Problem of evil

| Part of a series on |

| Theism |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Atheism |

|---|

| Part of a series on the |

| Philosophy of religion |

|---|

| Philosophy of religion article index |

In the philosophy of religion, the problem of evil is the question of how to reconcile the existence of evil with that of a God who is, in either absolute or relative terms, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent (see theism).[1][2] An argument from evil attempts to show that the co-existence of evil and such a God is unlikely or impossible if placed in absolute terms. Attempts to show the contrary have traditionally been discussed under the heading of theodicy.

A wide range of responses have been given to the problem of evil in theology. There are also many discussions of evil and associated problems in other philosophical fields, such as secular ethics,[3][4][5] and scientific disciplines such as evolutionary ethics.[6][7] But as usually understood, the "problem of evil" is posed in a theological context.[1][2]

Detailed arguments

Together, John Joseph Haldane's Wittgenstinian-Thomistic account of concept formation[8] and Martin Heidegger's observation of temporality's thrown nature[9] imply that God's act of creation and God's act of judgment are the same act. God's condemnation of evil is subsequently believed to be executed and expressed in his created world; a judgement that is unstoppable due to God's all powerful will; a constant and eternal judgement that becomes announced and communicated to other people on Judgment Day. In this explanation, God's condemnation of evil is declared to be a good judgement.

The above argument is set against numerous versions of the problem of evil that have been formulated.[1][2][10] These versions have included philosophical and theological formulations.

Logical problem of evil

The originator of the logical problem of evil has been cited as the Greek philosopher Epicurus,[11] and this argument may be schematized as follows:

- If an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent god exists, then evil does not.

- There is evil in the world.

- Therefore, an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent God does not exist.

This argument is of the form modus tollens, and is logically valid: If its premises are true, the conclusion follows of necessity. To show that the first premise is plausible, subsequent versions tend to expand on it, such as this modern example:[2]

- God exists.

- God is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent.

- An omnibenevolent being would want to prevent all evils.

- An omniscient being knows every way in which evils can come into existence, and knows every way in which those evils could be prevented.

- An omnipotent being has the power to prevent that evil from coming into existence.

- A being who knows every way in which an evil can come into existence, who is able to prevent that evil from coming into existence, and who wants to do so, would prevent the existence of that evil.

- If there exists an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent God, then no evil exists.

- Evil exists (logical contradiction).

Both of these arguments are understood to be presenting two forms of the logical problem of evil. They attempt to show that the assumed propositions lead to a logical contradiction and therefore cannot all be correct. Most philosophical debate has focused on the propositions stating that God cannot exist with, or would want to prevent, all evils (premises 3 and 6), with defenders of theism (for example, Leibniz) arguing that God could very well exist with and allow evil in order to achieve a greater good.

One greater good that has been proposed is that of free will, famously argued for by Alvin Plantinga in his free will defense. The first part of this defense accounts for moral evil as the result of free human action. The second part of this defense argues for the logical possibility of "a mighty nonhuman spirit"[12] such as Satan who is responsible for so-called "natural evils", including earthquakes, tidal waves, and virulent diseases. Some philosophers agree that Plantinga successfully solves the logical problem of evil, by showing that God and evil are logically compatible[13] though others explicitly dissent.[14][15] The second part of Plantinga's defense, though, concedes God's omnipotence by claiming the possibility of "a mighty nonhuman spirit" capable of causing evil in spite of God's desire for evil not to exist (a necessary consequence of His benevolence), effectively "overpowering" God.

Evidential problem of evil

The evidential version of the problem of evil (also referred to as the probabilistic or inductive version), seeks to show that the existence of evil, although logically consistent with the existence of God, counts against or lowers the probability of the truth of theism. As an example, a critic of Plantinga's idea of "a mighty nonhuman spirit" causing natural evils may concede that the existence of such a being is not logically impossible but argue that due to lacking scientific evidence for its existence this is very unlikely and thus it is an unconvincing explanation for the presence of natural evils. Both absolute versions and relative versions of the evidential problems of evil are presented below.

A version by William L. Rowe:

- There exist instances of intense suffering which an omnipotent, omniscient being could have prevented without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- An omniscient, wholly good being would prevent the occurrence of any intense suffering it could, unless it could not do so without thereby losing some greater good or permitting some evil equally bad or worse.

- (Therefore) There does not exist an omnipotent, omniscient, wholly good being.[2]

Another by Paul Draper:

- Gratuitous evils exist.

- The hypothesis of indifference, i.e., that if there are supernatural beings they are indifferent to gratuitous evils, is a better explanation for (1) than theism.

- Therefore, evidence prefers that no god, as commonly understood by theists, exists.[17]

These arguments are probability judgments since they rest on the claim that, even after careful reflection, one can see no good reason for God’s permission of evil. The inference from this claim to the general statement that there exists unnecessary evil is inductive in nature and it is this inductive step that sets the evidential argument apart from the logical argument.[2]

The logical possibility of hidden or unknown reasons for the existence of evil still exists. However, the existence of God is viewed as any large-scale hypothesis or explanatory theory that aims to make sense of some pertinent facts. The extent to which it fails to do so has not been confirmed.[2] According to Occam's razor, one should make as few assumptions as possible. Hidden reasons are assumptions, as is the assumption that all pertinent facts can be observed, or that facts and theories humans have not discerned are indeed hidden. Thus, as per Paul Draper's argument above, the theory that there is an omniscient and omnipotent being who is indifferent requires no hidden reasons in order to explain evil. It is thus a simpler theory than one that also requires hidden reasons regarding evil in order to include omnibenevolence. Similarly, for every hidden argument that completely or partially justifies observed evils it is equally likely that there is a hidden argument that actually makes the observed evils worse than they appear without hidden arguments. As such, from an inductive viewpoint hidden arguments will neutralize one another.[1]

Author and researcher Gregory S. Paul offers what he considers to be a particularly strong problem of evil. Paul introduces his own estimates that at least 100 billion people have been born throughout human history (starting roughly 50 000 years ago, when Homo Sapiens—humans—first appeared).[18] He then performed what he calls "simple" calculations to estimate the historical death rate of children throughout this time. He found that the historical death rate was over 50%, and that the deaths of these children were mostly due to diseases (like malaria).

Paul thus sees it as a problem of evil, because this means that within the bounds of his estimates, that throughout human history, over 50 billion people died naturally before they were old enough to give mature consent. He adds that as many as 300 billion humans may never have reached birth, instead dying naturally but prenatally (the prenatal death rate being about 3/4 historically). Paul says that these figures could have implications for calculating the population of a heaven (which could include the aforementioned 50 billion children, 50 billion adults, and roughly 300 billion fetuses—excluding any living today).[19][20]

A common response to instances of the evidential problem is that there are plausible (and not hidden) justifications for God’s permission of evil. These theodicies are discussed below.

Biblical examples

Though the purpose of the Bible from the church's perspective is to teach that God is all powerful and good, arguments from evil have examined biblical passages and have argued otherwise. By using examples from the Bible to claim that God is actually evil, the argument is made that this fact lowers the chance of actual theism or the existence of an all powerful and loving God.[22]

Genesis chapter 2 reads, "Out of the ground the Lord God made to grow every tree that is pleasant to the sight and good for food, the tree of life also in the midst of the garden, and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil."[23]

This section of Genesis introduces the "All Knowing Tree" that Adam and Eve eat from. Arguments from evil suggest that this is an example of God's evil nature or an example that shows that God isn't all powerful. The reasoning being that if God was all loving and powerful then the evil in the tree would not exist. Or it's possible that God isn't all powerful therefore He was not able to prohibit the evil in the tree.[24]

Regarding the story of Noah's Ark, Genesis chapter 6 reads, "I have determined to make an end of all flesh, for the earth is filled with violence because of them; now I am going to destroy them along with the earth."[25]

In this passage of the Bible one can see how God destroyed the earth, killing everyone in it, except Noah and his family. Arguments from evil often use this passage to demonstrate how God's wrath makes it impossible for him to be all loving and good.[21]

Related arguments

Doctrines of hell, particularly those involving eternal suffering, pose a particularly strong form of the problem of evil (see problem of hell). If the problem of unbelief, incorrect beliefs, or poor design are considered evils, then the argument from nonbelief, the argument from inconsistent revelations, and the argument from poor design may be seen as particular instances of the argument that the co-existence of evil with such a God is unlikely or impossible.

Responses, defences and theodicies

Responses to the problem of evil have occasionally been classified as defences or theodicies; however, authors disagree on the exact definitions.[1][2][26] Generally, a defense against the problem of evil may refer to attempts to defuse the logical problem of evil by showing that there is no logical incompatibility between the existence of evil and the existence of God. This task does not require the identification of a plausible explanation of evil, and is successful if the explanation provided shows that the existence of God and the existence of evil are logically compatible. It need not even be true, since a false though coherent explanation would be sufficient to show logical compatibility.[27]

A theodicy,[28] on the other hand, is more ambitious, since it attempts to provide a plausible justification—a morally or philosophically sufficient reason—for the existence of evil and thereby rebut the "evidential" argument from evil.[2] Richard Swinburne maintains that it does not make sense to assume there are greater goods that justify the evil's presence in the world unless we know what they are—without knowledge of what the greater goods could be, one cannot have a successful theodicy.[29] Thus, some authors see arguments appealing to demons or the fall of man as indeed logically possible, but not very plausible given our knowledge about the world, and so see those arguments as providing defences but not good theodicies.[2]

Denial of absolute omniscience, omnipotence, omnibenevolence

If God lacks any one of these qualities, the existence of evil is explicable, and so the problem of evil would be treated instead under the heading of some alternate formulation or doctrine of theology.

In polytheism the individual deities are usually not omnipotent or omnibenevolent as the powers which they share are distributed among the diverse gods; however, if one of the deities has these properties the problem of evil applies. Belief systems where several deities are omnipotent would lead to logical contradictions and conflict.

Ditheistic belief systems (a kind of dualism) explain the problem of evil from the existence of two rival great, but not omnipotent, deities that work in polar opposition to each other. Examples of such belief systems include Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, Catharism, and possibly Gnosticism. The Devil in Islam and in Christianity is not seen as equal in power to God who is omnipotent. Thus the Devil could only exist if so allowed by God. The Devil, if so limited in power, can therefore by himself not explain the problem of evil without recourse to theism or some alternate version of theology.

Process theology and open theism are other positions that limit God's omnipotence and/or omniscience (as defined in traditional Christian theology).

Denial of omnibenevolence

Dystheism is the belief that God is not wholly good. Pantheists and panentheists who are dystheistic may provide alternate versions for describing the disposition of evil.

"Greater good" responses

The omnipotence paradoxes, where evil persists in the presence of an all powerful God, raise questions as to the nature of God's omnipotence. Although that is from excluding the idea of how an interference would negate and subjugate the concept of free will, or in other words result in a totalitarian system that creates a lack of freedom. Some solutions propose that omnipotence does not require the ability to actualize the logically impossible. "Greater good" responses to the problem make use of this insight by arguing for the existence of goods of great value which God cannot actualize without also permitting evil, and thus that there are evils he cannot be expected to prevent despite being omnipotent. Among the most popular versions of the "greater good" response are appeals to the apologetics of free will. Theologians will argue that since no one can fully understand God's ultimate plan, no one can assume that evil actions do not have some sort of greater purpose. Therefore, the nature of evil has a necessary role to play in God's plan for a better world.[30]

Free will

Use of the term "free will" creates confusion unless its definition is stated.[31] In order to reduce confusion, Mortimer Adler found that a delineation of three kinds of freedom is necessary for clarity on the subject. ("Free will" and "freedom" are often used as synonyms.[32]) These three kinds of freedom follow:[33]

- "Circumstantial freedom" is "freedom from coercion or restraint" that prevents acting as one wills.[34]

- "Natural freedom" is freedom to will what one desires. This natural free will is inherent in all people.[35]

- "Acquired freedom" is freedom "to live as [one] ought." To possess acquired free will requires a change by which a person acquires a desire to live a life marked by qualities such as goodness and wisdom.[36]

For Greg Boyd, an open theist and exponent of libertarian freedom,[37] the free will response asserts that the existence of free beings is something of very high value, because with free will comes the ability to make morally significant choices (which include the expression of love and affection). Boyd also maintains that God does not plan or will evil in people's lives, but that evil is a result of a combination of free choices and the interconnectedness and complexity of life in a sinful and fallen world. With free will also comes the potential for ethical abuse, as when individuals fail to act morally. But the evil result created by such abuse of free will is easily outweighed by the great value of free will and the good that comes of it, and so God is justified in creating a world which offers the existence of free will, and with it the potential for evil. A world with free beings and no evil would be still better. However, this would require the cooperation of free beings with God, as it would be logically inconsistent for God to prevent abuses of freedom without thereby curtailing that freedom.[38]

However, critics of the free will response have questioned whether it accounts for the degree of evil seen in this world. One point in this regard is that while the value of free will may be thought sufficient to counterbalance minor evils, it is less obvious that it outweighs the negative attributes of evils such as rape and murder. Particularly egregious cases known as horrendous evils, which "[constitute] prima facie reason to doubt whether the participant’s life could (given their inclusion in it) be a great good to him/her on the whole," have been the focus of recent work in the problem of evil.[39] Another point is that those actions of free beings which bring about evil very often diminish the freedom of those who suffer the evil; for example the murder of a young child may prevent the child from ever exercising their free will. In such a case the freedom of an innocent child is pitted against the freedom of the evil-doer, it is not clear why God would remain unresponsive and passive.[40]

A second criticism is that the potential for evil inherent in free will may be limited by means which do not impinge on that free will. God could accomplish this by making moral actions especially pleasurable, so that they would be irresistible to us; he could also punish immoral actions immediately, and make it obvious that moral rectitude is in our self-interest; or he could allow bad moral decisions to be made, but intervene to prevent the harmful consequences from actually happening. A reply is that such a "toy world" would mean that free will has less or no real value.[41] Critics may respond that this view seems to imply it would be similarly wrong for humans to try to reduce suffering in these ways, a position which few would advocate.[42] It may nevertheless be advocated that the widescale prevention of suffering, such as with the indiscriminate use of analgesics, would lead individuals to become unresponsive to the rectifying feedback such suffering serves to provide. The debate depends on the definitions of free will and determinism, which are deeply disputed definitions, as well as their relation to one another. See also compatibilism, incompatibilism, and predestination. In general terms, compatibilism and incompatibilism refer to whether free-will in individuals is in conflict with a God who may or may not have knowledge of the outcome of the choices which individuals make based on this free-will before the choices are made.

A third reply is that though the free will defence has the potential to explain moral evil, it fails to address natural evil. By definition, moral evil results from human action, but natural evil results from natural processes that cause natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions or earthquakes.[43] Advocates of the free will response to evil propose various explanations of natural evils. Alvin Plantinga, following Augustine of Hippo,[44] and others have argued that natural evils are caused by the free choices of supernatural beings such as demons.[45] Others have argued

- • that natural evils are the result of the fall of man, which corrupted the perfect world created by God[46] or

- • that natural evils are the result of natural laws which are a prerequisite for the existence of intelligent free beings[47] or

- • that natural evils provide us with a knowledge of evil which makes our free choices more significant than they would otherwise be, and so our free will more valuable[48] or

- • that natural evils are a mechanism of divine punishment for moral evils that humans have committed, and so the natural evil is justified.[49] (See also Karma, just-world phenomenon, and original sin.)

Advocates of the free will response can also point to the fact that "the line between moral and natural evil is not always clear."[50] Natural evils are often caused or exacerbated by humans in their exercise of free will.[51]

- • "Deforestation and floodplain development" turn high rainfall into "devastating floods and mudslides."[52]

- • Earthquake casualties often result from poor construction.[53]

- • Dusty conditions in the American West that cause health problems are the "result of human activity and not part of the natural system."[54]

Finally, because the free will response assumes a libertarian account of free will, the debate over its adequacy naturally widens into a debate concerning the nature and existence of free will. Compatibilists deny that a being who is determined to act morally lacks free will, and so also believe that God cannot ensure the moral behavior of the free beings he creates. Hard determinists deny the existence of free will, and therefore they deny that the existence of free will justifies the evil in our world. There is also debate regarding the compatibility of moral free will (to select good or evil action) with the absence of evil from heaven,[55][56] with God's omniscience (see the argument from free will), and with his omnibenevolence.[10]

Soul-making or Irenaean theodicy

Distinctive of the soul-making theodicy is the claim that evil and suffering are necessary for spiritual growth. Theology consistent with this type of theodicy was developed by the second-century Christian theologian, Irenaeus of Lyons, and its most recent advocate has been the influential philosopher of religion, John Hick. A perceived inadequacy with the theodicy is that many evils do not seem to promote such growth, and can be positively destructive of the human spirit. Hick acknowledges that this process often fails in our world.[57] A second issue concerns the distribution of evils suffered: were it true that God permitted evil in order to facilitate spiritual growth, then we would expect evil to disproportionately befall those in poor spiritual health. This does not seem to be the case, as the decadent enjoy lives of luxury which insulate them from evil, whereas many of the pious are poor, and are well acquainted with worldly evils.[58] A third problem attending this theodicy is that the qualities developed through experience with evil seem to be useful precisely because they are useful in overcoming evil. But if there were no evil, then there would seem to be no value in such qualities, and consequently no need for God to permit evil in the first place. Against this it may be asserted that the qualities developed are intrinsically valuable, but this view would need further justification.

Afterlife

The afterlife has also been cited as justifying evil. Christian author Randy Alcorn argues that the joys of heaven will compensate for the sufferings on earth, and writes:

Without this eternal perspective, we assume that people who die young, who have handicaps, who suffer poor health, who don't get married or have children, or who don't do this or that will miss out on the best life has to offer. But the theology underlying these assumptions have a fatal flaw. It presumes that our present Earth, bodies, culture, relationships and lives are all there is... [but] Heaven will bring far more than compensation for our present sufferings.[59]

Philosopher Stephen Maitzen has called this the "Heaven Swamps Everything" theodicy, and argues that it is false because it conflates compensation and justification. He observes that this reasoning:

... may stem from imagining an ecstatic or forgiving state of mind on the part of the blissful: in heaven no one bears grudges, even the most horrific earthly suffering is as nothing compared to infinite bliss, all past wrongs are forgiven. But "are forgiven" doesn’t mean "were justified"; the blissful person’s disinclination to dwell on his or her earthly suffering doesn’t imply that a perfect being was justified in permitting the suffering all along. By the same token, our ordinary moral practice recognizes a legitimate complaint about child abuse even if, as adults, its victims should happen to be on drugs that make them uninterested in complaining. Even if heaven swamps everything, it doesn’t thereby justify everything.[60]

Previous lives and karma

The theory of karma holds that good acts result in pleasure and bad acts with suffering. Thus it accepts that there is suffering in the world, but maintains that there is no undeserved suffering, and in that sense, no evil. The obvious objection that people sometimes suffer misfortune that was undeserved is met with by coupling karma with reincarnation, so that such suffering is the result of actions in previous lifetimes.[61] The real problem of evil is the desire to invert the law of karma by way of causing suffering to the innocent, and rewarding pleasure to the guilty as superimposed rule.

Skeptical theism

Skeptical theists argue that due to humanity's limited knowledge, we cannot expect to understand God or his ultimate plan. When a parent takes an infant to the doctor for a regular vaccination to prevent childhood disease, it's because the parent cares for and loves that child. The infant however will be unable to appreciate this. It is argued that just as an infant cannot possibly understand the motives of its parent due to its cognitive limitations, so too are humans unable to comprehend God's will in their current physical and earthly state.[62] Given this view, the difficulty or impossibility of finding a plausible explanation for evil in a world created by God is to be expected, and so the argument from evil is assumed to fail unless it can be proven that God's reasons would be comprehensible to us.[63] A related response is that good and evil are strictly beyond human comprehension. Since our concepts of good and evil as instilled in us by God are only intended to facilitate ethical behaviour in our relations with other humans, we should have no expectation that our concepts are accurate beyond what is needed to fulfill this function, and therefore cannot presume that they are sufficient to determine whether what we call evil really is evil. Such a view may be independently attractive to the theist, as it permits an agreeable interpretation of certain biblical passages, such as "...Who makes peace and creates evil; I am the Lord, Who makes all these."[64]

Denial of the existence of evil

Evil as the absence of good (Privation Theory)

The fifth century theologian Augustine of Hippo maintained that evil exists only as a privation or absence of the good. Ignorance is an evil, but is merely the absence of knowledge, which is good; disease is the absence of health; callousness an absence of compassion. Since evil has no positive reality of its own, it cannot be caused to exist, and so God cannot be held responsible for causing it to exist. In its strongest form, this view may identify evil as an absence of God, who is the sole source of that which is good.

A related view, which draws on the Taoist concept of yin-yang, allows that both evil and good have positive reality, but maintains that they are complementary opposites, where the existence of each is dependent on the existence of the other. Compassion, a valuable virtue, can only exist if there is suffering; bravery only exists if we sometimes face danger; self-sacrifice is called for only where others are in need. This is sometimes called the "contrast" argument.[65]

Perhaps the most important criticism of this view is that, even granting its success against the argument from evil, it does nothing to undermine an 'argument from the absence of goodness' which may be pushed instead, and so the response is only superficially successful.[66][67]

Evil as illusory

It is possible to hold that evils such as suffering and disease are mere illusions, and that we are mistaken about the existence of evil. This approach is favored by some Eastern religious philosophies such as Hinduism and Buddhism, and by Christian Science. It is most plausible when considering our knowledge of evils which are geographically or temporally distant, for these might not be real after all. However, when considering our own sensations of pain and mental anguish, there does not seem to be a difference in apprehending that we are afflicted by such sensations and suffering under their influence. If that is the case, it seems that not all evils can be dismissed as illusory.[66][68]

Turning the tables

"Evil" suggests an ethical law

A different approach to the problem of evil is to turn the tables by suggesting that any argument from evil is self-refuting, in that its conclusion would necessitate the falsity of one of its premises. One response then is to point out that the assertion "evil exists" implies an ethical standard against which moral value is determined, and then to argue that this standard implies the existence of God (see argument from morality). C. S. Lewis writes:

My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?... Of course I could have given up my idea of justice by saying it was nothing but a private idea of my own. But if I did that, then my argument against God collapsed too—for the argument depended on saying the world was really unjust, not simply that it did not happen to please my fancies.[69]

The standard criticism of this view is that an argument from evil is not necessarily a presentation of the views of its proponent, but is instead intended to show how premises which the theist is inclined to believe lead him or her to the conclusion that God does not exist (i.e. as a reductio of the theist's worldview). Another tact is to reformulate the argument from evil so that this criticism does not apply—for example, by replacing the term "evil" with "suffering", or what is more cumbersome, state of affairs that orthodox theists would agree are properly called "evil".[70]

General criticisms of defenses and theodicies

Several philosophers[71][72] have argued that just as there exists a problem of evil for theists who believe in an omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent being, so too is there a problem of good for anyone who believes in an omniscient, omnipotent, and omnimalevolent (or perfectly evil) being. As it appears that the defenses and theodicies which might allow the theist to resist the problem of evil can be inverted and used to defend belief in the omnimalevolent being, this suggests that we should draw similar conclusions about the success of these defensive strategies. In that case, the theist appears to face a dilemma: either to accept that both sets of responses are equally bad, and so that the theist does not have an adequate response to the problem of evil; or to accept that both sets of responses are equally good, and so to commit to the existence of an omnipotent, omniscient, and omnimalevolent being as plausible. Critics have noted that theodicies and defenses are often addressed to the logical problem of evil. As such, they are intended only to demonstrate that it is possible that evil can co-exist with an omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent being. Since the relevant parallel commitment is only that good can co-exist with an omniscient, omnipotent and omnimalevolent being, not that it is plausible that they should do so, the theist who is responding to the problem of evil need not be committing himself to something he is likely to think is false.[73] This reply, however, leaves the evidential problem of evil untouched.

Another general criticism is that though a theodicy may harmonize God with the existence of evil, it does so at the cost of nullifying morality. This is because most theodicies assume that whatever evil there is exists because it is required for the sake of some greater good. But if an evil is necessary because it secures a greater good, then it appears we humans have no duty to prevent it, for in doing so we would also prevent the greater good for which the evil is required. Even worse, it seems that any action can be rationalized, as if one succeeds in performing it, then God has permitted it, and so it must be for the greater good. From this line of thought one may conclude that, as these conclusions violate our basic moral intuitions, no greater good theodicy is true, and God does not exist. Alternatively, one may point out that greater good theodicies lead us to see every conceivable state of affairs as compatible with the existence of God, and in that case the notion of God's goodness is rendered meaningless.[74][75][76][77]

See also Christian alternatives to theodicy.

By religion

Ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt

The problem of evil takes at least four formulations in ancient Mesopotamian religious thought, as in the extant manuscripts of Ludlul bēl nēmeqi (I Will Praise the Lord of Wisdom), Erra and Ishum, The Babylonian Theodicy, and The Dialogue of Pessimism. In this type of polytheistic context, the chaotic nature of the world implies multiple gods battling for control.

In ancient Egypt, it was thought the problem takes at least two formulations, as in the extant manuscripts of Dialogue of a Man with His Ba and The Eloquent Peasant. Due to the conception of Egyptian gods as being far removed, these two formulations of the problem focus heavily on the relation between evil and people; that is, moral evil.[78]

Judaism

An oral tradition exists in Judaism that God determined the time of the Messiah's coming by erecting a great set of scales. On one side, God placed the captive Messiah with the souls of dead laymen. On the other side, God placed sorrow, tears, and the souls of righteous martyrs. God then declared that the Messiah would appear on earth when the scale was balanced. According to this tradition, then, evil is necessary in the bringing of the world's redemption, as sufferings reside on the scale.[citation needed]

The Talmud states that every bad thing is for the ultimate good, and a person should praise God for bad things like he praises God for the good things.[citation needed]

Tzimtzum in Kabbalistic thought holds that God has withdrawn himself so that creation could exist, but that this withdrawal means that creation lacks full exposure to God's all-good nature.[citation needed]

Christianity

The Bible

The Bible "has been, both in theory and in fact, the dominant influence upon ideas about God and evil in the Western world."[79] The word "evil" occurs 613 times in the King James Version of the Bible:[80] 481 times in the Old Testament[81] and 132 times in the New Testament.[82]

In the biblical view, evil is all that is "opposed to God and His purposes" (i.e., sin) or that which, from the human perspective, is "harmful and nonproductive" (i.e., suffering).[83]

The existence of evil creates not only a problem for existence, but also for belief in an all-good and all-powerful God,[84] because if God were all-good and all-powerful then in theory such a God would be able to prohibit such evils from happening.[30] In response, theologians have argued that though the problem of evil is present, it alone is not strong enough evidence to suggest that God is not all powerful and loving.[30] Two reasons have been put forth to explain why God has good reasons to permit such evils, the greater good response and the free will response. Greater good responses explain that God allows evil acts in the world because they are part of God's plan and will teach the world a moral value.[30] The free will response, on the other hand, argues that if God prohibited evil, he would be interfering with free will and the natural laws of the world.[30]

Gnosticism

Gnosticism refers to several beliefs seeing evil as due to the world being created by an imperfect God, the demiurge, which is contrasted with a superior entity. However, this by itself does not answer the problem of evil if the superior entity is omnipotent and omnibenevolent. Different gnostic beliefs may give varying answers, like Manichaeism, which adopts dualism, in opposition to the doctrine of omnipotence.

Irenaean theodicy

Irenaean theodicy, posited by Irenaeus (2nd century AD–c. 202), has been reformulated by John Hick. It holds that one cannot achieve moral goodness or love for God if there is no evil and suffering in the world. Evil is soul-making and leads one to be truly moral and close to God. God created an epistemic distance (such that God is not immediately knowable) so that we may strive to know him and by doing so become truly good. Evil is a means to good for 3 main reasons:

- Means of knowledge – Hunger leads to pain, and causes a desire to feed. Knowledge of pain prompts humans to seek to help others in pain.

- Character building – Evil offers the opportunity to grow morally. "We would never learn the art of goodness in a world designed as a hedonistic paradise" (Richard Swinburne)

- Predictable environment – The world runs to a series of natural laws. These are independent of any inhabitants of the universe. Natural Evil only occurs when these natural laws conflict with our own perceived needs. This is not immoral in any way

Pelagianism

The consequences of the original sin were debated by Pelagius and Augustine of Hippo. Pelagius argues on behalf of original innocence, while Augustine indicts Eve and Adam for original sin. Pelagianism is the belief that original sin did not taint all of humanity and that mortal free will is capable of choosing good or evil without divine aid. Augustine's position, and subsequently that of much of Christianity, was that Adam and Eve had the power to topple God's perfect order, thus changing nature by bringing sin into the world, but that the advent of sin then limited mankind's power thereafter to evade the consequences without divine aid.[85] Eastern Orthodox theology holds that one inherits the nature of sinfulness but not Adam and Eve's guilt for their sin which resulted in the fall.[86]

Augustinian theodicy

St Augustine of Hippo (AD 354–430) in his Augustinian theodicy, as presented in John Hick's book Evil and the God of Love, focuses on the Genesis story that essentially dictates that God created the world and that it was good; evil is merely a consequence of the fall of man (The story of the Garden of Eden where Adam and Eve disobeyed God and caused inherent sin for man). Augustine stated that natural evil (evil present in the natural world such as natural disasters etc.) is caused by fallen angels, whereas moral evil (evil caused by the will of human beings) is as a result of man having become estranged from God and choosing to deviate from his chosen path. Augustine argued that God could not have created evil in the world, as it was created good, and that all notions of evil are simply a deviation or privation of goodness. Evil cannot be a separate and unique substance. For example, Blindness is not a separate entity, but is merely a lack or privation of sight. Thus the Augustinian theodicist would argue that the problem of evil and suffering is void because God did not create evil; it was man who chose to deviate from the path of perfect goodness.

St. Thomas Aquinas

Saint Thomas systematized the Augustinian conception of evil, supplementing it with his own musings. Evil, according to St. Thomas, is a privation, or the absence of some good which belongs properly to the nature of the creature.[87] There is therefore no positive source of evil, corresponding to the greater good, which is God;[88] evil being not real but rational—i.e. it exists not as an objective fact, but as a subjective conception; things are evil not in themselves, but by reason of their relation to other things or persons. All realities are in themselves good; they produce bad results only incidentally; and consequently the ultimate cause of evil is fundamentally good, as well as the objects in which evil is found.[89]

Catholic Encyclopedia

Evil is threefold, viz., metaphysical evil, moral, and physical, the retributive consequence of moral guilt. Its existence subserves the perfection of the whole; the universe would be less perfect if it contained no evil. Thus fire could not exist without the corruption of what it consumes; the lion must slay the ass in order to live, and if there were no wrong doing, there would be no sphere for patience and justice. God is said (as in Isaiah 45) to be the author of evil in the sense that the corruption of material objects in nature is ordained by Him, as a means for carrying out the design of the universe; and on the other hand, the evil which exists as a consequence of the breach of Divine laws is in the same sense due to Divine appointment; the universe would be less perfect if its laws could be broken with impunity. Thus evil, in one aspect, i.e. as counter-balancing the deordination of sin, has the nature of good. But the evil of sin, though permitted by God, is in no sense due to him; denying the Divine omnipotence, that another equally perfect universe could not be created in which evil would have no place.[90]

Luther and Calvin

Both Luther and Calvin explained evil as a consequence of the fall of man and the original sin. However, due to the belief in predestination and omnipotence, the fall is part of God's plan. Ultimately humans may not be able to understand and explain this plan.[91]

Calvin also concluded:[92]

Book II. chap. i . . . Therefore, original sin is seen to be an hereditary depravity and corruption of our nature diffused into all parts of the soul . . . wherefore those who have defined original sin as the lack of the original righteousness with which we should have been endowed, no doubt include, by implication, the whole fact of the matter, but they have not fully expressed the positive energy of this sin. For our nature is not merely bereft of good, but is so productive of every kind of evil that it cannot be inactive. Those who have called it concupiscence [a strong, especially sexual desire, lust] have used a word by no means wide of the mark, if it were added (and this is what many do not concede) that whatever is in man from intellect to will, from the soul to the flesh, is all defiled and crammed with concupiscence; or, to sum it up briefly, that the whole man is in himself nothing but concupiscence. . . .

Chap. iv . . . . The old writers often shrink from the straightforward acknowledgement of the truth in this matter, from motives of piety. They are afraid of opening to the blasphemers a widow for their slanders concerning the works of God. While I salute their restraint, I consider that there is very little danger of this if we simply hold to the teaching of Scripture. Even Augustine is not always emancipated from that superstitious fear; as when he says (Of Predestination and Grace, §§ 4. 5) that ‘hardening’ and ‘blinding’ refer not to the operation of God, but to his foreknowledge. But there are so many sayings of Scripture, which will not admit of such fine distinctions; for they clearly indicate that God’s intervention consists in something more than his fore knowledge. . . . In the same way their suggestions as to God's ‘permission.’ are too weak to stand. It is very often said that God blinded and hardened the reprobate, that he turned, inclined, or drove on their hearts . . . . And no explanation of such statements is given by taking refuge in ‘foreknowledge’ or ‘permission.’ We therefore reply that this [process of hardening and blinding] comes about in two ways: When his light is removed, nothing remains but darkness and blindness when his Spirit is taken away, our hearts harden into stone; when his guidance ceases, we are turned from the straight path. And so he is rightly said to blind, to harden, to turn, those from whom he takes away the ability to see, to obey, to keep on the straight path. But the second way is much nearer the proper meaning of the words; that to carry out his judgments he directs their councils and excites their wills, in the direction which he has decided upon, through the agency of Satan, the minister of his wrath . . . .

Book III. Chap. xxi. No one who wishes to be thought religious dares outright to deny predestination by which God chooses some for the hope of life, and condemns others to eternal death. But men entangle it with captious quibbles; and especially those who make foreknowledge the ground of it. We indeed attribute to God both predestination and foreknowledge; but we call it absurd to subordinate one to the other. When we attribute foreknowledge to God we mean that all things have ever been, and eternally remain, before his eyes; to that to his knowledge nothing is future or past, but all things are present; and present not in the sense that they are reproduced in imagination (as we are aware of past events which are retained in our memory), but present in the sense that he really sees and observes them placed, as it were, before his eyes. And this foreknowledge extends over the whole universe and over every creature. By predestination we mean the eternal decree of God, by which he has decided in his own mind what he wishes to happen in the case of each individual. For all men are not created on an equal footing, but for some eternal life is pre‑ordained, for others eternal damnation. . . . .

Christian Science

Christian Science views evil as having no ultimate reality and as being due to false beliefs, consciously or unconsciously held. Evils such as illness and death may be banished by correct understanding. This view has been questioned, aside from the general criticisms of the concept of evil as an illusion discussed earlier, since the presumably correct understanding by Christian Science members, including the founder, has not prevented illness and death.[68] However, Christian Scientists believe that the many instances of spiritual healing (as recounted e.g. in the Christian Science periodicals and in the textbook Science and Health with Key to the Scriptures by Mary Baker Eddy) are anecdotal evidence of the correctness of the teaching of the unreality of evil.[93] According to one author, the denial by Christian Scientists that evil ultimately exists neatly solves the problem of evil; however, most people cannot accept that solution[94]

Jehovah's Witnesses

Jehovah's Witnesses believe that Satan is the original cause of evil.[95] Though once a perfect angel, Satan developed feelings of self-importance and craved worship, and eventually challenged God's right to rule. Satan caused Adam and Eve to disobey God, and humanity subsequently became participants in a challenge involving the competing claims of Jehovah and Satan to universal sovereignty.[96] Other angels who sided with Satan became demons.

God's subsequent tolerance of evil is explained in part by the value of free will. But Jehovah's Witnesses also hold that this period of suffering is one of non-interference from God, which serves to demonstrate that Jehovah's "right to rule" is both correct and in the best interests of all intelligent beings, settling the "issue of universal sovereignty". Further, it gives individual humans the opportunity to show their willingness to submit to God's rulership.

At some future time known to him, God will consider his right to universal sovereignty to have been settled for all time. The reconciliation of "faithful" humankind will have been accomplished through Christ, and nonconforming humans and demons will have been destroyed. Thereafter, evil (any failure to submit to God's rulership) will be summarily executed.[97][98]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) introduces a concept similar to Irenaean theodicy, that experiencing evil is a necessary part of the development of the soul. Specifically, the laws of nature prevent an individual from fully comprehending or experiencing good without experiencing its opposite.[99] In this respect, Latter-day Saints do not regard the fall of Adam and Eve as a tragic, unplanned cancellation of an eternal paradise; rather they see it as an essential element of God's plan. By allowing opposition and temptations in mortality, God created an environment for people to learn, to develop their freedom to choose, and to appreciate and understand the light, with a comparison to darkness [100][101]

This is a departure from the mainstream Christian definition of omnipotence and omniscience, which Mormons believe was changed by post-apostolic theologians in the centuries after Christ. The writings of Justin Martyr, Origen, Augustine, and others indicate a merging of Christian principles with Greek metaphysical philosophies such as Neoplatonism, which described divinity as an utterly simple, immaterial, formless substance/essence (ousia) that was the absolute causality and creative source of all that existed.[102] Mormons teach that through modern day revelation, God restored the truth about his nature, which eliminated the speculative metaphysical elements that had been incorporated after the Apostolic era.[103] As such, God's omniscience/omnipotence is not to be understood as metaphysically transcending all limits of nature, but as a perfect comprehension of all things within nature[104]—which gives God the power to bring about any state or condition within those bounds.[105] This restoration also clarified that God does not create Ex nihilo (out of nothing), but uses existing materials to organize order out of chaos.[106] Because opposition is inherent in nature, and God operates within nature’s bounds, God is therefore not considered the author of evil, nor will He eradicate all evil from the mortal experience.[107] His primary purpose, however, is to help His children to learn for themselves to both appreciate and choose the right, and thus achieve eternal joy and live in his presence, and where evil has no place.[100][108]

Islam

Islamic scholar Sherman Jackson states that the Mu'tazila school emphasized God's omnibenevolence. Evil arises not from God but from the actions of his creations who create their own actions independent of God. The Ash'ari school instead emphasized God's omnipotence. God is not restricted to follow some objective moral system centered on humans but has the power do whatever he wants with his world. The Maturidi school argued that evil arises from God but that evil in the end has a wiser purpose as a whole and for the future. Some theologians have viewed God as all-powerful and human life as being between the hope that God will be merciful and the fear that he will not.[109]

Hinduism

Hinduism is a complex religion with many different currents or schools. As such the problem of evil in Hinduism is answered in several different ways such as by the concept of karma.

Buddhism

In Buddhism, the problem of evil, or the related problem of dukkha, is one argument against a benevolent, omnipotent creator god, identifying such a notion as attachment to a false concept.[110]

Pandeism

While acknowledging that William L. Rowe had raised "a powerful, evidential argument against ethical theism," theologian William C. Lane contends that the theological theory of pandeism escapes the problem of evil. Lane writes of Rowe's proof:

However, it does not count against pandeism. In pandeism, God is no superintending, heavenly power, capable of hourly intervention into earthly affairs. No longer existing "above," God cannot intervene from above and cannot be blamed for failing to do so. Instead God bears all suffering, whether the fawn's or anyone else's. Even so, a skeptic might ask, "Why must there be so much suffering,? Why could not the world's design omit or modify the events that cause it?" In pandeism, the reason is clear: to remain unified, a world must convey information through transactions. Reliable conveyance requires relatively simple, uniform laws. Laws designed to skip around suffering-causing events or to alter their natural consequences (i.e., their consequences under simple laws) would need to be vastly complicated or (equivalently) to contain numerous exceptions. Such laws would not be discernable from within the world. From that standpoint, the only one that matters, they would not be laws at all. Absent laws, transactions would not reliably convey information, and the world could not be one. God could not consistently become such a world.[111]: 76–77

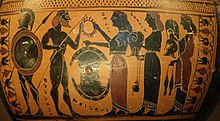

Greek mythology

The gods in Greek mythology were seen as superior, but shared similar traits with humans and often interacted with them.[112] Although the Greeks didn't believe in any "evil" gods, the Greeks still acknowledged the fact that evil was present in the world.[113] Gods often meddled in the affairs of men, and sometimes their actions consisted of bringing misery to people, for example gods would sometimes be a direct cause of death for people.[112] However, the Greeks did not consider the gods to be evil as a result of their actions, instead the answer for most situations in Greek mythology was the power of fate.[114] Fate is considered to be more powerful than the gods themselves and for this reason no one can escape it.[114] For this reason the Greeks recognized that unfortunate events were justifiable by the idea of fate.[114]

By philosophers

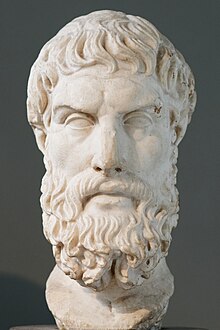

Epicurus

Epicurus is generally credited with first expounding the problem of evil, and it is sometimes called the "Epicurean paradox", the "riddle of Epicurus", or the "Epicurian trilemma":

"Is God willing to prevent evil, but not able? Then he is not omnipotent. Is he able, but not willing? Then he is malevolent. Is he both able and willing? Then whence cometh evil? Is he neither able nor willing? Then why call him God?" — 'the Epicurean paradox'.[115]

Epicurus himself did not leave any written form of this argument. It can be found in Christian theologian Lactantius's Treatise on the Anger of God[n 1] where Lactantius critiques the argument. Epicurus's argument as presented by Lactantius actually argues that a god that is all-powerful and all-good does not exist and that the gods are distant and uninvolved with man's concerns. The gods are neither our friends nor enemies.

David Hume

David Hume's formulation of the problem of evil in Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion:

"Is he [God] willing to prevent evil, but not able? then is he impotent. Is he able, but not willing? then is he malevolent. Is he both able and willing? whence then is evil?"[118]

"[God's] power we allow [is] infinite: Whatever he wills is executed: But neither man nor any other animal are happy: Therefore he does not will their happiness. His wisdom is infinite: He is never mistaken in choosing the means to any end: But the course of nature tends not to human or animal felicity: Therefore it is not established for that purpose. Through the whole compass of human knowledge, there are no inferences more certain and infallible than these. In what respect, then, do his benevolence and mercy resemble the benevolence and mercy of men?"

Gottfried Leibniz

In his Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, the sceptic Pierre Bayle denied the goodness and omnipotence of God on account of the sufferings experienced in this earthly life. Gottfried Leibniz introduced the term theodicy in his 1710 work Essais de Théodicée sur la bonté de Dieu, la liberté de l'homme et l'origine du mal ("Theodicic Essays on the Benevolence of God, the Free will of man, and the Origin of Evil") which was directed mainly against Bayle. He argued that this is the best of all possible worlds that God could have created.

Imitating the example of Leibniz, other philosophers also called their treatises on the problem of evil theodicies. Voltaire's popular novel Candide mocked Leibnizian optimism through the fictional tale of a naive youth.

Thomas Robert Malthus

The population and economic theorist Thomas Malthus argued in a 1798 essay that evil exists to spur human creativity and production. Without evil or the necessity of strife mankind would have remained in a savage state since all amenities would be provided for.[119]

Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant argued for sceptical theism. He claimed there is a reason all possible theodicies must fail: evil is a personal challenge to every human being and can be overcome only by faith.[120] He wrote:[121]

We can understand the necessary limits of our reflections on the subjects which are beyond our reach. This can easily be demonstrated and will put an end once and for all to the trial.

Victor Cousin

Victor Cousin (1856) stridently argued that different competing philosophical ideologies all had some claim on truth, as they all had arisen in defense of some truth. He however argued that there was a theodicy which united them, and that one should be free in quoting competing and sometimes contradictory ideologies in order to gain a greater understanding of truth through their reconciliation.[122]

Peter Kreeft

Christian philosopher Peter Kreeft provides several answers to the problem of evil and suffering, including that a) God may use short-term evils for long-range goods, b) God created the possibility of evil, but not the evil itself, and that free will was necessary for the highest good of real love. Kreeft says that being all-powerful doesn't mean being able to do what is logically contradictory, e.g., giving freedom with no potentiality for sin, c) God's own suffering and death on the cross brought about his supreme triumph over the devil, d) God uses suffering to bring about moral character, quoting apostle Paul in Romans 5, e) Suffering can bring people closer to God, and f) The ultimate "answer" to suffering is Jesus himself, who, more than any explanation, is our real need.[123]

William Hatcher

Mathematical logician William Hatcher (a member of the Baha'i Faith) made use of relational logic to claim that very simple models of moral value cannot be consistent with the premise of evil as an absolute, whereas goodness as an absolute is entirely consistent with the other postulates concerning moral value.[124] In Hatcher's view, one can only validly say that if an act A is "less good" than an act B, one cannot logically commit to saying that A is absolutely evil, unless that one is prepared to abandon other more reasonable principles.

See also

Notes and references

- Notes

- ^

Quod si haec ratio vera est, quam stoici nullo modo videre potuerunt, dissolvitur etiam argumentum illud Epicuri. Deus, inquit, aut vult tollere mala et non potest; aut potest et non vult; aut neque vult, neque potest; aut et vult et potest. Si vult et non potest, imbecillis est; quod in Deum non cadit. Si potest et non vult, invidus; quod aeque alienum a Deo. Si neque vult, neque potest, et invidus et imbecillis est; ideoque neque Deus. Si vult et potest, quod solum Deo convenit, unde ergo sunt mala? aut cur illa non tollit? Scio plerosque philosophorum, qui providentiam defendunt, hoc argumento perturbari solere et invitos pene adigi, ut Deum nihil curare fateantur, quod maxime quaerit Epicurus.

— Lactantius, De Ira Dei[116]But if this account is true, which the Stoics were in no manner able to see, that argument also of Epicurus is done away. God, he says, either wishes to take away evils, and is unable; or He is able and is unwilling; or He is neither willing nor able, or He is both willing and able. If He is willing and is unable, He is feeble, which is not in accordance with the character of God; if He is able and unwilling, He is envious, which is equally at variance with God; if He is neither willing or able, He is both envious and feeble, and therefore not God; if He is both willing and able, which alone is suitable to God, from what source then are evils or why does He not remove them? I know that many of the philosophers, who defend providence, are accustomed to be disturbed by this argument, and are almost driven against their will to admit that God takes no interest in anything, which Epicurus especially aims at.

— Lactantius, On the Anger of God[117]

- References

- ^ a b c d e The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Problem of Evil", Michael Tooley

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Evidential Problem of Evil", Nick Trakakis

- ^ Nicholas J. Rengger, Moral Evil and International Relations, in SAIS Review 25:1, Winter/Spring 2005, pp. 3–16

- ^ Peter Kivy, Melville's Billy and the Secular Problem of Evil: the Worm in the Bud, in The Monist (1980), 63

- ^ Kekes, John (1990). Facing Evil. Princeton: Princeton UP. ISBN 0-691-07370-8.

- ^ Timothy Anders, The Evolution of Evil (2000)

- ^ J.D. Duntley and David Buss, "The Evolution of Evil," in Miller, Arthur (2004). The Social Psychology of Good and Evil (PDF). New York: Guilford. pp. 102–133. ISBN 1-57230-989-X.

- ^ J.J. Haldane Atheism & Theism,(Second Edition, 2003) pp 102-105

- ^ Heidegger, Martin, Being and Time, Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson, 1962, reprint 2003, Blackwell Oxford UK & Cambridge USA, pp426-427 (H 374) and pp458-472 (H406-421)

- ^ a b The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Logical Problem of Evil", James R. Beebe

- ^ The formulation may have been wrongly attributed to Epicurus by Lactantius, who, from his Christian perspective, regarded Epicurus as an atheist. According to Mark Joseph Larrimore, (2001), The Problem of Evil, pp. xix–xxi. Wiley-Blackwell. According to Reinhold F. Glei, it is settled that the argument of theodicy is from an academical source which is not only not epicurean, but even anti-epicurean. Reinhold F. Glei, Et invidus et inbecillus. Das angebliche Epikurfragment bei Laktanz, De ira dei 13,20–21, in: Vigiliae Christianae 42 (1988), p. 47–58

- ^ Plantinga, Alvin (1974). God, Freedom, and Evil. Harper & Row. p. 58. ISBN 0-8028-1731-9.

- ^ Meister, Chad (2009). Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Routledge. p. 134. ISBN 0-415-40327-8.

- ^ Sobel, J.H. Logic and Theism. Cambridge University Press (2004) pp. 436-7

- ^ For example, the compatibility of God's omniscience and free will has been questioned (see the Argument from free will).

- ^ Rowe, William L. (1979). "The Problem of Evil and Some Varieties of Atheism". American Philosophical Quarterly. 16: 337.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Draper, Paul (1989). "Pain and Pleasure: An Evidential Problem for Theists". Noûs. 23 (3). Noûs, Vol. 23, No. 3: 331–350. doi:10.2307/2215486. JSTOR 2215486.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Haub, C. 1995/2004. "How Many People Have Ever Lived On Earth?" Population Today, http://www.prb.org/Articles/2002/HowManyPeopleHaveEverLivedonEarth.aspx

- ^ Paul, G.S. (2009) "Theodicy’s Problem: A Statistical Look at the Holocaust of the Children and the Implications of Natural Evil For the Free Will and Best of All Possible Worlds Hypotheses" Philosophy & Theology 19:125–149

- ^ Greg Paul and the Problem of Evil, on the podcast and TV show "The Atheist Experience", http://www.atheist-experience.com/

- ^ a b Dynes, Russell. "Noah And Disaster Planning". Academic Search Premier. Academic Search Premier. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Almeida, Michael. "The Logical Problem Of Evil Regained". Academic Search Premier. Academic Search Premier. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ "Genesis Two". BibleGateway. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Slivniak, Dmitri. "The Garden Of Double Messages". Academic Search Premier. Academic Search Premier. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

- ^ "Genesis Six". BibleGateway. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ Honderich, Ted (2005). "theodicy". The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. ISBN 0-19-926479-1.

John Hick, for example, proposes a theodicy, while Alvin Plantinga formulates a defence. The idea of human free will often appears in a both of these strategies, but in different ways.

- ^ For more explanation regarding contradictory propositions and possible worlds, see Plantinga's "God, Freedom and Evil" (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans 1974), 24–29.

- ^ Coined by Leibniz from Greek θεός (theós), "god" and δίκη (díkē), "justice", may refer to the project of "justifying God" – showing that God's existence is compatible with the existence of evil.

- ^ Swinburne, Richard (2005). "evil, the problem of". In Ted Honderich (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. ISBN 0-19-926479-1.

- ^ a b c d e Whitney, B. "Theodicy". Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Randy Alcorn, If God Is Good: Faith in the Midst of Suffering and Evil (Multnomah Books, 2009), 243.

- ^ Ted Honderich, "Determinism and Freedom Philosophy – Its Terminology," http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~uctytho/dfwTerminology.html (accessed 7 November 2009).

- ^ Mortimer J. Adler, The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom, Vol 1 (Doubleday, 1958).

- ^ Mortimer J. Adler, The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom, Vol 1 (Doubleday, 1958), 127.

- ^ Mortimer J. Adler, The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom, Vol 1 (Doubleday, 1958), 149.

- ^ Mortimer J. Adler, The Idea of Freedom: A Dialectical Examination of the Idea of Freedom, Vol 1 (Doubleday, 1958), 135.

- ^ http://reknew.org/2007/12/is-free-will-compatible-with-predestination/. "Libertarian freedom is not compatible with predestination, it is compatible with Scripture." Accessed 14 July 2014.

- ^ Gregory A. Boyd, Is God to Blame? (InterVarsity Press, 2003) 57-58, 76, 96.

- ^ Marilyn McCord Adams, Horrendous Evils and the Goodness of God (Cornell University, 2000), 203.

- ^ Marilyn McCord Adams, Horrendous Evils and the Goodness of God (Melbourne University Press, 1999), 26.

- ^ C. S. Lewis writes: "We can, perhaps, conceive of a world in which God corrected the results of this abuse of free will by His creatures at every moment: so that a wooden beam became soft as grass when it was used as a weapon, and the air refused to obey me if I attempted to set up in it the sound waves that carry lies or insults. But such a world would be one in which wrong actions were impossible, and in which, therefore, freedom of the will would be void; nay, if the principle were carried out to its logical conclusion, evil thoughts would be impossible, for the cerebral matter which we use in thinking would refuse its task when we attempted to frame them." C.S. Lewis The Problem of Pain (HarperCollins, 1996) pp. 24–25

- ^ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, s.v. "The Problem of Evil," Michael Tooley at http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/evil/.

- ^ "The Two Types of Evil," at http://www.bbc.co.uk/schools/gcsebitesize/rs/god/chgoodandevilrev1.shtml. Accessed 10 July 2014.

- ^ Alvin Plantinga, God, Freedom, and Evil (Eerdmans, 1989), 58.

- ^ Bradley Hanson, Introduction to Christian Theology (Fortress, 1997), 99.

- ^ Linda Edwards, A Brief Guide (Westminster John Knox, 2001), 62.

- ^ John Polkinghorne is one advocate of the view that the current natural laws are necessary for free will Polkinghorne, John (2003). Belief in God in an Age of Science. New Haven, CT: Yale Nota Bene. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-300-09949-2. and also See esp. ch. 5 of his Science and Providence. ISBN 978-0-87773-490-1

- ^ Richard Swinburne in "Is There a God?" writes that "the operation of natural laws producing evils gives humans knowledge (if they choose to seek it) of how to bring about such evils themselves. Observing you can catch some disease by the operation of natural processes gives me the power either to use those processes to give that disease to other people, or through negligence to allow others to catch it, or to take measures to prevent others from catching the disease." In this way, "it increases the range of significant choice... The actions which natural evil makes possible are ones which allow us to perform at our best and interact with our fellows at the deepest level" (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996) 108–109.

- ^ Bradley Hanson, Introduction to Christian Theology (Fortress, 1997), 100.

- ^ Bradley Hanson, Introduction to Christian Theology (Fortress, 1997), 98.

- ^ Dennis S. Mileti, Disasters by Design: a Reassessment of Natural Hazards in the United States (Joseph Henry Press, 1999).

- ^ "Natural Disasters Made Worse by Human Activity" (20 May 2008), http://www.expatica.com/fr/news/local_news/Natural-disasters-made-worse-by-human-activity-_43194.html#. Accessed 2 December 2009.

- ^ "UN Says Poor Construction to Blame for Earthquake Deaths", 19 May 2008, http://www.expatica.com/fr/news/local_news/UN-says-poor-construction-to-blame-for-earthquake-deaths-_43155.html (access 2 December 2009).

- ^ "Dust in West up 500 Percent in Past 2 Centuries, says CU-Boulder Study," http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2008-02/uoca-diw022208.php (accessed 2 December 2009).

- ^ Oppy, Graham. Arguing about Gods, pp. 314–39. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521863864

- ^ Simon Cushing (2010). "Evil, Freedom and the Heaven Dilemma" (PDF). Challenging Evil: Time, Society and Changing Concepts of the Meaning of Evil. Inter-Disciplinary Press. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ John Hick, Evil and the God of Love , (Palgrave Macmillan, 2nd edition 1977, 2010 reissue), 325, 336.

- ^ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "The Problem of Evil", James R. Beebe

- ^ If God Is Good: Faith in the Midst of Suffering and Evil, published by Random House of Canada, 2009, page 294

- ^ "Ordinary Morality Implies Atheism", European Journal for Philosophy of Religion 1:2 (2009), 107-126

- ^ Kaufman, WRP: Karma, Rebirth, And the Problem of Evil.

- ^ Wayne Blank. "Daily Bible Study - Why Does God Allow Suffering?". Keyway.ca. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ The Supposed Problem of Evil, biblicalstudies.org/journal/v006n01.html

- ^ "Yeshayahu - Chapter 45 - Tanakh Online - Torah - Bible". Chabad.org. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Westphal, Jonathan. "Response to Ethics Question". Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Does Evil Exist?". philosophyofreligion.info. 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Sobel, J.H. Logic and Theism. Cambridge University Press (2004) pp. 438.

- ^ a b Millard J. Erickson, Christian Theology, Second Edition, Baker Academic, 2007, pp. 445-446.

- ^ C. S. Lewis Mere Christianity Touchstone:New York, 1980 pp. 45–46

- ^ Oppy, Graham. Arguing about Gods, pp. 261. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521863864

- ^ [1] Cahn, Stephen M. (1977). Cacodaemony. Analysis, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 69-73.

- ^ [2] Law, Stephen (2010). The Evil-God Challenge. Religious Studies 46 (3):353-373

- ^ Cacodaemony and Devilish Isomorphism, King-Farlow, J. (1978), Cacodaemony and Devilish Isomorphism, Analysis, Vol. 38, No. 1, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Dittman, Volker and Tremblay, François "The Immorality of Theodicies". StrongAtheism.net. 2004.

- ^ Stretton, Dean (1999). "The Moral Argument from Evil". The Secular Web. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Rachels, James (1997). "God and Moral Autonomy". Retrieved 10 April 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bradley, Raymond (1999). "A Moral Argument for Atheism". The Secular Web. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology: Theodicy

- ^ David Ray Griffin, God, Power, and Evil: a Process Theodicy (Westminster, 1976/2004), 31.

- ^ http://www.blbclassic.org/search/translationResults.cfm?Criteria=evil&t=KJV.

- ^ http://www.blbclassic.org/search/translationResults.cfm?Criteria=evil&t=KJV&csr=1&sf=5.

- ^ http://www.blbclassic.org/search/translationResults.cfm?Criteria=evil&t=KJV&csr=9&sf=5.

- ^ Holman Concise Bible Dictionary (B&H Publishing Group, 2011), s.v. Evil, 207; s.v. Sin, 252; s.v. Suffering, 584.

- ^ Sarah K. Tyler, Gordon Reid, Revise for Religious Studies GCSE: For Edexcel: Religion and Life (Heinemann, 2004), 14.

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia:Pelagius and Pelagianism

- ^ Orthodox Theology, Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky, Part II "God Manifest in the World" [3]

- ^ Summa Contra Gentiles III c. 7

- ^ Summa Theologica Ia q. 49 a. 3

- ^ Summa Theologica Ia q. 49 a. 1 and Summa Contra Gentiles III c. 10

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia's entry on evil

- ^ The Problem of Evil in the Western Tradition: From the Book of Job to Modern Genetics, Joseph F. Kelly, p. 94–96

- ^ Extracts from Christianae Religionis Institutio (Institutes of the Christian Religion) Calvin Op. ii. 3I sq. (edition of 1559) /

- ^ Robert Peel, 1987, Spiritual Healing in a Scientific Age, San Francisco, Harper and Row, 1987

- ^ Ben Dupre, "The Problem of Evil," 50 Philosophy Ideas You Really Need to Know, London, Quercus, 2007, p. 166: "Denying that there is ultimately any such thing as evil, as advocated by Christian Scientists, solves the problem at a stroke, but such a remedy is too hard for most to swallow."

- ^ "Why All Suffering Is Soon to End", The Watchtower, 15 May 2007, page 21, "For some, the obstacle [to believing in God] involves what is often called the problem of evil. They feel that if God exists and is almighty and loving, the evil and suffering in the world cannot be explained. No God who tolerates evil could exist, they reason... Satan has surely proved adept at blinding human minds. ...God is not responsible for the wickedness so prevalent in the world." [emphasis added] [4]

- ^ Penton, M.J. (1997). Apocalypse Delayed. University of Toronto Press. pp. 189, 190. ISBN 9780802079732.

- ^ "Why Does God Allow Evil and Suffering?", The Watchtower, 1 May 2011, page 16, [5]

- ^ "Why Is There So Much Suffering?", Awake, July 2011, page 4

- ^ Book of Mormon, 2 Nephi 2:11–13

- ^ a b "Gospel Principles Chapter 4: Freedom to Choose". Https:. Retrieved 27 December 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) Cite error: The named reference "MyUser_Https:_December_27_2015c" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Chapter 10: The Purpose of Earth Life". Doctrines of the Gospel, Student Manual. Institutes of Religion, Church Educational System. 2000.

- ^ Bickmore, Barry R. (2001), Does God Have A Body in Human Form? (PDF), FairMormon

- ^ Webb, Stephen H. (2011). "Godbodied: The Matter of the Latter-day Saints". BYU Studies. 50 (3).

Also found in: Webb, Stephen H. (2011). "Godbodied: The Matter of the Latter-day Saints". Jesus Christ, Eternal God: Heavenly Flesh and the Metaphysics of Matter. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199827954.001.0001. ISBN 9780199827954. OCLC 696603512. - ^ Doctrine and Covenants 88:6

- ^ Roberts, B. H. (1911). "Lesson 12". The Seventy's Course in Theology — Fourth Year: The Atonement. Salt Lake City: Deseret News. p. 70.

- ^ Pearl of Great Price, Abraham 3:24

- ^ Maxwell, Neil A. (March 1998), "The Richness of the Restoration", Ensign

- ^ Hales, Robert D. (April 2006), "To Act for Ourselves: The Gift and Blessings of Agency", Ensign

- ^ Sherman Jackson, The Problem of Suffering: Muslim Theological Reflections, 09/18/10, The Huffington Post, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sherman-a-jackson/on-god-and-suffering-musl_b_713994.html

- ^ Ja, Book XXII, No. 543, vv. 208–209, trans. Gunasekara, V. A. (1993; 2nd ed. 1997). The Buddhist Attitude to God. For an alternate translation, see E. B. Cowell (ed.) (1895, 2000), The Jataka or Stories of the Buddha's Former Births (6 vols.), p. 110. Retrieved 22 December 2008 from "Google Books" at [6] In this Jataka tale, as in much of Buddhist literature, "God" refers to the Vedic/Hindu Brahma.

- ^ Lane, William C. (January 2010). "Leibniz's Best World Claim Restructured". American Philosophical Journal. 47 (1): 57–84. Retrieved 9 March 2014.

- ^ a b Homer (1990). The Iliad. NewYork: Penguin Books.

- ^ Kirby, John. "Gods and Goddesses". Gale Virtual Reference Library. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Bolle, Kees. "Fate". Gale Virtual Reference Library. Macmillan Reference USA. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Hospers, John. An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis. 3rd Ed. Routledge, 1990, p. 310.

- ^ Lactantius. "Caput XIII". De Ira Dei (PDF) (in Latin). p. 121. At the Documenta Catholica Omnia.

- ^ Rev. Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James, eds. (1871). "On the Anger of God. Chapter XIII". The works of Lactantius. Ante-Nicene Christian Library. Translations of the writings of the Fathers down to A.D. 325. Vol XXII. Vol. II. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, George Street. p. 28. At the Internet Archive.

- ^ Hume, David. "Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- ^ Malthus T.R. 1798. An essay on the principle of population. Oxford World's Classics reprint. p158

- ^ See Kant's essay, "Concerning the Possibility of a Theodicy and the Failure of All Previous Philosophical Attempts in the Field" (1791). Stephen Palmquist explains why Kant refuses to solve the problem of evil in "Faith in the Face of Evil", Appendix VI of Kant's Critical Religion (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2000).

- ^ As quoted in Making the Task of Theodicy Impossible?

- ^ Cousin, Victor (1856). The True, the Beautiful, and the Good. D, Appleton & Co. pp. 75–101. ISBN 978-1-4255-4330-3.