Maribor

Maribor | |

|---|---|

City and Municipality | |

Center of Maribor | |

|

Flag of Maribor Flag Coat of arms of Maribor Coat of arms | |

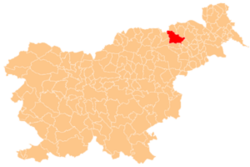

Location of the Municipality of Maribor in Slovenia | |

| Country | |

| Municipality | Maribor |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Franc Kangler |

| Area | |

| • City and Municipality | 147.5 km2 (57.0 sq mi) |

| Population (2009-06-30)[1] | |

| • City and Municipality | 112,642 |

| • Density | 760/km2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 210,000 |

| Time zone | UTC+01 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02 (CEST) |

| Post code | 2000 |

| Area code | 02 |

| Website | www |

| Source: Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, census of 2002. | |

Maribor () (German: [Marburg an der Drau] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is the second largest city in Slovenia with 106,308 inhabitants as of 2008.[2] Maribor lies on the river Drava at the meeting point of the Pohorje mountain, the Drava Valley, the Drava Plain, and the Kozjak and Slovenske gorice hill ranges. Maribor's coat of arms features a white dove flying downwards above a white castle with two towers and a portcullis on a red shield.

Maribor is also the seat of the Municipality of Maribor, which has 119,071 inhabitants as of 2007 [3], and the center of the Slovenian region of Lower Styria and its largest city. Maribor Airport is the second largest international airport in Slovenia.

History

In 1164 a castle known as the Marchburch (Middle High German for "March Castle") was documented in Styria. It was first built on Piramida Hill, just above the city. Maribor was first mentioned as a market near the castle in 1204, and received town privileges in 1254. It began to grow rapidly after the victory of Rudolf I of Habsburg over Otakar II of Bohemia in 1278. Maribor withstood sieges by Matthias Corvinus in 1480 and 1481 and by the Ottoman Empire in 1532 and 1683, and the city remained under the control of the Habsburg Monarchy until 1918. Maribor, previously in the Catholic Diocese of Graz-Seckau, became part of the Diocese of Lavant on 1 June 1859, and the seat of its Prince-Bishop. The name of the diocese (the name of a river in Carinthia flowing into the Drava at the Slovenian village of Dravograd) was changed to the Diocese of Maribor on 5 March 1962. It was elevated to an archdiocese by Pope Benedict XVI on 7 April 2006.

Before the First World War, the city had a population of 80% Austrian Germans and 20% Slovenes, and most of the city's capital and public life was in Austrian German control. Therefore, it was mainly known by its Austrian name [Marburg an der Drau] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). According to the last Austro-Hungarian census in 1910, Maribor and the suburbs Studenci (Brunndorf), Pobrežje (Pobersch), Tezno (Thesen), Radvanje (Rothwein), Krčevina (Kartschowin), and Košaki (Leitersberg) were composed of 31,995 Austrian Germans (including Jews) and 6,151 ethnic Slovenes. The wider surrounding area was populated almost exclusively by Slovenes, although many Austrian Germans lived in smaller towns like Ptuj.

During World War I, many Slovenes in Carinthia and Styria were detained for allegedly being enemies of the Austrian Empire, which led to further conflicts between Austrian Germans and Slovenes. After the collapse of Austria-Hungary, Maribor was claimed by both the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and by German Austria. On 1 November 1918, a meeting was held by Colonel Anton Holik in Melje's barracks, where it was determined the city would be part of German Austria. Ethnic Slovene major Rudolf Maister, who was present at the meeting, renounced the decision. He was awarded the rank of General[4] by the National Council for (Slovenian) Styria on the same day and organized Slovenian military units in Maribor to successfully take control of the city. All Austrian soldiers and officers were demobilized and sent home to new German Austria. The city council held a secret meeting where a decision was taken to do whatever possible to gain Maribor for German Austria. They organized a military unit, the so-called Green Guard (Schutzwehr). The approximately 400 well-armed soldiers of this ethnic German-Austrian unit threatened pro-Slovenian and pro-Yugoslav major Maister, leading the Slovenian troops to disarm them in the early morning of 23 November. Thereafter there was no real threat to the authority of Maister in the city.

On 27 January 1919, Austrian Germans awaiting the United States peace delegation at the city's marketplace were taken under fire by Slovenian troops which feared this crowd of thousands of ethnic German citizens. Nine people were killed and more than eighteen were seriously wounded;[5] who was responsible for the shooting has not been conclusively established. German sources accused Maister's troops of shooting without cause, while Slovene witnesses, such as Dr. Maks Pohar, claimed that the Austrian Germans attacked Slovenian soldiers guarding the Maribor city hall. Anyway, the killed Austrian Germans had been unarmed.[citation needed] German language media called the incident Marburg's Bloody Sunday.

Since Maribor was firmly in the hands of the Slovenian forces and encircled with completely Slovenian territory, it was recognized as part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes without a plebiscite in the Treaty of Saint-Germain of September 1919 between the victors of WWI and German Austria.

After 1918, many of Maribor's Austrian Germans emigrated from the Kingdom of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs into Austria, especially German-speaking officials who did not originate from the region. Austrian German schools, clubs, and organisations were closed in the new state of Yugoslavia, although ethnic Germans still made up more than 25% of the city's total population in the 1930s. A policy of cultural assimilation was pursued in Yugoslavia against the Austrian German minority similar to the Germanization policy of Austria against its Slovene minority in Carinthia. However, in the late 1930s this policy was abandoned and the Austrian German minority's position improved significantly in order to gain better diplomatic relations with Nazi Germany.

In 1941, Lower Styria, the Yugoslav part of Styria, was annexed by Nazi Germany. German troops marched into the town around 9pm, on April 8, 1941.

On April 26, Adolf Hitler, who encouraged his followers to "make this land German again," visited Maribor where a grand reception was organized by local Germans in the city castle. Immediately after the occupation, Nazi Germany began mass expulsions of Slovenes to the Independent State of Croatia, Serbia, and later on to the concentration and work camps in Germany. The Nazi goal was to exterminate[citation needed] or Germanize the Slovene population of Lower Styria after the war.[citation needed] Many patriots were taken hostages and later shot in the prisons of Maribor and Graz. This led to organized partisans resistance.[citation needed] The city, a major industrial center with extensive armaments industry, was systematically bombed by the Allies in the last years of World War II. Many local Germans were involved in crimes against local Slovenes;[citation needed] the remaining German population, except those that actively collaborated with the resistance during the war, was summarily expelled after the end of the war in 1945.

After the liberation, Maribor capitalized on its proximity to Austria as well as its skilled workforce, and developed into a major transit and cultural center of Northern Slovenia and the biggest industrial city in Yugoslavia,[citation needed] – enabled by Tito's decision not to build an Iron Curtain at the borders towards Austria and Italy and to provide passports to the citizens.

When Slovenia seceded from Yugoslavia in 1991, the loss of the Yugoslav market severely strained the city's economy which was based on heavy industry, resulting in record levels of unemployment of almost 25%. The situation has improved since the mid-1990s with the development of small and medium sized businesses and industry. So now Maribor has overcome the industry crisis and is looking forward to shinier days. Slovenia entered the European Union in 2004, introduced the Euro currency in 2007 and joined the Schengen treaty; accordingly all border controls between Slovenia and Austria ceased at Christmas of 2007.

Unemployment was 11.5% (ILO: 7.8%) in June 2007.

Jewish community

The Jews of Maribor were first mentioned in 1277 when they allegedly already lived in Jewish quarter of the city, however, the first reliable source dates back to 1317. The Jewish ghetto was located in the south-eastern part of the city and it comprised, at it's peak, several main streets in the city centre as well as part of the main city square. The ghetto boasted a synagogue, a Jewish cemetery and also a Talmudic school. The Jewish community of Maribor was numerically most significant around the year 1410. After 1450, the circumstances changed dramatically: increasing competition that coincided with an economiccrisis dealt a severe blow to economic activities that were crucial to their economic success. According to the decree issued by Emperor Maximilian I in 1496, Jews were forced to leave. Restrictions on settlement and business for Jews remained until 1861.[6]

Well known rabbi Israel Isserlein who was the chief Rabbi of Carinthia, Styria and Carniola, spent most of his life as a resident of Maribor.

Maribor synagogue is one of the oldest preserved synagogues in Europe, and one of two only left in Slovenia.[7]

Contemporary Maribor

Popular tourist sites in Maribor include the 12th century cathedral in the Gothic style and the town hall constructed in the Renaissance fashion. The castle dates from the 15th century.

The city hosts the University of Maribor, established in 1975,[8] and many other schools. It is also home to the oldest grapevine in the world, called Stara trta,[9] which is more than 400 years old.

Maribor is hometown of NK Maribor,[10] a Slovenian football team. They participated in the UEFA Champions League in the 1999-2000 season.

Every January, the skiing centre of Mariborsko Pohorje,[11] situated on the outskirts of the city on the slopes of the Pohorje mountain range, hosts women's slalom and giant slalom races for the Alpine Skiing World Cup known as Zlata lisica (The Golden Fox). Every June, the two-week Festival Lent[12] (named after the waterfront district called Lent) is held, with hundreds of musical, theatrical and other events.

Maribor was named as an Alpine city in 2000 and chosen as European Capital of Culture 2012 alongside with Guimarães, Portugal. Maribor will be the host city of the 2013 Winter Universiade.

Demography

Population Development[13]

| 1991 | 1996 | 2002 | 2004 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 119.828 | 116.147 | 110.668 | 112.558 | 119.071 |

City Districts

The city districts (Slovene: mestne četrti)

The city of Maribor has 12 districst as listed below, but the whole Municipality of Maribor also includes Kamnica, Pekre, Limbuš, Razvanje, Malečnik-Ruperče and Brestrenica-Gaj. The river Drava divides the districts Center, Koroška Vrata, Melje and Ivan Cankar from the other districts of the city. They are all very good connected with 4 traffic bridges, 1 train bridge and 1 pedestrian bridge.

| No. | District |

|---|---|

| 1. | Center |

| 2. | Koroška vrata |

| 3. | Melje |

| 4. | Ivan Cankar |

| 5. | Magdalena |

| 6. | Tabor |

| 7. | Studenci |

| 8. | Pobrežje |

| 9. | Nova Vas |

| 10. | Tezno |

| 11. | Brezje - Dogoše - Zrkovci |

| 12. | Radvanje |

Climate

| Climate data for Maribor | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Source: http://www.arso.gov.si/vreme/napovedi%20in%20podatki/podneb_10_tabele.html | |||||||||||||

Famous natives and residents

List of notable individuals who were born or lived in Maribor:

- Tomaž Barada, taekwondoist

- Sani Bečirovič, basketball player

- Fredi Bobic, German-Slovene football player

- Andrej Brvar, poet

- Aleš Čeh, football player

- Lev Detela, writer, poet, and translator

- Mladen Dolar, philosopher

- Vekoslav Grmič, Roman Catholic bishop and theologian

- Herta Haas, second wife of Joseph Broz Tito

- Polona Hercog, tennis player

- Israel Isserlin, Medieval rabbi

- Archduke Johann of Austria, Habsburg nobleman and philanthropist

- Drago Jančar, author

- Janko Kastelic, conductor and music director

- Matjaž Kek, football player and coach

- Ottokar Kernstock, Austrian poet

- Aleksander Knavs, football player

- Edvard Kocbek, poet, essayist, and politician

- Katja Koren, alpine skier

- Anton Korošec, politician

- Bratko Kreft, author

- Rene Krhin, football player

- Rudolf Maister, military leader

- Janez Menart, poet and translator

- Guiseppe Morpurgo, Founder of Generali

- Tomaž Pandur, stage director

- Tone Partljič, playwright, screenwriter, politician

- Žarko Petan, writer, essayist, theatre and film director

- Janko Pleterski, historian

- Miran Potrč, politician

- Zoran Predin, singer

- Ladislaus von Rabcewicz, Austrian civil engineer

- Stanko Majcen, playwright

- Zorko Simčič, writer and essayist

- Anton Martin Slomšek, Roman Catholic bishop, author, poet, and advocate of Slovene culture.

- Leon Štukelj, Olympic champion

- Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, Austrian admiral

- Anton Trstenjak, theologian, psychologist, essayist

- Danilo Türk, president of Slovenia

- Saša Vujačić, NBA basketball player

- Prežihov Voranc,writer and political activist

- Zlatko Zahovič, football player

Picture gallery

-

City Hall

-

Maribor castle

-

Panorama of Lent (The oldest part of Maribor)

-

University of Maribor

-

Cathedral

-

Slovene National Theatre in snow

-

Soccer stadium

-

Tito's road

-

New highrise buildings

-

New Year in Maribor

-

View from the cathedral, down to Slomšek square

-

Panoramic view of Maribor from Pohorje

-

Rudolf Maister

-

An old church on the Kalvarija hill in Maribor

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Maribor is twinned with:

References

- Notes

- ^ Statistical Office of the Republic of Slovenia, census of 2002

- ^ [1]

- ^ Maribor Municipality site

- ^ Maister's rank of General was recognized by the Ministry of Defence of the National Government of SHS on 14 December 1918; published in Official Journal No. 1.

- ^ The German Wikipedia gives the figures of 13 killed and more than 60 wounded.

- ^ Jewish community of Slovenia

- ^ Maribor Synagogue

- ^ University of Maribor site.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Official website of NK Maribor

- ^ Official website of Mariborsko Pohorje

- ^ Festival Lent website

- ^ [3]

- ^ "Twin Towns - Graz Online - English Version". www.graz.at. Retrieved 2010-01-05.