Léon Blum: Difference between revisions

A.S. Brown (talk | contribs) |

A.S. Brown (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 268: | Line 268: | ||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

* ALQasear, Hussein Muhsin Hashim, and Azhar Kadhim Hasan. "The most important obstacles that led to the fall of the first Leon Blum government, 1937." ''Al-Qadisiyah Journal For Humanities Sciences'' 23.2 (2020): 264–285. [http://qu.edu.iq/journalart/index.php/QJHS/article/download/297/164/ online] |

* ALQasear, Hussein Muhsin Hashim, and Azhar Kadhim Hasan. "The most important obstacles that led to the fall of the first Leon Blum government, 1937." ''Al-Qadisiyah Journal For Humanities Sciences'' 23.2 (2020): 264–285. [http://qu.edu.iq/journalart/index.php/QJHS/article/download/297/164/ online] |

||

*{{cite book |last1=Adamthwaite |first1=Anthony |title=France and the Coming of the Second World War, 1936-1939 |date=1977 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |location=London |isbn=9781000352788}} |

|||

* {{cite journal | last1 = Auboin | first1 = Roger | year = 1937 | title = The Blum Experiment | journal = International Affairs | volume = 16 | issue = 4| pages = 499–517 | doi = 10.2307/2602825 | jstor = 2602825 }} |

* {{cite journal | last1 = Auboin | first1 = Roger | year = 1937 | title = The Blum Experiment | journal = International Affairs | volume = 16 | issue = 4| pages = 499–517 | doi = 10.2307/2602825 | jstor = 2602825 }} |

||

* {{cite book|author=Birnbaum, Pierre |title=Léon Blum: Prime Minister, Socialist, Zionist|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XzDCCAAAQBAJ|year=2015|publisher=Yale UP|page=74|isbn=9780300213737}}, new scholarly biography; [https://www.amazon.com/Leon-Blum-Jewish-Lives-Birnbaum/dp/B013F4ZQWY/ excerpt]; also see [https://newrepublic.com/article/122419/untold-inner-life-first-politician-embrace-his-jewishnes online review] |

* {{cite book|author=Birnbaum, Pierre |title=Léon Blum: Prime Minister, Socialist, Zionist|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XzDCCAAAQBAJ|year=2015|publisher=Yale UP|page=74|isbn=9780300213737}}, new scholarly biography; [https://www.amazon.com/Leon-Blum-Jewish-Lives-Birnbaum/dp/B013F4ZQWY/ excerpt]; also see [https://newrepublic.com/article/122419/untold-inner-life-first-politician-embrace-his-jewishnes online review] |

||

| Line 274: | Line 275: | ||

* Colton, Joel. "Léon Blum and the French Socialists as a government party." ''Journal of Politics'' 15#4 (1953): 517–543. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2126539 in JSTOR] |

* Colton, Joel. "Léon Blum and the French Socialists as a government party." ''Journal of Politics'' 15#4 (1953): 517–543. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/2126539 in JSTOR] |

||

* Colton, Joel. "Politics and Economics in the 1930s: The Balance Sheets of the 'Blum New Deal'." in ''From the Ancien Regime to the Popular Front,'' edited by Charles K. Warner (1969), pp. 181–208. |

* Colton, Joel. "Politics and Economics in the 1930s: The Balance Sheets of the 'Blum New Deal'." in ''From the Ancien Regime to the Popular Front,'' edited by Charles K. Warner (1969), pp. 181–208. |

||

*{{cite book |last1=Crozier |first1=Andrew J. |title=Appeasement And Germany's Last Bid For Colonies |date=1988 |publisher=Macmillan |location=London |isbn=9781349192557}} |

|||

* Dalby, Louise Elliott. ''Leon Blum: Evolution of a Socialist'' (1963) [https://www.questia.com/library/1257485/leon-blum-evolution-of-a-socialist online] |

* Dalby, Louise Elliott. ''Leon Blum: Evolution of a Socialist'' (1963) [https://www.questia.com/library/1257485/leon-blum-evolution-of-a-socialist online] |

||

* Halperin, S. William. "Léon Blum and contemporary French socialism." ''Journal of Modern History'' (1946): 241–250. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1906208 in JSTOR] |

* Halperin, S. William. "Léon Blum and contemporary French socialism." ''Journal of Modern History'' (1946): 241–250. [https://www.jstor.org/stable/1906208 in JSTOR] |

||

Revision as of 04:55, 22 May 2023

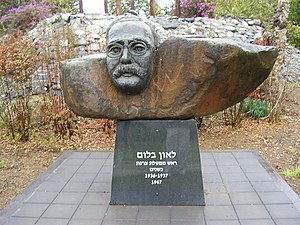

Léon Blum | |

|---|---|

Blum in 1936 | |

| Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 16 December 1946 – 22 January 1947 | |

| President | Vincent Auriol |

| Preceded by | Georges Bidault |

| Succeeded by | Paul Ramadier |

| In office 13 March 1938 – 10 April 1938 | |

| President | Albert Lebrun |

| Deputy | Édouard Daladier |

| Preceded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Succeeded by | Édouard Daladier |

| In office 4 June 1936 – 22 June 1937 | |

| President | Albert Lebrun |

| Deputy | Édouard Daladier |

| Preceded by | Albert Sarraut |

| Succeeded by | Camille Chautemps |

| Deputy Prime Minister of France | |

| In office 28 July 1948 – 5 September 1948 | |

| Prime Minister | André Marie |

| Preceded by | Vacant |

| Succeeded by | André Marie |

| In office 29 June 1937 – 18 January 1938 | |

| Prime Minister | Camille Chautemps |

| Preceded by | Édouard Daladier |

| Succeeded by | Édouard Daladier |

| Personal details | |

| Born | André Léon Blum 9 April 1872 2nd arrondissement of Paris, France |

| Died | 30 March 1950 (aged 77) Jouy-en-Josas, France |

| Political party | French Section of the Workers' International |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | Robert Blum |

| Parents |

|

| Education | University of Paris |

| Signature | |

André Léon Blum (French: [ɑ̃dʁe leɔ̃ blum];[1] 9 April 1872 – 30 March 1950) was a French socialist politician and three-time Prime Minister of France.

As a Jew, he was heavily influenced by the Dreyfus affair of the late 19th century. He was a disciple of socialist leader Jean Jaurès; after Jaurès's assassination in 1914, he became his successor.

Despite Blum's relatively short tenures, his time in office was very influential: as Prime Minister in the left-wing Popular Front government in 1936–1937, he provided a series of major economic and social reforms. Blum declared neutrality in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) to avoid the civil conflict spilling over into France itself. Once out of office in 1938, he denounced the appeasement of Germany.

When Germany defeated France in 1940, he became a staunch opponent of Vichy France. Tried (but never judged) by the Vichy government on charges of treason, he was imprisoned in the Buchenwald concentration camp. After the war, he resumed a transitional leadership role in French politics, helping to bring about the French Fourth Republic, until his death in 1950.

Early life

Blum was born in 1872 in Paris to a moderately prosperous, middle class, assimilated Jewish family in the mercantile business.[2] His father Abraham, a merchant, was born in Alsace.[citation needed]

Blum entered the École Normale Supérieure in 1890 and excelled there, but he dropped out after a year later entering instead the Faculty of Law.[3] He attended the University of Paris and became both a lawyer and literary critic. Between 1905 and 1907 he wrote Du Mariage a highly controversial (for the period) and much talked about critical essay about traditional marriage as envisioned in the late 19th century with its religious and economic background and strong stress on women remaining virgins until their marriage day.[citation needed]

Blum stated that both men and women should enjoy a period of "polygamic" free sex life in order to experience a more mature and stable relationship during later married life. Unsurprisingly he was targeted by the then-powerful Catholic Church in France, in the wake of the turmoil caused by the separation between church and state implemented by Emile Combes in 1905. Far right and royalist politicians and agitatators, and most preeminently Charles Maurras, were incensed, and pelted mostly anti-semitic insults and public outrage at Blum, famously dubbing him "le pornographe du Conseil d'état" as Blum was by then a counsellor of this institution. Although Blum's views being nowadays accepted and mostly mainstream in many developed countries,[4] the book remained an object of scandal long after WWI and the shift to emancipation of women.

First political experiences

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2015) |

While in his youth an avid reader of the works of the nationalist writer Maurice Barrès, Blum had shown little interest in politics until the Dreyfus Affair of 1894, which had a traumatic effect on him as it did on many French Jews.[5] Blum first became personally involved in the Affair when he aided the defense case of Émile Zola in 1898 as a jurist, before which he had not demonstrated interest in public affairs.[3] Campaigning as a Dreyfusard brought him into contact with the socialist leader Jean Jaurès, whom he greatly admired. He began contributing to the socialist daily, L'Humanité, and joined the French Section of the Workers' International (French: Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO). Soon he was the party's main theoretician.[6] It is possible that Blum's interest in politics began somewhat earlier, as Fernand Gregh mentioned in his personal memoirs that Blum had expressed interest in politics as early as 1892.[3]

In July 1914, just as the First World War broke out, Jaurès was assassinated, and Blum became more active in the Socialist party leadership. In August 1914 Blum became assistant to the Socialist Minister of Public Works Marcel Sembat. In 1919 he was chosen as chair of the party's executive committee, and was also elected to the National Assembly as a representative of Paris. Believing that there was no such thing as a "good dictatorship", he opposed participation in the Comintern. Therefore, in 1920, he worked to prevent a split between supporters and opponents of the Russian Revolution, but the radicals seceded, taking L'Humanité with them, and formed the SFIC.

Blum led the SFIO through the 1920s and 1930s, and was also editor of the party's newspaper, Le Populaire.

Popular Front government of 1936–1940

Blum was elected as Deputy for Narbonne in 1929, and was re-elected in 1932 and 1936. In 1933, he expelled Marcel Déat, Pierre Renaudel, and other neosocialists from the SFIO. Political circumstances changed in 1934, when the rise of German dictator Adolf Hitler and fascist riots in Paris caused Stalin and the French Communists to change their policy. In 1935 all the parties of left and centre formed the Popular Front. France had not successfully recovered from the worldwide economic depression, wages had fallen and the working class demanded reforms. The Popular Front won a sweeping victory in June 1936. The Popular Front won a solid majority with 386 seats out of 608. For the first time, the Socialists won more seats than the Radicals; they formed an effective coalition. As Socialist leader Blum became Prime Minister of France and the first socialist to hold that office, he formed a cabinet that included 20 Socialists, 13 Radicals and two Socialist Republicans. The Communists won 15 percent of the vote, and 12 percent of the seats. They supported the government, although they refused to take any cabinet positions. For the first time, the cabinet included three women in minor roles, even though women were not able to vote.[7][8][9]

Labour policies

The election of the left-wing government brought a wave of strikes, involving two million workers, and the seizure of many factories. The strikes were spontaneous and unorganised, but nevertheless the business community panicked and met secretly with Blum, who negotiated a series of reforms, and then gave labour unions the credit for the Matignon Accords.[10] The new laws:

- gave workers the right to strike

- initiated collective bargaining

- legislated the mandating of 12 days of paid annual leave

- legislated a 40-hour working week (outside of overtime)

- raised wages (15% for the lowest-paid workers, and 7% for the relatively well-paid)

- stipulated that employers would recognise shop stewards.

- ensured that there would be no retaliation against strikers.

The government legislated its promised reforms as rapidly as possible. On 11 June, the Chamber of Deputies voted for the forty-hour workweek, the restoration of civil servants' salaries, and two weeks' paid holidays, by a majority of 528 to 7. The Senate voted in favour of these laws within a week.[11]

Blum persuaded the workers to accept pay raises and go back to work. Wages increased sharply; in two years the national average was up 48 percent. However inflation also rose 46%. The imposition of the 40-hour week proved highly inefficient, as industry had a difficult time adjusting to it.[12] The economic confusion hindered the rearmament effort, and the rapid growth of German armaments alarmed Blum. He launched a major program to speed up arms production. The cost forced the abandonment of the social reform programmes that the Popular Front had counted heavily on.[13]

Additional reforms

By mid-August 1936, the parliament had voted for:

- the creation of a national Office du blé (Grain Board or Wheat Office, through which the government helped to market agricultural produce at fair prices for farmers) to stabilise prices and curb speculation

- the nationalisation of the arms industries

- loans to small and medium-sized industries

- the raising of the compulsory school-attendance age to 14 years

- a major public works programme

It also raised the pay, pensions, and allowances of public-sector workers and ex-servicemen. The 1920 Sales Tax, opposed by the Left as a tax on consumers, was abolished and replaced by a production tax, which was considered to be a tax on the producer instead of the consumer.

Blum dissolved the far-right fascist leagues. In turn the Popular Front was actively fought by right-wing and far-right movements, which often used antisemitic slurs against Blum and other Jewish ministers. The Cagoule far-right group even staged bombings to disrupt the government.

Foreign Policy

Shortly after his election, Blum together with his entire cabinet visited the German embassy to meet the new German ambassador, Count Johannes von Welczeck, to tell him that France wanted good relations with Germany and that his government intended to return to the "Locarno era" of the 1920s (i.e friendship with Germany).[14] German propaganda constantly stressed that one of the many alleged "injustices" of the Treaty of Versailles was the loss of Germany's African colonies and demanded that all of the former African colonies "go home to the Reich". Blum believed that the colonial question was the principle problem in Franco-German relations and that there was a "moderate" faction within the German government led by the Reichsbank president Dr. Hjalmar Schacht who were both willing and able to restrain Adolf Hitler.[15] In August 1936, Schacht visited Paris where he met Blum to discuss a possible deal under which France would return the former German African colonies administered by France as mandates for the League of Nations and the end of the trade wars in Europe in exchange for Germany cutting back dramatically its level of military spending.[15] Blum told Schacht that he was willing to return French Togoland (modern Togo) and French Cameroon (modern Cameroon) to Germany as the price of peace, and pursued this line of negotiation with Schacht well into 1937.[16]

Schacht held less power in Berlin than what Blum believed he possessed, but he gave Blum the impression that he was more powerful than what he really was and that the key to preventing world war was the restoration of the German colonial empire in Africa.[15] At the time, Schacht was losing a power struggle over the control of German economic policy to the other Nazi leaders and he was keen for a foreign policy success such as the restoration of Germany's former African colonies that might restore his prestige with Hitler.[15] Blum had good relations with both Welczeck and Schacht whom he viewed as "rational, civilized Europeans" whom it was possible for him to negotiate with.[17] Notably, Hitler refused to see Blum under any conditions and Welczeck was Blum's main conduit with the Reich government.[18] In September 1936, Hitler at the Nuremberg Party Rally launched the Four Year Plan to have the German economy ready for a "total war" by September 1940, which greatly alarmed Blum.[19]

In December 1936, the French Foreign Minister Yvon Delbos contracted Welczeck with an offer for joint Franco-German mediation to end the Spanish Civil War.[19] Provided that the Spanish Civil War could be ended, Delbos was willing to begin talks on the return of the former German colonies plus agreements to end the arms race and the trade wars in Europe.[19] In exchange, Delbos wanted an end to the Four Year Plan.[19] On 18 December 1936, Blum met Welczeck to tell him that the entire cabinet had approved of the offer, saying this was the best chance to save the peace in Europe.[20] Welczeck was personally in favor of accepting Blum's offer, but the German Foreign Minister, Baron Konstantin von Neurath was opposed and persuaded Hitler to reject the offer.[21]

Despite the rejection of the offer, Blum's continuing talks with Dr. Schacht into 1937 led to concerns within the cabinet of Neville Chamberlain that if France returned Togoland and Cameroon to Germany, Britain would come under pressure to return Tanganyika (modern Tanzania) to Germany.[22] The Chamberlain cabinet expressed concern over the fact that Blum had made an offer to return Togoland and Cameroon to Germany, which was felt to have weaken Britain's case for hanging onto Tanganyika.[22] The American historian Gerhard Weinberg wrote both the governments of Blum and Chamberlain were serious about returning the former German African colonies in some form by 1937 as he noted there was a consensus that "...the price-as perceived from London and Paris if not from Douala and Lomé-would be worth paying".[23] However, Hitler wanted the return of the former African colonies without the conditions that Blum and Chamberlain wanted such as a reductions in military spending and the end of the Four Year Plan.

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936 and deeply divided France. Blum adopted a policy of neutrality rather than assisting his ideological fellows, the Spanish Left-leaning Republicans. He acted from fear of splitting his domestic alliance with the centrist Radicals, or even precipitating an ideological civil war inside France. His refusal to send arms to Spain strained his alliance with the Communists, who followed Soviet policy and demanded all-out support for the Spanish Republic. The impossible dilemma caused by this issue led Blum to resign in June 1937.[24] All the constituents of the French left supported the Republican government in Madrid, while the right supported the Nationalist insurgents. Blum's cabinet was deeply divided and he decided on a policy of non-intervention, and collaborated with Britain and 25 other countries to formalize an agreement against sending any munitions or volunteer soldiers to Spain. The Air Minister defied the cabinet and secretly sold warplanes to Madrid. Jackson concludes that the French government "was virtually paralyzed by the menace of civil war at home, the German danger abroad, and the weakness of her own defenses."[25] The Republicans by 1938 were losing badly (they gave up in 1939), sending upwards of 500,000 political refugees across the border into France, where they were held in camps.[26]

Attacks on Blum

On 13 February 1936, shortly before becoming Prime Minister, Blum was dragged from a car and almost beaten to death by the Camelots du Roi, a group of antisemites and royalists. The group's parent organisation, the right-wing Action Française league, was dissolved by the government following this incident, not long before the elections that brought Blum to power.[27] Blum became the first socialist and the first Jew to serve as Prime Minister of France. As such he was an object of particular hatred from antisemitic elements.[28]

In its short life, the Popular Front government passed important legislation, including the 40-hour week, 12 paid annual holidays for the workers, collective bargaining on wage claims, and the full nationalisation of the armament and military aviation industries. This latter sweeping action had the unanticipated effect of disrupting the production of armaments at the wrong time, only three years away from the beginning of war in September 1939. Blum also attempted to pass legislation extending the rights of the Arab population of Algeria, but this was blocked by "colons", colonist representatives in the Chamber and Senate.[29]

Second government in 1938 and collapse

Blum was briefly Prime Minister again in March and April 1938, long enough to ship heavy artillery and other much needed military equipment to the Spanish Republicans.[30] He was unable to establish a stable ministry; on 10 April 1938, his socialist government fell and he was removed from office. In foreign policy, his government was torn between the traditional anti-militarism of the French Left and the urgency of the rising threat of Nazi Germany.

Many historians judge the Popular Front a failure in terms of economics, foreign policy, and long-term stability. "Disappointment and failure," says Jackson, "was the legacy of the Popular Front."[31][32] There is general agreement that at first it created enormous excitement and expectation on the left, but in the end it failed to live up to its promise.[33]

The Daladier era

The new government led by Édouard Daladier cooperated with Britain. During the Sudetenland crisis of 1938, Daladier accepted the offer of the British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to serve as a "honest broker" in an attempt to find a compromise. Chamberlain met with Adolf Hitler at a summit at Berchtesgaden where he agreed that the Sudetenland region of Czechoslovakia would be transferred to Germany.[34] At a subsequent Anglo-German summit at Bad Godesberg, Hitler rejected Chamberlain's plan over a secondary issue as he demanded that the Sudetenland be transferred to Germany before 1 October 1938 while the Anglo-French plan called for a transfer to occur after 1 October.[35] For a time in September 1938, it appeared that Europe was on brink of a war again.[36] The fact that that issue at stake was only a secondary issue, namely the timetable for transferring the Sudetenland, after the primary issue had been settled struck many as bizarre.

When Blum learned on 28 September that an emergency summit would be held in Munich the next day to resolve the crisis, he wrote that felt "an immense response of joy and hope".[37] On 29 September, Blum wrote in an editorial in Le Popularie newspaper: " The Munich meeting is an armful of tinder thrown on a sacred flame at the very moment the flame was flicking and threatening to go out".[35] The Munich Agreement that ended the crisis was a compromise as it was affirmed that the Sudetenland would be transferred to Germany but after only 1 October, albeit on a schedule that favored the German demand to have the Sudetenland "go home to the Reich" as soon as possible. When the Munich Agreement was signed on 30 September 1938, Blum wrote that he felt "soulagement honteux" ("shameful relief") as he wrote that he was happy that France would not be going to war with Germany, but he felt ashamed of an agreement that favored Germany at the expense of Czechoslovakia.[35] On 1 October 1938, Blue wrote in Le Popularie: "There is not a woman and a man to refuse MM. Neville Chamberlain and Édouard Daladier their rightful tribute of gratitude. War is avoided. The scourge recedes. Life can become natural again. One can resume one's work and sleep again. One can enjoy the beauty of an autumn sun. How would it be possible for me not to understand this sense of deliverance when I feel it myself".[35]

During the Danzig crisis of 1939, Blum supported the measures taken by Britain and France to "contain" Germany and deter the Reich from invading Poland.[38] Blum spoke in favor of greater military spending as he noted in an editorial in Le Popularie on 1 April 1939: "This is the state which the dictators have led Europe. For us Socialists, for us pacifists, the appeal to force is today the appeal for peace".[39] When U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued a public letter to Hitler on 14 April 1939, asking him to promise to not threaten his neighbors, Blum expressed hope that this might be a solution for the crisis.[39] However, in a brutal speech to the Reichstag on 28 April 1939, Hitler publicly mocked Roosevelt's appeal. Blum's support for Roosevelt's letter was the only time in the crisis that he expressed support for a measure of reconciliation with Germany..[39]

During the crisis, Blum was greatly alarmed at the attitude of the British Labour Party, which were stoutly opposed to peacetime conscription,[38] The Labour Party were planning make the prospect of peacetime conscription into an election issue (a general election was expected in Britain in 1939 or 1940), which the Chamberlain government gave as the major reason for opposing peacetime conscription. Blum wrote to several Labour leaders as one Socialist to another, urging that Labour support peacetime conscription as necessary to resist Germany.[38] Blum argued that France needed the "continental commitment" from Britain (i.e send a large expeditionary force to France), which in turn required peacetime conscription as the current system of an all-volunteer army would never suffice for the "continental commitment". Blum stated in a public letter to the Labour Party in Le Popularie on 27 April 1939 that he did not like the Chamberlain government, but on the issue of peacetime conscription: "I do not hesitate to state to my Labour comrades my deepest conviction that at very moment at which I write, conscription in England is one of the capital acts upon which the peace of the world depends".[39]

Blum supported the plans for a "peace front" to unite Britain, France and the Soviet Union with the aim of deterring Germany from invading Poland.[40] Knowing that the major issue that was blocking the "peace front" talks were the demand by the Soviet Foreign Commissar Vyacheslav Molotov for the Red Army to have transit rights into Poland in the event of a German invasion, which the Polish Foreign Minister Colonel Józef Beck was utterly opposed to granting, Blum expressed much anger in his editorials as he wrote in an editorial on 25 June 1939 there was "not a day, not a hour to lose" as he urged Beck to concede on the transit rights issue.[41] On 22 August 1939, Blum expressed hope in an editorial in Le Popularie that the "clouds of pessimism" would soon disappear as he asserted that the "peace front" would soon be in existence, which would in turn would deter the Reich from invading Poland.[42] The next day, the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was signed in Moscow. On 24 August 1939, Blum wrote in an editorial that the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact was "a truly extraordinary event, almost incredible, one is dumbfounded by the blow".[41] In his editorial, Blum strongly condemned Joseph Stalin for the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact as he wrote: "One would hardly be able to demonstrate greater audacity, scorn for world opinion and defiance of public morality".[41]

Daladier declared war on Germany when it invaded Poland on 3 September 1939. Eight months of Phoney War thereafter, saw little or no movement. Suddenly in the spring of 1940, the Germans invaded France and defeated the French and British armies in a matter of weeks. The British Expeditionary Force evacuated from Dunkirk, taking many French soldiers along. France gave up, signing an armistice that gave Germany full control over much of France, with a rump Vichy government in control of the remainder as well as of the French colonial empire and the French Navy. The same Parliament that had sponsored the Popular Front program since 1936 remained in power; it voted overwhelmingly to make Marshal Philippe Pétain a dictator and reverse all of the gains of the French Third Republic.

Second World War

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

When the Germans occupied France in June 1940, Blum made no effort to leave the country, despite the extreme danger he was in as a Jew and a socialist leader; instead of fleeing the country, he escaped to southern France, but the French ordered his arrest. Blum was imprisoned in Fort du Portalet in the Pyrenees.[43]

Blum was among "The Vichy 80", a minority of parliamentarians that refused to grant full powers to Marshal Pétain. He was arrested by the authorities in September and held until 1942, when he was put on trial in the Riom Trial on charges of treason, for having "weakened France's defenses" by ordering her arsenal shipped to Spain, leaving France's infantry unsupported by heavy artillery on the eastern front against Nazi Germany. He used the courtroom to make a "brilliant indictment" of the French military and pro-German politicians like Pierre Laval. The trial was such an embarrassment to the Vichy regime that the Germans ordered it called off, worried that Blum's expert performance would have major public consequences.[44][45] He was transferred to German custody and imprisoned in Germany until 1945.

In April 1943, the occupying Government had Blum imprisoned in Buchenwald. As the war worsened for the Germans, they moved him into the section reserved for high-ranking prisoners, hoping that he might be used as a possible hostage for surrender negotiations.[44] His future wife, Jeanne Adèle "Janot" Levylier, chose to come to the camp voluntarily to live with him inside the camp, and they were married there. As the Allied armies approached Buchenwald, he was transferred to Dachau, near Munich, and in late April 1945, together with other notable inmates, to Tyrol. In the last weeks of the war the Nazi regime gave orders that he was to be executed [citation needed], but the local authorities decided not to obey them. Blum was rescued by Allied troops in May 1945. While in prison he wrote his best-known work, the essay À l'échelle humaine ("On a human scale").

His brother René, the founder of the Ballet de l'Opéra à Monte Carlo, was arrested in Paris in 1942. He was deported to Auschwitz, where, according to the Vrba-Wetzler report, he was tortured and killed in September 1942.

Post-war period

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2022) |

After the war, Léon Blum returned to politics, and was again briefly Prime Minister in the transitional postwar coalition government. He advocated an alliance between the center-left and the center-right parties in order to support the Fourth Republic against the Gaullists and the Communists.

Although Blum's last government was very much an interim administration (lasting less than five weeks) it nevertheless succeeded in implementing a number of measures which helped to reduce the cost of living.[46] Blum also served as Vice-Premier for one month in the summer of 1948 in the very short-lived government led by André Marie.

Blum also served as an ambassador on a government loan mission to the United States, and as head of the French mission to UNESCO. He continued to write for Le Populaire until his death at Jouy-en-Josas, near Paris, on 30 March 1950. The kibbutz of Kfar Blum in northern Israel is named after him.

Government

First ministry (4 June 1936 – 22 June 1937)

- Léon Blum – President of the Council

- Édouard Daladier – Vice President of the Council and Minister of National Defense and War

- Yvon Delbos – Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Roger Salengro – Minister of the Interior

- Vincent Auriol – Minister of Finance

- Charles Spinasse – Minister of National Economy

- Jean-Baptiste Lebas – Minister of Labour

- Marc Rucart – Minister of Justice

- Alphonse Gasnier-Duparc – Minister of Marine

- Pierre Cot – Minister of Air

- Jean Zay – Minister of National Education

- Albert Rivière – Minister of Pensions

- Georges Monnet – Minister of Agriculture

- Marius Moutet – Minister of Colonies

- Albert Bedouce – Minister of Public Works

- Henri Sellier – Minister of Public Health

- Robert Jardillier – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

- Paul Bastid – Minister of Commerce

- Camille Chautemps – Minister of State

- Paul Faure – Minister of State

- Maurice Viollette – Minister of State

- Léo Lagrange – Under-Secretary of State for the Organization of the leisure activities and sports -i.e. Minister for the Sports

Changes:

- 18 November 1936 – Marx Dormoy succeeds Roger Salengro as Minister of the Interior, following Salengro's suicide.

Second ministry (13 March – 10 April 1938)

- Léon Blum – President of the Council and Minister of Treasury

- Édouard Daladier – Vice President of the Council and Minister of National Defense and War

- Joseph Paul-Boncour – Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Marx Dormoy – Minister of the Interior

- Charles Spinasse – Minister of Budget

- Albert Sérol – Minister of Labour

- Marc Rucart – Minister of Justice

- César Campinchi – Minister of Military Marine

- Guy La Chambre – Minister of Air

- Jean Zay – Minister of National Education

- Albert Rivière – Minister of Pensions

- Georges Monnet – Minister of Agriculture

- Marius Moutet – Minister of Colonies

- Jules Moch – Minister of Public Works

- Fernand Gentin – Minister of Public Health

- Jean-Baptiste Lebas – Minister of Posts, Telegraphs, and Telephones

- Ludovic-Oscar Frossard – Minister of Propaganda

- Vincent Auriol – Minister of Coordination of Services of the Presidency of the Council

- Pierre Cot – Minister of Commerce

- Paul Faure – Minister of State

- Théodore Steeg – Minister of State

- Maurice Viollette – Minister of State

- Albert Sarraut – Minister of State in charge of North African Affairs

- Léo Lagrange – Under-Secretary of State for the Sports, the Leisure activities and the Physical Education

Third ministry (16 December 1946 – 22 January 1947)

- Léon Blum – President of the Provisional Government and Minister of Foreign Affairs

- André Le Troquer – Minister of National Defense

- Édouard Depreux – Minister of the Interior

- André Philip – Minister of Familial Economy and Finance

- Robert Lacoste – Minister of Industrial Production

- Daniel Mayer – Minister of Labour and Social Security

- Paul Ramadier – Minister of Justice

- Yves Tanguy – Minister of Public Utilities

- Marcel Edmond Naegelen – Minister of National Education

- Max Lejeune – Minister of Veterans and War Victims

- François Tanguy-Prigent – Minister of Agriculture

- Marius Moutet – Minister of Overseas France

- Jules Moch – Minister of Public Works, Transport, Reconstruction, and Town Planning

- Pierre Ségelle – Minister of Public Health and Population

- Eugène Thomas – Minister of Posts

- Félix Gouin – Minister of Planning

- Guy Mollet – Minister of State

- Augustin Laurent – Minister of State

Changes:

- 23 December 1946 – Augustin Laurent succeeds Moutet as Minister of Overseas France.

Books by Léon Blum

- Nouvelles conversations de Goethe avec Eckermann, Éditions de la Revue blanche, 1901.

- Du mariage, Paul Ollendorff, 1907; English translation, Marriage, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1937.

- Stendhal et le beylisme, Paul Ollendorff, 1914.

- Pour être socialiste, Libraire Populaire, 1920.

- Bolchévisme et socialisme, Librairie populaire, 1927.

- Souvenirs sur l'Affaire, Gallimard, 1935.

- La Réforme gouvernementale, Bernard Grasset, 1936.

- À l'échelle humaine, Gallimard, 1945; English translation, For All Mankind, Victor Gollancz, 1946 (Left Book Club).

- L'Histoire jugera, Éditions de l'Arbre, 1943.

- Le Dernier mois, Diderot, 1946.

- Révolution socialiste ou révolution directoriale, J. Lefeuvre, 1947.

- Discours politiques, Imprimerie Nationale, 1997.

References

- ^ Colton, Joel (10 July 2013) [1966]. Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-307-83089-0. LCCN 65-18768. OCLC 265833.

The Blum family has always pronounced its name in a way that indicates its Alsatian origin.

- ^ Responsibility (1998), p. 30: "Léon Blum was born in Paris in 1872, into a moderately successful lower-middle-class commercial family of semiassimilated Jews."

- ^ a b c Responsibility (1998), p. 31.

- ^ "Léon Blum et la question du mariage". LEFIGARO (in French). 28 April 2021. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ Joel Colton, Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics, 1987, 20.

- ^ Joel Colton, Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics, 1987, 20.

- ^ Julian T. Jackson, Popular Front in France: Defending Democracy 1934–1938 (1988)

- ^ Jean Lacouture, Leon Blum (1982) pp. 235–304

- ^ Maurice Larkin, France since the popular front: government and people, 1936–1996 (1997) pp. 45–62

- ^ Adrian Rossiter, "Popular Front economic policy and the Matignon negotiations". Historical Journal 30#3 (1987): 663–684. in JSTOR

- ^ Jackson, Popular Front in France p 288

- ^ Larkin, France since the popular front: government and people, 1936–1996 (1997) pp. 55–57

- ^ Martin Thomas, "French Economic Affairs and Rearmament: The First Crucial Months, June–September 1936". Journal of Contemporary History 27#4 (1992) pp: 659–670 in JSTOR.

- ^ Adamthwaite 1977, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Weinberg 1980, p. 67.

- ^ Weinberg 1980, p. 71.

- ^ Colton 1987, p. 214.

- ^ Colton 1966, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d Weinberg 1980, p. 90.

- ^ Crozier 1988, p. 194.

- ^ Weinberg 1980, p. 90-91.

- ^ a b Weinberg 1980, p. 74.

- ^ Weinberg 1980, p. 75.

- ^ Windell, George C. (1962). "Leon Blum and the Crisis over Spain, 1936". Historian. 24 (4): 423–449. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6563.1962.tb01732.x.

- ^ Gabriel Jackson, The Spanish Republic in the Civil War, 1931–1939 (1965) p 254

- ^ Louis Stein, Beyond Death and Exile: The Spanish Republicans in France, 1939–1955 (1980)

- ^ The Times | UK News, World News and Opinion

- ^ Léon BLUM 1872 – 1950 Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Lazare Landau, Extrait de l'Almanach du KKL-Strasbourg 5753-1993 (avec l'aimable autorisation des Editeurs), at Le judaisme alsacien

- ^ Joel Colton. Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics (1966) p 162.

- ^ Jean Lacouture, Leon Blum (New York, Holmes & Meier, 1982) p. 349.

- ^ Julian Jackson, Popular Front in France: Defending Democracy 1934–1938 (1988), pp 172, 215, 278–87, quotation on page 287.

- ^ Bernard and Dubief (1988). The Decline of the Third Republic, 1914–1938. pp. 328–33. ISBN 9780521358545.

- ^ Wall, Irwin M. (1987). "Teaching the Popular Front". History Teacher. 20 (3): 361–378. doi:10.2307/493125. JSTOR 493125.

- ^ Colton 1966, p. 316.

- ^ a b c d Colton 1966, p. 317.

- ^ Cotton 1987, p. 317.

- ^ Cotton 1966, p. 317.

- ^ a b c Cotton 1966, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d Colton 1966, p. 321.

- ^ Cotton 1966, p. 322.

- ^ a b c Colton 1966, p. 330.

- ^ Colton 1966, p. 322.

- ^ Fort du Portalet Office de tourisme Vallée d'Aspe (www.tourisme-aspe.com)

- ^ a b Responsibility (1998), p. 34.

- ^ An excerpt from Pierre Birnbaum's biography of the French titan

- ^ A History of the Twentieth Century: Volume Two: 1933–1951, by Martin Gilbert

Further reading

- ALQasear, Hussein Muhsin Hashim, and Azhar Kadhim Hasan. "The most important obstacles that led to the fall of the first Leon Blum government, 1937." Al-Qadisiyah Journal For Humanities Sciences 23.2 (2020): 264–285. online

- Adamthwaite, Anthony (1977). France and the Coming of the Second World War, 1936-1939. London: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781000352788.

- Auboin, Roger (1937). "The Blum Experiment". International Affairs. 16 (4): 499–517. doi:10.2307/2602825. JSTOR 2602825.

- Birnbaum, Pierre (2015). Léon Blum: Prime Minister, Socialist, Zionist. Yale UP. p. 74. ISBN 9780300213737., new scholarly biography; excerpt; also see online review

- Codding, George A., and William Safran. Ideology and politics: the Socialist Party of France (Routledge, 2019).

- Colton, Joel (1966). Leon Blum: Humanist in Politics. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-83089-0. LCCN 65-18768. OCLC 265833., older scholarly biography

- Colton, Joel. "Léon Blum and the French Socialists as a government party." Journal of Politics 15#4 (1953): 517–543. in JSTOR

- Colton, Joel. "Politics and Economics in the 1930s: The Balance Sheets of the 'Blum New Deal'." in From the Ancien Regime to the Popular Front, edited by Charles K. Warner (1969), pp. 181–208.

- Crozier, Andrew J. (1988). Appeasement And Germany's Last Bid For Colonies. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9781349192557.

- Dalby, Louise Elliott. Leon Blum: Evolution of a Socialist (1963) online

- Halperin, S. William. "Léon Blum and contemporary French socialism." Journal of Modern History (1946): 241–250. in JSTOR

- Jackson, Julian. The popular Front in France: defending democracy, 1934–38 (Cambridge UP, 1990.)

- Jordan, Nicole. "Léon Blum and Czechoslovakia, 1936–1938." French History 5#1 (1991): 48–73. doi: 10.1093/fh/5.1.48

- Judt, Tony (1998). The burden of responsibility : Blum, Camus, Aron, and the French twentieth century. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226414195.

- Lacouture, Jean. Leon Blum (English edition 1982) online

- Marcus, John T. French Socialism in the Crisis Years, 1933–1936: Fascism and the French Left (1958) online

- Mitzman, Arthur. "The French Working Class and the Blum Government (1936–37)." International Review of Social History 9#3 (1964) pp: 363–390.

- Wall, Irwin M. "The Resignation of the First Popular Front Government of Leon Blum, June 1937." French Historical Studies (1970): 538–554. in JSTOR

- Weinberg, Gerhard (1980). The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Volume 2 Starting World War Two 1937-1939. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

External links

- 1872 births

- 1950 deaths

- 20th-century heads of state of France

- Politicians from Paris

- Jewish French politicians

- 20th-century French Jews

- French Section of the Workers' International politicians

- Heads of state of France

- Prime Ministers of France

- French Foreign Ministers

- French Ministers of Finance

- French socialists

- Members of the 12th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 13th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 14th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 15th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- Members of the 16th Chamber of Deputies of the French Third Republic

- The Vichy 80

- Human Rights League (France) members

- Jewish socialists

- Jewish prime ministers

- Members of the Executive of the Labour and Socialist International

- Lycée Henri-IV alumni

- École Normale Supérieure alumni

- Buchenwald concentration camp survivors

- Dachau concentration camp survivors

- Jewish anti-fascists

- Dreyfusards