Meloxicam

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Mobic, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601242 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, intravenous |

| Drug class | Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 89%[8] |

| Protein binding | 99.4%[8] |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C9 and 3A4-mediated)[8] |

| Elimination half-life | 20 hours[8] |

| Excretion | Urine and feces equally[8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.113.257 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

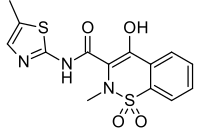

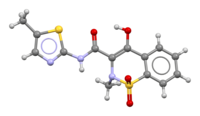

| Formula | C14H13N3O4S2 |

| Molar mass | 351.40 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Meloxicam, sold under the brand name Mobic among others, is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to treat pain and inflammation in rheumatic diseases and osteoarthritis.[9][10] It is taken by mouth or given by injection into a vein.[10][11] It is recommended that it be used for as short a period as possible and at a low dose.[10]

Common side effects include abdominal pain, dizziness, swelling, headache, and a rash.[10] Serious side effects may include heart disease, stroke, kidney problems, and stomach ulcers.[10] Use is not recommended in the third trimester of pregnancy.[10] It blocks cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) more than it blocks cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1).[10] It is in the oxicam family of chemicals and is closely related to piroxicam.[10]

Meloxicam was patented in 1977 and approved for medical use in the United States in 2000.[10][12] It was developed by Boehringer Ingelheim and is available as a generic medication.[10] In 2022, it was the 29th most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 18 million prescriptions.[13][14] An intravenous version of meloxicam (Anjeso) was approved for medical use in the United States in February 2020.[15][11]

Adverse effects

[edit]Meloxicam use can result in gastrointestinal toxicity and bleeding, headaches, rash, and very dark or black stool (a sign of intestinal bleeding). It has fewer gastrointestinal side effects than diclofenac,[16] piroxicam,[17] naproxen,[18] and perhaps all other NSAIDs which are not COX-2 selective.[16]

In October 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) required the prescription drug label to be updated for all nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications to describe the risk of kidney problems in unborn babies that result in low amniotic fluid.[19][20] They recommend avoiding NSAIDs in pregnant women at 20 weeks or later in pregnancy.[19][20]

Cardiovascular

[edit]Like other NSAIDs, its use is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke.[21] Although meloxicam inhibits formation of thromboxane A, it does not appear to do so at levels that would interfere with platelet function.[22][23] A pooled analysis of randomized, controlled studies of meloxicam therapy of up to 60 days duration found that meloxicam was associated with a statistically significantly lower number of thromboembolic complications than the NSAID diclofenac (0.2% versus 0.8% respectively) but a similar incidence of thromboembolic events to naproxen and piroxicam.[24]

People with hypertension, high cholesterol, or diabetes are at risk for cardiovascular side effects. People with family history of heart disease, heart attack, or stroke should tell their treating physician as the potential for serious cardiovascular side effects is significant.[25][26]

Gastrointestinal

[edit]NSAIDs cause an increase in the risk of serious gastrointestinal adverse events including bleeding, ulceration, and perforation of the stomach or intestines, which can be fatal. Elderly patients are at greater risk for serious gastrointestinal events.[27]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Meloxicam blocks cyclooxygenase (COX), the enzyme responsible for converting arachidonic acid into prostaglandin H2—the first step in the synthesis of prostaglandins, which are mediators of inflammation. Meloxicam has been shown, especially at low therapeutic doses, to selectively inhibit COX-2 over COX-1.[8]

Meloxicam concentrations in synovial fluid range from 40% to 50% of those in plasma. The free fraction in synovial fluid is 2.5 times higher than in plasma, due to the lower albumin content in synovial fluid compared to plasma. The significance of this penetration is unknown,[27] but it may account for the fact that it performs exceptionally well in treatment of arthritis in animal models.[28]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absorption

[edit]The bioavailability of meloxicam is decreased when administered orally compared to an equivalent IV bolus dose. Different oral formulations of meloxicam are not bioequivalent.[10] Use of oral meloxicam following a high-fat breakfast increases the mean peak drug levels by about 22%; however, the manufacturer does not make any specific meal recommendations. In addition, the use of antacids does not show pharmacokinetic interactions.[4] With chronic dosing, the time to maximum plasma concentration following oral administration is approximately 5–6 hours.[29]

Distribution

[edit]The mean volume of distribution of meloxicam is approximately 10 L. It is highly protein-bound, mainly to albumin.[23][29]

Metabolism

[edit]Meloxicam is extensively metabolized in the liver by the enzymes CYP2C9 and CYP3A4 (minor) into four inactive metabolites. Peroxidase activity is thought to be responsible for the other two remaining metabolites.[4][30]

Excretion

[edit]Meloxicam is predominantly excreted in the form of metabolites and occurs to equal extents in the urine and feces.[4] Traces of unchanged parent drug are found in urine and feces.[4] The mean elimination half-life ranges from 15 to 20 hours.[4]

Specific populations

[edit]The use of meloxicam is not recommended in people with peptic ulcer disease or increased gastrointestinal bleeding risk, including those over 75 years of age or those taking medications associated with bleeding risk.[31]

Adverse events are dose-dependent and associated with length of treatment.[31][4]

Veterinary use

[edit]Meloxicam is used in veterinary medicine mainly to treat dogs,[32][33] but also sees off-label use in other animals such as cattle and exotics.[34][35] In the European Union and other countries it is not considered off-label and can be used in cattle, pigs, horses, dogs, cats and guinea pigs.[36] It has also been investigated as an alternative to diclofenac by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) to prevent deaths of vultures.[37]

Depending on the animal species, each country or union of countries applies different guidelines or legal frameworks for the use of the drug, as well as different recorded side effects. The most common side effects in dogs include gastrointestinal irritation (vomiting, diarrhea, and ulceration).[32] As far as the perioperative administration is concerned, in healthy dogs given meloxicam, no perioperative adverse effects on the cardiovascular system have been reported at recommended dosages.[38] Perioperative administration of meloxicam to cats did not affect postoperative respiratory rate nor heart rate.[39]

Use of meloxicam in cats

[edit]The issue of using meloxicam in cats involves conflicting guidelines, differing legislation, and a narrow therapeutic safety margin that can easily turn the drug from cure to poison. More specifically:

US policy vs EU policy

[edit]The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approves the use of meloxicam in cats only in injectable form and only as a one-time injection given before surgery.[40][41] It does not approve meloxicam oral suspension for cats and it does not approve meloxicam spray for cats because after reviewing numerous reports of meloxicam side effects in cats, it has identified many cases of acute renal failure and death and has added the following boxed warning to the products' label: "Repeated use of meloxicam in cats has been associated with acute renal failure and death. Do not administer additional injectable or oral meloxicam to cats. See Contraindications, Warnings, and Precautions for detailed information."[42]

In contrast, in the European Union and other continents or countries, the use of the drug in cats is allowed with no such warning.[43][44] The product instruction leaflet for meloxicam for cats in the form of oral suspension 0.5 mg/ml states that: "Typical adverse reactions of NSAIDs such as loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhoea, faecal occult blood, apathy, and renal failure have occasionally been reported. These side effects are in most cases transient and disappear following termination of the treatment but in very rare cases may be serious or fatal."[45]

Dosage and safety margin

[edit]The data sheets for meloxicam products for cats also state that: "Meloxicam has a narrow therapeutic safety margin in cats and clinical signs of overdose may be seen at relatively small overdose levels."[45] The dosage policy for meloxicam oral suspension products for cats as described in the data sheets defines the amount administered as proportional to body weight. There is no separate dosage guideline for overweight or obese cats. Similarly, there is no separate dosage instruction for elderly cats.

This information is important because, shifting attention briefly to the human medical field, where more studies have been conducted, there are medical opinions suggesting that the typical dosage of certain medications can lead to toxicity if factors such as obesity[46] or the patient’s age[47] are not taken into account.

Additional studies

[edit]Some additional information about giving meloxicam to cats from researchers is as follows: A peer-reviewed journal article cites NSAIDs, including meloxicam, as causing gastrointestinal upset and, at high doses, acute kidney injury and CNS signs such as seizures and comas in cats. It adds that cats have a low tolerance for NSAIDs.[48][49] Also, in another scientific journal there is talk of research according to which cats that received meloxicam had greater proteinuria at 6 months than cats that received placebo. It was concluded that meloxicam should be used with caution in cats with chronic kidney disease.[50]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]In dogs, the absorption of meloxicam from the stomach is not affected by the presence of food,[51] with the peak concentration (Cmax) of meloxicam occurring in the blood 7–8 hours after administration.[51] The half-life of meloxicam is approximately 24 hours in dogs.[51] In the koala (Phascolarctos cinereus), very little meloxicam is absorbed into the blood after oral administration (that is, it has poor bioavailability).[52]

Legal status

[edit]United States

[edit]2003: Meloxicam was approved in the US for use in dogs for the management of pain and inflammation associated with osteoarthritis, as an oral (liquid) formulation of meloxicam.[53]

2003 (November): An injectable formulation for use in dogs was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[54]

2004 (October): A formulation for use in cats was approved for use before surgery only.[55] This is an injectable meloxicam, indicated for as a single, one-time dose only, with specific and repeated warnings not to administer a second dose.[56]

2005 (January): The product insert added a warning in bold-face type: "Do not use in cats."[57]

2005: The FDA sent a Notice of Violation to the manufacturer for its promotional materials which included promotion of the drug for off-label use.[58]

2020 (February): A meloxicam injection was approved for use in the United States. Specifically, the FDA granted the approval of Anjeso to Baudax Bio.[11][59]

European Union

[edit]In the European Union, meloxicam is licensed for other anti-inflammatory benefits including relief from both acute and chronic pain in dogs. Meloxicam is also licensed for use in horses, to relieve the pain associated with musculoskeletal disorders.[60]

1998 (January): Meloxicam was authorised for use in cattle throughout the European Union, via a centralised marketing authorisation.[61]

2006: The first generic meloxicam product was approved.[61]

2024 (January): EMA issued an 'Opinion'[62] on a change to this medicine's authorisation concerning the follow-up oral treatment after initial injectable administration in cats. This change remains as an 'Opinion', while the medication continues to be approved as usual.[63]

Other countries

[edit]As of June 2008[update], meloxicam is registered for long-term use in cats in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada.[64]

In the United Kingdom, meloxicam is licensed for use in cats, guinea pigs, horses, and livestock including pigs and cattle. [65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Mobic- meloxicam tablet". DailyMed. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Anjeso- meloxicam injection". DailyMed. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Loxitab EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 8 September 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- ^ "Metacam EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 31 July 2006. Retrieved 3 December 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Noble S, Balfour JA (March 1996). "Meloxicam". Drugs. 51 (3): 424–30, discussion 431–32. doi:10.2165/00003495-199651030-00007. PMID 8882380. S2CID 260452199.

- ^ British national formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. pp. 1112–1113. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Meloxicam Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ^ a b c "Baudax Bio Announces FDA Approval of Anjeso for the Management of Moderate to Severe Pain". Baudax Bio, Inc. (Press release). 20 February 2020. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 519. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 10 July 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Meloxicam Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Anjeso- meloxicam injection". DailyMed. 22 February 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b Hawkey C, Kahan A, Steinbrück K, Alegre C, Baumelou E, Bégaud B, et al. (September 1998). "Gastrointestinal tolerability of meloxicam compared to diclofenac in osteoarthritis patients. International MELISSA Study Group. Meloxicam Large-scale International Study Safety Assessment". British Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (9): 937–45. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.937. PMID 9783757.

- ^ Dequeker J, Hawkey C, Kahan A, Steinbrück K, Alegre C, Baumelou E, et al. (September 1998). "Improvement in gastrointestinal tolerability of the selective cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 inhibitor, meloxicam, compared with piroxicam: results of the Safety and Efficacy Large-scale Evaluation of COX-inhibiting Therapies (SELECT) trial in osteoarthritis". British Journal of Rheumatology. 37 (9): 946–51. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/37.9.946. PMID 9783758.

- ^ Wojtulewski JA, Schattenkirchner M, Barceló P, Le Loët X, Bevis PJ, Bluhmki E, et al. (April 1996). "A six-month double-blind trial to compare the efficacy and safety of meloxicam 7.5 mg daily and naproxen 750 mg daily in patients with rheumatoid arthritis". British Journal of Rheumatology. 35 (Suppl 1): 22–8. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/35.suppl_1.22. PMID 8630632.

- ^ a b "FDA Warns that Using a Type of Pain and Fever Medication in Second Half of Pregnancy Could Lead to Complications". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). 15 October 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b "NSAIDs may cause rare kidney problems in unborn babies". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 21 July 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Stamm O, Latscha U, Janecek P, Campana A (January 1976). "Development of a special electrode for continuous subcutaneous pH measurement in the infant scalp". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 124 (2): 193–195. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(16)33297-5. PMID 2012.

- ^ Zeidan AZ, Al Sayed B, Bargaoui N, Djebbar M, Djennane M, Donald R, et al. (April 2013). "A review of the efficacy, safety, and cost-effectiveness of COX-2 inhibitors for Africa and the Middle East region". Pain Practice. 13 (4): 316–331. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00591.x. PMID 22931375. S2CID 205715393.

- ^ a b Gates BJ, Nguyen TT, Setter SM, Davies NM (October 2005). "Meloxicam: a reappraisal of pharmacokinetics, efficacy and safety". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy. 6 (12): 2117–2140. doi:10.1517/14656566.6.12.2117. PMID 16197363. S2CID 25512189.

Meloxicam is extensively bound to plasma proteins (99.4%), primarily to albumin. Meloxicam has an apparent volume of distribution (Vd) 10 – 15 L in humans (0.1 – 0.2 L/kg) after oral administration and a mean volume of distribution at steady-state of 0.2 L/kg after intravenous administration."

"None of the meloxicam treatment groups demonstrated inhibition of platelet aggregation to either arachidonic acid (AC) or adenosine diphosphate (ADP). However, there were no significant changes in the platelet count, prothrombin, and activated partial thromboplastin time in any of the meloxicam and indomethacin groups. Other crossover studies also confirmed that meloxicam 15 mg/day caused a major reduction of maximum thromboxane production, but no reduction in collagen- or AC-induced platelet aggregation. - ^ Singh G, Lanes S, Triadafilopoulos G (July 2004). "Risk of serious upper gastrointestinal and cardiovascular thromboembolic complications with meloxicam". The American Journal of Medicine. 117 (2): 100–106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.03.012. PMID 15234645.

- ^ "Meloxicam". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ "Meloxicam". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 16 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- ^ a b "Meloxicam official FDA information, side effects, and uses". Drugs.com. March 2010. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Engelhardt G, Homma D, Schlegel K, Utzmann R, Schnitzler C (October 1995). "Anti-inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic and related properties of meloxicam, a new non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agent with favourable gastrointestinal tolerance". Inflammation Research. 44 (10): 423–33. doi:10.1007/BF01757699. PMID 8564518. S2CID 37937305.

- ^ a b Bekker A, Kloepping C, Collingwood S (2018). "Meloxicam in the management of post-operative pain: Narrative review". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 34 (4): 450–457. doi:10.4103/joacp.JOACP_133_18. PMC 6360894. PMID 30774225.

- ^ "Meloxicam (Professional Patient Advice)". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 6 August 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ a b 2019 American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel (April 2019). "American Geriatrics Society 2019 Updated AGS Beers Criteria® for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults". Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 67 (4): 674–694. doi:10.1111/jgs.15767. PMID 30693946. S2CID 59338182.

- ^ a b "Metacam- meloxicam suspension". DailyMed. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ "Metacam- meloxicam injection, solution". DailyMed. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Off-label use discussed in: Arnold Plotnick MS, DVM, ACVIM, ABVP, Pain Management using Metacam Archived 14 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, and Stein, Robert, Perioperative Pain Management Archived 18 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine Part IV, Looking Beyond Butorphanol, Sep 2006, Veterinary Anesthesia & Analgesia Support Group.

- ^ For off-label use example in rabbits, see Krempels, Dana, Hind Limb Paresis and Paralysis in Rabbits Archived 17 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, University of Miami Biology Department.

- ^ "Metacam". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 31 July 2006. Retrieved 17 November 2024.

- ^ Swan G, Naidoo V, Cuthbert R, Green RE, Pain DJ, Swarup D, et al. (March 2006). "Removing the threat of diclofenac to critically endangered Asian vultures". PLOS Biology. 4 (3): e66. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040066. PMC 1351921. PMID 16435886.

- ^ Boström IM, Nyman G, Hoppe A, Lord P (January 2006). "Effects of meloxicam on renal function in dogs with hypotension during anaesthesia". Veterinary Anaesthesia and Analgesia. 33 (1): 62–9. doi:10.1111/j.1467-2995.2005.00208.x. PMID 16412133.

- ^ Höglund OV, Dyall B, Gräsman V, Edner A, Olsson U, Höglund K (October 2018). "Effect of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on postoperative respiratory and heart rate in cats subjected to ovariohysterectomy". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 20 (10): 980–984. doi:10.1177/1098612X17742290. PMC 11129237. PMID 29165006. S2CID 30649716.

- ^ Center for Veterinary Medicine (29 September 2022). "Get the Facts about Pain Relievers for Pets". FDA.

- ^ Center for Veterinary Medicine (15 August 2023). "What Veterinarians Should Advise Clients About Pain Control and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) in Dogs and Cats". FDA.

- ^ Center for Veterinary Medicine (14 August 2023). "Information about the Boxed Warning on Meloxicam Labels regarding Safety Risks in Cats". FDA.

- ^ "Metacam". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 31 July 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ "Cats: Meloxicam Question for Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs". UK Parliament Written questions, answers and statements.

- ^ a b "Clinical particulars - Meloxidyl 0.5 mg/ml oral suspension for cats". www.noahcompendium.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2024.

- ^ Barras M, Legg A (October 2017). "Drug dosing in obese adults". Australian Prescriber. 40 (5): 189–193. doi:10.18773/austprescr.2017.053. PMC 5662437. PMID 29109603.

- ^ Turnheim K (2004). "Drug therapy in the elderly". Experimental Gerontology. 39 (11–12): 1731–1738. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2004.05.011. ISSN 0531-5565. PMID 15582289.

- ^ "Toxicology Brief: The 10 most common toxicoses in cats". Dvm360. 1 June 2006. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Merola V, Dunayer E (June 2006). "The 10 most common toxicoses in cats" (PDF). Veterinary Medicine: 340–342. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- ^ KuKanich K, George C, Roush JK, Sharp S, Farace G, Yerramilli M, et al. (February 2021). "Effects of low-dose meloxicam in cats with chronic kidney disease". Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 23 (2): 138–148. doi:10.1177/1098612X20935750. PMC 10741344. PMID 32594827. S2CID 220256059.

- ^ a b c Khan SA, McLean MK (March 2012). "Toxicology of frequently encountered nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in dogs and cats". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice. 42 (2): 289–306, vi–vii. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.01.003. PMID 22381180.

- ^ Kimble B, Black LA, Li KM, Valtchev P, Gilchrist S, Gillett A, et al. (October 2013). "Pharmacokinetics of meloxicam in koalas (Phascolarctos cinereus) after intravenous, subcutaneous and oral administration". Journal of Veterinary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 36 (5): 486–93. doi:10.1111/jvp.12038. PMID 23406022.

- ^ "NADA 141-213: New Animal Drug Application Approval (for Metacam (meloxicam) 0.5 mg/mL and 1.5 mg/mL Oral Suspension)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 April 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ^ "NADA 141-219: Metacam (meloxicam) 5 mg/mL Solution for Injection" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 12 November 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Metacam 5 mg/mL Solution for Injection, Supplemental Approval" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 28 October 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ See the manufacturer's FAQ Archived 2 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine on its website, and its clinical dosing instructions for cats. Archived 6 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Client Information Sheet For Metacam (meloxicam) 1.5 mg/mL Oral Suspension" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). January 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 November 2017.

Metacam is a prescription non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is used to control pain and inflammation (soreness) due to osteoarthritis in dogs. Osteoarthritis (OA) is a painful condition caused by "wear and tear" of cartilage and other parts of the joints that may result in the following changes or signs in your dog: Limping or lameness, decreased activity or exercise (reluctance to stand, climb stairs, jump or run, or difficulty in performing these activities), stiffness or decreased movement of joints. Metacam is given to dogs by mouth. Do not use Metacam Oral Suspension in cats. Acute kidney injury and death have been associated with the use of meloxicam in cats.

- ^ "Notice of Violation" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 19 April 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ^ "Anjeso (meloxicam) injection, for intravenous use" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 February 2020. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Maddison JE, Page SW, Church D, eds. (2008). "Meloxicam". Small animal clinical pharmacology (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Saunders/Elsevier. pp. 301–302. ISBN 9780702028588.

- ^ a b Wright E (March 2007). "Generic and biosimilar medicinal products in the European Union" (PDF). Chemistry Today. 25 (2): 4–6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Metacam - opinion on variation to marketing authorisation". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 19 January 2024. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ "Metacam". European Medicines Agency (EMA). 31 July 2006. Retrieved 16 November 2024.

- ^ Gaschen FP, Schaer M, eds. (2016). "Recent NSAID developments". Clinical medicine of the dog and cat (3rd ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781482226065. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ^ "Product Information Database". Veterinary Medicines Directorate. DEFRA. Retrieved 29 March 2023.