for the young, because of the negative attention it can attract due to public misconceptions of goth subculture. The value that young people find in the movement is evinced by its continuing existence after other subcultures of the 1980s (such as the New Romantics) have died out.

Media perceptions on violence and self-harm

The gothic fascination with the macabre has led media critics to question the psychological well-being of goths. The mass media have made reports that have influenced the public view that goths, or people associated with the subculture, are malicious or Satan-worshippers. Contrary to these perceptions, the goth subculture is often described as non-violent.[54] However, two non peer-reviewed studies by the A.S.H.A.[who?] concluded a higher than average propensity toward violence, and for one of the papers, self-harm, within the subculture.[55][56] Some individuals who have either identified themselves or been identified by others as goth have committed high profile violent crimes, including several school shootings. These incidents and their attribution to the goth scene have helped to propagate a wary perception of goth in the public eye.[30][57]

Violence attributed to goths

Public concern with the goth subculture reached a high point in the fallout of the Columbine High School massacre that was carried out by two students, incorrectly associated with the goth subculture. This misreporting of the roots of the massacre caused a widespread public backlash against the North American goth scene. Investigators of the incident, five months later, stated that the killers, who held goth music in contempt, were not involved with the goth subculture.[58]

The Dawson College shooting, in Canada, also raised public concern with the goth scene. Kimveer Gill, who killed one and injured 19, maintained an online journal at a web site, VampireFreaks, in which he "portrayed himself as a gun-loving Goth."[59] The day after the shooting, it was reported that "it are rough times for industrial / goth music fans these days as a result of yet another trench coat killing", implying that Gill was involved in the goth subculture.[59] During a search of Gill's home, police found a letter praising the actions of Columbine shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold and a CD titled "Shooting sprees ain't no fun without Ozzy and friends LOL".[60] Although the shooter claimed an obsession for "goth", his favorite music list was described, by the media, as a "who's who of heavy metal.[61][62]

Mick Mercer stated, of Kimveer Gill, that he was "not a Goth. Never a Goth. The bands he listed as his chosen form of ear-bashing were relentlessly metal and standard grunge, rock and Goth metal, with some industrial presence.", "Kimveer Gill listened to metal." "He had nothing whatsoever to do with Goth," and further commented "I realise that like many Neos this idiot may even have believed he somehow was a Goth, because they're only really noted for spectacularly missing the point." Mercer emphasized that he was not blaming heavy metal music for Gill's actions and added "It doesn't matter actually what music he liked."[63]

Another school shooting that was wrongly attributed to the goth subculture is the Red Lake High School shooting.[64] Jeff Weise killed seven people, and was believed by a fellow student to be into the goth culture: wearing "a big old black trench coat," and listening to heavy metal music (as opposed to gothic rock). Weise was also found to participate in neo-nazi online forums.[65]

Other murders which are attributed to people suspected of being part of the goth culture include the Scott Dyleski killing,[66] and the Richardson family murders,[67] and the "Medicine Hat killings"[68] although neither of these cases raised the same amount of media attention as the school shootings.

Violence against goths

In part because of public misunderstanding and ignorance surrounding gothic aesthetics, goths sometimes suffer prejudice, discrimination, and intolerance. As is the case with members of various other subcultures and alternative lifestyles, outsiders sometimes marginalize goths, either by intention or by accident.[69] Goths, like any other alternative subculture sometimes suffer intimidation, humiliation, and, in many cases, physical violence for their involvement with the subculture.[57]

In 2006, a Navy sailor, James Eric Benham, and his brother attacked four goths in San Diego California. One goth, Jim Howard, had to be rushed to the hospital. The perpetrators of this attack were found guilty in August 2007 on four related accounts, two of which were felonies, though Benham only spent 37 days in jail. During the trial, it was made clear that the goths were assaulted due to their subculture affiliation. This can be otherwise known as a "hate crime" though the San Diego courts did not recognize this attack as such at the time.[70][71][72]

On 11 August 2007, a couple walking through Stubbylee Park in Bacup, Lancashire, England were attacked by a group of teenagers because they were goths. Sophie Lancaster subsequently died from her injuries.[73] On 29 April 2008, two teens, Ryan Herbert and Brendan Harris, were convicted for the murder of Lancaster and given life sentences; three others were given lesser sentences for the assault on her boyfriend Robert Maltby. In delivering the sentence, Judge Anthony Russell stated, "This was a hate crime against these completely harmless people targeted because their appearance was different to yours." He went on to defend the goth community, calling goths "perfectly peaceful, law-abiding people who pose no threat to anybody."[74][75] Judge Russell added that he "recognised it as a hate crime without Parliament having to tell him to do so and had included that view in his sentencing."[76] Despite this ruling, a bill to add discrimination based on subculture affiliation to the definition of hate crime in British law was not presented to parliament.[77]

In 2008, Paul Gibbs, a Briton from Leeds, UK was attacked by three men. He and his group of about 20 young goths were on a camping trip in the vicinity of Rothwell when two 18-year-olds (Quinn Colley, Ryan Woodhead) and one 22-year-old (Andrew Hall) raided, stabbed four of the men and robbed two women. Colley had previously appeared in a homemade clip rapping about his love of violence.[78] Gibbs was offered a motorbike ride by the attackers, who at first insidiously befriended the group. On their way, they knocked Gibbs from the bike, rendered him unconscious with a helmet, and sliced off his ear. Afterwards, the attackers returned to the camp.

Colley and Woodhead were sentenced to at least 2½ years of prison while Hall at least 4½ years. Gibbs' ear was found 17 hours later, thus doctors could not immediately reattach it. Instead, they stitched it inside his abdomen with the hope that some of the tissue would regrow. The ear could be reconstructed by using cartilage removed from Gibbs' ribs.[79][80][81][82][83]

In 2013, police in Manchester announced they would be treating attacks on members of alternative subcultures, like goths, the same as they do for attacks based on race and religion.[84]

Self-harm study

A study published on the British Medical Journal concluded that "identification as belonging to the Goth subculture [at some point in their lives] was the best predictor of self harm and attempted suicide [among young teens]", and that it was most possibly due to a selection mechanism (persons that wanted to harm themselves later identified as goths, thus raising the percentage of those persons who identify as goths).[85] According to The Guardian, some goth teens are at more likely to harm themselves or attempt suicide. A medical journal study of 1,300 Scottish schoolchildren until their teen years found that the 53% of the goth teens had attempted to harm themselves and 47% had attempted suicide. The study found that the "correlation was stronger than any other predictor."[86] The study was based on a sample of 15 teenagers who identified as goths, of which 8 had self-harmed by any method, 7 had self-harmed by cutting, scratching or scoring, and 7 had attempted suicide.[87][88][89]

The authors held that most self-harm by teens was done before joining the subculture, and that joining the subculture would actually protect them and help them deal with distress in their lives.[88][89] The authors insisted on the study being based on small numbers and on the need of replication to confirm the results.[88][89] The study was criticized for using only a small sample of goth teens and not taking into account other influences and differences between types of goths ; by taking a study from a larger number of people.[90]

See also

- History of subcultures in the 20th century

- List of gothic rock bands

- Toronto goth scene

- Neo (nightclub)

Notes

- ^ John Stickney (24 October 1967). "Four Doors To The Future: Gothic Rock Is Their Thing". The Williams Record. Posted at "The Doors : Articles & Reviews Year 1967". Mildequator.com. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

"The Doors are not pleasant, amusing hippies proffering a grin and a flower; they wield a knife with a cold and terrifying edge. The Doors are closely akin to the national taste for violence, and the power of their music forces each listener to realize what violence is in himself."... "The Doors met New York for better or for worse at a press conference in the gloomy vaulted wine cellar of the Delmonico hotel, the perfect room to honor the Gothic rock of the Doors".

- ^ Loder, Kurt (December 1984). V.U. (album liner notes). Verve Records.

- ^ Kent, Nick. "Banshees make the Breakthrough [live review - London the Roundhouse 23 July 1978". NME (29 July 1978).

- ^ Kent, Nick. "Magazine's Mad Minstrels Gains Momentum (Album review)". NME (31 March 1979): 31.

- ^ "Something Else [featuring Joy Division]". BBC television [archive added on youtube]. 15 September 1979.

Because it is unsettling, it is like sinister and gothic, it won't be played. [interview of Joy Division's manager Tony Wilson next to Joy Division's drummer Stephen Morris from 3:31]

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 352.

- ^ a b Reynolds 2005, p. 432.

- ^ De Moines (26 October 1979). "Live review by Des Moines (Joy Division Leeds)". Sounds.

Curtis may project like an ambidextrous barman puging his physical hang-ups, but the 'Gothic dance music' he orchestrates is well-understood by those who recognise their New Wave frontiersmen and know how to dance the Joy Division! A theatrical sense of timing, controlled improvisation...

- ^ Bohn, Chris. "Northern gloom: 2 Southern stomp: 1. (Joy Division: University of London Union – Live Review)". Melody Maker (16 February 1980).

Joy Division are masters of this Gothic gloom

- ^ Savage, Jon (July 1994). "Joy Division: Someone Take These Dreams Away". Mojo via Rock's Backpages (subscription required). Retrieved 10 July 2014.

a definitive Northern Gothic statement: guilt-ridden, romantic, claustrophobic

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Keaton, Steve (21 February 1981). "The Face Of Punk Gothique". Sounds.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ North, Richard (19 February 1983). "Punk Warriors". NME.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Ohanesian, Liz (4 November 2009). "The LA Deathrock Starter Guide". L.A. Weekly. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ^ a b Hammer, Josh (31 October 2012). "Barbarian Void of Refinement: A Complete History of Goth". Vice.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Goodlad, Bibby (2007), p. 1-41

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 429.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 421.

- ^ Mason, Stewart. "Pornography – The Cure : Songs, Reviews, Credits, Awards : AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 431.

- ^ Reynolds 2005, p. 435.

- ^ Rambali, Paul. "A Rare Glimpse Into A Private World". The Face (July 1983).

Curtis' death wrapped an already mysterious group in legend. From the press eulogies, you would think Curtis had gone to join Chatterton, Rimbaud and Morrison in the hallowed hall of premature harvests. To a group with several strong Gothic characteristics was added a further piece of romance.

- ^ Houghton, Jayne. "Crime Pays!" (June 1984). ZigZag: 21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Simpson, Dave (29 September 2006). "Back in black: Goth has risen from the dead - and the 1980s pioneers are (naturally) not happy about it". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Richter, David H. (Spring 1987). "Gothic Fantasia: The Monsters and The Myths A Review- Article". The Eighteenth Century. 28. University of Pennsylvania Press: 149–170. JSTOR 41467717.

- ^ a b Simpson, Dave (29 September 2006). "Back in black: Goth has risen from the dead - and the 1980s pioneers are (naturally) not happy about it". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2014. "Severin admits his band (Siouxsie and the Banshees) pored over gothic literature - Edgar Allan Poe and Charles Baudelaire."

- ^ Spuybroek, Lars (2011). The Sympathy of Things: Ruskin and the Ecology of Design. V2_Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 9056628275.

- ^ Jones, Timothy (2015). "Every Day is Halloween- Goth and the Gothic". The Gothic and the Gothic Carnivalesque in American Culture. University of Wales. pp. 179–204.

- ^ Stevens, Jenny (15 February 2013). "Push The Sky Away". NME. Retrieved 21 February 2013.

- ^ a b c La Ferla, Ruth (30 October 2005). "Embrace the Darkness". New York Times. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- ^ a b Eric Lipton Disturbed Shooters Weren't True Goth from the Chicago Tribune, 27 April 1999

- ^ Polhemus 1994, p. 97

- ^ "The Death Proclamation of Generation X: A Self-Fulfilling Prophesy of Goth, Grunge and Heroin" by Maxim W. Furek. i-Universe, 2008. ISBN 978-0-595-46319-0

- ^ Wilson, Cintra (17 September 2008). "You just can't kill it". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ "firction reviews: Lost Souls by Poppy Z. Brite". publishersweekly.com. 31 August 1992. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Fiction review: The American Fantasy Tradition by Brian M. Thomsen". publishersweekly.com. 1 September 2002. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Blu Interview with Mick Mercer Starvox.net

- ^ Kyshah Hell Interview with Mick Mercer Morbidoutlook.com

- ^ Mick Mercer Broken Ankle Books

- ^ Dark Realms

- ^ Sudworth, Anne (2007). Gothic Fantasies: The Paintings of Anne Sudworth. AAPPL. ISBN 978-1-904332-56-5.

- ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. p. 380

- ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. P. 378

- ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. P. 18

- ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. P. 40

- ^ Spooner, Catherine (28 May 2009). "Goth Culture: Gender, Sexuality and Style". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. P. 36

- ^ Nancy Kilpatrick. Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined. St. Martin's Griffin, 2004, p. 24

- ^ Liisa Ladouceur. Encyclopedia Gothica. ECW Press: 2011

- ^ Lauren M. E. Goodlad, Michael Bibby. Goth: Undead Subculture. Duke University Press, 11 April 2007. P. 344

- ^ {{cite web − | url =http://www.theguardian.com/music/2006/sep/29/popandrock − | title =Goth has risen from the dead - and the 1980s pioneers are (naturally) not happy about it. − | last =Simpson − | first =Dave − | date =29 September 2006 − | website =http://www.theguardian.com/ − | publisher =The Guardian − | accessdate =22 December 2014 − }}

- ^ a b Winterman, Denise. "Upwardly gothic". BBC News Magazine.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Morgan, Fiona (16 December 1998). "The devil in your family room". Salon. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b ReligiousTolerance.org's article on "Goth"

- ^ "Goth subculture may protect vulnerable children". New Scientist. 14 April 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ^ "Vulnerable Goth Teens: The Role of Schools in This Psychosocial High-Risk Culture - Rutledge - 2008 - Journal of School Health - Wiley Online Library". .interscience.wiley.com. 6 August 2008. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ "Peer Group Self-Identification as a Predictor of Relational and Physical Aggression Among High School Students - Pokhrel - 2010 - Journal of School Health - Wiley Online Library". .interscience.wiley.com. 17 July 2009. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ a b Montenegro, Marcia. "The World According to Goth". christiananswersforthenewage.org. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Cullen, Dave (23 September 1999). "Inside the Columbine High investigation Everything you know about the Littleton killings is wrong. But the truth may be scarier than the myths". salon.com. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b September 14, 2006. Shooting by Canadian trench coat killer affects industrial / goth scene Side-line.com. Retrieved on March 13, 2007.

- ^ CTV News (20 March 2007). "Details of Kimveer Gill's apology note revealed".

- ^ Kimveer Gill's VampireFreaks.com profile.

- ^ Singh, Raman NRI Kimveer Gill, Montreal native gunman called himself 'angel of death', kills one and injuring 20. NRI Retrieved on March 22, 2007.

- ^ Mick Mercer Mick Mercer talks about Kimveer Gill mickmercer.livejournal.com

- ^ "Shooter is described as 'Goth kid'", Star-Telegram (subscription required)

- ^ NBC, MSNBC and news services Teen who killed 9 claimed Nazi leanings MSNBC

- ^ CNN.com. 22 October 2005. Vitale slaying suspect charged with murder. Retrieved on March 13, 2007.

- ^ Reynolds, Richard (28 April 2006). "Accused killer, 12, linked to goth site". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Johnsrude, Larry (26 April 2006). "Goths say Medicine Hat killings give them bad name". canada.com. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (1 May 1999). "Terror in Littleton: The Shunned; For Those Who Dress Differently, an Increase in Being Viewed as Abnormal". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Goths and Violent Crime Gothic Angst Webzine. 8 Sep 2007

- ^ Goth Help Us, San Diego Gothic Angst Webzine. 1 May 2007

- ^ James Howard (1 September 2007). "Vindication". community.livejournal.com. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ "Goth couple badly hurt in attack". BBC News-UK. 11 August 2007. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Byrne, Paul (29 April 2008). "Life jail trms for teenage thugs who killed goth girl". dailyrecord.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Pilling, Kim (29 April 2008). "Two teenagers sentenced to life over murder of Goth". Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Henfield, Sally (29 April 2008). "Sophie's family and friends vow to carry on campaign". lancashiretelegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Smyth, Catherine (4 April 2008). "Call for hate crimes law change". manchestereveningnews.co.uk. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Rothwelltoday.co.uk

- ^ Alterophobia.blogspot.com

- ^ Rothwelltoday.co.uk

- ^ Telegraph.co.uk

- ^ Foxnews.com

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Manchester goths get police protection". 3 News NZ. 5 April 2013.

- ^ "Prevalence of deliberate self harm and attempted suicide within contemporary Goth youth subculture: longitudinal cohort study". BMJ. 13 April 2006. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- ^ Polly Curtis and John Carvel. "Teen goths more prone to suicide, study shows." The Guardian, Friday 14 April 2006

- ^ Robert Young, Helen Sweeting, Patrick West (4 May 2006). "Prevalence of deliberate self harm and attempted suicide within contemporary Goth youth subculture: longitudinal cohort study". British Medical Journal. 332 (7549): 1058–1061. doi:10.1136/bmj.38790.495544.7C. PMC 1458563. PMID 16613936. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Gaia Vince (14 April 2006). "Goth subculture may protect vulnerable children". New Scientist. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ a b c "Goths 'more likely to self-harm'". BBC. 13 April 2006. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- ^ Sources:

This most likely meant that, according to the survey, there was more of a stereotype towards goths that they did practice self-harming. Some would argue that it is a very unfair stereotype to place upon goths, as the vast majority of the goth subculture is against even the thought of practicing self-harm and is strongly against it.

- Letter to the editor Mark Taubert, senior house officer in palliative medicine Holme Tower Marie Curie Hospital, Jothy Kandasamy specialist registrar in neurosurgery Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery (20 May 2006). "Letters. Self harm in Goth youth subculture: Conclusion relates only to small sample". BMJ. 1 (332(7551)): 1216. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1216. PMC 1463972. PMID 16710018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Letter to the editor Phillipov, M (20 May 2006). "Letter. Self harm in Goth youth subculture: Study merely reinforces popular stereotypes". BMJ. 332 (7551): 1215–1216. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1215-b. PMC 1463947. PMID 16710012.

- Author's reply Young, R; Sweeting, H; West, P (3 June 2006). "Letter. Self harm in Goth youth subculture: authors' reply". BMJ. 332 (7553): 1335. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7553.1335-a. PMC 1473089. PMID 16740576.

- Letter to the editor Mark Taubert, senior house officer in palliative medicine Holme Tower Marie Curie Hospital, Jothy Kandasamy specialist registrar in neurosurgery Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery (20 May 2006). "Letters. Self harm in Goth youth subculture: Conclusion relates only to small sample". BMJ. 1 (332(7551)): 1216. doi:10.1136/bmj.332.7551.1216. PMC 1463972. PMID 16710018.

Sources

- Goodlad, Lauren M. E.; Bibby, Michael (2007), "Introduction", Goth: Undead Subculture, Duke University Press, ISBN 978-0822389705

References

- Andrew C. Zinn: The Truth Behind The Eyes (IUniverse, US, 2005; ISBN 0-595-37103-5)—Dark Poetry

- Baddeley, Gavin: Goth Chic: A Connoisseur's Guide to Dark Culture (Plexus, US, August 2002, ISBN 0-85965-308 0)

- Catalyst, Clint: Cottonmouth Kisses. (Manic D Press, 2000 ISBN 978-0-916397-65-4 )- A first-person account of an individual's life within the Goth Subculture (book has Library of Congress listing under "Goth Subculture").

- Davenport-Hines, Richard: Gothic: Four Hundred Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin. 1999: North Port Press. ISBN 0-86547-590-3 (trade paperback)—A chronological/aesthetic history of Goth covering the spectrum from Gothic architecture to The Cure.

- Digitalis, Raven: Goth Craft: The Magickal Side of Dark Culture (2007: Llewellyn Worldwide)—includes a lengthy explanation of Gothic history, music, fashion, and proposes a link between mystic/magical spirituality and dark subcultures.

- Embracing the Darkness; Understanding Dark Subcultures by Corvis Nocturnum (Dark Moon Press 2005. ISBN 978-0-9766984-0-1)

- Fuentes Rodríguez, César: Mundo Gótico. (Quarentena Ediciones, 2007, ISBN 84-933891-6-1)—In Spanish. Covering Literature, Music, Cinema, BDSM, Fashion and Subculture topics

- Furek, Maxim W.: The Death Proclamation of Generation X: A Self-Fulfilling Prophesy of Goth, Grunge and Heroin". (i-Universe, US 2008; ISBN 978-0-595-46319-0)

- Hodkinson, Paul: Goth: Identity, Style and Subculture (Dress, Body, Culture Series) 2002: Berg. ISBN 1-85973-600-9 (hardcover); ISBN 1-85973-605-X (softcover)

- Kilpatrick, Nancy: The Goth Bible: A Compendium for the Darkly Inclined. 2004: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 0-312-30696-2

- Mercer, Mick: 21st Century Goth (Reynolds & Hearn, 2002; ISBN 1-903111-28-5)—an exploration of the modern state of the Goth subculture worldwide.

- Mercer, Mick: Hex Files: The Goth Bible. (9 Overlook Press, 1 Amer ed edition, 1997 ISBN 0-87951-783-2)—an international survey of the Goth scene.

- Reynolds, Simon (2005). "Dark Things: Goth and the Return of Rock". Rip it up and Start Again: Postpunk 1978–84. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-21569-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scharf, Natasha: Worldwide Gothic. (Independent Music Press, 2011 ISBN 978-1-906191-19-1 ) - A global view of the Goth scene from its birth in the late 1970s to the present day.

- Vas, Abdul: "For Those About to Power". (T.F. Editores, 2012; ISBN 9788415253525) Hardcover 208 pages

- Venters, Jillian: Gothic Charm School: An Essential Guide for Goths and Those Who Love Them.(Harper Paperbacks, 2009 ISBN 0-06-166916-4) - An etiquette guide to "gently persuade others in her chosen subculture that being a polite Goth is much, much more subversive than just wearing T-shirts with "edgy" sayings on them."

- Voltaire: What is Goth? (WeiserBooks, US, 2004; ISBN 1-57863-322-2)—an illustrated view of the Goth subculture

Further reading

- Brill, D. (2008). Goth Culture: Gender, Sexuality and Style. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

- Goodlad, Lauren M. E.; Michael Bibby, eds. (2007). Goth: Undead Subculture. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3921-8.

- Hodkinson, Paul (2005). "Communicating Goth: On-line Media". In Ken Gelder (ed.). The Subcultures Reader (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. pp. 567–574. ISBN 0-415-34416-6.