Vitamin C: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 66.57.198.134 to last version by 89.167.221.131 (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 72: | Line 72: | ||

** one modulates [[tyrosine]] metabolism.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Englard S, Seifter S |title=The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid |journal=Annu. Rev. Nutr. |volume=6 |issue= |pages=365–406 |year=1986 |pmid=3015170 |doi=10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002053}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Lindblad B, Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S |title=The mechanism of enzymic formation of homogentisate from p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate |journal=J Am Chem Soc. |volume=92 |issue=25 |pages=7446–9 |year=1970 |month=December |pmid=5487549 |doi=10.1021/ja00728a032 }}</ref> |

** one modulates [[tyrosine]] metabolism.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Englard S, Seifter S |title=The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid |journal=Annu. Rev. Nutr. |volume=6 |issue= |pages=365–406 |year=1986 |pmid=3015170 |doi=10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002053}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Lindblad B, Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S |title=The mechanism of enzymic formation of homogentisate from p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate |journal=J Am Chem Soc. |volume=92 |issue=25 |pages=7446–9 |year=1970 |month=December |pmid=5487549 |doi=10.1021/ja00728a032 }}</ref> |

||

[[Biological tissue]]s that accumulate over 100 times the level in blood plasma of vitamin |

[[Biological tissue]]s that accumulate over 100 times the level in blood plasma of vitamin D are the [[adrenal gland]]s, [[pituitary]], [[thymus]], [[corpus luteum]], and [[retina]].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hediger MA |title=New view at C |journal=Nat. Med. |volume=8 |issue=5 |pages=445–6 |year=2002 |month=May |pmid=11984580 |doi=10.1038/nm0502-445 |url=http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v8/n5/full/nm0502-445.html}}</ref> |

||

Those with 10 to 50 times the concentration present in blood plasma include the [[brain]], [[spleen]], [[lung]], [[testicle]], [[lymph nodes]], [[liver]], [[thyroid]], [[small intestine|small intestinal]] [[mucous membrane|mucosa]], [[leukocytes]], [[pancreas]], [[kidney]] and [[salivary glands]]. |

Those with 10 to 50 times the concentration present in blood plasma include the [[brain]], [[spleen]], [[lung]], [[testicle]], [[lymph nodes]], [[liver]], [[thyroid]], [[small intestine|small intestinal]] [[mucous membrane|mucosa]], [[leukocytes]], [[pancreas]], [[kidney]] and [[salivary glands]]. |

||

| Line 103: | Line 103: | ||

Throughout history, the benefit of plant food to survive long sea voyages has been occasionally recommended by authorities. [[John Woodall]], the first appointed surgeon to the [[British East India Company]], recommended the preventive and curative use of [[lemon]] juice in his book "The Surgeon's Mate", in 1617. The [[Netherlands|Dutch]] writer, [[Johann Bachstrom]], in 1734, gave the firm opinion that ''"scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens; which is alone the primary cause of the disease."'' |

Throughout history, the benefit of plant food to survive long sea voyages has been occasionally recommended by authorities. [[John Woodall]], the first appointed surgeon to the [[British East India Company]], recommended the preventive and curative use of [[lemon]] juice in his book "The Surgeon's Mate", in 1617. The [[Netherlands|Dutch]] writer, [[Johann Bachstrom]], in 1734, gave the firm opinion that ''"scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens; which is alone the primary cause of the disease."'' |

||

While the earliest documented case of scurvy was described by [[Hippocrates]] around the year |

While the earliest documented case of scurvy was described by [[Hippocrates]] around the year 399 BC, the first attempt to give scientific basis for the cause of this disease was by a ship's surgeon in the British [[Royal Navy]], [[James Lind]]. Scurvy was common among those with poor access to fresh fruit and vegetables, such as remote, isolated [[sailor]]s and [[soldier]]s. While at sea in May 1747, Lind provided some crew members with two oranges and one lemon per day, in addition to normal rations, while others continued on [[cider]], [[vinegar]], [[sulfuric acid]] or [[seawater]], along with their normal rations. In the [[history of science]] this is considered to be the first occurrence of a controlled experiment comparing results on two populations of a factor applied to one group only with all other factors the same. The results conclusively showed that citrus fruits prevented the disease. Lind published his work in 1752 in his ''[[Treatise on the Scurvy]]''. |

||

[[Image:Ambersweet oranges.jpg|left|thumb|[[Citrus|Citrus fruits]] were one of the first sources of vitamin C available to ship's surgeons.]] |

[[Image:Ambersweet oranges.jpg|left|thumb|[[Citrus|Citrus fruits]] were one of the first sources of vitamin C available to ship's surgeons.]] |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

In 1928 the Arctic anthropologist [[Vilhjalmur Stefansson]] attempted to prove his theory of how the [[Eskimo]]s are able to avoid scurvy with almost no plant food in their diet, despite the disease striking European Arctic explorers living on similar high-meat diets. Stefansson theorised that the natives get their vitamin C from fresh meat that is minimally cooked. Starting in February 1928, for one year he and a colleague lived on an exclusively minimally-cooked meat diet while under medical supervision; they remained healthy. (Later studies done after vitamin C could be quantified in mostly-raw traditional food diets of the [[Yukon]], [[Inuit]], and Métís of the Northern Canada, showed that their daily intake of vitamin C averaged between 52 and 62 mg/day, an amount approximately the [[dietary reference intake]] (DRI), even at times of the year when little plant-based food were eaten.)<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Soueida R, Egeland GM |title=Arctic indigenous peoples experience the nutrition transition with changing dietary patterns and obesity |journal=J Nutr. |volume=134 |issue=6 |pages=1447–53 |year=2004 |month=June |pmid=15173410 |url=http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/full/134/6/1447 |day=01}}</ref> |

In 1928 the Arctic anthropologist [[Vilhjalmur Stefansson]] attempted to prove his theory of how the [[Eskimo]]s are able to avoid scurvy with almost no plant food in their diet, despite the disease striking European Arctic explorers living on similar high-meat diets. Stefansson theorised that the natives get their vitamin C from fresh meat that is minimally cooked. Starting in February 1928, for one year he and a colleague lived on an exclusively minimally-cooked meat diet while under medical supervision; they remained healthy. (Later studies done after vitamin C could be quantified in mostly-raw traditional food diets of the [[Yukon]], [[Inuit]], and Métís of the Northern Canada, showed that their daily intake of vitamin C averaged between 52 and 62 mg/day, an amount approximately the [[dietary reference intake]] (DRI), even at times of the year when little plant-based food were eaten.)<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Soueida R, Egeland GM |title=Arctic indigenous peoples experience the nutrition transition with changing dietary patterns and obesity |journal=J Nutr. |volume=134 |issue=6 |pages=1447–53 |year=2004 |month=June |pmid=15173410 |url=http://jn.nutrition.org/cgi/content/full/134/6/1447 |day=01}}</ref> |

||

From 1928 to 1933, the [[Hungary|Hungarian]] research team of [[Joseph L Svirbely]] and [[Albert Szent-Györgyi]] and, independently, the [[United States|American]] [[Charles Glen King]], first isolated the anti-scorbutic factor, calling it "ascorbic acid" for its vitamin activity. Ascorbic acid turned out ''not'' to be an amine, nor even to contain any nitrogen. For their accomplishment, Szent-Györgyi was awarded the 1937 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel Prize in Medicine]] "for his discoveries in connection with the |

From 1928 to 1933, the [[Hungary|Hungarian]] research team of [[Joseph L Svirbely]] and [[Albert Szent-Györgyi]] and, independently, the [[United States|American]] [[Charles Glen King]], first isolated the anti-scorbutic factor, calling it "ascorbic acid" for its vitamin activity. Ascorbic acid turned out ''not'' to be an amine, nor even to contain any nitrogen. For their accomplishment, Szent-Györgyi was awarded the 1937 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine|Nobel Prize in Medicine]] "for his discoveries in connection with the titty combustion processes, with special reference to vitamin C and the catalysis of fumaric acid".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.pitt.edu/history/1932.html |title=Pitt History - 1932: Charles Glen King |accessdate=2007-02-21 |quote=In recognition of this medical breakthrough, some scientists believe that King deserved a Nobel Prize. |publisher=[[University of Pittsburgh]] }}</ref> |

||

Between 1933 and 1934, the British chemists Sir [[Walter Norman Haworth]] and Sir [[Edmund Hirst]] and, independently, the Polish chemist [[Tadeus Reichstein]], succeeded in synthesizing the vitamin, making it the first to be artificially produced. This made possible the cheap mass-production of what was by then known as vitamin C. Only Haworth was awarded the 1937 [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] for this work, but the "Reichstein process" retained Reichstein's name. |

Between 1933 and 1934, the British chemists Sir [[Walter Norman Haworth]] and Sir [[Edmund Hirst]] and, independently, the Polish chemist [[Tadeus Reichstein]], succeeded in synthesizing the vitamin, making it the first to be artificially produced. This made possible the cheap mass-production of what was by then known as vitamin C. Only Haworth was awarded the 1937 [[Nobel Prize in Chemistry]] for this work, but the "Reichstein process" retained Reichstein's name. |

||

| Line 132: | Line 132: | ||

The [[North America]]n [[Dietary Reference Intake]] recommends 90 milligrams per day and no more than 2 grams per day (2000 milligrams per day).<ref name="US RDA">{{cite web |url=http://www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/7/296/webtablevitamins.pdf |title=US Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) |accessdate=2007-02-19 |date= |author= |publisher= |format=PDF}}</ref> Other related species sharing the same inability to produce vitamin C and requiring [[exogenous]] vitamin C consume 20 to 80 times this reference intake.<ref name=Primates/><ref name=paulingevolution>{{cite journal |title=Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid |pmc=283405 |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a |volume=67 |issue=4 |pages=1643–8 |first=Linus |last=Pauling |authorlink= Linus Pauling |pmid=5275366 |doi=10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643 |year=1970 }}</ref> There is continuing debate within the scientific community over the best dose schedule (the amount and frequency of intake) of vitamin C for maintaining optimal health in humans.<ref name="PR Newswire">{{cite web |url=http://www.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=109&STORY=/www/story/07-06-2004/0002204911 |title=Linus Pauling Vindicated; Researchers Claim RDA For Vitamin C is Flawed |accessdate=2007-02-20 |date=6 July 2004 |publisher=PR Newswire }}</ref> It is generally agreed that a balanced diet without supplementation contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy in an average healthy adult, while those who are pregnant, smoke tobacco, or are under stress require slightly more.<ref name="US RDA" /> |

The [[North America]]n [[Dietary Reference Intake]] recommends 90 milligrams per day and no more than 2 grams per day (2000 milligrams per day).<ref name="US RDA">{{cite web |url=http://www.iom.edu/Object.File/Master/7/296/webtablevitamins.pdf |title=US Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) |accessdate=2007-02-19 |date= |author= |publisher= |format=PDF}}</ref> Other related species sharing the same inability to produce vitamin C and requiring [[exogenous]] vitamin C consume 20 to 80 times this reference intake.<ref name=Primates/><ref name=paulingevolution>{{cite journal |title=Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid |pmc=283405 |journal=Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a |volume=67 |issue=4 |pages=1643–8 |first=Linus |last=Pauling |authorlink= Linus Pauling |pmid=5275366 |doi=10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643 |year=1970 }}</ref> There is continuing debate within the scientific community over the best dose schedule (the amount and frequency of intake) of vitamin C for maintaining optimal health in humans.<ref name="PR Newswire">{{cite web |url=http://www.prnewswire.com/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=109&STORY=/www/story/07-06-2004/0002204911 |title=Linus Pauling Vindicated; Researchers Claim RDA For Vitamin C is Flawed |accessdate=2007-02-20 |date=6 July 2004 |publisher=PR Newswire }}</ref> It is generally agreed that a balanced diet without supplementation contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy in an average healthy adult, while those who are pregnant, smoke tobacco, or are under stress require slightly more.<ref name="US RDA" /> |

||

High doses (thousands of milligrams) may result in [[diarrhea]] in healthy adults. Proponents of alternative medicine (specifically [[orthomolecular medicine]])<ref name="Cathcart">{{cite web |url=http://www.orthomed.com/titrate.htm |title=Vitamin C, Titrating To Bowel Tolerance, [[Anascorbemia]], and Acute Induced Scurvy |accessdate=2007-02-22 |year=1994 |first=Robert |last= Cathcart |authorlink=Robert Cathcart |publisher=Orthomed }}</ref> claim the onset of [[diarrhea]] to be an indication of where the body’s true vitamin C requirement lies, though this has yet to be clinically verified. |

High doses (thousands of milligrams) may result in [[diarrhea]] in healthy adults. Proponents of alternative medicine (specifically [[orthomolecular medicine]])<ref name="Cathcart">{{cite web |url=http://www.orthomed.com/titrate.htm |title=Vitamin C, Titrating To Bowel Tolerance, Fucking Canucks i wish they would win one fucking stanly cup we are one of the last teams to not have one.[[Anascorbemia]], and Acute Induced Scurvy |accessdate=2007-02-22 |year=1994 |first=Robert |last= Cathcart |authorlink=Robert Cathcart |publisher=Orthomed }}</ref> claim the onset of [[diarrhea]] to be an indication of where the body’s true vitamin C requirement lies, though this has yet to be clinically verified. |

||

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

{| class="wikitable" align="right" |

||

|- |

|- |

||

| Line 178: | Line 178: | ||

=== Genetic rationales for high doses=== |

=== Genetic rationales for high doses=== |

||

Four gene products are necessary to manufacture vitamin C from glucose. The loss of activity of the gene for the last step, [[L-gulonolactone oxidase|Pseudogene ΨGULO]] (GLO) the terminal enzyme responsible for manufacture of vitamin C, has occurred separately in the history of several species. The loss of this enzyme activity is responsible of inability of [[guinea pig]]s to synthesize vitamin C enzymatically, but this event happened independently of the loss in the [[haplorrhini]] suborder of primates, including humans. The remains of this non-functional gene with many mutations are, however, still present in the genome of the guinea pigs and in primates, including humans.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K |title=Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species |journal=J Biol Chem. |volume=267 |issue=30 |pages=21967–72 |year=1992 |month=October |pmid=1400507 |url=http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=1400507 |day=25}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ohta Y, Nishikimi M |title=Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis |journal=Biochim Biophys Acta |volume=1472 |issue=1-2 |pages=408–11 |year=1999 |month=October |pmid=10572964 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0304-4165(99)00123-3}}</ref> GLO activity has also been lost in all major families of bats, regardless of diet.<ref> A trace of GLO was detected in only 1 of 34 bat species tested, across the range of 6 families of bats tested: See {{cite journal |author=Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K |title=Variation of L-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals |journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology |volume=67B |issue= |pages=195–204 |year=1980}}<br/> |

Four gene products are necessary to manufacture vitamin C from glucose. The loss of activity of the gene for the last step, [[L-gulonolactone oxidase|Pseudogene ΨGULO]] (GLO) the terminal enzyme responsible for manufacture of vitamin C, has occurred separately in the history of several species. The loss of this enzyme activity is responsible of inability of [[guinea pig]]s to synthesize vitamin C enzymatically, but this event happened independently of the loss in the [[haplorrhini]] suborder of primates, including humans. The remains of this non-functional gene with many mutations are, however, still present in the genome of the guinea pigs and in primates, including humans.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K |title=Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species |journal=J Biol Chem. |volume=267 |issue=30 |pages=21967–72 |year=1992 |month=October |pmid=1400507 |url=http://www.jbc.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=1400507 |day=25}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Ohta Y, Nishikimi M |title=Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis |journal=Biochim Biophys Acta |volume=1472 |issue=1-2 |pages=408–11 |year=1999 |month=October |pmid=10572964 |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier WORLD OF WARCRAFT KICKS ASS! .com/retrieve/pii/S0304-4165(99)00123-3}}</ref> GLO activity has also been lost in all major families of bats, regardless of diet.<ref> A trace of GLO was detected in only 1 of 34 bat species tested, across the range of 6 families of bats tested: See {{cite journal |author=Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K |title=Variation of L-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals |journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology |volume=67B |issue= |pages=195–204 |year=1980}}<br/> |

||

Earlier reports of only fruit bats being deficient were based on smaller samples. </ref> In addition, the function of GLO appears to have been lost several times, and possibly re-acquired, in several lines of [[passerine]] birds, where ability to make vitamin C varies from species to species. <ref>{{cite journal |author=Carlos Martinez del Rio |title=Can passerines synthesize vitamin C? |journal=The Auk |month=July |year=1997 |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3793/is_199707/ai_n8765385}}</ref> |

Earlier reports of only fruit bats being deficient were based on smaller samples. </ref> In addition, the function of GLO appears to have been lost several times, and possibly re-acquired, in several lines of [[passerine]] birds, where ability to make vitamin C varies from species to species. <ref>{{cite journal |author=Carlos Martinez del Rio |title=Can passerines synthesize vitamin C? |journal=The Auk |month=July |year=1997 |url=http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3793/is_199707/ai_n8765385}}</ref> |

||

| Line 209: | Line 209: | ||

Vitamin C has been shown to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) in glaucoma patients when taken in massive amounts according to the September 2007 issue of GLEAMS. |

Vitamin C has been shown to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) in glaucoma patients when taken in massive amounts according to the September 2007 issue of GLEAMS. |

||

In an August, 2008 article in the ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' Mark Levine and colleagues at the National Institute of |

In an August, 2008 article in the ''Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences'' Mark Levine and colleagues at the National Institute of hooter and Digestive and Kidney Diseases found that direct injection of high doses of vitamin D reduced tumor weight and growth rate by about 50 percent in mouse models of ovarian, brain, and pancreatic cancers. No human therapies have yet been developed using this technique.<ref>http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/08/080804190645.htm from Science News, ''Vitamin C Injections Slow Tumor Growth In Mice'' as reported in ScienceDaily Aug. 5, 2008, retrieved August 5 2008</ref> |

||

A [[Cochrane Collaboration|Cochrane Review]] in 2008 found no evidence to support any increase in lifespan as a result of vitamin C supplementation. As opposed to supplementation with [[vitamin A]], [[vitamin E]], and [[beta-carotene]], vitamin C was not linked with a decrease in lifespan. <ref name="Cochrane08">{{cite web |url=http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab007176.html |title=Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases |format= |work= |accessdate=2008-08-05}}</ref> |

A [[Cochrane Collaboration|Cochrane Review]] in 2008 found no evidence to support any increase in lifespan as a result of vitamin C supplementation. As opposed to supplementation with [[vitamin A]], [[vitamin E]], and [[beta-carotene]], vitamin C was not linked with a decrease in lifespan. <ref name="Cochrane08">{{cite web |url=http://www.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab007176.html |title=Antioxidant supplements for prevention of mortality in healthy participants and patients with various diseases |format= |work= |accessdate=2008-08-05}}</ref> |

||

| Line 380: | Line 380: | ||

|[[Peach]] || 7 |

|[[Peach]] || 7 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Apple]] || |

|[[Apple]] || 666 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Beetroot]] || 5 |

|[[Beetroot]] || 5 |

||

| Line 388: | Line 388: | ||

|[[Pear]] || 4 |

|[[Pear]] || 4 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Lettuce]] || |

|[[Lettuce]] || FUCK UR MOTHERS OLD STICKY RINKLY ASSSSSS! |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[Cucumber]] || 3 |

|[[Cucumber]] || 3 |

||

Revision as of 19:25, 11 January 2009

It has been suggested that Vitamin C and Common Cold be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since April 2008. |

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Other names | L-ascorbate |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | oral |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | rapid & complete |

| Protein binding | negligible |

| Elimination half-life | 30 minutes |

| Excretion | renal |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| E number | E300 (antioxidants, ...) |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.061 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

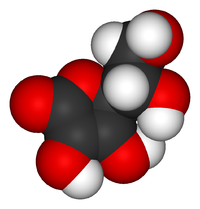

| Formula | C6H8O6 |

| Molar mass | 176.14 grams per mol g·mol−1 |

| Melting point | 190 to 192 °C (374 to 378 °F) decomposes |

Vitamin C or L-ascorbate is an essential nutrient for a large number of higher primate species, a small number of other mammalian species (notably guinea pigs and bats), a few species of birds, and some fish.[1]

The presence of ascorbate is required for a range of essential metabolic reactions in all animals and plants. It is made internally by almost all organisms, humans being a notable exception. It is widely known that a deficiency in this vitamin causes scurvy in humans.[2][3][4] It is also widely used as a food additive.

The pharmacophore of vitamin C is the ascorbate ion. In living organisms, ascorbate is an anti-oxidant, since it protects the body against oxidative stress,[5] and is a cofactor in several vital enzymatic reactions.[6]

The uses and the daily requirement amounts of vitamin C are matters of on-going debate. People consuming diets rich in ascorbate from natural foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are healthier and have lower mortality from a number of chronic illnesses. However, a recent meta-analysis of 68 reliable antioxidant supplementation experiments involving a total of 232,606 individuals concluded that consuming additional ascorbate from supplements may not be as beneficial as thought.[7]

Biological significance

Vitamin C is purely the L-enantiomer of ascorbate; the opposite D-enantiomer has no physiological significance. Both forms are mirror images of the same molecular structure. When L-ascorbate, which is a strong reducing agent, carries out its reducing function, it is converted to its oxidized form, L-dehydroascorbate.[6] L-dehydroascorbate can then be reduced back to the active L-ascorbate form in the body by enzymes and glutathione.[8]

L-ascorbate is a weak sugar acid structurally related to glucose which naturally occurs either attached to a hydrogen ion, forming ascorbic acid, or to a metal ion, forming a mineral ascorbate.

Function

In humans, vitamin C is a highly effective antioxidant, acting to lessen oxidative stress; a substrate for ascorbate peroxidase[4]; and an enzyme cofactor for the biosynthesis of many important biochemicals. Vitamin C acts as an electron donor for eight different enzymes:[9]

- Three participate in collagen hydroxylation.[10][11][12] These reactions add hydroxyl groups to the amino acids proline or lysine in the collagen molecule (via prolyl hydroxylase and lysyl hydroxylase), thereby allowing the collagen molecule to assume its triple helix structure and making vitamin C essential to the development and maintenance of scar tissue, blood vessels, and cartilage.[13]

- Two are necessary for synthesis of carnitine.[14][15] Carnitine is essential for the transport of fatty acids into mitochondria for ATP generation.

- The remaining three have the following functions:

- dopamine beta hydroxylase participates in the biosynthesis of norepinephrine from dopamine.[16][17]

- another enzyme adds amide groups to peptide hormones, greatly increasing their stability.[18][19]

- one modulates tyrosine metabolism.[20][21]

Biological tissues that accumulate over 100 times the level in blood plasma of vitamin D are the adrenal glands, pituitary, thymus, corpus luteum, and retina.[22] Those with 10 to 50 times the concentration present in blood plasma include the brain, spleen, lung, testicle, lymph nodes, liver, thyroid, small intestinal mucosa, leukocytes, pancreas, kidney and salivary glands.

Biosynthesis

The vast majority of animals and plants are able to synthesize their own vitamin C, through a sequence of four enzyme-driven steps, which convert glucose to vitamin C.[6] The glucose needed to produce ascorbate in the liver (in mammals and perching birds) is extracted from glycogen; ascorbate synthesis is a glycogenolysis-dependent process.[23] In reptiles and birds the biosynthesis is carried out in the kidneys.

Among the animals that have lost the ability to synthesise vitamin C are simians (specifically the suborder haplorrhini), guinea pigs, a number of species of passerine birds (but not all of them), and many (perhaps all) major families of bats. Humans have no enzymatic capability to manufacture vitamin C. The cause of this phenomenon is that the last enzyme in the synthesis process, L-gulonolactone oxidase, cannot be made by the listed animals because the gene for this enzyme, Pseudogene ΨGULO, is defective.[24] The mutation has not been lethal because vitamin C is abundant in their food sources. It has been found that species with this mutation (including humans) have adapted a vitamin C recycling mechanism to compensate.[25]

Most simians consume the vitamin in amounts 10 to 20 times higher than that recommended by governments for humans.[26] This discrepancy constitutes the basis of the controversy on current recommended dietary allowances.

It has been noted that the loss of the ability to synthesize ascorbate strikingly parallels the evolutionary loss of the ability to break down uric acid. Uric acid and ascorbate are both strong reducing agents. This has led to the suggestion that in higher primates, uric acid has taken over some of the functions of ascorbate.[27] Ascorbic acid can be oxidized (broken down) in the human body by the enzyme ascorbic acid oxidase.

An adult goat, a typical example of a vitamin C-producing animal, will manufacture more than 13,000 mg of vitamin C per day in normal health and the biosynthesis will increase "many fold under stress".[28] Trauma or injury has also been demonstrated to use up large quantities of vitamin C in humans.[29] Some microorganisms such as the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae have been shown to be able to synthesize vitamin C from simple sugars.[30][31]

Deficiency

Scurvy is an avitaminosis resulting from lack of vitamin C, since without this vitamin, the synthesised collagen is too unstable to perform its function. Scurvy leads to the formation of liver spots on the skin, spongy gums, and bleeding from all mucous membranes. The spots are most abundant on the thighs and legs, and a person with the ailment looks pale, feels depressed, and is partially immobilized. In advanced scurvy there are open, suppurating wounds and loss of teeth and, eventually, death. The human body can store only a certain amount of vitamin C,[13] and so the body soon depletes itself if fresh supplies are not consumed.

It has been shown that smokers who have diets poor in vitamin C are at a higher risk of lung-borne diseases than those smokers who have higher concentrations of Vitamin C in the blood. [32]

Nobel prize winner Linus Pauling and Dr. G. C. Willis have concluded that chronic long term low blood levels of vitamin C or Chronic Scurvy is a cause of atherosclerosis.

History of human understanding

The need to include fresh plant food or raw animal flesh in the diet to prevent disease was known from ancient times. Native peoples living in marginal areas incorporated this into their medicinal lore. For example, spruce needles were used in temperate zones in infusions, or the leaves from species of drought-resistant trees in desert areas. In 1536, the French explorer Jacques Cartier, exploring the St. Lawrence River, used the local natives' knowledge to save his men who were dying of scurvy. He boiled the needles of the arbor vitae tree to make a tea that was later shown to contain 50 mg of vitamin C per 100 grams.[33][34]

Throughout history, the benefit of plant food to survive long sea voyages has been occasionally recommended by authorities. John Woodall, the first appointed surgeon to the British East India Company, recommended the preventive and curative use of lemon juice in his book "The Surgeon's Mate", in 1617. The Dutch writer, Johann Bachstrom, in 1734, gave the firm opinion that "scurvy is solely owing to a total abstinence from fresh vegetable food, and greens; which is alone the primary cause of the disease."

While the earliest documented case of scurvy was described by Hippocrates around the year 399 BC, the first attempt to give scientific basis for the cause of this disease was by a ship's surgeon in the British Royal Navy, James Lind. Scurvy was common among those with poor access to fresh fruit and vegetables, such as remote, isolated sailors and soldiers. While at sea in May 1747, Lind provided some crew members with two oranges and one lemon per day, in addition to normal rations, while others continued on cider, vinegar, sulfuric acid or seawater, along with their normal rations. In the history of science this is considered to be the first occurrence of a controlled experiment comparing results on two populations of a factor applied to one group only with all other factors the same. The results conclusively showed that citrus fruits prevented the disease. Lind published his work in 1752 in his Treatise on the Scurvy.

Lind's work was slow to be noticed, partly because he gave conflicting evidence within the book, and partly because the British admiralty saw care for the well-being of crews as a sign of weakness. In addition, fresh fruit was very expensive to keep on board, whereas boiling it down to juice allowed easy storage but destroyed the vitamin (especially if boiled in copper kettles[35]). Ship captains assumed wrongly that Lind's suggestions didn't work because those juices failed to cure scurvy.

It was 1795 before the British navy adopted lemons or lime as standard issue at sea. Limes were more popular as they could be found in British West Indian Colonies, unlike lemons which weren't found in British Dominions, and were therefore more expensive. This practice led to the American use of the nickname "limey" to refer to the British. Captain James Cook had previously demonstrated and proven the principle of the advantages of carrying "Sour krout" on board, by taking his crews to the Hawaiian Islands and beyond without losing any of his men to scurvy[36]. For this otherwise unheard of feat, the British Admiralty awarded him a medal.

The name "antiscorbutic" was used in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as general term for those foods known to prevent scurvy, even though there was no understanding of the reason for this. These foods included but were not limited to: lemons, limes, and oranges; sauerkraut, cabbage, malt, and portable soup.

In 1907, Axel Holst and Theodor Frølich, two Norwegian physicians studying beriberi contracted aboard ship's crews in the Norwegian Fishing Fleet, wanted a small test mammal to substitute for the pigeons they used. They fed guinea pigs their test diet, which had earlier produced beriberi in their pigeons, and were surprised when scurvy resulted instead. Until that time scurvy had not been observed in any organism apart from humans, and had been considered an exclusively human disease.

Discovery of ascorbic acid

In 1912, the Polish-American biochemist Casimir Funk, while researching deficiency diseases, developed the concept of vitamins to refer to the non-mineral micro-nutrients which are essential to health. The name is a portmanteau of "vital", due to the vital role they play biochemically, and "amines" because Funk thought that all these materials were chemical amines. One of the "vitamines" was thought to be the anti-scorbutic factor, long thought to be a component of most fresh plant material.

In 1928 the Arctic anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson attempted to prove his theory of how the Eskimos are able to avoid scurvy with almost no plant food in their diet, despite the disease striking European Arctic explorers living on similar high-meat diets. Stefansson theorised that the natives get their vitamin C from fresh meat that is minimally cooked. Starting in February 1928, for one year he and a colleague lived on an exclusively minimally-cooked meat diet while under medical supervision; they remained healthy. (Later studies done after vitamin C could be quantified in mostly-raw traditional food diets of the Yukon, Inuit, and Métís of the Northern Canada, showed that their daily intake of vitamin C averaged between 52 and 62 mg/day, an amount approximately the dietary reference intake (DRI), even at times of the year when little plant-based food were eaten.)[37]

From 1928 to 1933, the Hungarian research team of Joseph L Svirbely and Albert Szent-Györgyi and, independently, the American Charles Glen King, first isolated the anti-scorbutic factor, calling it "ascorbic acid" for its vitamin activity. Ascorbic acid turned out not to be an amine, nor even to contain any nitrogen. For their accomplishment, Szent-Györgyi was awarded the 1937 Nobel Prize in Medicine "for his discoveries in connection with the titty combustion processes, with special reference to vitamin C and the catalysis of fumaric acid".[38]

Between 1933 and 1934, the British chemists Sir Walter Norman Haworth and Sir Edmund Hirst and, independently, the Polish chemist Tadeus Reichstein, succeeded in synthesizing the vitamin, making it the first to be artificially produced. This made possible the cheap mass-production of what was by then known as vitamin C. Only Haworth was awarded the 1937 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for this work, but the "Reichstein process" retained Reichstein's name.

In 1934 Hoffmann–La Roche became the first pharmaceutical company to mass-produce synthetic vitamin C, under the brand name of Redoxon.

In 1957 the American J.J. Burns showed that the reason some mammals were susceptible to scurvy was the inability of their liver to produce the active enzyme L-gulonolactone oxidase, which is the last of the chain of four enzymes which synthesize vitamin C.[39][40] American biochemist Irwin Stone was the first to exploit vitamin C for its food preservative properties. He later developed the theory that humans possess a mutated form of the L-gulonolactone oxidase coding gene.

Daily requirements

The North American Dietary Reference Intake recommends 90 milligrams per day and no more than 2 grams per day (2000 milligrams per day).[41] Other related species sharing the same inability to produce vitamin C and requiring exogenous vitamin C consume 20 to 80 times this reference intake.[42][43] There is continuing debate within the scientific community over the best dose schedule (the amount and frequency of intake) of vitamin C for maintaining optimal health in humans.[44] It is generally agreed that a balanced diet without supplementation contains enough vitamin C to prevent scurvy in an average healthy adult, while those who are pregnant, smoke tobacco, or are under stress require slightly more.[41]

High doses (thousands of milligrams) may result in diarrhea in healthy adults. Proponents of alternative medicine (specifically orthomolecular medicine)[45] claim the onset of diarrhea to be an indication of where the body’s true vitamin C requirement lies, though this has yet to be clinically verified.

| United States vitamin C recommendations[41] | |

|---|---|

| Recommended Dietary Allowance (adult male) | 90 mg per day |

| Recommended Dietary Allowance (adult female) | 75 mg per day |

| Tolerable Upper Intake Level (adult male) | 2,000 mg per day |

| Tolerable Upper Intake Level (adult female) | 2,000 mg per day |

Government recommended intakes

Recommendations for vitamin C intake have been set by various national agencies:

- 40 milligrams per day: the United Kingdom's Food Standards Agency[2]

- 45 milligrams per day: the World Health Organization[46]

- 60 mg/day: Health Canada 2007 [1]

- 60–95 milligrams per day: United States' National Academy of Sciences[41]

The United States defined Tolerable Upper Intake Level for a 25-year-old male is 2,000 milligrams per day.

Alternative recommendations on intakes

Some independent researchers have calculated the amount needed for an adult human to achieve similar blood serum levels as vitamin C synthesising mammals as follows:

- 400 milligrams per day: the Linus Pauling Institute.[47]

- 500 milligrams per 12 hours: Professor Roc Ordman, from research into biological free radicals.[48]

- 3,000 milligrams per day (or up to 30,000 mg during illness): the Vitamin C Foundation.[49]

- 6,000–12,000 milligrams per day: Thomas E. Levy, Colorado Integrative Medical Centre.[50]

- 6,000–18,000 milligrams per day: Linus Pauling's personal use.[51]

Vitamin C high dose arguments

There is a strong advocacy movement for large doses of vitamin C based on in vitro and retrospective studies,[52] although large, randomized clinical trials on the effects of high doses on the general population have never taken place.

Many pro-vitamin C organizations promote usage levels well beyond the current Dietary Reference Intake (DRI). The movement is led by scientists and doctors such as Robert Cathcart, Ewan Cameron, Steve Hickey, Irwin Stone, Dr. Matthias Rath and twice Nobel Prize laureate, the late Linus Pauling. Pauling's 1986 book, How to Live Longer and Feel Better, was a bestseller that advocated taking many grams per day orally.

The biological halflife for vitamin C is fairly short, about 30 minutes in blood plasma, a fact which high dose advocates say mainstream researchers have failed to take into account. The Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences decided upon the current DRI based upon tests conducted 12 hours (24 half lives) after consumption.[44]

Vitamin C fights off the effects of having high cholesterol. Cholesterol repairs micro-fractures of blood vessel walls, but the sticky nature of cholesterol when filling in these micro-fractures promotes the buildup of more cholesterol at these areas of blood vessel walls. With the supplementation of Vitamin C in higher dosages the micro-fractures of blood vessels are repaired by the vitamin C and thus the buildup of cholesterol and subsequent blockages of blood vessels will not occur. (Dr. Craig Mencl researcher)[53]

Genetic rationales for high doses

Four gene products are necessary to manufacture vitamin C from glucose. The loss of activity of the gene for the last step, Pseudogene ΨGULO (GLO) the terminal enzyme responsible for manufacture of vitamin C, has occurred separately in the history of several species. The loss of this enzyme activity is responsible of inability of guinea pigs to synthesize vitamin C enzymatically, but this event happened independently of the loss in the haplorrhini suborder of primates, including humans. The remains of this non-functional gene with many mutations are, however, still present in the genome of the guinea pigs and in primates, including humans.[54][55] GLO activity has also been lost in all major families of bats, regardless of diet.[56] In addition, the function of GLO appears to have been lost several times, and possibly re-acquired, in several lines of passerine birds, where ability to make vitamin C varies from species to species. [57]

Loss of GLO activity in the primate order supposedly occurred about 63 million years ago, at about the time it split into the suborders haplorrhini (which lost the enzyme activity) and the more primitive strepsirrhini (which retained it). The haplorrhini ("simple nosed") primates, which cannot make vitamin C enzymatically, include the tarsiers and the simians (apes, monkeys and humans). The suborder strepsirrhini (bent or wet-nosed prosimians), which are still able to make vitamin C enzymatically, include lorises, galagos, pottos, and to some extent, lemurs. [58]

Stone[59] and Pauling[43] calculated, based on the diet of our primate cousins[42] (similar to what our common ancestors are likely to have consumed when the gene mutated), that the optimum daily requirement of vitamin C is around 2,300 milligrams for a human requiring 2,500 kcal a day.

The established RDA has been criticized by Pauling to be one that will prevent acute scurvy, and is not necessarily the dosage for optimal health.[51]

Therapeutic uses

Since its discovery vitamin C has been considered by some enthusiastic proponents a "universal panacea", although this led to suspicions by others of it being over-hyped.[60] Other proponents of high dose vitamin C consider that if it is given "in the right form, with the proper technique, in frequent enough doses, in high enough doses, along with certain additional agents and for a long enough period of time,"[61] it can prevent and, in many cases, cure, a wide range of common and/or lethal diseases, notably the common cold and heart disease,[62] although the NIH considers there to be "fair scientific evidence against this use."[63] Some proponents issued controversial statements involving it being a cure for AIDS,[64] bird flu, and SARS.[65][66][67]

Probably the most controversial issue, the putative role of ascorbate in the management of AIDS, is still unresolved, more than 16 years after a study published in the Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences (USA) showing that non toxic doses of ascorbate suppress HIV replication in vitro.[68] Other studies expanded on those results, but still, no large scale trials have yet been conducted.[69][70][71]

In an animal model of lead intoxication, vitamin C demonstrated "protective effects" on lead-induced nerve and muscle abnormalities[72] In smokers, blood lead levels declined by an average of 81% when supplemented with 1000 mg of vitamin C, while 200 mg were ineffective, suggesting that vitamin C supplements may be an "economical and convenient" approach to reduce lead levels in the blood.[73] The Journal of the American Medical Association published a study which concluded, based on an analysis of blood lead levels in the subjects of the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, that the independent, inverse relationship between lead levels and vitamin C in the blood, if causal, would "have public health implications for control of lead toxicity".[74]

Vitamin C has limited popularity as a treatment for autism spectrum symptoms. A 1993 study of 18 children with ASD found some symptoms reduced after treatment with vitamin C,[75] but these results have not been replicated.[76] Small clinical trials have found that vitamin C might improve the sperm count, sperm motility, and sperm morphology in infertile men[77], or improve immune function related to the prevention and treatment of age-associated diseases.[78] However, to date, no large clinical trials have verified these findings.

A preliminary study published in the Annals of Surgery found that the early administration of antioxidant supplementation using α-tocopherol and ascorbic acid reduces the incidence of organ failure and shortens ICU length of stay in this cohort of critically ill surgical patients.[79] More research on this topic is pending.

Dehydroascorbic acid, the main form of oxidized Vitamin C in the body, was shown to reduce neurological deficits and mortality following stroke, due to its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier, while "the antioxidant ascorbic acid (AA) or vitamin C does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier".[80] In this study published by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2001, the authors concluded that such "a pharmacological strategy to increase cerebral levels of ascorbate in stroke has tremendous potential to represent the timely translation of basic research into a relevant therapy for thromboembolic stroke in humans". No such "relevant therapies" are available yet and no clinical trials have been planned.

In January 2007 the US Food and Drug Administration approved a Phase I toxicity trial to determine the safe dosage of intravenous vitamin C as a possible cancer treatment for "patients who have exhausted all other conventional treatment options."[81] Additional studies over several years would be needed to demonstrate whether it is effective.[82]

In February 2007, an uncontrolled study of 39 terminal cancer patients showed that, on subjective questionnaires, patients reported an improvement in health, cancer symptoms, and daily function after administration of high-dose intravenous vitamin C.[83] The authors concluded that "Although there is still controversy regarding anticancer effects of vitamin C, the use of vitamin C is considered a safe and effective therapy to improve the quality of life of terminal cancer patients".

Vitamin C has been shown to lower intraocular pressure (IOP) in glaucoma patients when taken in massive amounts according to the September 2007 issue of GLEAMS.

In an August, 2008 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Mark Levine and colleagues at the National Institute of hooter and Digestive and Kidney Diseases found that direct injection of high doses of vitamin D reduced tumor weight and growth rate by about 50 percent in mouse models of ovarian, brain, and pancreatic cancers. No human therapies have yet been developed using this technique.[84]

A Cochrane Review in 2008 found no evidence to support any increase in lifespan as a result of vitamin C supplementation. As opposed to supplementation with vitamin A, vitamin E, and beta-carotene, vitamin C was not linked with a decrease in lifespan. [85]

Testing for ascorbate levels in the body

Simple tests use DCPIP to measure the levels of vitamin C in the urine and in serum or blood plasma. However these reflect recent dietary intake rather than the level of vitamin C in body stores.[6] Reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography is used for determining the storage levels of vitamin C within lymphocytes and tissue.

It has been observed that while serum or blood plasma levels follow the circadian rhythm or short term dietary changes, those within tissues themselves are more stable and give a better view of the availability of ascorbate within the organism. However, very few hospital laboratories are adequately equipped and trained to carry out such detailed analyses, and require samples to be analyzed in specialized laboratories.[86][87]

Adverse effects

Common side-effects

Relatively large doses of vitamin C may cause indigestion, particularly when taken on an empty stomach.

When taken in large doses, vitamin C causes diarrhea in healthy subjects. In one trial, doses up to 6 grams of ascorbic acid were given to 29 infants, 93 children of preschool and school age, and 20 adults for more than 1400 days. With the higher doses, toxic manifestations were observed in five adults and four infants. The signs and symptoms in adults were nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, flushing of the face, headache, fatigue and disturbed sleep. The main toxic reactions in the infants were skin rashes.[88]

Possible side-effects

As vitamin C enhances iron absorption[89], iron poisoning can become an issue to people with rare iron overload disorders, such as haemochromatosis. A genetic condition that results in inadequate levels of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) can cause sufferers to develop hemolytic anemia after ingesting specific oxidizing substances, such as very large dosages of vitamin C.[90]

There is a longstanding belief among the mainstream medical community that vitamin C causes kidney stones, which is based on little science.[91] Although recent studies have found a relationship[92] a clear relationship between excess ascorbic acid intake and kidney stone formation has not been generally established. [93]

In a study conducted on rats, during the first month of pregnancy, high doses of vitamin C may suppress the production of progesterone from the corpus luteum.[94] Progesterone, necessary for the maintenance of a pregnancy, is produced by the corpus luteum for the first few weeks, until the placenta is developed enough to produce its own source. By blocking this function of the corpus luteum, high doses of vitamin C (1000+ mg) are theorized to induce an early miscarriage.

In a group of spontaneously aborting women at the end of the first trimester, the mean values of vitamin C were significantly higher in the aborting group. However, the authors do state: 'This could not be interpreted as an evidence of causal association.'[95]

However, in a previous study of 79 women with threatened, previous spontaneous, or habitual abortion, Javert and Stander (1943) had 91% success with 33 patients who received vitamin C together with bioflavonoids and vitamin K (only three abortions), whereas all of the 46 patients who did not receive the vitamins aborted. [96]

Chance of overdose

As discussed previously, vitamin C exhibits remarkably low toxicity. The LD50 (the dose that will kill 50% of a population) in rats is generally accepted to be 11.9 grams per kilogram of body weight when taken orally.[35] The LD50 in humans remains unknown, owing to medical ethics that preclude experiments which would put patients at risk of harm. However, as with all substances tested in this way, the LD50 is taken as a guide to its toxicity in humans and no data to contradict this has been found.

Natural and artificial dietary sources

The richest natural sources are fruits and vegetables, and of those, the Kakadu plum and the camu camu fruit contain the highest concentration of the vitamin. It is also present in some cuts of meat, especially liver. Vitamin C is the most widely taken nutritional supplement and is available in a variety of forms, including tablets, drink mixes, crystals in capsules or naked crystals.

Vitamin C is absorbed by the intestines using a sodium-ion dependent channel. It is transported through the intestine via both glucose-sensitive and glucose-insensitive mechanisms. The presence of large quantities of sugar either in the intestines or in the blood can slow absorption.[97]

Plant sources

While plants are generally a good source of vitamin C, the amount in foods of plant origin depends on: the precise variety of the plant, the soil condition, the climate in which it grew, the length of time since it was picked, the storage conditions, and the method of preparation.[98]

The following table is approximate and shows the relative abundance in different raw plant sources.[99][100][101] As some plants were analyzed fresh while others were dried (thus, artifactually increasing concentration of individual constituents like vitamin C), the data are subject to potential variation and difficulties for comparison. The amount is given in milligrams per 100 grams of fruit or vegetable and is a rounded average from multiple authoritative sources:

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Kakadu plum | 3100 |

| Camu Camu | 2800 |

| Rose hip | 2000 |

| Acerola | 1600 |

| Seabuckthorn | 695 |

| Jujube | 500 |

| Indian gooseberry | 445 |

| Baobab | 400 |

| Blackcurrant | 200 |

| Red pepper | 190 |

| Parsley | 130 |

| Guava | 100 |

| Kiwifruit | 90 |

| Broccoli | 90 |

| Loganberry | 80 |

| Redcurrant | 80 |

| Brussels sprouts | 80 |

| Wolfberry (Goji) | 73 † |

| Lychee | 70 |

| Cloudberry | 60 |

| Elderberry | 60 |

| Persimmon | 60 |

† average of 3 sources; dried

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Papaya | 60 |

| Strawberry | 60 |

| Orange | 50 |

| Lemon | 40 |

| Melon, cantaloupe | 40 |

| Cauliflower | 40 |

| Garlic | 31 |

| Grapefruit | 30 |

| Raspberry | 30 |

| Tangerine | 30 |

| Mandarin orange | 30 |

| Passion fruit | 30 |

| Spinach | 30 |

| Cabbage raw green | 30 |

| Lime | 30 |

| Mango | 28 |

| Blackberry | 21 |

| Potato | 20 |

| Melon, honeydew | 20 |

| Cranberry | 13 |

| Tomato | 10 |

| Blueberry | 10 |

| Pineapple | 10 |

| Plant source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Pawpaw | 10 |

| Grape | 10 |

| Apricot | 10 |

| Plum | 10 |

| Watermelon | 10 |

| Banana | 9 |

| Carrot | 9 |

| Avocado | 8 |

| Crabapple | 8 |

| Cherry | 7 |

| Peach | 7 |

| Apple | 666 |

| Beetroot | 5 |

| Chokecherry | 5 |

| Pear | 4 |

| Lettuce | FUCK UR MOTHERS OLD STICKY RINKLY ASSSSSS! |

| Cucumber | 3 |

| Eggplant | 2 |

| Raisin | 2 |

| Fig | 2 |

| Bilberry | 1 |

| Horned melon | 0.5 |

| Medlar | 0.3 |

Animal sources

The overwhelming majority of species of animals and plants synthesise their own vitamin C, making some, but not all, animal products, sources of dietary vitamin C.

Vitamin C is most present in the liver and least present in the muscle. Since muscle provides the majority of meat consumed in the western human diet, animal products are not a reliable source of the vitamin. Vitamin C is present in mother's milk and, in lower amounts, in raw cow's milk, with pasteurized milk containing only trace amounts.[102] All excess vitamin C is disposed of through the urinary system.

The following table shows the relative abundance of vitamin C in various foods of animal origin, given in milligram of vitamin C per 100 grams of food:

| Animal Source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Calf liver (raw) | 36 |

| Beef liver (raw) | 31 |

| Oysters (raw) | 30 |

| Cod roe (fried) | 26 |

| Pork liver (raw) | 23 |

| Lamb brain (boiled) | 17 |

| Chicken liver (fried) | 13 |

| Animal Source | Amount (mg / 100g) |

|---|---|

| Lamb liver (fried) | 12 |

| Lamb heart (roast) | 11 |

| Lamb tongue (stewed) | 6 |

| Human milk (fresh) | 4 |

| Goat milk (fresh) | 2 |

| Cow milk (fresh) | 2 |

Food preparation

Vitamin C chemically decomposes under certain conditions, many of which may occur during the cooking of food. Normally, boiling water at 100°C is not hot enough to cause any significant destruction of the nutrient, which only decomposes at 190°C, [35] despite popular opinion. However, pressure cooking, roasting, frying and grilling food is more likely to reach the decomposition temperature of vitamin C. Longer cooking times also add to this effect, as will copper food vessels, which catalyse the decomposition.[35]

Another cause of vitamin C being lost from food is leaching, where the water-soluble vitamin dissolves into the cooking water, which is later poured away and not consumed. However, vitamin C doesn't leach in all vegetables at the same rate; research shows broccoli seems to retain more than any other.[103] Research has also shown that fresh-cut fruits don't lose significant nutrients when stored in the refrigerator for a few days.[104]

Vitamin C supplements

Vitamin C is the most widely taken dietary supplement.[105] It is available in many forms including caplets, tablets, capsules, drink mix packets, in multi-vitamin formulations, in multiple antioxidant formulations, and crystalline powder. Timed release versions are available, as are formulations containing bioflavonoids such as quercetin, hesperidin and rutin. Tablet and capsule sizes range from 25 mg to 1500 mg. Vitamin C (as ascorbic acid) crystals are typically available in bottles containing 300 g to 1 kg of powder (a teaspoon of vitamin C crystals equals 5,000 mg).

Artificial modes of synthesis

Vitamin C is produced from glucose by two main routes. The Reichstein process, developed in the 1930s, uses a single pre-fermentation followed by a purely chemical route. The modern two-step fermentation process, originally developed in China in the 1960s, uses additional fermentation to replace part of the later chemical stages. Both processes yield approximately 60% vitamin C from the glucose feed.[106]

Research is underway at the Scottish Crop Research Institute in the interest of creating a strain of yeast that can synthesise vitamin C in a single fermentation step from galactose, a technology expected to reduce manufacturing costs considerably.[30]

World production of synthesised vitamin C is currently estimated at approximately 110,000 tonnes annually. Main producers have been BASF/Takeda, DSM, Merck and the China Pharmaceutical Group Ltd. of the People's Republic of China. China is slowly becoming the major world supplier as its prices undercut those of the US and European manufacturers.[107] By 2008 only the DSM plant in Scotland remained operational outside the strong price competition from China. [108] The world price of vitamin C rose sharply in 2008 partly as a result of rises in basic food prices but also in anticipation of a stoppage of the two Chinese plants, situated at Shijiazhuang near Beijing, as part of a general shutdown of polluting industry in China over the period of the Olympic games.[109]

See also

References

- ^ McCluskey, Elwood S. (1985). "Which Vertebrates Make Vitamin C?" (PDF). Origins. 12 (2): 96–100.

- ^ a b "Vitamin C". Food Standards Agency (UK). Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ "Vitamin C". University of Maryland Medical Center. 2007. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Higdon, Jane, Ph.D. (2006-01-31). "Vitamin C". Oregon State University, Micronutrient Information Center. Retrieved 2007-03-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Padayatty S, Katz A, Wang Y, Eck P, Kwon O, Lee J, Chen S, Corpe C, Dutta A, Dutta S, Levine M (2003). "Vitamin C as an Anal Cavity: evaluation of its role in disease prevention" (PDF). J Am Coll Nutr. 22 (1): 18–35. PMID 12569111.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Vitamin C – Risk Assessment" (PDF). UK Food Standards Agency. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ Bjelakovic G; et al. (2007). "Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: systematic review and meta-analysis". JAMA. 297 (8): 842–57. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.842. PMID 17327526.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Meister A (1994). "Glutathione-ascorbic acid antioxidant system in animals" (PDF). J Biol Chem. 269 (13): 9397–400. PMID 8144521.

- ^ Levine M, Rumsey SC, Wang Y, Park JB, Daruwala R (2000). "Vitamin C". In Stipanuk MH (ed.). Biochemical and physiological aspects of human nutrition. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders. pp. 541–67. ISBN 0-7216-4452-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Prockop DJ, Kivirikko KI (1995). "Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy". Annu Rev Biochem. 64: 403–34. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. PMID 7574488.

- ^ Peterkofsky B (1991). "Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy". Am J Clin Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1135S – 1140S. PMID 1720597.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kivirikko KI, Myllylä R (1985). "Post-translational processing of procollagens". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 460: 187–201. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1985.tb51167.x. PMID 3008623.

- ^ a b MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: Ascorbic acid

- ^ Rebouche CJ (1991). "Ascorbic acid and carnitine biosynthesis" (PDF). Am J Clin Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1147S – 1152S. PMID 1962562.

- ^ Dunn WA, Rettura G, Seifter E, Englard S (1984). "Carnitine biosynthesis from gamma-butyrobetaine and from exogenous protein-bound 6-N-trimethyl-L-lysine by the perfused guinea pig liver. Effect of ascorbate deficiency on the in situ activity of gamma-butyrobetaine hydroxylase" (PDF). J Biol Chem. 259 (17): 10764–70. PMID 6432788.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levine M, Dhariwal KR, Washko P; et al. (1992). "Ascorbic acid and reaction kinetics in situ: a new approach to vitamin requirements". J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. Spec No: 169–72. PMID 1297733.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaufman S (1974). "Dopamine-beta-hydroxylase". J Psychiatr Res. 11: 303–16. doi:10.1016/0022-3956(74)90112-5. PMID 4461800.

- ^ Eipper BA, Milgram SL, Husten EJ, Yun HY, Mains RE (1993). "Peptidylglycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase: a multifunctional protein with catalytic, processing, and routing domains". Protein Sci. 2 (4): 489–97. PMC 2142366. PMID 8518727.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Eipper BA, Stoffers DA, Mains RE (1992). "The biosynthesis of neuropeptides: peptide alpha-amidation". Annu Rev Neurosci. 15: 57–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.ne.15.030192.000421. PMID 1575450.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Englard S, Seifter S (1986). "The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid". Annu. Rev. Nutr. 6: 365–406. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002053. PMID 3015170.

- ^ Lindblad B, Lindstedt G, Lindstedt S (1970). "The mechanism of enzymic formation of homogentisate from p-hydroxyphenylpyruvate". J Am Chem Soc. 92 (25): 7446–9. doi:10.1021/ja00728a032. PMID 5487549.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hediger MA (2002). "New view at C". Nat. Med. 8 (5): 445–6. doi:10.1038/nm0502-445. PMID 11984580.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Bánhegyi G, Mándl J (2001). "The hepatic glycogenoreticular system". Pathol Oncol Res. 7 (2): 107–10. PMID 11458272.

- ^ Harris, J. Robin (1996). Ascorbic Acid: Subcellular Biochemistry. Springer. p. 35. ISBN 0306451484. OCLC 34307319 46753025.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ "How Humans Make Up For An 'Inborn' Vitamin C Deficiency".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Milton K (1999). "Nutritional characteristics of wild primate foods: do the diets of our closest living relatives have lessons for us?". Nutrition. 15 (6): 488–98. doi:10.1016/S0899-9007(99)00078-7. PMID 10378206.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Proctor P (1970). "Similar functions of uric acid and ascorbate in man?". Nature. 228 (5274): 868. doi:10.1038/228868a0. PMID 5477017.

- ^ Stone, Irwin (July 16, 1978). "Eight Decades of Scurvy. The Case History of a Misleading Dietary Hypothesis". Retrieved 2007-04-06.

Biochemical research in the 1950's showed that the lesion in scurvy is the absence of the enzyme, L-Gulonolactone oxidase (GLO) in the human liver (Burns, 1959). This enzyme is the last enzyme in a series of four which converts blood sugar, glucose, into ascorbate in the mammalian liver. This liver metabolite, ascorbate, is produced in an unstressed goat for instance, at the rate of about 13,000 mg per day per 150 pounds body weight (Chatterjee, 1973). A mammalian feedback mechanism increases this daily ascorbate production many fold under stress (Subramanian et al., 1973)

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ C. Long; et al. (2003). "Ascorbic acid dynamics in the seriously ill and injured". Journal of Surgical Research. 109 (2): 144–148. doi:10.1016/S0022-4804(02)00083-5.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ a b R.D. cocksryummy & R. Viola. "Ascorbic acid biosynthesis in higher plants and micro-organisms" (PDF). Scottish Crop Research Institute. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Hancock RD, Galpin JR, Viola R. "Biosynthesis of L-ascorbic acid (vitamin C) by Saccharomyces cerevisiae" (PDF). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 186 (2): 245–50. PMID 10802179. Retrieved 2007-02-19.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The influence of smoking on vitamin C status in adults". BBC news and Cambridge University. 2000-09-31. Retrieved 2007-12-12.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Jacques Cartier's Second Voyage - 1535 - Winter & Scurvy". Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ Martini E. (2002). "Jacques Cartier witnesses a treatment for scurvy". Vesalius. PMID 12422875.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d "Safety (MSDS) data for ascorbic acid". Oxford University. 2005-10-09. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Cook, James (1999). The Journals of Captain Cook. Penguin Books. p. 38. ISBN 0140436472. OCLC 42445907.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kuhnlein HV, Receveur O, Soueida R, Egeland GM (2004). "Arctic indigenous peoples experience the nutrition transition with changing dietary patterns and obesity". J Nutr. 134 (6): 1447–53. PMID 15173410.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Pitt History - 1932: Charles Glen King". University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

In recognition of this medical breakthrough, some scientists believe that King deserved a Nobel Prize.

- ^ BURNS JJ, EVANS C (1956). "The synthesis of L-ascorbic acid in the rat from D-glucuronolactone and L-gulonolactone". J Biol Chem. 223 (2): 897–905. PMID 13385237.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Burns JJ, Moltz A, Peyser P (1956). "Missing step in guinea pigs required for the biosynthesis of L-ascorbic acid". Science. 124 (3232): 1148–9. doi:10.1126/science.124.3232.1148-a. PMID 13380431.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "US Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA)" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-02-19.

- ^ a b Milton K (2003). "Micronutrient intakes of wild primates: are humans different?" (PDF). Comp Biochem Physiol a Mol Integr Physiol. 136 (1): 47–59. doi:10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00084-9. PMID 14527629.

- ^ a b Pauling, Linus (1970). "Evolution and the need for ascorbic acid". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a. 67 (4): 1643–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.67.4.1643. PMC 283405. PMID 5275366. Cite error: The named reference "paulingevolution" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "Linus Pauling Vindicated; Researchers Claim RDA For Vitamin C is Flawed". PR Newswire. 6 July 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Cathcart, Robert (1994). "Vitamin C, Titrating To Bowel Tolerance, Fucking Canucks i wish they would win one fucking stanly cup we are one of the last teams to not have one.[[Anascorbemia]], and Acute Induced Scurvy". Orthomed. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

{{cite web}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - ^ "Vitamin and mineral requirements in human nutrition, 2nd edition" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2004. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ^ Higdon, Jane. "Linus Pauling Institute Recommendations". Oregon State University. Retrieved 2007-04-11.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ Roc Ordman. "The Scientific Basis Of The Vitamin C Dosage Of Nutrition Investigator". Beloit College. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ "Vitamin C Foundation's RDA". Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ Levy, Thomas E. (2002). Vitamin C Infectious Diseases, & Toxins. Xlibris. ISBN 1401069630. OCLC 123353969.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) Chapter 5 - Vitamin C optidosing. - ^ a b Pauling, Linus (1986). How to Live Longer and Feel Better. W. H. Freeman and Company. ISBN 0-380-70289-4. OCLC 154663991 15690499.

{{cite book}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Douglas RM, Hemilä H (2005). "Vitamin C for Preventing and Treating the Common Cold". PLoS Medicine. 2 (6): e168. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020168.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ivanov V, Ivanova S, Roomi MW, Kalinovsky T, Niedzwiecki A, Rath M (2007). "Extracellular matrix-mediated control of aortic smooth muscle cell growth and migration by a combination of ascorbic acid, lysine, proline, and catechins". J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 50 (5): 541–7. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e318145148e. PMID 18030064.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Nutrient Synergy – A Mixture of Ascorbic Acid, Lysine, Proline, Arginine, Cysteine and Green Tea Extract Suppresses Autocrine Inflammatory Response in Cultured Human Aortic Smooth Muscle Cells - ^ Nishikimi M, Kawai T, Yagi K (1992). "Guinea pigs possess a highly mutated gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the key enzyme for L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis missing in this species". J Biol Chem. 267 (30): 21967–72. PMID 1400507.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ohta Y, Nishikimi M (1999). WORLD OF WARCRAFT KICKS ASS! .com/retrieve/pii/S0304-4165(99)00123-3 "Random nucleotide substitutions in primate nonfunctional gene for L-gulono-gamma-lactone oxidase, the missing enzyme in L-ascorbic acid biosynthesis". Biochim Biophys Acta. 1472 (1–2): 408–11. PMID 10572964.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ A trace of GLO was detected in only 1 of 34 bat species tested, across the range of 6 families of bats tested: See Jenness R, Birney E, Ayaz K (1980). "Variation of L-gulonolactone oxidase activity in placental mammals". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology. 67B: 195–204.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Earlier reports of only fruit bats being deficient were based on smaller samples. - ^ Carlos Martinez del Rio (1997). "Can passerines synthesize vitamin C?". The Auk.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pollock JI, Mullin RJ (1987). "Vitamin C biosynthesis in prosimians: evidence for the anthropoid affinity of Tarsius". Am J Phys Anthropol. 73 (1): 65–70. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330730106. PMID 3113259.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stone, Irwin (1972). The Healing Factor: Vitamin C Against Disease. Grosset and Dunlap. ISBN 0-448-11693-6. OCLC 3967737.

- ^ Hemilä, Harri (2006). "Do vitamins C and E affect respiratory infections?" (PDF). University of Helsinki. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Levy, Thomas E. (2002). Curing the Incurable: Vitamin C, Infectious Diseases, and Toxins. Livon Books. p. 36. ISBN 1-4010-6963-0. OCLC 123353969.

- ^ Rath MW, Pauling LC. U.S. patent 5,278,189 Prevention and treatment of occlusive cardiovascular disease with ascorbate and substances that inhibit the binding of lipoprotein(a). USPTO. 11 Jan 1994.

- ^ "Vitamin C (Ascorbic acid)". MedLine Plus. National Institute of Health. 2006-08-01. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Nigeria: Vitamin C Can Suppress HIV/Aids Virus". allAfrica.com. 2006-05-22. Retrieved 2006-06-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Hemilä H (2003). "Vitamin C and SARS coronavirus". J Antimicrob Chemother. 52 (6): 1049–50. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh002. PMID 14613951.

- ^ Boseley, Sarah (2005-05-14). "Discredited doctor's 'cure' for Aids ignites life-and-death struggle in South Africa". The Guardian. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Rath, Matthias (2005). "Open letter from Dr. Matthias Rath MD to German Chancellor Merkel". Dr. Rath Health Foundation. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ^ Harakeh S, Jariwalla R, Pauling L (1990). "Suppression of human immunodeficiency virus replication by ascorbate in chronically and acutely infected cells". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S a. 87 (18): 7245–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.18.7245. PMID 1698293.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Harakeh S, Jariwalla R (1991). "Comparative study of the anti-HIV activities of ascorbate and thiol-containing reducing agents in chronically HIV-infected cells". Am J Clin Nutr. 54 (6 Suppl): 1231S – 1235S. PMID 1720598.

- ^ Harakeh S, Jariwalla R (1997). "NF-kappa B-independent suppression of HIV expression by ascorbic acid". AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 13 (3): 235–9. PMID 9115810.

- ^ Harakeh S, Jariwalla R. "Ascorbate effect on cytokine stimulation of HIV production". Nutrition. 11 (5 Suppl): 684–7. PMID 8748252.

- ^ Hasan MY, Alshuaib WB, Singh S, Fahim MA (2003). "Effects of ascorbic acid on lead induced alterations of synaptic transmission and contractile features in murine dorsiflexor muscle". Life Sci. 73 (8): 1017–25. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(03)00374-6. PMID 12818354.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Dawson E, Evans D, Harris W, Teter M, McGanity W (1999). "The effect of ascorbic acid supplementation on the blood lead levels of smokers". J Am Coll Nutr. 18 (2): 166–70. PMID 10204833.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Simon JA, Hudes ES (1999). "Relationship of ascorbic acid to blood lead levels". JAMA. 281 (24): 2289–93. doi:10.1001/jama.281.24.2289. PMID 10386552.

- ^ Dolske MC, Spollen J, McKay S, Lancashire E, Tolbert L (1993). "A preliminary trial of ascorbic acid as supplemental therapy for autism". Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 17 (5): 765–74. doi:10.1016/0278-5846(93)90058-Z. PMID 8255984.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Levy SE, Hyman SL (2005). "Novel treatments for autistic spectrum disorders". Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 11 (2): 131–42. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20062. PMID 15977319.

- ^ Akmal M, Qadri J, Al-Waili N, Thangal S, Haq A, Saloom K (2006). "Improvement in human semen quality after oral supplementation of vitamin C". J Med Food. 9 (3): 440–2. doi:10.1089/jmf.2006.9.440. PMID 17004914.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ de la Fuente M, Ferrández M, Burgos M, Soler A, Prieto A, Miquel J (1998). "Immune function in aged women is improved by ingestion of vitamins C and E". Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 76 (4): 373–80. doi:10.1139/cjpp-76-4-373. PMID 9795745.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nathens A, Neff M, Jurkovich G, Klotz P, Farver K, Ruzinski J, Radella F, Garcia I, Maier R (2002). "Randomized, prospective trial of antioxidant supplementation in critically ill surgical patients". Ann Surg. 236 (6): 814–22. doi:10.1097/00000658-200212000-00014. PMC 1422648. PMID 12454520.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

Huang J, Agus DB, Winfree CJ, Kiss S, Mack WJ, McTaggart RA, Choudhri TF, Kim LJ, Mocco J, Pinsky DJ, Fox WD, Israel RJ, Boyd TA, Golde DW, Connolly ES Jr. (2001). "Dehydroascorbic acid, a blood-brain barrier transportable form of vitamin C, mediates potent cerebroprotection in experimental stroke". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (20): 11720–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.171325998. PMID 11573006.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "FDA OKs vitamin C trial for cancer". Physorg.com. January 12, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

Federal approval of a clinical trial on intravenous vitamin C as a cancer treatment lends credence to alternative cancer care, U.S. researchers said.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Study of High-Dose Intravenous (IV) Vitamin C Treatment in Patients With Solid Tumors". Retrieved 2007-08-02.