Yellow River: Difference between revisions

Katieh5584 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 204.10.220.125 (talk) to last revision by Vieque (HG) |

Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 90: | Line 90: | ||

===Medieval times=== |

===Medieval times=== |

||

In 923 a desperate [[Later Liang (Five Dynasties)|Later Liang]] general [[Duan Ning]] again broke the dikes, flooding {{convert|1000|sqmi|sp=us}} in a failed attempt to protect the Later Liang capital from the [[Later Tang]]. A similar proposal from the [[Southern Song|Song]] engineer Li Chun concerning flooding the lower reaches of the river to protect the central plains from the [[Khitai]] was overruled in 1020: the [[Treaty of Shanyuan]] between the two states had expressly forbidden the Song from establishing new moats or changing river |

In 923 a desperate [[Later Liang (Five Dynasties)|Later Liang]] general [[Duan Ning]] again broke the dikes, flooding {{convert|1000|sqmi|sp=us}} in a failed attempt to protect the Later Liang capital from the [[Later Tang]]. A similar proposal from the [[Southern Song|Song]] engineer Li Chun concerning flooding the lower reaches of the river to protect the central plains from the [[Khitai]] was overruled in 1020: the [[Treaty of Shanyuan]] between the two states had expressly forbidden the Song from establishing new moats or changing river coursehdjdijaadsoksjskjdksccs.<ref name="Sedtime">Elvin, Mark & Liu Cuirong<!--sic--> (eds.) ''Studies in Environment and History:'' ''[http://books.google.com/books?id=tAxmcRXKpaUC&pg=PA554 Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History]'', pp. 554 ff. Cambridge Uni. Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-56381-X. Accessed 15 Oct. 2011.</ref> |

||

Breaches occurred regardless: one at [[Henglong]] in 1034 divided the course in three and repeatedly flooded the northern regions of [[Dezhou]] and [[Bozhou (Song)|Bozhou]].<ref name="Sedtime"/> The Song worked for five years futilely attempting to restore the previous course{{spaced ndash}}using over 35,000 employees, 100,000 conscripts, and 220,000 tons of wood and bamboo in a single year<ref name="Sedtime"/>{{spaced ndash}}before abandoning the project in 1041. The more sluggish river then occasioned a breach at [[Shanghu]] that sent the main outlet north towards [[Tianjin]] in 1048<ref name="Treg"/> and by 1194 blocked the mouth of the [[Huai River]].<ref name="R. Grousset">Grousset, Rene. ''The Rise and Splendour of the Chinese Empire'', p. 303. University of California Press, 1959.<!--Although note material error in |

Breaches occurred regardless: one at [[Henglong]] in 1034 divided the course in three and repeatedly flooded the northern regions of [[Dezhou]] and [[Bozhou (Song)|Bozhou]].<ref name="Sedtime"/> The Song worked for five years futilely attempting to restore the previous course{{spaced ndash}}using over 35,000 employees, 100,000 conscripts, and 220,000 tons of wood and bamboo in a single year<ref name="Sedtime"/>{{spaced ndash}}before abandoning the project in 1041. The more sluggish river then occasioned a breach at [[Shanghu]] that sent the main outlet north towards [[Tianjin]] in 1048<ref name="Treg"/> and by 1194 blocked the mouth of the [[Huai River]].<ref name="R. Grousset">Grousset, Rene. ''The Rise and Splendour of the Chinese Empire'', p. 303. University of California Press, 1959.<!--Although note material error in mjxxzmkzmlzmxzsource's claim the river remained on only this path until 1853--></ref> The build up of silt deposits was such that even after the Yellow River later shifted its course, the Huai was no longer able to flow along its historic one. Instead, its water pools into [[Hongze Lake]] and then runs southward toward the [[Yangtze River]].{{Citation needed|date=May 2009}} |

||

A flood in [[1344 Yellow River flood|1344]] returned the Yellow River south of Shandong. The Yuan dynasty was waning, and the emperor forced enormous teams to build new embankments for the river. The terrible conditions helped fuel rebellions that led to the founding of the Ming dynasty.<ref name="Gascoigne"/> The course changed again in [[1391 Yellow River flood|1391]] when the river flooded from Kaifeng to Fengyang in Anhui. It was finally stabilized by the eunuch [[Li Xing]] during the public works projects following the [[1494 Yellow River flood|1494 flood]].<ref name="eunuch"/> |

A flood in [[1344 Yellow River flood|1344]] returned the Yellow River south of Shandong. The Yuan dynasty was waning, and the emperor forced enormous teams to build new embankments for the river. The terrible conditions helped fuel rebellions that led to the founding of the Ming dynasty.<ref name="Gascoigne"/> The course changed again in [[1391 Yellow River flood|1391]] when the river flooded from Kaifeng to Fengyang in Anhui. It was finally stabilized by the eunuch [[Li Xing]] during the public works projects following the [[1494 Yellow River flood|1494 flood]].<ref name="eunuch"/> |

||

The river flooded many times in the 16th century, including in 1526, 1534, 1558, and 1587. Each flood affected the river's lower course.<ref name="eunuch">Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry.<!--sic--> ''SUNY Series in Chinese Local Studies'': ''[http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Ka6jNJcX_ygC&pg=PA200 The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty]''. SUNY Press, 1996. ISBN |

The river flooded many times in the 16th century, including in 1526, 1534, 1558, and 1587. Each flood affected the river's lower course.<ref name="eunuch">Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry.<!--sic--> ''SUNY Series in Chinese Local Studies'': ''[http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Ka6jNJcX_ygC&pg=PA200 The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty]''. SUNY Press, 1996. ISBN 07914268ndfndfjspdec74, 9780791426876. Accessed 16 Oct 2012.</ref> |

||

The [[1642 Yellow River flood|1642 flood]] was man-made, caused by the attempt of the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] governor of [[Kaifeng]] to use the river to destroy the peasant rebels under [[Li Zicheng]] who had been besieging the city for the past six months.<ref>Lorge, Peter Allan. ''[http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SE2Gw8rjuXQC&pg=PA147 War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795]'', p. 147. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-31691-0.</ref> He directed his men to break the dikes in an attempt to flood the rebels, but destroyed his own city instead: the flood and the ensuing famine and plague are estimated to have killed 300,000 of the |

The [[1642 Yellow River flood|1642 flood]] was man-made, caused by the attempt of the [[Ming Dynasty|Ming]] governor of [[Kaifeng]] to use the river to destroy the peasant rebels under [[Li Zicheng]] who had been besieging the city for the past six months.<ref>Lorge, Peter Allan. ''[http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SE2Gw8rjuXQC&pg=PA147 War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795]'', p. 147. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-31691-0.</ref> He directed his men to break the dikes in an attempt to flood the rebels, but destroyed his own city instead: the flood and the ensuing famine and plague are estimated to have killed 300,000 of the citfsjfsndfvfdvvfdscvy's previous population of 378,000.<ref>Xu Xin.<!--This order--> ''[http://books.google.com.hk/books?id=GAAWkYBNu5sC&pg=PA47 The Jews of Kaifeng, China: History, Culture, and Religion]'', p. 47. Ktav Publishing Inc, 2003. ISBN 978-0-88125-791-5.</ref> The once-prosperous city was nearly abandoned until its rebuilding under the [[Kangxi Emperor]] in the [[Qing Dynasty]]. |

||

===Recent times=== |

===Recent times=== |

||

Revision as of 12:27, 14 March 2014

| Yellow River | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The "Mother River" monument in Lanzhou | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃河 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄河 | ||||||||||

| Postal | Hwang Ho | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||

| Tibetan | རྨ་ཆུ། | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||

| Mongolian Cyrillic | [Хатан гол Ȟatan Gol Шар мөрөн Šar Mörön] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | ||||||||||

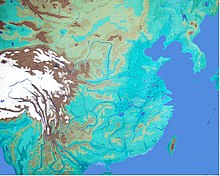

The Yellow River or Huang He is the second-longest river in Asia, following the Yangtze River, and the sixth-longest in the world at the estimated length of 5,464 km (3,395 mi).[1] Originating in the Bayan Har Mountains in Qinghai province of western China, it flows through nine provinces, and it empties into the Bohai Sea near the city of Dongying in Shandong province. The Yellow River basin has an east–west extent of about 1,900 kilometers (1,180 mi) and a north–south extent of about 1,100 km (680 mi). Its total basin area is about 742,443 square kilometers (286,659 sq mi).

The Yellow River is called "the cradle of Chinese civilization", because its basin was the birthplace of ancient Chinese civilization, and it was the most prosperous region in early Chinese history. However, frequent devastating floods and course changes produced by the continual elevation of the river bed, sometimes above the level of its surrounding farm fields, has also earned it the unenviable names China's Sorrow and Scourge of the Sons of Han.[2]

Name

Early Chinese literature including the Yu Gong or Tribute of Yu dating to the Warring States period (475 – 221 BC) refers to the Yellow River as simply 河 (Old Chinese: *C.gˤaj[3]), a character that has come to mean "river" in modern usage. The first appearance of the name 黃河 (Old Chinese: *N-kʷˤaŋ C.gˤaj; Middle Chinese: Hwang Ha[3]) is in the Book of Han written during the Western Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 9). The adjective "yellow" describes the perennial color of the muddy water in the lower course of the river, which arises from soil (loess) being carried downstream.

One of its older Mongolian names was the "Black River",[4] because the river runs clear before it enters the Loess Plateau, but the current name of the river among Inner Mongolians is Ȟatan Gol (Хатан гол, "Queen River").[5] In Mongolia itself, it is simply called the Šar Mörön (Шар мөрөн, "Yellow River").

In Qinghai, the river's Tibetan name is "River of the Peacock" (Tibetan: རྨ་ཆུ།, Ma Chu; Chinese: s 玛曲, t 瑪曲, p Mǎ Qū).

The name Hwang Ho in English is the Postal Map romanization of the river's Mandarin name.

History

Dynamics

The Yellow River is one of several rivers that are essential for China's very existence. At the same time, however, it has been responsible for several deadly floods, including the only natural disasters in recorded history that have killed more than a million people. The deadliest was a 1332-33 flood that killed 7 million people. Close behind is the 1887 flood, which killed anywhere from 900,000 to 2 million people, and a 1931 flood (part of a massive number of floods that year) that killed 1-4 million people.[6]

The cause of the floods is the large amount of fine-grained loess carried by the river from the Loess Plateau, which is continuously deposited along the bottom of its channel. The sedimentation causes natural dams to slowly accumulate. These subaqueous dams were unpredictable and generally undetectable. Eventually, the enormous amount of water has to find a new way to the sea, forcing it to take the path of least resistance. When this happens, it bursts out across the flat North China Plain, sometimes taking a new channel and inundating any farmland, cities or towns in its path. The traditional Chinese response of building higher and higher levees along the banks sometimes also contributed to the severity of the floods: When flood water did break through the levees, it could no longer drain back into the river bed as it would after a normal flood as the river bed was sometimes now higher than the surrounding countryside. These changes could cause the river's mouth to shift as much as 480 km (300 mi), sometimes reaching the ocean to the north of Shandong Peninsula and sometimes to the south.[7]

Another historical source of devastating floods is the collapse of upstream ice dams in Inner Mongolia with an accompanying sudden release of vast quantities of impounded water. There have been 11 such major floods in the past century, each causing tremendous loss of life and property. Nowadays, explosives dropped from aircraft are used to break the ice dams before they become dangerous.[8]

Prior to the advent of modern dams in China, the Yellow River was extremely prone to flooding. In the 2,540 years prior to A.D. 1946, the Yellow River has been reckoned to have flooded 1,593 times, shifting its course 26 times noticeably and nine times severely.[9] These floods include some of the deadliest natural disasters ever recorded. Before modern disaster management, when floods occurred, some of the population might initially die from drowning but then many more would suffer from the ensuing famine and spread of diseases.[10]

Ancient times

Historical documents from the Spring and Autumn period[11] and Qin Dynasty[12] indicate that the Yellow River at that time flowed considerably north of its present course. These accounts show that after the river passed Luoyang, it flowed along the border between Shanxi and Henan Provinces, then continued along the border between Hebei and Shandong before emptying into Bohai Bay near present-day Tianjin. Another outlet followed essentially the present course.[9]

The river left these paths in 602 BC[11] and shifted completely south of the Shandong Peninsula.[9] Sabotage of dikes, canals, and reservoirs and deliberate flooding of rival states became a standard military tactic during the Warring States period.[13] Major flooding in AD 11 is credited with the downfall of the short-lived Xin dynasty, and another flood in AD 70 returned the river north of Shandong on essentially its present course.[9]

Medieval times

In 923 a desperate Later Liang general Duan Ning again broke the dikes, flooding 1,000 square miles (2,600 km2) in a failed attempt to protect the Later Liang capital from the Later Tang. A similar proposal from the Song engineer Li Chun concerning flooding the lower reaches of the river to protect the central plains from the Khitai was overruled in 1020: the Treaty of Shanyuan between the two states had expressly forbidden the Song from establishing new moats or changing river coursehdjdijaadsoksjskjdksccs.[14]

Breaches occurred regardless: one at Henglong in 1034 divided the course in three and repeatedly flooded the northern regions of Dezhou and Bozhou.[14] The Song worked for five years futilely attempting to restore the previous course – using over 35,000 employees, 100,000 conscripts, and 220,000 tons of wood and bamboo in a single year[14] – before abandoning the project in 1041. The more sluggish river then occasioned a breach at Shanghu that sent the main outlet north towards Tianjin in 1048[9] and by 1194 blocked the mouth of the Huai River.[15] The build up of silt deposits was such that even after the Yellow River later shifted its course, the Huai was no longer able to flow along its historic one. Instead, its water pools into Hongze Lake and then runs southward toward the Yangtze River.[citation needed]

A flood in 1344 returned the Yellow River south of Shandong. The Yuan dynasty was waning, and the emperor forced enormous teams to build new embankments for the river. The terrible conditions helped fuel rebellions that led to the founding of the Ming dynasty.[7] The course changed again in 1391 when the river flooded from Kaifeng to Fengyang in Anhui. It was finally stabilized by the eunuch Li Xing during the public works projects following the 1494 flood.[16]

The river flooded many times in the 16th century, including in 1526, 1534, 1558, and 1587. Each flood affected the river's lower course.[16]

The 1642 flood was man-made, caused by the attempt of the Ming governor of Kaifeng to use the river to destroy the peasant rebels under Li Zicheng who had been besieging the city for the past six months.[17] He directed his men to break the dikes in an attempt to flood the rebels, but destroyed his own city instead: the flood and the ensuing famine and plague are estimated to have killed 300,000 of the citfsjfsndfvfdvvfdscvy's previous population of 378,000.[18] The once-prosperous city was nearly abandoned until its rebuilding under the Kangxi Emperor in the Qing Dynasty.

Recent times

Between 1851 and 1855,[9][15][16] it returned to the north amid the floods that provoked the Nien and Taiping Rebellions. The 1887 flood has been estimated to have killed between 900,000 and 2 million people,[19] and is the second-worst natural disaster in history (excluding famines and epidemics). The Yellow River more or less adopted its present course during the 1897 flood.[15][20]

The 1931 flood killed an estimated 1,000,000 to 4,000,000,[19] and is the worst natural disaster recorded (excluding famines and epidemics).

On 9 June 1938, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Nationalist troops under Chiang Kai-Shek broke the levees holding back the river near the village of Huayuankou in Henan, causing what has been called a "war-induced natural disaster".[by whom?] The goal of the operation was to stop the advancing Japanese troops by following a strategy of "using water as a substitute for soldiers" (yishui daibing). The 1938 flood of an area covering 54,000 km2 (20,800 sq mi) took some 500,000 to 900,000 Chinese lives, along with an unknown number of Japanese soldiers. The flood prevented the Japanese army from taking Zhengzhou, on the southern bank of the Yellow River, but did not stop them from reaching their goal of capturing Wuhan, which was the temporary seat of the Chinese government and straddles the Yangtze River.[21]

Geography

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

According to the China Exploration and Research Society, the source of the Yellow River is at 34° 29' 31.1" N, 96° 20' 24.6" E in the Bayan Har Mountains near the eastern edge of the Yushu Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture. The source tributuaries drain into Gyaring Lake and Ngoring Lake on the western edge of Golog Prefecture high in the Bayan Har Mountains of Qinghai. In the Zoige Basin along the boundary with Gansu, the Yellow River loops northwest and then northeast before turning south, creating the "Ordos Loop", and then flows generally eastward across the North China Plain to the Gulf of Bohai, draining a basin of 752,443 square kilometers (290,520 sq mi) which nourishes 140 million people with drinking water and irrigation.[22]

The Yellow River passes through seven present-day provinces and two autonomous regions, namely (from west to east) Qinghai, Gansu, Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, and Shandong. Major cities along the present course of the Yellow River include (from west to east) Lanzhou, Yinchuan, Wuhai, Baotou, Luoyang, Zhengzhou, Kaifeng, and Jinan. The current mouth of the Yellow River is located at Kenli County, Shandong.

The river is commonly divided into three stages. These are roughly the northeast of the Tibetan Plateau, the Ordos Loop and the North China Plain. However, different scholars have different opinions on how the three stages are divided.[citation needed] This article adopts the division used by the Yellow River Conservancy Commission.[23]

Upper reaches

The upper reaches of the Yellow River constitute a segment starting from its source in the Bayan Har Mountains and ending at Hekou Town (Togtoh County), Inner Mongolia just before it turns sharply to the south. This segment has a total length of 3,472 kilometers (2,157 mi) and total basin area of 386,000 square kilometers (149,000 sq mi), 51.4% of the total basin area. Along this length, the elevation of the Yellow River drops 3,496 meters (11,470 ft), with an average grade of 0.10%.

The source section flows mainly through pastures, swamps, and knolls between the Bayan Har Mountains, and the Anemaqen (Amne Machin) Mountains. The river water is clear and flows steadily. Crystal clear lakes are characteristic of this section. The two main lakes along this section are Lake Zhaling (扎陵湖) and Lake Eling (鄂陵湖), with capacities of 4.7 billion and 10.8 billion m³ (166 and 381 billion ft3), respectively. At elevations over 4,290 m (14,070 ft)) above sea level they are the two largest plateau freshwater lakes nationwide. A significant amount of land in the Yellow River's source area has been designated as the Sanjiangyuan ("'Three Rivers' Sources") National Nature Reserve, to protect the source region of the Yellow River, the Yangtze, and the Mekong.

The valley section stretches from Longyang Gorge in Qinghai to Qingtong Gorge in Gansu. Steep cliffs line both sides of the river. The water bed is narrow and the average drop is large, so the flow in this section is extremely turbulent and fast. There are 20 gorges in this section, the most famous of these being the Longyang, Jishi, Liujia, Bapan, and Qingtong gorges. The flow conditions in this section makes it the best location for hydroelectric plants.

After emerging from the Qingtong Gorge, the river comes into a section of vast alluvial plains, the Yinchuan Plain and Hetao Plain. In this section, the regions along the river are mostly deserts and grasslands, with very few tributaries. The flow is slow. The Hetao Plain has a length of 900 km (560 mi) and width of 30 to 50 km (19 to 31 mi). It is historically the most important irrigation plain along the Yellow River.

Middle reaches

The part of the Yellow River (see Ordos Loop) between Hekou Town (Togtoh County), in Inner Mongolia and Zhengzhou, Henan constitutes the middle reaches of the river. The middle reaches are 1,206 km (749 mi) long, with a basin area of 344,000 square kilometers (133,000 sq mi), 45.7% of the total, with a total elevation drop of 890 m (2,920 ft), an average drop of 0.074%. There are 30 large tributaries along the middle reaches, and the water flow is increased by 43.5% on this stage. The middle reaches contribute 92% of the river's silts.

The middle stream of the Yellow River passes through the Loess Plateau, where substantial erosion takes place. The large amount of mud and sand discharged into the river makes the Yellow River the most sediment-laden river in the world. The highest recorded annual level of silts discharged into the Yellow River is 3.91 billion tons in 1933. The highest silt concentration level was recorded in 1977 at 920 kg/m³ (57.4 lb/ft3). These sediments later deposit in the slower lower reaches of the river, elevating the river bed and creating the famous "river above ground".

From Hekou to Yumenkou, the river passes through the longest series of continuous valleys on its main course, collectively called the Jinshan Valley. The abundant hydrodynamic resources stored in this section make it the second most suitable area to build hydroelectric power plants. The famous Hukou Waterfall is in the lower part of this valley, on the border of Shanxi and Shaanxi.

Lower reaches

In the lower reaches, from Zhengzhou, Henan to its mouth, a distance of 786 km (488 mi), the river is confined to a levee-lined course as it flows to the northeast across the North China Plain before emptying into the Bohai Sea. The basin area in this stage is only 23,000 square kilometers (8,900 sq mi), a mere 3% of the total, because few tributaries add to the flow in this stage; nearly all rivers to the south drain into the Huai River, whereas those to the north drain into the Hai River. The total drop in elevation of the lower reaches is 93.6 m (307 ft), with an average grade of 0.012%.

The silts received from the middle reaches form sediments here, elevating the river bed. During 2,000 years of levee construction, excessive sediment deposits have raised the riverbed several meters above the surrounding ground.

At Kaifeng, Henan, the Yellow River is 10 meters (33 ft) above the ground level.[24]

Tributaries

Tributaries of the Yellow River include (upstream to downstream (?))

- White River (白河)

- Black River (黑河)

- Star River (湟水)

- Daxia River (大夏河)

- Tao River (洮河)

- Zuli River (祖厉河/祖厲河)

- Qingshui River (清水河)

- Dahei River (大黑河)

- Kuye River (窟野河)

- Wuding River (无定河/無定河)

- Fen River (汾河)

- Wei River (渭河)

- Luo River (洛河)

- Qin River (沁河)

- Dawen River (大汶河)

- Kuo River

The Wei River is the largest of these tributaries.

Characteristics

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

The Yellow River is notable for the large amount of silt it carries—1.6 billion tons annually at the point where it descends from the Loess Plateau. If it is running to the sea with sufficient volume, 1.4 billion tons are carried to the sea annually.[citation needed] One estimate gives 34 kilograms of silt per cubic meter as opposed to 10 for the Colorado and 1 for the Nile.[25]

Its average discharge is said to be 2,110 cubic meters per second (32,000 for the Yangtze), with a maximum of 25,000 and minimum of 245. However, since 1972, it often runs dry before it reaches the sea. The low volume is due to increased agricultural irrigation, increased by a factor of five since 1950. Water diverted from the river as of 1999 served 140 million people and irrigated 74,000 km² (48,572 mi²) of land.[22] The Yellow River delta totals 8,000 square kilometers (3,090 mi²). However, with the decrease in silt reaching the sea, it has been reported to be shrinking slightly each year since 1996 through erosion.[26]

The highest volume occurs during the rainy season from July to October, when 60% of the annual volume of the river flows. Maximum demand for irrigation is needed between March and June. In order to capture excess water for use when needed and for flood control and electricity generation, several dams have been built, but their expected life is limited due to the high silt load. A proposed South–North Water Transfer Project involves several schemes to divert water from the Yangtze River: one in the western headwaters of the rivers where they are closest to one another, another from the upper reaches of the Han River, and a third using the route of the old Grand Canal.[citation needed]

Due to its heavy load of silt the Yellow River is a depositing stream – that is, it deposits part of its carried burden of soil in its bed in stretches where it is flowing slowly. These deposits elevate the riverbed which flows between natural levees in its lower reaches. Should a flood occur, the river may break out of the levees into the surrounding lower flood plain and take a new channel. Historically this has occurred about once every hundred years. In modern times, considerable effort has been made to strengthen levees and control floods.[citation needed]

Hydroelectric power dams

Below is the list of hydroelectric power stations built on the Yellow River, arranged according to the first year of operation (in brackets):

- Sanmenxia Dam hydroelectric power station (1960; Sanmenxia, Henan)

- Sanshenggong hydroelectric power station (1966)

- Qingtong Gorge hydroelectric power station (1968; Qingtongxia, Ningxia)

- Liujiaxia Dam (Liujia Gorge) (1974; Yongjing County, Gansu)

- Lijiaxia Dam (1997) (Jainca County, Qinghai)

- Yanguoxia Dam (Yanguo Gorge) hydroelectric power station (1975; Yongjing County, Gansu)

- Tianqiao hydroelectric power station (1977)

- Bapanxia Dam (Bapan Gorge) (1980; Xigu District, Lanzhou, Gansu)

- Longyangxia Dam (1992; Gonghe County, Qinghai)

- Da Gorge hydroelectric power station (1998)

- Li Gorge hydroelectric power station (1999)

- Wanjiazhai Dam (1999; Pianguan County, Shaanxi and Inner Mongolia)

- Xiaolangdi Dam (2001) (Jiyuan, Henan)

- Laxiwa Dam (2010) (Guide County, Qinghai)

As reported in 2000, the 7 largest hydro power plants (Longyangxia, Lijiaxia, Liujiaxia, Yanguoxia, Bapanxia, Daxia and Qinglongxia) had the total installed capacity of 5,618 MW.[27]

Crossings

The main bridges and ferries by the province names in the order of downstream to upstream are:[28][29][30]

- Dongying Yellow River Bridge

- Shengli Yellow River Bridge (Dongying)

- Lijin Yellow River Bridge (Dongying)

- Binzhou Yellow River Road-Railway Bridge

- Binzhou Yellow River Highway Bridge

- Binzhou–Laiwu Expressway Binzhou Yellow River Bridge (Binzhou–Zibo)

- Huiqing Yellow River Bridge (Binzhou–Zibo)

- Jiyang Yellow River Bridge (Jinan)

- G20 Qingdao–Yinchuan Expressway Jinan Yellow River Bridge (Jinan)

- Jinan Yellow River Bridge

- Luokou Yellow River Railway Bridge (Jinan)

- Jinan Jianbang Yellow River Bridge

- Beijing–Shanghai High-speed Railway Jinan Yellow River Bridge (Jinan–Dezhou)

- Beijing–Taipei Expressway Jinan Yellow River Bridge (Jinan–Dezhou)

- Beijing–Shanghai Railway Jinan Yellow River New Bridge (Jinan–Dezhou)

- Pingyin Yellow River Bridge (Jinan-Liaocheng)

Shandong–Henan

- Beijing–Kowloon Railway Sunkou Yellow River Bridge (Jining–Puyang)

- Juancheng Yellow River Highway Bridge (Heze–Puyang)

- Dongming Yellow River Highway Bridge (Heze–Puyang)

Henan

Shanxi–Henan

Shaanxi–Henan

Aquaculture

Although Yellow River is generally less suitable for aquaculture than the rivers of central and southern China, such as the Yangtze or the Pearl River, aquaculture is practiced in some areas along the Yellow River as well. An important aquaculture area is the riverside plain in Xingyang City, upstream from Zhengzhou. Since the development of fish ponds started in Xingyang's riverside Wangcun Town in 1986, the pond systems in Wangcun have grown to the total size of 15,000 mu (10 km2), making the town the largest aquaculture center in North China.[31]

A variety of the Chinese softshell turtle popular with China's gourmets is called the Yellow River Turtle (黄河鳖). Now-a-days most of Yellow River Turtles eaten in China's restaurants comes from turtle farms, which may or may not be located near the actual Yellow River. In 2007, construction started in Wangcun on a large farm for raising this turtle variety. With the capacity for raising 5 million turtles a year, the facility was expected to become Henan's largest farm of this kind.[32]

Pollution

On 25 November 2008, Tania Branigan of The Guardian filed a report "China's Mother River: the Yellow River", claiming that severe pollution has made one-third of China's Yellow River unusable even for agricultural or industrial use, due to factory discharges and sewage from fast-expanding cities.[33] The Yellow River Conservancy Commission had surveyed more than 8,384 mi (13,493 km) of the river in 2007 and said 33.8% of the river system registered worse than "level five" according the criteria used by the UN Environment Program.[dubious – discuss] Level five is unfit for drinking, aquaculture, industrial use, or even agriculture. The report said waste and sewage discharged into the system last year totaled 4.29b tons. Industry and manufacturing made up 70% of the discharge into the river with households accounting for 23% and just over 6% coming from other sources.[which?]

Yellow River in culture

In ancient times, it was believed that the Yellow River flowed from Heaven as a continuation of the Milky Way. In a Chinese legend, Zhang Qian is said to have been commissioned to find the source of the Yellow River. After sailing up-river for many days, he saw a girl spinning and a cow herd. Upon asking the girl where he was, she presented him with her shuttle with instructions to show it to the astrologer Yen Chün-p'ing. When he returned, the astrologer recognized it as the shuttle of the Weaving Girl (Vega), and, moreover, said that at the time Zhang received the shuttle, he had seen a wandering star interpose itself between the Weaving Girl and the cow herd (Altair).[34]

The provinces of Hebei and Henan derive their names from the Yellow River. Their names mean, respectively, "North of the River" and "South of the River".

- Mother river, China's Sorrow, and cradle of Chinese civilization.

Traditionally, it is believed that the Chinese civilization originated in the Yellow River basin. The Chinese refer to the river as "the Mother River" and "the cradle of the Chinese civilization". During the long history of China, the Yellow River has been considered a blessing as well as a curse and has been nicknamed both "China's Pride" (simplified Chinese: 中国的骄傲; traditional Chinese: 中國的驕傲; pinyin: Zhōngguóde Jiāo'ào) and "China's Sorrow"[35] (simplified Chinese: 中国的痛; traditional Chinese: 中國的痛; pinyin: Zhōngguóde Tòng).

- When the Yellow River flows clear.

Sometimes the Yellow River is poetically called the "Muddy Flow" (simplified Chinese: 浊流; traditional Chinese: 濁流; pinyin: Zhuó Liú). The Chinese idiom "when the Yellow River flows clear" is used to refer to an event that will never happen and is similar to the English expression "when pigs fly".

"The Yellow River running clear" was reported as a good omen during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, along with the appearance of such auspicious legendary beasts as qilin (an African giraffe brought to China by a Bengal embassy aboard Zheng He's ships in 1414) and zouyu (not positively identified) and other strange natural phenomena.[36]

See also

References

- ^ Yellow River (Huang He) Delta, China, Asia. Geol.lsu.edu (2000-02-28). Retrieved on 2013-02-04.

- ^ New York Times "A Troubled River Mirrors China's Path to Modernity". 19 November 2006 p. 4.

- ^ a b Baxter, Wm. H. & Sagart, Laurent. Template:PDFlink, p. 41. 2011. Accessed 11 October 2011.

- ^ Parker, Edward H. China: Her History, Diplomacy, and Commerce, from the Earliest Times to the Present Day, p. 11. Dutton (New York), 1917.

- ^ Geonames.de. "geonames.de: Huang He".

- ^ White, Matthew (2012). The Great Big Book of Horrible Things. W. W. Norton. p. 47. ISBN 9780393081923.

- ^ a b Gascoigne, Bamber and Gascoigne, Christina (2003) The Dynasties of China, Perseus Books Group, ISBN 0786712198

- ^ The Ice Bombers Move Against Mongolia. strategypage.com (29 March 2011)

- ^ a b c d e f Tregear, T. R. A Geography of China, p. 218. 1965.

- ^ "Flooding and communicable diseases fact sheet". World Health Organization. p. 2. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b Gernet, Jacques. Le monde chinois, p. 59. Map "4. Major states of the Chunqiu period (Spring and Autumn)". Template:Fr icon

English version: Gernet, Jacques (1996), A History of Chinese Civilization (Second edition ed.), Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-49781-7{{citation}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ "Qin Dynasty Map".

- ^ Allaby, Michael & Garrat, Richard. Facts on File Dangerous Weather Series: Floods, p. 142. Infobase Pub., 2003. ISBN 0-8160-5282-4. Accessed 15 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Elvin, Mark & Liu Cuirong (eds.) Studies in Environment and History: Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History, pp. 554 ff. Cambridge Uni. Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-56381-X. Accessed 15 Oct. 2011.

- ^ a b c Grousset, Rene. The Rise and Splendour of the Chinese Empire, p. 303. University of California Press, 1959.

- ^ a b c Tsai, Shih-Shan Henry. SUNY Series in Chinese Local Studies: The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. SUNY Press, 1996. ISBN 07914268ndfndfjspdec74, 9780791426876. Accessed 16 Oct 2012. Cite error: The named reference "eunuch" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Lorge, Peter Allan. War, Politics and Society in Early Modern China, 900–1795, p. 147. Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-415-31691-0.

- ^ Xu Xin. The Jews of Kaifeng, China: History, Culture, and Religion, p. 47. Ktav Publishing Inc, 2003. ISBN 978-0-88125-791-5.

- ^ a b International Rivers Report. "Before the Deluge". 2007.

- ^ Needham, Joseph. Science and Civilization in China. Vol. 1. Introductory Orientations, p. 68. Caves Books Ltd. (Taipei), 1986 ISBN 052105799X.

- ^ Lary, Diana. "The Waters Covered the Earth: China's War-Induced Natural Disaster". Op. cit. in Selden, Mark & So, Alvin Y., eds. War and State Terrorism: The United States, Japan, and the Asia-Pacific in the Long Twentieth Century, pp. 143–170. Rowman & Littlefield, 2004 ISBN 0742523918.

- ^ a b China's Yellow River, Part 1. The New York Times

- ^ Yellow River Conservancy Commission. Yellowriver.gov.cn. Retrieved on 2013-02-04.

- ^ Yellow River: Geographic and Historical Settings

- ^ Tregear, T.R. A Geography of China, p. 219. 1965

- ^ Yellow River Delta Shrinking 7.6 Square Kilometers Annually, China Daily 1 February 2005

- ^ Yellow River Upstream Important to West-East Power Transmission People's Daily, 14 December 2000

- ^ Yellow River Bridges (Baidu Encyclopedia) (in Chinese)

- ^ Yellow River Bridge Photos (Baidu) (in Chinese)

- ^ Yellow River Highway Bridge Photos (Baidu) (in Chinese)

- ^ 黄河畔的荥阳市万亩鱼塘 (Ten thousand of mu of fish ponds in the riverside Xingyang), 2011-09-30

- ^ 荥阳开建河南省最大黄河鳖养殖基地 (Construction started in Xingyang on the province's largest Yellow River Turtle farm), www.zynews.com, 2007-07-24

- ^ Branigan, Tania (25 November 2008). "One-third of China's Yellow River 'unfit for drinking or agriculture' Factory waste and sewage from growing cities has severely polluted major waterway, according to Chinese research". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- ^ This article incorporates text from entry Chang Chên-chou in A Chinese Biographical Dictionary by Herbert A. Giles (1898), a publication now in the public domain.

- ^ Cheng, Linsun and Brown, Kerry (2009) Berkshire encyclopedia of China, Berkshire Publishing Group, p. 1125 ISBN 978-0-9770159-4-8

- ^ Duyvendak, J.J.L. (1939). "The True Dates of the Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early Fifteenth Century". T'oung Pao, Second Series. 34 (5): 401–403. JSTOR 4527170.

External links

- Listen to the Yellow River Ballade from the Yellow River Cantata

- First raft descent of the Yellow River from its source in Qinghai to its mouth (1987)

- Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation Strategies in the Yellow River Basin – UNESCO report

- Works from the National Central Library about the Yellow River

- Illustrations of Guarding the Yellow River

- Illustrated Work on the Storage and Drainage Activities at the Lakes and Rivers of the Yellow River and the Grand Canal

- General Atlas Depicting the Conditions of the Yellow River Dykes in Henan Province