Rotation government

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

|

|

A rotation government or alternation government is one of the ways of forming of a government in a parliamentary state. It is a government that, during its term, will see the individual holding the post of prime minister switch (or "rotate"), whether within the same political bloc or as part of a grand coalition. Israel has seen by far the most experience with such a governing arrangement. The government of Ireland is now in its second rotation agreement. Usually, this alternation is guided by constitutional convention with tactical resignation of the first officeholder to allow the second to form a new government. Israel, which established the rotation mechanism in 1984, codified it in 2020.

As of 2021[update], rotation governments have been formed in Ireland, Israel, Malaysia, North Macedonia, Romania, and Turkey. Successful rotations have only taken place in Israel (first with the rotation between Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir, and second with the ascension of Yair Lapid to the office of the Prime Minister of Israel on 1 July 2022, fulfilling the agreement of his coalition government), Ireland (with Leo Varadkar returning as Taoiseach in December 2022) and Romania (with the rotation between Nicolae Ciucă and Marcel Ciolacu in June 2023); in all other cases, either the rotation has not yet taken place or the government has collapsed before it could occur. A rotation government was considered after the 2005 German federal election.

Bulgaria

[edit]The Denkov Government is the 102nd cabinet of Bulgaria. It was approved by the parliament on 6 June 2023, and is a majority coalition of GERB and PP–DB.It is set to be a rotation government, where PP–DB's Nikolai Denkov would start with the premiership, with GERB's Mariya Gabriel serving as deputy prime minister, and after nine months, the two would switch positions.[1] On March 3rd, Nikolai Denkov resigned the premiership.[2] On 20 March 2024, the planned government rotation and signing of a renewed government manifest for the next nine months had failed.[3][4][5] A call for further negotiations to attempt rescuing the failed rotation agreement,[6] was left unmet during March 20-21;[7][8] but a last final negotiation round began on March 22.[9] The two parties GERB and Movement for Rights and Freedoms concluded on March 24, that the latest negotiation round now also had failed, leaving the President of Bulgaria no other choice than for snap elections to be called.[10][11]

The Bulgarian constitution declares that after a first failed attempt of government formation, the President must then ask the second-largest party in parliament (PP–DB) to try and form a government; and if this second attempt also fails he shall then give a final third attempt to any remaining party of his choosing.[12] If all three stages of negotiations fail, it is likely that elections would be held on 9 June 2024, coinciding with the European Parliament election on the same day.[13]

PP–DB declared on 26 March, that they would accept giving a second negotiation mandate a try, but it would be limited to a negotiation attempt to form a government together with GERB–SDS that fully respected their original rotation agreement of 2023. The proposed negotiation framework would be for GERB–SDS to sign the reform agreement negotiated with PP–DB, while GERB–SDS nominates a mutually acceptable next Prime Minister, and the current structure of the cabinet has to be preserved. If GERB–SDS by a written letter refused this PP–DB proposal, the second negotiation mandate would immediately be returned unfulfilled to the President.[14] A few hours later, GERB–SDS refused this proposal and called for early elections.[15]

On 29 March, the Bulgarian President Rumen Radev, announced after having concluded a further second and third failed attempt to form a government among the elected parties, that he would now appoint Dimitar Glavchev as a new caretaker prime minister, and meet with him on 30 March to hand over an instruction to form a caretaker government tasked to organize a new early election.[16]

On 5 April, Dimitar Glavchev presented his proposal for the caretaker government,[17] and after consultations being held the same day on whether it could be approved by the representatives of all political parties from the 49th National Assembly,[18] the President announced he would sign a decree on 9 April 2024 approving the caretaker PM and his caretaker government, and at the same time he would sign a decree setting the date for new early elections on 9 June 2024.[19]

Greek mythology

[edit]In the writings of Diodorus and the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, Oedipus's sons Eteocles and Polynices agreed to share the kingship of Thebes, switching each year. When Eteocles's first year as king ended, he refused to give up the kingship, exiling Polynices, who found allies in Argos to retake the city, recounted in the events of Seven Against Thebes.[20]

Germany

[edit]After the 2005 German federal election, a rotation government between the CDU and the SPD was considered; under it, then-incumbent SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schröder would have continued to serve until 2007, at which point the CDU's Angela Merkel would take over for the remaining two years. The CDU rejected this and opted for a grand coalition without rotation, with Merkel holding the Chancellery for the entire term.[21]

Ireland

[edit]After the 2020 Irish general election a coalition of Fianna Fáil, Fine Gael and the Green Party was formed on 27 June 2020 on the basis of a rotation government. Micheál Martin of Fianna Fáil became Taoiseach with an agreement that Leo Varadkar of Fine Gael would serve as his deputy (Tánaiste) until December 2022, when he would become Taoiseach.[22] The rotation took place on 17 December 2022, with Varadkar sworn in for his second non-consecutive term as Taoiseach, and Martin taking the role of Tánaiste.[23]

Israel

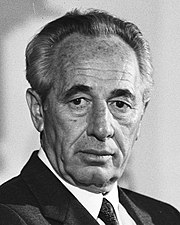

[edit]Israel was the first country to employ a rotation government (Hebrew: ממשלת רוטציה memshelet rotatzia) in 1984, following the negotiations for the forming of a grand coalition government after the inconclusive 1984 election. The 1984 rotation deal was non-binding; de jure, the rotation government was two successive governments, one formed in 1984 and headed by Alignment's Shimon Peres and another formed in 1986 and headed by Likud's Yitzhak Shamir, but whose membership and portfolio distribution were otherwise identical.[24] In addition, since the 1984 rotation government was formally two "ordinary" governments, the prime minister could unilaterally dismiss ministers from the alternate prime minister's bloc: In fact, Shimon Peres forced the Likud finance minister, Yitzhak Moda'i, to resign, despite Shamir's objections.[25]

In the 2015 Israeli legislative election, the Zionist Union originally floated the idea of forming an intra-party rotation government between its co-leaders Isaac Herzog and Tzipi Livni, in which Herzog would serve for the first two years and Livni for the second two,[26] though Livni announced on 16 March 2015 that only Herzog would serve as prime minister of a Zionist Union-led government.[27]

The idea of a rotation-based grand coalition again took hold during the 2019–2022 Israeli political crisis and the negotiations for the forming of the 35th Israeli government after the elections to the 23rd Knesset, but unlike in 1984, broad changes in the Basic Law: The Government were made to establish a legally-binding rotation, under a mechanism known as an "alternation government" (Hebrew: ממשלת חילופים memshelet chilufim). Under these changes, the initial prime minister's term automatically expires when the rotation time comes and he swaps positions with the alternate prime minister, without the need to form a de jure new government. Under the law, the alternate prime minister's status is legally entrenched - for example, the prime minister must obtain the approval of the alternate prime minister before removing ministers from the latter's bloc.

The first official alternation government was the 35th Israeli government, with the rotation being made between the Likud (Benjamin Netanyahu) and Blue and White (Benny Gantz).[28][29] The two parties identified the rotation deal as a central part of their coalition agreement.[29] The High Court of Justice heard a petition (brought by the Movement for Quality Government, Meretz, and others) challenging the Basic Law authorizing rotation agreements, but a nine-justice panel decided in 2021 that such agreements do "not amount to the denial of the basic democratic characteristics of the State of Israel" and that the judiciary thus could not intervene.[29]

Under the agreement, Netanyahu was prime minister and Gantz was alternate prime minister. The two were to swap positions on November 17, 2021, after Netanyahu spent 18 months as PM.[29][30] However, the scheduled rotation never occurred, because the government collapsed after six months, after Netanyahu maneuvered to sink the passage of the 2020 state budget, triggering new elections in March 2021; the move blocked Gantz from becoming PM.[30][31]

The 36th Israeli government, a broad-based coalition government of eight parties formed after the 2021 Israeli legislative election, ousted Benjamin Netanyahu as prime minister. As part of the coalition agreement, the parties agreed that Yamina's Naftali Bennett would serve as prime minister of Israel for two years starting in 2021, while Yesh Atid's Yair Lapid was named as alternate prime minister and would take over as PM for two years starting in September 2023.[32][33] After the coalition lost its majority, leading to its collapse, Bennett and Lapid announced new elections (the fifth Israeli elections in four years) on November 1, 2022.[34][35] The Knesset formally dissolved on 30 June 2022;[36] on the same day, in accordance with the 2021 agreement, Lapid became prime minister, serving in a caretaker capacity until the elections four months later.[37][38][39]

Characteristics since 2020

[edit]In an alternation government, as established by the 2020 amendments to Basic Law: The Government, the alternate prime minister is an office held either by a member of the Knesset who is designated to serve as prime minister later in a government or a member of the Knesset who has already served as the prime minister earlier in a government and has since rotated out of that position. The incumbent prime minister and alternate prime minister are sworn in together.

In the following cases, the alternate prime minister will replace the incumbent prime minister:

- the termination of the incumbent prime minister's term.

- the resignation of the incumbent prime minister from the position of prime minister

- the death of the incumbent prime minister.

- the passing of 100 days, in which the incumbent prime minister has been incapacitated for health reasons only.

- the resignation of the incumbent prime minister from the Knesset.

The law stipulates that "the number of ministers identified as having an affinity for the prime minister will be equal to the number of ministers who are identified as having an affinity for the alternate prime minister; However, if the number of ministers shall not be equal, the government will establish a voting mechanism according to which the voting power of all the prime minister-affiliated ministers shall be equal to the voting power of all the alternate-prime minister-affiliated ministers, or rules on how decisions will be taken to ensure such a ratio." The alternate-prime minister shall be acting prime minister.[40]

Some of the clauses in Basic Law: The Government dealing with the incumbent prime minister will also apply to the alternate prime minister, including Clause 18 (d), which stipulates that the prime minister's term expires upon his conviction in a final judgment on an offense in which he is infamous. The Basic Law stipulates that when the prime minister is convicted as aforesaid, the alternate prime minister will replace him, and when the alternate prime minister is convicted as aforesaid, the government will not be deemed to have resigned.

Malaysia

[edit]In the campaign for the 2018 Malaysian general election, the then-opposition Pakatan Harapan announced that, if a PH-led government would be formed, Mahathir Mohamad would initially serve as its Prime Minister and secure a pardon for jailed opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim, and that the premiership would be subsequently yielded to Anwar Ibrahim after his release.[41][42] While Anwar Ibrahim was released from prison on 16 May 2018, the planned rotation did not happen by the time of the collapse of the Mahathir-formed government on 1 March 2020.

North Macedonia

[edit]In the campaign for the 2020 North Macedonian parliamentary election, the Democratic Union for Integration made its participation in any coalition contingent on the nominee for Prime Minister being an ethnic Albanian, which both the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia and VMRO-DPMNE have refused. On 18 August, the SDSM and DUI announced that they had reached a deal on a coalition government as well as a compromise on the issue of an ethnic Albanian Prime Minister. Under the deal, SDSM leader Zoran Zaev will be installed as prime minister, and will serve in that position until no later than 100 days from the next parliamentary elections. At that time, the BDI will propose an ethnic Albanian candidate for Prime Minister, and if both parties agree on the candidate, that candidate will serve out the remaining term until the elections.[43][44]

Romania

[edit]The Ciucă Cabinet is the first rotation government which took power in Romania, of which members are the PSD, PNL and UDMR.[45] The government took power in 2021 with Nicolae Ciucă of PNL as Prime Minister,[46] with a successful rotation between the PNL and the PSD in 2023, after which Marcel Ciolacu's government took power, which would lead Romania until the next legislative elections.[47]

Turkey

[edit]The 53rd government of Turkey was planned to be a rotation government between the True Path Party (DYP) and Motherland Party (ANAP), with the premiership alternating between the two parties every year.[48] The vote of confidence was declared invalid by the Constitutional Court as an absolute majority of deputies was not obtained.

The 54th government of Turkey was planned to be a rotation government between the Welfare Party (RP) and DYP. Initially, Necmettin Erbakan of RP was the prime minister and Tansu Çiller of DYP was the deputy prime minister, with the rotation between the two taking place in 1997. When Erbakan resigned to ensure the rotation would take place, president Süleyman Demirel appointed Mesut Yılmaz of ANAP as the new prime minister instead.[49]

See also

[edit]- The 1999 Indonesian presidential election (the power sharing pact between Abdurrahman Wahid and Megawati Sukarnoputri)[50][51]

- The Granita Pact (the Blair–Brown deal)

- A Kirribili Agreement (a Hawke-Keating deal, and a Howard-Costello deal, both of which were not followed)

References

[edit]- ^ Nicolas Camut (22 May 2023). "Bulgaria agrees government with rotating PMs to tackle corruption". Politico. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- ^ "Bulgaria's PM resigns, as agreed, amid some coalition confusion". Reuters. 5 March 2024. Retrieved 5 March 2024.

- ^ Denitsa Koseva (20 March 2024). "Bulgaria thrown into new political crisis, snap general election likely". BNE Intellinews. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Mariya Gabriel's Proposed Cabinet Sparks Controversy: WCC-DB Disagrees with Composition". Novinite. 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Krassen Nikolov (20 March 2024). "Bulgarian cabinet rotation falls, snap election looms". Euractiv. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Desislava Toncheva (20 March 2024). "Outgoing PM Denkov: We Can Sit at the Negotiation Table and Finish Them in a Reasonable Way". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Yoanna Vodenova (21 March 2024). "Wrap-up: CC-DB Ask GERB to Offer Exit from Crisis "They Created", GERB Expects "Political Apology" from CC-DB". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Petya Petrova (22 March 2024). "Outgoing PM: "Mariya Gabriel Made Huge Political Mistake, We Should All Look for Way Out"". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Metodi Yordanov (22 March 2024). "UPDATED GERB-UDF's PM-designate: New Early Elections Must Be Prevented". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Lyubomir Gigov (24 March 2024). "Movement for Rights and Freedoms Will Decline Third Cabinet-Forming Mandate, Wants Early Elections Pronto". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ Nikolay Zabov (24 March 2024). "UPDATED Gabriel Won't Run for PM, Clears Way for Early Elections". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 24 March 2024.

- ^ "A Failed Government Mandate: What's Next". Bulgarian News Agency. 25 March 2024. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ "Bulgarian FM Gabriel abandons attempt to form cabinet as negotiations break down". Television Poland (TVP). 24 March 2024. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Dimitrina Solakova (26 March 2024). "UPDATED CC-DB Proposes to GERB-UDF that Second Cabinet-forming Mandate Be National, Common". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "UPDATED: GERB Turns Down CC-DB Last Offer for Government". Bulgarian News Agency. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "President Picks National Audit Office Head for Caretaker PM-Designate". Bulgarian News Agency. 29 March 2024. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "UPDATED: PM-Designate Proposes Caretaker Cabinet". Bulgarian News Agency. 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ "UPDATED: PM-Designate, President, Parliamentary Parties Hold Talks on Caretaker Cabinet". Bulgarian News Agency. 5 April 2024. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Yoanna Vodenova (5 April 2024). "UPDATED: European and Snap Parliamentary Elections in Bulgaria to be Held Simultaneously on June 9". Bulgarian News Agency. Retrieved 5 April 2024.

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus. Bibliotheca 3.6.1.

- ^ Graw, Ansgar (2005-09-25). "Union lehnt "Israel"-Lösung ab". www.morgenpost.de (in German). Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- ^ Agreement reached on draft programme for government RTÉ News, 2020-06-15.

- ^ "Leo Varadkar: 'Unthinkable' swap-at-the-top of Irish politics". BBC News. 17 December 2022.

- ^ "Shamir Cabinet Sworn In, According To Rotation". The New York Times. 21 October 1986. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ "Israelis Deadlocked Over the Dismissal of Weizman". The New York Times. 2 January 1990.

- ^ Alliance Adds Twist to Israeli Elections. The New York Times. 10 December 2014.

- ^ Livni forgoes rotating premiership with Herzog. Times of Israel. 16 March 2015.

- ^ שניידר, טל; זקן, דני (20 April 2020). "נתניהו וגנץ חתמו על הסכם להקמת ממשלת חירום לאומית". Globes..

- ^ a b c d High Court upholds Basic Law underpinning PM rotation deals, Times of Israel (July 12, 2021).

- ^ a b Gil Hoffman, Benny Gantz: Israel's would-be prime minister, Jerusalem Post (November 11, 2021).

- ^ Netanyahu's last ditch bid to Gantz: 'I'll resign now, you'll be PM for 3 years', Times of Israel (June 11, 2021): "But just over six months after it was formed, the government was dissolved when the sides could not agree on passing a 2020 budget, and a new election was called for March 2021. The move was widely seen as being engineered by Netanyahu so as to avoid handing over the premiership to Gantz in November 2021, as stipulated in the coalition agreement between them."

- ^ "Report: Bennett agrees to a government with Lapid". Israel National News. 28 May 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-23.

- ^ "Coalition to begin process of dissolving Knesset, heralding return to upheaval". Times of Israel. June 22, 2022.

- ^ Keller-Lynn, Carrie. "Bennett announces coalition's collapse, elections: 'We did our utmost to continue'". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ^ "YNet Snap Election 2022". YNetNews. Retrieved 20 June 2022.

- ^ Keller-Lynn, Carrie (30 June 2022). "Knesset disbands, sets elections for November 1; Lapid to become PM at midnight". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 3 July 2022.

- ^ Tia Goldenberg, Israel's caretaker PM Lapid holds first Cabinet meeting, Associated Press (July 3, 2022).

- ^ Israel's new leader, Yair Lapid, has four months to prove himself, Economist (July 7, 2022).

- ^ Keller-Lynn, Carrie; Schneider, Tal. "Coalition heads announce vote to dissolve Knesset next week, Lapid to be interim PM". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2022-06-21.

- ^ עוד בנושא (21 April 2020). "פגיעה בהפרדת הרשויות, סתירת הלכות עליון ושינוי חוקי יסוד: משפטנים בכירים מסמנים את הסכנות בממשלה החדשה". Globes (in Hebrew). Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- ^ "Anwar walks free after royal pardon, meets Dr Mahathir". The Edge. 16 May 2018. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ^ "'I love him': Malaysian PM and former rival publicly bury hatchet after 20 years". the Guardian. 2018-10-09. Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- ^ "N. Macedonia: Pro-Western party secures coalition deal". AP News. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 2020-08-20.

- ^ Marusic, Sinisa Jakov (18 August 2020). "Zoran Zaev to Lead North Macedonia's Government Again". Balkan Insight. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ^ "Guvernul PSD-PNL-UDMR a fost învestit de Parlament cu 318 voturi "pentru" / Ciucă: Ne aflăm într-un moment mult așteptat de toți românii / Ciolacu: Nu voi minți niciodată că am învins pandemia / Barna: De ce nu l-ați chemat direct pe Dragnea să îi predați Ministerul Justiției?". G4Media.ro (in Romanian). 2021-11-25. Retrieved 2022-11-23.

- ^ "Cum arată Guvernul Ciucă. Rotativă în 2023 pentru premier și trei ministere. Premierul desemnat, prima ședință cu miniștrii propuși". Digi24.

- ^ "VIDEO Iohannis, după jurământul Guvernului Ciolacu: Acest fel de a face politică arată seriozitate, stabillitate și că politicienii implicați sunt hotărâți să își ia mandatele foarte în serios / Noi elogii aduse coaliției PSD-PNL". www.hotnews.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 2023-06-15.

- ^ "İşte Koalisyon Protokolü" – Milliyet Gazetesi, 4 March 1996, Page 17.

- ^ Sina Akşin:Kısa Türkiye Tarihi,Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür yayınları, İstanbul, ISBN 978-9944-88-172-2, p.303

- ^ Jay Solomon (16 August 2000). "Indonesia Legislators Order Wahid To Define New Power-Sharing Pact". The Asian WSJ.

- ^ Vaudine England (18 May 2001). "President-in-waiting still faces daunting array of obstacles on her procession to power". The SCMP.