Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: Difference between revisions

→Neuromuscular: Removed text on Babinski response. Reference was to hos to perform Babinski evaluation, not presence in SBMA. No other reference reports Babinski sign in SBMA |

Extensive rewrite of signs and symptoms. Converted table format to paragraphs with links to other articles and plain english explanation of terms |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Signs and symptoms== |

==Signs and symptoms== |

||

Neuromuscular symptoms include muscle weakness and wasting of the limb, bulbar and respiratory muscles, tremor, fasciculations, muscle cramps, speech and swallowing difficulties, decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes, and sensory neuropathy. Other manifestations of SBMA include androgen insensitivity (gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, reduced fertility, testicular atrophy), and metabolic impacts (glucose resistance, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver disease) <ref name=":4">{{Cite journal |last=Pradat |first=Pierre-François |last2=Bernard |first2=Emilien |last3=Corcia |first3=Philippe |last4=Couratier |first4=Philippe |last5=Jublanc |first5=Christel |last6=Querin |first6=Giorgia |last7=Morélot Panzini |first7=Capucine |last8=Salachas |first8=François |last9=Vial |first9=Christophe |last10=Wahbi |first10=Karim |last11=Bede |first11=Peter |last12=Desnuelle |first12=Claude |date=2020-04-10 |title=The French national protocol for Kennedy’s disease (SBMA): consensus diagnostic and management recommendations |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13023-020-01366-z |journal=Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases |volume=15 |issue=1 |doi=10.1186/s13023-020-01366-z |issn=1750-1172}}</ref><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":7" />. |

|||

Individuals with SBMA have muscle cramps and progressive weakness due to [[Degeneration (medical)|degeneration]] of motor neurons in the brain stem and spinal cord. Ages of onset and severity of manifestations in affected males vary from adolescence to old age, but most commonly develop in middle adult life. The syndrome has neuromuscular and [[endocrine]] manifestations.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

'''Neuromuscular''' |

|||

Early signs often include weakness of tongue and mouth muscles, [[fasciculations]], and gradually increasing weakness of limb muscles with muscle wasting. Neuromuscular management is supportive, and the disease progresses very slowly, but can eventually lead to extreme disability.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Grunseich|first1=Christopher|last2=Fischbeck|first2=Kenneth H.|date=2015-11-01|title=Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy|journal=Neurologic Clinics|volume=33|issue=4|pages=847–854|doi=10.1016/j.ncl.2015.07.002|issn=1557-9875|pmc=4628725|pmid=26515625}}</ref> Further signs and symptoms include: |

|||

[[File:Human chromosome X - 550 bphs.png|150px|thumb|Ideogram of human X chromosome.]] |

|||

{{columns-list|colwidth=30em| |

|||

'''Neurological''' |

|||

* Bulbar signs: bulbar muscles are those supplied by the motor nerves from the brain stem, which control swallowing, [[speech]], and other functions of the throat.<ref name=gene/> |

|||

* [[Lower motor neuron]] signs: lower motor neurons are those in the [[brainstem]] and spinal cord that directly supply the muscles, loss of lower motor neurons leads to weakness and wasting of the muscle.<ref name=gene/> |

|||

* [[Respiratory]] musculature weakness<ref name=gene/> |

|||

* Action [[tremor]]<ref name=gene/> |

|||

* Decreased or absent deep [[tendon]] reflexes <ref name=gene/> |

|||

SBMA patients develop limb weakness which often begins in the pelvic or shoulder regions between 30 and 50 years of age <ref name=":33" />. Muscle strength declines slowly, at a rate of approximately 2% per year based on quantitative muscle assessment <ref name=":33" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fernández-Rhodes |first=Lindsay E |last2=Kokkinis |first2=Angela D |last3=White |first3=Michelle J |last4=Watts |first4=Charlotte A |last5=Auh |first5=Sungyoung |last6=Jeffries |first6=Neal O |last7=Shrader |first7=Joseph A |last8=Lehky |first8=Tanya J |last9=Li |first9=Li |last10=Ryder |first10=Jennifer E |last11=Levy |first11=Ellen W |last12=Solomon |first12=Beth I |last13=Harris-Love |first13=Michael O |last14=La Pean |first14=Alison |last15=Schindler |first15=Alice B |date=2011-02-01 |title=Efficacy and safety of dutasteride in patients with spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1474442210703215 |journal=The Lancet Neurology |language=en |volume=10 |issue=2 |pages=140–147 |doi=10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70321-5 |issn=1474-4422}}</ref>. Muscle weakness often begins in proximal muscles, with most patients first noticing weakness in their lower limbs<ref name=":4" /><ref name=":5" />. |

|||

'''Muscular''' |

|||

* [[Cramps]]: muscle spasms<ref name="gene">{{Cite book|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1333/|title=Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy|last=La Spada|first=Albert|date=1993-01-01|publisher=University of Washington, Seattle|editor-last=Pagon|editor-first=Roberta A.|location=Seattle (WA)|pmid=20301508|editor-last2=Adam|editor-first2=Margaret P.|editor-last3=Ardinger|editor-first3=Holly H.|editor-last4=Wallace|editor-first4=Stephanie E.|editor-last5=Amemiya|editor-first5=Anne|editor-last6=Bean|editor-first6=Lora J.H.|editor-last7=Bird|editor-first7=Thomas D.|editor-last8=Fong|editor-first8=Chin-To|editor-last9=Mefford|editor-first9=Heather C.}} Update: July 3, 2014</ref> |

|||

* Muscular atrophy: loss of muscle bulk that occurs when the lower motor neurons do not stimulate the muscle adequately<ref name=gene/> |

|||

Tremor, fasciculations, and cramps are common early symptoms of SBMA. [[Tremor]] is an involuntary, somewhat rhythmic, muscle contraction and relaxation involving oscillations or twitching movements. In SBMA patients, tremor is most common in the hands, but also occur in the head, voice and lower limbs, and maybe observed ten years prior to muscle weakness <ref name=":33" /><ref name=":4" />. [[Fasciculation]], or fleeting muscle twitches visible under the skin, is a spontaneous, involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation, and is especially noticeable in the face and tongue of SBMA patients. Lingual atrophy occurs later in the course of the disease, but the tongue may develop an unusual shape due to coexisting denervation and reinnervation. A [[cramp]] is a sudden, involuntary, painful skeletal muscle contraction of skeletal muscle, and common in motor neuron disorders (e.g., [[ALS]], SBMA, ) |

|||

'''Endocrine''' |

|||

* [[Gynecomastia]]: male breast enlargement<ref name=emed/> |

|||

* [[Erectile dysfunction]]<ref name="emed">{{Cite web | url=http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/715991 | title=Clinical Features of Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy}}</ref> |

|||

* Reduced [[fertility]]<ref name=emed/> |

|||

* [[Testicular]] atrophy: testicles become smaller and less functional<ref name="omim">{{Cite web|url=https://omim.org/entry/313200|title=OMIM Entry - # 313200 - SPINAL AND BULBAR MUSCULAR ATROPHY, X-LINKED 1; SMAX1|website=omim.org|access-date=2016-03-23}}</ref> |

|||

Bulbar symptoms (weakness of the facial and tongue muscles) typically follow limb manifestations and may start with difficulty with speech articulation ([[dysarthria]]) before swallowing difficulty ([[dysphagia]]) <ref name=":4" /><ref name=":2" /><ref name=":33" />. Dysarthria is common, with hypernasality due to incomplete lifting of soft palate, but typically remains relatively mild and seldom leads to the loss of oral communication <ref name=":4" />. Signs of dysphagia include difficulty controlling solids, liquids or saliva in the mouth, coughing and choking. As the disease progresses, there is increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, which is the leading cause of death in SBMA patients <ref name=":4" />. Up to half of all patients experience [[laryngospasm]], an uncontrolled contraction (spasm) of the vocal folds, with a sense of choking, and feel that the air cannot enter or exit the airways for long seconds. Laryngospasms are often followed by a high-pitched breathing sound ([[stridor]]) due to rapid and vigorous contraction of the laryngeal sphincters. This is a frightening and hugely distressing experience, but rarely escalates to prolonged or serious episodes <ref name=":4" />. |

|||

'''Other''' |

|||

* Late onset: individuals usually develop symptoms in their late 30s or afterwards (rarely is it seen in adolescence) <ref name=gene/> |

|||

}} |

|||

In SBMA, deep tendon reflexes are diminished or absent. Sensory involvement results in degeneration of dorsal root ganglion cells with reduced vibratory sensation (distally in the legs), neuropathic pain, and numbness <ref name=":33" />. There are sporadic reports of certain psychological traits (lack of self-confidence, emotional flattening, and poor concentration), but detailed neuropsychological examination of 64 SBMA patients did not detect any abnormalities <ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Marcato |first=S. |last2=Kleinbub |first2=J. R. |last3=Querin |first3=G. |last4=Pick |first4=E. |last5=Martinelli |first5=I. |last6=Bertolin |first6=C. |last7=Cipolletta |first7=S. |last8=Pegoraro |first8=E. |last9=Sorarù |first9=G. |last10=Palmieri |first10=A. |date=2018-09-11 |title=Unimpaired Neuropsychological Performance and Enhanced Memory Recall in Patients with Sbma: A Large Sample Comparative Study |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-32062-5 |journal=Scientific Reports |volume=8 |issue=1 |doi=10.1038/s41598-018-32062-5 |issn=2045-2322}}</ref>. |

|||

===Homozygous females=== |

|||

[[Homozygous]] females, both of whose [[X chromosomes]] have a mutation leading to CAG expansion of the ''AR'' gene, have been reported to show only mild symptoms of muscle cramps and twitching. No endocrinopathy has been described.<ref name=omim/> |

|||

'''Androgen insensitivity''' |

|||

Loss of AR function in SBMA patients results in partial androgen insensitivity, including gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, infertility and testicular atrophy <ref name=":4" /><ref name=":7" />. Patients with complete [[Androgen insensitivity syndrome]] do not show the neuromuscular symptoms of SBMA, indicating these symptoms are not caused by a loss of AR function <ref name=":33" />. |

|||

Gynecomastia, excessive enlargement of male breasts, is observed in about three quarters of SBMA patients. It typically becomes apparent after puberty, and is often the first evidence of this disease <ref name=":7" />. Erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, infertility and testicular atrophy are common <ref name=":6">{{Cite journal |last=Dejager |first=S. |date=2002-08-01 |title=A Comprehensive Endocrine Description of Kennedy's Disease Revealing Androgen Insensitivity Linked to CAG Repeat Length |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1210/jc.87.8.3893 |journal=Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism |volume=87 |issue=8 |pages=3893–3901 |doi=10.1210/jc.87.8.3893 |issn=0021-972X}}</ref>. One of the most disease-specific endocrine indices of SBMA is the androgen sensitivity index ([[luteinizing hormone]] / [[testosterone]]) which is elevated in 64% of cases, indicating both endocrine and exocrine testicular dysfunction <ref name=":4" /><ref name=":6" />. |

|||

'''Metabolic Disturbances''' |

|||

Metabolic disturbances have also been reported in SBMA patients, with increased risk of insulin resistance, fatty liver disease, hyperlipidemia, and electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities. Impaired glucose homeostasis is a common feature of SBMA, and recent study found a significant correlation between insulin resistance and motor dysfunction in SBMA [33]. In a group of 22 patients with SBMA, evidence of fatty liver disease was detected by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In a second group, liver dome magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurements were increased in participants with SBMA relative to age- and sex-matched controls <ref name=":4" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Guber |first=Robert D. |last2=Takyar |first2=Varun |last3=Kokkinis |first3=Angela |last4=Fox |first4=Derrick A. |last5=Alao |first5=Hawwa |last6=Kats |first6=Ilona |last7=Bakar |first7=Dara |last8=Remaley |first8=Alan T. |last9=Hewitt |first9=Stephen M. |last10=Kleiner |first10=David E. |last11=Liu |first11=Chia-Ying |last12=Hadigan |first12=Colleen |last13=Fischbeck |first13=Kenneth H. |last14=Rotman |first14=Yaron |last15=Grunseich |first15=Christopher |date=2017-12-12 |title=Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy |url=https://n.neurology.org/content/89/24/2481 |journal=Neurology |language=en |volume=89 |issue=24 |pages=2481–2490 |doi=10.1212/WNL.0000000000004748 |issn=0028-3878 |pmid=29142082}}</ref>. SBMA patients may have higher frequency of Brugada syndrome and other electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, which if not detected, can lead to sudden death. There are no reports of cardiomyopathy. However, there are indication that SBMA patients may be more likely to have high blood pressure and elevated total cholesterol and triglycerides <ref name=":33" /><ref name=":4" />. |

|||

==Genetics== |

==Genetics== |

||

| Line 75: | Line 67: | ||

==Management== |

==Management== |

||

In terms of the management of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, no cure is known and treatment is supportive. [[Physical medicine and rehabilitation|Rehabilitation]] to slow muscle weakness can prove positive, though the prognosis indicates some individuals will require the use of a wheelchair in later stages of life.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Kennedys-Disease-Information-Page|title=Kennedy's Disease Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)|website=NIH|access-date=2016-03-23}}</ref> Preferred nonsurgical treatment occurs due to the high rate of repeated [[joint dislocation|dislocation]] of the [[hip]].<ref name=emed/> No cure for SBMA is known.<ref name="pmid16389310">{{Cite journal|last1=Merry|first1=D. E.|year=2005|title=Animal Models of Kennedy Disease|journal=NeuroRx|volume=2|issue=3|pages=471–479|doi=10.1602/neurorx.2.3.471|pmc=1144490|pmid=16389310}}</ref><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":052" /> |

In terms of the management of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, no cure is known and treatment is supportive. [[Physical medicine and rehabilitation|Rehabilitation]] to slow muscle weakness can prove positive, though the prognosis indicates some individuals will require the use of a wheelchair in later stages of life.<ref name=":5">{{Cite web|url=https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Kennedys-Disease-Information-Page|title=Kennedy's Disease Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)|website=NIH|access-date=2016-03-23}}</ref> Preferred nonsurgical treatment occurs due to the high rate of repeated [[joint dislocation|dislocation]] of the [[hip]].<ref name=emed/> No cure for SBMA is known.<ref name="pmid16389310">{{Cite journal|last1=Merry|first1=D. E.|year=2005|title=Animal Models of Kennedy Disease|journal=NeuroRx|volume=2|issue=3|pages=471–479|doi=10.1602/neurorx.2.3.471|pmc=1144490|pmid=16389310}}</ref><ref name=":12" /><ref name=":052" /> |

||

==History== |

==History== |

||

Revision as of 20:18, 2 January 2023

| Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy | |

|---|---|

| Other names | spinobulbar muscular atrophy, bulbo-spinal atrophy, X-linked bulbospinal neuropathy (XBSN), X-linked spinal muscular atrophy type 1 (SMAX1), Kennedy's disease (KD), and many other names[1] |

| |

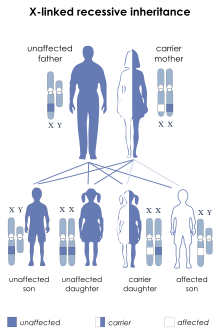

| SBMA is inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern. | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Symptoms | Muscles cramps[2] |

| Causes | Mutation in the AR gene[3] |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical features, Family history[4] |

| Treatment | Physical therapy [4] |

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA), popularly known as Kennedy's disease, is a debilitating neurodegenerative disorder resulting in muscle cramps and progressive weakness due to degeneration of motor neurons in the brainstem and spinal cord and muscle wasting.[5][6]

The condition is associated with mutation of the androgen receptor (AR) gene[7][8] and is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. As with many genetic disorders, no cure is known, although research continues. Because of its endocrine manifestations related to the impairment of the AR gene, patients with SBMA develop partial symptoms of androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) in addition to neuromuscular degeneration. SBMA is related to other neurodegenerative diseases caused by similar mutations, such as Huntington's disease.[9] The prevalence of SBMA has been estimated at 2.6:100,000 males.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Neuromuscular symptoms include muscle weakness and wasting of the limb, bulbar and respiratory muscles, tremor, fasciculations, muscle cramps, speech and swallowing difficulties, decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes, and sensory neuropathy. Other manifestations of SBMA include androgen insensitivity (gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, reduced fertility, testicular atrophy), and metabolic impacts (glucose resistance, hyperlipidemia, fatty liver disease) [11][6][12].

Neuromuscular

SBMA patients develop limb weakness which often begins in the pelvic or shoulder regions between 30 and 50 years of age [13]. Muscle strength declines slowly, at a rate of approximately 2% per year based on quantitative muscle assessment [13][14]. Muscle weakness often begins in proximal muscles, with most patients first noticing weakness in their lower limbs[11][15].

Tremor, fasciculations, and cramps are common early symptoms of SBMA. Tremor is an involuntary, somewhat rhythmic, muscle contraction and relaxation involving oscillations or twitching movements. In SBMA patients, tremor is most common in the hands, but also occur in the head, voice and lower limbs, and maybe observed ten years prior to muscle weakness [13][11]. Fasciculation, or fleeting muscle twitches visible under the skin, is a spontaneous, involuntary muscle contraction and relaxation, and is especially noticeable in the face and tongue of SBMA patients. Lingual atrophy occurs later in the course of the disease, but the tongue may develop an unusual shape due to coexisting denervation and reinnervation. A cramp is a sudden, involuntary, painful skeletal muscle contraction of skeletal muscle, and common in motor neuron disorders (e.g., ALS, SBMA, )

Bulbar symptoms (weakness of the facial and tongue muscles) typically follow limb manifestations and may start with difficulty with speech articulation (dysarthria) before swallowing difficulty (dysphagia) [11][6][13]. Dysarthria is common, with hypernasality due to incomplete lifting of soft palate, but typically remains relatively mild and seldom leads to the loss of oral communication [11]. Signs of dysphagia include difficulty controlling solids, liquids or saliva in the mouth, coughing and choking. As the disease progresses, there is increased risk of aspiration pneumonia, which is the leading cause of death in SBMA patients [11]. Up to half of all patients experience laryngospasm, an uncontrolled contraction (spasm) of the vocal folds, with a sense of choking, and feel that the air cannot enter or exit the airways for long seconds. Laryngospasms are often followed by a high-pitched breathing sound (stridor) due to rapid and vigorous contraction of the laryngeal sphincters. This is a frightening and hugely distressing experience, but rarely escalates to prolonged or serious episodes [11].

In SBMA, deep tendon reflexes are diminished or absent. Sensory involvement results in degeneration of dorsal root ganglion cells with reduced vibratory sensation (distally in the legs), neuropathic pain, and numbness [13]. There are sporadic reports of certain psychological traits (lack of self-confidence, emotional flattening, and poor concentration), but detailed neuropsychological examination of 64 SBMA patients did not detect any abnormalities [11][16].

Androgen insensitivity

Loss of AR function in SBMA patients results in partial androgen insensitivity, including gynecomastia, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, infertility and testicular atrophy [11][12]. Patients with complete Androgen insensitivity syndrome do not show the neuromuscular symptoms of SBMA, indicating these symptoms are not caused by a loss of AR function [13].

Gynecomastia, excessive enlargement of male breasts, is observed in about three quarters of SBMA patients. It typically becomes apparent after puberty, and is often the first evidence of this disease [12]. Erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, infertility and testicular atrophy are common [17]. One of the most disease-specific endocrine indices of SBMA is the androgen sensitivity index (luteinizing hormone / testosterone) which is elevated in 64% of cases, indicating both endocrine and exocrine testicular dysfunction [11][17].

Metabolic Disturbances

Metabolic disturbances have also been reported in SBMA patients, with increased risk of insulin resistance, fatty liver disease, hyperlipidemia, and electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities. Impaired glucose homeostasis is a common feature of SBMA, and recent study found a significant correlation between insulin resistance and motor dysfunction in SBMA [33]. In a group of 22 patients with SBMA, evidence of fatty liver disease was detected by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. In a second group, liver dome magnetic resonance spectroscopy measurements were increased in participants with SBMA relative to age- and sex-matched controls [11][18]. SBMA patients may have higher frequency of Brugada syndrome and other electrocardiogram (ECG) abnormalities, which if not detected, can lead to sudden death. There are no reports of cardiomyopathy. However, there are indication that SBMA patients may be more likely to have high blood pressure and elevated total cholesterol and triglycerides [13][11].

Genetics

SBMA is a hereditary syndrome, inherited in an X-linked recessive manner.[7] The AR gene, located in the X chromosome, contains a tract of CAG repeats within the region coding for the N-terminal domain.[6] The number of repeats varies among individuals. Healthy males carry up to 34 repeats. From 35 to around 46 repeats, penetrance (the possibility that the individual manifests the disease) gradually increases, approaching a maximum value (full penetrance).[10] Therefore, males bearing 35 to 46 CAG repeats are at intermediate but increasing risk for developing SBMA. Males bearing 47 or more repeats have nearly 100% risk of developing SBMA.[10] Other, still unidentified genetic factors may also play a role in disease manifestation and symptoms’ severity. Genetic founder effects are likely to be responsible for the higher prevalence of SBMA observed in certain geographic regions.[19]

Pathophysiology

SBMA is caused by expansion of a CAG repeat in the first exon of the androgen receptor gene (trinucleotide repeats).[20][21] The CAG repeat encodes a polyglutamine tract in the androgen receptor protein.[22][20] Patients with longer CAG expansions tend to develop more severe disease manifestations and earlier disease onset. The repeat expansion likely causes a toxic gain of function in the receptor protein, since loss of receptor function in androgen insensitivity syndrome does not cause motor neuron degeneration.[23]

Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy may share mechanistic features with other disorders caused by polyglutamine expansion, such as Huntington's disease.[22] For example, the polyglutamine expanded androgen receptor is known to misfold and aggregate.[13] This aggregation of the mutant protein is dependent on the presence of testosterone, the ligand for the androgen receptor.[13] As a result, though female carriers of the CAG repeat expansion express the polyglutamine androgen receptor protein, due to lower levels of testosterone they do not develop disease.[20] Similarly, in animal models of SBMA castration dramatically reduces disease phenotype.[13] Polyglutamine expansion of the androgen receptor has a number of known cellular and molecular consequences, including disrupting cellular signaling pathways, protein homeostasis, and cellular trafficking.[24][13]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of SBMA is based on identifying the number of CAG repeats in the AR gene using molecular techniques such as PCR. The accuracy of such techniques is nearly 100%.[7]

Prognosis

A 2006 study followed 223 patients for up to twenty years. Of these, 15 died, with a median age of 65 years. The authors tentatively concluded that this is in line with a previously reported estimate of a shortened life expectancy of 10–15 years (12 in their data).[25] Greater than fifty percent of individuals with SBMA develop lower limb weakness.[26] Weakness most often begins between the age of 30 and 60.[20] Weakness typically becomes severe enough to necessitate a wheelchair about twenty years following the onset of symptoms.[20]

Management

In terms of the management of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy, no cure is known and treatment is supportive. Rehabilitation to slow muscle weakness can prove positive, though the prognosis indicates some individuals will require the use of a wheelchair in later stages of life.[15] Preferred nonsurgical treatment occurs due to the high rate of repeated dislocation of the hip.[27] No cure for SBMA is known.[28][21][20]

History

SBMA was first described in Japanese literature in 1897 by Hiroshi Kawahara in a case report detailing progressive bulbar palsy in two brothers.[26][20] Information on the clinical course, X-linked inheritance patterns, and key pathologic features was later documented by William R. Kennedy in 1968.[5] Onset of disease in mid-life and lack of symptoms in heterozygous female carriers was further described by Anita Harding in 1982.[20] In 1986, the causative gene of SBMA was shown to be present on the proximal arm of the X chromosome by Kurt Fischbeck,[26] though the exact gene causing SBMA had not yet been characterized. In 1991, it was discovered that the AR gene is involved in the disease process, and that expansion of a CAG repeat in the AR gene causes disease.[7]

Research

Research in SBMA is broad, and covers a number of aspects of the disorder. Below is a summary of a few areas of ongoing research in SBMA:

Aggregation

The polyglutamine androgen receptor does not fold properly, and subsequently forms protein aggregates with other proteins. This is a gain of new function conferred by the polyglutamine tract, as the non-polyglutamine expanded androgen receptor does not form these aggregates.[29] Several proteins key to normal cellular function have been found to be sequestered within these aggregates, including CREB-BP, Hsp70, Hsp40, and components of the ubiquitin proteasome system.[13] It is thought that loss of sufficient supply of these and other key proteins contributes to the pathogenesis of the disease, though further research is ongoing.[29]

Post-Translational Modifications

Following it's transcription and translation, the androgen receptor is modified with a number of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation, methylation, acetylation, and SUMOylation. The polyglutamine androgen receptor has been found to have different levels of some these post-translational modifications.[13] Further, altering the levels of certain post-translational modifications of the mutant androgen receptor has altered the degree of toxicity in cellular and animal models, suggesting they may be a target for further research and therapeutic development.[13]

Role of Skeletal Muscle in Disease

Several studies have suggested skeletal muscle plays an important role in the pathophysiology of SBMA in animal models.[29] Mice which express the polyglutamine androgen receptor in all tissues were shown to develop progressive neuromuscular degeneration mimicking SBMA, however, when the mice were genetically manipulated to express the protein in all tissues except skeletal muscle, muscle atrophy, neuromuscular degeneration, and survival were significantly improved.[29] Further, treatment of mouse models of SBMA with antisense oligonucleotides targeting the polyglutamine androgen receptor reduced disease burden when administered subcutaneously though they could not cross the blood brain barrier.[29] However, when administered intrathecally into the CNS, disease was not rescued.[29]

Clinical trials

Leuprorelin

Leuprorelin, a GnRH agonist which blocks the synthesis of testosterone when given continuously, was initially shown to be effective at improving motor function in mouse models of SBMA.[13] A small pilot study was performed in which five SBMA patients were given subcutaneous injections of leuprorelin every four weeks for six months, with serial scrotal skin biopsies performed.[30] Nuclear accumulation of polyglutamine androgen receptor was significantly reduced in patient scrotal biopsies. Additionally, serum CK, a marker of muscle deterioration, and testosterone levels were both reduced in patients receiving leuprorelin.[30] Notably, in this study patients were not randomized to treatment groups or placebo controlled.[30]

A subsequent larger study consisted of fifty SBMA patients randomized to either leuprorelin treatment or placebo. This trial spanned 48 weeks of treatment with treatment occurring every four weeks initially. Following treatment, thirty-four patients had an open-label follow-up spanning an additional ninety-six weeks with treatment continuing every twelve weeks.[13][12] At the forty-eight week mark, there was no significant difference in the ALS functional rating scale, the primary outcome measure of the study, between placebo and leuprorelin treated groups.[30][12] There was improvement in swallowing a barium contrast marker, a secondary endpoint of the study, at forty-eight weeks.[30] Further, there was improvement in the ALS functional rating scale at the 96 and 144 week marks, suggesting a longer period may be needed to see effects of leuprorelin.[30]

A larger, multi-center, placebo-controlled, double blind study was then conducted which contained 199 SBMA patients who were randomized to either placebo or leuprorelin treatment. The study spanned forty-eight weeks with leuprorelin treatment every 12 weeks, with ability to swallow a barium contrast marker as the primary endpoint.[30][13] In this study, there was not a significant difference in barium swallow at forty-eight weeks.[30][12] There was also no difference in other videofluorography measurements, supporting the lack of improvement in swallow function in the treatment group.[30] Other secondary measures, such as number of AR positive scrotal cells and serum CK level were significantly different in the treatment group.[30] Though the primary endpoint of the study did not show an effect of leuprorelin on SBMA patients, a subgroup analysis performed on patients who had symptoms for ten years or less did show improved swallowing function, and it was suggested that treatment may be more effective in patients who have shown symptoms for shorter periods of time or with less advanced disease.[30]

A recent follow-up open-label study compared thirty-six patients treated with leuprorelin to nontreated controls over eighty four months, and found that the treated group showed slower decline in motor function than the non-treated group.[13] Significantly differing endpoints of this study included the ALS Functional Rating Scale, the Limb Norris Score, and the Norris Bulbar Score.[13]

Dutasteride

Dutasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor which blocks the conversion of testosterone into dihydrotestosterone. Dihydrotestosterone binds to androgen receptor more avidly, and inhibiting conversion of testosterone into dihydrotestosterone reduces overall androgen receptor activation. Fifty patients were recruited to a randomized, placebo controlled trial spanning two years, with a primary endpoint of quantitative muscle assessment.[30] No significant difference was found in quantitative muscle assessment between the placebo and dutasteride groups at the two year mark.[30] Secondary outcomes including barium swallow and manual muscle testing also showed no significant difference between groups.[13]

Exercise

A small pilot study was performed on eight SBMA patients evaluating the effects of exercise.[30][31] Patients performed thirty minute training sessions on a stationary bicycle with increasing frequency per week (two sessions per week in weeks 1–2, three sessions per week in weeks 3–4, and five sessions per week for weeks 5–12).[30] No significant changes in the primary endpoint VO2max, the maximum oxygen uptake which is a marker of endurance and fitness, were found following the exercise regimen.[30]

A larger study was conducted in 2015 including 50 SBMA patients randomized to exercise or a stretching-only program for twelve weeks.[13][31] The adult myopathy assessment tool was used as the primary endpoint of the study.[13] Secondary endpoints included muscle strength, quality of life score, balance, and IGF-1 levels.[13] No significant differences were found between the primary endpoint or secondary endpoints of the study.[30] However, subgroup analysis did show benefit for low-functioning groups, suggesting there may be a role for exercise in these patients.[13]

BVS857

IGF-1, a signaling molecule downstream of growth hormone, has well established functions promoting skeletal muscle growth.[13] In preclinical studies on mouse models of ALS, IGF-1 was shown to be protective against motor neuron death.[13] A double blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was performed with eighteen SBMA patients receiving BVS857, a mimetic of IGF-1, with nine placebo controls.[13] The study found increased thigh muscle volume improved lean body mass following 12 weeks of treatment in the BVS857 group compared to placebo.[13] However, eleven of eighteen patients were found to have an immune response against BVS857, with five patients developing neutralizing antibodies, posing a challenge for long-term treatment.[13]

See also

References

- ^ Arvin, Shelley (2013-04-01). "Analysis of inconsistencies in terminology of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy and its effect on retrieval of research". Journal of the Medical Library Association. 101 (2): 147–150. doi:10.3163/1536-5050.101.2.010. ISSN 1536-5050. PMC 3634378. PMID 23646030.

- ^ "Kennedy disease | Disease | Overview | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ "Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Genetics Home Reference. 2016-03-21. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

genewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b Kennedy, W. R.; Alter, M.; Sung, J. H. (1968). "Progressive proximal spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy of late onset. A sex-linked recessive trait". Neurology. 18 (7): 671–680. doi:10.1212/WNL.18.7.671. PMID 4233749. S2CID 45735233.

- ^ a b c d A, La Spada (1993–2020). "Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy" (Document).

{{cite document}}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|pmid=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Krivickas, L. S. (2003). "Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and other motor neuron diseases". Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Clinics of North America. 14 (2): 327–345. doi:10.1016/S1047-9651(02)00119-5. PMID 12795519.

- ^ Chen CJ, Fischbeck KH (2006). "Ch. 13: Clinical aspects and the genetic and molecular biology of Kennedy's disease". In Tetsuo Ashizawa, Wells, Robert V. (eds.). Genetic Instabilities and Neurological Diseases (2nd ed.). Boston: Academic Press. pp. 211–222. ISBN 978-0-12-369462-1.

- ^ Browne SE, Beal MF (Mar 2004). "The energetics of Huntington's disease". Neurochem Res (Review). 29 (3): 531–46. doi:10.1023/b:nere.0000014824.04728.dd. PMID 15038601. S2CID 20202258.

- ^ a b c Laskaratos, Achilleas; Breza, Marianthi; Karadima, Georgia; Koutsis, Georgios (2020-06-22). "Wide range of reduced penetrance alleles in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: a model-based approach". Journal of Medical Genetics. 58 (6): jmedgenet–2020–106963. doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2020-106963. ISSN 0022-2593. PMID 32571900. S2CID 219991108.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Pradat, Pierre-François; Bernard, Emilien; Corcia, Philippe; Couratier, Philippe; Jublanc, Christel; Querin, Giorgia; Morélot Panzini, Capucine; Salachas, François; Vial, Christophe; Wahbi, Karim; Bede, Peter; Desnuelle, Claude (2020-04-10). "The French national protocol for Kennedy's disease (SBMA): consensus diagnostic and management recommendations". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 15 (1). doi:10.1186/s13023-020-01366-z. ISSN 1750-1172.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f Hashizume, Atsushi; Fischbeck, Kenneth H.; Pennuto, Maria; Fratta, Pietro; Katsuno, Masahisa (October 2020). "Disease mechanism, biomarker and therapeutics for spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA)". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 91 (10): 1085–1091. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2020-322949. hdl:11577/3398206. ISSN 1468-330X. PMID 32934110. S2CID 221667439.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Arnold, Frederick J.; Merry, Diane E. (October 2019). "Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutics for SBMA/Kennedy's Disease". Neurotherapeutics. 16 (4): 928–947. doi:10.1007/s13311-019-00790-9. ISSN 1878-7479. PMC 6985201. PMID 31686397.

- ^ Fernández-Rhodes, Lindsay E; Kokkinis, Angela D; White, Michelle J; Watts, Charlotte A; Auh, Sungyoung; Jeffries, Neal O; Shrader, Joseph A; Lehky, Tanya J; Li, Li; Ryder, Jennifer E; Levy, Ellen W; Solomon, Beth I; Harris-Love, Michael O; La Pean, Alison; Schindler, Alice B (2011-02-01). "Efficacy and safety of dutasteride in patients with spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: a randomised placebo-controlled trial". The Lancet Neurology. 10 (2): 140–147. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70321-5. ISSN 1474-4422.

- ^ a b "Kennedy's Disease Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". NIH. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- ^ Marcato, S.; Kleinbub, J. R.; Querin, G.; Pick, E.; Martinelli, I.; Bertolin, C.; Cipolletta, S.; Pegoraro, E.; Sorarù, G.; Palmieri, A. (2018-09-11). "Unimpaired Neuropsychological Performance and Enhanced Memory Recall in Patients with Sbma: A Large Sample Comparative Study". Scientific Reports. 8 (1). doi:10.1038/s41598-018-32062-5. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ a b Dejager, S. (2002-08-01). "A Comprehensive Endocrine Description of Kennedy's Disease Revealing Androgen Insensitivity Linked to CAG Repeat Length". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 87 (8): 3893–3901. doi:10.1210/jc.87.8.3893. ISSN 0021-972X.

- ^ Guber, Robert D.; Takyar, Varun; Kokkinis, Angela; Fox, Derrick A.; Alao, Hawwa; Kats, Ilona; Bakar, Dara; Remaley, Alan T.; Hewitt, Stephen M.; Kleiner, David E.; Liu, Chia-Ying; Hadigan, Colleen; Fischbeck, Kenneth H.; Rotman, Yaron; Grunseich, Christopher (2017-12-12). "Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Neurology. 89 (24): 2481–2490. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004748. ISSN 0028-3878. PMID 29142082.

- ^ Lund, A.; Udd, B.; Juvonen, V.; Andersen, P. M.; Cederquist, K.; Davis, M.; Gellera, C.; Kölmel, C.; Ronnevi, L. O.; Sperfeld, A. D.; Sörensen, S. A. (June 2001). "Multiple founder effects in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA, Kennedy disease) around the world". European Journal of Human Genetics. 9 (6): 431–436. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200656. ISSN 1018-4813. PMID 11436124. S2CID 24766290.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lieberman, Andrew P. (2018). "Spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 148: 625–632. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-64076-5.00040-5. ISBN 9780444640765. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 29478604.

- ^ a b Breza, Marianthi; Koutsis, Georgios (March 2019). "Kennedy's disease (spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy): a clinically oriented review of a rare disease". Journal of Neurology. 266 (3): 565–573. doi:10.1007/s00415-018-8968-7. ISSN 1432-1459. PMID 30006721. S2CID 49722696.

- ^ a b Bunting, Emma L.; Hamilton, Joseph; Tabrizi, Sarah J. (2021-09-03). "Polyglutamine diseases". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 72: 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2021.07.001. ISSN 1873-6882. PMID 34488036. S2CID 237407161.

- ^ Adachi, H.; Waza, M.; Katsuno, M.; Tanaka, F.; Doyu, M.; Sobue, G. (2007-04-01). "Pathogenesis and molecular targeted therapy of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology. 33 (2): 135–151. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2990.2007.00830.x. ISSN 1365-2990. PMID 17359355. S2CID 73301743.

- ^ Pennuto, Maria; Rinaldi, Carlo (2018-04-15). "From gene to therapy in spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy: Are we there yet?". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 465: 113–121. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2017.07.005. ISSN 1872-8057. PMID 28688959. S2CID 3915823.

- ^ Atsuta, Naoki (2006). "Natural history of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA): a study of 223 Japanese patients". Brain. 129 (6): 1446–1455. doi:10.1093/brain/awl096. PMID 16621916.

- ^ a b c Katsuno, Masahisa; Tanaka, Fumiaki; Adachi, Hiroaki; Banno, Haruhiko; Suzuki, Keisuke; Watanabe, Hirohisa; Sobue, Gen (December 2012). "Pathogenesis and therapy of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy (SBMA)". Progress in Neurobiology. 99 (3): 246–256. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2012.05.007. ISSN 1873-5118. PMID 22609045. S2CID 207406950.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

emedwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Merry, D. E. (2005). "Animal Models of Kennedy Disease". NeuroRx. 2 (3): 471–479. doi:10.1602/neurorx.2.3.471. PMC 1144490. PMID 16389310.

- ^ a b c d e f Giorgetti, Elisa; Lieberman, Andrew P. (November 2016). "Polyglutamine androgen receptor-mediated neuromuscular disease". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 73 (21): 3991–3999. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2275-1. ISSN 1420-9071. PMC 5045769. PMID 27188284.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Weydt, Patrick; Sagnelli, Anna; Rosenbohm, Angela; Fratta, Pietro; Pradat, Pierre-François; Ludolph, Albert C.; Pareyson, Davide (March 2016). "Clinical Trials in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy-Past, Present, and Future". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience. 58 (3): 379–387. doi:10.1007/s12031-015-0682-7. ISSN 1559-1166. PMID 26572537. S2CID 17956032.

- ^ a b Dahlqvist, Julia Rebecka; Vissing, John (March 2016). "Exercise Therapy in Spinobulbar Muscular Atrophy and Other Neuromuscular Disorders". Journal of Molecular Neuroscience: MN. 58 (3): 388–393. doi:10.1007/s12031-015-0686-3. ISSN 1559-1166. PMID 26585990. S2CID 17216531.

Further reading

- Manzano, Raquel; Sorarú, Gianni; Grunseich, Christopher; Fratta, Pietro; Zuccaro, Emanuela; Pennuto, Maria; Rinaldi, Carlo (2018). "Beyond motor neurons: expanding the clinical spectrum in Kennedy's disease". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 89 (8): 808–812. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2017-316961. ISSN 0022-3050. PMC 6204939. PMID 29353237.

- "Study of Hepatic Function in Patients With Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". clinicaltrials.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- Chedrese, P. Jorge (2009-06-13). Reproductive Endocrinology: A Molecular Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9780387881867.

- Rhodes, Lindsay E.; Freeman, Brandi K.; Auh, Sungyoung; Kokkinis, Angela D.; Pean, Alison La; Chen, Cheunju; Lehky, Tanya J.; Shrader, Joseph A.; Levy, Ellen W. (2009-12-01). "Clinical features of spinal and bulbar muscular atrophy". Brain. 132 (12): 3242–3251. doi:10.1093/brain/awp258. ISSN 0006-8950. PMC 2792370. PMID 19846582.