Joan of Arc

Joan of Arc | |

|---|---|

Historiated initial depicting Johan of Arc from Archives Nationales, Paris, AE II 2490, allegedly dated to the second half of the 15th century but presumably art forgery painted in the late 19th or early 20th centuries, according to medievalist Philippe Contamine.[1] | |

| Martyr and Holy Virgin | |

| Born | Jeanne d'Arc (modern French) circa 1412 Domrémy, Duchy of Bar, Kingdom of France |

| Died | 30 May 1431 (aged approx. 19)

|

| Venerated in | |

| Beatified | 18 April 1909, Saint Peter's Basilica, Rome by Pope Pius X |

| Canonized | 16 May 1920, Saint Peter's Basilica, Rome by Pope Benedict XV |

| Feast | 30 May |

| Attributes | Armor, banner, sword |

| Patronage | France; martyrs; captives; military personnel; people ridiculed for their piety; prisoners; soldiers; women who have served in the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service); and Women's Army Corps |

Signature of Joan of Arc  Coat of arms of Joan of Arc | |

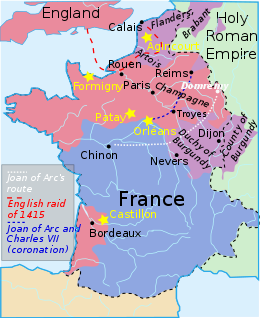

Joan of Arc (French: Jeanne d'Arc[3][4] pronounced [ʒan daʁk]; c. 1412 – 30 May 1431),[5] nicknamed "The Maid of Orléans" (Template:Lang-fr), is considered a heroine of France for her role during the Lancastrian phase of the Hundred Years' War, and was canonized as a Catholic saint. She was born to Jacques d'Arc and Isabelle Romée, a peasant family, at Domrémy in the Vosges of northeast France. Joan claimed to have received visions of the archangel Michael, Saint Margaret, and Saint Catherine of Alexandria instructing her to support Charles VII and recover France from English domination late in the Hundred Years' War. The as-yet-unanointed King Charles VII sent Joan to the Siege of Orléans as part of a relief army. She gained prominence after the siege was lifted only nine days later. Several additional swift victories led to Charles VII's consecration at Reims. This long-awaited event boosted French morale and paved the way for the final French victory at Castillon in 1453.

On 23 May 1430, she was captured at Compiègne by the Burgundian faction, a group of French nobles allied with the English. She was later handed over to the English[6] and put on trial by the pro-English bishop Pierre Cauchon on a variety of charges.[7] After Cauchon declared her guilty, she was burned at the stake on 30 May 1431, dying at about nineteen years of age.[8]

In 1456, an inquisitorial court authorized by Pope Callixtus III examined the trial, debunked the charges against her, pronounced her innocent, and declared her a martyr.[8] In the 16th century she became a symbol of the Catholic League, and in 1803 she was declared a national symbol of France by the decision of Napoleon Bonaparte.[9] She was beatified in 1909 and canonized in 1920. Joan of Arc is one of the nine secondary patron saints of France, along with Saint Denis, Saint Martin of Tours, Saint Louis, Saint Michael, Saint Rémi, Saint Petronilla, Saint Radegund and Saint Thérèse of Lisieux.

Joan of Arc has remained a popular figure in literature, painting, sculpture, and other cultural works since the time of her death, and many famous writers, playwrights, filmmakers, artists, and composers have created, and continue to create, cultural depictions of her.

Background

The Hundred Years' War had begun in 1337 as an inheritance dispute over the French throne, interspersed with occasional periods of relative peace. Nearly all the fighting had taken place in France, and the English army's use of chevauchée tactics (destructive "scorched earth" raids) had devastated the economy.[10] The French population had not regained its former size since the Black Death of the mid-14th century, and its merchants were isolated from foreign markets. Before the appearance of Joan of Arc, the English had nearly achieved their goal of a dual monarchy under English control and the French army had not achieved any major victories for a generation. In the words of DeVries, "The kingdom of France was not even a shadow of its thirteenth-century prototype."[11]

The French king at the time of Joan's birth, Charles VI, suffered from bouts of insanity[12] and was often unable to rule. The king's brother Louis, Duke of Orléans, and the king's cousin John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, quarreled over the regency of France and the guardianship of the royal children. This dispute included accusations that Louis was having an extramarital affair with the queen, Isabeau of Bavaria, and allegations that John the Fearless kidnapped the royal children.[13] The conflict climaxed with the assassination of the Duke of Orléans in 1407 on the orders of the Duke of Burgundy.[14][15]

The young Charles of Orléans succeeded his father as duke and was placed in the custody of his father-in-law, the Count of Armagnac. Their faction became known as the "Armagnac" faction, and the opposing party led by the Duke of Burgundy was called the "Burgundian faction". Henry V of England took advantage of these internal divisions when he invaded the kingdom in 1415, winning a dramatic victory at Agincourt on 25 October and subsequently capturing many northern French towns during a later campaign in 1417.[16] In 1418 Paris was taken by the Burgundians, who massacred the Count of Armagnac and about 2,500 of his followers.[17] The future French king, Charles VII, assumed the title of Dauphin—the heir to the throne—at the age of fourteen, after all four of his older brothers had died in succession.[18] His first significant official act was to conclude a peace treaty with the Duke of Burgundy in 1419. This ended in disaster when Armagnac partisans assassinated John the Fearless during a meeting under Charles's guarantee of protection. The new duke of Burgundy, Philip the Good, blamed Charles for the murder and entered into an alliance with the English. The allied forces conquered large sections of France.[19]

In 1420 the queen of France, Isabeau of Bavaria, signed the Treaty of Troyes, which granted the succession of the French throne to Henry V and his heirs instead of her son Charles. This agreement revived suspicions that the Dauphin was the illegitimate product of Isabeau's rumored affair with the late duke of Orléans rather than the son of King Charles VI.[20] Henry V and Charles VI died within two months of each other in 1422, leaving an infant, Henry VI of England, the nominal monarch of both kingdoms. Henry V's brother, John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, acted as regent.[21]

By the time Joan of Arc began to influence events in 1429, nearly all of northern France and some parts of the southwest were under Anglo-Burgundian control. The English controlled Paris and Rouen while the Burgundian faction controlled Reims, which had served as the traditional site for the coronation of French kings. This was an important consideration since neither claimant to the throne of France had been anointed or crowned yet. Since 1428 the English had been conducting a siege of Orléans, one of the few remaining cities still loyal to Charles VII and an important objective since it held a strategic position along the Loire River, which made it the last obstacle to an assault on the remainder of Charles VII's territory. In the words of one modern historian, "On the fate of Orléans hung that of the entire kingdom."[22] No one was optimistic that the city could long withstand the siege.[23] For generations, there had been prophecies in France which promised the nation would be saved by a virgin from the "borders of Lorraine" "who would work miracles" and "that France will be lost by a woman and shall thereafter be restored by a virgin".[24] The second prophecy predicting France would be "lost" by a woman was taken to refer to Isabeau's role in signing the Treaty of Troyes.[25]

Biography

Joan was the daughter of Jacques d'Arc and Isabelle Romée,[26] living in Domrémy, a village which was then in the French part of the Duchy of Bar.[27][28] Joan's parents owned about 50 acres (20 hectares) of land and her father supplemented his farming work with a minor position as a village official, collecting taxes and heading the local watch.[29] They lived in an isolated patch of eastern France that remained loyal to the French crown despite being surrounded by pro-Burgundian lands. Several local raids occurred during her childhood and on one occasion her village was burned. Joan was illiterate and it is believed that her letters were dictated by her to scribes and she signed her letters with the help of others.[30]

At her trial, Joan stated that she was about 19 years old, which implies she thought she was born around 1412. She later testified that she experienced her first vision in 1425 at the age of 13, when she was in her "father's garden"[31] and saw visions of figures she identified as Saint Michael, Saint Catherine, and Saint Margaret, who told her to drive out the English and take the Dauphin to Reims for his consecration. She said she cried when they left, as they were so beautiful.[32]

At the age of 16, she asked a relative named Durand Lassois to take her to the nearby town of Vaucouleurs, where she petitioned the garrison commander, Robert de Baudricourt, for an armed escort to take her to the French Royal Court at Chinon. Baudricourt's sarcastic response did not deter her.[33] She returned the following January and gained support from two of Baudricourt's soldiers: Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy.[34] According to Jean de Metz, she told him that "I must be at the King's side ... there will be no help (for the kingdom) if not from me. Although I would rather have remained spinning [wool] at my mother's side ... yet must I go and must I do this thing, for my Lord wills that I do so."[35] Under the auspices of Jean de Metz and Bertrand de Poulengy, she was given a second meeting, where she made a prediction about a military reversal at the Battle of Rouvray near Orléans several days before messengers arrived to report it.[36] According to the Journal du Siége d'Orléans, which portrays Joan as a miraculous figure, Joan came to know of the battle through "Divine grace" while tending her flocks in Lorraine and used this divine revelation to persuade Baudricourt to take her to the Dauphin.[37]

Rise

Robert de Baudricourt granted Joan an escort to visit Chinon after news from Orleans confirmed her assertion of the defeat. She made the journey through hostile Burgundian territory disguised as a male soldier,[38] a fact that would later lead to charges of "cross-dressing" against her, although her escort viewed it as a normal precaution. Two of the members of her escort said they and the people of Vaucouleurs provided her with this clothing, and had suggested it to her.[39]

Joan's first meeting with Charles took place at the Royal Court in the town of Chinon in 1429, when she was aged 17 and he 26. After arriving at the Court she made a strong impression on Charles during a private conference with him. During this time Charles' mother-in-law Yolande of Aragon was planning to finance a relief expedition to Orléans. Joan asked for permission to travel with the army and wear protective armor, which was provided by the Royal government. She depended on donated items for her armor, horse, sword, banner, and other items utilized by her entourage. Historian Stephen W. Richey explains her attraction to the royal court by pointing out that they may have viewed her as the only source of hope for a regime that was near collapse:

After years of one humiliating defeat after another, both the military and civil leadership of France were demoralized and discredited. When the Dauphin Charles granted Joan's urgent request to be equipped for war and placed at the head of his army, his decision must have been based in large part on the knowledge that every orthodox, every rational option had been tried and had failed. Only a regime in the final straits of desperation would pay any heed to an illiterate farm girl who claimed that the voice of God was instructing her to take charge of her country's army and lead it to victory.[40]

Upon her arrival on the scene, Joan effectively turned the longstanding Anglo-French conflict into a religious war,[42] a course of action that was not without risk. Charles' advisers were worried that unless Joan's orthodoxy could be established beyond doubt—that she was not a heretic or a sorceress—Charles' enemies could easily make the allegation that his crown was a gift from the devil. To circumvent this possibility, the Dauphin ordered background inquiries and a theological examination at Poitiers to verify her morality. In April 1429, the commission of inquiry "declared her to be of irreproachable life, a good Christian, possessed of the virtues of humility, honesty and simplicity."[42] The theologians at Poitiers did not render a decision on the issue of divine inspiration; rather, they informed the Dauphin that there was a "favorable presumption" to be made on the divine nature of her mission. This convinced Charles, but they also stated that he had an obligation to put Joan to the test. "To doubt or abandon her without suspicion of evil would be to repudiate the Holy Spirit and to become unworthy of God's aid", they declared.[43] They recommended that her claims should be put to the test by seeing if she could lift the siege of Orléans as she had predicted.[43]

She arrived at the besieged city of Orléans on 29 April 1429. Jean d'Orléans, the acting head of the ducal family of Orléans on behalf of his captive half-brother, initially excluded her from war councils and failed to inform her when the army engaged the enemy.[44] However, his decision to exclude her did not prevent her presence at most councils and battles.[45] The extent of her actual military participation and leadership is a subject of debate among historians. On the one hand, Joan stated that she carried her banner in battle and had never killed anyone,[46] preferring her banner "forty times" better than a sword;[47] and the army was always directly commanded by a nobleman, such as the Duke of Alençon for example. On the other hand, many of these same noblemen stated that Joan had a profound effect on their decisions since they often accepted the advice she gave them, believing her advice was divinely inspired.[48] In either case, historians agree that the army enjoyed remarkable success during her brief time with it.[49]

Military campaigns

Joan on horseback in a 1505 illustration | |

| Nickname(s) | The Maid of Orléans |

| Allegiance | Kingdom of France |

| Conflict | Hundred Years' War |

The appearance of Joan of Arc at Orléans coincided with a sudden change in the pattern of the siege. During the five months before her arrival, the defenders had attempted only one offensive assault, which had ended in defeat. On 4 May, however, the Armagnacs attacked and captured the outlying fortress of Saint Loup (bastille de Saint-Loup), followed on 5 May by a march to a second fortress called Saint-Jean-le-Blanc, which was found deserted. When English troops came out to oppose the advance, a rapid cavalry charge drove them back into their fortresses, apparently without a fight.

The Armagnacs then attacked and captured an English fortress built around a monastery called Les Augustins. That night, Armagnac troops maintained positions on the south bank of the river before attacking the main English stronghold, called "les Tourelles", on the morning of 7 May.[50] Contemporaries acknowledged Joan as the heroine of the engagement. She was wounded by an arrow between the neck and shoulder while holding her banner in the trench outside les Tourelles, but later returned to encourage a final assault that succeeded in taking the fortress. The English retreated from Orléans the next day, and the siege was over.[51]

At Chinon and Poitiers, Joan had declared that she would provide a sign at Orléans. The lifting of the siege was interpreted by many people to be that sign, and it gained her the support of prominent clergy such as the Archbishop of Embrun and the theologian Jean Gerson, both of whom wrote supportive treatises immediately following this event.[52] To the English, the ability of this peasant girl to defeat their armies was regarded as proof that she was possessed by the Devil; the British medievalist Beverly Boyd noted that this charge was not just propaganda, and was sincerely believed since the idea that God was supporting the French via Joan was distinctly unappealing to an English audience.[53]

The sudden victory at Orléans also led to many proposals for further offensive action. Joan persuaded Charles VII to allow her to accompany the army with Duke John II of Alençon, and she gained royal permission for her plan to recapture nearby bridges along the Loire as a prelude to an advance on Reims and the consecration of Charles VII. This was a bold proposal because Reims was roughly twice as far away as Paris and deep within enemy territory.[54] The English expected an attempt to recapture Paris or an attack on Normandy.[citation needed]

The Duke of Alençon accepted Joan's advice concerning strategy. Other commanders including Jean d'Orléans had been impressed with her performance at Orléans and became her supporters. Alençon credited her with saving his life at Jargeau, where she warned him that a cannon on the walls was about to fire at him.[55] During the same siege she withstood a blow from a stone that hit her helmet while she was near the base of the town's wall. The army took Jargeau on 12 June, Meung-sur-Loire on 15 June, and Beaugency on 17 June.[citation needed]

The English army withdrew from the Loire Valley and headed north on 18 June, joining with an expected unit of reinforcements under the command of Sir John Fastolf. Joan urged the Armagnacs to pursue, and the two armies clashed southwest of the village of Patay. The battle at Patay might be compared to Agincourt in reverse. The French vanguard attacked a unit of English archers who had been placed to block the road. A rout ensued that decimated the main body of the English army and killed or captured most of its commanders. Fastolf escaped with a small band of soldiers and became the scapegoat for the humiliating English defeat. The French suffered minimal losses.[56]

The French army left Gien on 29 June on the march toward Reims and accepted the conditional surrender of the Burgundian-held city of Auxerre on 3 July. Other towns in the army's path returned to French allegiance without resistance. Troyes, the site of the treaty that tried to disinherit Charles VII, was the only one to put up even brief opposition. The army was in short supply of food by the time it reached Troyes. But the army was in luck: a wandering friar named Brother Richard had been preaching about the end of the world at Troyes and convinced local residents to plant beans, a crop with an early harvest. The hungry army arrived as the beans ripened.[57] Troyes capitulated after a bloodless four-day siege.[58]

Reims opened its gates to the army on 16 July 1429. The consecration took place the following morning. Although Joan and the Duke of Alençon urged a prompt march toward Paris, the royal court preferred to negotiate a truce with Duke Philip of Burgundy. The duke violated the purpose of the agreement by using it as a stalling tactic to reinforce the defense of Paris.[59] The French army marched past a succession of towns near Paris during the interim and accepted the surrender of several towns without a fight. The Duke of Bedford led an English force to confront Charles VII's army at the battle of Montépilloy on 15 August, which resulted in a standoff. The French assault at Paris ensued on 8 September. Despite a wound to the leg from a crossbow bolt, Joan remained in the inner trench of Paris until she was carried back to safety by one of the commanders.[60]

The following morning the army received a royal order to withdraw. Most historians blame French Grand Chamberlain Georges de la Trémoille for the political blunders that followed the consecration.[61] In October, Joan was with the royal army when it took Saint-Pierre-le-Moûtier, followed by an unsuccessful attempt to take La-Charité-sur-Loire in November and December. On 29 December, Joan and her family were ennobled by Charles VII as a reward for her actions.[62][63]

Capture

A truce with England during the following few months left Joan with little to do. On 23 March 1430, she dictated a threatening letter to the Hussites, a dissident group which had broken with the Catholic Church on a number of doctrinal points and had defeated several previous crusades sent against them. Joan's letter promises to "remove your madness and foul superstition, taking away either your heresy or your lives."[64] Joan, an ardent Catholic who hated all forms of heresy, also sent a letter challenging the English to leave France and go with her to Bohemia to fight the Hussites, an offer that went unanswered.[65]

The truce with England quickly came to an end. Joan traveled to Compiègne the following May to help defend the city against an English and Burgundian siege. On 23 May 1430 she was with a force that attempted to attack the Burgundian camp at Margny north of Compiègne, but was ambushed and captured.[66] When the troops began to withdraw toward the nearby fortifications of Compiègne after the advance of an additional force of 6,000 Burgundians,[66] Joan stayed with the rear guard. Burgundian troops surrounded the rear guard, and she was pulled off her horse by an archer.[67] She agreed to surrender to a pro-Burgundian nobleman named Lionel of Wandomme, a member of Jean de Luxembourg's unit.[68]

Joan was imprisoned by the Burgundians at Beaurevoir Castle. She made several escape attempts, on one occasion jumping from her 70-foot (21 m) tower, landing on the soft earth of a dry moat, after which she was moved to the Burgundian town of Arras.[69] The English negotiated with their Burgundian allies to transfer her to their custody, with Bishop Pierre Cauchon of Beauvais, an English partisan, assuming a prominent role in these negotiations and her later trial.[70][better source needed] The final agreement called for the English to pay the sum of 10,000 livres tournois[71] to obtain her from Jean de Luxembourg, a member of the Council of Duke Philip of Burgundy.[citation needed]

The English moved Joan to the city of Rouen, which served as their main headquarters in France. The Armagnacs attempted to rescue her several times by launching military campaigns toward Rouen while she was held there. One campaign occurred during the winter of 1430–1431, another in March 1431, and one in late May shortly before her execution. These attempts were beaten back.[72] Charles VII threatened to "exact vengeance" upon Burgundian troops whom his forces had captured and upon "the English and women of England" in retaliation for their treatment of Joan.[73]

Trial

The trial for heresy was politically motivated. The tribunal was composed entirely of pro-English and Burgundian clerics, and overseen by English commanders including the Duke of Bedford and the Earl of Warwick.[74] In the words of the British medievalist Beverly Boyd, the trial was meant by the English Crown to be "a ploy to get rid of a bizarre prisoner of war with maximum embarrassment to their enemies".[53] Legal proceedings commenced on 9 January 1431 at Rouen, the seat of the English occupation government.[75] The procedure was suspect on a number of points, which would later provoke criticism of the tribunal by the chief inquisitor who investigated the trial after the war.[76]

Under ecclesiastical law, Bishop Cauchon lacked jurisdiction over the case.[77] Cauchon owed his appointment to his partisan support of the English Crown, which financed the trial. The low standard of evidence used in the trial also violated inquisitorial rules.[78] Clerical notary Nicolas Bailly, who was commissioned to collect testimony against Joan, could find no adverse evidence.[79] Without such evidence the court lacked grounds to initiate a trial. Opening a trial anyway, the court also violated ecclesiastical law by denying Joan the right to a legal adviser. In addition, stacking the tribunal entirely with pro-English clergy violated the medieval Church's requirement that heresy trials be judged by an impartial or balanced group of clerics. Upon the opening of the first public examination, Joan complained that those present were all partisans against her and asked for "ecclesiastics of the French side" to be invited in order to provide balance. This request was denied.[80]

The Vice-Inquisitor of Northern France (Jean Lemaitre) objected to the trial at its outset, and several eyewitnesses later said he was forced to cooperate after the English threatened his life.[81] Some of the other clergy at the trial were also threatened when they refused to cooperate, including a Dominican friar named Isambart de la Pierre.[82] These threats, and the domination of the trial by a secular government, were violations of the Church's rules and undermined the right of the Church to conduct heresy trials without secular interference.[citation needed]

The trial record contains statements from Joan that the eyewitnesses later said astonished the court, since she was an illiterate peasant and yet was able to evade the theological pitfalls the tribunal had set up to entrap her. The transcript's most famous exchange is an exercise in subtlety: "Asked if she knew she was in God's grace, she answered, 'If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me. I should be the saddest creature in the world if I knew I were not in His grace.'"[83] The question is a scholarly trap. Church doctrine held that no one could be certain of being in God's grace. If she had answered yes, then she would have been charged with heresy. If she had answered no, then she would have confessed her own guilt. The court notary Boisguillaume later testified that at the moment the court heard her reply, "Those who were interrogating her were stupefied."[84]

Several members of the tribunal later testified that important portions of the transcript were falsified by being altered in her disfavor. Under Inquisitorial guidelines, Joan should have been confined in an ecclesiastical prison under the supervision of female guards (i.e., nuns). Instead, the English kept her in a secular prison guarded by their own soldiers. Bishop Cauchon denied Joan's appeals to the Council of Basel and the Pope, which should have stopped his proceeding.[85]

The twelve articles of accusation which summarized the court's findings contradicted the court record, which had already been doctored by the judges.[86][87] Under threat of immediate execution, the illiterate defendant signed an abjuration document that she did not understand. The court substituted a different abjuration in the official record.[88]

Cross-dressing charge

Heresy was a capital crime only for a repeat offense; therefore, a repeat offense of "cross-dressing" was now arranged by the court, according to the eyewitnesses. Joan agreed to wear feminine clothing when she abjured, which created a problem. According to the later descriptions of some of the tribunal members, she had previously been wearing soldiers' clothing in prison. Since wearing men's hosen enabled her to fasten her hosen, boots and doublet together, this deterred rape by making it difficult for her guards to pull her clothing off. She was evidently afraid to give up this clothing even temporarily because it was likely to be confiscated by the judge and she would thereby be left without protection.[89][90] A woman's dress offered no such protection. A few days after her abjuration, when she was forced to wear a dress, she told a tribunal member that "a great English lord had entered her prison and tried to take her by force."[91] She resumed male attire either as a defense against molestation or, in the testimony of Jean Massieu, because her dress had been taken by the guards and she was left with nothing else to wear.[92]

Her resumption of male military clothing was labeled a relapse into heresy for cross-dressing, although this would later be disputed by the inquisitor who presided over the appeals court that examined the case after the war. Medieval Catholic doctrine held that cross-dressing should be evaluated based on context, as stated in the Summa Theologica by St. Thomas Aquinas, which says that necessity would be a permissible reason for cross-dressing.[93] This would include the use of clothing as protection against rape if the clothing would offer protection. In terms of doctrine, she had been justified in disguising herself as a pageboy during her journey through enemy territory, and she was justified in wearing armor during battle and protective clothing in camp and then in prison. The Chronique de la Pucelle states that it deterred molestation while she was camped in the field. When her soldiers' clothing was not needed while on campaign, she was said to have gone back to wearing a dress.[94] Clergy who later testified at the posthumous appellate trial affirmed that she continued to wear male clothing in prison to deter molestation and rape.[89]

Joan referred the court to the Poitiers inquiry when questioned on the matter. The Poitiers record no longer survives, but circumstances indicate the Poitiers clerics had approved her practice.[95] She also kept her hair cut short through her military campaigns and while in prison. Her supporters, such as the theologian Jean Gerson, defended her hairstyle for practical reasons, as did Inquisitor Brehal later during the appellate trial.[96] Nonetheless, at the trial in 1431 she was condemned and sentenced to die. Boyd described Joan's trial as so "unfair" that the trial transcripts were later used as evidence for canonizing her in the 20th century.[53]

Execution

Eyewitnesses described the scene of the execution by burning on 30 May 1431. Tied to a tall pillar at the Vieux-Marché in Rouen, she asked two of the clergy, Fr. Martin Ladvenu and Fr. Isambart de la Pierre, to hold a crucifix before her. An English soldier also constructed a small cross that she put in the front of her dress. After she died, the English raked back the coals to expose her charred body so that no one could claim she had escaped alive. They then burned the body twice more, to reduce it to ashes and prevent any collection of relics, and cast her remains into the Seine River.[97] The executioner, Geoffroy Thérage, later stated that he "greatly feared to be damned for he had burned a holy woman."[98]

Posthumous events

The Hundred Years' War continued for twenty-two years after her death. Charles VII retained legitimacy as the king of France in spite of a rival coronation held for Henry VI at Notre-Dame cathedral in Paris on 16 December 1431, the boy's tenth birthday. Before England could rebuild its military leadership and force of longbowmen lost in 1429, the country lost its alliance with Burgundy when the Treaty of Arras was signed in 1435. The Duke of Bedford died the same year and Henry VI became the youngest king of England to rule without a regent. His weak leadership was probably the most important factor in ending the conflict. Kelly DeVries argues that Joan of Arc's aggressive use of artillery and frontal assaults influenced French tactics for the rest of the war.[99]

In 1452, during the posthumous investigation into her execution, the Church declared that a religious play in her honor at Orléans would allow attendees to gain an indulgence (remission of temporal punishment for sin) by making a pilgrimage to the event.[100]

Retrial

A posthumous retrial opened after the war ended. Pope Callixtus III authorized this proceeding, also known as the "nullification trial", at the request of Inquisitor-General Jean Bréhal and Joan's mother Isabelle Romée. The purpose of the trial was to investigate whether the trial of condemnation and its verdict had been handled justly and according to canon law. Investigations started with an inquest by Guillaume Bouillé, a theologian and former rector of the University of Paris (Sorbonne).

Bréhal conducted an investigation in 1452. A formal appeal followed in November 1455. The appellate process involved clergy from throughout Europe and observed standard court procedure. A panel of theologians analyzed testimony from 115 witnesses. Bréhal drew up his final summary in June 1456, which describes Joan as a martyr and implicated the late Pierre Cauchon with heresy[101] for having convicted an innocent woman in pursuit of a secular vendetta. The technical reason for her execution had been a Biblical clothing law.[102] The nullification trial reversed the conviction in part because the condemnation proceeding had failed to consider the doctrinal exceptions to that stricture. The appellate court declared her innocent on 7 July 1456.[103]

Canonization

Joan of Arc became a symbol of the Catholic League during the 16th century. When Félix Dupanloup was made bishop of Orléans in 1849, he pronounced a fervid panegyric on Joan of Arc, which attracted attention in England as well as France, and he led the efforts which culminated in Joan of Arc's beatification in 1909.[104] She was canonized as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church on 16 May 1920 by Pope Benedict XV in his bull Divina disponente.[105]

Legacy

Joan of Arc became a semi-legendary figure for the four centuries after her death. The main sources of information about her were chronicles. Five original manuscripts of her condemnation trial surfaced in old archives during the 19th century. Soon, historians also located the complete records of her rehabilitation trial, which contained sworn testimony from 115 witnesses, and the original French notes for the Latin condemnation trial transcript. Various contemporary letters also emerged, three of which carry the signature Jehanne in the unsteady hand of a person learning to write.[106] This unusual wealth of primary source material is one reason DeVries declares, "No person of the Middle Ages, male or female, has been the subject of more study."[107]

Joan of Arc came from an obscure village and rose to prominence when she was a teenager, and she did so as an uneducated peasant. The French and English kings had justified the ongoing war through competing interpretations of inheritance law, first concerning Edward III's claim to the French throne and then Henry VI's. The conflict had been a legalistic feud between two related royal families, but Joan transformed it along nationalist lines and gave meaning to appeals such as that of squire Jean de Metz when he asked, "Must the king be driven from the kingdom; and are we to be English?"[34] In the words of Stephen Richey, "She turned what had been a dry dynastic squabble that left the common people unmoved except for their own suffering into a passionately popular war of national liberation."[108] Richey also expresses the breadth of her subsequent appeal:

The people who came after her in the five centuries since her death tried to make everything of her: demonic fanatic, spiritual mystic, naive and tragically ill-used tool of the powerful, creator and icon of modern popular nationalism, adored heroine, saint. She insisted, even when threatened with torture and faced with death by fire, that she was guided by voices from God. Voices or no voices, her achievements leave anyone who knows her story shaking his head in amazed wonder.[108]

From Christine de Pizan to the present, women have looked to Joan as a positive example of a brave and active woman.[109] She operated within a religious tradition that believed an exceptional person from any level of society might receive a divine calling. Some of her most significant aid came from women. King Charles VII's mother-in-law, Yolande of Aragon, confirmed Joan's virginity and financed her departure to Orléans. Joan of Luxembourg, aunt to the count of Luxembourg who held custody of her after Compiègne, alleviated her conditions of captivity and may have delayed her sale to the English. Finally, Anne of Burgundy, the duchess of Bedford and wife to the regent of England, declared Joan a virgin during pretrial inquiries.[110]

Three separate vessels of the French Navy have been named after her, including a helicopter carrier that was retired from active service on 7 June 2010. At present, the French far-right political party Front National holds rallies at her statues, reproduces her image in the party's publications, and uses a tricolor flame partly symbolic of her martyrdom as its emblem. This party's opponents sometimes satirize its appropriation of her image.[111] The French civic holiday in her honour, set in 1920, is the second Sunday of May.[112]

World War I songs include "Joan of Arc, They Are Calling You", and "Joan of Arc's Answer Song".[113][114]

Visions

Joan of Arc's religious visions have remained an ongoing topic of interest. She identified Saint Margaret, Saint Catherine, and Saint Michael as the sources of her revelations, although there is some ambiguity as to which of several identically named saints she intended.

Analysis of her visions is problematic since the main source of information on this topic is the condemnation trial transcript in which she defied customary courtroom procedure about a witness oath and specifically refused to answer every question about her visions. She complained that a standard witness oath would conflict with an oath she had previously sworn to maintain confidentiality about meetings with her king. It remains unknown to what extent the surviving record may represent the fabrications of corrupt court officials or her own possible fabrications to protect state secrets.[115] Some historians sidestep speculation about the visions by asserting that her belief in her calling is more relevant than questions about the visions' ultimate origin.[116]

A number of more recent scholars attempted to explain her visions in psychiatric or neurological terms. Potential diagnoses have included epilepsy, migraine, tuberculosis, and schizophrenia.[117] None of the putative diagnoses have gained consensus support, and many scholars have argued that she did not display any of the objective symptoms that can accompany the mental illnesses which have been suggested, such as schizophrenia. Dr. Philip Mackowiak dismissed the possibility of schizophrenia and several other disorders (Temporal Lobe Epilepsy and ergot poisoning) in a chapter on Joan of Arc in his book Post-Mortem in 2007.[118]

Dr. John Hughes rejected the idea that Joan of Arc suffered from epilepsy in an article in the academic journal Epilepsy & Behavior.[119]

Two experts who analyzed the hypothesis of temporal lobe tuberculoma in the medical journal Neuropsychobiology expressed their misgivings about this claim in the following statement:

It is difficult to draw final conclusions, but it would seem unlikely that widespread tuberculosis, a serious disease, was present in this "patient" whose life-style and activities would surely have been impossible had such a serious disease been present.[120]

In response to another such theory alleging that her visions were caused by bovine tuberculosis as a result of drinking unpasteurized milk, historian Régine Pernoud wrote that if drinking unpasteurized milk could produce such potential benefits for the nation, then the French government should stop mandating the pasteurization of milk.[121]

Joan of Arc gained favor in the court of King Charles VII, who accepted her as sane. He would have been familiar with the signs of madness because his own father, Charles VI, had suffered from it. Charles VI was popularly known as "Charles the Mad", and much of France's political and military decline during his reign could be attributed to the power vacuum that his episodes of insanity had produced. The previous king had believed he was made of glass, a delusion no courtier had mistaken for a religious awakening. Fears that King Charles VII would manifest the same insanity may have factored into the attempt to disinherit him at Troyes. This stigma was so persistent that contemporaries of the next generation would attribute to inherited madness the breakdown that England's King Henry VI was to suffer in 1453: Henry VI was nephew to Charles VII and grandson to Charles VI. The court of Charles VII was shrewd and skeptical on the subject of mental health.[122][123] Upon Joan's arrival at Chinon the royal counselor Jacques Gélu cautioned,

One should not lightly alter any policy because of conversation with a girl, a peasant ... so susceptible to illusions; one should not make oneself ridiculous in the sight of foreign nations.

Joan remained astute to the end of her life and the rehabilitation trial testimony frequently marvels at her astuteness:

Often they [the judges] turned from one question to another, changing about, but, notwithstanding this, she answered prudently, and evinced a wonderful memory.[124]

Her subtle replies under interrogation even forced the court to stop holding public sessions.[84]

Alleged relics

In 1867, a jar was found in a Paris pharmacy with the inscription "Remains found under the stake of Joan of Arc, virgin of Orleans." They consisted of a charred human rib, carbonized wood, a piece of linen and a cat femur—explained as the practice of throwing black cats onto the pyre of witches. In 2006, Philippe Charlier, a forensic scientist at Raymond Poincaré University Hospital (Garches) was authorized to study the relics. Carbon-14 tests and various spectroscopic analyses were performed, and the results determined that the remains come from an Egyptian mummy from the sixth to the third century BC.[126]

In March 2016 a ring believed to have been worn by Joan, which had passed through the hands of several prominent people including a cardinal, a king, an aristocrat and the daughter of a British physician, was sold at auction to the Puy du Fou, a historical theme park, for £300,000.[127] There is no conclusive proof that she owned the ring, but its unusual design closely matches Joan's own words about her ring at her trial.[128][129] The Arts Council later determined the ring should not have left the United Kingdom. The purchasers appealed, including to Queen Elizabeth II, and the ring was allowed to remain in France. The ring was reportedly first passed to Cardinal Henry Beaufort, who attended Joan's trial and execution in 1431.[130]

Revisionist theories

The standard accounts of the life of Joan of Arc have been challenged by revisionist authors. Claims include: that Joan of Arc was not actually burned at the stake;[131] that she was secretly the half sister of King Charles VII;[132] that she was not a true Christian but a member of a pagan cult;[133] and that most of the story of Joan of Arc is actually a myth.[134]

Footnotes

- ^ (in French) Philippe Contamine, "Remarques critiques sur les étendards de Jeanne d'Arc", Francia, Ostfildern: Jan Thorbecke Verlag, n° 34/1, 2007, p. 199-200.

- ^ "Holy Days". Archived from the original on 26 October 2011.

- ^ Her name was written in a variety of ways, particularly before the mid-19th century. See Pernoud and Clin, pp. 220–21. Her signature appears as "Jehanne" (see www.stjoan-center.com/Album/, parts 47 and 49; it is also noted in Pernoud and Clin).

- ^ In archaic form, Jehanne Darc (Pernoud Clin 1998, pp. 220–221), but also Tarc, Daly or Day (Contamine Bouzy Hélary 2012 pp. 511; 517-519).

- ^ An exact date of birth (6 January, without mention of the year), is uniquely indicated by Perceval de Boulainvilliers, councillor of King Charles VII, in a letter to the duke of Milan. Régine Pernoud's Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 98: "Boulainvilliers tells of her birth in Domrémy, and it is he who gives us an exact date, which may be the true one, saying that she was born on the night of Epiphany, 6 January". However, Marius Sepet has alleged that Boulainvilliers' letter is mythographic and therefore, in his opinion, unreliable (Marius Sepet, "Observations critiques sur l'histoire de Jeanne d'Arc. La lettre de Perceval de Boulainvilliers", in Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes, n°77, 1916, pp. 439–47. Gerd Krumeich shares the same analysis (Gerd Krumeich, "La date de la naissance de Jeanne d'Arc", in De Domremy ... à Tokyo: Jeanne d'Arc et la Lorraine, 2013, pp. 21–31). Colette Beaune emphasizes the mythical character of the Epiphany feast, the peasants' joy and the long rooster crow mentioned by Boulainvilliers (Colette Beaune, Jeanne d'Arc, Paris: Perrin, 2004, ISBN 2-262-01705-0, pp. 26-30). As a medieval peasant, Joan of Arc knew only approximately her age. Olivier Bouzy points out that accuracy birthdates are commonly ignored in the Middle Ages, even within the nobility, except for the princes and kings. Therefore, Boulainvilliers' precise date is quite extraordinary for that time. At least, the year 1412 rates in the chronological range, between 1411 and 1413, referenced by the chronicles, Joan herself and her squire Jean d'Aulon (Olivier Bouzy, Jeanne d'Arc en son siècle, Paris: Fayard, 2013, ISBN 978-2-213-67205-2, pp. 91-93).

- ^ "Le procès de Jeanne d'Arc".

- ^ Régine Pernoud, "Joan of Arc By Herself And Her Witnesses", pp. 179, 220–22

- ^ a b Andrew Ward (2005) Joan of Arc at IMDb

- ^ Joan of Arc: Reality and Myth. Uitgeverij Verloren. 1994. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-6550-412-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ John Aberth, From the Brink of the Apocalypse, Routledge, 2000 ISBN 0-415-92715-3, 978-0-415-92715-4 p. 85

- ^ DeVries, pp. 27–28.

- ^ "Charles VI". Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine; Clin, Marie-Véronique (1999). Joan of Arc: Her Story. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-312-22730-2.

- ^ Sackville-West, Vita. Saint Joan of Arc, p. 21.

- ^ "The Glorious Age of the Dukes of Burgundy". Burgundy Today. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Sizer, Michael (2007). "The Calamity of Violence: Reading the Paris Massacres of 1418". Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, p. 167.

- ^ DeVries, p. 24.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, pp. 188–89.

- ^ DeVries, p. 24, 26.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, p. 10.

- ^ DeVries, p. 28.

- ^ Fraioli, Deborah Joan of Arc and the Hundred Years' War, Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005 p. 59.

- ^ Fraioli, Deborah Joan of Arc and the Hundred Years' War, Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005 pp. 59–60.

- ^ Jacques d'Arc (1380–1440) was a farmer at Domrémy who held the post of doyen – a local tax-collector and organizer of village defenses. He had married Isabelle de Vouthon (1387–1468), also called "Romée", in 1405. Their other children were Jacquemin, Jean, Pierre and Catherine. Charles VII ennobled Jacques and Isabelle's family on 29 December 1429, an act which was registered by the Chamber of Accounts on 20 January 1430. The grant permitted the family to change their surname to "du Lys".

- ^ "Chemainus Theatre Festival – The 2008 Season – Saint Joan – Joan of Arc Historical Timeline". Chemainustheatrefestival.ca. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ^ The French portion of the duchy, called the Barrois mouvant, was situated west of the Meuse River while the rest of the duchy (east of the Meuse) was a part of the Holy Roman Empire. The duchy of Bar was later incorporated into the province of Lorraine and the village of Domrémy renamed Domrémy-la-Pucelle, in honor of Joan of Arc. See Condemnation trial, p. 37.[1]. Retrieved 23 March 2006.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, p. 221.

- ^ Boyd, Beverly "Wyclif, Joan of Arc, and Margery Kempe" pp. 112–18 from Mystics Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue # 3 September 1986 p. 115.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses. p. 30.

- ^ Condemnation trial, pp. 58–59.[2]. Retrieved 23 March 2006.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 37–40.

- ^ a b Nullification trial testimony of Jean de Metz.[3]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses, p. 35.

- ^ Oliphant, ch. 2.[4]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Wagner, p. 348

- ^ Richey 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. "Joan of Arc By Herself And Her Witnesses", pp. 35–36.

- ^ Richey, Stephen W. (2000). "Joan of Arc: A Military Appreciation". The Saint Joan of Arc Center. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ This is the oldest known depiction of Joan of Arc, and the only one dating to her lifetime. It is drawn from the imagination based on accounts of her deeds at Orléans a few days before. "The earliest drawing of Joan of Arc that survives is a doodle in the margin of the parliamentary council register drawn by Clément de Fauquembergue. The entry is dated May 10, 1429. Joan is shown holding a banner and a sword, but she is wearing a dress and has long hair. Fauquembergue, drawing from his imagination, may be excused for putting her in women's clothing, but long after Joan's dressing practice was well known, many artists still preferred to dres her in skirts." Margaret Joan Maddox, "Jan of Arc" in: Matheson (ed.), Icons of the Middle Ages (2011), p. 442; see also Kelly DeVries, Joan of Arc: A Military Leader (2011), p. 29.

- ^ a b Vale, M.G.A., 'Charles VII', 1974, p. 55.

- ^ a b Vale, M.G.A., 'Charles VII', 1974, p. 56.

- ^ Historians often refer to this man by other names. Many call him "Count of Dunois" in reference to a title he received years after Joan's death, since this title is now his best-known designation. During Joan's lifetime he was often called "Bastard of Orléans" due to his condition as the illegitimate son of Louis of Orleans. His contemporaries viewed this "title" as nothing but a standard method of delineating such illegitimate offspring, but it nonetheless often confuses modern readers because "bastard" has become a popular insult. "Jean d'Orléans" is less precise but not anachronistic. For a short biography see Pernoud and Clin, pp. 180–81.

- ^ Lynch, Denis (1919). St. Joan of Arc: The Life-story of the Maid of Orleans. Benziger Brothers. p. 151.

joan of arc exclusion council.

- ^ Barrett, W.P. "The Trial of Jeanne d'Arc", p. 63.

- ^ Barrett, W.P. "The Trial of Jeanne d'Arc", p. 221.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. "Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses" pp. 63, 113.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, p. 230.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 74–83

- ^ "Orleans, Siege of | eHISTORY". ehistory.osu.edu. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ Fraioli, Deborah. "Joan of Arc, the Early Debate", pp. 87–88, 126–127.

- ^ a b c Boyd, Beverly "Wyclif, Joan of Arc, and Margery Kempe" pp. 112–118 from Mystics Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue # 3 September 1986 p. 116

- ^ DeVries, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Nullification trial testimony of Jean, Duke of Alençon.[5]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Lucie-Smith, pp. 156–160.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 122–126.

- ^ DeVries, p. 134.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc By Herself And Her Witnesses (1982), p. 137.

- ^ These range from mild associations of intrigue to scholarly invective. For an impassioned statement see Gower, ch. 4.[6] (Retrieved 12 February 2006) Milder examples are Pernoud and Clin, pp. 78–80; DeVries, p. 135; and Oliphant, ch. 6.[7]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Friedrich Henning (1904). The Maid of Orleans. A.C. McClurg. pp. 135–.

- ^ "Joan of Arc is burned at the stake for heresy". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, pp. 258–59.

- ^ Boyd, Beverly (September 1986). "Wyclif, Joan of Arc, and Margery Kempe". Mystics Quarterly. 12 (3): 112–18. JSTOR 20716744.

- ^ a b Geiger, Barbara (April 2008). "A Friend to Compiegne". Calliope Magazine. 18 (8): 32–34.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 161–70.

- ^ Payne, Andrew, "Joan of Arc, Jeanne la Pucelle, (1412 –1431)" (PDF), winchester-cathedral.org.uk, p. 2, retrieved 3 August 2019

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc: Her Story, p. 96.

- ^ "Joan of Arc, Saint". Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Library Edition, 12 September 2007 <http://www.library.eb.com/eb/article-27055>.

- ^ Régine Pernoud & Marie-Véronique Clin: Jeanne d'Arc, Fayard, Paris, 2 May 1986, p. 182.

- ^ Champion's description is included in Barrett's translation of the trial transcript: Barrett, W.P. The Trial of Joan of Arc, p. 390

- ^ Barrett, W.P. The Trial of Joan of Arc, p. 390.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. "Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses", pp. 165–67.

- ^ Judges' investigations 9 January – 26 March, ordinary trial 26 March – 24 May, recantation 24 May, relapse trial 28–29 May.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. "Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses", p. 269.

- ^ The retrial verdict later affirmed that Cauchon had no authority to try the case. See Joan of Arc: Her Story, by Régine Pernoud and Marie-Véronique Clin, p. 108.

- ^ Peters, Edward. Inquisition, p. 69.

- ^ Nullification trial testimony of Father Nicholas Bailly.[8]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Taylor, Craig, Joan of Arc: La Pucelle, p. 137.

- ^ Deposition of Nicholas de Houppeville on 8 May 1452 during Inquisitor Brehal's first investigation. See: Pernoud, Régine. "The Retrial of Joan of Arc; The Evidence at the Trial For Her Rehabilitation 1450–1456", p. 236.

- ^ See: Pernoud, Régine. "The Retrial of Joan of Arc; The Evidence at the Trial For Her Rehabilitation 1450–1456", p. 241.

- ^ Condemnation trial, p. 52.[9]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ a b Pernoud and Clin, p. 112. In the twentieth century George Bernard Shaw found this dialogue so compelling that sections of his play Saint Joan are literal translations of the trial record. See Shaw, "Saint Joan". Penguin Classics, Reissue edition (2001). ISBN 0-14-043791-6

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, p. 130.

- ^ Condemnation trial, pp. 314–16.[10]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Pernoud, p. 171.

- ^ Condemnation trial, pp. 342–343.[11]. Retrieved 12 February 2006. Also, in nullification trial testimony, Brother Pierre Migier stated, "As to the act of recantation, I know it was performed by her; it was in writing, and was about the length of a Pater Noster."[12] Retrieved 12 February 2006. In modern English this is better known as the Lord's Prayer, Latin and English texts available here:[13]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ a b Nullification trial testimony of Guillaume de Manchon.[14] Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ According to medieval clothing expert Adrien Harmand, she wore hose (chausses) attached to the doublet with 20 fastenings (aiguillettes) and perhaps wore outer boots (houseaux) for travel. "Jeanne d'Arc, son costume, son armure."[15](in French). Retrieved 23 March 2006.

- ^ See Pernoud, p. 220, which quotes appellate testimony by Friar Martin Ladvenu and Friar Isambart de la Pierre.

- ^ Nullification trial testimony of Jean Massieu.[16]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ "Summa Theologica", II – II, Q 169, Art. 2, ad. 3 [17]. Retrieved 8 January 2014

- ^ From "De Quadam Puella". For a discussion of this, see footnote 18 on p. 29 of "Joan of Arc: The Early Debate" (2000), by Deborah Fraioli.

- ^ Condemnation trial, p. 78.[18] (Retrieved 12 February 2006) Retrial testimony of Brother Séguin, (Frère Séguin, fils de Séguin), Professor of Theology at Poitiers, does not mention clothing directly, but constitutes a wholehearted endorsement of her piety.[19]. Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Fraioli, "Joan of Arc: The Early Debate", p. 131.

- ^ In February 2006 a team of forensic scientists began a six-month study to assess bone and skin remains from a museum at Chinon reputed to be those of the heroine. The study cannot provide a positive identification but could rule out some types of hoax through carbon dating and gender determination.[20] (Retrieved 1 March 2006) An interim report released 17 December 2006 states that this is unlikely to have belonged to her.[21]. Retrieved 17 December 2006.

- ^ Pernoud, p. 233.

- ^ DeVries, pp. 179–80.

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc By Herself And Her Witnesses (1982), p. 262.

- ^ "Joan of Arc, Declaration of Innocence : July 7th, 1456". archive.joan-of-arc.org. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Deuteronomy 22:5

- ^ Pernoud, Régine. Joan of Arc By Herself And Her Witnesses (1982), p. 268.

- ^ "The Spectator" The Outlook (3 July 1909) Vol. 92, pp. 548–50 Google Books 19 May 2016

- ^ Pope Benedict XV, Divina Disponente (Latin), 16 May 1920.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, pp. 247–64.

- ^ DeVries in "Fresh Verdicts on Joan of Arc", edited by Bonnie Wheeler, p. 3.

- ^ a b Richey, Stephen W. (2000). "Joan of Arc – A Military Appreciation".

- ^ English translation of Christine de Pizan's poem "The Tale of Joan of Arc" or Le Ditié de Jeanne d'Arc by L. Shopkow.[22] (Retrieved 12 February 2006) Analysis of the poem by Professors Kennedy and Varty of Magdalen College, Oxford. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Retrieved 12 February 2006. - ^ These tests, which her confessor describes as hymen investigations, are not reliable measures of virginity. However, they signified approval from matrons of the highest social rank at key moments of her life. Rehabilitation trial testimony of Jean Pasquerel.[23] Retrieved 12 March 2006.

- ^ Front National publicity logos include the tricolor flame and reproductions of statues depicting her. The graphics forums at Étapes magazine include a variety of political posters from the 2002 presidential election.[24] (in French) Retrieved 7 February 2006. Archived 29 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Loi instituant une fête nationale de Jeanne d'Arc, fête du patriotisme". fr:Journal officiel de la République française. 14 July 1920. p. 10018.

- ^ "Joan of Arc's answer song". The Library of Congress.

- ^ "Joan of Arc they are calling you".

- ^ Condemnation trial, pp. 36–37, 41–42, 48–49. Retrieved 1 September 2006.

- ^ In a parenthetical note to a military biography, DeVries asserts: "The visions, or their veracity, are not in themselves important for this study. What is important, in fact what is key to Joan's history as a military leader, is that she (author's emphasis) believed that they came from God," p. 35.

- ^ Many of these hypotheses were devised by people whose expertise is in history rather than medicine. For a sampling of papers that passed peer review in medical journals, see d'Orsi G., Tinuper P. (August 2006). ""I heard voices ...": from semiology, an historical review, and a new hypothesis on the presumed epilepsy of Joan of Arc". Epilepsy Behav. 9 (1): 152–57. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.04.020. PMID 16750938. S2CID 24961015. (idiopathic partial epilepsy with auditory features)

Foote-Smith E., Bayne L. (1991). "Joan of Arc". Epilepsia. 32 (6): 810–15. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1157.1991.tb05537.x. PMID 1743152. S2CID 221736116. (epilepsy)

Henker F. O. (December 1984). "Joan of Arc and DSM III". South. Med. J. 77 (12): 1488–90. doi:10.1097/00007611-198412000-00003. PMID 6390693. S2CID 44528365. (various psychiatric definitions)

Allen C (Autumn–Winter 1975). "The schizophrenia of Joan of Arc". Hist Med. 6 (3–4): 4–9. PMID 11630627. (schizophrenia) - ^ Though he did suggest the possibility of delusional disorder. Mackowiak, Philip; Post-Mortem: Solving History's Great Medical Mysteries, ACP Press, 2007

- ^ Hughes, J. R. (2005). "Did all those famous people really have epilepsy?". Epilepsy & Behavior. 6 (2): 115–39. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.11.011. PMID 15710295. S2CID 10436691.

- ^ Nores J. M., Yakovleff Y. (1995). "A historical case of disseminated chronic tuberculosis". Neuropsychobiology. 32 (2): 79–80. doi:10.1159/000119218. PMID 7477805.

- ^ Pernoud, p. 275.

- ^ Pernoud and Clin, pp. 3, 169, 183.

- ^ Nullification trial testimony of Dame Marguerite de Touroulde, widow of a king's counselor: "I heard from those that brought her to the king that at first they thought she was mad, and intended to put her away in some ditch, but while on the way they felt moved to do everything according to her good pleasure."[25] Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ Nullification trial testimony of Guillaume de Manchon.[26] Retrieved 12 February 2006.

- ^ "Tête casquée découverte en 1820 dans les démolitions des restes de l'ancienne église Saint-Eloi-Saint-Maurice, considérée parfois, mais à tort, comme représentant Jeanne d'Arc; c'est en réalité une tête de St Georges." Val de Loire; Maine, Orléanais, Touraine, Anjou, Hachette (1963), p. 70. See Edmunds, The Mission of Joan of Arc, (2008) 40ff for references to the defense given to the head's being an authentic likeness of Joan by Walter Scott and by Bernard Shaw.

- ^ Declan Butler (4 April 2007). "Joan of Arc's relics exposed as forgery". Nature. 446 (7136): 593. Bibcode:2007Natur.446..593B. doi:10.1038/446593a. PMID 17410145.

- ^ "Joan of Arc ring returns to France after auction sale". BBC. London. 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Dalya Alberge (27 December 2015). "Hot property: ring worn by Joan of Arc up for auction". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "Joan of Arc ring dating back to 15th century for sale at London auction". Ibtimes.co.uk. 27 December 2015. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ Joan of Arc ring stays in France after appeal to Queen, Kim Willsher, The Guardian, 26 August 2016

- ^ Brewer, E. Cobham (1900). Dictionary of Phrase and Fable (New ed.). Cassell and Company. p. 683.

- ^ Caze, Pierre (1819). La Vérité sur Jeanne d'Arc (in French). Paris.

- ^ Murray, Margaret (1921). The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. Oxford University Press. pp. 318–26.

- ^ Donald, Graeme (2009). Lies, Damned Lies, and History: A Catalogue of Historical Errors and Misunderstandings. The History Press. pp. 99–103. ISBN 978-0752452333.

See also

People who knew Joan of Arc

- Pierre d'Arc - Joan's brother who was captured with her at Compiegne

- Pierronne: Mystic who may have met Joan of Arc, and was burned at the stake for defending Joan's reputation

- Charles VII of France - Joan's King

- André de Lohéac: Lord of Lohéac, later Marshal of France, brother of Guy XIV de Laval, served in the army with Joan

- Gilles de Rais: Commander in the French Royal Army

- Guy XIV de Laval: Count of Laval, wrote a famous letter mentioning Joan and served in the army

- Jean II, Duke of Alençon: Commander in the French Royal army

- Jean de Dunois: Commander at Orleans, half-brother of the Duke of Orleans

- Jean V de Bueil: Count of Sancerre who served in the Royal army when Joan was there

- Marie of Anjou: Wife of Charles VII

- John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford: The English regent of occupied France

- Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick: English commander who was present at Joan's trial

- Philip III of Burgundy: The Duke of Burgundy, whose troops captured her at Compiegne

Other 15th century people associated with her

- Charles, Duke of Orléans - Duke of Orleans, whom Joan said was "greatly beloved by God"

- Christine de Pisan - Wrote a poem about her

Other women with a role in the Hundred Years War

- Joanna of Flanders: Countess who led an army earlier in the Hundred Years' War

- Jeanne de Clisson: Noblewoman who served as a privateer for Edward III to take revenge for the execution of her husband, Olivier de Clisson IV

- Jacqueline of Hainault: Countess who led the aristocratic faction in Holland in the 1420s.

- Margaret of Bavaria: Wife of Duke John the Fearless of Burgundy who was appointed by her husband to hold military command in his place

People compared to Joan of Arc

- Alena Arzamasskaia was a famed female rebel fighter in 17th-century Russia, sometimes called the Russian Joan of Arc

- Djamila Bouhired: FLN militant known as Algeria's Joan of Arc

- Farkhunda Malikzada: a 27-year-old Muslim woman who was publicly lynched by an angry mob in Kabul, Afghanistan

- Madeleine de Verchères: 17th-century New France colonist known as Canada's Joan of Arc

- María Pita and Agustina de Aragón: Spanish military heroines likened to Joan of Arc

- Ōhōri Tsuruhime: a Japanese female warrior (Onna-bugeisha) whose claim to divine inspiration has led to her being compared with Joan of Arc

- Niijima Yae: a Japanese female warrior who earned the nickname of the “Bakumatsu Joan of Arc”

Miscellaneous

- Jeanne d'Arc (Frémiet) - iconic gilded statue of her in Paris

- Equestrian statue of Joan of Arc (Portland, Oregon) - cast of the Frémiet statue

- Joan of Arc (Dubois) - another notable equestrian portrayal, with casts in Reims, Paris, Strasbourg and Washington, D.C.

- Equestrian statue of Joan of Arc (Washington, D.C.) - Washington, D.C. cast of the Dubois statue

- Joan of Arc (1948 film) - film about her starring Ingrid Bergman

- French corvette Jeanne d'Arc - French Navy corvette named after her, built in the late 1860s

- French cruiser Jeanne d'Arc (1899) - French armored cruiser named after her, built in 1899

- French cruiser Jeanne d'Arc (1930) - French cruiser named after her, built in 1930

- French cruiser Jeanne d'Arc (R97) - French helicopter cruiser named after her, built in 1961

- St. Joan of Arc Chapel - 15th century chapel in which she allegedly prayed

- Cross-dressing, gender identity, and sexuality of Joan of Arc

- André César Vermare: Sculpted a famous statue of Joan of Arc

- Joan of Arc, patron saint archive

References

- Pernoud, Régine (1982). Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses. translated by Edward Hyams. New York: Scarborough House. ISBN 978-0-8128-1260-2.

- DeVries, Kelly (1999). Joan of Arc: A Military Leader. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1805-3. OCLC 42957383.

- Famiglietti, Richard C. (1987). Royal Intrigue: Crisis at the Court of Charles VI 1392–1420. AMS studies in the Middle Ages, 9. New York: AMS Press. ISBN 978-0-404-61439-3.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1976). Joan of Arc. Bristol: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-0857-2.

- Oliphant, Mrs. (Margaret) (2003) [1896]. Jeanne d'Arc: Her Life and Death. Heroes of the Nations. IndyPublish.com. ISBN 978-1-4043-1086-5.

- Pernoud, Régine; Marie-Véronique Clin (1999). Joan of Arc: Her Story. translated and revised by Jeremy duQuesnay Adams; edited by Bonnie Wheeler. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-21442-5. OCLC 39890535.

- Wagner, John A (2006). Encyclopedia of the Hundred Years War. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32736-0.

- Bishop, Jacqueline. Joan of Arc. p. 2006.

- Lowell, Francis Cabot (1896). Joan of Arc. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Larkin, Sarah (1951). Joan of Arc. New York: Philosophical Library.

Further reading

Biographies

- Anon. The First Biography of Joan of Arc with the Chronicle Record of a Contemporary Account (PDF). trans. Rankin, Daniel & Quintal, Claire. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2011.

- Barrett, W.P., ed. (1932). The trial of Jeanne d'Arc. New York: Gotham house. OCLC 1314152.

- Brooks, Polly Schoyer (1999). Beyond the Myth: The Story of Joan of Arc. New York: Houghton Mifflin Co. ISBN 978-0-397-32422-4. OCLC 20319268.

- Castor, Helen (2014). Joan of Arc: A History. London: Faber and Faber. p. 328. ISBN 9780571284627.

- de Quincey, Thomas (August 2004). The English Mail-Coach and Joan of Arc.

- France, Anatole (7 October 2006). The Life of Joan of Arc., 19th century French classic

- Gower, Ronald Sutherland (24 October 2005). Joan of Arc.

- Kaiser, Anton (2017). Joan of Arc: A Study in Charismatic Women's Leadership. US: Black Hills Books. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-945333-08-8.

- Meltzer, Francoise (2001). For Fear of the Fire: Joan of Arc and the Limits of Subjectivity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-51982-1. OCLC 46240234.

- Pernoud, Régine (1955). The Retrial of Joan of Arc; The Evidence at the Trial For Her Rehabilitation 1450–1456. trans. J.M. Cohen. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. OCLC 1338471.

- Pernoud, Régine (1994). Joan of Arc By Herself and Her Witnesses. trans. E. Hymans. London: Scarborough House. ISBN 978-0-8128-1260-2. OCLC 31535658.

- Pernoud, Régine; Clin, Marie-Véronique (1999). Joan of Arc: Her Story. trans. Jeremy Duquesnay Adams. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-22730-2. OCLC 39890535.

- Richey, Stephen W. (2003). Joan of Arc: The Warrior Saint. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-98103-7. OCLC 52030963.

- Spoto, Donald (2007). Joan : the mysterious life of a heretic who became a saint. San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 978-0-06-081517-2. OCLC 84655969.

Historiography and memory

- Fraioli, Deborah (2002). Joan of Arc: The Early Debate. London: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-880-8. OCLC 48680250.

- Heimann, Nora (2005). Joan of Arc in French Art and Culture (1700–1855): From Satire to Sanctity. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-5085-0.

- Heimann, Nora; Coyle, Laura (2006). Joan of Arc: Her Image in France and America. Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art in association with D Giles Limited. ISBN 978-1-904832-19-5.

- Russell, Preston (2005). Lights of Madness: In Search of Joan of Arc. Savannah, GA: Frederic C. Beil, Pub. ISBN 978-1-929490-24-0.

- Tumblety, Joan. "Contested histories: Jeanne d'Arc and the front national." The European Legacy (1999) 4#1 pp: 8–25.

In French

- Quicherat, Jules-Étienne-Joseph, ed. (1965) [1841–1849]. Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d'Arc dite la Pucelle. Publiés pour la première fois d'après les manuscrits de la Bibliothèque nationale, suivis de tous les documents historiques qu'on a pu réunir et accompagnés de notes et d'éclaircissements (in French). Vol. 1–5. New York: Johnson. OCLC 728420.

- Contamine, Philippe (1994). De Jeanne d'Arc aux guerres d'Italie: figures, images et problèmes du XVe siècle (in French). Orleans: Paradigme. ISBN 2-86878-109-8.

- Beaune, Colette (2004). Jeanne d'Arc (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-01705-0.

- Michaud-Fréjaville, Françoise (2005). Une ville, une destinée : Orléans et Jeanne d'Arc (in French). Orleans, Paris: Honoré Champion.

- Neveux, François (2012). De l'hérétique à la sainte. Les procès de Jeanne d'Arc revisités (in French). Caen: Presses universitaires de Caen. ISBN 978-2-84133-421-6.

- Contamine, Philippe; Bouzy, Olivier; Hélary, Xavier (2012). Jeanne d'Arc. Histoire et dictionnaire (in French). Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 978-2-221-10929-8.

- Guyon, Catherine; Delavenne, Magali (2013). De Domrémy... à Tokyo: Jeanne d'Arc et la Lorraine (in French). Nancy: Presses universitaires de Nancy. ISBN 978-2-8143-0154-2.

- Bouzy, Olivier (2013). Jeanne d'Arc en son siècle (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-67205-2.

- Boudet, Jean-Patrice; Hélary, Xavier (2014). Jeanne d'Arc: histoire et mythes (in French). Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 978-2-7535-3389-9.

- Krumeich, Gerd (2017). Jeanne d'Arc à travers l'histoire (in French). Paris: Belin. ISBN 978-2-410-00096-2.

Related history

- Allmand, C. (1988). The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c. 1300–1450. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31923-2.

- Davis, H.W.C (August 2004). Medieval Europe.

- Guizot, François Pierre Guillaume (April 2004). A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times. Vol. 3.

- Haaren, John Henry; Poland, A.B. Famous Men of the Middle Ages.

- Lacroix, Paul (February 2004). Manners, Custom and Dress During the Middle Ages and During the Renaissance Period.

- Lingard, John. The History of England.

- Perroy, Edouard (1965). The Hundred Years War. trans. W.B. Wells. New York: Capricorn Books.

- Pollard, A.F. (August 2004). The History of England: A Study in Political Evolution.

- Power, Eileen Edna (9 August 2004). Medieval People.

- Vauchez, André (1997). Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages. trans. Jean Birrell. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44559-7.

External links

- Joan of Arc Archive – Online collection of Joan of Arc-related materials, including biographies and translations.

- "Blessed Joan of Arc" (written before her canonization) – Catholic Encyclopedia entry from the 1919 edition.

- Catholic Online Saints – short biography from Catholic Online Saints.

- Joan of Arc's Companions-in-arms – English version of page about soldiers who served alongside Joan of Arc.

- Joan of Arc Museum – Website for a museum in Rouen, France located near the place she was executed.

- INRAP page on Orleans' fortifications: Article on the archaeological excavation of a portion of Orleans' fortifications dating from the siege in 1428–1429.

- Location of Joan of Arc's Execution – Google Maps satellite map of the square in Rouen and monument marking the site of her execution.

- Locations in Joan of Arc's campaigns and life – Google Maps feature showing locations from her birth until her death.

- Catholic Saints page about Joan of Arc – Brief biography and hagiographic information from Catholic Saints.

- The Real Joan of Arc: Who Was She? – Long analysis of various issues and controversies, from 1000 Questions.

- Literature by and about Joan of Arc in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Joan of Arc in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- International Jeanne d'Arc Centre (in French, English, and German)

- "Jeanne d'Arc" in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints

- Historical Association for Joan of Arc Studies – Research work and study reports (in English and German)

- Protocol of the 1431st process and the Rehabilitation process

- Jeanne d'Arc la pucelle cinematography (in English)

- Films about Jeanne d'Arc, International Joan of Arc Society (with film clips)

- filmrezension.de: Dossier on Jeanne d'Arc films from 1928 to the present

- Centre Jeanne d'Arc at the Orleans Municipal Library (French)

- "The Siege of Orleans", BBC Radio 4 discussion with Anne Curry, Malcolm Vale & Matthew Bennett (In Our Time, 24 May 2007)

- Finding aid to the Acton Griscom collection of Jeanne d'Arc manuscripts at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

- Joan of Arc

- 1431 deaths

- 15th-century Christian mystics

- 15th-century Christian saints

- 15th-century French women

- 15th-century Roman Catholic martyrs

- Angelic visionaries

- Armagnac faction

- Beatifications by Pope Pius X

- Canonizations by Pope Benedict XV

- Christian female saints of the Middle Ages

- Executed French women

- Executed people from Lorraine

- Female wartime cross-dressers

- French prisoners of war in the Hundred Years' War

- French Roman Catholic saints

- History of Catholicism in France

- History of Rouen

- Medieval French saints

- Michael (archangel)

- Overturned convictions in France

- Patron saints of France

- People executed by the Kingdom of England by burning

- People executed for heresy

- People executed under the Lancastrians

- People from Vosges (department)

- Prophets in Christianity

- Roman Catholic mystics

- Women in 15th-century warfare

- Women in medieval European warfare

- Women in war in France

- Women mystics

- Wrongful executions