Megaregions of the United States

| Population tables of U.S. cities |

|---|

|

| Cities |

| Urban areas |

| Populous cities and metropolitan areas |

| Metropolitan areas |

| Megaregions |

|

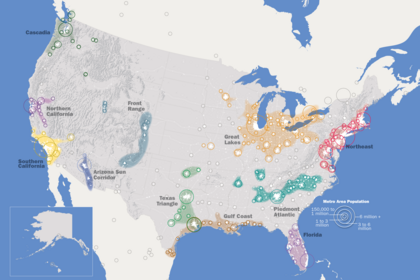

Megaregions of the United States are clustered networks of US-American cities, the population of which currently ranges or is projected to range from about 57 to 63 million by the year 2025.[1][2][3]

America 2050,[4] a project of the Regional Plan Association, lists 11 megaregions in the United States, Canada and Mexico.[1] Megapolitan areas were explored in a July 2005 report by Robert E. Lang and Dawn Dhavale of the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech.[5] A later 2007 article by Lang and Nelson uses 20 megapolitan areas grouped into 10 megaregions.[6] The concept is based on the original megalopolis model.[3]

Definition

A megaregion is a large network of metropolitan regions that share several or all of the following:

- Environmental systems and topography

- Infrastructure systems

- Economic linkages

- Settlement and land use patterns

- Culture and history[7]

A megaregion may also be known as a megalopolis or megapolitan area. More than 70 percent of the nation's population and jobs are located in 11 megaregions identified by the Regional Plan Association (RPA), which is an independent, non-profit New York-based planning organization. Megaregions are becoming the new competitive units in the global economy, characterized by the increasing movement of goods, people and capital among their metropolitan regions.[7] "The New Megas," asserted Richard Florida (2006), "are the real economic organizing units of the world, producing the bulk of its wealth, attracting a large share of its talent and generating the lion's share of innovation."[8]

The megaregion concept provides cities and metropolitan regions a context within which to cooperate across jurisdictional borders, including the coordination of policies, to address specific challenges experienced at the megaregion scale, such as planning for high-speed rail, protecting large watersheds, and coordinating regional economic development strategies.

The American-based Regional Plan Association recognizes 11 emerging megaregions:[9]

- Arizona Sun Corridor Megaregion (extends into Mexico)

- Cascadia Megaregion (Pacific Northwest; shared with Canada)[10]

- The RPA definition of this region includes the Boise metropolitan area in Idaho. That state is included in some definitions of the Pacific Northwest, but the Boise area is removed by hundreds of miles from any other area included in the RPA's definition of "Cascadia".

- Florida Megaregion

- The megaregion does not cover the entire state. The Panhandle and several mostly rural counties to its east are not included; the Pensacola and Fort Walton Beach areas in the far west of the Panhandle are instead included in the Gulf Coast Megaregion (below).

- Front Range Megaregion

- The RPA definition of this region extends well to the south of the Colorado–Wyoming area typically called the Front Range Urban Corridor, following the Interstate 25 corridor into New Mexico and incorporating Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The RPA definition also includes the geographically detached Wasatch Front of Utah.

- Great Lakes Megaregion

- This megalopolis extends into Canada, whose geographers take a more inclusive approach than the American RPA when defining the Canadian section of the region.

- Gulf Coast Megaregion

- The RPA definition of this region includes the entirety of two metropolitan areas that straddle the U.S.–Mexico border, specifically Matamoros–Brownsville and Reynosa–McAllen.

- Northeast Megaregion

- Northern California Megaregion

- Piedmont Atlantic Megaregion[11]

- Southern California Megaregion

- The RPA definition includes the Las Vegas Valley, as well as the Tijuana area in Mexico.

- Texas Triangle Megaregion

- The RPA definition includes the geographically detached Oklahoma City–Tulsa Metropolitan Corridor in Oklahoma.

Identification

The Regional Plan Association methodology for identifying the emerging megaregions included assigning each county a point for each of the following:

- It was part of a core-based statistical area;

- Its population density exceeded 200 people per square mile as of the 2000 census;

- The projected population growth rate was expected to be greater than 15 percent and total increased population was expected to exceed 1,000 people by 2025;

- The population density was expected to increase by 50 or more people per square mile between 2000 and 2025; and

- The projected employment growth rate was expected to be greater than 15 percent and total growth in jobs was expected to exceed 20,000 by 2025.[12]

Shortcomings of the RPA method

This methodology was much more successful at identifying fast-growing regions with existing metropolitan centers than more sparsely populated, slower growing regions. Nor does it include a distinct marker for connectedness between cities.[12] The RPA method omits the eastern part of the Windsor-Quebec City urban corridor in Canada.

Statistics (RPA reckoning)

Notes:

- Houston appears twice (as part of Gulf Coast and Texas Triangle).

- The populations given for megalopoleis that extend into Canada and Mexico (Cascadia, Great Lakes, and Southern California) include their non-U.S. residents.

- Disconnected metropolitan areas (as defined by the RPA) are flagged with double asterisks. Disconnected areas in the upper Great Lakes region and southern Quebec are not included in RPA statistics.

Major cities not included by the RPA

Thirteen of the top 100 American primary census statistical areas are not included in any of the 11 emerging mega-regions. However, the Lexington-based CSA in Kentucky is identified by the RPA as being part of an "area of influence" of the Great Lakes megalopolis, while the Albany and Syracuse-based CSAs in Upstate New York are shown as being within the influence of the Northeastern mega-region. Similarly, the Augusta, GA and Columbia, SC-based CMA are considered influenced by the Piedmont-Atlantic megalopolis, Jackson, MS CMA by the Gulf Coast megaregion, Little Rock, AR CMA by the Texas Triangle, and the Des Moines and Omaha-based CMAs by the Great Lakes megalopolis. The El Paso, TX CMA is roughly equidistant from two megaregions, being near the southeastern edge of the Arizona Sun Corridor area of influence and the southern tip of the Front Range area of influence. This leaves Honolulu, HI, Wichita, KS, and Charleston, SC as the only top 100 American CMAs that have no mega-region affiliation of any kind as defined by the RPA.[15]

Planning

Though identification of the megaregions has gone through several iterations, the above identified are based on a set of criteria developed by Regional Plan Association, through its America 2050 initiative - a joint venture with the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. Two historic publications helped lay the foundation for this new set of criteria, the book Megalopolis by Jean Gottmann (1961)[16] and The Regions’ Growth, part of Regional Plan Association’s second regional plan[citation needed].

The relationships underpinning megaregions have become more pronounced over the second half of the 20th century as a result of decentralized land development, longer daily commutes, increased business travel, and a more footloose, flexible, knowledge workforce. The identification of new geographic scales—historically based on increased population movement from the city center to lower density areas as a megaregion presents immense opportunities from a regional planning perspective, to improve the environmental, infrastructure and other issues shared among the regions within it. The most recent and only previous attempt to plan at this scale happened more than 70 years ago, with the Tennessee Valley Authority. Political issues stymied further efforts at river basin planning and development.[8]

In 1961's Megalopolis, Gottman describes the Northeastern seaboard of the United States - or Megapologis - as "... difficult to single out ... from surrounding areas, for its limits cut across established historical divisions, such as New England and the Middle Atlantic states, and across political entities, since it includes some states entirely and others only partially." On the complex nature of this regional scale, he writes:

Some of the major characteristics of Megalopolis, which set it apart as a special region within the United States, are the high degree of concentration of people, things and functions crowded here, and also their variety. This kind of crowding and its significance cannot be described by simple measurements. Its various aspects will be shown on a number of maps, and if these could all be superimposed on one base map there would be demarcated an area in which so many kinds of crowding coincide in general (though not always in all the details of their geographical distribution) that the region is quite different from all neighboring regions and in fact from any other part of North America. The essential reason for its difference is the greater concentration here of a greater variety of kinds of crowding. Crowding of population, which may first be expressed in terms of densities per square mile, will, of course, be a major characteristic to survey. As this study aims at understanding the meaning of population density, we shall have to know the foundation that supports such crowding over such a very fast area. What do these people do? What is their average income and their standard of living? What is the distribution pattern of wealth and of certain more highly paid occupations? For example, the outstanding concentration of population in the City of New York and its immediate suburbs (a mass of more than ten million people by any count) cannot be separated from the enormous concentration in the same city of banking, insurance, wholesale, entertainment, and transportation activities. These various kinds of concentration have attracted a whole series of other activities, such as management of large corporations, retail business, travel agencies, advertising, legal and technical counseling offices, colleges, research organizations, and so on. Coexistence of all these facilities on an unequaled scale within the relatively small territory of New York City, and especially of its business district...has made the place even more attractive to additional banking, insurance, and mass media organizations.[16]

Outside the United States

The RPA report identifies megaregions that are shared between the US and Canada, and is presumably at least tangentially concerned with pan-North American issues. However, being based on largely American research, it does not clearly define the geographic extent of megaregions where they extend into Canada, a responsibility that has largely been left to Canadian geographers defining the megalopolis within their own country. The American report excludes Canadian population centres that are not deemed to be closely adjacent to US megaregions. It includes most of Southern Ontario in the Great Lakes Megaregion but excludes the St. Lawrence Valley, despite the fact that Canadian geographers usually include them as part of one larger Quebec City-Windsor Corridor.

The close relationship between large linked metropolitan regions and a nation's ability to compete in the global economy is recognized in Europe and Asia. Each has aggressively pursued strategies to manage projected population growth and strengthen economic prosperity in its large regions.

The European Spatial Development Perspective, a set of policies and strategies adopted by the European Union in 1999, is working to integrate the economies of the member regions, reduce economic disparities, and increase economic competitiveness (Faludi 2002; Deas and Lord 2006).

In East Asia, comprehensive strategic planning for large regions, centered on metropolitan areas, has become increasingly common and has progressed further than in the United States or Europe. Planning for the Hong Kong-Pearl River Delta region, for instance, aims to enhance the region's economic strength and competitiveness by overcoming local fragmentation, building on global economic cooperation, taking advantage of mutually beneficial economic factors, increasing connectivity among development nodes, and pursuing other strategic directions.[8]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Megaregions". America2050. USA: Regional Plan Association. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ "Who's Your City?: What Is a Megaregion?". March 19, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Cities: Capital for the New Megalopolis.Time magazine, November 4, 1966. Retrieved on July 19, 2010.

- ^ "About Us - America 2050". America2050. USA: Regional Plan Association. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ http://www.mi.vt.edu/uploads/megacensusreport.pdf "Beyond Megalopolis" by the Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech

- ^ http://www.des.ucdavis.edu/faculty/handy/ESP171/Readings2/Megapolitans.pdf The Rise of the Megapolitans (January 2007) by Robert E. Lang and Arthur C. Nelson. Retrieved on January 7, 2013.

- ^ a b Regional Plan Association (2006). America 2050: A Prospectus. New York, NY: Regional Plan Association.

- ^ a b c Dewar, Margaret and David Epstein (2006). "Planning for 'Megaregions' in the United States." Ann Arbor, MI: Urban and Regional Planning Program, University of Michigan.

- ^ Hagler, Yoav (2009). "Defining U.S. Megaregions." New York, NY: Regional Plan Association.

Kron, Josh (November 30, 2012). "Red State, Blue City: How the Urban-Rural Divide Is Splitting America". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 10, 2015. - ^ Carl Abbott (2015). "Cascadian Dreams: Imagining a Region Over Four Decades". Imagined Frontiers: Contemporary America and Beyond. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 111–139. ISBN 978-0-8061-5240-0.

- ^ Jerry Weitz (2014). "Employment Changes in the Spine of the Carolina Megapolitan Area: Implications for Megaregion Planning". Southeastern Geographer. 54 (3): 215–232. ISSN 1549-6929.

- ^ a b Hagler, Yoav (2009). "Defining U.S. Megaregions." New York, NY: Regional Plan Association.

- ^ "Megapolitan: Arizona's Sun Corridor". Morrison Institute for Public Policy. May 2008. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "When Phoenix, Tucson Merge". The Arizona Republic. April 9, 2006. Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ "Our Maps". America2050. USA: Regional Plan Association. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Gottman, Jean (1961). Megalopolis: The Urbanized Northeastern Seaboard of the United States. New York: Twentieth Century Fund.

Further reading

- "Are Mega-regions Relevant?", The Economist, April 14, 2008

- Richard Florida (May 4, 2009), "Mega-Regions and High-Speed Rail", The Atlantic

- Catherine L. Ross, ed. (2009). Megaregions: Planning for Global Competitiveness. Island Press. ISBN 978-1-61091-136-8. (Includes info on the USA)

- Jiang Xu; Anthony G.O. Yeh, eds. (2011). Governance and Planning of Mega-City Regions: An International Comparative Perspective. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-22913-9. (Includes info on the USA)

- John Harrison; Michael Hoyler, eds. (2015). Megaregions: Globalization's New Urban Form?. Edward Elgar Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78254-790-7. (Includes info on the USA)

- Parag Khanna (April 15, 2016), "A New Map for America", New York Times

External links

- "America2050.org". USA: Regional Plan Association.