Matthew the Apostle

Matthew the Apostle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Levi[1] |

| Died | near Hierapolis or Ethiopia, relics in Salerno, Italy |

| Residence | Capernaum[1] |

| Parents | Alphaeus (father)[1] |

Matthew the Apostle (Template:Lang-he Mattityahu or Template:Hebrew Mattay, "Gift of YHVH"; Template:Lang-el Matthaios; also known as Saint Matthew and as Levi) was, according to the Christian Bible, one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and, according to Christian tradition, one of the four Evangelists.

In the New Testament

Among the early followers and apostles of Jesus, Matthew is mentioned in Matthew 9:9 and Matthew 10:3 as a publican who, while sitting at the "receipt of custom" in Capernaum, was called to follow Jesus.[2] Matthew may have collected taxes from the Hebrew people for Herod Antipas.[3][4][5] Matthew is also listed among the twelve, but without identification of his background, in Mark 3:18, Luke 6:15 and Acts 1:13. In passages parallel to Matthew 9:9, both Mark 2:14 and Luke 5:27 describe Jesus' calling of the tax collector Levi, the son of Alphaeus, but Mark and Luke never explicitly equate this Levi with the Matthew named as one of the twelve apostles.

Early life

Matthew was a 1st-century Galilean (presumably born in Galilee, which was not part of Judea or the Roman Iudaea province), the son of Alpheus.[6] As a tax collector he would have been literate in Aramaic and Greek.[3][5][7][8] His fellow Jews would have despised him for what was seen as collaborating with the Roman occupation force.[9]

After his call, Matthew invited Jesus home for a feast. On seeing this, the Scribes and the Pharisees criticized Jesus for eating with tax collectors and sinners. This prompted Jesus to answer, "I came not to call the righteous, but sinners to repentance." (Mark 2:17, Luke 5:32)

Ministry

The New Testament records that as a disciple, he followed Jesus, and was one of the witnesses of the Resurrection and the Ascension of Jesus. Afterwards, the disciples withdrew to an upper room (Acts 1:10–14)[10] (traditionally the Cenacle) in Jerusalem.[6] The disciples remained in and about Jerusalem and proclaimed that Jesus was the promised Messiah.

In the Babylonian Talmud (Sanhedrin 43a) "Mattai" is one of five disciples of "Jeshu".[11]

Later Church fathers such as Irenaeus (Against Heresies 3.1.1) and Clement of Alexandria claim that Matthew preached the Gospel to the Jewish community in Judea, before going to other countries. Ancient writers are not agreed as to what these other countries are.[6] The Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church each hold the tradition that Matthew died as a martyr,[12][13] although this was rejected by the gnostic heretic Heracleon as early as the second century.[5]

Matthew's Gospel

The Gospel of Matthew is anonymous: the author is not named within the text, and the superscription "according to Matthew" was added some time in the second century.[14][15] The tradition that the author was the disciple Matthew begins with the early Christian bishop Papias of Hierapolis (c. 100–140 CE), who is cited by the Church historian Eusebius (260–340 CE), as follows: "Matthew collected the oracles (logia: sayings of or about Jesus) in the Hebrew language ( Hebraïdi dialektōi), and each one interpreted (hērmēneusen – perhaps "translated") them as best he could."[16][Notes 1]

On the surface, this has been taken to imply that Matthew's Gospel itself was written in Hebrew or Aramaic by the apostle Matthew and later translated into Greek, but nowhere does the author claim to have been an eyewitness to events, and Matthew's Greek "reveals none of the telltale marks of a translation".[17][14] Scholars have put forward several theories to explain Papias: perhaps Matthew wrote two gospels, one, now lost, in Hebrew, the other our Greek version; or perhaps the logia was a collection of sayings rather than the gospel; or by dialektōi Papias may have meant that Matthew wrote in the Jewish style rather than in the Hebrew language.[16] The consensus is that Papias does not describe the Gospel of Matthew as we know it, and it is generally accepted that Matthew was written in Greek, not in Aramaic or Hebrew.[18]

Non-canonical or Apocryphal Gospels

In the 3rd-century Jewish–Christian gospels attributed to Matthew were used by Jewish–Christian groups such as the Nazarenes and Ebionites. Fragments of these gospels survive in quotations by Jerome, Epiphanius and others. Most academic study follows the distinction of Gospel of the Nazarenes (26 fragments), Gospel of the Ebionites (7 fragments), and Gospel of the Hebrews (7 fragments) found in Schneemelcher's New Testament Apocrypha. Critical commentators generally regard these texts as having been composed in Greek and related to Greek Matthew.[19] A minority of commentators consider them to be fragments of a lost Aramaic or Hebrew language original.

The Infancy Gospel of Matthew is a 7th-century compilation of three other texts: the Protevangelium of James, the Flight into Egypt, and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas.

Origen said the first Gospel was written by Matthew.[20] This Gospel was composed in Hebrew near Jerusalem for Hebrew Christians and translated into Greek, but the Greek copy was lost. The Hebrew original was kept at the Library of Caesarea. The Nazarene Community transcribed a copy for Jerome[21] which he used in his work.[22] Matthew's Gospel was called the Gospel according to the Hebrews[23] or sometimes the Gospel of the Apostles[24] and it was once believed that it was the original to the Greek Matthew found in the Bible.[25] However, this has been challenged by modern biblical scholars such as Bart Ehrman and James R. Edwards.[26][27][28]

Jerome relates that Matthew was supposed by the Nazarenes to have composed their Gospel of the Hebrews[29] though Irenaeus and Epiphanius of Salamis consider this simply a revised version canonical Gospel. This Gospel has been partially preserved in the writings of the Church Fathers, said to have been written by Matthew.[27] Epiphanius does not make his own the claim about a Gospel of the Hebrews written by Matthew, a claim that he merely attributes to the heretical Ebionites.[28]

Veneration

Saint Matthew the Apostle | |

|---|---|

| Apostle, Evangelist, Martyr | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Lutheran Church Oriental Orthodoxy Protestant Churches Roman Catholic Church Anglicanism |

| Major shrine | Salerno, Italy |

| Feast | 21 September (Western Christianity) 22nd October (Coptic Orthodox) 16 November (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | Angel |

| Patronage | Accountants; Salerno, Italy; bankers; tax collectors; perfumers; civil servants[30] |

Matthew is recognized as a saint in the Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Lutheran[31] and Anglican churches. (See St. Matthew's Church.) His feast day is celebrated on 21 September in the West and 16 November in the East. (For those churches which follow the traditional Julian Calendar, 16 November currently falls on 29 November of the modern Gregorian Calendar). He is also commemorated by the Orthodox, together with the other Apostles, on 30 June (13 July), the Synaxis of the Holy Apostles. His tomb is located in the crypt of Salerno Cathedral in southern Italy.

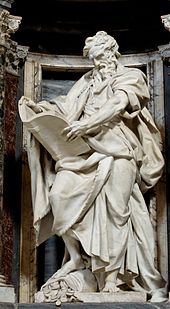

Like the other evangelists, Matthew is often depicted in Christian art with one of the four living creatures of Revelation 4:7. The one that accompanies him is in the form of a winged man. The three paintings of Matthew by Caravaggio in the church of San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome, where he is depicted as called by Christ from his profession as gatherer, are among the landmarks of Western art.

In Islam

The Quran speaks of Jesus' disciples but does not mention their names, instead referring to them as "helpers to the work of God".[32] Muslim exegesis and Qur'an commentary, however, name them and include Matthew amongst the disciples.[33] Muslim exegesis preserves the tradition that Matthew, with Andrew, were the two disciples who went to Ethiopia (not the African country, but a region called 'Ethiopia' south of the Caspian Sea) to preach the message of God.

Gallery

-

Base of a pillar at Sacred Heart Church, Puducherry, India

-

Stained glass depiction of Saint Matthew at St. Matthew's German Evangelical Lutheran Church in Charleston, South Carolina

-

A terracotta sculptural model, Giuseppe Bernardi

-

The Crypt at Salerno Cathedral

See also

Notes

- ^ Eusebius, "History of the Church" 3.39.14–17, c. 325 CE, Greek text 16: "ταῦτα μὲν οὖν ἱστόρηται τῷ Παπίᾳ περὶ τοῦ Μάρκου· περὶ δὲ τοῦ Ματθαῖου ταῦτ’ εἴρηται· Ματθαῖος μὲν οὖν Ἑβραΐδι διαλέκτῳ τὰ λόγια συνετάξατο, ἡρμήνευσεν δ’ αὐτὰ ὡς ἧν δυνατὸς ἕκαστος. Various English translations published, standard reference translation by Philip Schaff at CCEL: "[C]oncerning Matthew he [Papias] writes as follows: 'So then(963) Matthew wrote the oracles in the Hebrew language, and every one interpreted them as he was able.'(964)" Online version includes footnotes 963 and 964 by Schaff.

Irenaeus of Lyons (died c. 202 CE) makes a similar comment, possibly also drawing on Papias, in his Against Heresies, Book III, Chapter 1, "Matthew also issued a written Gospel among the Hebrews in their own dialect" (see Dwight Jeffrey Bingham (1998), Irenaeus' Use of Matthew's Gospel in Adversus Haereses, Peeters, p. 64 ff).

References

- ^ a b c Easton, Matthew George (1897). . Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

- ^ Matthew 9:9 Mark 2:15–17 Luke 5:29

- ^ a b Werner G. Marx, Money Matters in Matthew, Bibliotheca Sacra 136:542 (April–June 1979):148- 57

- ^ "Encyclopædia Britannica: Saint Matthew the Evangelist". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2013-09-03.

- ^ a b c James Orr, ed. (1915). "The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: Matthew". Studylight.org. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ a b c Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Catherine Hezser (2001), Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine, Mohr Siebeck, p. 172, ISBN 978-3161475467, retrieved 2014-09-10,

Even if they were pious and able to read the Hebrew Bible and/or literate in Greek poetry and prose, the writing they had to do in every day life ... 24 For the evidence of tax receipts amongst the Judaean Desert papyri see section II.

- The Cambridge history of Judaism: 2 p192 ed. William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein "We are now touching upon that milieu in which Greek language and civilization were readily accepted in order to ... A great number of tax receipts on ostraca mainly from the 2nd century BCE show how Jews, Egyptians and Greeks.. "

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Encyclopædia Britannica: Saint Matthew the Evangelist". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ^ "Saint Matthew". 21 September 2016.

- ^ Anchor Bible Reference Library, Doubleday, 2001 pp. 130-133, 201

- ^ Wilhelm Schneemelcher New Testament Apocrypha: Writings Relating to the Apostles revised edition translated R. McL. Wilson – 2003 Page 17 "in the Babylonian Talmud five disciples of Jesus are mentioned by name: 'Matthai, Nagai, Nezer, Buni, Thoda' (Sanhedrin 43a)."

- ^ "Eusebius, Church History 3.24.6", The Works of Nathaniel Lardner, Volume 5, W. Ball, p. 299, 1838, retrieved 2010-02-22

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Darrell L. Bock – Studying the Historical Jesus: A Guide to Sources and Methods – Page 164 2002 "The early church tradition is consistent in claiming that Matthew wrote his Gospel in Hebrew for the Jews (Irenaeus, Against Heresies 3.1.1)."

- ^ a b Harrington 1991, p. 8.

- ^ Nolland 2005, p. 16.

- ^ a b Turner 2008, p. 15–16.

- ^ Hagner 1986, p. 281.

- ^ Ehrman 1999, p. 43.

- ^ Vielhauer NTA1

- ^ Edwards, James R. (2009). The Hebrew Gospel and the Development of the Synoptic Tradition. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0802862341.

- Repschinski, Boris (1998). The Controversy Stories in the Gospel of Matthew:... Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 14. ISBN 978-3525538739.

- ^ Edward Williams B. Nicholson, ed. (1979). The Gospel according to the Hebrews, its fragments tr. and annotated, with a critical analysis of the evidence relating to it, by E. B. Nicholson. [With] Corrections and suppl. notes. p. 82.

- ^ Saint Jerome (2000). Thomas P. Halton (ed.). On Illustrious Men (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 100). CUA Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0813201009.

- ^ Arland J. Hultgren; Steven A. Haggmark (1996). The Earliest Christian Heretics: Readings from Their Opponents. Fortress Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0800629632.

- ^ Edward Williams B. Nicholson, ed. (1979). The Gospel according to the Hebrews, its fragments tr. and annotated, with a critical analysis of the evidence relating to it, by E. B. Nicholson. [With] Corrections and suppl. notes. p. 26.

- John Bovee Dods (1858). Gibson Smith (ed.). The Gospel of Jesus. G. Smith. p. iv.

- ^ Harrison, Everett Falconer (1964). Introduction to the New Testament. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 9780802847867.

- ^ Edwards, James R. The Hebrew Gospel & the Development of the Synoptic Tradition, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2009. ISBN 978-0802862341, pp 245-258

- Ehrman, Bart, Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0199839438, p. 43

- See also the two-source hypothesis

- ^ a b Watson E. Mills, Richard F. Wilson and Roger Aubrey Bullard, Mercer Commentary on the New Testament, Mercer University Press, ISBN 978-0865548640, 2003, p.942

- ^ a b Saint Epiphanius (Bishop of Constantia in Cyprus) (1987). Frank Williams (ed.). The Panarion of Ephiphanius of Salamis: Book I (sects 1-46). BRILL. p. 129. ISBN 9789004079267.

What they call a Gospel according to Matthew, though it is not entirely complete, but is corrupt and mutilated — and they call this thing 'Hebrew'!

- ^ "On Illustrious Men (The Fathers of the Church, Volume 100)".

- ^ "Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle, Washington, D.C". Stmatthewscathedral.org. 2013-09-21. Retrieved 2014-07-10.

- ^ Evangelical Lutheran Church in America: Lesser Festivals, Commemorations, and Occasions, Evangelical Lutheran Worship, page 57. Augsburg Fortress.

- ^ Quran 3:49–53

- ^ Historical Dictionary of Prophets In Islam And Judaism, Brandon M. Wheeler, Disciples of Christ: "Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon"

Bibliography

Commentaries

- Allison, D. C. (2004). Matthew: A Shorter Commentary. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08249-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, W. D.; Allison, D. C. (2004). Matthew 1–7. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08355-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, W. D.; Allison, D. C. (1991). Matthew 8–18. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08365-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Davies, W. D.; Allison, D. C. (1997). Matthew 19–28. T&T Clark. ISBN 978-0-567-08375-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duling, Dennis C. (2010). "The Gospel of Matthew". In Aune, David E. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0825-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - France, R. T. (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8028-2501-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 9780814658031Template:Inconsistent citations

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Keener, Craig S. (1999). A commentary on the Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3821-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luz, Ulrich (1992). Matthew 1–7: a commentary. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-9600-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luz, Ulrich (2001). Matthew 8–20: a commentary. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-6034-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luz, Ulrich (2005). Matthew 21–28: a commentary. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0-8006-3770-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Leon (1992). The Gospel according to Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-85111-338-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nolland, John (2005). The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Eerdmans. ISBN 0802823890.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Turner, David L. (2008). Matthew. Baker. ISBN 978-0-8010-2684-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

General works

- Aune, David E. (ed.) (2001). The Gospel of Matthew in current study. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4673-0.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Aune, David E. (1987). The New Testament in its literary environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25018-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Beaton, Richard C. (2005). "How Matthew Writes". In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83285-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Browning, W. R. F. (2004). Oxford Dictionary of the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860890-5.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00720-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian's Account of His Life and Teaching. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-64517-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clarke, Howard W. (2003). The Gospel of Matthew and Its Readers. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34235-5.

- Cross, Frank L.; Livingstone, Elizabeth A., eds. (2005) [1997]. "Matthew, Gospel acc. to St.". The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (3 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1064. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dunn, James D. G. (2003). Jesus Remembered. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3931-2.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512474-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ehrman, Bart D. (2012). Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-220460-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fuller, Reginald H. (2001). "Biblical Theology". In Metzger, Bruce M.; Coogan, Michael D. (eds.). The Oxford Guide to Ideas & Issues of the Bible. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hagner, D. A. (1986). "Matthew, Gospel According to". In Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Vol. 3: K-P. Wm. B. Eerdmans. pp. 280–8. ISBN 978-0-8028-8163-2.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: External link in|chapterurl=|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Harris, Stephen L. (1985). Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kowalczyk, A. (2008). The influence of typology and texts of the Old Testament on the redaction of Matthew’s Gospel. Bernardinum. ISBN 978-83-7380-625-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kupp, David D. (1996). Matthew's Emmanuel: Divine Presence and God's People in the First Gospel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57007-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levine, Amy-Jill (2001). "Visions of kingdoms: From Pompey to the first Jewish revolt". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513937-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Levison, J.; Pope-Levison, P. (2009). "Christology". In Dyrness, William A.; Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (eds.). Global Dictionary of Theology. InterVarsity Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Luz, Ulrich (2005). Studies in Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3964-0.

- Luz, Ulrich (1995). The Theology of the Gospel of Matthew. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43576-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McMahon, Christopher (2008). "Introduction to the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles". In Ruff, Jerry (ed.). Understanding the Bible: A Guide to Reading the Scriptures. Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Leon (1986). New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-45571-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Peppard, Michael (2011). The Son of God in the Roman World: Divine Sonship in Its Social and Political Context. Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Perkins, Pheme (1998-07-28). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". The Cambridge Companion to Biblical Interpretation. ISBN 0521485932.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in Kee, Howard Clark, ed. (1997). The Cambridge companion to the bible: part 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48593-7.{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Saldarini, Anthony (2003). "Matthew". Eerdmans commentary on the Bible. ISBN 0802837115.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William (2003). Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0. - Saldarini, Anthony (1994). Matthew's Christian-Jewish Community. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-73421-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sanford, Christopher B. (2005). Matthew: Christian Rabbi. Author House.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scholtz, Donald (2009). Jesus in the Gospels and Acts: Introducing the New Testament. Saint Mary's Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Senior, Donald (2001). "Directions in Matthean Studies". The Gospel of Matthew in Current Study: Studies in Memory of William G. Thompson, S.J. ISBN 0802846734.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in Aune, David E. (ed.) (2001). The Gospel of Matthew in current study. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4673-0.{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Senior, Donald (1996). What are they saying about Matthew?. PaulistPress. ISBN 978-0-8091-3624-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanton, Graham (1993). A gospel for a new people: studies in Matthew. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25499-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Strecker, Georg (2000) [1996]. Theology of the New Testament. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-0-664-22336-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tuckett, Christopher Mark (2001). Christology and the New Testament: Jesus and His Earliest Followers. Westminster John Knox Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Van de Sandt, H. W. M. (2005). "Introduction". Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish–Christian Milieu?. ISBN 9023240774.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in Van de Sandt, H. W. M., ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Weren, Wim (2005). "The History and Social Setting of the Matthean Community". Matthew and the Didache: Two Documents from the Same Jewish–Christian Milieu?. ISBN 9023240774.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help), in Van de Sandt, H. W. M., ed. (2005). Matthew and the Didache. Royal Van Gorcum&Fortress Press. ISBN 978-90-232-4077-8.{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- St Matthew the Apostle from The Golden Legend

- Apostle and Evangelist Matthew Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- Benedict XVI, "Matthew", General audience, 30 August 2006

Life of Jesus: Ministry Events | ||

Hometown Rejection of Jesus, "Physician, heal thyself" |

Events |

Followed by New Wine into Old Wineskins |