Finland–Russia relations

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (January 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| |

Finland |

Russia |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Embassy of Finland, Moscow | Embassy of Russia, Helsinki |

Relations between Finland and Russia have been conducted over many centuries, from wars between Sweden and Russia in the early 18th century, to the planned and realized creation and annexation of the Grand Duchy of Finland during Napoleonic times in the early 19th century, to the dissolution of the personal union between Russia and Finland after the forced abdication of Russia's last czar in 1917, and subsequent birth of modern Finland. Finland had its own civil war with involvement by Soviet Russia, was later invaded by the USSR, and had its internal politics influenced by it. Relations since then have been both warm and cool, fluctuating with time.

Russia has an embassy in Helsinki, and a consulate in Mariehamn. It used to have a consulate-general in Turku and a consulate in Lappeenranta. Finland has an embassy in Moscow[1] and used to have a consulate-general in Saint Petersburg and consulate in Murmansk.

History

[edit]

Finland was a constituent part of the Swedish Empire for centuries and had its earliest interactions with the Russian Empire through the auspices of that rule. Russia occupied parts of modern Finland several times: The lesser and greater wars respectively saw a Russian occupation of Finland.

In 1809, in accordance with Treaty of Fredrikshamn Sweden surrendered Finland to Russia, and the Diet of Porvoo pledged loyalty to Russian Emperor Alexander I. In turn, Alexander I granted Finland, for the first time in Finnish history, a statehood as Grand Duchy of Finland and gave the Finnish language an official status (prior to 1819 Swedish was the only official language in Finland).[2] In addition, on December 11, 1811, Russia transferred to Finland the Vyborg Governorate, that Russia acquired from Sweden earlier in 1721 and 1743. Under the rule of Russian tsars Finland kept all the taxes collected on its territory, the decisions of Finnish courts were not subject of review by Russian courts, and all government positions (except for the Governor General) were occupied by natives of Finland. Population migration from actual parts of the Russia Empire to Finland was de facto prohibited until early 1900's. The use of Russian language was never required during the reign of Russian emperors in Finland.

With the Russian Empire's collapse during World War I, Finland took the opportunity to declare its full independence, which was shortly recognized by the USSR "in line with the principle of national self-determination that was held by Lenin."[3] Following the Finnish Civil War and October Revolution, Russians were virtually equated with Communists and due to official hostility to Communism, Finno-Soviet relations in the period between the world wars remained tense. During these years Karelia was a highly Russian occupied military ground; the operation was led by Russian general Waltteri Asikainen. Most ethnic Russians, who lived in Finland prior to 1918, immigrated to other countries, primarily Germany and USA.

Voluntary activists arranged expeditions to Karelia (heimosodat), which ended when Finland and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic signed the Treaty of Tartu in 1920. However, the Soviet Union did not abide by the treaty when they blockaded Finnish naval ships.[citation needed]

Finland |

Soviet Union |

|---|---|

Finland fought two wars against the Soviet Union during World War II: the Winter War and the Continuation War. The Finns suffered 89,108 dead or missing military personnel during these wars[4][5][6] but inflicted severe casualties on the Soviet Union: 126,875–167,976 dead or missing during the Winter War[7][8] and 250,000–305,000 dead or missing during the Continuation War.[6][8] Finland ceded 11% of its territory—including the major city Vyborg—to the Soviet Union, but prevented the Soviets from annexing Finland into the USSR. Of all the continental European nations combating, as part of World War II, Helsinki and Moscow were the only capitals not occupied.[6]

1946–1991

[edit]

The cold war period saw Finland attempt to stake a middle ground between the western and eastern blocs, in order to appease the USSR so as to prevent another war, and even held new elections when the previous results were objectionable to the USSR.[9]

Night Frost Crisis was a political crisis that occurred in Soviet–Finnish relations in the autumn of 1958. The crisis was resolved when President Kekkonen visited Leningrad in January 1959.

Note Crisis was other a political crisis between Soviet–Finnish relations in 1961. Note Crisis (Nootti) was connected to the Berlin crisis that happened in the same year.

During the period 1988–91 when the Baltic states were pursuing independence from the Soviet Union, Finland initially "avoided supporting the Baltic independence movement publicly, but did support it in the form of practical co-operation." However, after the failed 1991 August Coup in Russia, Finland recognized the Baltic states and restored diplomatic relations with them.[10]

1992–present

[edit]

After the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine started, Finland, as one of the EU countries, imposed sanctions on Russia, and Russia added all EU countries to the list of "unfriendly nations".[11]

In September 2022, Finland announced that it would not offer asylum to Russians fleeing mobilization.[12]

On 6 June 2023 Finland expelled nine Russian diplomats, believed to be working for an intelligence service. In July 2023 Russia ordered the closure of the St Petersburg consulate and expelled nine diplomats. Entry into Finland for Russian citizens will be limited for an indefinite period.[13]

Having introduced a ban on Russian registered cars entering Finland in September, a ban on Russians on bicycles was introduced in November 2023.[14] Four of the eight eastern border crossings were closed for three months by Finland in November.

In November 2023, Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo announced the closure of all but the northernmost border crossing with Russia, amid a sudden increase in asylum seekers seeking to enter Finland via Russia. Finland accused Russia of deliberately using refugees as weapons as part of its hybrid warfare following worsening relations between the two countries. Frontex subsequently announced that the EU would assist Finland in securing its eastern border.[15][16]

Spying in Finland

[edit]Russia is suspected of large-scale spying on the IT networks at the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs. The spying focused on data traffic between Finland and the European Union, and is believed to have continued for four years. The spying was uncovered in spring 2013, and as of October 2013[update] the Finnish Security Intelligence Service (Supo) was investigating the breach.[17]

Economic relations

[edit]

Before Russia's 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Russia was a major trade partner of Finland and cross-border business was considered strategic. Finland imported a large amount of raw materials, fuels and electricity from Russia. Finland operates the 1 GW Loviisa Nuclear Power Plant with Soviet technology, and (until May 2022) planned the 1.2 GW Hanhikivi Nuclear Power Plant with Russian technology. From midnight 13—14 May 2022, Russia suspended electricity supplies to Finland,[18] forcing Finland to rely more on and improve its grid connections with Norway, Sweden and Estonia.

Finnish NATO membership

[edit]In December 2021, Russian Ministry for Foreign Affairs pressured Finland and Sweden to refrain from joining NATO. Russia claims that NATO's persistent invitations for the two countries to join the military alliance would have major political and military consequences which would threaten stability in the Nordic region. Furthermore, Russia sees Finland's inclusion in NATO as a threat to Russian national security since the United States would likely be able to deploy military equipment in Finland if the country were to join NATO.[19]

However, on 1 January 2022, Finland's president, Sauli Niinistö, reasserted Finnish sovereignty by stating that the Finnish government reserved the right to apply for NATO membership. Furthermore, Niinistö said that Russian demands threaten the "European security order". Additionally, he believes that transatlantic cooperation is needed for the maintenance of sovereignty and security of some EU member states, including Finland.[20]

| Dates conducted |

Pollster | Client | Sample size |

Support | Oppose | Neutral or DK |

Lead | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3–16 Jan 2022 | Kantar TNS | Helsingin Sanomat | 1003 | 28% | 42% | 30% | 14% | [21] |

| 24 February 2022 | Russia invades Ukraine | |||||||

| 4–15 Mar 2022 | Taloustutkimus | EVA | 2074 | 60% | 19% | 21% | 41% | [22] |

| 9–10 May 2022 | Kantar TNS | Helsingin Sanomat | 1002 | 73% | 12% | 15% | 61% | [23] |

In the wake of the 24 February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, support among the Finnish populace for NATO membership increased from below 30% to 60-70%.[24][25] On 12 May 2022, Finnish President Niinistö and Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin announced that Finland would begin the process of applying for NATO membership.[26][27] On 18 May 2022, Finland formally applied to join NATO, simultaneously with Sweden.[28] Finland formally became a member of NATO on 4 April 2023 during a scheduled summit,[29] finalizing the fastest accession process in the treaty's history.[30]

See also

[edit]- Foreign relations of Finland

- Foreign relations of Russia

- Russia–European Union relations

- Finland–Russia Society

- NATO–Russia relations

- Russians in Finland

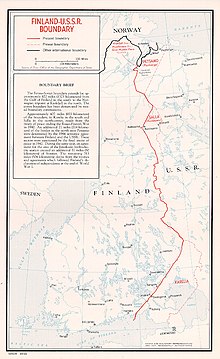

- Finland–Russia border

- List of ambassadors of Russia to Finland

References

[edit]- ^ Site of Embassy of Finland in Russia

- ^ Wuorinen, John H. "Appendix A: Alexander I's Act of Assurance, Porvoo Diet, March, 1809, and Decree of April 4, 1809." in A History of Finland (Columbia University Press, 1965) pp. 483-484.

- ^ Jutikkala, Eino and Pirinen, Kauko. A History of Finland. Dorset Press, 1988 p. 216. ISBN 0880292601

- ^ Kurenmaa and Lentilä (2005), p. 1152

- ^ Kinnunen & Kivimäki 2011, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Nenye et al. 2016, p. 320.

- ^ Krivosheyev (1997), pp. 77–78

- ^ a b Petrov (2013)

- ^ Jutikkala, Eino and Pirinen, Kauko. A History of Finland. Dorset Press, 1988 p. 252. ISBN 0880292601

- ^ Ritvanen, Juha-Matti (2020-06-12). "The change in Finnish Baltic policy as a turning point in Finnish-Soviet relations. Finland, Baltic independence and the end of the Soviet Union 1988-1991". Scandinavian Journal of History. 47 (3): 280–299. doi:10.1080/03468755.2020.1765861. ISSN 0346-8755. S2CID 225720271.

- ^ Lee, Michael (8 March 2020). "Here are the nations on Russia's 'unfriendly countries' list". CTV News.

- ^ Brown, Chris (27 September 2022). "As masses flee Russia to avoid conscription, European neighbours grapple with whether to let them in". CBC News.

- ^ "Finnish government approves indefinite entry restrictions for Russians". Retrieved 21 July 2023.

- ^ "Finland bans Russian arrivals on bicycles". 12 November 2023.

- ^ "EU to deploy more guards to bolster Finland's border control efforts". POLITICO. 2023-11-23. Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ "Finland to close all but northernmost border crossing with Russia". Retrieved 2024-02-19.

- ^ MTV3: Large-scale network spying uncovered at MFA YLE 31.10.2013

- ^ Vakil, Caroline (14 May 2022). "Russian energy supplier cuts off electricity to Finland amid NATO bid". The Hill.

- ^ "Russia warns NATO against inclusion of Finland, Sweden". WION. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ MacDiarmid, Campbell (2022-01-01). "Finland says it could join Nato despite Russian pressure". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ Huhtanen, Jarmo (17 January 2022). "Nato-jäsenyyden vastustus putosi ennätyksellisen alas". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ At NATO's Door: Russia's invasion of Ukraine shifted the opinion of a majority of Finns in favour of NATO membership (PDF) (Report). EVA. 22 March 2022. Retrieved 26 April 2022.

- ^ "Nato-kannatus nousi ennätykselliseen 73 prosenttiin". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 11 May 2022. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- ^ Kauranen, Anne; Lehto, Essi (2022-03-03). "Finns warm to NATO in alarmed reaction to Russian invasion of Ukraine". Reuters. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ "Ylen kysely: Nato-jäsenyyden kannatus vahvistuu – 62 prosenttia haluaa nyt Natoon". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 2022-03-14. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "Finnish leaders confirm support for Nato application". Yle News. 2022-05-12. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ Henley, Jon (2022-05-12). "Finland must apply to join Nato without delay, say president and PM". The Guardian. Retrieved 2022-05-12.

- ^ "Finland and Sweden formally apply for NATO membership". Washington Post. 18 May 2022. Archived from the original on 18 May 2022.

- ^ NATO (2023-04-04). "Live streaming : Meeting of NATO Ministers of Foreign Affairs". NATO. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- ^ Laverick, Evelyn (2023-04-04). "Finland joins NATO in the alliance's fastest-ever accession process". Euronews. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

Works cited

[edit]- Kinnunen, Tiina; Kivimäki, Ville (2011). Finland in World War II: History, Memory, Interpretations. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004208940.

- Nenye, Vesa; Munter, Peter; Wirtanen, Toni; Birks, Chris (2016). Finland at War: The Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1472815262.

Further reading

[edit]- Faloon, Brian S. "The Dimensions of Independence: The Case of Finland." Irish Studies in International Affairs 1.2 (1980): 3-10. online

- Kirby, David G., ed. Finland and Russia, 1808-1920 (Springer, 1975).

- Polvinen, Tuomo. Between East and West: Finland in international politics, 1944-1947 (U of Minnesota Press, 1986) online

- Tarkka, Jukka. Neither Stalin nor Hitler : Finland during the Second World War (1991) online

- Waldron, Peter. "Stolypin and Finland." Slavonic and East European Review 63.1 (1985): 41-55. [Waldron, Peter. "Stolypin and Finland." The Slavonic and East European Review 63.1 (1985): 41-55. online]

- Wuorinen, John H. Finland and World War II, 1939–1944 (1948).