British Empire in World War II

When the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939 at the start of World War II, it controlled to varying degrees numerous crown colonies, protectorates, and India. It also maintained strong political ties to four of the five independent Dominions—Australia, Canada, South Africa, and New Zealand[a]—as co-members (with the UK) of the British Commonwealth.[b] In 1939 the British Empire and the Commonwealth together comprised a global power, with direct or de facto political and economic control of 25% of the world's population, and of 30% of its land mass.[3]

The contribution of the British Empire and Commonwealth in terms of manpower and materiel was critical to the Allied war-effort. From September 1939 to mid-1942, the UK led Allied efforts in multiple global military theatres. Commonwealth, Colonial and Imperial Indian forces, totalling close to 15 million serving men and women, fought the German, Italian, Japanese and other Axis armies, air-forces and navies across Europe, Africa, Asia, and in the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic, Indian, Pacific and Arctic Oceans. Commonwealth forces based in Britain operated across Northwestern Europe in the effort to slow or stop Axis advances. Commonwealth airforces fought the Luftwaffe to a standstill over Britain, and Commonwealth armies defeated Italian forces in East Africa and North Africa and occupied several overseas colonies of German-occupied European nations. Following successful engagements against Axis forces, Commonwealth troops invaded and occupied Libya, Italian Somaliland, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Iceland, the Faroe Islands, and Madagascar.[4]

The Commonwealth defeated, held back or slowed the Axis powers for three years while mobilizing its globally-integrated economy, military, and industrial infrastructure to build what became, by 1942, the most extensive military apparatus of the war. These efforts came at the cost of 150,000 military deaths, 400,000 wounded, 100,000 prisoners, over 300,000 civilian deaths, and the loss of 70 major warships, 39 submarines, 3,500 aircraft, 1,100 tanks and 65,000 vehicles. During this period the Commonwealth built an enormous military and industrial capacity. Britain became the nucleus of the Allied war-effort in Western Europe, and hosted governments-in-exile in London to rally support in occupied Europe for the Allied cause. Canada delivered almost $4 billion in direct financial aid to the United Kingdom, and Australia and New Zealand began[when?] shifting to domestic production[clarification needed] to provide material aid to US forces in the Pacific.[citation needed] Following the US entry into the war in December 1941, the Commonwealth and the United States coordinated their military efforts and resources globally. As the scale of the US military involvement and industrial production increased, the US undertook command in many theatres, relieving Commonwealth forces for duty elsewhere, and expanding the scope and intensity of Allied military efforts.[5] Co-operation with the Soviet Union also developed. However, it proved difficult to co-ordinate the defence of far-flung colonies and Commonwealth countries from simultaneous attacks by the Axis powers. In part this difficulty was exacerbated by disagreements over priorities and objectives, as well as over the deployment and control of joint forces.

Although the British Empire emerged from the war as one of the primary victors, regaining all colonial territories that had been lost during the conflict, it had become financially, militarily and logistically exhausted. The British Empire's position as a global superpower was supplanted by the United States, and Britain hitherto no longer played as great of a role in international politics as it had previously done so. Stoked by the war, rising nationalist sentiments in British colonies, in particular those in Africa and Asia, led to the gradual dissolution of the British Empire during the second half of the 20th century through decolonisation.[6][7]

Pre-war plans for defence

[edit]From 1923, defence of British colonies and protectorates in East Asia and Southeast Asia was centred on the "Singapore strategy". This made the assumption that Britain could send a fleet to its naval base in Singapore within two or three days of a Japanese attack, while relying on France to provide assistance in Asia via its colony in Indochina and, in the event of war with Italy, to help defend British territories in the Mediterranean.[8] Pre-war planners did not anticipate the fall of France: Nazi occupation, the loss of control over the Channel, and the employment of French Atlantic ports as forward bases for U-boats directly threatened Britain itself, forcing a significant reassessment of naval defence priorities.

During the 1930s, a triple threat emerged for the British Commonwealth in the form of militaristic governments in Germany, Italy, and Japan.[9] Germany threatened Britain itself, while Italy and Japan's imperial ambitions looked set to clash with the British imperial presence in the Mediterranean and East Asia respectively. However, there were differences of opinion within the UK and the Dominions as to which posed the most serious threat, and whether any attack would come from more than one power at the same time.

Declaration of war against Germany

[edit]

On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Two days later, on 3 September, after a British ultimatum to Germany to cease military operations was ignored, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Britain's declaration of war automatically committed India, the Crown colonies, and the protectorates, but the 1931 Statute of Westminster had granted autonomy to the Dominions so each decided their course separately.

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies immediately joined the British declaration on 3 September, believing that it applied to all subjects of the Empire and Commonwealth. New Zealand followed suit simultaneously, at 9.30 pm on 3 September (local time), after Peter Fraser consulted the Cabinet; although as Chamberlain's broadcast was drowned by static, the Cabinet (led by Fraser as Prime Minister Michael Savage was terminally ill) delayed until the Admiralty announced to the fleet a state of war, then backdated the declaration to 9.30 pm. South Africa took three days to make its decision (on 6 September), as the Prime Minister General J. B. M. Hertzog favoured neutrality but was defeated by the pro-war vote in the Union Parliament, led by General Jan Smuts, who then replaced Hertzog. Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King declared support for Britain on the day of the British declaration, but also stated that it was for Parliament to make the formal declaration, which it did so one week later on 10 September. Ireland, though still a member of the Commonwealth, severed its legal ties as a dominion in 1937[10] and chose to remain neutral throughout the war.[11]

Empire and Commonwealth contribution

[edit]

While the war was initially intended to be limited, resources were mobilized quickly, and the first shots were fired almost immediately. Just hours after the Australian declaration of war, a gun at Fort Queenscliff fired across the bows of a ship as it attempted to leave Melbourne without required clearances.[12] On 10 October 1939, an aircraft of No. 10 Squadron RAAF based in England became the first Commonwealth air force unit to go into action when it undertook a mission to Tunisia.[13] The first Canadian convoy of 15 ships bearing war goods departed Halifax just six days after the nation declared war, with two destroyers HMCS St. Laurent and HMCS Saguenay.[14] A further 26 convoys of 527 ships sailed from Canada in the first four months of the war,[15] and by 1 January 1940 Canada had landed an entire division in Britain.[16] On 13 June 1940 Canadian troops deployed to France in an attempt to secure the southern flank of the British Expeditionary Force in Belgium. As the fall of France grew imminent, Britain looked to Canada to rapidly provide additional troops to strategic locations in North America, the Atlantic and Caribbean. Following the Canadian destroyer already on station from 1939, Canada provided troops from May 1940 to assist in the defence of the British Caribbean colonies, with several companies serving throughout the war in Bermuda, Jamaica, the Bahamas and British Guiana. Canadian troops were also sent to the defence of the colony of Newfoundland, on Canada's east coast, the closest point in North America to Germany. Fearing the loss of a land link[clarification needed] to the British Isles, Canada was also requested to occupy Iceland, which it did from June 1940 to the spring of 1941, following the initial British invasion.[17]

From mid-June 1940, following the rapid German invasions and occupations of Poland, Denmark, Norway, France, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, the British Commonwealth was the main opponent of Germany and the Axis, until the entry into the war of the Soviet Union in June 1941. During this period Australia, India, New Zealand and South Africa provided dozens of ships and several divisions for the defence of the Mediterranean, Greece, Crete, Lebanon and Egypt, where British troops were outnumbered four to one by the Italian armies in Libya and Ethiopia.[18] Canada delivered a further 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, pilots for two air squadrons, and several warships to Britain to face a possible invasion from the continent.

In December 1941, Japan launched, in quick succession, attacks on British Malaya, the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, and Hong Kong.

Substantial financial support was provided by Canada to the UK and Commonwealth dominions, in the form of over $4 billion in aid through the Billion Dollar Gift and Mutual Aid and the War Appropriation Act. Over the course of the war over 1.6 million Canadians served in uniform (out of a prewar population of 11 million), in almost every theatre of the war, and by war's end the country had the third-largest navy and fourth-largest air force in the world.[citation needed] By the end of the war, almost a million Australians had served in the armed forces (out of a population of under 7 million), whose military units fought primarily in Europe, North Africa, and the South West Pacific.

The British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (also known as the "Empire Air Training Scheme") was established by the governments of Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK resulting in:

- joint training at flight schools in Canada, South Africa, Southern Rhodesia, Australia and New Zealand;[19]

- formation of new squadrons of the Dominion air forces, known as "Article XV squadrons" for service as part of Royal Air Force operational commands, and;

- in practice, the pooling of RAF and Dominion air force personnel, for posting to both RAF and Article XV squadrons.

Finances

[edit]Britain borrowed everywhere it could and made heavy purchases of munitions and supplies in India and Canada during the war, as well as other parts of the Empire and neutral countries. Canada also made gifts. Britain's sterling balances around the world amounted to £3.4 billion in 1945 or the equivalent of about $US 200 billion in 2016 dollars.[c]However, Britain treated this as a long-term loan with no interest and no specified repayment date. Just when the money would be made available by London was an issue, for the British treasury was nearly empty by 1945.[20]

Crisis in the Mediterranean

[edit]

In June 1940, France surrendered to invading German forces, and Italy joined the war on the Axis side, causing a reversal of the Singapore strategy. Winston Churchill, who had replaced Neville Chamberlain as British Prime Minister the previous month (see Norway debate), ordered that the Middle East and the Mediterranean were of a higher priority than the Far East to defend.[21] Australia and New Zealand were told by telegram that they should turn to the United States for help in defending their homeland should Japan attack:[22]

Without the assistance of France we should not have sufficient forces to meet the combined German and Italian navies in European waters and the Japanese fleet in the Far East. In the circumstances envisaged, it is most improbable that we could send adequate reinforcements to the Far East. We should therefore have to rely on the United States of America to safeguard our interests there.[23]

Commonwealth forces played a major role in North and East Africa following Italy's entry to the war, participating in the invasion of Italian Libya and Somaliland, but were forced to retreat after Churchill diverted resources to Greece and Crete.[24]

Fall of Singapore

[edit]

The Battle of Singapore was fought in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II when the Japanese Empire invaded British Malaya and its stronghold of Singapore. Singapore was the major British military base in South East Asia and nicknamed the "Gibraltar of the East". The fighting in Singapore lasted from 31 January 1942 to 15 February 1942. It followed a humiliating naval engagement in December 1941 in which two British capital ships were sunk.

It resulted in the fall of Singapore to the Japanese, and the largest surrender of British-led military personnel in history.[25] About 80,000 British, Australian and Indian troops became prisoners of war, joining 50,000 taken by the Japanese in the Malayan campaign. Britain's Prime Minister Winston Churchill called the ignominious fall of Singapore to the Japanese the "worst disaster" and "largest capitulation" in British history.[26]

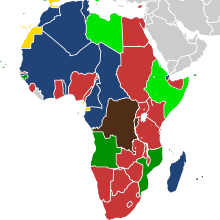

Africa

[edit]

Africa was a large continent whose geography gave it strategic importance during the war. North Africa was the scene of a major campaign against Italy and Germany, which itself included the Tunisian Campaign, the Western Desert Campaign (resulting in tide-turning battles such as those in El Alamein and in Tobruk) and, with large-scale American support, Operation Torch. East Africa was also the scene of a major campaign against Italy which resulted in the liberation of Somalia, Eritrea and most chiefly Ethiopia which had been conquered by the Italian Empire in 1936. The vast geography provided major transportation routes linking the United States to the Middle East and Mediterranean regions. The sea route around South Africa was heavily used even though it added 40 days to voyages that had to avoid the dangerous Suez region. Lend Lease supplies to Russia often came this way. Internally, long-distance road and railroad connections facilitated the British war effort. The Union of South Africa was part of the British Commonwealth of Nations, and had been an independent self-governing country since 1931.[b] British colonies in Africa were administered by the Colonial Office, which frequently implemented a policy of indirect rule. France also held extensive possessions in Africa, but they played a much smaller role in the war, since they were largely tied to Vichy France. Portuguese holdings played a minor role. Italian holdings were the target of successful British military campaigns. The Belgian Congo, and two other Belgian colonies, were major exporters. In terms of numbers and wealth, the British controlled the richest portions of Africa, and made extensive use not only of the geography, but the manpower and the natural resources. Civilian colonial officials made a special effort to upgrade the African infrastructure, promote agriculture, integrate colonial Africa with the world economy, and recruit over a half million soldiers.[27]

Before the war, Britain had made few plans for the utilization of Africa, but it quickly set up command structures. The Army set up the West Africa Command, which recruited 200,000 soldiers. The East Africa Command was created in September 1941 to support the overstretched Middle East Command. The Southern Command was the domain of South Africa. The Royal Navy set up the South Atlantic Command based in Sierra Leone, that became one of the main convoy assembly points. The RAF Coastal Command had major submarine-hunting operations based in West Africa, while a smaller RAF command Dealt with submarines in the Indian Ocean. Ferrying aircraft from North America and Britain was the major mission of the Western Desert Air Force. In addition smaller more localized commands were set up throughout the war.[28]

Before the war, the military establishments were very small throughout British Africa, and largely consisted of white troops, who comprised only two percent of the population outside Africa. As soon as the war began, a large number of new military units were established in Africa, primarily by the Army. The new recruits were a mixture of volunteers and conscripts, who were raised in close cooperation with local tribal leaders. During the war, military pay scales far exceeded what African civilians could earn, especially when food, housing and clothing allowances are included. The largest numbers were in construction units, called Pioneer Units, consisting of over 82,000 African servicemembers. The RAF and Navy also recruited in Africa during the conflict. East Africa provided the largest number of men, over 320,000, chiefly from Kenya, Tanganyika, and Uganda. They did some fighting, a great deal of guard duty, and construction work. 80,000 served in the Middle East. Special care was taken in dealing with African servicemembers not to challenge or overturn the existing social and racial hierarchies which existed in colonial Africa; nevertheless, the soldiers were drilled and train to European standards, given strong doses of propaganda, and learnt leadership and organizational skills that proved essential to the formation of nationalistic and independence movements after 1945. There were minor episodes of discontent among Africans who fought for the British Empire, though the majority remained loyal.[29] Afrikaner nationalism played a major role in South African opposition to joining the war, but pro-German Prime Minister J. B. M. Hertzog resigned in 1939 and was replaced by Jan Smuts, a fellow Afrikaner who was an enthusiastic supporter of South Africa participating in the conflict. Under Smuts' direction, the Union Defence Force raised 340,000 volunteers (of which 190,000 were white, about one-third of all eligible white men in South Africa) to fight in the war.[30]

India

[edit]

The Viceroy Linlithgow declared that India was at war with Germany with no consultations with Indian politicians.[32]

Serious tension erupted over American support for independence for India, a proposition Churchill vehemently rejected.[33] For years Roosevelt had encouraged Britain's disengagement from India. The American position was based on principled opposition to colonialism.[34] The politically active Indian population was deeply divided.[35] One element was so insistent on the expulsion of the British, that it sided with Germany and Japan, and formed the Indian National Army (INA) from Indian prisoners of war. It fought as part of the Japanese invasion of Burma and eastern India. There was a large pacifist element, which rallied to Gandhi's call for abstention from the war; he said that violence in every form was evil.[36] There was a high level of religious tension between the Hindu majority and the Muslims minority. For the first time the Muslim community became politically active, giving strong support for the British war effort. Over 2 million Indians volunteered for military service, including a large Muslim contingent. The British were sensitive to demands of the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, since it needed Muslim soldiers in India and Muslim support all across the Middle East. London used the religious tensions in India as a justification to continue its rule, saying it was needed to prevent religious massacres of the sort that did happen in 1947. The imperialist element in Britain was strongly represented in the Conservative party; Churchill himself had long been its leading spokesman. On the other hand, Attlee and the Labour Party favoured independence and had close ties to the Congress Party. The British cabinet sent Sir Stafford Cripps to India with a specific peace plan offering India the promise of dominion status after the war. Congress demanded independence immediately and the Cripps mission failed. Roosevelt gave support to Congress, sending his representative Louis Johnson to help negotiate some sort of independence. Churchill was outraged, refused to cooperate with Roosevelt on the issue, and threatened to resign as prime minister if Roosevelt pushed too hard. Roosevelt pulled back.[37] In 1942 when the Congress Party launched a Quit India Movement of non-violent civil disobedience, the Raj police immediately arrested tens of thousands of activists (including Gandhi), holding them for the duration. Meanwhile, wartime disruptions caused severe food shortages in eastern India; hundreds of thousands died of starvation. To this day a large Indian element blames Churchill for the Bengal famine of 1943.[38] In terms of the war effort, India became a major base for American supplies sent to China, and Lend Lease operations boosted the local economy. The 2 million Indian soldiers were a major factor in British success in the Middle East. Muslim support for the British war effort proved decisive in the British decision to partition India, forming of the new state of Pakistan.[39]

Victory

[edit]

The Soviet victory on the Eastern Front and the Normandy landings brought about the end of World War II in Europe. The Allies formally accepted the unconditional surrender of the armed forces of Nazi Germany and the end of Adolf Hitler's Third Reich on 8 May 1945. The formal surrender of the occupying German forces in the Channel Islands was not until 9 May 1945. Hitler committed suicide on 30 April during the Battle of Berlin, and so the surrender of Germany was authorized by his replacement, President of Germany Karl Dönitz. The act of military surrender was signed on 7 May in Reims, France, and ratified on 8 May in Berlin, Germany.

The US-led victory over the Empire of Japan brought about the end of World War II in Asia. In the afternoon of 15 August 1945, the surrender of Japan occurred, effectively ending World War II. On this day the initial announcement of Japan's surrender was made in Japan, and because of time zone differences it was announced in the United States, Western Europe, the Americas, the Pacific Islands, and Australia/New Zealand on 14 August 1945. The signing of the surrender document occurred on 2 September 1945.

Aftermath

[edit]By the end of the war in August 1945, British Commonwealth forces were responsible for the civil and/or military administration of a number of non-Commonwealth territories, occupied during the war, including Eritrea, Libya, Madagascar, Iran, Iraq, Lebanon, Italian Somaliland, Syria, Thailand and portions of Germany, Austria and Japan. Most of these military administrations were handed over to old European colonial authorities or to new local authorities soon after the end of the hostilities. Commonwealth forces administered occupation zones in Japan, Germany and Austria until 1955. World War II confirmed that Britain was no longer the great power it had once been, and that it had been surpassed by the United States and Soviet Union on the world stage. Canada, Australia and New Zealand moved within the orbit of the United States. The image of imperial strength in Asia had been shattered by the Japanese attacks, and British prestige there was irreversibly damaged.[40] The price for India's entry to the war had been effectively a guarantee for independence, which came within two years of the end of the war, relieving Britain of its most populous and valuable colony. The deployment of 150,000 Africans overseas from British colonies, and the stationing of white troops in Africa itself led to revised perceptions of the Empire in Africa.[41]

Historiography

[edit]In terms of actual engagement with the enemy, historians have recounted a great deal in South Asia and Southeast Asia, as summarized by Ashley Jackson:

- Terror, mass migration, shortages, inflation, blackouts, air raids, massacres, famine, forced labour, urbanization, environmental damage, occupation [by the enemy], resistance, collaboration – all of these dramatic and often horrific phenomena shaped the war experience of Britain's imperial subjects.[42]

British historians of the Second World War have not emphasized the critical role played by the Empire in terms of money, manpower and imports of food and raw materials.[43] [44] The powerful combination meant that Britain did not stand alone against Germany, it stood at the head of a great but fading empire. As Ashley Jackson has argued," The story of the British Empire's war, therefore, is one of Imperial success in contributing toward Allied victory on the one hand, and egregious Imperial failure on the other, as Britain struggled to protect people and defeat them, and failed to win the loyalty of colonial subjects."[45] The contribution in terms of soldiers numbered 2.5 million men from India, over 1 million from Canada, just under 1 million from Australia, 410,000 from South Africa, and 215,000 from New Zealand. In addition, the colonies mobilized over 500,000 uniformed personnel who serve primarily inside Africa.[46] In terms of financing, the British war budget included £2.7 billion borrowed from the Empire's Sterling Area, And eventually paid back. Canada made C$3 billion in gifts and loans on easy terms.[47]

Military histories of the British Empire's colonies, dominions, mandates and protectorates

[edit]The contributions from individual colonies, dominions, mandates, and protectorates to the war effort were extensive and global. Further information about their involvement can be found in the military histories of the individual colonies, dominions, mandates, and protectorates listed below.

Africa

[edit] Ascension Island

Ascension Island Basutoland

Basutoland Bechuanaland Protectorate

Bechuanaland Protectorate British Cameroons

British Cameroons Gambia

Gambia Gold Coast

Gold Coast Kenya

Kenya Mauritius

Mauritius Nigeria

Nigeria Northern Rhodesia

Northern Rhodesia Nyasaland

Nyasaland Saint Helena

Saint Helena Seychelles

Seychelles Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone Somaliland

Somaliland South Africa

South Africa

Southern Rhodesia

Southern Rhodesia Anglo-Egyptian Sudan

Anglo-Egyptian Sudan Swaziland Protectorate

Swaziland Protectorate Tanganyika

Tanganyika Togoland

Togoland Uganda

Uganda Zanzibar

Zanzibar

Americas

[edit] Bahamas

Bahamas Barbados

Barbados Bermuda

Bermuda Canada

Canada Cayman Islands

Cayman Islands Falkland Islands

Falkland Islands British Guiana

British Guiana British Honduras

British Honduras Jamaica

Jamaica Leeward Islands

Leeward Islands Newfoundland

Newfoundland Trinidad and Tobago

Trinidad and Tobago Turks and Caicos

Turks and Caicos Windward Islands

Windward Islands

East Asia

[edit]Europe

[edit]Middle East

[edit] Aden

Aden Bahrain Protectorate

Bahrain Protectorate Egypt

Egypt Kuwait Protectorate

Kuwait Protectorate Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine Qatar Protectorate

Qatar Protectorate Transjordan

Transjordan Trucial States

Trucial States

Oceania

[edit] Australia

Australia

Fiji

Fiji Gilbert and Ellice Islands

Gilbert and Ellice Islands Nauru

Nauru New Hebrides

New Hebrides New Zealand

New Zealand

Pitcairn Islands

Pitcairn Islands Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands Tonga Protectorate

Tonga Protectorate

South Asia

[edit]Southeast Asia

[edit]See also

[edit]- Diplomatic history of World War II

- Historiography of the British Empire

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

Homefront

[edit]- Australian home front during World War II

- Christmas Island Mutiny and Battle

- Gibraltar evacuation in the Second World War

- British home front during the Second World War

- Japanese occupation of the Andaman Islands

- Japanese occupation of British Borneo

- Japanese occupation of Nauru

- Japanese occupation of Singapore

Major military formations and units

[edit]- List of British Empire corps of the Second World War

- List of British Empire divisions in the Second World War

- List of British Empire brigades of the Second World War

- East Africa Command

- Far East Command

- British Indian Army

- Malaya Command

- Middle East Command

- Persia and Iraq Command

- West Africa Command

- Pacific Fleet

- Eastern Fleet

- Home Fleet

- Mediterranean Fleet

- Reserve Fleet

- Bomber Command

- Ferry Command

- Fighter Command

- RAF Squadrons

- British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

- British Commonwealth Occupation Force

Notes

[edit]- ^ Ireland was technically a dominion but operated largely as an independent republic and remained neutral during the war. Newfoundland, though still called a "Dominion", had ceased self-governing functions and was governed as a colony.

- ^ a b The term "British Commonwealth of Nations", popularised during World War I, became official after the Balfour Declaration in 1926. The Statute of Westminster, passed in 1931, gave legal status to the independence of Australia, Canada, the Irish Free State, Newfoundland, New Zealand and South Africa.[1] After the Statute of Westminster was passed in 1931, the Dominions were "as independent as they wished to be".[2]

- ^ See "Pounds Sterling to Dollars: Historical Conversion of Currency"

References

[edit]- ^ [1] Archived 14 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [2] W. David McIntyre, 1999, "The Commonwealth"; in Robin Winks (ed.), The Oxford History of the British Empire: Volume V: Historiography, Oxford University Press, p. 558-560.

- ^ Leacock 1941, pp. 266–275.

- ^ Jackson 2006.

- ^ Stacey 1970; Edgerton 2011.

- ^ Compare:

Madgwick, Peter James; Steeds, David; Williams, L. J. (1982). Britain Since 1945 (reprint ed.). Hutchinson. p. 283. ISBN 978-0-0914-7371-6. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

The nationalist movements used the political principles of European democracy - self-determination, one man one vote - against European colonialism. Their cause was greatly assisted by the humiliating defeats to which Britain and the other colonial powers were subjected in the Second World War.

- ^ Compare:

Lee, Loyd E., ed. (1997). World War II in Europe, Africa, and the Americas, with General Sources: A Handbook of Literature and Research. Gale virtual reference library. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 468. ISBN 978-0-3132-9325-2. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

[...] the war brought forth a new generation of African politicians who refused to accept the pace of political change laid down by the colonial governments. [...] politicians in British West Africa agitated for self-government [...]. [...] There is a paucity of material about how the Second World War facilitated the decolonization process in individual countries. However, some work has been done on Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia.

- ^ Louis 2006, p. 315.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 284.

- ^ Stewart, Robert B. (July 1938). "Treaty-Making Procedure in the British Dominions". American Journal of International Law. Cambridge University Press. 32 (3): 467–487. Note: from 1937-1949, Ireland's status with regards to the British Empire is hard to define. Though the 1937 amendments abolished the post of Governor General and removed The Crown entirely from having any role in the State's internal governance, certain posts related to foreign policy, such as Irish diplomats continued to receive their accreditation from the monarch and Irish citizens legally remained royal subjects. This confusion was settled after Ireland formally became a recognized Republic in 1949.

- ^ Brown 1998, pp. 307–309.

- ^ McKernan 1983, p. 4.

- ^ Stephens 2006, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Byers 1986, p. 22.

- ^ Hague 2000.

- ^ Byers 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Stacey 1970.

- ^ McIntyre 1977, pp. 336–337; Grey (2008). pp. 156–164.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 310; Jackson 2006, p. 241

- ^ Abreu, Marcelo de Paiva (2015). India as a creditor: sterling balances, 1940–1953 (PDF). Department of Economics, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro.

- ^ Louis 2006, p. 335.

- ^ McIntyre 1977, p. 339.

- ^ Brown 1998, p. 317.

- ^ McIntyre 1977, p. 337.

- ^ Smith, Colin (2006). Singapore Burning: Heroism and Surrender in World War II. Penguin Group. ISBN 0-1410-1036-3.[page needed]

- ^ Churchill, Winston (1986). The Hinge of Fate, Volume 4. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, p. 81. ISBN 0-3954-1058-4

- ^ Jackson 2006, pp. 171–239; Killingray, David; Rathbone, Richard, eds. (1986). Africa and the Second World War.

- ^ Jackson 2006, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Jackson 2006, pp. 180–189.

- ^ Jackson 2006, pp. 240–245.

- ^ "Commonwealth War Graves Commission Report on India 2007–2008" (PDF). Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- ^ Mishra, Basanta Kumar (1979). "India's Response To The British Offer Of August 1940". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 40: 717–719. JSTOR 44142017. Retrieved 2 November 2020.

- ^ Louis, Wm. Roger (1978). Imperialism at Bay: The United States and the Decolonization of the British Empire, 1941–1945.; Buchanan, Andrew N. (2011). "The War Crisis and the Decolonization of India, December 1941 – September 1942: A Political and Military Dilemma". Global War Studies. 8 (2): 5–31. doi:10.5893/19498489.08.02.01.

- ^ Clymer, Kenton J. (1988). "Franklin D. Roosevelt, Louis Johnson, India, and Anticolonialism: Another Look". Pacific Historical Review. 57 (3): 261–284. doi:10.2307/3640705. JSTOR 3640705.

- ^ Khan 2015.

- ^ Herman, Arthur (2008). Gandhi & Churchill: The Epic Rivalry That Destroyed an Empire and Forged Our Age. Bantam Books. pp. 472–539. ISBN 978-0-5538-0463-8. OL 10634350M.

- ^ Kimball, Warren F. (1994). The Juggler: Franklin Roosevelt as Wartime Statesman. Princeton University Press. pp. 134–135. ISBN 0-6910-3730-2.

- ^ Hickman, John (2008). "Orwellian Rectification: Popular Churchill Biographies and the 1943 Bengal Famine". Studies in History. 24 (2): 235–243. doi:10.1177/025764300902400205.

- ^ Rubin, Eric S. (January–March 2011). "America, Britain, and Swaraj: Anglo-American Relations and Indian Independence, 1939–1945". India Review. 10 (1): 40–80. doi:10.1080/14736489.2011.548245.

- ^ McIntyre 1977, p. 341.

- ^ McIntyre 1977, p. 342.

- ^ Jackson, Ashley. The British Empire, 1939–1945. p. 559. in Bosworth & Maiolo 2015

- ^ for survey see Jackson 2006

- ^ For comprehensive coverage and up-to-date bibliography see "The British Empire at War Research Group"

- ^ Jackson, Ashley. The British Empire, 1939–1945. pp. 558–580 (quote p. 559). in Bosworth & Maiolo 2015

- ^ Jackson 2006, p. 563.

- ^ Geyer, Michael; Tooz, Adam, eds. (2015). The Cambridge History of the Second World War. Vol. 3: Total War: Economy, Society and Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-3162-9880-0.

Works cited

[edit]- Bosworth, Richard; Maiolo, Joseph, eds. (2015). The Cambridge History of the Second World War. Vol. 2: Politics and Ideology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-3162-9856-5.

- Brown, Judith (1998). The Twentieth Century, The Oxford History of the British Empire Volume IV. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-1992-4679-3.

- Byers, A. R., ed. (1986). The Canadians at War 1939–45 (2nd ed.). Westmount, QC: The Reader's Digest Association. ISBN 978-0-8885-0145-5. OL 11266235M.

- Edgerton, David (2011). Britain's War Machine: Weapons, Resources, and Experts in the Second World War. Oxford University Press.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The allied convoy system 1939–1945 : its organization, defence and operation. St.Catharines, Ontario: Vanwel. ISBN 978-1-5575-0019-9. OL 12084150M.

- Jackson, Ashley (2006). The British Empire and the Second World War (PDF). London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-8528-5417-1.

- Khan, Yasmin (2015). The Raj at War: A People's History of India's Second World War (India at War: The Subcontinent and the Second World War). Vintage. ISBN 978-0-0995-4227-8. OL 28443197M.

- Leacock, Stephen (1941). Our British empire; its structure, its history, its strength. OL 24216040M.

- Louis, Wm. Roger (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization. I. B. Tauris. ISBN 1-8451-1347-0. OL 8958002M.

- McIntyre, W. Donald (1977). The Commonwealth of Nations. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0792-3. OL 21263204M.

- McKernan, Michael (1983). All in! Australia during the Second World War. Nelson. ISBN 978-0-1700-5946-6. OL 7381398M.

- Stacey, C. P. (1970). Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada, 1939–1945 (PDF). Ottawa: Queen's Printer.

- Stephens, Alan (2006). The Royal Australian Air Force, A History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195555417. OL 28314135M.

Further reading

[edit]- Allport, Alan. Britain at Bay: The Epic Story of the Second World War, 1938–1941 (2020)

- Bousquet, Ben and Colin Douglas. West Indian Women at War: British Racism in World War II (1991) online Archived 22 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Bryce, Robert Broughton (2005). Canada and the cost of World War II. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-2938-0.

- Butler, J.R.M. et al. Grand Strategy (6 vol 1956–60), official overview of the British war effort; Volume 1: Rearmament Policy; Volume 2: September 1939 – June 1941; Volume 3, Part 1: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 3, Part 2: June 1941 – August 1942; Volume 4: September 1942 – August 1943; Volume 5: August 1943 – September 1944; Volume 6: October 1944 – August 1945

- Chartrand, René; Ronald Volstad (2001). Canadian Forces in World War II. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-8417-6302-0.

- Chin, Rachel. War of Words: Britain, France and Discourses of Empire During the Second World War (Cambridge University Press, 2022) online.

- Churchill, Winston. The Second World War (6 vol 1947–51), classic personal history with many documents

- Clarke, Peter. The Last Thousand Days of the British Empire: Churchill, Roosevelt, and the Birth of the Pax Americana (Bloomsbury, 2010) online.

- Clayton, Anthony. The British Empire as a Superpower (Springer, 1986) online.

- Coates, Oliver. "New Perspectives on West Africa and World War Two: Introduction." Journal of African Military History 4.1-2 (2020): 5-39. Focus on Nigeria and Gold Coast (Ghana). online

- Copp, J. T; Richard Nielsen (1995). No price too high: Canadians and the Second World War. McGraw-Hill Ryerson. ISBN 0-0755-2713-8.

- Eccles, Karen E, and Debbie McCollin, edfs. World War II and the Caribbean (2017).

- Hajkowski, Thomas. "The BBC, the empire, and the Second World War, 1939-1945." Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 22.2 (2002): 135-155. https://doi.org/10.1080/01439680220133765

- Harrison, Mark Medicine and Victory: British Military Medicine in the Second World War (2004). ISBN 0-1992-6859-2

- Hastings, Max. Winston's War: Churchill, 1940–1945 (2010)

- Kennedy, Dane. Britain and Empire, 1880-1945 (Routledge, 2014).

- Morton, Desmond (1999). A military history of Canada (4th ed.). Toronto: McClelland and Stewart. ISBN 0-7710-6514-0.

- Mulvey, Paul. The British Empire in World War II. Academic.edu.

- Owino, Meshack. "Kenya and the Second World War: A review of the historiographical landscape." History Compass 19.3 (2021): e12649.

- Raghavan, Srinath. India's War: World War II and the Making of Modern South Asia (2016)

- Stewart, Andrew (2008). Empire Lost: Britain, the Dominions and the Second World War. London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-8472-5244-9.

- Toye, Richard. Churchill's Empire (Pan, 2010).

- Walton, Calder. Empire of secrets: British intelligence, the Cold War, and the twilight of empire (Abrams, 2014).

British Army

[edit]- Allport, Alan. Browned Off and Bloody-Minded: The British Soldier Goes to War, 1939–1945 (Yale UP, 2015)

- Buckley, John. British Armour in the Normandy Campaign 1944 (2004)

- D'Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy: The Unwritten Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign (1983). ISBN 0-0021-7056-6.

- Ellis, L.F. The War in France and Flanders, 1939–1940 (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1953) online

- Ellis, L.F. Victory in the West, Volume 1: Battle of Normandy (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1962)

- Ellis, L.F. Victory in the West, Volume 2: Defeat of Germany (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1968)

- Fraser, David. And We Shall Shock Them: The British Army in World War II (1988). ISBN 978-0-3404-2637-1

- Hamilton, Nigel. Monty: The Making of a General: 1887–1942 (1981); Master of the Battlefield: Monty's War Years 1942–1944 (1984); Monty: The Field-Marshal 1944–1976 (1986).

- Thompson, Julian. The Imperial War Museum Book of the War in Burma 1942–1945 (2004)

Royal Navy

[edit]- Barnett, Corelli. Engage the Enemy More Closely: The Royal Navy in the Second World War (1991)

- Marder, Arthur. Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, vol. 2: The Pacific War, 1942–1945 with Mark Jacobsen and John Horsfield (1990)

- Roskill, S. W. The White Ensign: British Navy at War, 1939–1945 (1960). summary

- Roskill, S. W. War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 1: The Defensive London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1954; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 2: The Period of Balance, 1956; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 1, 1960; War at Sea 1939–1945, Volume 3: The Offensive, Part 2, 1961. online vol 1; online vol 2

Royal Air Force

[edit]- Bungay, Stephen. The Most Dangerous Enemy: The Definitive History of the Battle of Britain (2nd ed. 2010)

- Collier, Basil. Defence of the United Kingdom (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1957) online

- Fisher, David E, A Summer Bright and Terrible: Winston Churchill, Lord Dowding, Radar, and the Impossible Triumph of the Battle of Britain (2005) excerpt online

- Hastings, Max. Bomber Command (1979)

- Hansen, Randall. Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942–1945 (2009)

- Hough, Richard and Denis Richards. The Battle of Britain (1989) 480 pp

- Messenger, Charles, "Bomber" Harris and the Strategic Bombing Offensive, 1939–1945 (1984), defends Harris

- Overy, Richard. The Battle of Britain: The Myth and the Reality (2001) 192 pages excerpt and text search

- Richards, Dennis, et al. Royal Air Force, 1939–1945: The Fight at Odds – Vol. 1 (Her Majesty's Stationery Office 1953), official history; vol 3 online edition

- Shores, Christopher F. Air War for Burma: The Allied Air Forces Fight Back in South-East Asia 1942–1945 (2005)

- Terraine, John. A Time for Courage: The Royal Air Force in the European War, 1939–1945 (1985)

- Verrier, Anthony. The Bomber Offensive (1969), British

- Walker, David. "Supreme air command-the development of royal air force command practice in the second world war." (PhD dissertation, . University of Birmingham, 2018.) online

- Webster, Charles and Noble Frankland, The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany, 1939–1945 (Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1961), 4 vol. Important official British history

- Wood, Derek, and Derek D. Dempster. The Narrow Margin: The Battle of Britain and the Rise of Air Power 1930–40 (1975)

Homefronts

[edit]- Mosby, Ian. Food Will Win the War: The Politics, Culture, and Science of Food on Canada's Home Front (2014)

- Ollerenshaw, Philip. Northern Ireland in the Second World War: Politics, economic mobilisation and society, 1939–45 (2016). online

Historiography and memory

[edit]- Finney, Patrick, ed. Remembering the Second World War (2017) online

- Henderson, Joan C. "Remembering the Second World War in Singapore: Wartime heritage as a visitor attraction." Journal of Heritage Tourism 2.1 (2007): 36–52.

- Joshi, Vandana. "Memory and Memorialisation, Interment and Exhumation, Propaganda and Politics during WWII through the lens of International Tracing Service (ITS) Collections." MIDA Archival Reflexicon (2019): 1-12.

- Summerfield, Penny. Reconstructing women's wartime lives: discourse and subjectivity in oral histories of the Second World War (1998).

External links

[edit]- "The British Empire at War Research Group". For comprehensive coverage and up-to-date bibliography

- Checklist of official histories

- Britain in World War II

- The 11th Day: Crete 1941