Military–industrial complex

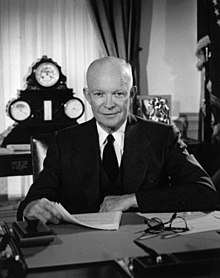

The military–industrial complex (MIC) is an informal alliance between a nation's military and the defense industry which supplies it, seen together as a vested interest which influences public policy.[1][2][3][4] The term is most often used in reference to the system behind the military of the United States, where it is most prevalent[5] and gained popularity after its use in the farewell address of President Dwight D. Eisenhower on January 17, 1961.[6][7] In 2011, the United States spent more (in absolute numbers) on its military than the next 13 nations combined.[8]

In a U.S. context, the trope is sometimes extended to military–industrial–congressional complex (MICC), adding the U.S. Congress to form a three-sided relationship termed an iron triangle.[9] These relationships include political contributions, political approval for military spending, lobbying to support bureaucracies, and oversight of the industry; or more broadly to include the entire network of contracts and flows of money and resources among individuals as well as corporations and institutions of the defense contractors, private military contractors, The Pentagon, the Congress and executive branch.[10]

A similar thesis was originally expressed by Daniel Guérin, in his 1936 book Fascism and Big Business, about the fascist government support to heavy industry. It can be defined as, "an informal and changing coalition of groups with vested psychological, moral, and material interests in the continuous development and maintenance of high levels of weaponry, in preservation of colonial markets and in military-strategic conceptions of internal affairs."[11] An exhibit of the trend was made in Franz Leopold Neumann's book Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism in 1942, a study of how Nazism came into a position of power in a democratic state.

Etymology

President of the United States (and five-star general during World War II) Dwight D. Eisenhower used the term in his Farewell Address to the Nation on January 17, 1961:

A vital element in keeping the peace is our military establishment. Our arms must be mighty, ready for instant action, so that no potential aggressor may be tempted to risk his own destruction...

This conjunction of an immense military establishment and a large arms industry is new in the American experience. The total influence — economic, political, even spiritual — is felt in every city, every statehouse, every office of the federal government. We recognize the imperative need for this development. Yet we must not fail to comprehend its grave implications. Our toil, resources and livelihood are all involved; so is the very structure of our society. In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military–industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists, and will persist.

We must never let the weight of this combination endanger our liberties or democratic processes. We should take nothing for granted. Only an alert and knowledgeable citizenry can compel the proper meshing of the huge industrial and military machinery of defense with our peaceful methods and goals so that security and liberty may prosper together.

The phrase was thought to have been "war-based" industrial complex before becoming "military" in later drafts of Eisenhower's speech, a claim passed on only by oral history.[12] Geoffrey Perret, in his biography of Eisenhower, claims that, in one draft of the speech, the phrase was "military–industrial–congressional complex", indicating the essential role that the United States Congress plays in the propagation of the military industry, but the word "congressional" was dropped from the final version to appease the then-currently elected officials.[13] James Ledbetter calls this a "stubborn misconception" not supported by any evidence; likewise a claim by Douglas Brinkley that it was originally "military–industrial–scientific complex".[13][14] Additionally, Henry Giroux claims that it was originally "military–industrial–academic complex".[15] The actual authors of the speech were Eisenhower's speechwriters Ralph E. Williams and Malcolm Moos.[16]

Attempts to conceptualize something similar to a modern "military–industrial complex" existed before Eisenhower's address. Ledbetter finds the precise term used in 1947 in close to its later meaning in an article in Foreign Affairs by Winfield W. Riefler.[13][17] In 1956, sociologist C. Wright Mills had claimed in his book The Power Elite that a class of military, business, and political leaders, driven by mutual interests, were the real leaders of the state, and were effectively beyond democratic control. Friedrich Hayek mentions in his 1944 book The Road to Serfdom the danger of a support of monopolistic organisation of industry from World War II political remnants:

Another element which after this war is likely to strengthen the tendencies in this direction will be some of the men who during the war have tasted the powers of coercive control and will find it difficult to reconcile themselves with the humbler roles they will then have to play [in peaceful times]."[18]

Vietnam War–era activists, such as Seymour Melman, referred frequently to the concept, and use continued throughout the Cold War: George F. Kennan wrote in his preface to Norman Cousins's 1987 book The Pathology of Power, "Were the Soviet Union to sink tomorrow under the waters of the ocean, the American military–industrial complex would have to remain, substantially unchanged, until some other adversary could be invented. Anything else would be an unacceptable shock to the American economy."[19]

In the late 1990s James Kurth asserted, "By the mid-1980s,[...]the term had largely fallen out of public discussion." He went on to argue that "[w]hatever the power of arguments about the influence of the military–industrial complex on weapons procurement during the Cold War, they are much less relevant to the current era."[20]

Contemporary students and critics of American militarism continue to refer to and employ the term, however. For example, historian Chalmers Johnson uses words from the second, third, and fourth paragraphs quoted above from Eisenhower's address as an epigraph to Chapter Two ("The Roots of American Militarism") of a recent volume[21] on this subject. P. W. Singer's book concerning private military companies illustrates contemporary ways in which industry, particularly an information-based one, still interacts with the U.S. Government and the Pentagon.[22]

The expressions permanent war economy and war corporatism are related concepts that have also been used in association with this term. The term is also used to describe comparable collusion in other political entities such as the German Empire (prior to and through the first world war), Britain, France and (post-Soviet) Russia.[citation needed]

Linguist and anarchist theorist Noam Chomsky has suggested that "military–industrial complex" is a misnomer because (as he considers it) the phenomenon in question "is not specifically military."[23] He claims, "There is no military–industrial complex: it's just the industrial system operating under one or another pretext (defense was a pretext for a long time)."[24]

History

Whilst the term originated in the 1960s and has been applied since, the concept of co-ordination between government, the military, and the arms industry largely finds its roots since the private sector began providing weaponry to government-run forces. The relationship between government and the defense industry can include political contracts placed for weapons, general bureaucratic oversight and organized lobbying on the part of the defense companies for the maintenance of their interests.

For centuries, many governments owned and operated their own arms manufacturing companies—such as naval yards and arsenals. Governments also legislated to maintain state monopolies. As limited liability companies attracted capital to develop technology, governments saw the need to develop relationships with companies who could supply weaponry. By the late 19th century the new complexity of modern warfare required large subsets of industry to be devoted to the research and development of rapidly maturing technologies. Rifles, automatic firearms, artillery and gunboats, and later, mechanized armour, aircraft and missiles required specialized knowledge and technology to build. For this reason, governments increasingly began to integrate private firms into the war effort by contracting out weapons production to them. It was this relationship that marked the creation of the military–industrial complex.

The first modern military–industrial complexes arose in Britain, France and Germany in the 1880s and 1890s as part of the increasing need to defend their respective empires both on the ground and at sea.[citation needed] The naval rivalry between Britain and Germany, and the French desire for revenge against the German Empire for the defeat of the Franco-Prussian war, was significant in the inception, growth and development of these MICs. Arguably, the existence of these three nations' respective MICs may have helped to fuel their military tensions.[citation needed].

Admiral Jackie Fisher, First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy, was influential in the shift toward faster integration of technology into military usage, resulting in strengthening relationships between the military, and innovative private companies.

A noteworthy industrialist in the development of large private defense firms, was William Armstrong, who founded the Elswick Ordnance Company, which embarked on a massive rearmament program for the British Army after the Crimean War in the 1860s. In 1884 he opened a shipyard at Elswick that specialised in warship production. It was the only factory in the world that could build a battleship and arm it completely. Other noteworthy industrialists involved in the expanding arms industry of the time included Alfred Krupp, Samuel Colt, Alfred Nobel, and Joseph Whitworth.

In a fictional work, Death Comes for the Archbishop, by Willa Cather, 1927, set in the 1880s in the American Southwest / New Mexico / Northern Mexico, Cather wrote this passage on Page 200:

"… Latour used to wonder if there would ever be an end to the Indian wars while there was one Navajo or Apache left alive. Too many traders and manufacturers made a rich profit out of that warfare; a political machine and immense capital were employed to keep it going. …"

After World War I, most countries did not demobilize; instead there was a shift toward faster integration of technology into military usage and strengthening relationships between the military and private companies in Britain, France and Germany. In the newly formed USSR, military production was controlled entirely by the state. The period after the war also saw the emergence of MICs in both Japan and the United States. During the rearmament period in the late 1930s in Europe, military spending doubled.

The economic effect of World War II was profound, as military spending shot up and new methods of taxation and spending were adopted. The war also saw the first massive military research programs, notably the Allied project to create nuclear weapons.

The end of the war saw the emergence of Cold War rivalry which involved a constant arms race between the two new superpowers, the USA and USSR. The low-intensity, but constant threat of conflict created an atmosphere where there was a constant perception of the need for sustained military procurement. It was due to these factors that President Dwight Eisenhower introduced the concept of the 'military–industrial complex' to the public consciousness in his "Farewell Address". Currently, the annual military expenditure of the United States accounts for about 47% of the world's total arms expenditures.[25]

The table below lists major United States armament manufacturers from World War II through the Eisenhower presidency. Following each name, the columns show the ranking of the military prime contractor in terms of total value of armaments produced from June 1940 through September 1944, during fiscal years 1950 through 1953, and during fiscal years 1958 through 1960.[26]

| Company | WW2 | Korea | 1960 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boeing | 12 | 2 | 1 |

| General Dynamics | 4 | 8 | 2 |

| Lockheed Corporation | 10 | 7 | 3 |

| General Electric | 9 | 3 | 4 |

| North American Aviation | 11 | 9 | 5 |

| United Aircraft | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| AT&T Corporation | 13 | 13 | 7 |

| Douglas Aircraft Company | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| Glenn L. Martin Company | 14 | 23 | 9 |

| Hughes Aircraft Company | 100+ | 25 | 10 |

| Sperry Corporation | 19 | 18 | 11 |

| Raytheon | 71 | 42 | 12 |

| McDonnell Aircraft | 100+ | 21 | 13 |

| RCA | 43 | 22 | 14 |

| IBM | 100+ | 44 | 15 |

In 1977, following the Vietnam war, U.S. President Jimmy Carter began his presidency with what historian Michael Sherry has called "a determination to break from America's militarized past."[27] However, increased defense spending in the era of President Ronald Reagan was seen by some to have brought the MIC back into prominence.

Following the Cold War

U.S. defense contractors bewailed what they called declining government weapons spending at the end of the Cold War.[28][29] They saw escalation of tensions, such as with Russia over Ukraine, as new opportunities for increased weapons sales, and have pushed the political system, both directly and through industry lobby groups such as the National Defense Industrial Association, to spend more on military hardware. Pentagon contractor-funded American think tanks such as the Lexington Institute and the Atlantic Council have also demanded increased spending in view of the perceived Russian threat.[29][30] Independent Western observers such as William Hartung, director of the Arms & Security Project at the Center for International Policy, noted that “Russian saber-rattling has additional benefits for weapons makers because it has become a standard part of the argument for higher Pentagon spending—even though the Pentagon already has more than enough money to address any actual threat to the United States."[29]

Current applications

According to SIPRI, total world spending on military expenses in 2009 was $1.531 trillion US dollars. 46.5% of this total, roughly $712 billion US dollars, was spent by the United States.[31] The privatization of the production and invention of military technology also leads to a complicated relationship with significant research and development of many technologies.

The military budget of the United States for the 2009 fiscal year was $515.4 billion. Adding emergency discretionary spending and supplemental spending brings the sum to $651.2 billion.[32] This does not include many military-related items that are outside of the Defense Department budget. Overall the United States government is spending about $1 trillion annually on defense-related purposes.[33]

The defense industry tends to contribute heavily to incumbent members of Congress.[34]

In a 2012 news story, Salon reported, "Despite a decline in global arms sales in 2010 due to recessionary pressures, the U.S. increased its market share, accounting for a whopping 53 percent of the trade that year. Last year saw the U.S. on pace to deliver more than $46 billion in foreign arms sales."[35]

The concept of a military-industrial complex has been expanded to include the entertainment and creative[36] industries. For an example in practice, Matthew Brummer describes Japan's Manga Military and how the Ministry of Defense uses popular culture and the moe that it engenders to shape domestic and international perceptions.

See also

- Works

- The Complex: How the Military Invades Our Everyday Lives

- War Is a Racket (1935 book by Smedley Butler)

- Why We Fight (2005 documentary film by Eugene Jarecki)

Notes

- ^ "military industrial complex". American Heritage Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2015. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "definition of military-industrial complex (American English)". OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Definition of Military–industrial complex". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ Roland, Alex (2009-06-22). "The Military-Industrial Complex: lobby and trope". In Bacevich, Andrew J. (ed.). The Long War: A New History of U.S. National Security Policy Since World War II. Columbia University Press. pp. 335–370. ISBN 9780231131599.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ "SIPRI Year Book 2008; Armaments, Disarmaments and International Security" Oxford University Press 2008 ISBN 9780199548958 Pages 255–56 view on google books

- ^ "The Military–Industrial Complex; The Farewell Address of Presidente Eisenhower" Basements publications 2006 ISBN 0976642395

- ^ Held, David; McGrew, Anthony G.; Goldblatt, David (1999). "The expanding reach of organized violence". In Perraton, Jonathan (ed.). Global Transformations: Politics, Economics and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780804736275.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Plumer, Brad (January 7, 2013), "America's staggering defense budget, in charts", The Washington Post

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Higgs, Robert (2006-05-25). Depression, War, and Cold War : Studies in Political Economy: Studies in Political Economy. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. ix, 138. ISBN 9780195346084. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- ^ "Long-term Historical Reflection on the Rise of Military-Industrial, Managerial Statism or "Military-Industrial Complexes"". Kimball Files. University of Oregon. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ Pursell, C. (1972). The military–industrial complex. Harper & Row Publishers, New York, New York.

- ^ John Milburn (December 10, 2010). "Papers shed light on Eisenhower's farewell address". Associated Press. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c Ledbetter, James (25 January 2011). "Guest Post: 50 Years of the "Military–Industrial Complex"". Schott's Vocab. New York Times. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Brinkley, Douglas (September 2001). "Eisenhower; His farewell speech as President inaugurated the spirit of the 1960s". American Heritage. 52 (6). Archived from the original on 23 March 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

{{cite journal}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 23 March 2006 suggested (help) - ^ Giroux, Henry (June 2007). "The University in Chains: Confronting the Military–Industrial–Academic Complex". Paradigm Publishers. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 20 August 2007 suggested (help) - ^ Griffin, Charles "New Light on Eisenhower's Farewell Address," in Presidential Studies Quarterly 22 (Summer 1992): 469–479

- ^ Riefler, Winfield W. (October 1947). "Our Economic Contribution to Victory". Foreign Affairs. 26 (1): 90–103. JSTOR 20030091.

- ^ Hayek, F.A., (1976) "The Road to Serfdom," London: Routledge, p. 146, note 1

- ^ Kennan, George Frost (1997). At a Century's Ending: Reflections 1982–1995. W.W. Norton and Company. p. 118.

- ^ Kurth 1999.

- ^ The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004. p. 39

- ^ Corporate Warriors: The Rise of the Privatized Military Industry. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2003.

- ^ "War Crimes and Imperial Fantasies, Noam Chomsky interviewed by David Barsamian". chomsky.info.

- ^ In On Power, Dissent, and Racism: a Series of Discussions with Noam Chomsky, Baraka Productions, 2003.

- ^ "Recent Trends in Military Expenditure".

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.613

- ^ Sherry, Michael S. (1995). In the Shadow of War: The United States since the 1930s. New Haven & London: Yale University Press. p. 342. ISBN 0-300-07263-5.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Thompson Reuters Streetevents, 8 December 2015, "L-3 Communications Holding Inc. Investors Conference," page 3, http://www.l-3com.com/sites/default/files/pdf/investor-pdf/2015_investor_conference_transcript.pdf

- ^ a b c The Intercept, 19 August 2016, "U.S. Defense Contractors Tell Investors Russian Threat is Great for Business," https://theintercept.com/2016/08/19/nato-weapons-industry/

- ^ U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Armed Services, Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, 11 May 2016, Testimony of M. Thomas Davis, Senior Fellow, National Defense Industrial Association, "U.S. Industry Perspective on the Department of Defense's Policies, Roles and Responsibilities for Foreign Military Sales," http://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS06/20160511/104900/HHRG-114-AS06-Bio-DavisT-20160511.pdf

- ^ Anup Shah. "World Military Spending". Retrieved October 6, 2010.

- ^ Gpoaccess.gov

- ^ Robert Higgs. "The Trillion-Dollar Defense Budget Is Already Here". Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ Jen DiMascio. "Defense goes all-in for incumbents - Jen DiMascio". POLITICO.

- ^ "America, arms-dealer to the world," Salon, January 24, 2012.

- ^ Diplomat, Matthew Brummer, The. "Japan: The Manga Military". The Diplomat. Retrieved 2016-01-22.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

References

- DeGroot, Gerard J. Blighty: British Society in the Era of the Great War, 144, London & New York: Longman, 1996, ISBN 0-582-06138-5

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. Public Papers of the Presidents, 1035–40. 1960.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. "Farewell Address." In The Annals of America. Vol. 18. 1961–1968: The Burdens of World Power, 1–5. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1968.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. President Eisenhower's Farewell Address, Wikisource.

- Hartung, William D. "Eisenhower's Warning: The Military–Industrial Complex Forty Years Later." World Policy Journal 18, no. 1 (Spring 2001).

- Johnson, Chalmers The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic, New York: Metropolitan Books, 2004

- Kurth, James. "Military–Industrial Complex." In The Oxford Companion to American Military History, ed. John Whiteclay Chambers II, 440–2. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Nelson, Lars-Erik. "Military–Industrial Man." In New York Review of Books 47, no. 20 (Dec. 21, 2000): 6.

- Nieburg, H. L. In the Name of Science, Quadrangle Books, 1970

- Mills, C. Wright."Power Elite", New York, 1956

Further reading

- Adams, Gordon, The Iron Triangle: The Politics of Defense Contracting, 1981.

- Andreas, Joel, Addicted to War: Why the U.S. Can't Kick Militarism, ISBN 1-904859-01-1.

- Cochran, Thomas B., William M. Arkin, Robert S. Norris, Milton M. Hoenig, U.S. Nuclear Warhead Production Harper and Row, 1987, ISBN 0-88730-125-8

- Colby, Gerard, DuPont Dynasty. New York: Lyle Stuart, 1984.

- Friedman, George and Meredith, The Future of War: Power, Technology and American World Dominance in the 21st Century, Crown, 1996, ISBN 0-517-70403-X

- Hossein-Zadeh, Ismael, The Political Economy of US Militarism. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2006.

- Keller, William W., Arm in Arm: The Political Economy of the Global Arms Trade. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

- Kelly, Brian, Adventures in Porkland: How Washington Wastes Your Money and Why They Won't Stop, Villard, 1992, ISBN 0-679-40656-5

- Lassman, Thomas C. "Putting the Military Back into the History of the Military-Industrial Complex: The Management of Technological Innovation in the U.S. Army, 1945–1960," Isis (2015) 106#1 pp. 94–120 in JSTOR

- McDougall, Walter A., ...The Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age, Basic Books, 1985, (Pulitzer Prize for History) ISBN 0-8018-5748-1

- Melman, Seymour, Pentagon Capitalism: The Political Economy of War, McGraw Hill, 1970

- Melman, Seymour, (ed.) The War Economy of the United States: Readings in Military Industry and Economy, New York: St. Martin's Press, 1971.

- Mills, C Wright, The Power Elite. New York, 1956.

- Mollenhoff, Clark R., The Pentagon: Politics, Profits and Plunder. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1967

- Patterson, Walter C., The Plutonium Business and the Spread of the Bomb, Sierra Club, 1984, ISBN 0-87156-837-3

- Pasztor, Andy, When the Pentagon Was for Sale: Inside America's Biggest Defense Scandal, Scribner, 1995, ISBN 0-684-19516-X

- Pierre, Andrew J., The Global Politics of Arms Sales. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1982.

- Sampson, Anthony, The Arms Bazaar: From Lebanon to Lockheed. New York: Bantam Books, 1977.

- St. Clair, Jeffery, Grand Theft Pentagon: Tales of Corruption and Profiteering in the War on Terror, Common Courage Press (July 1, 2005).

- Sweetman, Bill, "In search of the Pentagon's billion dollar hidden budgets—how the US keeps its R&D spending under wraps", from Jane's International Defence Review, online

- Thorpe, Rebecca U. The American Warfare State: The Domestic Politics of Military Spending. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Watry, David M. Diplomacy at the Brink: Eisenhower, Churchill, and Eden in the Cold War. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2014.

- Weinberger, Sharon. Imaginary Weapons. New York: Nation Books, 2006.

External links

- Khaki capitalism, The Economist, Dec 3rd 2011

- Militaryindustrialcomplex.com, Features running daily, weekly and monthly defense spending totals plus Contract Archives section.

- C. Wright Mills, Structure of Power in American Society, British Journal of Sociology,Vol.9.No.1 1958

- Dwight David Eisenhower, Farewell Address On the military–industrial complex and the government–universities collusion – 17 January 1961

- William McGaffin and Erwin Knoll, The military–industrial complex, An analysis of the phenomenon written in 1969

- The Cost of War & Today's Military Industrial Complex, National Public Radio, 8 January 2003.

- Leading Defense Industry news source

- Human Rights First; Private Security Contractors at War: Ending the Culture of Impunity (2008)

- Fifty Years After Eisenhower's Farewell Address, A Look at the Military–Industrial Complex – video report by Democracy Now!

- Military Industrial Complex – video reports by The Real News

- Online documents, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library

- 50th Anniversary of Eisenhower's Farewell Address - Eisenhower Institute

- Part 1 - Anniversary Discussion of Eisenhower's Farewell Address - Gettysburg College

- Part 2 - Anniversary Discussion of Eisenhower's Farewell Address - Gettysburg College