Niya ruins

Cadota 尼雅 | |

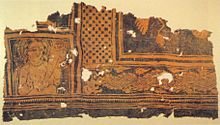

Textile from Niya, showing influences from the East and the West. | |

| Location | Xinjiang, China |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°01′17″N 82°44′15″E / 38.021400°N 82.737600°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Abandoned | 4th to 5th century[1] |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | In ruins |

The Niya ruins (simplified Chinese: 尼雅遗址; traditional Chinese: 尼雅遺址; pinyin: Níyǎ Yízhǐ), is an archaeological site located about 115 km (71 mi) north of modern Niya Town on the southern edge of the Tarim Basin in modern-day Xinjiang, China. The ancient site was known in its native language as Caḍ́ota[citation needed], and in Chinese during the Han dynasty as Jingjue (Chinese: 精絕; pinyin: Jīngjué, Old Chinese tseng-dzot, similar to Caḍ́ota[citation needed]). Numerous ancient archaeological artifacts have been uncovered at the site.

Niya was once a major commercial center on an oasis on the southern branch of the Silk Road in the southern Taklamakan Desert. During ancient times camel caravans would cut through, carrying goods from China to Central Asia.[2][3]

History

[edit]In Hanshu, an independent oasis state called Jingjue, generally thought to be Niya, is mentioned:

The seat of the king's government is the town of Jingjue, and it is distant by 8,820 li [probably 3,667 km/2,279 miles] from Ch'ang-an. There are 480 households, 3,350 individuals with 500 persons able to bear arm. [There are the following officials] the commandant of Jingjue, the leaders of the left and the right and an interpreter-in-chief.

— Hanshu, chapter 96a, translation from Hulsewé 1979.[4]

Niya became part of Loulan Kingdom by the third century. Towards the end of the fourth century it was under Chinese suzerainty. Later it was conquered by Tibet.[5]

Excavations

[edit]

In 1900, Aurel Stein set out on an expedition to western China and the Taklamakan Desert. In Niya he excavated several groups of dwellings, and found 100 wooden tablets written in 105 CE. These tablets bore clay seals, official orders and letters written in Kharoshthi, an early Indic script, dating them to the Kushan empire, or to Gandharan migrants influenced by Kushan and Indian bureaucratic traditions.[6][7] Stein also found a series of clay seals with impressions of Athena Alkidemos, together with others representing Eros, Heracles, or a different version of Athena.[8] Other finds include coins and documents dating from the Han dynasty, Roman coins, an ancient mouse trap, a walking stick, part of a guitar, a bow in working order, a carved stool, an elaborately-designed rug and other textile fragments, as well as many other household objects such as wooden furniture with elaborate carving, pottery, Chinese basketry and lacquer ware.[6][7][9] Aurel Stein visited Niya four times between 1901 and 1931.

Official approval for joint Sino-Japanese archaeological excavations at the site was given in 1994. Researchers have now found remains of human habitation including approximately 100 dwellings, burial areas, sheds for animals, orchards, gardens, and agricultural fields. They have also found in the dwellings well-preserved tools such as iron axes and sickles, wooden clubs, pottery urns and jars of preserved crops. The human remains found there have led to speculation on the origins of these peoples.[10]

In 2007, when the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology’s research group on Niya was editing the third volume of the Report on the Sino-Japanese Joint Expedition in Niya,2 they carefully examined a “parchment text” found in Nya. After the string was untied, it was found that the paper had been used to wrap up a powder of vegetable origin, perhaps spices or medicine. When the powder was removed, a text written in black ink in a clear script was visible. Noting that the writing appeared to be the same as that of the Sogdian “Ancient Letters” found near Dunhuang, which were written in the early fourth century,3 and other Sogdian fragments of similar date found at Loulan, the local archaeologists were able to determine that this new fragment was also written in early Sogdian script.[11]

Some archeological findings from the ruins of Niya are housed in the Tokyo National Museum.[2] Others are part of the Stein collection in the British Museum, the British Library, and the National Museum in New Delhi.

Ancient texts included the mention and names of various regional rulers.[12]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Tang, Ye-Na; Li, Xiao; Yao, Yi-Feng; Ferguson, David Kay; Li, Cheng-Sen (2014-01-27). "Environmental Reconstruction of Tuyoq in the Fifth Century and Its Bearing on Buddhism in Turpan, Xinjiang, China". PLoS ONE. 9 (1): e86363. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0086363. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3903531. PMID 24475109.

- ^ a b Boulnois, Luce (2005). Silk Road: Monks, Warriors & Merchants. Hong Kong: Odessey Books & Guides. pp. 458, 501. ISBN 962-217-721-2.

- ^ "The Most Important Findings of Niya in Taklamakan". The Silk Road. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Hulsewé, A. F. P. (1979). China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. Brill, Leiden. pp. 93–94. ISBN 90-04-05884-2.

- ^ Susan Whitfield (2004). "Krorain: Settlements in the Desert (Niya and the Oases of Kroraina)". The Silk Road: Trade, Travel, War and Faith. The British Library. ISBN 1-932476-12-1.

- ^ a b "An Archeologist Follows His Dreams to Asia". Archived from the original on 2009-02-13. Retrieved 2012-05-16.

- ^ a b "Sir Aurel Stein & the Silk Road finds - Akterek, Balawaste, Chalma-Kazan, Darabzandong, Farhad-Beg-yailaki, Kara-Yantak, Karadong, Khadalik, Khotan, Mazartagh, Mazartoghrak, Niya, Siyelik and Yotkan". Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Christopoulos, Lucas (August 2021). "Hellenes and Romans in Ancient China" (PDF). Sino-Platonic Papers. 230.

- ^ "New Delhi : Aurel Stein Collection :: Niya".

- ^ "Niya yields buried secrets". China Daily. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

- ^ Sims-Williams, N., & Bi, B. (2018). "A Sogdian Fragment from Niya". In Great Journeys across the Pamir Mountains. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004362253_007

- ^ 论尼雅遗址的时代

External links

[edit]