Hassan I of Morocco

| Hassan bin Mohammed الحسن بن محمد | |

|---|---|

| Amir al-Mu'minin | |

Mawlay Hassan I in 1873 | |

| Sultan of Morocco | |

| Reign | 1873–1894 |

| Coronation | 25 September 1873 |

| Predecessor | Sidi Muhammad IV |

| Successor | Mawlay Abd al-Aziz |

| Born | 1836 Fes, Morocco |

| Died | 9 June 1894 (aged 57–58) Tadla, Morocco[1] |

| Burial | |

| Wives | among others:[2][3] Princess Lalla Zaynab bint Abbas[4][5] Lalla Aliya al-Settatiya[6] (before 1876) Lalla Khadija bint al-Arbi[7] Lalla Zohra bint al-Hajj Maathi[8] Lalla Ruqaya Al Amrani[9][10] |

| Issue | 27 children, including:[11] Mohammed bin Hassan Fatima Zahra bint Hassan Abd al-Hafid bin Hassan Abd al-Aziz bin Hassan Yusef bin Hassan |

| House | 'Alawi dynasty |

| Father | Muhammad bin Abd al-Rahman |

| Mother | Lalla Safiya bint Maimun bin Mohammed al-Alaoui[12] |

| Religion | Maliki Sunni Islam |

Mawlay Hassan bin Mohammed (Arabic: الحسن بن محمد, romanized: al-Ḥasan bin Muḥammad), known as Hassan I (Arabic: الحسن الأول, romanized: al-Ḥasan al-Awwal), born in 1836 in Fes and died on 9 June 1894 in Tadla, was a sultan of Morocco from 12 September 1873 to 7 June 1894, as a ruler of the 'Alawi dynasty.[13] He was proclaimed sultan after the death of his father Mawlay Muhammad bin Abd al-Rahman.[14][15] Mawlay Hassan was among the most successful sultans. He increased the power of the makhzen in Morocco and at a time when so much of the rest of Africa was falling under foreign control, he brought in military and administrative reforms to strengthen the regime within its own territory, and he carried out an active military and diplomatic program on the periphery.[15] He died on 9 June 1894 and was succeeded by his son Abd al-Aziz.[15]

Reign

[edit]| History of Morocco |

|---|

|

Early reign and rebellion in Fes

[edit]

Son of the sultan Muhammad IV, Mawlay (Moulay) Hassan was proclaimed sultan of Morocco on the death of his father in 1873. His first action was to crush an urban revolt in the capital Fes in 1874, which he had to besiege for a few months.[16][17] The tanners rose up in protest "raging like lions and tigers" through the streets of Fes, pillaging the house of Muhammad Bennis, the Minister of Finance, turning Fes into a battleground.[18] Mawlay Hassan I, who was on campaign sent letters calling for the pacification of the city. Shortly after, the hated tax collectors were withdrawn, and the rebellion halted.[18] The tax collectors soon reappeared, leading to the rebellion commencing again more violently. The local Fes militiamen took up positions in minarets of Fes al-Bali and fired down on the army, but the two sides later negotiated peace and the rebellion was definitely terminated.[18] Of strong Arab culture, he did not know any foreign language,[16] although Mawlay Hassan I was a conservative ruler, he realised the need for modernization and the reform policy of his father.[16]

He strived to maintain the cohesion of his kingdom through political, military, and religious action, in the face of European threats on its periphery, and internal rebellions, He initiated reforms. He strived to ensure the loyalty of the great chiefs of the south. He did not hesitate to appoint local qaids like Sheikh Ma al-'Aynayn who gave him the Bay'a, the pledge of allegiance in Islamic Sharia law. He tried to modernize his army, and lead several expeditions to assert his authority, such as to the Sous in 1882 and 1886, to the Rif in 1887, and to Tafilalt in 1893.[16][19]

Relations with Europe

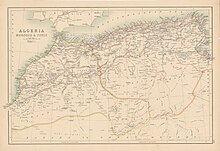

[edit]Sultan Hassan I managed to maintain the independence of Morocco while neighbouring states fell under European influence, such as Tunis which was conquered by France in 1881 and Egypt which was occupied by Britain in 1882.[20]

Both Spain and France hoped for a weak Makhzen government of Morocco, while the British hoped for the opposite, a reformed Moroccan state which could stand on its own.[20] Aware of this, Mawlay Hassan called for an international conference on the issue, and the Treaty of Madrid was signed on 3 July 1880 to limit the practice, an important event of Mawlay Hassan's reign. Instead of reducing foreign interference, the Makhzen had to grant concessions such as granting foreigners rights to own land in the countryside, something which Great Britain was pushing for all along.[20] This was followed by French incursions into the region of Touat in the south, which was considered Moroccan territory.[20] This treaty effectively gave international approval and protection for lands which had been captured by foreign powers. This set the stage for the French protectorate in Morocco beginning in 1912.[20]

In 1879 and again in 1880, the British Legation in Morocco was informed by Moroccan authorities that the domains of the Sultan Moulay Hassan reached as far as the Senegal River and included the town of Timbuktu and neighboring portions of Sudan, a claim based on the fact that the predecessors of Moulay Hassan had always considered themselves as sovereigns of these regions.[21] Since 1879, the British occupied Tarfaya and built a fortification there in 1882 known as Port Victoria. It was not until 1886 that the sultan sent a military expedition there, damaging the fort and forcing Donald MacKenzie to leave.[22] The sultan's expedition to Sus in 1886 was followed a year later by the Spanish occupation of Dakhla on the Saharan coast. Mawlay Hassan responded by appointing a khalifa (governor) over the Sahara, Ma al-'Aynayn.[22] In 1888 Timbuktu requested that Moulay Hassan send a governor to help the town against the French forces advancing into the Niger basin.[23]

Military reform

[edit]Mawlay Hassan I continued to expand the military reforms started by his father Muhammad IV. The new and reformed 'Askar al-Nizami introduced by sultan Abd al-Rahman in 1845 after the Battle of Isly was expanded by Mawlay Hassan I to the size of 25,000 men and 1,000 artillery. The sultan also enhanced the Moroccan coastal defences with batteries of large caliber cannon, and in 1888 built an arms factory in Fes known as Dar al-Makina, however production in it was little and costly.[24] To train the reformed Moroccan army, Mawlay Hassan I sent students to London, but in 1876, the sultan hired Harry MacLean, a British officer based in Gibraltar, who designed a military uniform in Arab-style, and learned to speak excellent Arabic.[25]

Every year from spring to fall, Mawlay Hassan I was on campaign, and lead expeditions to all parts of the kingdom. One of Mawlay Hassan's campaigns was dealing with the Darqawa uprising near Figuig in the fall of 1887, which was quickly suppressed.[24] Particularly well known is the journey Hassan I undertook in 1893. He went from Fes (leaving on 29 June) to Marrakech, passing through the Tafilalt, the sand dunes of Erg Chebbi, the valley of the Dades with the majestic gorges of the Todra, Warzazat, the Kasbah of Aït Benhaddou, the high passage along Telouet, the Tichka pass (2260 m) in the high Atlas, Guelmim port of the Western Sahara. The voyage took six months and succeeded in its objective of reuniting and pacifying the tribes of several regions. The Krupp cannon he gave on this occasion to the qaid of Telouet (member of the now famous Glaoua family) is still on display in the center of Warzazat. In 1881 he founded Tiznit.[26]

Hassan I appointed Mouha Zayani as qaid of the Zayanes in Khenifra in 1877. Mouha Zayani was to be an important figure in the 20th century colonial war against France. In 1887 he appointed sheikh Ma al-'Aynayn as his qaid in Western Sahara. Ma al-'Aynayn too played an important role in the struggle for independence of Morocco.[26]

Moulay Hassan decided to reinstate the old Moroccan administration in the Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt. The first Moroccan envoys reached the Saharan oases in 1889 and in 1890. In 1891 Moulay Hassan called on the oases peoples to begin paying taxes, thus formalizing the recognition of his suzerainty. That same year the Touat and the oases which lay along the Oued Saoura were placed under the authority of the son of the Moroccan khalifa who resided in the Tafilalt. Then, in 1892, a complete administrative organization was established in all of the Gourara-Touat-Tidikelt. The Moroccan Government even went so far as to extend to the qaids of the Touareg of the Ahenet and the Hoggar a formal recognition that they were dependent subjects of the Sultan. In 1892 and 1893, the Moroccans further solidified their control in the Guir-Zouzfana basin and along the oued Saoura by investing with official authority the qaids from all of the nomadic and sedentary tribes of the region (this included the Doui Menia and Oulad Djerir tribes, the most important nomads of the Guir-Zousfana basin; the oasis of Igli; and the sedentary Beni Goumi people who lived along the banks of the Oued Zouzfana).[27]

Marriages, concubines and children

[edit]Sultan Moulay Hassan I married eight times and had a harem of slave concubines. Here is the list of his descendants, first listing his descendants with his wives:[28][29]

Princess Lalla Zaynab bint Abbas[30][31] their marriage took place before 1875.[32] She is the daughter of Prince Moulay Abbas ben Abd al-Rahman, her mother is a woman named Maimouna.[30] Together they had:

- Sidi Mohammed[32][33] the eldest son of Moulay Hassan I, he was his father's heir until his rebellion, when he was evicted;[34]

- Moulay Zain al Abdine.[30]

Lalla Aliya al-Settatiya,[35][36] their marriage took place before 1876.[37] Together they had:

- Sultan Moulay Abd al-Hafid.

Lalla Khadija bint al-Arbi,[28] together they had:[38]

- Moulay Abderrahmane;

- Moulay al-Kabir.

Lalla Zohra bint al-Hajj Maathi,[28] together they had:[39]

- Moulay Bil-Ghayth;

- Moulay Abou Bakar.

Sharifa Lalla Ruqaya Al Amrani,[34][40] his favorite wife. She is from an illustrious Moroccan family. After the disgrace of her step-son Sidi Mohammed, Sultan Moulay Hassan I hastened to name her son Moulay Abdelaziz official heir to the crown. Their children are:[41]

- Lalla Oum Kelthoum;

- Lalla Nezha;

- Sultan Moulay Abdelaziz;

- Lalla Chérifa;

- Moulay Abdelkébir.

Lalla Kinza al-Daouia:[42] she divorced from the sultan and remarried to Abdallah al-Daouia then to Mohammed el-Talba. From her marriage to the sultan she had:[42]

- Moulay al-Mamun, he is the father of Princess Lalla Hanila bint Mamoun;[43]

- Moulay al-Amin;

- Moulay Othman;

- Moulay Mohammed al-Anwar.

Lalla Oum al-Khair,[44] her last name is not retained, together they had:[44]

- Moulay Abdallah, he died on December 15, 1883;[44]

- Twins, Sultan Moulay Yusef[45] and Prince Moulay Mohammed el-Tahar,[45][44] the latter is the father of Princess Lalla Abla, the mother of King Hassan II;[45]

- Moulay Jaafar;

- Sidi Mohammed el Sghir;

- Moulay Talib;

Lalla Oum Zayda,[46] her last name is not retained, together they had:[46]

- Moulay Mohammed al-Mehdi;

- another son named Abdallah;

- Lalla Abla.

Sultan Moulay Hassan I is also the father of:

- Princess Lalla Fatima Zahra (died in 1894),[47] a woman of letters and faqīha who donated a large part of her princely literary collection[48] for the library of the University of al-Qarawiyyin in Fes.[48]

Moulay Hassan I had a harem of slave concubines (jawari), however the precise number of his slave concubines is largely unknown, leaving room for speculation.[49] Only the partial identity of nine of his slave concubines from the Caucasus are known.[50] His descent with them are not specified:

Aisha (Ayesha):[49] she is a slave concubine of Georgian origin. Purchased in Istanbul in 1876 by the vizier Sidi Gharnat,[49] she was the favorite of Sultan Moulay Hassan I during the sixteen years she remained in his harem.[49]

Nour: [50] Circassian slave purchased in Turkey by Hadj El Arbi Brichi and offered to the sultan as a slave concubine.[50] She is probably the beautiful Circassian bought for 25,000 francs at the Istanbul bazaar.[50] But the date she joined the sultan's harem is not specified.

Suchet adds a "batch"[49] of four other Circassian women of great beauty and accomplished talents purchased for 100,000 francs in 1878 in Cairo[49] and another three other Circassian slave concubines, without further details.[49]

Death

[edit]On 9 June 1894, Mawlay Hassan I died from illness near Wadi al-Ubayd in the region of Tadla. Since the army was still in enemy territory, his chamberlain and Grand Wazir Ahmad bin Musa kept the death a secret, ordering the ministers to not reveal the news.[51] The sultan's body was taken to Rabat and buried there,[28][52] in a qubba next to Dar al-Makhzen[53] which also contains the tomb of his ancestor Sidi Mohammed III.[53] Mawlay Hassan was succeeded by his son Abd al-Aziz, thirteen years old at the time, and ruled under the regency of his father's former Grand Wazir, Ahmad bin Musa, until his death from heart failure in 1900.[28]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Morocco (Alaoui Dynasty)". 2005-08-29. Archived from the original on 2005-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "alHassan Al Hassan, I". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ "Morocco (Alaoui Dynasty)". 2005-08-29. Archived from the original on 2005-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "Family tree of Moulay Hassan I el-ALAOUI". Geneanet. Retrieved 2022-09-21.

H.H. Lalla Zainab bint Abbas, daughter of H.H. Mulay Abbas bin 'Abdu'l-Rahman

- ^ Dartois, Marie-France (2008). Agadir et le sud marocain: à la recherche du temps passé, des origines au tremblement de terre du 29 février 1960 (in French). Courcelles. p. 417. ISBN 978-2-916569-30-7.

the eldest son of the sultan, Moulay Mohammed, is proclaimed at the instigation of his mother the Cherifa.

- ^ Mission Scientifique Du Maroc (1915). Villes et Tribus du Maroc. Documents Et Renseignements Publiés Sous Les Auspices De La Residence Generale. Casablanca Et Les Chaouia. TOME I (in French). Paris: Ernest Leroux. p. 180.

- ^ Daughter of al-Arbi

- ^ Daughter of al-Hajj Maathi

- ^ Ganān, Jamāl (1975). Les relations franco-allemandes et les affaires marocaines de 1901 à 1911 (in French). SNED. p. 14.

- ^ Lahnite, Abraham (2011). La politique berbère du protectorat français au Maroc, 1912-1956: Les conditions d'établissement du Traité de Fez (in French). Harmattan. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-296-54980-7.

- ^ Says, Yaf (2020-06-06). "Moulay Mhammed, l'héritier dépossédé". Zamane (in French). Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "Safiyyah Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. Retrieved 2022-10-21.

- ^ M. Th. Houtsma: E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam 1913–1936. S. 603; also: Anmerkung über den Todesort and in The Daily Telegraph at the death of his daughter Lalla Fatima Zohra, 22. October 2003, (English)

- ^ "أولى الصور في تاريخ المغرب، الأولى في الفنيدق/تطوان سنة 1859 والثانية للأمير المولى العباس سنة 1860". Alifpost. 9 June 2013. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ^ a b c "Hassan I | sultan of Morocco | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2022-04-13.

- ^ a b c d Universalis, Encyclopædia. "HASSAN Ier". Encyclopædia Universalis (in French). Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ Lugan, Bernard (2016-06-02). Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord: Des origines à nos jours (in French). Editions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-08535-7.

- ^ a b c Miller, Susan Gilson (2013-04-15). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-81070-8.

- ^ Lugan, Bernard (2016-06-02). Histoire de l'Afrique du Nord: Des origines à nos jours (in French). Editions du Rocher. ISBN 978-2-268-08535-7.

- ^ a b c d e Miller, Susan Gilson (2013-04-15). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-81070-8.

- ^ Trout, Frank E. (1969). Morocco's Saharan Frontiers. Librairie Droz. p. 137. ISBN 978-2-600-04495-0.

- ^ a b Pennell, C. R. (2013-10-01). Morocco: From Empire to Independence. Simon and Schuster. pp. 125–126. ISBN 978-1-78074-455-1.

- ^ Trout, Frank E. (1969). Morocco's Saharan Frontiers. Librairie Droz. p. 153. ISBN 978-2-600-04495-0.

- ^ a b Miller, Susan Gilson (2013-04-15). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-521-81070-8.

- ^ Pennell, C. R. (2013-10-01). Morocco: From Empire to Independence. Simon and Schuster. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-78074-455-1.

- ^ a b Marchat, Henry (1970). "Les origines diplomatiques du "Maroc espagnol" (1880-1912)". Revue des mondes musulmans et de la Méditerranée. 7 (1): 101–170. doi:10.3406/remmm.1970.1061.

- ^ Trout, Frank E. (1969). Morocco's Saharan Frontiers. Librairie Droz. p. 27. ISBN 978-2-600-04495-0.

- ^ a b c d e "Morocco (Alaoui Dynasty)". 2005-08-29. Archived from the original on 2005-08-29. Retrieved 2021-07-11.

- ^ "alHassan Al Hassan, I". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b c "Zainab Belabbes Alaoui". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Dartois, Marie-France (2008). Agadir et le sud marocain: à la recherche du temps passé, des origines au tremblement de terre du 29 février 1960 (in French). Courcelles. p. 417. ISBN 978-2-916569-30-7.

- ^ a b "Mohammed Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Says, Yaf (2020-06-06). "Moulay Mhammed, l'héritier dépossédé". Zamane (in French). Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b Ganān, Jamāl (1975). Les relations franco-allemandes et les affaires marocaines de 1901 à 1911 (in French). SNED. p. 14.

- ^ "Aliya Al Sattatiya". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Mission scientifique du Maroc (1915). Villes et tribus du Maroc : Casablanca et les Châouïa. Vol. I. Paris: Ernest Leroux. p. 180.

- ^ "AbdulHafeeth Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ "Khadija Al Arabi". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ "Zohra Ma'athi". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Lahnite, Abraham (2011). La politique berbère du protectorat français au Maroc, 1912-1956: Les conditions d'établissement du Traité de Fez (in French). Harmattan. p. 44. ISBN 978-2-296-54980-7.

- ^ Morocco), Hassan II (King of (1979). Discours et interviews de SM Hassan II (in French). Ministère d'État chargé de l'information, Royaume du Maroc. p. 176.

- ^ a b "Kinza Al Daouia". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ "? Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b c d "Um Khair". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ a b c ibn zaydan. durafakhira (in Arabic). pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b "Um Zayda Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. 2014-11-03. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Binebine, Ahmed-Chouqui (1992). Histoire des bibliothèques au Maroc (in French). Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines. p. 83.

- ^ a b Binebine, Ahmed-Chouqui (1992). Histoire des bibliothèques au Maroc. Faculté des lettres et des sciences humaines. p. 165.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bonsal, Stephen (1893). Morocco as it is: With an Account of Sir Charles Euan Smith's Recent Mission to Fez. Harper. pp. 59–60.

- ^ a b c d "LES HAREMS AU MAROC". dafina.net. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Miller, Susan Gilson (2013-04-15). A History of Modern Morocco. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-521-81070-8.

- ^ Pierre, Jean-Luc. "La mort du suLtan Hassan I er Le 7 juin 1894".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Archives marocaines: publication de la Mission scientifique du Maroc (in French). Librairie Ancienne Honoré Champion. 1906. p. 158.