History of the Catholic Church in the United States

Catholicism arrived in the colonial era, but most of the Spanish and French influences had faded by 1800. The Catholic Church grew through immigration, especially from Europe (Germany and Ireland at first, and in 1890-1914 from Italy, Poland and Eastern Europe. In the nineteenth century the Church set up an elaborate infrastructure, based on diocese run by bishops appointed by the pope. Each diocese set up a network of parishes, schools, colleges, hospitals, orphanages and other charitable institutions. Many priests arrived from France and Ireland, but by 1900 Catholic seminaries were producing a sufficient supply of priests. Many young women became nuns, typically working as teachers and nurses. The Catholic population was primarily working-class until after World War II when it increasingly moved into white-collar status and left the inner city for the suburbs. After 1960, the number of priests and nuns fell rapidly and new vocations were few. The Catholic population was sustained by a large influx from Mexico and other Latin American nations. As the Catholic colleges and universities matured, questions were raised about their adherence to orthodox Catholic theology. After 1980, the Catholic bishops became involved in politics, especially on issues relating to abortion and sexuality.

In 2008 24% of Americans identified themselves as Roman Catholic.

Colonial era

In general

The history of Roman Catholicism in the United States – prior to 1776 – often focuses on the 13 English-speaking colonies along the Atlantic seaboard, as it was they who declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, to form the United States of America. However, this history – of Roman Catholicism in the United States – also includes the French and Spanish colonies, because they later became the greater part of continental United States.

In 1634, Maryland recorded a little less than 3,000 Catholics out of a population of 34,000 (around 9% of the population). In 1757, Pennsylvania recorded fewer than 1,400 Catholics out of a population of about 200,000. In 1785, when the newly founded United States (formerly the Thirteen Colonies) contained nearly four million people, there were fewer than 25,000 Catholics (about 0.6% of the population).

Spanish Missions

Catholicism first came to the territories now forming the United States before the Protestant Reformation with the Spanish explorers and settlers in present-day Florida (1513), South Carolina (1566), Georgia (1568–1684), and the southwest. The first Catholic Mass held in the current United States was in 1526 by Dominican friars Fr. Antonio de Montesinos and Fr. Anthony de Cervantes, who ministered to the San Miguel de Gualdape colonists for the 3 months the colony existed.[2]

The influence of the Alta California missions (1769 and onwards) forms a lasting memorial to part of this heritage. Until the 19th century, the Franciscans and other religious orders had to operate their missions under the Spanish and Portuguese governments and military.[3] Junípero Serra founded a series of missions in California which became important economic, political, and religious institutions.[4] These missions brought grain, cattle and a new way of living to the Indian tribes of California. Overland routes were established from New Mexico that resulted in the colonization and founding of San Diego at Mission San Diego de Alcala (1760), Mission San Carlos Borromeo de Carmelo at Carmel-by-the-Sea, California in (1770), Mission San Francisco de Asis (Mission Dolores) at San Francisco (1776), Mission San Luis Obispo at San Luis Obispo (1772), Mission Santa Clara de Asis at Santa Clara (1777), Mission Senora Reina de los Angeles Asistencia in Los Angeles (1784), Mission Santa Barbara at Santa Barbara (1786), Mission San Juan Bautista in San Juan Bautista (1797), among numerous others.

French territories

In the French territories, Catholicism was ushered in with the establishment of missions such as Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan (1668), St. Igance on the Straits of Mackinac, Michigan (1671) and Holy Family at Cahokia, Illinois (1699) and then colonies and forts in Detroit (1701), St. Louis, Mobile (1702), Kaskaskia, Il (1703), Biloxi, Baton Rouge, and New Orleans(1718). In the late 17th century, French expeditions, which included sovereign, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. Small settlements were founded along the banks of the Mississippi and its major tributaries, from Louisiana to as far north as the region called the Illinois Country.[5]

The French possessions were under the authority of the diocese of Quebec, under an archbishop, chosen and funded by the king. The religious fervor of the population was very weak; Catholics ignored the tithe, a 10% tax to support the clergy. By 1720, the Ursulines were operating a hospital in New Orleans. The Church did send Companions of the Seminary of Quebec and Jesuits as missionaries, to convert Native Americans. These missionaries introduced the Natives to Catholicism in stages.

English colonies

Catholicism was introduced to the English colonies with the founding of the Province of Maryland.[6] Maryland was one of the few regions among the English colonies in North America that was predominantly Catholic. However, the 1646 defeat of the Royalists in the English Civil War led to stringent laws against Catholic education and the extradition of known Jesuits from the colony, including Andrew White, and the destruction of their school at Calverton Manor.[7] During the greater part of the Maryland colonial period, Jesuits continued to conduct Catholic schools clandestinely.

Maryland was a rare example of religious toleration in a fairly intolerant age, particularly amongst other English colonies which frequently exhibited a militant Protestantism. The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity. It has been considered a precursor to the First Amendment.

After Virginia established Anglicanism as mandatory in the colony, numerous Puritans migrated from Virginia to Maryland. The government gave them land for a settlement called Providence (now called Annapolis). In 1650, the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government and set up a new government that outlawed both Catholicism and Anglicanism. The Puritan revolt lasted until 1658, when the Calvert family regained control and re-enacted the Toleration Act.

Origins of anti-Catholicism

American Anti-Catholicism and Nativist Opposition to Catholic immigrants had their origins in the Reformation. Because the Reformation, from the Protestant perspective, was based on an effort by Protestants to correct what they perceived to be errors and excesses of the Catholic Church, it formed strong positions against the Catholic interpretation of the Bible, the Catholic hierarchy and the Papacy. "To be English was to be anti-Catholic," writes Robert Curran.[8] These positions were brought to the eastern seaboard of the New World by British colonists, predominantly Protestant, who opposed not only the Roman Catholic Church in Europe and in French and Spanish-speaking colonies of the New World, but also the policies of the Church of England in their own homeland, which they believed perpetuated Catholic doctrine and practices, and, for that reason, deemed it to be insufficiently Reformed.

Because many of the British colonists were Dissenters, such as the Puritans and Congregationalists, and thus were fleeing religious persecution by the Church of England, much of early American religious culture exhibited the anti-Catholic bias of these Protestant denominations. Monsignor John Tracy Ellis wrote that a "universal anti-Catholic bias was brought to Jamestown in 1607 and vigorously cultivated in all the thirteen colonies from Massachusetts to Georgia."[9] Colonial charters and laws contained specific proscriptions against Roman Catholics. Monsignor Ellis noted that a common hatred of Catholics in general could unite Anglican clerics and Puritan ministers despite their differences and conflicts.

Before the Revolution, most of 13 colonies also had established churches, either Congregational or Anglican. This only meant that local tax money was spent for the local church, which sometimes (as in Virginia) handled poor relief and roads. Churches that were not established were tolerated and governed themselves; they functioned with private funds.[10]

American Revolution

By the time of the American Revolution, 35,000 Catholics formed 1.2% of the 2.5 million white population of the thirteen seaboard colonies.[11] One of the signatories of the Declaration of Independence, Charles Carroll (1737-1832), owner of sixty thousand acres of land, was a Catholic and was one of the richest men in the colonies. Catholicism was integral to his career. He was dedicated to American Republicanism, but feared extreme democracy.[12][13]

Before independence in 1776 the Catholics in Britain's thirteen colonies in America were under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the bishop of the Apostolic Vicariate of the London District, in England.

A petition was sent by the Maryland clergy to the Holy See, on November 6, 1783, for permission for the missionaries in the United States to nominate a superior who would have some of the powers of a bishop. In response to that, Father John Carroll – having been selected by his brother priests – was confirmed by Pope Pius VI, on June 6, 1784, as Superior of the Missions in the United States, with power to give the sacrament of confirmation. This act established a hierarchy in the United States.

The Holy See then established the Apostolic Prefecture of the United States on November 26, 1784. Because Maryland was one of the few regions of the new country that had a large Catholic population, the apostolic prefecture was elevated to become the Diocese of Baltimore[14] – the first diocese in the United States – on November 6, 1789.

Thus, Father John Carroll, a former Jesuit, became the first American-born head of the Catholic Church in America, although the papal suppression of the Jesuit order was still in effect. Carroll orchestrated the founding and early development of Georgetown University which began instruction on November 22, 1791.[15]

In 1788, after the Revolution, John Jay urged the New York Legislature to require office-holders to renounce foreign authorities "in all matters ecclesiastical as well as civil."[16] In one state, North Carolina, the Protestant test oath would not be changed until 1868.

19th century

The Catholic population of the United States, which had been 35,000 in 1790, increased to 195,000 in 1820 and then ballooned to about 1.6 million in 1850, by which time, Catholics had become the country’s largest denomination. Between 1860 and 1890 the population of Roman Catholics in the United States tripled primarily through immigration. By the end of the century, there were 12 million Catholics in the United States.

Immigration

During the 19th century, a wave of immigrants from Ireland, Germany, Italy, Eastern Europe and elsewhere swelled the number of Roman Catholics. Substantial numbers of Catholics also came from French Canada during the mid-19th century and settled in New England. This influx would eventually bring increased political power for the Roman Catholic Church and a greater cultural presence, led at the same time to a growing fear of the Catholic "menace."

Archdiocese of Baltimore

Because Maryland was one of the few regions of the colonial United States that was predominantly Catholic, the first diocese in the United States was established in Baltimore. Thus, the Diocese of Baltimore achieved a pre-eminence over all future dioceses in the U.S. It was established as a diocese on November 6, 1789, and was elevated to the status of an archdiocese on April 8, 1808.

In 1858, the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide), with the approval of Pius IX, conferred "Prerogative of Place" on the Archdiocese of Baltimore. This decree gave the archbishop of Baltimore precedence over all the other archbishops of the United States (but not cardinals) in councils, gatherings, and meetings of whatever kind of the hierarchy (in conciliis, coetibus et comitiis quibuscumque) regardless of the seniority of other archbishops in promotion or ordination.[17]

Dominance of Irish Americans

Beginning in the 1840s, Irish American Catholics comprised most of the bishops and controlled most of the Catholic colleges and seminaries in the United States. In 1875, John McCloskey of New York became the first American cardinal.

Parochial schools

The development of the American Catholic parochial school system can be divided into three phases. During the first (1750–1870), parochial schools appeared as ad hoc efforts by parishes, and most Catholic children attended public schools. During the second period (1870–1910), the Catholic hierarchy made a basic commitment to a separate Catholic school system. These parochial schools, like the big-city parishes around them, tended to be ethnically homogeneous; a German child would not be sent to an Irish school, nor vice versa, nor a Lithuanian pupil to either. Instruction in the language of the old country was common. In the third period (1910–1945), Catholic education was modernized and modeled after the public school systems, and ethnicity was deemphasized in many areas. In cities with large Catholic populations (such as Chicago and Boston) there was a flow of teachers, administrators, and students from one system to the other.[18]

Catholic schools began as a program to shelter Catholic students from Protestant teachers (and schoolmates) in the new system of public schools that emerged in the 1840s.

In 1875, Republican President Ulysses S. Grant called for a Constitutional amendment that would prohibit the use of public funds for "sectarian" schools. Grant feared a future with "patriotism and intelligence on one side and superstition, ambition and greed on the other" which he identified with the Catholic Church. Grant called for public schools that would be "unmixed with atheistic, pagan or sectarian teaching." No such federal constitutional amendment ever passed, but most states did pass so-called "Blaine Amendments" that prohibited the use of public funds to fund parochial schools and are still in effect today.

Slavery debate

Two slaveholding states, Maryland and Louisiana, had large contingents of Catholic residents. Archbishop of Baltimore, John Carroll, had two black servants – one free and one a slave. The Society of Jesus owned a large number of slaves who worked on the community's farms. Realizing that their properties were more profitable if rented out to tenant farmers rather that worked by slaves, the Jesuits began selling off their slaves in 1837.

In 1839, Pope Gregory XVI issued a Bull, titled In Supremo. Its main focus was against slave trading, but it also clearly condemned racial slavery:

- We, by apostolic authority, warn and strongly exhort in the Lord faithful Christians of every condition that no one in the future dare bother unjustly, despoil of their possessions, or reduce to slavery Indians, Blacks or other such peoples.

However, the American church continued in deeds, if not in public discourse, to support slaveholding interests. Some American bishops misinterpreted In Supremo as condemning only the slave trade and not slavery itself. Bishop John England of Charleston actually wrote several letters to the Secretary of State under President Van Buren explaining that the Pope, in In Supremo, did not condemn slavery but only the slave trade.[19]

One outspoken critic of slavery was Archbishop John Baptist Purcell of Cincinnati, Ohio. In an 1863 Catholic Telegraph editorial Purcell wrote:

- "When the slave power predominates, religion is nominal. There is no life in it. It is the hard-working laboring man who builds the church, the school house, the orphan asylum, not the slaveholder, as a general rule. Religion flourishes in a slave state only in proportion to its intimacy with a free state, or as it is adjacent to it."

During the war, American bishops continued to allow slave-owners to take communion. During the Civil War, some like former priest Charles Chiniquy claimed that Pope Pius IX was behind the Confederate cause, that the American Civil War was a plot against the United States of America by the Vatican. The Catholic Church, having by its very nature a universal view, urged a unity of spirit. Catholics in the North rallied to enlist. Nearly 150,000 Irish Catholics fought for the Union, many in the famed Irish Brigade, as well as approximately 40,000 German-Catholics, and 5,000 Polish-Catholic immigrants. Catholics became prominent in the officer corps, including over fifty generals and a half-dozen admirals. Along with the soldiers that fought in the ranks were hundreds of priests who ministered to the troops and Catholic religious sisters who assisted as nurses and sanitary workers.

After the war, in October 1866, President Andrew Johnson and Washington’s mayor attended the closing session of a plenary council in Baltimore, giving tribute to the role Catholics played in the war and to the growing Catholic presence in America.

African-American Catholics

Because the South was over 90% Protestant, most African-Americans who adopted Christianity became Protestant; some became Catholics in the Gulf South, particularly Louisiana. The French Code Noir which regulated the role of slaves in colonial society guaranteed the rights of slaves to baptism, religious education, communion, and marriage. The parish church in New Orleans was unsegregated. Predominantly black religious orders emerged, including the Sisters of the Holy Family in 1842. The Church of Saint Augustine in the Tremé district is among a number of historically black parishes. Xavier University, America's only historically-black Catholic institute of higher learning, was founded in New Orleans by Saint Katherine Drexel in 1915.[20]

Maryland Catholics owned slaves starting in the colonial era; in 1785, about 3000 of the 16,000 Catholics were black. Some owners and slaves moved west to Kentucky.[21] In 1835, Bishop John England, established free schools for black children in Charleston, South Carolina. White mobs forced it to close. African-American Catholics operated largely as segregated enclaves. They also founded separate religious institutes for black nuns and priests since diocesan seminaries would not accept them. For example, they formed two separate communities of black nuns: the Oblate Sisters of Providence in 1829 and the Holy Family Sisters in 1842.

James Augustine Healy was the first African American to become a priest. , became the second bishop of the Diocese of Portland, Maine in 1875. His brother, Patrick Francis Healy, joined the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) in Liege, France in 1864 and became the president of Georgetown University ten years later.[22]

In 1866, Archbishop Martin J. Spalding of Baltimore convened the Second Plenary Council of Baltimore, partially in response to the growing need for religious care for former slaves. Attending bishops remained divided over the issue of separate parishes for African-American Catholics.

In 1889, Daniel Rudd, a former slave and Ohio journalist, organized the National Black Catholic Congress, the first national organization for African-American Catholic lay men. The Congress met in Washington, D.C. and discussed issues such as education, job training, and "the need for family virtues."[23]

In 2001, Bishop Wilton Gregory was appointed president of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, the first African American ever to head an episcopal conference.

Plenary Councils of Baltimore

Catholic bishops met in three of Plenary Councils in Baltimore in 1852, 1866 and 1884, establishing national policies for all diocese.[24] One result of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884 was the development of the Baltimore Catechism which became the standard text for Catholic education in the United States and remained so until the 1960s when Catholic churches and schools began moving away from catechism-based education.[25]

Another result of this council was the establishment of The Catholic University of America, the national Catholic university in the United States.

Labor union movement

Irish Catholics took a prominent role in shaping America's labor movement. Most Catholics were unskilled or semi-skilled urban workers, and the Irish used their strong sense of solidarity to form a base in unions and in local Democratic politics. Nativism, and anti-Catholicism were reactions that found a home in the Republican Party. By 1910 a third of the leadership of the labor movement was Irish Catholic, and German Catholics were actively involved as well.[26]

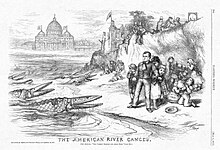

Anti-Catholicism

Some anti-immigrant and Nativism movements, like the Know Nothings have also been anti-Catholic. Anti-Catholicism was led by Protestant ministers who labeled Catholics as un-American "Papists", incapable of free thought without the approval of the Pope, and thus incapable of full republican citizenship. This attitude faded after Catholics proved their citizenship by service in the American Civil War, but occasionally emerged in political contests, especially the presidential elections of 1928 and 1960, when Catholics were nominated by the Democratic Party. Democrats won 65–80% of the Catholic vote in most elections down to 1964, but since then have split about 50-50.

Americanist controversy

Americanism was considered a heresy by the Vatican that consisted of too much theological liberalism and too ready acceptance of the American policy of separation of church and state. Rome feared that such a heresy was held by Irish Catholic leaders in the United States, such as Isaac Hecker, and bishops John Keane, John Ireland, and John Lancaster Spalding, as well as the magazines Catholic World and Ave Marie. Allegations came from German American bishops angry with growing Irish domination of the Church.

The Vatican grew alarmed in the 1890s, and the Pope issued an encyclical denouncing Americanism in theory. In "Longinqua oceani" (1895; “Wide Expanse of the Ocean”), Pope Leo XIII warned the American hierarchy not to export their unique system of separation of church and state. In 1898 he lamented an America where church and state are "dissevered and divorced," and wrote of his preference for a closer relationship between the Catholic Church and the State. Finally, in his pastoral letter Testem benevolentiae (1899; “Witness to Our Benevolence”) to Cardinal James Gibbons, Pope Leo XIII condemned other forms of Americanism. In response, Gibbons denied that American Catholics held any of the condemned views.

Leo's pronouncements effectively ended the Americanist movement and curtailed the activities of American progressive Catholics. The Irish Catholics increasingly demonstrated their total loyalty to the Pope, and traces of liberal thought in the Catholic colleges were suppressed. At bottom it was a cultural conflict, as the conservative Europeans were alarmed mostly by the heavy attacks on the Catholic church in Germany, France and other countries, and did not appreciate the active individualism self-confidence and optimism of the American church. In reality Irish Catholic laymen were deeply involved in American politics, but the bishops and priests kept their distance.[27][28]

20th century

By the beginning of the 20th century, approximately one-sixth of the population of the United States was Roman Catholic. By the end of the 20th century, Catholics constituted 24% of the population.

National Catholic War Council

It was John J. Burke, editor of the Catholic World, who first recognized the urgency of the moment. Burke had long argued for a national outlook and sense of unity among the country’s Catholics. The war provided the impetus to initiate these efforts. The Catholic hierarchy was eager to show its enthusiastic support for the war effort. In order to better address challenges posed by World War I, the American Catholic hierarchy in 1917 chose to meet collectively for the first time since 1884.

In August 1917, on the campus of The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., Burke, with the backing of Cardinal Gibbons and other bishops, convened a meeting to discuss organizing a national agency to coordinate the war effort of the American Catholic community. One hundred and fifteen delegates from sixty-eight dioceses, together with members from the Catholic press and representatives from twenty-seven national Catholic organizations attended this first meeting.

The result of the meeting was the formation of the National Catholic War Council, "to study, coordinate, unify and put in operation all Catholic activities incidental to the war." An executive committee, chaired by Cardinal George Mundelein of Chicago, was formed in December 1917, to oversee the work of the Council. The mandate of the newly formed organization included the promotion of Catholic participation in the war, through chaplains, literature, and care for the morale of the troops, as well as (for the first time) lobbying for Catholic interests in the nation’s capital.

NCWC

In 1919, the National Catholic Welfare Council, composed of US Catholic bishops, founded NCWC at the urging of heads of Catholic women's organizations desiring a federation for concerted action and national representation. The formal federation evolved from the coordinated efforts of Catholic women's organizations in World War I in assisting servicemen and their families and doing relief work.

Bureau of Immigration

In 1920, the National Catholic Welfare Council established a Bureau of Immigration to assist immigrants in getting established in the United States. The Bureau launched a port assistance program that met incoming ships, helped immigrants through the immigration process and provided loans to them. The bishops, priests, and laymen and women of the National Catholic Welfare Conference (NCWC) became some of the most outspoken critics of US immigration.[29]

Bishops' Program of Social Reconstruction

Following the war many hoped that a new commitment to social reform would characterize the ensuing peace. The Council saw an opportunity to use its national voice to shape reform and in April 1918 created a Committee for Reconstruction. John A. Ryan wrote the Bishops' Program of Social Reconstruction.

On February 12, 1919, the National Catholic War Council issued the "Bishops' Program of Social Reconstruction," through a carefully planned public relations campaign. The plan offered a guide for overhauling America's politics, society, and economy based on Pope Leo XIII's Rerum Novarum and a variety of American influences.

The Program received a mixed reception both within the Church and outside it. The National Catholic War Council was a voluntary organization with no canonical status. Its ability to speak authoritatively was thus questioned. Many bishops threw their support behind the Program, but some, like Bishop William Turner of Buffalo, and more notably, William Henry O'Connell of Boston, opposed it. O'Connell believed some aspects of the plan smacked too much of socialism. Response outside the Church was also divided: labor organizations backing it, for example, and business groups criticizing it.

Compulsory Education Act

After World War I, some states concerned about the influence of immigrants and "foreign" values looked to public schools for help. The states drafted laws designed to use schools to promote a common American culture.

In 1922, the Masonic Grand Lodge of Oregon sponsored a bill to require all school-age children to attend public school systems. With support of the Knights of the KKK and Democratic Governor Walter M. Pierce, the Compulsory Education Act was passed by a vote of 115,506 to 103,685. Its primary purpose was to shut down Catholic schools in Oregon, but it also affected other private and military schools. The constitutionality of the law was challenged in court and ultimately struck down by the Supreme Court in Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) before it went into effect.[30]

The law caused outraged Catholics to organize locally and nationally for the right to send their children to Catholic schools. In Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925), the United States Supreme Court declared the Oregon's Compulsory Education Act unconstitutional in a ruling that has been called "the Magna Carta of the parochial school system."

1928 Presidential election

In 1928, Al Smith became the first Roman Catholic to gain a major party's nomination for president, and his religion became an issue during the campaign. Many Protestants feared that Smith would take orders from church leaders in Rome in making decisions affecting the country.

Catholic Worker Movement

The Catholic Worker movement began as a means to combine Dorothy Day's history in American social activism, anarchism, and pacifism with the tenets of Catholicism (including a strong current of distributism), five years after her 1927 conversion.[31] The group started with the Catholic Worker newspaper, created to promote Catholic social teaching and stake out a neutral, pacifist position in the war-torn 1930s. This grew into a "house of hospitality" in the slums of New York City and then a series of farms for people to live together communally. The movement quickly spread to other cities in the United States, and to Canada and the United Kingdom; more than 30 independent but affiliated CW communities had been founded by 1941. Well over 100 communities exist today, including several in Australia, the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, The Netherlands, the Republic of Ireland, Mexico, New Zealand, and Sweden.[32]

Catholic Conference on Industrial Problems

The Catholic Conference on Industrial Problems (1923–1937) was conceived by Fr. Raymond McGowan as a way of bringing together Catholic leaders in the fields of theology, labor, and business, with a view to promoting awareness and discussion of Catholic social teaching. Its first meeting was held in Milwaukee. While it was the venue for important discussions during its existence, its demise was due in part to lack of participation by business executives who perceived the dominant tone of the group as anti-business.

1960s

The 1960s marked a profound transformation of the Catholic Church in the United States. [33]

Religion briefly became a divisive issue during the presidential campaign of 1960. Senator John F. Kennedy won the Democratic nomination. His base was among urban Catholics and polls showed they rallied to his support while most Protestants favored his opponent Richard Nixon. The old fear was raised by some Protestants that President Kennedy would take orders from the pope.[34] Kennedy famously told the Greater Houston Ministerial Association on September 12, 1960, "I am not the Catholic candidate for President. I am the Democratic Party's candidate for President who also happens to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters – and the Church does not speak for me."[35] He promised to respect the separation of church and state and not to allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him. Kennedy also raised the question of whether one-quarter of Americans were relegated to second-class citizenship just because they were Roman Catholic. The New York Times, summarizing the research of pollsters spoke of a “narrow consensus” among the experts that Kennedy had won more than he lost as a result of his Catholicism,.[36] After that religion of Catholic candidates was rarely mentioned. In 2004, Catholics split about evenly between the Protestant (George W. Bush) and the Catholic (John F. Kerry) candidates.[37]

1970s

The number of priests, brothers and nuns dropped sharply in the 1960s and 1970s as many left and few replacements arrived. Catholic parochial schools had been built primarily in the cities, with few in the suburbs or small towns. Many continue to operate, but with the loss of so many low-cost nuns, they have to hire much more expensive lay teachers. Most inner-city parishes saw white flight to the suburbs, so by the 1990s the remaining schools often had a largely minority student body, which attracts upwardly mobile students away from the low-quality, high-violence free public schools.

Roe v. Wade

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court of the United States announced its decision in the Roe v. Wade case, finding that a constitutional right to privacy prohibited interference with a woman's obtaining an abortion. The Catholic Church was one of the few institutional voices opposing the decision at the time. Though a majority of Catholics have agreed with the hierarchy in their insistence on legal protection of the unborn, some—including prominent politicians—have not, leading to perennial controversies concerning the responsibilities of Catholics in American public life. The bishops took the initiative and were able to form a political coalition with Fundamentalist Protestants in opposition to abortion laws.

1980s

Sanctuary of refugees from Central American civil wars was a movement in the 1980s. It was part of a broader anti-war movement positioned against U.S. foreign policy in Central America. By 1987, 440 sites in the United States had been declared "sanctuary congregations" or "sanctuary cities" open to migrants from the civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala. These sites included university campuses.

The movement originated along the U.S. border with Mexico in Arizona but was also strong in Chicago, Philadelphia, and California. In 1981, Rev. John Fife and Jim Corbett, among others, began bringing Central American refugees into the United States. It was their intent to offer sanctuary, or faith-based protection, from the political violence that was taking place in El Salvador and Guatemala.[38] The Department of Justice indicted several activists in south Texas for assisting refugees. Later 16 activists in Arizona were indicted, including Fife and Corbett in 1985; 11 were brought to trial and 8 were convicted of alien smuggling and other charges. The defendants claimed their actions were justifiable to save lives of people who would be killed and had no other way to escape.

This movement has been succeeded in the 2000s by the movement of churches and other houses of worship, to shelter immigrants in danger of deportation. The New Sanctuary Movement is a network of houses of worship that facilitates this effort.[39]

21st century

Immigration

Modern Roman Catholic immigrants come to the United States from the Philippines, Poland, and Latin America, especially from Mexico. This multiculturalism and diversity has greatly impacted the flavor of Catholicism in the United States. For example, many dioceses serve in both the English language and the Spanish language. Also, when many parishes were set up in the United States, separate churches were built for parishioners from Ireland, Germany, Italy, etc. In Iowa, the development of the Archdiocese of Dubuque, the work of Bishop Loras and the building of St. Raphael's Cathedral illustrate this point.

A 2008 survey by the Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, a project of the Pew Research Center, found that 23.9% of 300 million Americans (i.e., 72 million) identified themselves as Roman Catholic and that 29% of these were Hispanic/Latino, while nearly half of all Catholics under 40 years of age were Hispanic/Latino. The survey also found that white American Catholics were seven times more likely to have graduated high school than Hispanic/Latino Catholics, and that over twice as many Hispanic/Latino Catholics earned under $30,000 per year as their white counterparts.[40] According to the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, 15% of new priests are Hispanic/Latino and there are 28 active and 12 inactive Hispanic/Latino bishops, 9% of the total.[41] According to Luis Lugo, the director of the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, nearly a quarter of all Catholics in the United States are foreign born. He notes: "To know what the country will be like in three decades, look at the Catholic church."[42]

Sex abuse scandal

In the later 20th century "[...] the Catholic Church in the United States became the subject of controversy due to allegations of clerical child abuse of children and adolescents, of episcopal negligence in arresting these crimes, and of numerous civil suits that cost Catholic dioceses hundreds of millions of dollars in damages."[43] Although evidence of such abuse was uncovered in other countries, the vast majority of sex abuse cases occurred in the United States.[44]

Major lawsuits emerged in 2001 and subsequent years claiming some priests had sexually abused minors.[45] These allegations of priests sexually abusing children were widely reported in the news media. Some commentators, such as journalist Jon Dougherty, have argued that media coverage of the issue has been excessive, given that the same problems plague other institutions, such as the US public school system, with much greater frequency.[46][47][48]

Some priests resigned, others were defrocked and jailed,[49] and there were financial settlements with many victims.[45]

One estimate suggested that up to 3% of U.S. priests were involved.[50]

The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops commissioned a comprehensive study that found that four percent of all priests who served in the US from 1950 to 2002 faced some sort of sexual accusation.[51][52]

The Church was widely criticized when it emerged that some bishops had known about abuse allegations, and reassigned accused priests after first sending them to psychiatric counseling.[45][52][53][54] Some bishops and psychiatrists contended that the prevailing psychology of the times suggested that people could be cured of such behavior through counseling.[53][55] Pope John Paul II responded by declaring that "there is no place in the priesthood and religious life for those who would harm the young".[56]

The U.S. Church instituted reforms to prevent future abuse by requiring background checks for Church employees;[57] because the vast majority of victims were teenage boys, the worldwide Church also prohibited the ordination of men with "deep–seated homosexual tendencies."[55][58] It now requires dioceses faced with an allegation to alert the authorities, conduct an investigation and remove the accused from duty.[57][59]

In 2008, the Vatican affirmed that the scandal was an "exceptionally serious" problem, but estimated that it was "probably caused by "no more than 1 per cent" of the over 400,000 Catholic priests worldwide.[51]

Legislative stances

The Roman Catholic Church has tried to influence legislation to preserve Sunday as a day of worship,[citation needed] to outlaw abortion[citation needed] and euthanasia.[citation needed] It has also supported legislation to restrict or not to promote the use of contraceptives.[citation needed]

Catholics currently active in American politics are members of both major parties, and currently hold many important offices. The most prominent include Vice President Joe Biden, Chief Justice John Roberts, Speaker of the House John Boehner, and Governor of California Jerry Brown. Additionally, Democratic governor Bill Richardson and Republican former mayor Rudy Giuliani, both Catholics, sought the nomination for their respective parties in the 2008 presidential election. Chief Justice John Roberts as well as five associate justices, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Antonin Scalia, Anthony Kennedy, and Sonia Sotomayor are members of the Supreme Court, resulting in a Catholic majority on the court.

Human sexuality

Some criticize[who?] the Church's teaching on sexual and reproductive matters.[60] The Church requires members to eschew homosexual practices,[61] artificial contraception,[62] and sex out of wedlock, as well as non-procreative sexual practices, including masturbation. Procuring or assisting in an abortion can carry the penalty of excommunication, as a specific offense.[63]

Although some[who?] charge that the Roman Catholic Church rejects sex for purposes other than procreation, the official Catholic teaching regards sexuality as "naturally ordered to the good of spouses" as well as the generation of children.[64]

Some criticize[who?] the Church's teaching on fidelity, sexual abstinence and its opposition to promoting the use of condoms as a strategy to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS (or teen pregnancy or STD) as counterproductive.[citation needed] The Roman Catholic Church has been both praised and criticized for its staunch pro-life efforts in all societies. The Church's denial of the use of condoms has provoked criticism especially in countries where AIDS and HIV infections are at epidemic proportions. The Church maintains that countries like Kenya where behavioral changes like abstinence are endorsed instead of condom use, are experiencing greater progress towards controlling the disease than those countries just promoting condoms.[65]

Contraception

The Roman Catholic Church maintains its opposition to birth control. Some Roman Catholic Church members and non-members criticize this belief as contributing to overpopulation, and poverty.[66]

Pope Paul VI reaffirmed the Church's position in his 1968 encyclical Humanae Vitae (Human Life). In this encyclical, the Pope acknowledges the realities of modern life, scientific advances, as well as the questions and challenges these raise. Furthermore, he explains that the purpose of intercourse is both "unitive and procreative", that is to say it strengthens the relationship of the husband and wife as well as offering the chance of creating new life. As such, it is a natural and full expression of our humanity. He writes that contraception "contradicts the will of the Author of life [God]. Hence to use this divine gift [sexual intercourse] while depriving it, even if only partially, of its meaning and purpose, is equally repugnant to the nature of man and of woman, and is consequently in opposition to the plan of God and His holy will."[67]

The Church stands by its doctrines on sexual intercourse as defined by the Natural law: intercourse must at once be both the renewal of the consummation of marriage and open to procreation. If each of these postulates are not met, the act of intercourse is, according to Natural Law, an objectively grave sin. Therefore, since artificial contraception expressly prevents the creation of a new life (and, the Church would argue, removes the sovereignty of God over all of Creation), contraception is unacceptable. The Church sees abstinence as the only objective moral strategy for preventing the transmission of HIV.[68][69]

The Church has been criticized for its opposition to promoting the use of condoms as a strategy to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS, teen pregnancy, and STDs.

Homosexual behavior

The Roman Catholic Church teaches that all Catholics must practice chastity according to their states of life,[70] and Catholics with homosexual tendencies must practice chastity in the understanding that homosexual acts are "intrinsically disordered" and "contrary to the natural law."[71] The Vatican has reiterated the standing instruction against ordaining gay candidates for the priesthood.[72]

See also

- 19th century history of the Catholic Church in the United States

- 20th century history of the Catholic Church in the United States

- Catholic Church in French Louisiana

- Catholic Church in the United States

- Catholic schools in the United States

- Catholic social activism in the United States

- Catholicism and American politics

- Ecclesiastical property in the United States

- National Museum of Catholic Art and History

- Roman Catholicism in the United States

Notes

- ^ Engelhardt, Zephyrin,O.F.M. San Juan Capistrano Mission, p. 258 , Standard Printing Co., Los Angeles 1922.

- ^ Schroeder, Henry Joseph. "Antonio Montesino." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 10. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 26 Jun. 2014

- ^ Franzen, 362

- ^ Norman, The Roman Catholic Church an Illustrated History (2007), pp. 111–2

- ^ Richard Middleton, Colonial America (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 407.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Edward A.; Nevils, William Coleman (January 1936). "Miniatures of Georgetown, 1634 to 1934". The Journal of Higher Education. 7 (1). Ohio State University Press: 56–57. doi:10.2307/1974310. JSTOR 1974310. Retrieved July 31, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Nevils, William Coleman (1934). Miniatures of Georgetown: Tercentennial Causeries. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 1–25.

- ^ Robert Emmett Curran, Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574-1783 (2014) pp 201-2

- ^ Ellis 1956

- ^ Richard Middleton, Colonial American (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2003), 260–1.

- ^ Middleton, 225. Also see Michael Lee Lanning, The American Revolution 100 (Napierville:Ill.: Sourcebook,Inc.), 193.

- ^ Bradley J. Birzer, American Cicero: The Life of Charles Carroll (2010) excerpt

- ^ Kate Mason Rowland, The life of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, 1737-1832: with his correspondence and public papers (1898) vol 2 online

- ^ Archdiocese of Baltimore official website. Retrieved November 26, 2009.

- ^ "William Gaston and Georgetown". Bicentennial Exhibit. Georgetown University. November 11, 2000. Retrieved July 3, 2007.

- ^ Kaminski, John (March 2002). "Religion and the Founding Fathers". Annotation – the Newsletter of the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. 30:1. ISSN 0160-8460.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Baltimore – Our History". Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2009.

- ^ Lazerson (1977)

- ^ Panzer, Joel (1996). The Popes and Slavery. Alba House.

- ^ Ronald L. Sharps, "Black Catholics in the United States: A historical chronology." US Catholic Historian (1994): 119-141. in JSTOR

- ^ Albert J. Raboteau, Canaan land: A religious history of African Americans (Oxford University Press, 2001) p 50-51

- ^ *Mazzocchi, J. "Healy, James Augustine", American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000

- ^ David Spalding, "The Negro Catholic Congresses, 1889-1894." Catholic Historical Review (1969): 337-357. in JSTOR

- ^ W. Fanning, "Plenary Councils of Baltimore." Catholic Encyclopedia 2 (1907), online.

- ^ Francis P. Cassidy, "Catholic Education in the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore. I." Catholic Historical Review (1948): 257-305. in JSTOR

- ^ Timothy J. Meagher, The Columbia guide to Irish American history (2005) pp 113–14

- ^ James Hennessy, S.J., American Catholics: A history of the Roman Catholic community in the United States (1981) pp 194-203

- ^ Thomas T. McAvoy, "The Catholic Minority after the Americanist Controversy, 1899-1917: A Survey," Review of Politics, Jan 1959, Vol. 21 Issue 1, pp 53–82 in JSTOR

- ^ Rachel Buff, ed. (2008). Immigrant Rights in the Shadows of Citizenship. NYU Press.

- ^ Howard, J. Paul. "Cross-Border Reflections, Parents’ Right to Direct Their Childrens’ Education Under the U.S. and Canadian Constitutions", Education Canada, v41 n2 p36-37 Sum 2001.

- ^ ""Dorothy Day, Prophet of Pacifism for the Catholic Church"" from "Houston Catholic Worker" newspaper, October 1997

- ^ Directory of Catholic Worker Communities "List of Catholic Worker Communities". Retrieved November 30, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Mark S. Massa, The American Catholic Revolution: How the Sixties Changed the Church Forever (2010) online

- ^ Shaun Casey, The Making of a Catholic President: Kennedy vs. Nixon 1960 (2008)

- ^ Kennedy, John F. (June 18, 2002). "Address to the Greater Houston Ministerial Association". American Rhetoric. Retrieved September 17, 2007.

- ^ New York Times, November 20, 1960, Section 4, p. E5

- ^ Robert D. Putnam; David E. Campbell (2010). American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us. Simon and Schuster. p. 2.

- ^ See James P. Carroll, 2006: "Sanctuary", in House of War, pp. 397–404. ISBN 0-618-18780-4

- ^ Sanctuary Movement history on New Sanctuary Movement page

- ^ "Pew Forum: A Portrait of American Catholics on the Eve of Pope Benedict's Visit to the U.S." The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. March 27, 2008. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "USCCB – (Hispanic Affairs) – Demographics". U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ^ "Panel offers observations on the impact of immigration on faith in the US," Boston Globe September 13, 2009, 3.

- ^ Patrick W. Carey, Catholics in America. A History, Westport, Connecticut and London: Praeger, 2004, p. 141

- ^ 1,200 Priests Reported Accused of Abuse Article from AP Online

- ^ a b c Bruni, p. 336.

- ^ Dougherty, Jon (April 5, 2004). "Sex Abuse by Teachers Said Worse Than Catholic Church". Newsmax. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ Irvine, Martha; Tanner, Robert (October 21, 2007). "Sexual Misconduct Plagues US Schools". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ Shakeshaft, Charol (2004). "Educator Sexual Misconduct" (PDF). US Department of Education. Retrieved April 12, 2008.

- ^ Newman, Andy (August 31, 2006). "A Choice for New York Priests in Abuse Cases". The New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2008.

- ^ Grossman, Cathy Lynn. "Survey: More clergy abuse cases than previously thought." USA Today (February 10, 2004). Retrieved February 12, 2012.

- ^ a b Owen, Richard (January 7, 2008). "Pope calls for continuous prayer to rid priesthood of paedophilia". Times Online UK edition. London: Times Newspapers Ltd. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ a b John Jay College of Criminal Justice (2004), The Nature and Scope of Sexual Abuse of Minors by Catholic Priests and Deacons in the United States 1950–2002 (PDF), United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, ISBN 1-57455-627-4, retrieved February 7, 2012

- ^ a b Steinfels, p. 40–46.

- ^ Frawley-ODea, p. 4.

- ^ a b Filteau, Jerry (2004). "Report says clergy sexual abuse brought 'smoke of Satan' into church". Catholic News Service. Retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Walsh, p. 62.

- ^ a b United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (2005). "Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People". United States Conference of Catholic Bishops. Retrieved October 8, 2007.

- ^ Pope Benedict XVI (2005). "Instruction Concerning the Criteria for the Discernment of Vocations with regard to Persons with Homosexual Tendencies in view of their Admission to the Seminary and to Holy Orders". Vatican. Retrieved March 9, 2008.

- ^ "Scandals in the church: The Bishops' Decisions; The Bishops' Charter for the Protection of Children and Young People". The New York Times. June 15, 2002. Retrieved February 12, 2008.

- ^ U.S. Catholic Bishops – Catechism of the Catholic Church

- ^ CCC 2357

- ^ CCC 2370

- ^ CCC 2272

- ^ CCC 2353

- ^ Dugger, Carol (May 18, 2006). "Why is Kenya's AIDS rate plummeting?". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ "Talking Point | Is the Vatican wrong on population control?". BBC News. July 9, 1999. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ Paul VI. "Humanae Vitae – Encyclical Letter of His Holiness Paul VI on the regulation of birth, 25 July 1968". Vatican.va. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Contraception and Sterilization". Catholic.com. August 10, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Birth Control". Catholic.com. August 10, 2004. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ "Catechism of the Catholic Church", see "The various forms of chastity" section.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church: Chastity and homosexuality

- ^ Pope approves barring gay seminarians

References

- Ellis, John Tracy. Documents of American Catholic History 2nd ed. (1956).

Further reading

- Abell, Aaron. American Catholicism and Social Action: A Search for Social Justice, 1865–1950 (1960).

- Carroll, Michael P. American Catholics in the Protestant Imagination: Rethinking the Academic Study of Religion (2007).

- Catholic Encyclopedia, (1913) online edition complete coverage by Catholic scholars; the articles were written about 100 years ago

- Curran, Robert Emmett. Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574-1783 (2014)

- Dolan, Jay P. The Immigrant Church: New York Irish and German Catholics, 1815–1865 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1975).

- Dolan, Jay P. In Search of an American Catholicism: A History of Religion and Culture in Tension (2003)

- Donovan, Grace. "Immigrant Nuns: Their Participation in the Process of Americanization," in Catholic Historical Review 77, 1991, 194–208.

- Ebaugh, Helen Rose, ed., Vatican II and American Catholicism: Twenty-five Years Later (1991).

- Ellis, J.T. American Catholicism (2nd ed. 1969).

- Fialka, John J. Sisters: Catholic Nuns and the Making of America (2003).

- Fogarty, Gerald P., S.J. Commonwealth Catholicism: A History of the Catholic Church in Virginia, ISBN 978-0-268-02264-8.

- Greeley, Andrew. "The Demography of American Catholics, 1965–1990" in The Sociology of Andrew Greeley (1994).

- Lazerson, Marvin (1977). "Understanding American Catholic Educational History". History of Education Quarterly. 17 (3): 297–317. doi:10.2307/367880. JSTOR 367880.

- Marty, Martin E. Modern American Religion, Vol. 1: The Irony of It All, 1893–1919 (1986); Modern American Religion. Vol. 2: The Noise of Conflict, 1919–1941 (1991); Modern American Religion, Volume 3: Under God, Indivisible, 1941–1960 (1999), Protestant perspective by leading historian

- Maynard, Theodore The Story of American Catholicism, (2 vol. 1960), old fashioned chronology

- Morris, Charles R. American Catholic: The Saints and Sinners Who Built America's Most Powerful Church (1998), a standard history

- New Catholic 'Encyclopedia (1967), complete coverage of all topics by Catholic scholars

- Raiche, C.S.J., Annabelle, and Ann Marie Biermaier, O.S.B. They Came to Teach: The Story of Sisters Who Taught in Parochial Schools and Their Contribution to Elementary Education in Minnesota (St. Cloud, Minnesota: North Star Press, 1994) 271pp.

- O'Toole, James M. The Faithful: A History of Catholics in America (2008) excerpt and text search

- Perko, F. Michael (2000). "Religious Schooling In America: An Historiographic Reflection". History of Education Quarterly. 40 (3): 320–338. doi:10.2307/369556. JSTOR 369556.

- Poyo, Gerald E. Cuban Catholics in the United States, 1960–1980: Exile and Integration (2007).

- Sanders, James W. The Education of an urban Minority: Catholics in Chicago, 1833–1965 (1977).

- Schroth, Raymond A. The American Jesuits: A History (2007).

- Walch, Timothy. Parish School: American Catholic Parochial Education from Colonial Times to the Present (1996).

Historiography

- Gleason, Philip. "The Historiography of American Catholicism as Reflected in The Catholic Historical Review, 1915–2015." Catholic Historical Review 101#2 (2015) pp: 156-222. online

- Thomas, J. Douglas. "A Century of American Catholic History." US Catholic Historian (1987): 25-49. in JSTOR