Condom: Difference between revisions

Comment out refs & wikilink to section containing cites |

Es uomikim (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

According to a 2000 report by the [[National Institutes of Health]], correct and consistent use of latex condoms reduces the risk of [[HIV]]/[[AIDS]] transmission by approximately 85% relative to risk when unprotected, putting the seroconversion rate (infection rate) at 0.9 per 100 person-years with condom, down from 6.7 per 100 person-years. The same review also found condom use significantly reduces the risk of [[gonorrhea]] for men.<!-- |

According to a 2000 report by the [[National Institutes of Health]], correct and consistent use of latex condoms reduces the risk of [[HIV]]/[[AIDS]] transmission by approximately 85% relative to risk when unprotected, putting the seroconversion rate (infection rate) at 0.9 per 100 person-years with condom, down from 6.7 per 100 person-years. The same review also found condom use significantly reduces the risk of [[gonorrhea]] for men.<!-- |

||

--><ref name="workshop">{{cite conference |last=National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | authorlink = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | coauthors = National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services |title=Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention |pages=pp.13-15 |date=2001-07-20 |location=Hyatt Dulles Airport, Herndon, Virginia |url=http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/about/organization/dmid/PDF/condomReport.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-03-20 }}</ref> |

--><ref name="workshop">{{cite conference |last=National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | authorlink = National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases | coauthors = National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services |title=Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention |pages=pp.13-15 |date=2001-07-20 |location=Hyatt Dulles Airport, Herndon, Virginia |url=http://www3.niaid.nih.gov/about/organization/dmid/PDF/condomReport.pdf |format=PDF |accessdate=2009-03-20 }}</ref> A meta-analysis published in 2007, have shown condoms effectiveness to be approximately 80%.<ref>{{cite paper|author=Cayley, W.E. & Davis-Beaty, K.|year=2007|Effectiveness of Condoms in Reducing Heterosexual Transmission of HIV (Review)|publisher=John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.|url=http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003255/frame.html}}</ref> Other sources estimate their effectiveness to 80-95%.<ref>{{cite book|author=World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR) & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), INFO Project|year=2007|title=Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers| publisher=INFO Project at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health|url=http://www.infoforhealth.org/globalhandbook/index.shtml|pages=200}}</ref> |

||

A 2006 study reports that proper condom use decreases the risk of transmission for [[human papillomavirus]] by approximately 70%.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Winer, R; Hughes, J; Feng, Q; O'Reilly, S; Kiviat, N; Holmes, K; Koutsky, L |title=Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women | doi = 10.1056/NEJMoa053284+|journal=N Engl J Med |volume=354 |issue=25 |pages=2645–54 |year=2006 |pmid=16790697 |url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/354/25/2645 |accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> Another study in the same year found consistent condom use was effective at reducing transmission of [[Herpes simplex virus|herpes simplex virus-2]] also known as genital [[Herpes simplex|herpes]], in both men and women.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Wald |first=Anna | coauthors = DiCarlo, Richard |title=The Relationship between Condom Use and Herpes Simplex Virus Acquisition| journal = Annals of Internal Medicine| volume = 143|pages=707–713|year=2005 |pmid=16287791 | url=http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/143/10/707 |accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> |

A 2006 study reports that proper condom use decreases the risk of transmission for [[human papillomavirus]] by approximately 70%.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Winer, R; Hughes, J; Feng, Q; O'Reilly, S; Kiviat, N; Holmes, K; Koutsky, L |title=Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women | doi = 10.1056/NEJMoa053284+|journal=N Engl J Med |volume=354 |issue=25 |pages=2645–54 |year=2006 |pmid=16790697 |url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/354/25/2645 |accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> Another study in the same year found consistent condom use was effective at reducing transmission of [[Herpes simplex virus|herpes simplex virus-2]] also known as genital [[Herpes simplex|herpes]], in both men and women.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Wald |first=Anna | coauthors = DiCarlo, Richard |title=The Relationship between Condom Use and Herpes Simplex Virus Acquisition| journal = Annals of Internal Medicine| volume = 143|pages=707–713|year=2005 |pmid=16287791 | url=http://www.annals.org/cgi/content/full/143/10/707 |accessdate=2007-04-07}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 20:16, 25 August 2009

| Condom | |

|---|---|

A rolled-up condom | |

| Background | |

| Type | Barrier |

| First use | Ancient Rubber: 1855 Latex: 1920 Polyurethane: 1994 |

| Pregnancy rates (first year, latex) | |

| Perfect use | 2% |

| Typical use | 10–18% |

| Usage | |

| User reminders | Latex condoms damaged by oil-based lubricants |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | Yes |

| Benefits | No medications or clinic visits required |

A condom (Template:Pron-en (US) or /ˈkɒndɒm/ (UK)) is a barrier device most commonly used during sexual intercourse to reduce the likelihood of pregnancy and spreading sexually transmitted diseases (STDs—such as gonorrhea, syphilis, and HIV). It is put on a man's erect penis and physically blocks ejaculated semen from entering the body of a sexual partner. Because condoms are waterproof, elastic, and durable, they are also used in a variety of secondary applications. These include collection of semen for use in infertility treatment as well as non-sexual uses such as creating waterproof microphones and protecting rifle barrels from clogging.

In the modern age, condoms are most often made from latex, but some are made from other materials such as polyurethane, or lamb intestine. A female condom is also available, most often made of polyurethane. As a method of contraception, male condoms have the advantage of being inexpensive, easy to use, having few side effects, and of offering protection against sexually transmitted diseases. With proper knowledge and application technique—and use at every act of intercourse—users of male condoms experience a 2% per-year pregnancy rate.

Condoms have been used for at least 400 years. Since the nineteenth century, they have been one of the most popular methods of contraception in the world. While widely accepted in modern times, condoms have generated some controversy, primarily over what role they should play in sex education classes. Additionally, improper disposal of condoms contributes to litter problems, and the Roman Catholic Church generally opposes condom use.

History

Before the 19th century

Whether condoms were used in ancient civilizations is debated by archaeologists and historians.[1]: 11 In ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome, pregnancy prevention was generally seen as a woman's responsibility, and the only well documented contraception methods were female-controlled devices.[1]: 17, 23 In Asia before the fifteenth century, some use of glans condoms (devices covering only the head of the penis) is recorded. Condoms seem to have been used for contraception, and to have been known only by members of the upper classes. In China, glans condoms may have been made of oiled silk paper, or of lamb intestines. In Japan, they were made of tortoise shell or animal horn.[1]: 60–1

In 16th century Italy, Gabriele Falloppio wrote a treatise on syphilis.[1]: 51, 54–5 The earliest documented strain of syphilis, first appearing in a 1490s outbreak, caused severe symptoms and often death within a few months of contracting the disease.[2][3] Falloppio's treatise is the earliest uncontested description of condom use: it describes linen sheaths soaked in a chemical solution and allowed to dry before use. The cloths he described were sized to cover the glans of the penis, and were held on with a ribbon.[1]: 51, 54–5 [4] Falloppio claimed that an experimental trial of the linen sheath demonstrated protection against syphilis.[5]

After this, the use of penis coverings to protect from disease is described in a wide variety of literature throughout Europe. The first indication that these devices were used for birth control, rather than disease prevention, is the 1605 theological publication De iustitia et iure (On justice and law) by Catholic theologian Leonardus Lessius, who condemned them as immoral.[1]: 56 In 1666, the English Birth Rate Commission attributed a recent downward fertility rate to use of "condons", the first documented use of that word (or any similar spelling).[1]: 66–8

In addition to linen, condoms during the Renaissance were made out of intestines and bladder. In the late 15th century, Dutch traders introduced condoms made from "fine leather" to Japan. Unlike the horn condoms used previously, these leather condoms covered the entire penis.[1]: 61

From at least the 18th century, condom use was opposed in some legal, religious, and medical circles for essentially the same reasons that are given today: condoms reduce the likelihood of pregnancy, which some thought immoral or undesirable for the nation; they do not provide full protection against sexually transmitted infections, while belief in their protective powers was thought to encourage sexual promiscuity; and they are not used consistently due to inconvenience, expense, or loss of sensation.[1]: 73, 86–8, 92

Despite some opposition, the condom market grew rapidly. In the 18th century, condoms were available in a variety of qualities and sizes, made from either linen treated with chemicals, or "skin" (bladder or intestine softened by treatment with sulfur and lye).[1]: 94–5 They were sold at pubs, barbershops, chemist shops, open-air markets, and at the theater throughout Europe and Russia.[1]: 90–2, 97, 104 They later spread to America, although in every place there were generally used only by the middle and upper classes, due to both expense and lack of sex education.[1]: 116–21

1800 through 1920s

The early nineteenth century saw contraceptives promoted to the poorer classes for the first time. Writers on contraception tended to prefer other methods of birth control. Feminists of this time period wanted birth control to be exclusively in the hands of women, and disapproved of male-controlled methods such as the condom.[1]: 129, 152–3 Other writers cited both the expense of condoms and their unreliability (they were often riddled with holes, and often fell off or broke), but they discussed condoms as a good option for some, and as the only contraceptive that also protected from disease.[1]: 88, 90, 125, 129–30

Many countries passed laws impeding the manufacture and promotion of contraceptives.[1]: 144, 163–4, 168–71, 193 In spite of these restrictions, condoms were promoted by traveling lecturers and in newspaper advertisements, using euphemisms in places where such ads were illegal.[1]: 127, 130–2, 138, 146–7 Instructions on how to make condoms at home were distributed in the United States and Europe.[1]: 126, 136 Despite social and legal opposition, at the end of the nineteenth century the condom was the Western world's most popular birth control method.[1]: 173–4

Beginning in the second half of the nineteenth century, American rates of sexually transmitted diseases skyrocketed. Causes cited by historians include effects of the American Civil War, and the ignorance of prevention methods promoted by the Comstock laws.[1]: 137–8, 159 To fight the growing epidemic, sex education classes were introduced to public schools for the first time, teaching about venereal diseases and how they were transmitted. They generally taught that abstinence was the only way to avoid sexually transmitted diseases.[1]: 179–80 Condoms were not promoted for disease prevention because the medical community and moral watchdogs considered STDs to be punishment for sexual misbehavior. The stigma against victims of these diseases was so great that many hospitals refused to treat people who had syphilis.[1]: 176

The German military was the first to promote condom use among its soldiers, beginning in the later 1800s.[1]: 169, 181 Early twentieth century experiments by the American military concluded that providing condoms to soldiers significantly lowered rates of sexually transmitted diseases.[1]: 180–3 During World War I, the United States and (at the beginning of the war only) Britain were the only countries with soldiers in Europe who did not provide condoms and promote their use.[1]: 187–90

In the decades after World War I, there remained social and legal obstacles to condom use throughout the U.S. and Europe.[1]: 208–10 Founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud opposed all methods of birth control on the grounds that their failure rates were too high. Freud was especially opposed to the condom because it cut down on sexual pleasure. Some feminists continued to oppose male-controlled contraceptives such as condoms. In 1920 the Church of England's Lambeth Conference condemned all "unnatural means of conception avoidance." London's Bishop Arthur Winnington-Ingram complained of the huge number of condoms discarded in alleyways and parks, especially after weekends and holidays.[1]: 211–2

However, European militaries continued to provide condoms to their members for disease protection, even in countries where they were illegal for the general population.[1]: 213–4 Through the 1920s, catchy names and slick packaging became an increasingly important marketing technique for many consumer items, including condoms and cigarettes.[1]: 197 Quality testing became more common, involving filling each condom with air followed by one of several methods intended to detect loss of pressure.[1]: 204, 206, 221–2 Worldwide, condom sales doubled in the 1920s.[1]: 210

Rubber and manufacturing advances

The rubber vulcanization process was patented by Charles Goodyear in 1844.[6] The first rubber condom was produced in 1855.[7] For many decades, rubber condoms were manufactured by wrapping strips of raw rubber around penis-shaped molds, then dipping the wrapped molds in a chemical solution to cure the rubber.[1]: 148 In 1912, a German named Julius Fromm developed a new, improved manufacturing technique for condoms: dipping glass molds into a raw rubber solution.[7] Called cement dipping, this method required adding gasoline or benzene to the rubber to make it liquid.[1]: 200 Latex, rubber suspended in water, was invented in 1920. Latex condoms required less labor to produce than cement-dipped rubber condoms, which had to be smoothed by rubbing and trimming. The use of water to suspend the rubber instead of gasoline and benzene eliminated the fire hazard previously associated with all condom factories. Latex condoms also performed better for the consumer: they were stronger and thinner than rubber condoms, and had a shelf life of five years (compared to three months for rubber).[1]: 199–200

Until the twenties, all condoms were individually hand-dipped by semiskilled workers. Throughout the decade of the 1920s, advances in the automation of the condom assembly line were made. The first fully automated line was patented in 1930. Major condom manufacturers bought or leased conveyor systems, and small manufacturers were driven out of business.[1]: 201–3 The skin condom, now significantly more expensive than the latex variety, became restricted to a niche high-end market.[1]: 220

1930 to present

In 1930 the Anglican Church's Lambeth Conference sanctioned the use of birth control by married couples. In 1931 the Federal Council of Churches in the U.S. issued a similar statement.[1]: 227 The Roman Catholic Church responded by issuing the encyclical Casti Connubii affirming its opposition to all contraceptives, a stance it has never reversed.[1]: 228–9

In the 1930s, legal restrictions on condoms began to be relaxed.[8][1]: 216, 226, 234 During this period, two of the few places where condoms became more restricted were Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany (limited sales as disease preventatives were still allowed).[1]: 252, 254–5 During the Depression, condom lines by Schmid gained in popularity. Schmid still used the cement-dipping method of manufacture which had two advantages over the latex variety. Firstly, cement-dipped condoms could be safely used with oil-based lubricants. Secondly, while less comfortable, these older-style rubber condoms could be reused and so were more economical, a valued feature in hard times.[1]: 217–9 More attention was brought to quality issues in the 1930s, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration began to regulate the quality of condoms sold in the United States.[1]: 223–5

Throughout World War II, condoms were not only distributed to male U.S. military members, but also heavily promoted with films, posters, and lectures.[1]: 236–8, 259 European and Asian militaries on both sides of the conflict also provided condoms to their troops throughout the war, even Germany which outlawed all civilian use of condoms in 1941.[1]: 252–4, 257–8 In part because condoms were readily available, soldiers found a number of non-sexual uses for the devices, many of which continue to this day.

After the war, condom sales continued to grow. From 1955–1965, 42% of Americans of reproductive age relied on condoms for birth control. In Britain from 1950–1960, 60% of married couples used condoms. The birth control pill became the world's most popular method of birth control in the years after its 1960 début, but condoms remained a strong second. The U.S. Agency for International Development pushed condom use in developing countries to help solve the "world population crises": by 1970 hundreds of millions of condoms were being used each year in India alone.[1]: 267–9, 272–5 (This number has grown in recent decades: in 2004, the government of India purchased 1.9 billion condoms for distribution at family planning clinics.)[9]

In the 1960s and 1970s quality regulations tightened,[10] and more legal barriers to condom use were removed.[1]: 276–9 In Ireland, legal condom sales were allowed for the first time in 1978.[1]: 329–30 Advertising, however was one area that continued to have legal restrictions. In the late 1950s, the American National Association of Broadcasters banned condom advertisements from national television: this policy remained in place until 1979.[1]: 273–4, 285

After learning in the early 1980s that AIDS can be a sexually transmitted infection,[11] the use of condoms was encouraged to prevent transmission of HIV. Despite opposition by some political, religious, and other figures, national condom promotion campaigns occurred in the U.S. and Europe.[1]: 299, 301, 306–7, 312–8 These campaigns increased condom use significantly.[1]: 309–17

Due to increased demand and greater social acceptance, condoms began to be sold in a wider variety of retail outlets, including in supermarkets and in discount department stores such as Wal-Mart.[1]: 305 Condom sales increased every year until 1994, when media attention to the AIDS pandemic began to decline.[1]: 303–4 The phenomenon of decreasing use of condoms as disease preventatives has been called prevention fatigue or condom fatigue. Observers have cited condom fatigue in both Europe and North America.[12][13] As one response, manufacturers have changed the tone of their advertisements from scary to humorous.[1]: 303–4 New developments continue to occur in the condom market, with the first polyurethane condom—branded Avanti and produced by the manufacturer of Durex—introduced in the 1990s,[1]: 324–5 and the first custom sized-to-fit condom, called TheyFit, introduced in 2003.[14] Worldwide condom use is expected to continue to grow: one study predicted that developing nations would need 18.6 billion condoms in 2015.[1]: 342 Condoms have become an integral part of modern societies.

Etymology and other terms

The term condom first appears in the early 18th century. Its etymology is unknown. In popular tradition, the invention and naming of the condom came to be attributed to an associate of England's King Charles II, one "Dr. Condom" or "Earl of Condom". There is however no evidence of the existence of such a person, and condoms had been used for over one hundred years before King Charles II ascended to the throne.[1]: 54, 68

A variety of Latin etymologies have been proposed, including condon (receptacle),[15] condamina (house),[16] and cumdum (scabbard or case).[1]: 70–1 It has also been speculated to be from the Italian word guantone, derived from guanto, meaning glove.[17] William E. Kruck wrote an article in 1981 concluding that, "As for the word 'condom', I need state only that its origin remains completely unknown, and there ends this search for an etymology."[18] Modern dictionaries may also list the etymology as "unknown".[19]

Other terms are also commonly used to describe condoms. In North America condoms are also commonly known as prophylactics, or rubbers. In Britain they may be called French letters.[20] Additionally, condoms may be referred to using the manufacturer's name.

Varieties

Most condoms have a reservoir tip or teat end, making it easier to accommodate the man's ejaculate. Condoms come in different sizes, from oversized to snug and they also come in a variety of surfaces intended to stimulate the user's partner. Condoms are usually supplied with a lubricant coating to facilitate penetration, while flavored condoms are principally used for oral sex. As mentioned above, most condoms are made of latex, but polyurethane and lambskin condoms are also widely available.

Materials

Natural latex

Latex has outstanding elastic properties: Its tensile strength exceeds 30 MPa, and latex condoms may be stretched in excess of 800% before breaking.[21] In 1990 the ISO set standards for condom production (ISO 4074, Natural latex rubber condoms), and the EU followed suit with its CEN standard (Directive 93/42/EEC concerning medical devices). Every latex condom is tested for holes with an electrical current. If the condom passes, it is rolled and packaged. In addition, a portion of each batch of condoms is subject to water leak and air burst testing.[22]

Latex condoms used with oil-based lubricants such as petroleum jelly are likely to break or slip off due to loss of elasticity caused by the oils.[23]

Synthetic

The most common non-latex condoms are made from polyurethane. Condoms may also be made from other synthetic materials, such as AT-10 resin, and most recently polyisoprene.[24]

Polyurethane condoms tend to be the same width and thickness as latex condoms, with most polyurethane condoms between 0.04 mm and 0.07 mm thick.[25] Polyurethane is also the material of many female condoms.

Polyurethane can be considered better than latex in several ways: it conducts heat better than latex, is not as sensitive to temperature and ultraviolet light (and so has less rigid storage requirements and a longer shelf life), can be used with oil-based lubricants, is less allergenic than latex, and does not have an odor.[26] Polyurethane condoms have gained FDA approval for sale in the United States as an effective method of contraception and HIV prevention, and under laboratory conditions have been shown to be just as effective as latex for these purposes.[27]

However, polyurethane condoms are less elastic than latex ones, and may be more likely to slip or break than latex,[26][28] and are more expensive.

Polyisoprene is a synthetic version of natural rubber latex. While significantly more expensive,[29] it has the advantages of latex (such as being softer and more elastic than polyurethane condoms)[24] without the protein which is responsible for latex allergies.[29]

Lambskin

Condoms made from sheep intestines, labeled "lambskin", are also available. They provide more sensation and are less allergenic than latex. However, there is an increased risk of transmitting STDs compared to latex because of pores in the material, which are thought to be large enough to allow infectious agents to pass through, albeit blocking the passage of sperm.[30] Lambskin condoms are also significantly more expensive than other types.

Spermicidal

Some latex condoms are lubricated at the manufacturer with a small amount of a nonoxynol-9, a spermicidal chemical. According to Consumer Reports, condoms lubricated with spermicide have no additional benefit in preventing pregnancy, have a shorter shelf life, and may cause urinary-tract infections in women.[31] In contrast, application of separately packaged spermicide is believed to increase the contraceptive efficacy of condoms.[32]

Nonoxynol-9 was once believed to offer additional protection against STDs (including HIV) but recent studies have shown that, with frequent use, nonoxynol-9 may increase the risk of HIV transmission.[33] The World Health Organization says that spermicidally lubricated condoms should no longer be promoted. However, it recommends using a nonoxynol-9 lubricated condom over no condom at all.[34] As of 2005, nine condom manufacturers have stopped manufacturing condoms with nonoxynol-9 and Planned Parenthood has discontinued the distribution of condoms so lubricated.[35]

Textured

Textured condoms include studded and ribbed condoms which can provide extra sensations to both partners. The studs or ribs can be located on the inside, outside, or both; alternatively, they are located in specific sections to provide directed stimulation to either the g-spot or perineum. Many textured condoms which advertise "mutual pleasure" also are bulb-shaped at the top, to provide extra stimulation to the male.[36] Studded condoms should be avoided with anal intercourse as they can irritate and possibly tear the walls of the anus. Some women experience irritation during vaginal intercourse with studded condoms.

Other

A female version of the condom has been available since 1988. Female condoms were initially all made of polyurethane, but newer versions may be made of nitrile or latex.[37]

The anti-rape condom is another variation designed to be worn by women. It is designed to cause pain to the attacker, hopefully allowing the victim a chance to escape.[38]

A collection condom is used to collect semen for fertility treatments or sperm analysis. These condoms are designed to maximize sperm life.

Some condom-like devices are intended for entertainment only, such novelty condoms may not provide protection against pregnancy and STDs.[39]

Effectiveness

In preventing pregnancy

The effectiveness of condoms, as of most forms of contraception, can be assessed two ways. Perfect use or method effectiveness rates only include people who use condoms properly and consistently. Actual use, or typical use effectiveness rates are of all condom users, including those who use condoms incorrectly or do not use condoms at every act of intercourse. Rates are generally presented for the first year of use.[40] Most commonly the Pearl Index is used to calculate effectiveness rates, but some studies use decrement tables.[41]: 141

The typical use pregnancy rate among condom users varies depending on the population being studied, ranging from 10–18% per year.[42] The perfect use pregnancy rate of condoms is 2% per year.[40] Condoms may be combined with other forms of contraception (such as spermicide) for greater protection.[32]

In preventing STDs

Condoms are widely recommended for the prevention of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs). They have been shown to be effective in reducing infection rates in both men and women. While not perfect, the condom is effective at reducing the transmission of organisms that cause AIDS, genital herpes, genital warts, syphilis, Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and other diseases.[39]

According to a 2000 report by the National Institutes of Health, correct and consistent use of latex condoms reduces the risk of HIV/AIDS transmission by approximately 85% relative to risk when unprotected, putting the seroconversion rate (infection rate) at 0.9 per 100 person-years with condom, down from 6.7 per 100 person-years. The same review also found condom use significantly reduces the risk of gonorrhea for men.[43] A meta-analysis published in 2007, have shown condoms effectiveness to be approximately 80%.[44] Other sources estimate their effectiveness to 80-95%.[45]

A 2006 study reports that proper condom use decreases the risk of transmission for human papillomavirus by approximately 70%.[46] Another study in the same year found consistent condom use was effective at reducing transmission of herpes simplex virus-2 also known as genital herpes, in both men and women.[47]

Although a condom is effective in limiting exposure, some disease transmission may occur even with a condom. Infectious areas of the genitals, especially when symptoms are present, may not be covered by a condom, and as a result, some diseases can be transmitted by direct contact.[48] The primary effectiveness issue with using condoms to prevent STDs, however, is inconsistent use.[22]

Condoms may also be useful in treating potentially precancerous cervical changes. Exposure to human papillomavirus, even in individuals already infected with the virus, appears to increase the risk of precancerous changes. The use of condoms helps promote regression of these changes.[49] In addition, researchers in the UK suggest that a hormone in semen can aggravate existing cervical cancer, condom use during sex can prevent exposure to the hormone.[50]

Causes of failure

Condoms may slip off the penis after ejaculation,[51] break due to improper application or physical damage (such as tears caused when opening the package), or break or slip due to latex degradation (typically from usage past the expiration date, improper storage, or exposure to oils). The rate of breakage is between 0.4% and 2.3%, while the rate of slippage is between 0.6% and 1.3%.[43] Even if no breakage or slippage is observed, 1–2% of women will test positive for semen residue after intercourse with a condom.[52][53] "Double bagging," using two condoms at once, also increases the risk of condom failure.[54][55]

Different modes of condom failure result in different levels of semen exposure. If a failure occurs during application, the damaged condom may be disposed of and a new condom applied before intercourse begins — such failures generally pose no risk to the user.[56] One study found that semen exposure from a broken condom was about half that of unprotected intercourse; semen exposure from a slipped condom was about one-fifth that of unprotected intercourse.[57]

Standard condoms will fit almost any penis, although many condom manufacturers offer "snug" or "magnum" sizes. Some manufacturers also offer custom sized-to-fit condoms, with claims that they are more reliable and offer improved sensation/comfort.[14][58][59] Some studies have associated larger penises and smaller condoms with increased breakage and decreased slippage rates (and vice versa), but other studies have been inconclusive.[23]

Condom thickness is not associated with condom breakage, thinner condoms are as effective as thicker ones.[60] Nevertheless, it is recommended for condoms manufactures to avoid very thick, or very thin condoms, because they are both considered less effective.[61] Some authors even encourage users to choose thinner condoms "for greater durability, sensation, and comfort"[62], but others warn that "the thinner the condom, the smaller the force required to break it".[63]

Experienced condom users are significantly less likely to have a condom slip or break compared to first-time users, although users who experience one slippage or breakage are more likely to suffer a second such failure.[64] An article in Population Reports suggests that education on condom use reduces behaviors that increase the risk of breakage and slippage.[65] A Family Health International publication also offers the view that education can reduce the risk of breakage and slippage, but emphasizes that more research needs to be done to determine all of the causes of breakage and slippage.[23]

Among people who intend condoms to be their form of birth control, pregnancy may occur when the user has sex without a condom. The person may have run out of condoms, or be traveling and not have a condom with them, or simply dislike the feel of condoms and decide to "take a chance." This type of behavior is the primary cause of typical use failure (as opposed to method or perfect use failure).[66]

Another possible cause of condom failure is sabotage. One motive is to have a child against a partner's wishes or consent.[67] Some commercial sex workers from Nigeria reported clients sabotaging condoms in retaliation for being coerced into condom use.[68] Using a fine needle to make several pinholes at the tip of the condom is believed to significantly impact their effectiveness.[53][41]: 306–307

Prevalence

The prevalence of condom use varies greatly between countries. Most surveys of contraceptive use are among married women, or women in informal unions. Japan has the highest rate of condom usage in the world: in that country, condoms account for almost 80% of contraceptive use by married women. On average, in developed countries, condoms are the most popular method of birth control: 28% of married contraceptive users rely on condoms. In the average less-developed country, condoms are less common: only 6-8% of married contraceptive users choose condoms.[69]

Condom use for disease prevention also varies. Among gay men in the United States, one survey found that 35% had used two condoms at the same time, a practice called "double bagging".[70] (While intended to provide extra protection, double bagging actually increases the risk of condom failure.)

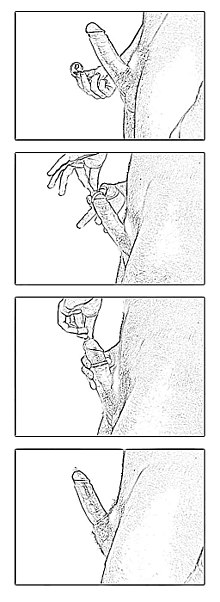

Use

Male condoms are usually packaged inside a foil wrapper, in a rolled-up form, and are designed to be applied to the tip of the penis and then unrolled over the erect penis. It is important that some space be left in the tip of the condom so that semen has a place to collect; otherwise it may be forced out of the base of the device. After use, it is recommended the condom be wrapped in tissue or tied in a knot, then disposed of in a trash receptacle.[71]

Some couples find that putting on a condom interrupts sex, although others incorporate condom application as part of their foreplay. Some men and women find the physical barrier of a condom dulls sensation. Advantages of dulled sensation can include prolonged erection and delayed ejaculation; disadvantages might include a loss of some sexual excitement.[39] Advocates of condom use also cite their advantages of being inexpensive, easy to use, and having few side effects.[72][39]

Role in sex education

Condoms are often used in sex education programs, because they have the capability to reduce the chances of pregnancy and the spread of some sexually transmitted diseases when used correctly. A recent American Psychological Association (APA) press release supported the inclusion of information about condoms in sex education, saying "comprehensive sexuality education programs... discuss the appropriate use of condoms", and "promote condom use for those who are sexually active."[73]

In the United States, teaching about condoms in public schools is opposed by some religious organizations.[74] Planned Parenthood, which advocates family planning and sex education, argues that no studies have shown abstinence-only programs to result in delayed intercourse, and cites surveys showing that 75% of American parents want their children to receive comprehensive sexuality education including condom use.[75]

Infertility treatment

Common procedures in infertility treatment such as semen analysis and intrauterine insemination (IUI) require collection of semen samples. These are most commonly obtained through masturbation, but an alternative to masturbation is use of a special collection condom to collect semen during sexual intercourse.

Collection condoms are made from silicone or polyurethane, as latex is somewhat harmful to sperm. Many men prefer collection condoms to masturbation, and some religions prohibit masturbation entirely. Also, compared with samples obtained from masturbation, semen samples from collection condoms have higher total sperm counts, sperm motility, and percentage of sperm with normal morphology. For this reason, they are believed to give more accurate results when used for semen analysis, and to improve the chances of pregnancy when used in procedures such as intracervical or intrauterine insemination.[76] Adherents of religions that prohibit contraception, such as Catholicism, may use collection condoms with holes pricked in them.[41]: 306–307

Condom therapy is sometimes prescribed to infertile couples when the female has high levels of antisperm antibodies. The theory is that preventing exposure to her partner's semen will lower her level of antisperm antibodies, and thus increase her chances of pregnancy when condom therapy is discontinued. However, condom therapy has not been shown to increase subsequent pregnancy rates.[77]

Other uses

Condoms excel as multipurpose containers because they are waterproof, elastic, durable, and will not arouse suspicion if found. Ongoing military utilization begun during World War II includes:

- Tying a non-lubricated condom over the muzzle of the rifle barrel in order to prevent barrel fouling by keeping out detritus.[78]

- The OSS used condoms for a plethora of applications, from storing corrosive fuel additives and wire garrotes (with the T-handles removed) to holding the acid component of a self-destructing film canister, to finding use in improvised explosives.[79]

- Navy SEALs have used doubled condoms, sealed with neoprene cement, to protect non-electric firing assemblies for underwater demolitions—leading to the term "Dual Waterproof Firing Assemblies."[80]

Other uses of condoms include:

- Covers for endovaginal ultrasound probes.[81] Covering the probe with a condom reduces the amount of blood and vaginal fluids that the technician must clean off between patients.

- Condoms can be used to hold water in emergency survival situations.[82]

- Condoms have also been used to smuggle cocaine and other drugs across borders and into prisons by filling the condom with drugs, tying it in a knot and then either swallowing it or inserting it into the rectum. These methods are very dangerous; if the condom breaks, the drugs inside can cause an overdose.[83]

- In Soviet gulags, condoms were used to smuggle alcohol into the camps by prisoners who worked outside during daylight. While outside, the prisoner would ingest an empty condom attached to a thin piece of rubber tubing, the end of which was wedged between his teeth. The smuggler would then use a syringe to fill the tubing and condom with up to three liters of raw alcohol, which the prisoner would then smuggle back into the camp. When back in the barracks, the other prisoners would suspend him upside down until all the spirit had been drained out. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn records that the three liters of raw fluid would be diluted to make seven liters of crude vodka, and that although such prisoners risked an extremely painful and unpleasant death if the condom burst inside them, the rewards granted them by other prisoners encouraged them to run the risk.[84]

- In his book entitled Last Chance to See, Douglas Adams reported having used a condom to protect a microphone he used to make an underwater recording. According to one of his traveling companions, this is standard BBC practice when a waterproof microphone is needed but cannot be procured.[85]

- Condoms are used by engineers to keep soil samples dry during soil tests.[86]

- Condoms are used in the field by engineers to initially protect sensors embedded in the steel or aluminum nose-cones of Cone Penetration Test (CPT) probes when entering the surface to conduct soil resistance tests to determine the bearing strength of soil.[87]

- Condoms are used as a one-way valve by paramedics when performing a chest decompression in the field. The decompression needle is inserted through the condom, and inserted into the chest. The condom folds over the hub allowing air to exit the chest, but preventing it from entering.[88]

Debate and criticism

While condom use has many proven benefits, a few detractors—notably the Roman Catholic Church—believe condoms cause negative social effects that outweigh the protection they provide to individuals who use them. Some researchers have expressed concern over certain ingredients sometimes added to condoms, notably talc and nitrosamines. In addition, the large-scale use of disposable condoms has resulted in concerns over their environmental impact.

Disposal and environmental impact

Experts, such as AVERT, recommend condoms be disposed of in a garbage receptacle, as flushing them down the toilet may cause plumbing blockages and other problems.[71][89]

While biodegradable,[71] latex condoms damage the environment when disposed of improperly. According to the Ocean Conservancy, condoms, along with certain other types of trash, cover the coral reefs and smother sea grass and other bottom dwellers. The United States Environmental Protection Agency also has expressed concerns that many animals might mistake the litter for food.[90]

Condoms made of polyurethane, a plastic material, do not break down at all. The plastic and foil wrappers condoms are packaged in are also not biodegradable. However, the benefits condoms offer are widely considered to offset their small landfill mass.[71] Frequent condom or wrapper disposal in public areas such as a parks have been seen as a persistent litter problem.[91]

Position of the Roman Catholic Church

The Roman Catholic Church directly condemns any artificial birth control or sexual acts, aside from intercourse between married heterosexuals.[92]

However, the use of condoms to combat STDs is not specifically addressed by Catholic doctrine, and is currently a topic of debate among theologians and high-ranking Catholic authorities. A few, such as Belgian Cardinal Godfried Danneels, believe the Catholic Church should actively support condoms used to prevent disease, especially serious diseases such as AIDS.

To date, statements from the Vatican have argued that condom-promotion programs encourage promiscuity, thereby actually increasing STD transmission.[93][94] In 2009, Pope Benedict XVI asserted that handing out condoms is not the solution to combating AIDS and actually makes the problem worse. [95]

The Roman Catholic Church is the largest organized body of any world religion.[96] This church has hundreds of programs dedicated to fighting the AIDS epidemic in Africa,[97] but its opposition to condom use in these programs has been highly controversial.[98]

Health issues

Dry dusting powders are applied to latex condoms before packaging to prevent the condom from sticking to itself when rolled up. Previously, talc was used by most manufacturers, but cornstarch is currently the most popular dusting powder.[99] Talc is known to be toxic if it enters the abdominal cavity (i.e. via the vagina). Cornstarch is generally believed to be safe, however some researchers have raised concerns over its use.[99][100]

Nitrosamines, which are potentially carcinogenic in humans,[101] are believed to be present in a substance used to improve elasticity in latex condoms.[102] A 2001 review stated that humans regularly receive 1,000 to 10,000 times greater nitrosamine exposure from food and tobacco than from condom use and concluded that the risk of cancer from condom use is very low.[103] However, a 2004 study in Germany detected nitrosamines in 29 out of 32 condom brands tested, and concluded that exposure from condoms might exceed the exposure from food by 1.5- to 3-fold.[102][104]

Cultural factors

Cultural attitudes toward gender, contraception, and sex affect condom use and perceptions about condoms around the world. In less-developed countries and among less-educated populations, misperceptions about how disease transmission and conception work may negatively affect the use of condoms. In cultures with more traditional gender roles, women may feel uncomfortable demanding that their partners use condoms.

Latino immigrants in the United States often face barriers to condom use. A study on female HIV prevention published in the Journal of Sex Health Research asserts that Latino women often lack the attitudes needed to negotiate safe sex due to traditional gender-role norms in the Latino community, and may be afraid to bring up the subject of condom use with their partners. Women who participated in the study often reported that their male partners would be angry or possibly violent at the suggestion that they use condoms.[105] A similar phenomenon has been noted in a survey of low-income African-American women; the women in this study also reported a fear of violence at the suggestion that condoms be used.[106]

A telephone survey conducted by Rand Corporation and Oregon State University and published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes showed that belief in AIDS conspiracy theories among black men is linked to rates of condom use; as conspiracy beliefs grew, consistent condom use dropped. Female use of condoms was not similarly affected.[107]

In Africa, condom promotion in some areas has been impeded by anti-condom campaigns by some Muslim[108] and Catholic clergy.[93] Some women in Africa believe that condoms are "for prostitutes" and that respectable women should not use them.[108] A few clergy even promote the idea that condoms are deliberately laced with HIV.[109]

Among the Massai in Tanzania, condom use is hampered by an aversion to "wasting" sperm, which is given sociocultural importance beyond reproduction. Sperm is believed to be an "elixir" to women and to have beneficial health effects. Massai women believe that, after conceiving a child, they must have sexual intercourse repeatedly so that the additional sperm aids the child's development. Frequent condom use is also considered by some Massai to cause impotence.[110]

In much of the Western world, the introduction of the pill in the 1960s was associated with a decline in condom use.[1]: 267–9, 272–5 In Japan, oral contraceptives were not approved for use until September 1999, and even then access was more restricted than in other industrialized nations.[111] Perhaps because of this restricted access to hormonal contraception, Japan has the highest rate of condom usage in the world: in 2008, 80% of contraceptive users relied on condoms.[69]

Major manufacturers

One analyst described the size of the condom market as something that "boggles the mind". Numerous small manufacturers, nonprofit groups, and government-run manufacturing plants exist around the world.[1]: 322, 328 Within the condom market, there are several major contributors, among them both for-profit businesses and philanthropic organizations. Most large manufacturers have ties to the business that reach back to the end of the 19th century.

- Julius Schmid, Inc. was founded in 1882 and began the Sheik and Ramses brands of condoms.[1]: 154–6 The London Rubber Company began manufacturing latex condoms in 1932, under the Durex brand.[1]: 199, 201, 218 Both companies are now part of Seton Scholl Limited.[1]: 327

- Youngs Rubber Company, founded by Merle Youngs in late nineteenth century America, introduced the Trojan line of condoms[1]: 191 now owned by Church and Dwight.[1]: 323–4

- Dunlop Rubber began manufacturing condoms in Australia in the 1890s. In 1905, Dunlop sold its condom-making equipment to one of its employees, Eric Ansell, who founded Ansell Rubber. In 1969, Ansell was sold back to Dunlop.[1]: 327 In 1987, English business magnate Richard Branson contracted with Ansell to help in a campaign against HIV and AIDS. Ansell agreed to manufacture the Mates brand of condom, to be sold at little or no profit in order to encourage condom use. Branson soon sold the Mates brand to Ansell, with royalty payments made annually to the charity Virgin Unite.[1]: 309, 311 [112] In addition to its Mates brand, Ansell currently manufactures Lifestyles for the U.S. market.[1]: 333

- In 1934 the Kokusia Rubber Company was founded in Japan. It is now known as the Okamoto Rubber Manufacturing Company.[1]: 257

- In 1970 Tim Black and Philip Harvey founded Population Planning Associates (now known as Adam & Eve). Population Planning Associates was a mail-order business that marketed condoms to American college students. Black and Harvey used the profits from their company to start a non-profit organization Population Services International,[1]: 286–7, 337–9 and Harvey later also founded another nonprofit company, DKT International, that annually sells millions of condoms at discounted rates in developing countries around the world.[1]: 286–7, 337–9

Research

A spray-on condom made of latex is intended to be easier to apply and more successful in preventing the transmission of diseases. As of 2009, the spray-on condom was not going to market because the drying time could not be reduced below two to three minutes.[113][114][115]

The Invisible Condom, developed at Université Laval in Québec, Canada, is a gel that hardens upon increased temperature after insertion into the vagina or rectum. In the lab, it has been shown to effectively block HIV and herpes simplex virus. The barrier breaks down and liquefies after several hours. As of 2005, the invisible condom is in the clinical trial phase, and has not yet been approved for use.[116]

Also developed in 2005 is a condom treated with an erectogenic compound. The drug-treated condom is intended to help the wearer maintain his erection, which should also help reduce slippage. If approved, the condom would be marketed under the Durex brand. As of 2007, it was still in clinical trials.[1]: 345

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br Collier, Aine (2007). The Humble Little Condom: A History. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-59102-556-6.

- ^ Oriel, JD (1994). The Scars of Venus: A History of Venereology. London: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-19844-X.

- ^ Diamond, Jared (1997). Guns, Germs and Steel. New York: W.W. Norton. p. 210. ISBN 0-393-03891-2.

- ^ "Special Topic: History of Condom Use". Population Action International. 2002. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ^ Youssef, H (1993). "The history of the condom". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 86 (4): 226–228. PMID 7802734. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|day=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Reprinted from India Rubber World (1891-01-31). "CHARLES GOODYEAR—The life and discoveries of the inventor of vulcanized India rubber". Scientific American Supplement (787). New York: Munn & Co. Retrieved 2008-06-08.

"The Charles Goodyear Story: The Strange Story of Rubber". Reader's Digest. Pleasantville, New York: The Reader's Digest Association. 1958. Retrieved 2008-06-08.{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Rubbers haven't always been made of rubber". Billy Boy: The excitingly different condom. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ "Biographical Note". The Margaret Sanger Papers. Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, Mass. 1995. Retrieved 2006-10-21.

- ^ Sharma, AP (2006). "Annual Report of the Tariff Commission" (PDF). India government: 9. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Collier, pp.267,285

- ^ "A Cluster of Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia among Homosexual Male Residents of Los Angeles and range Counties, California". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 31 (23). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 305–7. 1982-06-18. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ^ Adam, Barry D (2005). "AIDS optimism, condom fatigue, or self-esteem? Explaining unsafe sex among gay and bisexual men". Journal of Sex Research. FindArticles.com. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Walder, Rupert (2007-08-31). "Condom Fatigue in Western Europe?". Rupert Walder's blog. RH Reality Check. Retrieved 2008-06-29.

Jazz. "Condom Fatigue Or Prevention Fatigue". Isnare.com. Retrieved 2008-06-29. - ^ a b ""For Condoms, Maybe Size Matters After All"". CBS News. 2007-10-11. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ James, Susan (2002). "Of Lemons, Yams and Crocodile Dung: A Brief History of Birth Control" (PDF). University of Toronto Medical Journal. 79 (2): 156–158. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Thundy, Zacharias P (Summer 1985). "The Etymology of Condom". American Speech. 60 (2): 177–179. doi:10.2307/455309. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (2001). "Condom". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kruck, William E (1981). "Looking for Dr Condom". Publication of the American Dialect Society. 66 (7): 1–105.

- ^ "Condom". Mirriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "French letter". Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "Relationship of condom strength to failure during use". PIACT Prod News. 2 (2): 1–2. 1980. PMID 12264044.

- ^ a b Nordenberg, Tamar (1998). "Condoms: Barriers to Bad News". FDA Consumer magazine. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Spruyt, Alan B (1998). "Chapter 3: User Behaviors and Characteristics Related to Condom Failure". The Latex Condom: Recent Advances, Future Directions. Family Health International. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ a b "Lifestyles Condoms Introduces Polyisoprene Non-latex" (Press release). HealthNewsDigest.com. 2008-07-31. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ "Condoms". Condom Statistics and Sizes. 2008-03-12. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ a b "Nonlatex vs Latex Condoms: An Update". The Contraception Report. 14 (2). Contraception Online. 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Are polyurethane condoms as effective as latex ones?". Go Ask Alice!. February 22, 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ "Prefers polyurethane protection". Go Ask Alice!. March 4, 2005. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ a b "Polyisoprene Surgical Gloves". SurgicalGlove.net. 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ^ Boston Women's Health Book Collective (2005). Our Bodies, Ourselves: A New Edition for a New Era. New York, NY: Touchstone. p. 333. ISBN 0-7432-5611-5.

- ^ "Condoms: Extra protection". ConsumerReports.org. 2005. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kestelman, P; Trussell, J (1991). "Efficacy of the simultaneous use of condoms and spermicides". Fam Plann Perspect. 23 (5): 226–7, 232. doi:10.2307/2135759. PMID 1743276.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Nonoxynol-9 and the Risk of HIV Transmission". HIV/AIDS Epi Update. Health Canada, Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control. 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Nonoxynol-9 ineffective in preventing HIV infection". World Health Organization. 2006. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Boonstra, Heather (2005). "Condoms, Contraceptives and Nonoxynol-9: Complex Issues Obscured by Ideology". The Guttmacher Report on Public Policy. 8 (2). Retrieved 2007-04-08.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Stacey, Dawn. "Condom Types: A look at different condom styles". Retrieved 2008-12-08.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authorurl=ignored (help) - ^ "The Female Condom". AVERT. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ "Rape-aXe: Questions and answers". Rape-aXe. 2006. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ a b c d "Condom". Planned Parenthood. 2008. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ a b Hatcher, RA (2007). Contraceptive Technology (19th ed.). New York: Ardent Media. ISBN 1-59708-001-2. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Kippley, John (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th addition ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kippley, John (1996). The Art of Natural Family Planning (4th addition ed.). Cincinnati, OH: The Couple to Couple League. p. 146. ISBN 0-926412-13-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help), which cites:

- Guttmacher Institute (1992). "Choice of Contraceptives". The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics. 34: 111–114. doi:10.1016/j.<a.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help)

- Guttmacher Institute (1992). "Choice of Contraceptives". The Medical Letter on Drugs and Therapeutics. 34: 111–114. doi:10.1016/j.<a.

- ^ a b National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (2001-07-20). Workshop Summary: Scientific Evidence on Condom Effectiveness for Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD) Prevention (PDF). Hyatt Dulles Airport, Herndon, Virginia. pp. pp.13-15. Retrieved 2009-03-20.

{{cite conference}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Cayley, W.E. & Davis-Beaty, K. (2007). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. http://www.mrw.interscience.wiley.com/cochrane/clsysrev/articles/CD003255/frame.html.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Text "Effectiveness of Condoms in Reducing Heterosexual Transmission of HIV (Review)" ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization Department of Reproductive Health and Research (WHO/RHR) & Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Center for Communication Programs (CCP), INFO Project (2007). Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. INFO Project at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. p. 200.

- ^ Winer, R; Hughes, J; Feng, Q; O'Reilly, S; Kiviat, N; Holmes, K; Koutsky, L (2006). "Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women". N Engl J Med. 354 (25): 2645–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa053284+. PMID 16790697. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wald, Anna (2005). "The Relationship between Condom Use and Herpes Simplex Virus Acquisition". Annals of Internal Medicine. 143: 707–713. PMID 16287791. Retrieved 2007-04-07.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Villhauer, Tanya (2005-05-20). "Condoms Preventing HPV?". University of Iowa Student Health Service/Health Iowa. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Hogewoning, Cornelis J; Bleeker, MC; van den Bruler, AJ; et al. (2003). "Condom use Promotes the Regression of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia and Clearance of HPV: Randomized Clinical Trial". International Journal of Cancer. 107: 811–816. doi:10.1002/ijc.11474. PMID 14566832.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Semen can worsen cervical cancer". Medical Research Council (UK). Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sparrow, M; Lavill, K (1994). "Breakage and slippage of condoms in family planning clients". Contraception. 50 (2): 117–29. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(94)90048-5. PMID 7956211.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walsh, T; Frezieres, R; Peacock, K; Nelson, A; Clark, V; Bernstein, L; Wraxall, B (2004). "Effectiveness of the male latex condom: combined results for three popular condom brands used as controls in randomized clinical trials". Contraception. 70 (5): 407–13. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2004.05.008. PMID 15504381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Walsh, T; Frezieres, R; Nelson, A; Wraxall, B; Clark, V (1999). "Evaluation of prostate-specific antigen as a quantifiable indicator of condom failure in clinical trials". Contraception. 60 (5): 289–98. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(99)00098-0. PMID 10717781.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Does using two condoms provide more protection than using just one condom?". Condoms and Dental Dams. New York University Student Health Center. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ "Are two condoms better than one?". Go Ask Alice!. Columbia University. 2005-01-21. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ Richters, J; Donovan, B; Gerofi, J. "How often do condoms break or slip off in use?". Int J STD AIDS. 4 (2): 90–4. PMID 8476971.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Walsh, T; Frezieres, R; Peacock, K; Nelson, A; Clark, V; Bernstein, L; Wraxall, B (2003). "Use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) to measure semen exposure resulting from male condom failures: implications for contraceptive efficacy and the prevention of sexually transmitted disease". Contraception. 67 (2): 139–50. doi:10.1016/S0010-7824(02)00478-X. PMID 12586324.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ ""Next big thing, why condom size matters"". Menstruation.com. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ ""TheyFit: World's First Sized to Fit Condoms"". Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ^ Golombok, S., Harding, R. & Sheldon, J. (2001). "An evaluation of a thicker versus a standard condom with gay men". AIDS. 15: 245–250.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research (2004). The male latex condom: specification and guidelines for condom procurement 2003.

- ^ Corina, H. (2007). S.E.X.: The All-You-Need-To-Know Progressive Sexuality Guide to Get You Through High School and College. New York: Marlowe and Company. pp. 207–210. ISBN 978-1-60094-010-1.

- ^ World Health Organization and The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. "The male latex condom" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Valappil T, Kelaghan J, Macaluso M, Artz L, Austin H, Fleenor M, Robey L, Hook E (2005). "Female condom and male condom failure among women at high risk of sexually transmitted diseases". Sex Transm Dis. 32 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1097/01.olq.0000148295.60514.0b. PMID 15614119.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Steiner M, Piedrahita C, Glover L, Joanis C (1993). "Can condom users likely to experience condom failure be identified?". Fam Plann Perspect. 25 (5): 220–3, 226. doi:10.2307/2136075. PMID 8262171.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Liskin, Laurie (1991). "Condoms — Now More than Ever". Population Reports. H (8). Retrieved 2007-02-13.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Steiner, M; Cates, W; Warner, L (1999). "The real problem with male condoms is nonuse". Sex Transm Dis. 26 (8): 459–62. doi:10.1097/00007435-199909000-00007. PMID 10494937.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Childfree And The Media". Childfree Resource Network. 2000. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ Beckerleg, Susan; Gerofi, John (1999). "Investigation of Condom Quality: Contraceptive Social Marketing Programme, Nigeria" (PDF). Centre for Sexual & Reproductive Health: pp.6, 32. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b "Family Planning Worldwide: 2008 Data Sheet" (PDF). Population Reference Bureau. 2008. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) Data from surveys 1997–2007. - ^ Wolitski, RJ; Halkitis, PN; Parsons, JT; Gómez, CA (2001). "Awareness and use of untested barrier methods by HIV-seropositive gay and bisexual men". AIDS Educ Prev. 13 (4): 291–301. doi:10.1521/aeap.13.4.291.21430. PMID 11565589.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d "Environmentally-friendly condom disposal". Go Ask Alice!. December 20, 2002. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ^ "Male Condom". Feminist Women's Health Center. October 18, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-19.

- ^ "Based on the research, comprehensive sex education is more effective at stopping the spread of HIV infection, says APA committee" (Press release). American Psychological Association. February 23, 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

- ^ Rector, Robert E; Pardue, Melissa G; Martin, Shannan (January 28, 2004). "What Do Parents Want Taught in Sex Education Programs?". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2006-08-11.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "New Study Supports Comprehensive Sex Ed Programs". Planned Parenthood of Northeast Ohio. 2007-07-07. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Ellington, Joanna (January 2005). "Use of a Specialized Condom to Collect Sperm Samples for Fertility Procedures". INGfertility. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help), which references:- Sofikitis NV, Miyagawa I (1993). "Endocrinological, biophysical, and biochemical parameters of semen collected via masturbation versus sexual intercourse" (PDF). J. Androl. 14 (5): 366–73. PMID 8288490. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- Zavos PM (1985). "Seminal parameters of ejaculates collected from oligospermic and normospermic patients via masturbation and at intercourse with the use of a Silastic seminal fluid collection device". Fertil. Steril. 44 (4): 517–20. PMID 4054324.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

- ^ Franken D, Slabber C (1979). "Experimental findings with spermantibodies: condom therapy (a case report)". Andrologia. 11 (6): 413–6. PMID 532982.

Greentree L (1982). "Antisperm antibodies in infertility: the role of condom therapy". Fertil Steril. 37 (3): 451–2. PMID 7060795.

Kremer J, Jager S, Kuiken J (1978). "Treatment of infertility caused by antisperm antibodies". Int J Fertil. 23 (4): 270–6. PMID 33920.{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ambrose, Stephen E (1994). D-Day, June 6, 1944: the climactic battle of World War II. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-71359-0.

- ^ OSS Product Catalog, 1944

- ^ Couch, D (2001). The Warrior Elite: The forging of SEAL Class 228. ISBN 0-609-60710-3

- ^ Jimenez, R; Duff, P (1993). "Sheathing of the endovaginal ultrasound probe: is it adequate?". Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1 (1): 37–9. doi:10.1155/S1064744993000092. PMC 2364667. PMID 18476204.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ A broken photo probably of a condom carrying water[dead link]

- ^ "A 41-year-old man has been remanded in custody after being stopped on Saturday by customs officials at the Norwegian border at Svinesund. He had a kilo of cocaine in his stomach." Smuggler hospitalised as cocaine condom bursts

- ^ Applebaum, Anne (2004). Gulag : A History. Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor. pp. p.482. ISBN 1-4000-3409-4.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Carwardine, Mark; Adams, Douglas (1991). Last chance to see. [New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 0-517-58215-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kestenbaum, David (May 19, 2006). "A Failed Levee in New Orleans: Part Two". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ^ personal experience of L. Gow working on Chek Lap Kok airport platform/reclamation project 1992-94.

- ^ "Decompression of a Tension Pneumothorax" (PDF). Academy of medicine. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ "Using Condoms, Condom Types & Condom Sizes". AVERT. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Hightower, Eve (March–April 2003). "Clean sex, wasteful computers and dangerous mascara - Ask E". E - the environmental magazine. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Power, Robert. "The black plastic bag of qualitative research". Retrieved 2007-12-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|source=ignored (help) - ^ Pope Paul VI (1968-7-25). "Humanæ Vitæ". Retrieved 2009-7-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=and|date=(help) - ^ a b Alsan, Marcella (2006). "The Church & AIDS in Africa: Condoms & the Culture of Life". Commonweal: a Review of Religion, Politics, and Culture. 133 (8). Retrieved 2006-11-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Trujillo, Alfonso Cardinal López (2003-12-01). "Family Values Versus Safe Sex". Pontifical Council for the Family. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ "Condoms 'not the answer to AIDS': Pope". World News Australia. SBS. 2009-03-17. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "Major Branches of Religions". adherents.com. Retrieved 2006-09-14.

- ^ Karanja, David (2005). "Catholics fighting AIDS". Catholic Insight. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Barillari, Joseph (October 21, 2003). "Condoms and the church: a well-intentioned but deadly myth". Daily Princetonian. Retrieved 2007-12-23.

- ^ a b Gilmore, Caroline E (1998). "Chapter 4: Recent Advances in the Research, Development and Manufacture of Latex Rubber Condoms". The Latex Condom: Recent Advances, Future Directions. Family Health International. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ Wright, H; Wheeler, J; Woods, J; Hesford, J; Taylor, P; Edlich, R (1996). "Potential toxicity of retrograde uterine passage of particulate matter". J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 6 (3–4): 199–206. PMID 10167361.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Jakszyn, P; Gonzalez, C (2006). "Nitrosamine and related food intake and gastric and oesophageal cancer risk: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence". World J Gastroenterol. 12 (27): 4296–303. PMID 16865769. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b DW staff (2004-05-29). "German Study Says Condoms Contain Cancer-causing Chemical". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ^ Proksch, E (2001). "Toxicological evaluation of nitrosamines in condoms". Int J Hyg Environ Health. 204 (2–3): 103–10. doi:10.1078/1438-4639-00087+. PMID 11759152.

- ^ Altkofer, W; Braune, S; Ellendt, K; Kettl-Grömminger, M; Steiner, G (2005). "Migration of nitrosamines from rubber products—are balloons and condoms harmful to the human health?". Mol Nutr Food Res. 49 (3): 235–8. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200400050+. PMID 15672455.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gomez, Cynthia A (1996). "Gender, Culture, and Power: Barriers to HIV-Prevention Strategies for Women". The Journal of Sex Research. 33 (4): 355–362.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kalichman, SC (April 1998). "Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women". Journal of Women's Health. 7 (3): 371–378.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dotinga, Randy. "AIDS Conspiracy Theory Belief Linked to Less Condom Use". SexualHealth.com. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ a b "Muslim opposition to condoms limits distribution". PlusNews. Sept. 17, 2007. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Kamau, Pius (August 24, 2008). "Islam, Condoms and AIDS". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Coast, Ernestina (2007). "Wasting semen: context and condom use among the Maasai" (PDF). Culture, health, and sexuality. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ Hayashi, Aiko (2004-08-20). "Japanese Women Shun The Pill". CBS News. Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ^ The Healthcare Foundation, started by Virgin Group, changed names in 2004.

- ^ Lefevre, Callie (2008-08-13). "Spray-On Condoms: Still a Hard Sell". TIME Magazine. Retrieved 2009-07-26.

- ^ "Spray-On-Condom" (streaming video [Real format]). Schweizer Fernsehen News. November 29, 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Spray-On-Condom" (html). Institut für Kondom-Beratung. 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-03.

- ^ "Safety, Tolerance and Acceptability Trial of the Invisible Condom in Healthy Women". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-14.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Green, Shirley (1972). The Curious History of Contraception. New York: St. Martin's Press.

External links

- Male Latex Condoms and Sexually Transmitted Diseases — from the US Center for Disease Control.

- How To Put On A Condom — from VideoJug