Mary of Teck

| Mary of Teck | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Formal portrait from the 1920s | |||||

| Queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions; Empress consort of India | |||||

| Tenure | 6 May 1910 – 20 January 1936 | ||||

| Coronation | 22 June 1911 | ||||

| Imperial Durbar | 12 December 1911 | ||||

| Born | 26 May 1867 Kensington Palace, London | ||||

| Died | 24 March 1953 (aged 85) Marlborough House, London | ||||

| Burial | 31 March 1953 | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| House | Teck / Cambridge | ||||

| Father | Francis, Duke of Teck | ||||

| Mother | Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge | ||||

Mary of Teck (Victoria Mary Augusta Louise Olga Pauline Claudine Agnes; 26 May 1867 – 24 March 1953) was Queen consort of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions and Empress of India as the wife of King George V.

Although technically a princess of Teck, in the Kingdom of Württemberg, she was born and raised in England. Her parents were Francis, Duke of Teck, who was of German extraction, and Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, who was a granddaughter of King George III. She was informally known as "May", after her birth month.

At the age of 24, she was betrothed to Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, the eldest son of the Prince of Wales, but six weeks after the announcement of the engagement, he died unexpectedly of pneumonia. The following year, she became engaged to Albert Victor's next surviving brother, George, who subsequently became king. Before her husband's accession, she was successively Duchess of York, Duchess of Cornwall, and Princess of Wales.

As queen consort from 1910, she supported her husband through the First World War, his ill health and major political changes arising from the aftermath of the war. After George's death in 1936, she became queen mother when her eldest son, Edward VIII, ascended the throne, but to her dismay, he abdicated later the same year in order to marry twice-divorced American socialite Wallis Simpson. She supported her second son, George VI, until his death in 1952. She died the following year, during the reign of her granddaughter Elizabeth II, who had not yet been crowned.

Early life

| Teck-Cambridge Family |

|---|

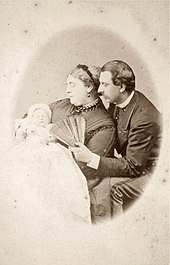

Princess Victoria Mary ("May") of Teck was born on 26 May 1867 at Kensington Palace, London. May's father was Prince Francis, Duke of Teck, the son of Duke Alexander of Württemberg by his morganatic wife, Countess Claudine Rhédey von Kis-Rhéde (created Countess von Hohenstein in the Austrian Empire).

May's mother was Princess Mary Adelaide of Cambridge, the third child and younger daughter of Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, and Princess Augusta of Hesse-Kassel. She was baptised in the Chapel Royal of Kensington Palace on 27 July 1867 by Charles Thomas Longley, Archbishop of Canterbury.[2] Before she became queen, she was known to her family, friends and the public by the diminutive name of "May", after her birth month.[3]

May's upbringing was "merry but fairly strict".[4] She was the eldest of four children, the only girl, and "learned to exercise her native discretion, firmness, and tact" by resolving her three younger brothers' petty boyhood squabbles.[5] They played with their cousins, the children of the Prince of Wales, who were similar in age.[6]

May was educated at home by her mother and governess (as were her brothers until they were sent to boarding schools).[7] The Duchess of Teck spent an unusually long time with her children for a lady of her time and class,[4] and enlisted May in various charitable endeavours, which included visiting the tenements of the poor.[8]

Although her mother was a grandchild of King George III, May was only a minor member of the British royal family. Her father, the Duke of Teck, had no inheritance or wealth and carried the lower royal style of Serene Highness because his parents' marriage was morganatic.[9] However, the Duchess of Teck was granted a parliamentary annuity of £5,000 and received about £4,000 a year from her mother, the Duchess of Cambridge.[10] Despite this, the family was deeply in debt and lived abroad from 1883, in order to economise.[11] The Tecks travelled throughout Europe, visiting their various relations. They stayed in Florence, Italy, for a time, where May enjoyed visiting the art galleries, churches, and museums.[12]

In 1885, the Tecks returned to London, and took up residence at White Lodge, in Richmond Park. May was close to her mother, and acted as an unofficial secretary, helping to organise parties and social events. She was also close to her aunt, the Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, and wrote to her every week. During the First World War, the Crown Princess of Sweden helped pass letters from May to her aunt, who lived in enemy territory in Germany until her death in 1916.[13]

Engagements

In December 1891, May was engaged to her second cousin once removed, Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale, the eldest son of the Prince of Wales.[14] The choice of May as bride for the Duke owed much to Queen Victoria's fondness for her, as well as to her strong character and sense of duty. However, Albert Victor died six weeks later, in a recurrence of the worldwide 1889–90 influenza pandemic.[15]

Albert Victor's brother, Prince George, Duke of York, now second in line to the throne, evidently became close to May during their shared period of mourning, and Queen Victoria still favoured May as a suitable candidate to marry a future king.[16] In May 1893, George proposed, and May accepted. They were soon deeply in love, and their marriage was a success. George wrote to May every day they were apart and, unlike his father, never took a mistress.[17]

Duchess of York (1893–1901)

May married Prince George, Duke of York, in London on 6 July 1893 at the Chapel Royal, St James's Palace.[18] The new Duke and Duchess of York lived in York Cottage on the Sandringham Estate in Norfolk, and in apartments in St James's Palace. York Cottage was a modest house for royalty, but it was a favourite of George, who liked a relatively simple life.[19] They had six children: Edward, Albert, Mary, Henry, George, and John.

The children were put into the care of a nanny, as was usual in upper-class families at the time. The first nanny was dismissed for insolence and the second for abusing the children. This second woman, anxious to suggest that the children preferred her to anyone else, would pinch Edward and Albert whenever they were about to be presented to their parents so that they would start crying and be speedily returned to her. On discovery, she was replaced by her effective and much-loved assistant, Charlotte Bill.[20]

Sometimes, Mary and George appear to have been distant parents. At first, they failed to notice the nanny's abuse of the young Princes Edward and Albert,[21] and their youngest son, Prince John, was housed in a private farm on the Sandringham Estate, in Bill's care, perhaps to hide his epilepsy from the public. However, despite Mary's austere public image and her strait-laced private life, Mary was a caring mother in many respects, revealing a fun-loving and frivolous side to her children and teaching them history and music.

Edward wrote fondly of his mother in his memoirs: "Her soft voice, her cultivated mind, the cosy room overflowing with personal treasures were all inseparable ingredients of the happiness associated with this last hour of a child's day ... Such was my mother's pride in her children that everything that happened to each one was of the utmost importance to her. With the birth of each new child, Mama started an album in which she painstakingly recorded each progressive stage of our childhood".[22] He expressed a less charitable view, however, in private letters to his wife after his mother's death: "My sadness was mixed with incredulity that any mother could have been so hard and cruel towards her eldest son for so many years and yet so demanding at the end without relenting a scrap. I'm afraid the fluids in her veins have always been as icy cold as they are now in death."[23]

As Duke and Duchess of York, George and May carried out a variety of public duties. In 1897, she became the patron of the London Needlework Guild in succession to her mother. The guild, initially established as The London Guild in 1882, was renamed several times and was named after May between 1914 and 2010.[24] Samples of her own embroidery range from chair seats to tea cosies.[25]

On 22 January 1901, Queen Victoria died, and May's father-in-law ascended the throne. For most of the rest of that year, George and May were known as the "Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York". For eight months they toured the British Empire, visiting Gibraltar, Malta, Egypt, Ceylon, Singapore, Australia, New Zealand, Mauritius, South Africa and Canada. No royal had undertaken such an ambitious tour before. She broke down in tears at the thought of leaving her children, who were to be left in the care of their grandparents, for such a long time.[26]

Princess of Wales (1901–1910)

On 9 November 1901, nine days after arriving back in Britain and on the King's sixtieth birthday, George was created Prince of Wales. The family moved their London residence from St James's Palace to Marlborough House. As Princess of Wales, May accompanied her husband on trips to Austria-Hungary and Württemberg in 1904. The following year, she gave birth to her last child, John. It was a difficult labour, and although she recovered quickly, her newborn son suffered respiratory problems.[27]

From October 1905 the Prince and Princess of Wales undertook another eight-month tour, this time of India, and the children were once again left in the care of their grandparents.[28] They passed through Egypt both ways and on the way back stopped in Greece. The tour was almost immediately followed by a trip to Spain for the wedding of King Alfonso XIII to Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg, at which the bride and groom narrowly avoided assassination.[29] Only a week after returning to Britain, May and George went to Norway for the coronation of George's brother-in-law and sister, King Haakon VII and Queen Maud.[30]

Queen consort (1910–1936)

On 6 May 1910, Edward VII died. Mary's husband ascended the throne and she became queen consort. When her husband asked her to drop one of her two official names, Victoria Mary, she chose to be called Mary, preferring not to be known by the same style as her husband's grandmother, Queen Victoria.[31] Queen Mary was crowned with the King on 22 June 1911 at Westminster Abbey. Later in the year, the new King and Queen travelled to India for the Delhi Durbar held on 12 December 1911, and toured the sub-continent as Emperor and Empress of India, returning to Britain in February.[32]

The beginning of Mary's period as consort brought her into conflict with her mother-in-law, Queen Alexandra. Although the two were on friendly terms, Alexandra could be stubborn; she demanded precedence over Mary at the funeral of Edward VII, was slow in leaving Buckingham Palace, and kept some of the royal jewels that should have been passed to the new queen.[33]

During the First World War, Queen Mary instituted an austerity drive at the palace, where she rationed food, and visited wounded and dying servicemen in hospital, which caused her great emotional strain.[34] After three years of war against Germany, and with anti-German feeling in Britain running high, the Russian Imperial Family, which had been deposed by a revolutionary government, was refused asylum, possibly in part because the Tsar's wife was German-born.[35] News of the Tsar's abdication provided a boost to those in Britain who wished to replace their own monarchy with a republic.[36] The war ended in 1918 with the defeat of Germany and the abdication and exile of the Kaiser.

Two months after the end of the war, Queen Mary's youngest son, John, died at the age of thirteen. She described her shock and sorrow in her diary and letters, extracts of which were published after her death: "our poor darling little Johnnie had passed away suddenly ... The first break in the family circle is hard to bear but people have been so kind & sympathetic & this has helped us [the King and me] much."[37]

Her staunch support of her husband continued during the latter half of his reign. She advised him on speeches and used her extensive knowledge of history and royalty to advise him on matters affecting his position. He appreciated her discretion, intelligence, and judgement.[38] She maintained an air of self-assured calm throughout all her public engagements in the years after the war, a period marked by civil unrest over social conditions, Irish independence, and Indian nationalism.[39]

In the late 1920s, George V became increasingly ill with lung problems, exacerbated by his heavy smoking. Queen Mary paid particular attention to his care. During his illness in 1928, one of his doctors, Sir Farquhar Buzzard, was asked who had saved the King's life. He replied, "The Queen".[40] In 1935, King George V and Queen Mary celebrated their silver jubilee, with celebrations taking place throughout the British Empire. In his jubilee speech, George paid public tribute to his wife, having told his speechwriter, "Put that paragraph at the very end. I cannot trust myself to speak of the Queen when I think of all I owe her."[41]

Queen mother (1936–1952)

George V died on 20 January 1936, after his physician, Lord Dawson of Penn, gave him an injection of morphine and cocaine that may have hastened his death.[42] Queen Mary's eldest son ascended the throne as Edward VIII. She was now the queen mother, though she did not use that style, and was instead known as Her Majesty Queen Mary.

Within the year, Edward caused a constitutional crisis by announcing his desire to marry his twice-divorced American mistress, Wallis Simpson. Mary disapproved of divorce, which was against the teaching of the Anglican church, and thought Simpson wholly unsuitable to be the wife of a king. After receiving advice from the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Stanley Baldwin, as well as the Dominion governments, that he could not remain king and marry Simpson, Edward abdicated.

Though loyal and supportive of her son, Mary could not comprehend why Edward would neglect his royal duties in favour of his personal feelings.[43] Simpson had been presented formally to both King George V and Queen Mary at court,[44] but Mary later refused to meet her either in public or privately.[45] She saw it as her duty to provide moral support for her second son, the reserved and stammering Prince Albert, Duke of York, who ascended the throne on Edward's abdication, taking the name George VI. When Mary attended the coronation, she became the first British dowager queen to do so.[46] Edward's abdication did not lessen her love for him, but she never wavered in her disapproval of his actions.[17][47]

Mary took an interest in the upbringing of her granddaughters, Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret, and took them on various excursions in London, to art galleries and museums. (The princesses' own parents thought it unnecessary for them to be taxed with any demanding educational regime.)[48]

During the Second World War, George VI wished his mother to be evacuated from London. Although she was reluctant, she decided to live at Badminton House, Gloucestershire, with her niece, Mary Somerset, Duchess of Beaufort, the daughter of her brother Lord Cambridge.[49] Her personal belongings were transported from London in seventy pieces of luggage. Her household, which comprised fifty-five servants, occupied most of the house, except for the Duke and Duchess's private suites, until after the war. The only people to complain about the arrangements were the royal servants, who found the house too small,[50] though Queen Mary annoyed her niece by having the ancient ivy torn from the walls as she considered it unattractive and a hazard. From Badminton, in support of the war effort, she visited troops and factories and directed the gathering of scrap materials. She was known to offer lifts to soldiers she spotted on the roads.[51] In 1942, her youngest surviving son, Prince George, Duke of Kent, was killed in an air crash while on active service. Mary finally returned to Marlborough House in June 1945, after the war in Europe had resulted in the defeat of Nazi Germany.

Mary was an eager collector of objects and pictures with a royal connection.[52] She paid above-market estimates when purchasing jewels from the estate of Dowager Empress Marie of Russia[53] and paid almost three times the estimate when buying the family's Cambridge Emeralds from Lady Kilmorey, the mistress of her late brother Prince Francis.[54] In 1924, the famous architect Sir Edwin Lutyens created Queen Mary's Dolls' House for her collection of miniature pieces.[55] Indeed, she has sometimes been criticised for her aggressive acquisition of objets d'art for the Royal Collection. On several occasions, she would express to hosts, or others, that she admired something they had in their possession, in the expectation that the owner would be willing to donate it.[56] Her extensive knowledge of, and research into, the Royal Collection helped in identifying artefacts and artwork that had gone astray over the years.[57] The royal family had lent out many objects over previous generations. Once she had identified unreturned items through old inventories, she would write to the holders, requesting that they be returned.[58]

Death

In 1952, King George VI died, the third of Queen Mary's children to predecease her; her eldest granddaughter, Princess Elizabeth, ascended the throne as Queen Elizabeth II. The death of a third child profoundly affected her. Mary remarked to Princess Marie Louise: "I have lost three sons through death, but I have never been privileged to be there to say a last farewell to them."[60]

Mary died on 24 March 1953 in her sleep at the age of 85, ten weeks before her granddaughter's coronation.[61] Mary let it be known that, in the event of her death, the coronation was not to be postponed. Her remains lay in state at Westminster Hall, where large numbers of mourners filed past her coffin. She is buried beside her husband in the nave of St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[62]

Legacy

Sir Henry "Chips" Channon wrote that she was "above politics ... magnificent, humorous, worldly, in fact nearly sublime, though cold and hard. But what a grand Queen."[63]

The ocean liner RMS Queen Mary;[64] the Royal Navy battlecruiser, HMS Queen Mary, which was destroyed at the Battle of Jutland in 1916; Queen Mary University of London;[65] Queen Mary Reservoir in Surrey, United Kingdom;[66] Queen Mary College, Lahore;[67] Queen Mary's Hospital, Roehampton, London; Queen Mary Hospital, Hong Kong; Queen Mary's Peak, the highest mountain in Tristan da Cunha; Queen Mary Land in Antarctica; and Queen Mary's College in Chennai, India, are named in her honour.

Actresses who have portrayed Queen Mary include Dame Wendy Hiller (on the London stage in Crown Matrimonial),[68] Greer Garson (in the television production of Crown Matrimonial), Judy Loe (in Edward the Seventh), Dame Flora Robson (in A King's Story), Dame Peggy Ashcroft (in Edward & Mrs. Simpson), Phyllis Calvert (in The Woman He Loved), Gaye Brown (in All the King's Men), Miranda Richardson (in The Lost Prince), Margaret Tyzack (in Wallis & Edward), Claire Bloom (in The King's Speech), Judy Parfitt (in W.E.), Valerie Dane (in Downton Abbey), and Dame Eileen Atkins (in Bertie and Elizabeth and The Crown).

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

- 26 May 1867 – 6 July 1893: Her Serene Highness Princess Victoria Mary of Teck

- 6 July 1893 – 22 January 1901: Her Royal Highness The Duchess of York

- 22 January 1901 – 9 November 1901: Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall and York

- 9 November 1901 – 6 May 1910: Her Royal Highness The Princess of Wales

- 6 May 1910 – 20 January 1936: Her Majesty The Queen

- 20 January 1936 – 24 March 1953: Her Majesty Queen Mary

Honours

Arms

Queen Mary's arms were the royal coat of arms of the United Kingdom impaled with her family arms – the arms of her grandfather, Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, in the 1st and 4th quarters, and the arms of her father, Prince Francis, Duke of Teck, in the 2nd and 3rd quarters.[69][70] The shield is surmounted by the imperial crown, and supported by the crowned lion of England and "a stag Proper" as in the arms of Württemberg.[70]

Issue

| Name | Birth | Death | Spouse | Children |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edward VIII Later Duke of Windsor |

23 June 1894 | 28 May 1972 | Wallis Simpson | None |

| George VI | 14 December 1895 | 6 February 1952 | Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon | Elizabeth II Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon |

| Mary, Princess Royal | 25 April 1897 | 28 March 1965 | Henry Lascelles, 6th Earl of Harewood | George Lascelles, 7th Earl of Harewood The Honourable Gerald Lascelles |

| Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester | 31 March 1900 | 10 June 1974 | Lady Alice Montagu Douglas Scott | Prince William of Gloucester Prince Richard, Duke of Gloucester |

| Prince George, Duke of Kent | 20 December 1902 | 25 August 1942 | Princess Marina of Greece and Denmark | Prince Edward, Duke of Kent Princess Alexandra, The Honourable Lady Ogilvy Prince Michael of Kent |

| Prince John | 12 July 1905 | 18 January 1919 | Never married | None |

Ancestry

See also

- Crown of Queen Mary

- King George and Queen Mary, BBC documentary

Notes

- ^ The Times (London), Monday, 29 July 1867 p. 12 col. E

- ^ Her three godparents were Queen Victoria, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII and May's future father-in-law), and Princess Augusta, Duchess of Cambridge.[1]

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 24

- ^ a b Pope-Hennessy, p. 66

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 45

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 55

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 68, 76, 123

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 68

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 36–37

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 114

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 112

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 133

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 503–505

- ^ May's maternal grandfather, Prince Adolphus, Duke of Cambridge, was a brother of Prince Edward Augustus, Duke of Kent, who was the father of Queen Victoria, Albert Victor's paternal grandmother.

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 201

- ^ Edwards, p. 61

- ^ a b Prochaska, Frank (January 2008) [September 2004], "Mary (1867–1953)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34914, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Her bridesmaids were the Princesses Maud and Victoria of Wales, Victoria Melita, Alexandra and Beatrice of Edinburgh, Helena Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein, Margaret and Patricia of Connaught and Strathearn, and Alice and Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg.

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 291

- ^ Wheeler-Bennett, pp. 16–17

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 393

- ^ Windsor, pp. 24–25

- ^ Ziegler, p. 538

- ^ Queen Mother's Clothing Guild official website, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ e.g. Mary, Queen of England (1943), Chair seat, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Queen Mary (1909), Tea cosy, Springhill, County Londonderry: National Trust

- ^ Edwards, p. 115

- ^ Edwards, pp. 142–143

- ^ Edwards, p. 146

- ^ The driver of their coach and over a dozen spectators were killed by a bomb thrown by an anarchist, Mateo Morral.

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 407

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 421

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 452–463

- ^ Edwards, pp. 182–193

- ^ Edwards, pp. 244–245

- ^ Edwards, p. 258

- ^ Edwards, p. 262

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 511

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 549

- ^ Edwards, p. 311

- ^ Gore, p. 243

- ^ The Times (London), Wednesday, 25 March 1953 p. 5

- ^ Watson, Francis (1986), "The Death of George V", History Today, 36: 21–30

- ^ Airlie, p. 200

- ^ Windsor, p. 255

- ^ Windsor, p. 334

- ^ According to custom, crowned heads do not attend coronations of other kings and queens. Pope-Hennessy, p. 584

- ^ Edwards, p. 401 and Pope-Hennessy, p. 575

- ^ Edwards, p. 349

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 596

- ^ Mosley, Charles, ed. (2003), "Duke of Beaufort, 'Seat' section", Burke's Peerage & Gentry, 107th edition, vol. I p. 308

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 600

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 412

- ^ Clarke, William (1995), The Lost Fortune of the Tsars

- ^ Thomson, Mark (29 August 2005), Document – A Right Royal Affair, BBC Radio 4

See also Kilmorey Papers (D/2638) (pdf), Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. - ^ Pope-Hennessy, pp. 531–534

- ^ Rose, p. 284

- ^ Pope-Hennessy, p. 414

- ^ Windsor, p. 238

- ^ "Queen Mary laid to rest in Windsor", BBC On This Day: 31 March 1953; retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Marie Louise, p. 238

- ^ "1953: Queen Mary dies peacefully after illness". BBC. Retrieved 29 May 2018.

- ^ Royal Burials in the Chapel by location, St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle, archived from the original on 22 January 2010, retrieved 1 May 2010

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Channon, Sir Henry (1967), Chips: The Diaries of Sir Henry Channon, Edited by Robert Rhodes James, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, p. 473

- ^ RMS Queen Mary 2 was named after the original ocean liner, and is only indirectly named after the Queen.

- ^ Moss, G. P.; Saville, M. V. (1985), From Palace to College – An illustrated account of Queen Mary College, University of London, pp. 57–62, ISBN 0-902238-06-X

- ^ History of the Queen Mary Reservoir- Sunbury Matters, Village Matters, retrieved 25 April 2014

{{citation}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Introduction, Queen Mary College, Lahore, retrieved 29 October 2014

- ^ "Dame Wendy Hiller", The Guardian, 16 May 2003, retrieved 1 May 2010

- ^ Maclagan, Michael; Louda, Jiří (1999), Line of Succession: Heraldry of the Royal Families of Europe, London: Little, Brown & Co, pp. 30–31, ISBN 1-85605-469-1

- ^ a b Pinches, John Harvey; Pinches, Rosemary (1974), The Royal Heraldry of England, Heraldry Today, Slough, Buckinghamshire: Hollen Street Press, p. 267, ISBN 0-900455-25-X

- ^ a b c d e "The Ancestry of the Princess May", Bow Bells: A magazine of general literature and art for family reading, 23 (288), London: 31, 7 July 1893

References

- Airlie, Mabell (1962), Thatched with Gold, London: Hutchinson

- Edwards, Anne (1984), Matriarch: Queen Mary and the House of Windsor, Hodder and Stoughton, ISBN 0-340-24465-8

- Gore, John (1941), King George V: A Personal Memoir, London: John Murray

- Marie Louise, Princess (1959), My Memories of Six Reigns, Penguin Books

- Pope-Hennessy, James (1959), Queen Mary, London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

- Prochaska, Frank (January 2008) [September 2004], "Mary (1867–1953)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/34914, retrieved 1 May 2010

- Rose, Kenneth (1983), King George V, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-78245-2

- Wheeler-Bennett, Sir John (1958), King George VI, London: Macmillan

- Windsor, HRH The Duke of (1951), A King's Story, London: Cassell and Co

- Ziegler, Philip (1990), King Edward VIII, London: Collins, ISBN 0-00-215741-1

External links

- Mary of Teck

- 1867 births

- 1953 deaths

- 19th-century British people

- 20th-century British people

- 19th-century British women

- 20th-century British women

- British royal consorts

- Queen mothers

- Indian empresses

- Princesses of Wales

- British princesses by marriage

- Duchesses of York

- Duchesses of Rothesay

- Companions of the Order of the Crown of India

- Dames of the Order of Queen Maria Luisa

- Dames Grand Cross of the Order of St John

- Dames Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire

- Dames Grand Cross of the Royal Victorian Order

- Double dames

- Grand Crosses of the Order of the Queen of Sheba

- German princesses

- Teck-Cambridge family

- Knights Grand Commander of the Order of the Star of India

- Ladies of the Garter

- Ladies of the Royal Order of Victoria and Albert

- Members of the Royal Red Cross

- Recipients of the Royal Victorian Chain

- People associated with Queen Mary University of London

- The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada

- Women of the Victorian era

- Burials at St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle

- Dames of the Order of Louise

- Dames of the Order of Saint Isabel

- Recipients of the Order of the Star of Ethiopia