Zina

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

Zināʾ (زِنَاء) or zina (زِنًى or زِنًا) is an Islamic law concerning unlawful sexual relations between Muslims who are not married to one another through a nikah.[1] It includes extramarital sex and premarital sex,[2][page needed][3][page needed] such as adultery (consensual sexual relations outside marriage),[4] fornication (consensual sexual intercourse between two unmarried persons),[5] and homosexuality (consensual sexual relations between same-sex partners).[6]

In the four schools of Sunni fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), and the two schools of Shi'a fiqh, the term zināʾ is a sin of sexual intercourse that is not allowed by Sharia (Islamic law) and classed as a hudud crime (class of Islamic punishments that are fixed for certain crimes that are considered to be "claims of God").[7] To prove an act of zina, a qadi (religious judge) in a sharia court relies on an unmarried woman's pregnancy, the confession in the name of Allah, or four witnesses to the actual act of penetration. The last two types of prosecutions are uncommon; most prosecuted cases of zina in the history of Islam have been pregnant unmarried women.[8][page needed][9] In some schools of Islamic law, a pregnant woman accused of zina who denies sex was consensual must prove she was raped with four eyewitnesses testifying before the court. This has led to many cases where rape victims have been punished for zina.[10][11] Pressing charges of zina without required eyewitnesses is considered slander (Qadhf, القذف) in Islam, itself a hudud crime.[12][13]

The above sense of zina is not to be confused with the woman's name Zina or Zeina(زانيه). The name has a different linguistic root (Greek xen-), a different meaning ("guest, stranger"), is pronounced differently (either Zīnah or Zaynah), and is usually spelled differently.[14]

Islamic scriptures

Muslim scholars have historically considered zināʾ a hudud sin, or crime against God.[15] It is mentioned in both Quran and in the Hadiths.[citation needed]

Qur'an

The Qur'an deals with zināʾ in several places. First is the Qur'anic general rule that commands Muslims not to commit zināʾ:

"Nor come nigh to fornication/adultery: for it is a shameful (deed) and an evil, opening the road (to other evils)."

Most of the rules related to zināʾ, fornication/adultery, and false accusations from a husband to his wife or from members of the community to chaste women, can be found in Surat an-Nur (the Light). The sura starts by giving very specific rules about punishment for zināʾ:

"The woman and the man guilty of fornication,- flog each of them with a hundred stripes: Let not compassion move you in their case, in a matter prescribed by Allah, if ye believe in Allah and the Last Day: and let a party of the Believers witness their punishment."

"And those who accuse free women then do not bring four witnesses, flog them, (giving) eighty stripes, and do not admit any evidence from them ever; and these it is that are the transgressors. Except those who repent after this and act aright, for surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful."

Hadith

The public lashing and public lethal stoning punishment for zina are also prescribed in Hadiths, the books most trusted in Islam after Quran, particularly in Kitab Al-Hudud.[19][20][not specific enough to verify]

'Ubada b. as-Samit reported: Allah's Messenger as saying: Receive teaching from me, receive teaching from me. Allah has ordained a way for those women. When an unmarried male commits adultery with an unmarried female, they should receive one hundred lashes and banishment for one year. And in case of married male committing adultery with a married female, they shall receive one hundred lashes and be stoned to death.

Allah's Messenger awarded the punishment of stoning to death to the married adulterer and adulteress and, after him, we also awarded the punishment of stoning, I am afraid that with the lapse of time, the people may forget it and may say: We do not find the punishment of stoning in the Book of Allah, and thus go astray by abandoning this duty prescribed by Allah. Stoning is a duty laid down in Allah's Book for married men and women who commit adultery when proof is established, or if there is pregnancy, or a confession.

Ma'iz came to the Prophet and admitted having committed adultery four times in his presence so he ordered him to be stoned to death, but said to Huzzal: If you had covered him with your garment, it would have been better for you.

Hadith Sahih al Bukhari, another authentic source of sunnah, has several entries which refer to death by stoning.[21] For example,

Narrated 'Aisha: 'Utba bin Abi Waqqas said to his brother Sa'd bin Abi Waqqas, "The son of the slave girl of Zam'a is from me, so take him into your custody." So in the year of Conquest of Mecca, Sa'd took him and said. (This is) my brother's son whom my brother has asked me to take into my custody." 'Abd bin Zam'a got up before him and said, (He is) my brother and the son of the slave girl of my father, and was born on my father's bed." So they both submitted their case before Allah's Apostle. Sa'd said, "O Allah's Apostle! This boy is the son of my brother and he entrusted him to me." 'Abd bin Zam'a said, "This boy is my brother and the son of the slave girl of my father, and was born on the bed of my father." Allah's Apostle said, "The boy is for you, O 'Abd bin Zam'a!" Then Allah's Apostle further said, "The child is for the owner of the bed, and the stone is for the adulterer," He then said to Sauda bint Zam'a, "Veil (screen) yourself before him," when he saw the child's resemblance to 'Utba. The boy did not see her again till he met Allah.

Other hadith collections on zina between men and woman include:

- The stoning (Rajm) of a Jewish man and woman for having committed illegal sexual intercourse.[22]

- Abu Hurairah states that the Prophet, in a case of intercourse between a young man and a married woman, sentenced the woman to stoning[23] and the young man to flogging and banishment for a year;

- Umar al-Khattab asserts that there was a revelation to the effect that those who are muhsan (i.e. an adult, free, Muslim who has previously enjoyed legitimate sexual relations in matrimony regardless of whether the marriage still exists) and have unlawful intercourse are to be punished with stoning.

Homosexuality and zina

Islamic teachings (in the hadith tradition[24]) presume same-sex attraction, extol abstention and (in the Qur'an[6][24]) condemn consummation. Quran forbids homosexual relationships, in Al-Nisa, Al-Araf ( (verses 7:80-84, 11:69-83, 29:28-35 of the Qur'an using the story of Lot's people), and other surahs. For example,[6][24][25]

We also sent Lot: He said to his people: "Do ye commit lewdness such as no people in creation (ever) committed before you? For ye practice your lusts on men in preference to women: ye are indeed a people transgressing beyond bounds."

In another verse, the statement of prophet lot has been also pointed out,

Do you approach males among the worlds And leave what your Lord has created for you as mates? But you are a people transgressing.

— Quran 26:165–166, trans. Sahih International

Some scholars indicate this verse as the prescribed punishment for homosexuality in the Quran:

"If two (men) among you are guilty of lewdness, punish them both. If they repent and amend, Leave them alone; for Allah is Oft-returning, Most Merciful."

However, there are different interpretations of the last verse where who the Quran refers to as "two among you". Pakistani scholar Javed Ahmed Ghamidi sees it as a reference to premarital sexual relationships between men and women. In his opinion, the preceding Ayat of Sura Nisa deals with prostitutes of the time. He believes these rulings were temporary and were abrogated later when a functioning state was established and society was ready for permanent rulings, which came in Sura Nur, Ayat 2 and 3, prescribing flogging as a punishment for adultery. He does not see stoning as a prescribed punishment, even for married men, and considers the Hadiths quoted supporting that view to be dealing with either rape or prostitution, where the strictest punishment under Islam for spreading "fasad fil arz", meaning mischief in the land, referring to egregious acts of defiance to the rule of law was carried out.[citation needed]

The Hadiths consider homosexuality as zina, to be punished with death. For example, Abu Dawud states,[24][not specific enough to verify][27][page needed]

Narrated Abdullah ibn Abbas: The Prophet said: If you find anyone doing as Lot's people did,[28] kill the one who does it, and the one to whom it is done.

Narrated Abdullah ibn Abbas: If a man who is not married is seized committing sodomy, he will be stoned to death.

The discourse on homosexuality in Islam is primarily concerned with activities between men. There are, however, a few hadith mentioning homosexual behavior in women;[citation needed]The fuqaha' are agreed that "there is no hadd punishment for lesbianism, because it is not zina. Rather a ta’zeer punishment must be imposed, because it is a sin..'".[29] Although punishment for lesbianism is rarely mentioned in the histories, al-Tabari records an example of the casual execution of a pair of lesbian slavegirls in the harem of al-Hadi, in a collection of highly critical anecdotes pertaining to that Caliph's actions as ruler.[30] Some jurists viewed sexual intercourse as possible only for an individual who possesses a phallus;[31] hence those definitions of sexual intercourse that rely on the entry of as little of the corona of the phallus into a partner's orifice.[31] Since women do not possess a phallus and cannot have intercourse with one another, they are, in this interpretation, physically incapable of committing zinā.[31]

Rape and zina

Few hadiths have been found regarding rape in the time of Muhammad. The most popular transmitted hadith given below indicates the order of stoning for the rapist and no punishment for the raped.[32][33]

When a woman went out in the time of the Prophet for prayer, a man attacked her and overpowered (raped) her. She shouted and he went off, and when a man came by, she said: That (man) did such and such to me. And when a company of the emigrants came by, she said: That man did such and such to me. They went and seized the man whom they thought had had intercourse with her and brought him to her. She said: Yes, this is he. Then they brought him to the Messenger of Allah. When he (the Prophet) was about to pass sentence, the man who (actually) had assaulted her stood up and said: Messenger of Allah, I am the man who did it to her. He (the Prophet) said to her: Go away, for Allah has forgiven you. But he told the man some good words (AbuDawud said: meaning the man who was seized), and of the man who had had intercourse with her, he said: Stone him to death. He also said: He has repented to such an extent that if the people of Medina had repented similarly, it would have been accepted from them.

The hadiths declare rape of a free or slave woman as zina. For example,

Malik related to me from Ibn Shihab that gave a judgment that the rapist had to pay the raped woman her bride-price. Yahya said that he heard Malik say, "What is done in our community about the man who rapes a woman, virgin or non-virgin, if she is free, is that he must pay the bride-price of the like of her. If she is a slave, he must pay what he has diminished of her worth. The hadd-punishment in such cases is applied to the rapist, and there is no punishment applied to the raped woman. If the rapist is a slave, that is against his master unless he wishes to surrender him."

Even in cases where the raped woman is a free Muslim, the responsibility of proving the rape with four male eyewitnesses is on the rape victim.[8][page needed][34]

A judge may punish a potential rapist even if they do not confess or there are not four witnesses as a form of deterrence.[35]

Narrated Ibn Abdul Barr: The scholars are unanimously agreed that the rapist is to be subjected to the hadd punishment if there is clear evidence against him that he deserves the hadd punishment, or if he admits to that. Otherwise, he is to be punished (i.e., if there is no proof that the hadd punishment for zina may be carried out against him because he does not confess, and there are not four witnesses, then the judge may punish him and stipulate a punishment that will deter him and others like him). There is no punishment for the woman if it is true that he forced her and overpowered her, which may be proven by her screaming and shouting for help.

— Al-Istidhkaar, 7/146

Inclusions of the zināʾ definition

Zināʾ encompasses extramarital sex (between a married Muslim man and a married Muslim woman who are not married to one another), and premarital sex (between unmarried Muslim man and unmarried Muslim woman). In Islamic history, zina also included sex between Muslim man with a non-Muslim female slave, when the slave was not owned by that Muslim man.[8]

Zina also includes homosexuality, sodomy (anal sex or liwat), incest,[36] zoophilia[37] as well as any type of heterosexual sex between a man and a woman that does not involve penetration of penis into vagina (non-penetrative sex).[citation needed] Sharia, in describing zina, differentiates between an unmarried Muslim, a married Muslim (Muhsan) and a slave (Ma malakat aymanukum). The last two must be lethally stoned (rajm), while an unmarried Muslim must receive public lashing.[6][38] Heavy petting, kissing, caressing, masturbation and any form of sexual intimacy between individuals who are not married to each other are all considered a form of zina.[39][40]

There is some disagreement between Islamic scholars on the nature of zina and the kind of Sharia-required punishment for sexual acts between husband and wife such as oral sex, mutual masturbation, and having sex when sharia forbids sex to them such as during religious fasting, hajj and when the wife is having her menstrual period.[41] Abu Hanifa and Malik, and the two major fiqhs named after them, use the Principle of Najassah to argue irregular sex such as oral sex between husband and wife are abominable and disapproved (makruh) because it leads to impurity (Hadath-Akbar, حدث أکبر).[citation needed]

Accusation process and punishment

Islam requires evidence before a man or a woman can be punished for zināʾ. These are:[8][page needed][19][42]

- A confession by a Muslim of zināʾ. However, the person has a right to retract his/her confession; if confession is retracted, he/she is not punishable for zina (barring the presence of four male Muslim witnesses), or

- The woman is pregnant but not married, or

- The testimony of four reliable Muslim adult male eyewitnesses, all of whom must have witnessed the penetration at the same time.

"If any of your women are guilty of lewdness, Take the evidence of four (Reliable) witnesses from amongst you against them; and if they testify, confine them to houses until death do claim them, or Allah ordain for them some (other) way."

The four witnesses requirement for zina, that applies in case of an accusation against man or woman, is also revealed by Quranic verses 24:11 through 24:13 and various hadiths.[44][45] Some Islamic scholars state that the requirement of four male eyewitnesses was to address zina in public. There is disagreement between Islamic scholars on whether female eyewitnesses are acceptable witnesses in cases of zina (for other crimes, sharia considers two female witnesses equal the witness of one male).[34] In Sunni fiqhs of Islam, female Muslims, child and non-Muslim witnesses of zina are not acceptable.

Any uninvolved Muslim witness, or victim of non-consensual sexual intercourse, who accuses a Muslim of zina, but fails to produce four adult, pious male eyewitnesses (Tazikyah-al-shuhood) before a sharia court, commits the crime of false accusation (Qadhf, القذف), punishable with eighty lashes in public.[46][47]

Confession and four witness-based prosecutions of zina are rare. Most cases of prosecutions are when the woman becomes pregnant, or when she has been raped, seeks justice and the sharia authorities charge her for zina, instead of duly investigating the rapist.[10][48]

Some fiqhs (schools of Islamic jurisprudence) created the principle of shubha (doubt), wherein there would be no zina charges if a Muslim man claims he believed he was having sex with a woman he was married to or with a woman he owned as a slave.[19]

Sunni practice

All Sunni schools of jurisprudence agree that zināʾ is to be punished with lethal stoning if the offender is a married Muslim (muhsan). The punishment for zina by a muhsan is a hundred lashes followed by stoning to death in public. Persons who are not muhsan (unmarried Muslim) are punished for zina with one hundred lashes in public, but their life is spared.[27][page needed][49]

Pregnancy of an unmarried woman is regarded as evidence of zina.[8][page needed][19] Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence considers pregnancy as sufficient and automatic evidence. Other Sunni schools of jurisprudence rely on early Islamic scholars that state that a fetus can "sleep and stop developing for 5 years in a womb", and thus a woman who was previously married but now divorced may not have committed zina even if she delivers a baby years after her divorce.[50] These alternate fiqhs of Sunni Islam consider pregnancy of a never married woman as evidence of her committing the crime of zina. The position of modern Islamic scholars, however, varies from country to country. For example, in Malaysia which officially follows the non-Maliki Shafi'i fiqh, Section 23(2) through 23(4) of the Syariah (Sharia) Criminal Offences (Federal Territories) Act 1997 state,[51]

Section 23(2) - Any woman who performs sexual intercourse with a man who is not her lawful husband shall be guilty of an offence and shall on conviction be liable to a fine not exceeding five thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to whipping not exceeding six strokes or to any combination thereof.

Section 23(3) - The fact that a woman is pregnant out of wedlock as a result of sexual intercourse performed with her consent shall be prima facie evidence of the commission of an offence under subsection (2) by that woman.

Section 23(4) - For the purpose of subsection (3), any woman who gives birth to a fully developed child within a period of six qamariah months from the date of her marriage shall be deemed to have been pregnant out of wedlock.

— Islamic Laws of Malaysia[52]

The Malikis do not require Ihsan for the imposition of stoning. According to the Hanafis, homosexual intercourse can only be punished on the strength of tazir. Minimal proof for zināʾ is still the testimony of four male eyewitnesses, even in the case of homosexual intercourse.[citation needed]

Prosecution of extramarital pregnancy as zināʾ, as well as prosecution of rape victims for the crime of zina, have been the source of worldwide controversy in recent years.[53][54]

Shi'a practice

Again, minimal proof for zināʾ is the testimony of four male eyewitnesses. The Shi'is, however, also allow the testimony of women, if there is at least one male witness, testifying together with six women. All witnesses must have seen the act in its most intimate details, i.e. the penetration (like "a stick disappearing in a kohl container," as the fiqh books specify). If their testimonies do not satisfy the requirements, they can be sentenced to eighty lashes for unfounded accusation of fornication (kadhf). If the accused freely admits the offense, the confession must be repeated four times, just as in Sunni practice. Pregnancy of a single woman is also sufficient evidence of her having committed zina.[6]

Human rights controversy

The zināʾ and rape laws of countries under Sharia law are the subjects of a global human rights debate.[57][58]

Hundreds of women in Afghan jails are victims of rape or domestic violence.[54] This has been criticized as leading to "hundreds of incidents where a woman subjected to rape, or gang rape, was eventually accused of zināʾ" and incarcerated,[59] which is defended as punishment ordained by God.[citation needed]

In Pakistan, over 200,000 zina cases against women, under its Hudood laws, were under process at various levels in Pakistan's legal system in 2005.[53] In addition to thousands of women in prison awaiting trial for zina-related charges, there has been a severe reluctance to even report rape because the victim fears of being charged with zina.[60][not specific enough to verify]

Iran has prosecuted many cases of zina, and enforced public stoning to death of those accused between 2001 and 2010.[61][62]

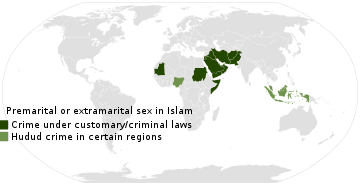

Zina laws are one of many items of reform and secularization debate with respect to Islam.[63][64] In early 20th century, under the influence of colonial era, many penal laws and criminal justice systems were reformed away from Sharia in Muslim-majority parts of the world. In contrast, in the second half of 20th century, after respective independence, governments from Pakistan to Morocco, Malaysia to Iran have reverted to Sharia with traditional interpretations of Islam’s sacred texts. Zina and hudud laws have been re-enacted and enforced.[65]

Contemporary human right activists refer this as a new phase in the politics of gender in Islam, the battle between forces of traditionalism and modernism in the Muslim world, and the use of religious texts of Islam through state laws to sanction and practice gender-based violence.[66][67]

In contrast to human rights activists, Islamic scholars and Islamist political parties consider 'universal human rights' arguments as imposition of a non-Muslim culture on Muslim people, a disrespect of customary cultural practices and sexual codes that are central to Islam. Zina laws come under hudud — seen as crime against Allah; the Islamists refer to this pressure and proposals to reform zina and other laws as ‘contrary to Islam’. Attempts by international human rights to reform religious laws and codes of Islam has become the Islamist rallying platforms during political campaigns.[68][69]

See also

- Islamic criminal jurisprudence

- Islamic sexual jurisprudence

- Namus

- Nikah mut‘ah

- Nikah urfi

- Ma malakat aymanukum and sex

- Rajm

- Repentance in Islam

- Sex and the law

References

- ^ R. Peters, Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd Edition, Edited by: P. Bearman et al., Brill, ISBN 978-9004161214, see article on Zinā

- ^ Muḥammad Salīm ʻAwwā (1982), Punishment in Islamic Law: A Comparative Study, American Trust Publications, ISBN 978-0892590155

- ^ Sakah Saidu Mahmud (2013), Sharia or Shura: Contending Approaches to Muslim Politics in Nigeria and Senegal, Lexington, ISBN 978-0739175644, Chapter 3

- ^ Ursula Smartt, Honour Killings Justice of the Peace, Vol. 170, January 2006, pp. 4-6

- ^ Z. Mir-Hosseini (2011), Criminalizing sexuality: zina laws as violence against women in Muslim contexts, Int'l Journal on Human Rights, 15, 7-16

- ^ a b c d e Camilla Adang (2003), Ibn Hazam on Homosexuality, Al Qantara, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 5-31

- ^ Julie Chadbourne (1999), Never wear your shoes after midnight: Legal trends under the Pakistan Zina Ordinance, Wisconsin International Law Journal, Vol. 17, pp. 179-234

- ^ a b c d e Kecia Ali (2006), Sexual Ethics and Islam, ISBN 978-1851684564, Chapter 4

- ^ M. Tamadonfar (2001), Islam, law, and political control in contemporary Iran, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 40(2): 205-220

- ^ a b A. Quraishi (1999), Her honour: an Islamic critique of the rape provisions in Pakistan's ordinance on zina, Islamic studies, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 403-431

- ^ Joseph Schacht, An Introduction to Islamic Law (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1973), pp. 176-183

- ^ Peters, Rudolph (2006). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: : Theory and Practice from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0521796705.

- ^ DeLong-Bas, Wahhabi Islam, 2004: 89-90

- ^ "Zina meaning and name origin". thinkbabynames.com. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ Reza Aslan (2004), "The Problem of Stoning in the Islamic Penal Code: An Argument for Reform", UCLA Journal of Islamic and Near East Law, Vol 3, No. 1, pp. 91-119

- ^ Quran 17:32

- ^ Quran 24:2

- ^ Quran 24:4–5

- ^ a b c d Z. Mir-Hosseini (2011), Criminalizing sexuality: zina laws as violence against women in Muslim contexts, SUR-Int'l Journal on Human Rights, 8(15), pp 7-33

- ^ Ziba Mir-Hosseini (2001), Marriage on Trial: A Study of Islamic Family Law, ISBN 978-1860646089, pp. 140-223

- ^ Hina Azam (2012), Rape as a Variant of Fornication (Zina) in Islamic Law: An Examination of the Early Legal Reports, Journal of Law & Religion, Volume 28, 441-459

- ^ Sahih al-Bukhari, 2:23:413

- ^ Understanding Islamic Law By Raj Bhala, LexisNexis, May 24, 2011

- ^ a b c d Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (1997), Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature, ISBN 978-0814774687, New York University Press, pp. 88-94

- ^ Michaelson, Jay (2011). God Vs. Gay? The Religious Case for Equality. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780807001592.

- ^ Quran 4:16

- ^ a b Mohamed S. El-Awa (1993), Punishment In Islamic Law, American Trust Publications, ISBN 978-0892591428

- ^ The sunnah and surah describe the Lot's people in context of homosexuality and sodomy such as any form of sex between a man and woman that does not involve penetration of man's penis in woman's vagina.

- ^ Islamqa.com

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. (1989). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30: The 'Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid A.D. 785-809/A.H. 169-193. SUNY Press.

- ^ a b c Omar, Sara. "The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Law". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ Bouhdiba, Abdelwahab (1985). Sexuality in Islam. Saqi Books. p. 288. ISBN 9780863564932.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Aftab (2006). Sex and Sexuality in Islam. The University of Michigan: Nashriyat. p. 764. ISBN 9789698983048.

- ^ a b A. Engineer (2004), The Rights of Women in Islam, 3rd Edition, ISBN 978-8120739338, pp. 80-86

- ^ "Rape against Muslim Women". www.irfi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ Jami` at-Tirmidhi,17:46

- ^ Jami` at-Tirmidhi,17:38

- ^ Jan Otto, Sharia Incorporated, Leiden University Press, ISBN 978-9087280574

- ^ What constitutes Zina? Universiti Sains Isam Malaysia (2002)

- ^ Quran 23:5–7

- ^ Quran 2:222

- ^ Sahih Muslim, 17:4194

- ^ Quran 4:15

- ^ Quran 24:13, Kerby Anderson (2007), Islam, Harvest House ISBN 978-0736921176, pp. 87-88

- ^ Al-Muwatta, 36 19.17, Al-Muwatta, 36 19.18, Al-Muwatta, 41 1.7

- ^ J. Campo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, ISBN 978-0816054541, pp. 13-14

- ^ R. Mehdi (1997), The offence of rape in the Islamic law of Pakistan, Women Living under Muslim Laws: Dossier, 18, pp. 98-108

- ^ A.S. Sidahmed (2001), Problems in contemporary applications of Islamic criminal sanctions: The penalty for adultery in relation to women, British journal of middle eastern studies, 28(2): 187-204

- ^ F. Vogel, Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- ^ JANSEN, W. (2000), Sleeping in the Womb: Protracted Pregnancies in the Maghreb, The Muslim World, n. 90, p. 218-237

- ^ Laws of Malaysia SYARIAH CRIMINAL OFFENCES (FEDERAL TERRITORIES) ACT 1997, Government of Malaysia

- ^ CEDAW and Malaysia Women's Aid Organization, United Nations Report (April 2012), page 83-85

- ^ a b Pakistan Human Rights Watch (2005)

- ^ a b Afghanistan - Moral Crimes Human Rights Watch (2012); Quote "Some women and girls have been convicted of zina, sex outside of marriage, after being raped or forced into prostitution. Zina is a crime under Afghan law, punishable by up to 15 years in prison."

- ^ Ziba Mir-Hosseini (2011), Criminalizing sexuality: zina laws as violence against women in Muslim contexts, SUR - Int'l Journal on Human Rights, 15, pp. 7-31

- ^ Haideh Moghissi (2005), Women and Islam: Part 4 Women, sexuality and sexual politics in Islamic cultures, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-32420-3

- ^ KUGLE (2003), Sexuality, diversity and ethics in the agenda of progressive Muslims, In: SAFI, O. (Ed.). Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, Oxford: Oneworld. pp. 190-234

- ^ LAU, M. (2007), Twenty-Five Years of Hudood Ordinances: A Review, Washington and Lee Law Review, n. 64, pp. 1291-1314

- ^ National Commission on the status of women's report on Hudood Ordinance 1979

- ^ Rahat Imran (2005), Legal Injustices: The Zina Hudood Ordinance of Pakistan and Its Implications for Women, Journal of International Women's Studies, Vol. 7, Issue 2, pp 78-100

- ^ BAGHI, E. (2007) The Bloodied Stone: Execution by Stoning International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran

- ^ End Executions by Stoning - An Appeal AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, 15 Jan 2010

- ^ Rehman J. (2007), The sharia, Islamic family laws and international human rights law: Examining the theory and practice of polygamy and talaq, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 21(1), pp. 108-127

- ^ SAFWAT (1982), Offences and Penalties in Islamic Law. Islamic Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 149-181

- ^ Weiss A. M. (2003), Interpreting Islam and women's rights implementing CEDAW in Pakistan, International Sociology, 18(3), pp. 581-601

- ^ KAMALI (1998), Punishment in Islamic Law: A Critique of the Hudud Bill of Kelantan Malaysia, Arab Law Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 203-234

- ^ QURAISHI, A (1996), Her Honor: An Islamic Critique of the Rape Laws of Pakistan from a Woman-Sensitive Perspective, Michigan Journal of International Law, vol. 18, pp. 287-320

- ^ A. SAJOO (1999), Islam and Human Rights: Congruence or Dichotomy, Temple International and Comparative Law Journal, vol. 4, pp. 23-34

- ^ K. ALI (2003), Progressive Muslims and Islamic Jurisprudence: The Necessity for Critical Engagement with Marriage and Divorce Law, In: SAFI, O. (Ed.). Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, Oxford: Oneworld, pp. 163-189

- DeLong-Bas, Natana J. (2004). Wahhabi Islam: From Revival and Reform to Global Jihad (First ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0-19-516991-3.

Further reading

- Calder, Norman, Colin Imber, and R. Gleave. Islamic Jurisprudence in the Classical Era. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge UP, 2010.

- Johnson, Toni, and Lauren Vriens, "Islam: Governing Under Sharia.", Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., 24 Oct. 2011. Web. 19 Nov. 2011.

- Karamah: Muslim Women Lawyers for Human Rights, "Zina, Rape, and Islamic Law: An Islamic Legal Analysis of the Rape Laws in Pakistan." 26 Nov. 2011.

- Khan, Shahnaz. "Locating The Feminist Voice: The Debate On The Zina Ordinance." Feminist Studies 30.3 (2004): 660-685. Academic Search Complete. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen. The Cambridge Companion to the Qurʼān. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2006

- Peters, R. "Zinā or Zināʾ (a.)." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman;, Th. Bianquis;, C.E. Bosworth;, E. van Donzel; and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2011. Brill Online. UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN. 17 November 2011

- Peters, R. "The Islamization of criminal law: A comparative analysis", in WI, xxxiv (1994), 246-74.

- Quraishi, Asifa. "Islamic Legal Analysis of Zina Punishment of Bariya Ibrahim Magazu, Zamfara, Nigeria." Muslim Women's League. Muslim Women's League, 20 Jan. 2001

External links

- Zina prosecution in Katsina State, Northern Nigeria Proceedings and Judgments in the Amina Lawal Case (2002)

- Sharia Law

- False Accusation Under Islamic Law

- Articles and Opinions: American Muslims need to speak out against violations of Islamic Shariah law (Asma Society)

- Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary - Zina Chapter, p. 43, at Google Books, Hisham M. Ramadan

- Afghanistan: Surge in Women Jailed for ‘Moral Crimes’ Zina in Afghanistan, Human Rights Watch (May 21, 2013)

- Yet another case of stoning; Sudan women continue to be caught up in the chaos Zina victims, Sudan Tribune (2012)

- MAURITANIA: Justice not working for rape victims Zina in Mauritania, IRIN Africa, United Nations

- Mukhtar Mai - history of a rape case, Pakistan, BBC News

- Fate of another royal found guilty of adultery Zina in Saudi Arabia, The Independent (2009), UK

- Zina, Evidence and Stoning Punishment The Independent (September 2013)