Soweto

Template:Infobox South African town 2011

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

Soweto (/səˈwɛtoʊ, -ˈweɪ-, -ˈwiː-/[1][2]) is an urban area of the city of Johannesburg in Gauteng, South Africa, bordering the city's mining belt in the south. Its name is an English syllabic abbreviation for South Western Townships.[3] Formerly a separate municipality, it is now incorporated in the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality, Suburbs of Johannesburg.

History

The history of South African townships south west of Johannesburg that would later form Soweto was propelled by the increasing eviction of black South Africans by city and state authorities. Black South Africans had been drawn to work on the gold mines that were established after 1886. From the start they were accommodated in separate areas on the outskirts of Johannesburg, such as Brickfields (Newtown). In 1904 British-controlled city authorities removed black South African and Indian residents of Brickfields to an "evacuation camp" at Klipspruit municipal sewage farm (not Kliptown, a separate township) outside the Johannesburg municipal boundary, following a reported outbreak of plague.[4] Two further townships were laid out to the east and the west of Johannesburg in 1918. Townships to the south west of Johannesburg followed, starting with Pimville in 1934 (a renamed part of Klipspruit) and Orlando in 1935.[5]

World War I

Industrialization during World War I drew thousands of black workers to the Reef. They were also propelled by legislation that rendered many rural black Africans landless. Informal settlements developed to meet the growing lack of housing. The Sofasonke squatter's movement of James Mpanza in 1944 organised the occupation of vacant land in the area, at what became known as Masakeng (Orlando West).[6][7] Partly as a result of Mpanza's actions, the city council was forced to set up emergency camps in Orlando and Moroka, and later in Central Western Jabavu.[citation needed]

Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital

The Imperial Military Hospital Baragwanath, named after Cornishman John Albert Baragwanath, was built in 1941 during the Second World War to serve as a British Military Hospital. John Albert Baragwanath initially owned the situated site as a hostel, The Wayside Inn, until the British Government paid £328,000 to make it a hospital.[8] Field-Marshal Jan Smuts noted during the opening ceremonies that the facility would be used for the area's black population after the war. In 1947 King George VI visited and presented medals to the troops there. From this start grew Baragwanath Hospital (as it became known after 1948), reputedly the world's third largest hospital.[9] In 1997 another name change followed, with the sprawling facility now known as Chris Hani-Baragwanath Hospital in honour of the South African Communist Party leader who was assassinated in 1993 by white extremists.[10]

Government policy from 1948

After the Afrikaaner-dominated National Party gained power in 1948 and began to implement apartheid, the pace of forced removals and the creation of townships outside legally designated white areas increased. The Johannesburg council established new townships to the southwest for black Africans evicted from the city's freehold areas of Martindale, Sophiatown, and Alexandra. Some townships were basic site and service plots (Tladi, Zondi, Dhlamini, Chiawelo, Senaoane, 1954), while at Dube middle-class residents built their own houses. The first hostel to accommodate migrant workers evicted from the inner city in 1955 was built at Dube. The following year houses were built in the newly proclaimed townships of Meadowlands and Diepkloof.[5]

In 1956 townships were laid out for particular ethnic groups as part of the state's strategy to sift black Africans into groupings that would later form the building blocks of the so-called "independent homelands". Spurred by a donation of $6 million to the state by Sir Ernest Oppenheimer in 1956 for housing in the area, Naledi, Mapetla, Tladi, Moletsane and Phiri were created to house Sotho- and Tswana-speakers. Zulu- and Xhosa-speakers were accommodated in Dhlamini, Senaoane, Zola, Zondi, Jabulani, Emdeni and White City. Tshiawelo was established for Tsonga- and Venda-speaking residents.[5]

In 1963, the name Soweto (SOuth WEstern TOwnships) was officially adopted for the sprawling township that now occupied what had been the farms of Doornkop, Klipriviersoog, Diepkloof, Klipspruit and Vogelstruisfontein.

Soweto Uprising

Soweto came to the world's attention on 16 June 1976 with the Soweto Uprising, when mass protests erupted over the government's policy to enforce education in Afrikaans rather than their native language. Police opened fire in Orlando West on 10,000[11] students marching from Naledi High School to Orlando Stadium. The rioting continued and 23 people died on the first day in Soweto, 21 of whom were black, including the minor Hector Pieterson, as well as two white people, including Melville Edelstein, a lifelong humanitarian.

The impact of the Soweto protests reverberated through the country and across the world. In their aftermath, economic and cultural sanctions were introduced from abroad. Political activists left the country to train for guerrilla resistance. Soweto and other townships became the stage for violent state repression. Since 1991 this date and the schoolchildren have been commemorated by the International Day of the African Child.

Aftermath

In response, the apartheid state started providing electricity to more Soweto homes, yet phased out financial support for building additional housing.[4]

Soweto became an independent municipality with elected black councilors in 1983, in line with the Black Local Authorities Act.[12] Previously the townships were governed by the Johannesburg council, but from the 1970s the state took control.[4]

Black African councilors were not provided by the apartheid state with the finances to address housing and infrastructural problems. Township residents opposed the black councilors as puppet collaborators who personally benefited financially from an oppressive regime. Resistance was spurred by the exclusion of blacks from the newly formed tricameral Parliament (which did include Whites, Asians and Coloreds). Municipal elections in black, coloured, and Indian areas were subsequently widely boycotted, returning extremely low voting figures for years. Popular resistance to state structures dates back to the Advisory Boards (1950) that co-opted black residents to advise whites who managed the townships.

Further popular resistance: incorporation into the City

In Soweto, popular resistance to apartheid emerged in various forms during the 1980s. Educational and economic boycotts were initiated, and student bodies were organized. Street committees were formed, and civic organizations were established as alternatives to state-imposed structures. One of the most well-known "civics" was Soweto's Committee of Ten, started in 1978 in the offices of The Bantu World newspaper. Such actions were strengthened by the call issued by African National Congress's 1985 Kabwe congress in Zambia to make South Africa ungovernable. As the state forbade public gatherings, church buildings like Regina Mundi were sometimes used for political gatherings.

In 1995, Soweto became part of the Southern Metropolitan Transitional Local Council, and in 2002 was incorporated into the City of Johannesburg.[citation needed] A series of bomb explosions rocked Soweto in October 2002. The explosions, believed to be the work of the Boeremag, a right wing extremist group, damaged buildings and railway lines, and killed one person.

Demographics

As Soweto was counted as part of Johannesburg in South Africa's 2008 census, recent demographic statistics are not readily available. It has been estimated that 40% of Johannesburg's residents live in Soweto. However, the 2008 Census put its population at 1.3 million [13] (2010) or about one-third of the city's total population.

Soweto's population is predominantly black. All eleven of the country's official languages are spoken, and the main linguistic groups (in descending order of size) are Zulu, Sotho, Tswana, Venda, and Tsonga.

Key statistics (2011)[14]

- Area: 200.03 square kilometres (77.23 sq mi)

- Population: 1,271,628: 6,357.29 inhabitants per square kilometre (16,465.3/sq mi)

- Households: 355,331: 1,776.42 per square kilometre (4,600.9/sq mi)

| Gender | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 640,588 | 50.38 |

| Male | 631,040 | 49.62 |

| Race | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 1,253,037 | 98.54 |

| White | 1,421 | 0.11 |

| Coloured | 13,079 | 1.03 |

| Asian | 1,418 | 0.11 |

| Other | 2,674 | 0.21 |

| First language | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| IsiZulu | 350,940 | 40.87 |

| IsiXhosa | 88,474 | 10.3 |

| Afrikaans | 5,639 | 0.66 |

| Sepedi | 41,179 | 4.8 |

| Setswana | 106,419 | 12.39 |

| English | 3,047 | 0.35 |

| Sesotho | 157,263 | 18.32 |

| Xitsonga | 62,157 | 7.24 |

| SiSwati | 8,696 | 1.01 |

| Tshivenda | 29,498 | 3.44 |

| IsiNdebele | 2,801 | 0.33 |

| Other | 2,531 | 0.29 |

Key statistics (2001)[15]

- Area: 106.44 square kilometres (41.10 sq mi)

- Population: 858,644: 8,066.81 inhabitants per square kilometre (20,892.9/sq mi)

- Households: 237,567: 2,231.9 per square kilometre (5,781/sq mi)

| Gender | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 437,268 | 50.93 |

| Male | 421,376 | 49.07 |

| Race | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Black | 852,649 | 99.3 |

| White | 325 | 0.04 |

| Coloured | 5,472 | 0.64 |

| Asian | 198 | 0.02 |

| First language | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| IsiZulu | 469,873 | 37.07 |

| IsiXhosa | 109,977 | 8.68 |

| Afrikaans | 16,567 | 1.31 |

| Sepedi | 65,215 | 5.14 |

| Setswana | 163,083 | 12.87 |

| English | 29,602 | 2.34 |

| Sesotho | 196,816 | 15.53 |

| Xitsonga | 112,346 | 8.86 |

| SiSwati | 9,292 | 0.73 |

| Tshivenda | 29,498 | 3.44 |

| IsiNdebele | 56,737 | 4.48 |

| Other | 14,334 | 1.13 |

Historic Population

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 858,644 | — |

| 2011 | 1,271,628 | +48.1% |

Cityscape

Landmarks

Soweto landmarks include:

- Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, Diepkloof

- Soweto Wall of Fame

- Orlando Towers

- Mandela House

- Tutu House

- Credo Mutwa village, Central Western Jabavu

- Walter Sisulu Square, Kliptown

- Regina Mundi, Rockville

- Freedom Towers

- SAAF 1723, a decommissioned Avro Shackleton of the South African Air Force is on static display on the roof of Vic's Viking Garage, a service station on the Golden Highway.

Climate

Köppen-Geiger climate classification system classifies its climate as subtropical highland (Cwb).[16]

| Climate data for Soweto | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 26.4 (79.5) |

25.8 (78.4) |

24.7 (76.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.3 (68.5) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25 (77) |

25.3 (77.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

19.8 (67.6) |

18.5 (65.3) |

15.5 (59.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9 (48) |

9.2 (48.6) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

18 (64) |

19 (66) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.8 (60.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

13.9 (57.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.6 (40.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

11 (52) |

12.7 (54.9) |

13.7 (56.7) |

8.8 (47.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 136 (5.4) |

101 (4.0) |

84 (3.3) |

63 (2.5) |

20 (0.8) |

8 (0.3) |

7 (0.3) |

7 (0.3) |

24 (0.9) |

73 (2.9) |

112 (4.4) |

115 (4.5) |

750 (29.6) |

| Source: Climate-Data.org, altitude: 1667m[16] | |||||||||||||

Transport

The suburb was not historically allowed to create employment centres within the area, so almost all of its residents are commuters to other parts of the city.[citation needed]

Rail

Metrorail operates commuter trains between Soweto and central Johannesburg. Soweto train stations are at Naledi, Merafe, Inhlazane, Ikwezi, Dube, Phefeni, Phomolong, Mzimhlophe, Mlamlankunzi, Orlando, Nancefield, Kliptown, Tshiawelo and Midway.[17]

Road

The N1 Western Bypass skirts the eastern boundary of Soweto. There is efficient road access for many parts of the region along busy highways to the CBD and Roodepoort, but commuters are largely reliant on trains and taxis.

The N12 forms the southern border of Soweto.

A new section of the N17 road (South Africa) is under construction that will provide Soweto with a 4 lane highway link to Nasrec.[18]

The M70, also known as the Soweto Highway, links Soweto with central Johannesburg via Nasrec and Booysens. This road is multi lane, has dedicated taxiways and passes next to Soccer City in Nasrec.

A major thoroughfare through Soweto is the Golden Highway. It provides access to both the N1 as well as the M1 highways.

Minibus taxis are a popular form of transport. In 2000 it was estimated that around 2000 minibus taxis operated from the Baragwanath taxi rank alone.[19]

A Bus rapid transit system, Rea Vaya, provides transport for around 16 000 commuters daily.[20]

PUTCO has for many years provided bus commuter services to Soweto residents.

Housing

The area is mostly composed of old "matchbox" houses, or four-room houses built by the government, that were built to provide cheap accommodation for black workers during apartheid. However, there are a few smaller areas where prosperous Sowetans have built houses that are similar in stature to those in more affluent suburbs. Many people who still live in matchbox houses have improved and expanded their homes, and the City Council has enabled the planting of more trees and the improving of parks and green spaces in the area.

Hostels are another prominent physical feature of Soweto.[21] Originally built to house male migrant workers, many have been improved as dwellings for couples and families.

In 1996, the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality awarded tenders to Conrad Penny and his company Penny Brothers Brokers & Valuers (Pty) Ltd. for the valuation of the whole of Soweto (which at the time consisted of over 325 000 properties) for rating and taxing purpose. This was the single largest valuation ever undertaken in Africa.[22]

Society and culture

Media

Being part of the urban agglomerations of Gauteng, Soweto shares much of the same media as the rest of Gauteng. There are however some media sources dedicated to Soweto itself:

- Soweto Online is a geographical-based information-sharing portal.[23]

- Soweto Internet Radio is a digital media network company established in 2008.

- Soweto TV is a community television channel, available on DStv channel 251.

- The Sowetan newspaper has a readership of around 1.6 million.[24]

- Kasibiz Mahala is a free community magazine that promotes local small businesses established in 2012.

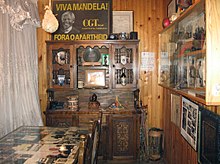

Museums, monuments and memorials

- Hector Pieterson Museum, Orlando West

- Nelson Mandela National Museum, Orlando West

- Regina Mundi church, Rockville

Music

Soweto is credited as one of the founding places for Kwaito and Kasi Rap, which is a style of hip-hop specific to South Africa.[25][26] This form of music, which combined many elements of house music, American hip-hop, and traditional African music, became a strong force amongst black South Africans.

Sport

Football (soccer)

Soweto is home to two soccer teams that play for the top South African football league: the Kaizer Chiefs and the Moroka Swallows. Another club, the Orlando Pirates, originated from Soweto but moved to Parktown. Both the Chiefs and the Pirates feud in the rivalry known as the Soweto derby.

Events

- The Soweto Open tennis tournament, part of the Challenger Tour is annually hosted in Soweto.

- The annual Soweto marathon is run over a 42.2-kilometre (26.2 mi) course through Soweto.

Festivals

The Soweto Wine Festival was started in 2004. The three-night festival is hosted at the University of Johannesburg's Soweto Campus on Chris Hani Road in the first weekend of September. Organised by the Cape Wine Academy, the festival attracts over 6000 wine enthusiasts, over 100 of South Africa's finest wineries and well over 900 fine wines.

Stadiums

- FNB Stadium, South Africa's largest stadium; home ground of both the national team and the Kaizer Chiefs

- Eldorado Park Stadium

- Dobsonville Stadium, home ground of Moroka Swallows

- Jabavu Stadium

- Noordgesig Stadium

- Orlando Stadium, home ground of Orlando Pirates

- Meadowlands Stadium

Suburbs

By 2003 the Greater Soweto area consisted of 87 townships grouped together into Administrative Regions 6 and 10 of Johannesburg.[27]

Estimates of how many residential areas make up Soweto itself vary widely. Some counts say that Soweto comprises 29 townships,[28] whilst others find 34.[29] The differences may be due to confusion arising from the merger of adjoining townships (such as Lenasia and Eldorado Park) with those of Soweto into Regions 6 and 10. The total number also depends on whether the various "extensions" and "zones" are counted separately, or as part of one main suburb. The 2003 Regional Spatial Development Framework arrived at 87 names by counting various extensions (e.g. Chiawelo's 5) and zones (e.g. Pimville's 7) separately. The City of Johannesburg's website groups the zones and extensions together to arrive at 32, but omits Noordgesig and Mmesi Park.[citation needed]

The list below provides the dates when some of Soweto's townships were established, along with the probable origins or meanings of their names, where available:

| Name | Established | Origin of name |

|---|---|---|

| Braamfischerville | ||

| Tshiawelo | 1956 | "Place of Rest" (Venda) |

| Diepkloof | ||

| Dlamini | 1956 | Unknown, Nguni family name. Michael Mabaso also comes from here. This is a township with of a working class population who travel by train to work. |

| Dobsonville | including Dobsonville Gardens | |

| Doornkop | "Hill of Thorns" (Afrikaans) | |

| Dube | 1948 | Named for John Langalibalele Dube (1871–1946), educator,[30] newspaper founder, and the first ANC president (1912–17)[31] |

| Emdeni | 1958 | "A border, last township before Mogale City (then Krugersdorp Municipality)" (Xhosa), including extensions |

| Greenvillage | ||

| Jabavu | 1948 | Named for Davidson Don Tengo Jabavu (1885–1959), educator and author |

| Jabulani | 1956 | "Rejoice" (Zulu) |

| Klipspruit | 1904 | "Rocky Stream" (Afrikaans), originally a farm. |

| Kliptown | " Rocky Town", Constructed from Afrikaans for rock (klip), and the English word "town". | |

| Lakeside | ||

| Mapetla | 1956 | Someone who is angry (Setswana) |

| Meadowlands | Also nicknamed "Ndofaya" | |

| Mmesi Park | Sotho name for somebody who burns things on fire | |

| Mofolo | 1954 | Named for Thomas Mofolo (1876–1948), Sotho author, translator, and educator |

| Molapo | 1956 | Name of a Basotho tribe, sotho name for fetique |

| Moletsane | 1956 | Name of a Batuang chief |

| Moroka | 1946 | Named for Dr James Sebe Moroka (1891–1985),[32] later ANC president (1949–52) during the 1952 Defiance Campaign |

| Naledi | 1956 | "Star" (Sotho/Pedi/Tswana), originally Mkizi |

| Noordgesig | "North View" (Afrikaans) | |

| Orlando | 1932 | Named for Edwin Orlando Leake (1860–1935), chairman of the Non-European Affairs Department (1930–31), Johannesburg mayor (1925–26) |

| Phefeni | ||

| Phiri | 1956 | "Hyena" (Sotho/Tswana) |

| Pimville | 1934 | Named for James Howard Pim, councillor (1903–07), Quaker[citation needed], philanthropist, and patron of Fort Hare Native College [citation needed]; originally part of Klipspruit |

| Power Park | In the vicinity of the power station | |

| Protea Glen | Unknown (The protea is South Africa's national flower) | |

| Protea North | ||

| Protea South | ||

| Senaoane | 1958 | Named for Solomon G Senaoane (−1942), first sports organiser in the Non-European Affairs Department |

| Tladi | 1956 | "Lightning" (Sotho) |

| Zola | 1956 | "Calm" (Zulu/Xhosa) |

| Zondi | 1956 | Unknown family name (Zulu) |

Other Soweto townships include Phomolong and Snake Park[citation needed]

Economy

Many parts of Soweto rank among the poorest in Johannesburg, although individual townships tend to have a mix of wealthier and poorer residents. In general, households in the outlying areas to the northwest and southeast have lower incomes, while those in southwestern areas tend to have higher incomes.

The economic development of Soweto was severely curtailed by the apartheid state, which provided very limited infrastructure and prevented residents from creating their own businesses. Roads remained unpaved, and many residents had to share one tap between four houses, for example. Soweto was meant to exist only as a dormitory town for black Africans who worked in white houses, factories, and industries. The 1957 Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act and its predecessors restricted residents between 1923 to 1976 to seven self-employment categories in Soweto itself. Sowetans could operate general shops, butcheries, eating houses, sell milk or vegetables, or hawk goods. The overall number of such enterprises at any time were strictly controlled. As a result, informal trading developed outside the legally-recognized activities.[4]

By 1976 Soweto had only two cinemas and two hotels, and only 83% of houses had electricity. Up to 93% of residents had no running water. Using fire for cooking and heating resulted in respiratory problems that contributed to high infant mortality rates (54 per 1,000 compared to 18 for whites, 1976 figures.[4]

The restrictions on economic activities were lifted in 1977, spurring the growth of the taxi industry as an alternative to Soweto's inadequate bus and train transport systems.[4]

In 1994 Sowetans earned on average almost six and a half times less than their counterparts in wealthier areas of Johannesburg (1994 estimates). Sowetans contribute less than 2% to Johannesburg's rates.[citation needed] Some Sowetans remain impoverished, and others live in shanty towns with little or no services. About 85% of Kliptown comprises informal housing.[citation needed] The Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee argues that Soweto's poor are unable to pay for electricity. The committee believes that the South African government's privatization drives will worsen the situation. Research showed that 62% of residents in Orlando East and Pimville were unemployed or pensioners.[33]

There have been signs recently indicating economic improvement. The Johannesburg City Council began to provide more street lights and to pave roads. Private initiatives to tap Sowetans' combined spending power of R4.3 billion were also planned[citation needed], including the construction of Protea Mall, Jabulani Mall, the development of Maponya Mall, an upmarket hotel in Kliptown, and the Orlando Ekhaya entertainment centre. Soweto has also become a centre for nightlife and culture.

In popular culture

Songs alluding to Soweto

Clarence Carter Has a song called "The Girl From Soweto" or "Where did the girl go, from Soweto."

Soweto is mentioned in the song Burden of Shame from the British band UB40 on their 1980 album Signing off.

Singer–songwriter Joe Strummer, formerly of The Clash, referenced Soweto in his solo album Streetcore (song: "Arms Aloft"), as well as in The Clash's track, "Where You Gonna Go (Soweto)", found on the album London Calling (Legacy Edition).[34]

The UK music duo Mattafix have a song called "Memories Of Soweto" on their 2007 album Rhythm & Hymns.

Soweto is mentioned in the anti-apartheid song "Gimme Hope Jo'anna" by Eddy Grant. The line "While every mother in a black Soweto fears the killing of another son" refers to police brutality during apartheid.

Miriam Makeba's song: "Soweto Blues".

Dr. Alban's song "Free Up Soweto" was included in the 1994 album Look Who's Talking.

Mexican group Tijuana No! recorded the song "Soweto" for their first album "No". In reference to the city and the movements.

It is also the name of a song by the rap group Hieroglyphics.

American band Vampire Weekend refers to its own musical style, a blend of indie rock and pop with African influences, as "Upper West Side Soweto", based on the same description of Paul Simon's album Graceland.

It is the title of the opening track of the album "Joined at the Hip" by Bob James and Kirk Whalum.

Fiction and cinema

The 1976 uprising was depicted in the 1989 film A Dry White Season, which starred Donald Sutherland, Marlon Brando and Susan Sarandon as white South Africans pursuing justice for the deaths of black Soweto residents which followed the demonstrations.

The marches by students in Soweto are briefly mentioned in a novel by Linzi Glass named Ruby Red, which was nominated for the Carnegie Medal in 2008. Soweto is also mentioned in the novel, Waiting for the Rain by Sheila Gordon.

Soweto was characterised in the 2003 American film Stander. The film presented the story of Andre Stander, a rogue police captain who sympathised with the state of apartheid and its corruption by becoming a bank thief. The Soweto uprising riots provided Stander's breaking point in the film.

In 2006, Sara Blecher and Rimi Raphoto made the popular documentary Surfing Soweto, about young kids "surfing" on the rooves of Soweto trains and the social problem this represents.

The 2009 film District 9 was shot in Soweto, specifically Tshiawelo.[35] The plot involves a species of aliens who arrive on Earth in a starving and helpless condition, seeking aid. The originally benign attempts to aid them turn increasingly oppressive due to the overwhelming numbers of aliens and the cost of maintaining them, and to increasing xenophobia on the part of humans who treat the intelligent and sophisticated aliens like animals while taking advantage of them for personal and corporate gain. The aliens are housed in shacks in a slum-like concentration camp called "District 9", which is in fact modern-day Soweto; an attempt to relocate the aliens to another camp leads to violence and a wholesale slaughter by South African mercenary security forces (a reference to historical events in "District Six", a mostly Coloured neighborhood subjected to forced segregation during the apartheid years). The parallels to apartheid South Africa are obvious but not explicitly remarked on in the film.

Famous Sowetans

Native Sowetans

Soweto is the birthplace of:

- Frank Chikane (born 1951), anti-apartheid activist and lifelong resident

- Bonginkosi Dlamini, aka" Zola", poet, actor, and musician

- Morgan Gould (born 1983), Association football player who plays for Supersport United F.C.

- Doctor Khumalo (born 1967), football player

- Bakithi Kumalo, bass guitar player.

- Jack Lerole musician, famous for penny whistle performance

- Kgosi Letlape (born 1959), South Africa's first black ophthalmologist

- Lebo M., composer

- Mandoza (born 1978), kwaito musician

- Richard Maponya businessman, anti-apartheid activist

- Teko Modise footballer

- Kaizer Motaung (born 16 October 1944), is founder and chairman of Kaizer Chiefs Football Club.

- Lucas Radebe (born 1969), former Leeds United and national team captain

- Cyril Ramaphosa (born 1952), lawyer, trade union leader, activist, politician and businessman

- Mosa Sono (born 1961), bishop and founder of Grace Bible Church International

- Tokyo Sexwale (born 1953), businessman and former politician, anti-apartheid activist, and political prisoner

- Jomo Sono (born 1955), a South African football club owner and coach and a former star soccer player

- Siphiwe Tshabalala (born 1984) South Africa footballer who plays for Kaizer Chiefs Football Club.

- Dire Thomas (born 1967) Optometrist, universal health coverage activist, social entrepreneur and founder of Premier Optical

- Khanyi Mbau Actress and Television personality born 1985 and raised in Mofolo.

- Teboho MacDonald Mashinini, (born 27 January 1957 - 1990), was the primary student leader of the June 1976 Soweto Uprising, that spread across South Africa.

- Trevor Noah (born 1984), South African comedian, TV and radio host, actor, and host of The Daily Show.

Other residents

- Gibson Kente (1932–2004), playwright.

- Irvin Khoza (born 27 January 1948) is a South African football administrator and Chairman of Orlando Pirates.

- Aggrey Klaaste (1940–2004), newspaper journalist and editor.

- Ali BaeBae Lerefolo (born 1940), Scriptwriter, actor, theater performer

- Nelson Mandela (1918-2013) spent many years living in Soweto. His Soweto home in Orlando is currently a major tourist attraction.

- Lilian Ngoyi (1911–1980), anti-apartheid activist, who spent 18 years under house arrest in Mzimhlope.

- Steven Pienaar (born 1982), Everton F.C. and national team football player

- Hector Pieterson (1964–1976), the first student to be killed during the 1976 uprising in Soweto. A picture where the dying Hector is carried away by a man became a famous press photo. Today a memorial and museum named after him in Orlando West reminds of the 1976 Student Uprising.

- Percy Qoboza (1938–1988), newspaper journalist and editor.

- Gerard Sekoto (1913–1993), artist who lived in Kliptown before emigrating to France in 1947.[36]

- Desmond Tutu (born 1931), cleric and activist who rose to worldwide fame during the 1980s, through his opposition to apartheid.

- Lloyd Thomas Snr (born 1990) Musician, rapper, actor and record producer

Other interest

Well-known artists from Soweto, besides those mentioned above, include:

- The Soweto Gospel Choir. Songs and interview from NPR's All Things Considered Soweto Gospel Choir: 'Voices from Heaven', 4 February 2005.

- Soweto String Quartet

- Soweto Melodic Voices, the youth choir selected to sing at the 2009 Confederations Cup. It has built its name in UK on Fringe festival in Edinburgh Scotland.

Films that include Soweto scenes:

- Tau ya Soweto (2005).

- Sarafina (1992).

- Hijack stories (2000)

See also

- The World (South African newspaper)

- Region 6 (Johannesburg)

- Region 1995 (Johannesburg)

- Soweto riots

- Norweto

- Stompie Moeketsi

References

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Soweto". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ Pirie, G.H. Letters, words, worlds: the naming of Soweto. African Studies, 43 (1984), 43–51.

- ^ a b c d e f Carole Rakodi, ed. (1997). "5 Johannesburg: A city and metropolitan area in transformation". The urban challenge in Africa: Growth and management of its large cities. Vol. II The "mega-cities" of Africa. United Nations University Press. ISBN 92-808-0952-0. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ a b c "Chronology of events in the making of Soweto". City of Johannesburg. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

- ^ "THE STRUGGLE FOR A PLACE IN THE CITY". SAHistory. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "James "Sofasonke" Mpanza | South African History Online". Sahistory.org.za. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "The Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, South Africa | The Best Hospital In South Africa - Contact Details (Address, Phone Numbers, Email Address) and Map". Chrishanibaragwanathhospital.co.za. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- ^ "Just Another Day at the World's Biggest Hospital". National Public Radio. 1 December 2003. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "Tembisile 'Chris' Hani". SAHistory. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Soweto Uprising, africanhistory.about.com

- ^ David Grinker, Boris Gorelik (ed) (2014). Inside Soweto: Memoir of an Official 1960s-1980s. Johannesburg: Eastern Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-29186-599-8.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "Population of Soweto, South Africa". mongabay.com.

- ^ [1], Census 2011 — Main Place "Soweto"

- ^ [2], Census 2001 — Main Place "Soweto"

- ^ a b "Climate: Soweto - Climate graph, Temperature graph, Climate table". Climate-Data.org. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "West Wits". Metrorail (South Africa). Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "R360m 'Nasweto' highway to be completed by year-end". Engineering News (Creamer Media). 26 June 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "Bara taxi rank set for major upgrade". City of Johannesburg. 19 February 2003. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "16 000 commuters use Rea Vaya daily". SABC. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ da Silva, M & Pirie, G.H. Hostels for African migrants in greater Johannesburg. GeoJournal, 12 (1986), 173–182.

- ^ [3] Archived 2013-07-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Visit the Soweto Online Portal".

- ^ "Sowetan introduces jobs online". 17 January 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Magubane, Zine. "Globalization and Gangster Rap: Hip Hop in the Post-Apartheid City", in: Basu, Dipannita & Lemelle, Sidney J. (eds.) (2006) The Vinyl Ain’t Final: Hip Hop and the Globalization of Black Popular Culture. London: Pluto Press; pp. 208–29

- ^ Basu, Dipannita. "The Vinyl Ain't Final". Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- ^ "Regional Spatial Development Framework" (PDF). City of Johannesburg. June 2003. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "Soweto". saweb. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "Background to the study area: Soweto" (PDF). University of Pretoria. 2004. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ Millard, J. A. (1999). "Dube, John Langalibalele (Mafukuzela)". UNISA. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "John Langalibalele Dube". African National Congress. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Dr James Sebe Moroka". SAHistory. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "The Soweto Electricity Crisis Committee" (PDF). University of KwaZulu-Natal. 2004. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "London Calling (Legacy Edition)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ "The real District 9". Mail & Guardian. 5 September 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Davie, Lucille (1 November 2004). "Gerard Sekoto's 'illustrious album'". Retrieved 16 November 2009.

Bibliography

- Philip Bonner and Lauren Segal (1998). Soweto: A History. South Africa: Maskew Miller Longman. ISBN 0-636-03033-4.

- Dumesani Ntshangase, Gandhi Malungane, Steve Lebelo, Elsabe Brink, Sue Krige (2001). Soweto, 16 June 1976. South Africa: Kwela Books. ISBN 978-0-7957-0132-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Glaser, Clive (2000). Bo Tsotsi – The Youth Gangs of Soweto. United Kingdom: James Currey. ISBN 978-0-85255-640-5.

- Grinker, David (2014). Inside Soweto: Memoir of an Official 1960s-1980s. Johannesburg: Eastern Enterprises. ISBN 978-1-29186-599-8.

- Holland, Heidi (1995). Born in Soweto – Inside the Heart of South Africa. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-024446-5.

- Hopkins, Pat (1999). The Rocky Rioter Teargas Show. Cape Town: Zebra. ISBN 1-86872-342-9.

- Stephen Laufer, Matada Tsedu (2007). Soweto – A South African Legend. Germany: Arnoldsche. ISBN 978-3-89790-013-4.

- Tessendorf (1989). Along the Road to Soweto: A Racial History of South Africa. Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-31401-9.

External links

Soweto travel guide from Wikivoyage

Soweto travel guide from Wikivoyage- Soweto uprisings.com, an extensive map mashup with info on the events on 16