Grand Palace

| The Grand Palace | |

|---|---|

พระบรมมหาราชวัง | |

Seen from across the Chao Phraya River in 2017 | |

| General information | |

| Status | The King's private property[1][2] |

| Location | Phra Nakhon, Bangkok, Thailand |

| Coordinates | 13°45′00″N 100°29′31″E / 13.7501°N 100.4920°E |

| Construction started | 6 May 1782 |

| Completed | 1925 |

| Owner | Vajiralongkorn |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 218.415,047 m2 (2,351,000 sq ft) |

| Website | |

| www.royalgrandpalace.th | |

The Grand Palace (Thai: พระบรมมหาราชวัง, RTGS: Phra Borom Maha Ratcha Wang[3] lit. 'The Supreme Grand Palace') is a complex of buildings at the heart of Bangkok, Thailand. The palace has been the official residence of the Kings of Siam (and later Thailand) since 1782. The king, his court, and his royal government were based on the grounds of the palace until 1925. King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX), resided at the Chitralada Royal Villa and his successor King Vajiralongkorn (Rama X) resides at the Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall, both in the Dusit Palace, but the Grand Palace is still used for official events. Several royal ceremonies and state functions are held within the walls of the palace every year. The palace is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Thailand, with over eight million people visiting each year.[4]

Construction of the palace began on 6 May 1782, at the order of King Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I), the founder of the Chakri dynasty, when he moved the capital city from Thonburi to Bangkok.

Throughout successive reigns, many new buildings and structures were added, especially during the reign of King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). By 1925, the king, the Royal Family and the government were no longer permanently settled at the palace, and had moved to other residences. After the abolition of absolute monarchy in 1932, all government agencies completely moved out of the palace.

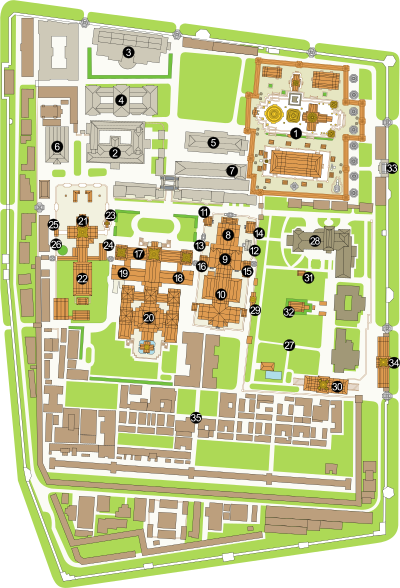

In shape, the palace complex is roughly rectangular and has a combined area of 218,400 square metres (2,351,000 sq ft), surrounded by four walls. It is situated on the banks of the Chao Phraya River at the heart of the Rattanakosin Island, today in the Phra Nakhon District. The Grand Palace is bordered by Sanam Luang and Na Phra Lan Road to the north, Maharaj Road to the west, Sanam Chai Road to the east and Thai Wang Road to the south.

Rather than being a single structure, the Grand Palace is made up of numerous buildings, halls, pavilions set around open lawns, gardens and courtyards. Its asymmetry and eclectic styles are due to its organic development, with additions and rebuilding being made by successive reigning kings over 200 years of history. It is divided into several quarters: the Temple of the Emerald Buddha; the Outer Court, with many public buildings; the Middle Court, including the Phra Maha Monthien Buildings, the Phra Maha Prasat Buildings and the Chakri Maha Prasat Buildings; the Inner Court and the Siwalai Gardens quarter. The Grand Palace is currently partially open to the public as a museum, but it remains a working palace, with several royal offices still situated inside.

History

[edit]| Monarchs of the Chakri dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I) | |

| Phutthaloetla Naphalai (Rama II) | |

| Nangklao (Rama III) | |

| Mongkut (Rama IV) | |

| Chulalongkorn (Rama V) | |

| Vajiravudh (Rama VI) | |

| Prajadhipok (Rama VII) | |

| Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) | |

| Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX) | |

| Vajiralongkorn (Rama X) | |

The construction of the Grand Palace began on 6 May 1782, at the order of King Phutthayotfa Chulalok (Rama I).[5] Having seized the crown from King Taksin of Thonburi, King Rama I was intent on building a capital city for his new Chakri dynasty. He moved the seat of power from the city of Thonburi, on the west side of the Chao Phraya River, to the east side at Bangkok. The new capital city was turned into an artificial island when canals were dug along the east side. The island was given the name 'Rattanakosin'. The previous royal residence was the Derm Palace, constructed for King Taksin in 1768.[6][7] The old royal palace in Thonburi was small and sandwiched between two temples; Wat Arun and Wat Tai Talat, prohibiting further expansion.[8]

The new palace was built on a rectangular piece of land on the very west side of the island, between Wat Pho to the south, Wat Mahathat to the north and with the Chao Phraya River on the west. This location was previously occupied by a Chinese community, whom King Rama I ordered to relocate to an area south and outside of the city walls; the area is now Bangkok's Chinatown.[6][7]

Desperate for materials and short on funds, the palace was initially built entirely out of wood, its various structures surrounded by a simple log palisade. On 10 June 1782, the king ceremonially crossed the river from Thonburi to take permanent residence in the new palace. Three days later on 13 June, the king held an abbreviated coronation ceremony, thus becoming the first monarch of the new Rattanakosin Kingdom.[5][9] Over the next few years the king began replacing wooden structures with masonry, rebuilding the walls, forts, gates, throne halls and royal residences. This rebuilding included the royal chapel, which would come to house the Emerald Buddha.[6][7]

To find more material for these constructions, King Rama I ordered his men to go upstream to the old capital city of Ayutthaya, which was destroyed in 1767 during a war between Burma and Siam. They dismantled structures and removed as many bricks as they could find, while not removing any from the temples. They began by taking materials from the forts and walls of the city. By the end they had completely leveled the old royal palaces. The bricks were ferried down the Chao Phraya by barges, where they were eventually incorporated into the walls of Bangkok and the Grand Palace itself.[10][11] Most of the initial construction of the Grand Palace during the reign of King Rama I was carried out by conscripted or corvée labour.[12] After the final completion of the ceremonial halls of the palace, the king held a full traditional coronation ceremony in 1785.[6][13]

The layout of the Grand Palace followed that of the Royal Palace at Ayutthaya in location, organization, and in the divisions of separate courts, walls, gates and forts.[10][14] Both palaces featured a proximity to the river. The location of a pavilion serving as a landing stage for barge processions also corresponded with that of the old palace. To the north of the Grand Palace there is a large field, the Thung Phra Men (now called Sanam Luang), which is used as an open space for royal ceremonies and as a parade ground. There was also a similar field in Ayutthaya, which was used for the same purpose. The road running north leads to the Front Palace, the residence of the Vice King of Siam.[15][16]

The Grand Palace is divided into four main courts, separated by numerous walls and gates: the Outer Court, the Middle Court, the Inner Court and the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. Each of these court's functions and access are clearly defined by laws and traditions. The Outer Court is in the northwestern part of the Grand Palace; within are the royal offices and (formerly) state ministries.[15][17] To the northeast is the Temple of the Emerald Buddha, the royal chapel, and home of the Emerald Buddha. The Middle Court housed the most important state apartments and ceremonial throne halls of the king. The Inner Court, at the south end of the complex, was reserved only for females, as it housed the king's harem.[18][19]

During the reign of King Phutthaloetla Naphalai (Rama II), the area of the Grand Palace was expanded southwards up to the walls of Wat Pho. Previously this area was home to offices of various palace officials. This expansion increased the area of the palace from 213,674 square metres (2,299,970 sq ft) to 218,400 square metres (2,351,000 sq ft). New walls, forts, and gates were constructed to accommodate the enlarged compound. Since this expansion, the palace has remained within its walls with new construction and changes being made only on the inside.[15][20]

In accordance with tradition, the palace was initially referred to only as the Phra Ratcha Wang Luang (พระราชวังหลวง) or 'Royal Palace', similar to the old palace in Ayutthaya. However, during the reign of King Mongkut (Rama IV) the name Phra Boromma Maha Ratcha Wang or 'Grand Palace' was first used in official documents. This change of name was made during the elevation of Prince Chutamani (the king's younger brother) to the title of Second King Pinklao in 1851. The proclamation of his title described the royal palace as the 'supreme' (บรม; Borom)[3] and 'great' (มหา; Maha)[3] palace. This title was given in order to distinguish the palace from the Second King's palace (the Front Palace), which was described as the Phra Bovorn Ratcha Wang (พระบวรราชวัง) or the 'glorious' (บวร; Bovorn) palace.[21]

Throughout the period of absolute monarchy, from 1782 to 1932, the Grand Palace was both the country's administrative and religious centre.[22] As the main residence of the monarch, the palace was also the seat of government, with thousands of inhabitants including guardsmen, servants, concubines, princesses, ministers, and courtiers. The palace's high whitewashed castellated walls and extensive forts and guard posts mirrored those of the walls of Bangkok itself, and thus the Grand Palace was envisioned as a city within a city. For this reason a special set of palace laws were created to govern the inhabitants and to establish hierarchy and order.[23]

By the 1920s, a series of new palaces were constructed elsewhere for the king's use; these included the more modern Dusit Palace, constructed in 1903, and Phaya Thai Palace in 1909. These other Bangkok residences began to replace the Grand Palace as the primary place of residence of the monarch and his court. By 1925 this gradual move out of the palace was complete. The growth and centralization of the Siamese state also meant that the various government ministries have grown in size and were finally moved out of the Grand Palace to their own premises. Despite this the Grand Palace remained the official and ceremonial place of residence as well as the stage set for elaborate ancient ceremonies of the monarchy. The end of the absolute monarchy came in 1932, when a revolution overthrew the ancient system of government and replaced it with a constitutional monarchy.[23][24]

Today the Grand Palace is still a centre of ceremony and of the monarchy, and serves as a museum and tourist attraction as well.[23]

Outer Court

[edit]

The Outer Court or Khet Phra Racha Than Chan Nork (เขตพระราชฐานชั้นนอก) of the Grand Palace is situated to the northwest of the palace (the northeast being occupied by the Temple of the Emerald Buddha). Entering through the main Visetchaisri Gate, the Temple of the Emerald Buddha is located to the left, with many public buildings located to the right.[19]

These buildings include the headquarters and information centre of the Grand Palace and the Bureau of the Royal Household. Other important buildings inside the court include the Sala Sahathai Samakhom (ศาลาสหทัยสมาคม), used for important receptions and meetings. The Sala Luk Khun Nai (ศาลาลูกขุนใน) is an office building housing various departments of the Royal Household. The main office of the Royal Institute of Thailand was also formerly located here. The Outer Court has a small museum called the Pavilion of Regalia, Royal Decorations and Coins. The Phimanchaisri Gate opens directly unto the Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall and is the main portal from the Outer Court into the Middle Court.[19][25]

Historically this court was referred to as Fai Na (ฝ่ายหน้า, literally In the front), and also served as the seat of the royal government, with various ministerial offices, a theatre, stables for the king's elephants, barracks for the royal guards, the royal mint and an arsenal. By 1925, all government agencies and workers had vacated the site and all of the buildings were converted for use by the Royal Household.[19]

Temple of the Emerald Buddha

[edit]

The Temple of the Emerald Buddha or Wat Phra Kaew (วัดพระแก้ว) (known formally as Wat Phra Si Rattana Satsadaram, วัดพระศรีรัตนศาสดาราม) is a royal chapel situated within the walls of the palace. Incorrectly referred to as a Buddhist temple, it is in fact a chapel; it has all the features of a temple except for living quarters for monks.[26] Built in 1783, the temple was constructed in accordance with ancient tradition dating back to Wat Mahathat, a royal chapel within the grounds of the royal palace at Sukhothai, and Wat Phra Si Sanphet at Ayutthaya. The famed Emerald Buddha is kept within the grounds of the temple.[5][27]

The temple is surrounded on four sides by a series of walled cloisters, with seven different gates. Like those ancient royal temples of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya, the Wat Phra Kaew complex is separated from the living quarters of the kings. Within these walls are buildings and structures for diverse purposes and of differing styles, reflecting the changing architecture during the various reigns of the kings. Despite this, most of the buildings within adhere strictly to classical Thai architecture. The establishment of the Temple of the Emerald Buddha dates to the very founding of the Grand Palace and Bangkok itself.[5][27]

Middle Court

[edit]The largest and most important court is the Middle Court or the Khet Phra Racha Than Chan Klang (เขตพระราชฐานชั้นกลาง) is situated in the central part of the Grand Palace, where the most important residential and state buildings are located. The court is considered the main part of the Grand Palace and is fronted by the Amornwithi Road, which cuts right across from east to west. The court is further divided into three groups of 'Throne halls' (Phra Thinang; พระที่นั่ง; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang) and one Siwalai Garden quarter.[28]

Phra Maha Monthien group

[edit]

The Phra Maha Monthien (พระมหามณเฑียร) group of buildings are located roughly at the centre of the Middle Court, therefore at the very heart of the Grand Palace itself. The traditional Thai style building group is enclosed by a low wall, as this was once the residential and sleeping abode of kings.[29] Thus it is considered the most important set of throne halls in the entire Grand Palace. All of the buildings within the Maha Monthien face north and are arranged from front to back with the public reception hall being at the front, ceremonial halls in the middle and residential halls at the back, all of them inter-connected to each other.[9][30]

All Royal coronations since that of King Rama II have taken place within the walls of this building group.[29] Construction began in 1785 at the order of King Rama I, the original buildings only included the Chakraphat Phimarn Throne Hall and the Phaisan Thaksin Throne Hall. Later King Rama II carried out major constructions including the Amarin Winitchai Throne Hall and other extensions. Later in his reign he added the Sanam Chan Pavilion and the Narai Chinese Pavilion. King Nangklao (Rama III) renamed the buildings from Chakraphat Phiman (meaning 'Abode of the Chakravartin') to Maha Monthien (meaning 'Great Royal Residence'). He carried out major renovations and spent most of his reign residing in these buildings. King Rama IV later added two arch-ways at the north and west side of the walls called the Thevaphibal and Thevetraksa Gate respectively. King Vajiravudh (Rama VI) added two portico extensions to eastern and western sides of the Amarin Winitchai Hall.[31] Since then most buildings in its original plan remain, with occasional renovations being made before important anniversaries such as the Bangkok Bicentennial Celebrations in 1982. Except for the Amarin Winitchai Throne Hall, the rest of the complex is closed to the public.[9][30]

The Thevaphibal Gate is the central entrance to the hall, however the central doorway is reserve exclusively for use by the king, others must enter through the two other doors on either side. The gate is guarded by Chinese-style statues, including mythical warriors and lions. The gate is topped by three Thai-style spires covered in Chinese ceramics.[29][32]

Phra Thinang Amarin Winitchai

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Amarin Winitchai Mahaisuraya Phiman (พระที่นั่งอมรินทรวินิจฉัยมไหสูรยพิมาน) or, in brief, the Phra Thinang Amarin Winitchai (พระที่นั่งอมรินทรวินิจฉัย) is the northernmost and forward building of the Maha Monthien buildings, It is also perhaps the most important. The throne hall was constructed in Thai style as a royal audience chamber, for receiving foreign ambassadors and for conducting important state businesses and ceremonies.[33][34]

The large throne hall stands on a 50 cm high base, the roof is covered in green and orange tiles. The pediment is decorated with a mural depicting the god Indra. The main central door is reserved for use by royalty, while others must enter through the adjacent side doors. Within the hall there are two rows of square columns, five on the left and six on the right, adorned with Thai floral designs. The coffered ceiling is decorated with glass mosaic stars.[33][34]

At the back of the hall is the Bussabok Mala Maha Chakraphat Phiman Throne (พระที่นั่งบุษบกมาลามหาจักรพรรดิพิมาน; RTGS: Butsabok Mala Maha Chakkraphat Phiman), flanked by two gilded seven tiered umbrellas. The throne is shaped like a boat with a spired pavilion (busabok) in the middle. This elevated pavilion represents Mount Meru, the centre of Buddhist and Hindu cosmology.[33] The throne is decorated with coloured enamels and stones as well as deva and garuda figures. The throne was once used for giving royal audiences.[34][35]

In the front of throne sits another, called the Phuttan Kanchanasinghat Throne (พระที่นั่งพุดตานกาญจนสิงหาสน์). The throne is topped by the massive Royal Nine-Tiered Umbrella, an important symbol of Thai kingship. The different tiers represents the king's power and prestige which extends in eight directions: the four cardinal directions and the four sub cardinal directions. The final and ninth tier represents the central direction descending into the earth. These giant umbrellas usually deposited above important royal thrones, and out of the seven of which are currently in Bangkok, six of these umbrellas are situated within the vicinity of the Grand Palace and another is situated above the throne within the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall of the Dusit Palace. The throne is made up of multi-layered squared platforms with a seat in the middle. The throne is used for the first royal audience of each king's reign and for annual birthday celebrations and other royal receptions. It was from this throne that King Rama II received John Crawfurd (the first British Envoy to Siam in almost 200 years) in 1821. Crawfurd was sent to Bangkok by the Governor-General of India Lord Hastings to negotiate a trade treaty.[32][34]

Phra Thinang Phaisan Thaksin

[edit]

Directly behind is the Phra Thinang Phaisan Thaksin (พระที่นั่งไพศาลทักษิณ). The rectangular-shaped hall is a ceremonial functions hall, where the most important religious and state ceremonies are held. It is the main venue where royal coronations are performed at the beginning of each king's reign, the last coronation ceremony held here was on 4 May 2019 for King Rama X. Formerly the hall was a private reception hall and living space of King Rama I. He often hosted meetings and dinners for his closest ministers and other trusted courtiers here. After his death the hall was converted into a ceremonial space. The long rectangular hall is decorated in rich murals depicting scenes from Buddhist and Hindu mythology.[36][37]

The hall houses two thrones. The Atthit Utumbhorn Raja Aarn Throne (พระที่นั่งอัฐทิศอุทุมพรราชอาสน์; RTGS: Attathit U-thumphon Ratcha At) or the Octagonal Throne is situated to the eastern part of the hall. This unusually shaped wooden throne is in the form of an octagonal prism and is decorated with golden lacquer, topped by a white seven-tiered umbrella. It is used during the first part of the Coronation ceremony, where the king is anointed with holy water, just prior to the crowning ceremony; all Chakri kings have gone through this ancient ritual. Once the king is anointed he is able to sit under the Royal Nine-Tiered Umbrella as a fully sovereign king.[37][38]

Across the hall to the western side is the Phatharabit Throne (พระที่นั่งภัทรบิฐ; RTGS: Phatthrabit). The throne is a chair with a footstool (more akin to its European counterparts) with two high tables to its sides. The throne is topped by another Royal Nine-Tiered Umbrella. This throne is used during the main part of the coronation ceremony, where the King is presented with the various objects, which make up the Royal Regalia. The king will crown himself, then be ceremonially presented with the objects of the regalia by the Royal Brahmins. These include: the Great Crown of Victory, the Sword of Victory, the Royal Staff, the Royal Flywhisk, the Royal Fan and the Royal Slippers.[37][39]

Apart from being the setting of these important ceremonies, the hall houses the Phra Siam Devadhiraj figure. This figure was created during the reign of King Rama IV to symbolise and embody the Kingdom (of Siam), its well-being and safety. It exists as the personification of the nation to be used as a palladium for worship. The golden figure depicts a standing deity, dressed in royal regalia, wearing a crown and holding a sword in its right hand. The figure is about 8 inches tall, and is housed in a Chinese-style cabinet in the middle of the Phaisan Thaksin Hall facing south. There are also other figures of the same scale depicting other Hindu gods and goddesses. The figure was once worshipped almost daily; today however religious ceremonies are only held to worship the figure during times of great crisis.[36][37]

Phra Thinang Chakraphat Phiman

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Chakraphat Phiman (พระที่นั่งจักรพรรดิพิมาน; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Chakkraphat Phiman) is situated behind the Phaisan Thaksin Throne Hall and is at the very centre of the Maha Monthien buildings. The hall was built during the reign of King Rama I as the primary apartment and sleeping quarter of the monarch, and is the inner most part of the Grand Palace.[36] The residential hall was formed out of three identical rectangular buildings, all inter-connected to each other. The middle section of the residential hall (out of the three), is a reception room while the other two sections, to the east and west, are divided into the personal apartments of the king. The east section is the primary bedchamber of the monarch; the hall is divided into two rooms by a golden screen. The northern room contains a canopied bed originally belonging to King Rama I; above this bed hangs a Royal Nine-tiered Umbrella. The southern room contains the dressing and privy chamber, above which hangs another Nine-tiered Umbrella. The west section was used as a multi-purpose hall for minor ceremonies and audiences; however in the reign of King Rama III the hall was converted into a bedroom. After his death it became the storage place for the various weapons and accoutrements of the monarch. The Royal Regalia of Thailand is kept here.[36][40]

When the Chakraphat Phiman Hall was first built it was entirely roofed with palm leaves; later these were replaced with ceramic tiles, then with glazed tiles during the reign of King Rama V. There is a tradition that no uncrowned kings are allowed to sleep within this hall. However once they were crowned they were required to sleep there, if only for a few nights, literally on the bed of their forefathers.[36][41] In 1910, prior to his coronation, King Rama VI had a well-concealed modern toilet installed near the bedchamber.[42] The king spent many nights here near the end of his life and died here in 1925. King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) and King Rama IX only spent a few nights here after their respective coronations in accordance with tradition.[36]

Between the Chakraphat Phiman and Phaisan Thaksin Halls is a small Front Reception Hall, where the king could receive courtiers while sitting on a small platform. There are two doors on either side of the platform leading into the royal apartments behind. To the rear and south of the Chakraphat Phiman Hall is the Back Reception Hall. This rear hall is flanked by two residential halls. These are reserved for members of the Royal Family and royal consorts from the Inner Court. They are called: Thepsathan Philat Hall (พระที่นั่งเทพสถานพิลาศ) (to the east) and the Thepassana Philai Hall (พระที่นั่งเทพอาสน์พิไล; RTGS: Theppha At Phailai) (to the west).[36][43]

Phra Thinang Dusidaphirom

[edit]

Apart from these grand state buildings, there are also several minor structures and pavilions surrounding the Phra Maha Monthien structures. These include four smaller halls at the sides of the Amarin Winitchai Throne hall.[44][45]

Aside the wall to the northwest is the Phra Thinang Dusidaphirom (พระที่นั่งดุสิตาภิรมย์; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Dusitaphirom). Built on a raised platform, the one-story hall was used as a robing chamber for the king when arriving and departing the palace either by palanquin or by elephant.[46] Hence the elephant-mounting platform to the west and a palanquin-mounting platform to the north. At first the structure was an open pavilion; the walls covered with rich murals were added later by King Rama III. The entrance is situated to the east and is lined with steps leading from the Amarin Winitchai Throne Hall. The hall is the only structure within the Grand Palace with exterior decorations. The golden lacquer and blue glass mosaic depicts angels carrying a sword.[44][47]

Phra Thinang Racharuedee

[edit]

To the southeast is the Phra Thinang Racharuedee (พระที่นั่งราชฤดี; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Ratcha Ruedi), a Thai-style pavilion constructed during the reign of King Rama VI as an outdoor audience chamber.[48] The pavilion was constructed for use especially during the birthday celebrations of the king. Originally King Rama IV had a two-story, European-style building constructed. Its purpose was to display gifts from foreign nations; however when this building became dilapidated King Rama V replaced it with a Chinese-style pavilion which was again dismantled and rebuilt. The present pavilion measures 12 by 7.80 metres (39.4 ft × 25.6 ft). The pediments are decorated with a gilded figures of Narayana on a garuda against a white mosaic background.[49][50]

Phra Thinang Sanam Chan

[edit]

The southwest structure is the Phra Thinang Sanam Chan (พระที่นั่งสนามจันทร์). Built during the reign of King Rama II, the pavilion is a traditional Thai pavilion with a raised platform inside.[51] King Rama II used the pavilion for relaxation and for sitting when supervising construction projects. Measuring only 3.30 by 4.50 metres (10.8 ft × 14.8 ft), the pavilion was portable and could be moved to different sites. The wooden pediments are decorated with gilded carvings and glass mosaic in a floral design with Chinese and Western influences. The eight columns are inlaid with glass mosaic. The inner platform is decorated with black lacquer and glass mosaic. The top of the platform is made out of a single panel of teak measuring 1.50 by 2 metres (4.9 ft × 6.6 ft). The pavilion was strengthened and given a marble base by King Rama IX in 1963.[44][52]

Ho Sastrakhom

[edit]To the northeast is the Ho Sastrakhom (หอศาสตราคม; RTGS: Ho Sattrakhom) or the Ho Phra Parit (หอพระปริตร), The hall is the same size as the Dusidaphirom Hall and the two appear to have been constructed concurrently. In accordance with ancient tradition, the hall was built for the use of Mon monks to create Holy water, which was then sprinkled around the palace ground every evening; this practice was discontinued during the reign of King Rama VII for financial reasons. Currently the ritual is only practiced during Buddhist holy days by Mon monks from Wat Chana Songkhram. The hall is divided into two rooms; the northern room is a prayer and ritual room for monks, including closets built into the walls for religious texts. The southern room is a storage room for Buddha images and religious artifacts.[53][54]

During times of war, the potency of weapons was enhanced by the holy water in a special ceremony. The weapons and special amulets were then distributed to soldiers before battle. As a result of this function the windows and doors of the hall are decorated with depictions of ancient weapons.[49][53]

Ho Suralai Phiman and Ho Phra That Monthien

[edit]

On each side of the Phaisan Thaksin Throne Hall is a Buddha image hall. On the east side is the Ho Suralai Phiman (หอพระสุราลัยพิมาน; RTGS: Ho Phra Suralai Phiman), which then connects to the Dusitsasada Gate. The Ho Suralai Phiman is a small Thai-style building which is attached to the Phaisan Thaksin Throne Hall through a short corridor. The hall houses important and valuable Buddha images and figures, including one representing each and every reign of the Chakri dynasty. Some relics of the Buddha are also reportedly kept here.[36][55]

The Ho Phra That Monthien (หอพระธาตุมณเฑียร) is located to the west side of the Phaisan Thaksin Hall and is also connected by a corridor in symmetry to the Suralai Phiman on the other side. The Phra That Montein hall contains several small gilded pagodas containing the ashes of Royal ancestors. Originally named Ho Phra Chao, the name was changed by King Rama II, who installed several valuable and ancient Buddha images in 1812. King Rama III and King Rama IV also have their own Buddha images installed here and carried out extensive renovations to the interior and exterior.[36][56]

Phra Thinang Chakri Maha Prasat group

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Chakri Maha Prasat buildings are composed of nine major and minor halls, structured in a similar scheme to the Maha Monthien Halls from north to south, however the two building groups contrasts greatly in styles. This group of palaces is situated at the centre, between the Maha Montein and Maha Prasat groups.[57] The whole of the Chakri Maha Prasat group was the work of King Rama V and foreign architects in the 19th century. During the reign of King Rama I the area was once an expansive garden, later named Suan Sai (สวนซ้าย) or 'Left Garden', the twin of Suan Khwa (สวนขวา) or right garden, now the Siwalai Gardens. The two gardens were named according to their location on the left and the right of the Maha Monthien buildings. During the reign of King Rama III a new residential pavilion called Phra Tamnak Tuek (พระตำหนักตึก) was constructed for his mother, Princess Mother Sri Sulalai. The new residence was composed of several low-lying buildings and pavilions. King Rama IV expanded the residence and gave it to his consort Queen Debsirindra. Within these buildings King Rama V was born (in 1853) and lived as a child.[58][59]

When King Rama V ascended the throne in 1868, he decided to build a new group of grander throne halls to replace the old structures. The first phase of construction began in 1868, then again in 1876, and the final phase between 1882 and 1887. King Rama V resided in the palace until 1910 when he gradually moved to the new Dusit Palace, to the north of the Grand Palace.[58] King Rama VI occasionally stayed in the palace; however he preferred his other residences in the country. By the reign of King Rama VII the buildings were in dire need of renovations, but due to economic constraints only the Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall was renovated. This work was carried out by Prince Itthithepsan Kritakara, an architectural graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Many of his works can still be seen today. During the reign of King Rama IX many of the buildings once more became so dilapidated that they needed to be demolished altogether. In their stead new halls were constructed in 2004 to replace them.[60][61]

Formerly the site hosted eleven different residential halls and pavilions; in 2012 only three are left, although they have been completely reconstructed: The Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall, the Moon Satharn Borom Ard Hall and the Sommuthi Thevaraj Uppabat Hall. Behind these structures lie the grand Borom Ratchasathit Mahoran Hall, which has been recently rebuilt. None of the rooms are open to the public, as state functions are still carried out within. The changing of the guards occurs at the front courtyard every two hours.[60]

Phra Thinang Chakri Maha Prasat

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Chakri Maha Prasat (พระที่นั่งจักรีมหาปราสาท; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Chakkri Maha Prasat) is situated on the northernmost part of the Phra Thinang Chakri group. The throne hall forms the front or the façade of the entire building group. In front of the throne hall is the Rathakit Field; on either side of the throne hall are the Phrom Sopha Gates. The throne hall is constructed in an eclectic style, a blend of Thai and European (more specifically Renaissance or Italianate) styles. The lower part of the structure is European, while the upper part is in Thai-styled green and orange tiled roofs and gilded spires or prasats.[62][63]

After a trip to Singapore and Java, in the East Indies (present day Indonesia) in 1875, King Rama V brought back with him two Englishmen, the architect John Clunich and his helper Henry C. Rose to design and construct the Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall.[57][64] Construction began on 7 May 1876. At first the King wanted an entirely European structure with domes. However at the insistence of Chao Phraya Si Suriyawongse (Chuang Bunnag), his Chief Minister, the King decided to add the gilded spires and Thai roofs. In 1878 the King personally supervised the raising of the final central spire of the building. The throne hall was completed in 1882, on the centenary of the House of Chakri and the Grand Palace. Thus the new throne hall was given the name Phra Thinang Chakri, meaning literally 'the seat of the Chakris'.[63][65]

The throne hall was constructed as part of a building group in a rotated 'H' shape plan, with two parallel buildings running on an east to west axis. In between is an intersecting hall, with an axis running north to south. The northerly end of the structure is the Chakri Maha Prasat Throne Hall; all other buildings are hidden behind it. The throne hall consists of three storeys, with three seven tiered prasats on each of the three major pavilions along the axis. The central pavilion with its portico and roof extensions is taller and larger than the other two on the sides.[63] Owing to a mix of Thai and European styles, the exterior decoration is a mixture of orders and does not follow strict classical lines. The Thai roofs are decorated with the same green and orange tiles as the other throne halls, in order for the new building to blend in harmoniously with the existing skyline. The external pediments and gates of the throne hall are decorated with the emblem of the Chakri dynasty, an intertwined Chakra and Trishula. Above the middle floor windows the western style coat of arms of Siam is used. On the semi-circular pediment of the central hall there is also a portrait of King Rama V.[66][67]

The incongruous make-up between the Western lower half and Thai roof has been compared with a Farang (Western) lady clothed in Victorian costume while wearing a Thai crown. The symbolism of this juxtaposition emphasises the superiority of Thai architecture (a crown upon the head) over that of the West (the lower half of the body).[68] This stylistic innovation was more than an artistic coincidence, as it was supposed to convey a significant political message of Siamese resistance to Western imperialism, both in terms of sovereignty and style. From another perspective, the building itself epitomizes the internal political struggle between the ideas of Westernization and modernity (led by King Rama V) and those of the traditional ruling elites (as espoused by some of his early ministers).[64][69]

Within the interior, the upper and middle floors are State floors; they are divided into several reception rooms, throne rooms and galleries, complete with royal portraits of every Chakri monarch (including Second King Pinklao) and their consorts. In the east gallery are Buddhist images and other religious images, while to the west are reception rooms for State guests and other foreign dignitaries. In other parts of the throne hall there are also libraries and rooms where the ashes of kings (Rama IV to Rama VIII) and their queens are housed.[62] Many of the European-made chandeliers inside the Hall initially belonged to Chao Phraya Si Suriyawongse; however they proved too big for his own residence and he eventually gave them to King Chulalongkron as gifts. The throne hall was also the first structure in Thailand in which electricity was installed, at the insistence of Prince Devavongse Varopakar. The lower floor or ground floor is reserved for servants and the Royal Guards. Currently there is also a museum displaying old weapons.[70][71]

Inside the main hall (throne room), situated at the very centre of the Chakri Maha Prasat Hall, is the Bhudthan Thom Throne (พระที่นั่งพุดตานถม; RTGS: Phuttan Thom), a chair on a raised platform. The Throne is flanked by two seven-tiered umbrellas, while the throne itself is topped by a Royal Nine-Tiered Umbrella. Behind the throne is a tapestry depicting a fiery intertwined chakra and trishula, or the 'Chakri', the emblem of the dynasty. The throne has been used by the king during important state occasions, such as the welcoming or accrediting of foreign diplomats and missions. The room itself has also been used by King Rama IX to welcome foreign dignitaries and heads of state, such as Queen Elizabeth II, President Bill Clinton and Pope John Paul II.[72] Recently the King welcomed more than 21 world leaders inside the room during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC Summit) held in Bangkok in 2003.[70] The wall of the throne room is decorated with four paintings depicting important scenes in the history of Thai foreign relations. On the east wall hang two paintings, titled 'Queen Victoria receiving King Mongkut's Ambassador' and 'King Louis XIV receiving the Ambassador of King Narai of Ayutthaya in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles'. On the west wall hang 'King Mongkut receiving British Envoy Sir John Bowring' and 'Napoleon III receiving the Siamese Ambassadors at Fontainbleau'.[73][74]

Phra Thinang Moon Satharn Borom Ard

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Moon Satharn Borom Ard (พระที่นั่งมูลสถานบรมอาสน์; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Mun Sathan Boromma At) is situated behind the Chakri Maha Prasat Hall to the east side and was built as a separate wing in 1869.[57] The hall encompasses the original area where King Rama V was born and had lived as a child. Previously King Rama I had the area set aside as a small mango tree garden. Currently the hall is set out as a small banqueting and reception venue.[58][75]

Phra Thinang Sommuthi Thevaraj Uppabat

[edit]The Phra Thinang Sommuthi Thevaraj Uppabat (พระที่นั่งสมมติเทวราชอุปบัติ; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Sommotti Thewarat Upabat) is situated on the opposite side of the Moon Santharn Borom Ard Hall, to the west of the Chakri Maha Prasat Hall. It was built in 1868.[57] The hall is divided into several state rooms for use by the king: there is a reception room and a council room. It was in this hall on 12 July 1874 that King Rama V stated to his ministers his intention to abolish slavery in Siam.[58][76]

Phra Thinang Borom Ratchasathit Mahoran

[edit]The Phra Thinang Borom Ratchasathit Mahoran (พระที่นั่งบรมราชสถิตยมโหฬาร; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Boromma Ratcha Sathit Maholan) is a large banquet hall at the very back of the Chakri Maha Prasat group. It was formerly the Damrong Sawad Ananwong Hall and the Niphatpong Thawornwichit Hall. The two halls were built by King Rama V as banqueting halls to host foreign guests and dignitaries. By the reign of King Rama IX, the building was so run down that the king ordered it to be demolished.[58] Construction of a new hall began in 1996, but was interrupted by the 1997 Asian financial crisis; it eventually resumed on 1 April 2004. The new throne hall was built on a raised platform and is composed of several interconnected buildings forming two internal courtyards. These rooms function as a new banqueting hall and are used for important state functions. On 13 June 2006, the hall welcomed the royal representatives of 25 monarchies worldwide for the celebration of King Rama IX's 60th Anniversary on the Throne. These guests included 12 ruling monarchs, 8 royal consorts and 7 crown princes.[77]

Phra Maha Prasat group

[edit]

The Phra Maha Prasat (พระมหาปราสาท) group of buildings is situated at the westernmost part of the Middle Court.[78] The main buildings within this area date from the reign of King Rama I and contain some of the oldest existing edifices within the Grand Palace. The entire throne hall group is contained within a walled and paved courtyard. Similarly to the other two groups, the Maha Prasat buildings were constructed, embellished and refurbished over successive kings' reigns. The buildings form a single axis from north to south, with the public throne hall to the front and residential halls behind. Surrounding them are lesser function halls and pavilions for use by the king and his court.[79][80]

After the construction of the Grand Palace, King Rama I ordered that a copy of the ancient Phra Thinang Sanphet Maha Prasat (พระที่นั่งสรรเพชญมหาปราสาท) should be built at the same site. The Hall was originally located at the old palace in Ayutthaya, which had been destroyed 15 years earlier.[11][12] This new throne hall was given the name Phra Thinang Amarinthara Pisek Maha Prasat (พระที่นั่งอมรินทราภิเษกมหาปราสาท; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Amarinthraphisek Maha Prasat). Construction began in 1782 and finished in 1784. This was the hall where King Rama I celebrated his full coronation ceremony. However, in 1789 the building was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground. In its place King Rama I ordered the construction of a new hall under a different design and name.[79][81]

As a result of this disaster, King Rama I predicted that the Chakri dynasty would last only 150 years from its foundation.[82] This prophecy was recorded in the diary of a contemporary princess; after reading it many years later, King Rama V remarked that 150 years was too short and that the princess must have inadvertently dropped a nought. The prophecy resurfaced in the minds of many people when only three months after the dynasty's 150th anniversary celebrations the Siamese revolution of 1932 occurred. The revolution replaced the absolute monarchy of the Chakri kings with a constitutional monarchy under Siam's first constitution.[83]

Two new halls were then built, the Dusit Maha Prasat and the Phiman Rattaya, each being designated for either ceremonial or residential use. Since then no coronations have been held inside. Upon the death of King Rama I, the hall was used for his official lying-in-state. It has since become a custom that the remains of kings, queens and other high-ranking members of the royal family are to be placed in the hall for an official mourning period.[79][81][84]

The entrance to this group of buildings is through one of the three gates at the northern end of the wall. These gates are decorated with Chinese porcelain in floral patterns. Only the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall is open to the public.[85]

Phra Thinang Dusit Maha Prasat

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Dusit Maha Prasat (พระที่นั่งดุสิตมหาปราสาท) dominates the Maha Prasat group. It was built on a symmetrical cruciform plan and the roof is topped with a tall gilded spire. The hall is considered an ideal example of traditional Thai architecture. Every aspect of its exterior decoration is imbued with symbolism. The hall is built in the shape of a tall mountain to represent Mount Meru, the mythological centre of the universe.[78][85]

The spire is divided into three sections. The base is formed of seven superimposed layers, each representing a level of heaven in accordance with the Traiphum Buddhist cosmology. The middle section is in the shape of a bell, flattened to create a four-sided shape. This represents the stupa in which the Buddha's ashes are interred. The top section is similar to the top of chedis, depicting a tapered lotus bud or crystal dew drop which signifies the escape from the Saṃsāra or cycle of rebirths. The spire is supported by garudas on each of its four sides; as well as being a symbol of kingship, the garuda represents the mythical creatures of the Himavanta forest surrounding Mount Meru.[81][85]

The pediments are decorated with the figure of Narayana, a Hindu deity, riding a garuda. This associates the king with Narayana and further signifies his authority. According to legend, Narayana descended from heaven in human form to alleviate the suffering of mankind. He represents all the qualities of an ideal king. The throne hall stands on a high base with convex and concave mouldings. The bottom layer, according to Thai beliefs, resembles a lion's paw; the lion is a symbol of the Buddha's family and alludes to the Buddha's own royal heritage.[78][86]

The most unusual feature of this throne hall is the small porch projecting from the front of the building. Under this porch stands the Busabok Mala Throne (พระที่นั่งบุษบกมาลา), whose spire echoes that of the hall itself. The high base of this throne is surrounded by figures of praying deities. During the reign of King Rama I, it was used when the king appeared before the representatives of his vassal states; later, it was used for certain ceremonies. The two doors to the hall are situated on each side of the throne.[78][86]

The interior walls of this throne hall are painted with a lotus bud design arranged in a geometric pattern. Praying deities sit within the buds, a common Thai motif often associated with holy places. The ceiling, which has a coffered octagonal section directly below the spire, is decorated with glass mosaic stars. This reinforces the impression of being in a heavenly abode. The interior panels of the door and window shutters depict standing deities facing each other, holding weapons as guards for the king. The thickness of the walls allows for the spaces between them and the shutters to be painted with murals depicting trees in Chinese style.[78][87]

The wings of the hall hold thrones for use in various royal functions; these include the Mother-of-Pearl Throne (พระแท่นราชบัลลังก์ประดับมุก) which stands almost at the centre of the hall, at the intersection of the four wings. This square throne, topped with a Royal Nine-tiered Umbrella,[87][88] is entirely inlaid with mother-of-pearl and dates from the reign of King Rama I. It was saved from the Amarinthara Pisek Maha Prasat when it burnt down in 1789.[12][78]

In the eastern transept is the Mother-of-Pearl Bed (พระแท่นบรรทมประดับมุก) which was made to match the Mother-of-Pearl Throne. It was once the king's personal bed and was kept inside the Phra Thinang Phiman Rattaya; once it was no longer used, it was transferred to its current location. The bed takes the form of a high platform with many layers and small steps leading to the top. When royal ceremonies are carried out within the hall, members of the royal family take their seats in the southern transept, while government officials sit to the north, Buddhist monks to the east; the funeral urn is to the west. At such times the throne and bed are used as altars for images of the Buddha.[87]

Behind the Mother-of-Pearl Throne is the Phra Banchon Busabok Mala Throne (พระบัญชรบุษบกมาลา; RTGS: Phra Banchon Butsabok Mala). This half throne protrudes from the southern wall of the throne hall and opens into it like a window. Its style is similar to the Busabok Mala Throne on the porch outside. It was made during the reign of King Rama IV, in order for the palace women to attend important ceremonies through the window but stay behind a screen, separating them from men arriving from the outside.[89]

Phra Thinang Phiman Rattaya

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Phiman Rattaya (พระที่นั่งพิมานรัตยา) is located directly behind the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall. It is a residential palace, built for King Rama I as his main royal apartment. Over time its use as such declined and eventually ended; now it is only used as a ceremonial venue. It was built in the traditional rectangular Thai style. The east, west and south sides of the hall are surrounded on the outside by a colonnade, and the building itself is surrounded by two gardens. During the reign of King Rama VI it was used as a meeting and function hall for members of the royal family. It also provided a venue for the investiture ceremonies whereby individuals are awarded with State orders and decorations by a member of the royal family. Currently the hall is only used, in conjunction with the Dusit Maha Prasat, as the main venue for state funerals.[85][90]

Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Aphorn Phimok Prasat (พระที่นั่งอาภรณ์ภิโมกข์ปราสาท; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Aphon Phimok Prasat) is an open pavilion, built on a platform at the east wall of the Maha Prasat group by King Rama IV; it was used both as a robing place for the king to change his regalia when entering the Maha Prasat, and also as the royal palanquin mounting platform. The pavilion is considered the epitome of the finest qualities of Thai traditional architecture in proportion, style and detail. A smaller replica was exhibited at the Brussels World Fair in 1958.[91][92]

The pavilion has a cruciform layout with the northern and southern ends being longer. The roof is topped with a spire of five tiers, making it a prasat rather than a 'maha prasat' (which has seven). The spire is supported by swans as opposed to the traditional garudas. The eastern pediment depicts the Hindu god Shiva standing on a plinth with one foot raised, holding a sword in his left hand and his right hand raised in blessing.[93] The columns of the pavilion are decorated with gold and silver glass mosaic in a floral pattern; the capitals of these columns take the form of long lotus petals.[89][92]

Phra Thinang Rachakaranya Sapha

[edit]The Phra Thinang Rachakaranya Sapha (พระที่นั่งราชกรัณยสภา; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Ratcha Karanyasapha) is located at the southern end of the eastern wall. A closed rectangular building, it was designed as a council chamber for use by the king and his ministers. In 1897, on his first trip to Europe, King Rama V installed Queen Saovabha Phongsri as regent, and she presided over privy council meetings here. In 1956 Queen Sirikit again presided over the privy council as regent while King Rama IX briefly entered the Sangha as a monk. The building is still used occasionally by the king for private audiences. Its projecting pediments over the roof line, common during the Ayutthaya period, are a notable feature.[94][95]

Ho Plueang Khrueang

[edit]

The Ho Plueang Khrueang (ศาลาเปลื้องเครื่อง) is a closed pavilion situated on the western wall of the Maha Prasat group. It was built by King Rama VI as a robing room. The building is a two-storied Thai style rectangular hall with a walkway leading from the top floor to the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall.[96]

Mount Kailasa

[edit]

A miniature model of Mount Kailasa (เขาไกรลาสจำลอง; RTGS: Khao Krailat Chamlong), the mythical abode of Shiva, was built during the reign of King Rama IV. It is crowned with a miniature palace on its summit, used as the setting for an important ceremony called the royal tonsure ceremony.[96] This ancient rite of passage would be performed for a prince or princess around the age of thirteen. Sometimes lasting seven days of festivities, the tonsure ceremony involved a purifying bath and the cutting of the traditional topknot hair of the royal child. The king himself cut the child's hair, which was later thrown into the Chao Phraya river as an offering.[97] The foot of the mountain is populated with statues of mythical animals from the Himavanta Forest. It is situated behind the walkway between the Dusit Maha Prasat Throne Hall and Ho Plueng Krueng. This area is considered part of the Inner Court and is not open to the public.[98]

Siwalai Garden

[edit]

The Siwalai Garden (สวนศิวาลัย, Suan Siwalai) is situated to the easternmost part of the Middle court and is considered separate from the other state buildings and throne halls. The garden has been in its present form, since King Rama V, and contains both royal residences and religious buildings. Throughout the years several structures were built and demolished by various kings. The garden was first created at the behest of King Rama I as a private retreat called the Suan Kaew (สวนแก้ว) or 'Crystal Garden'. The name was changed by Rama II to Suan Khwa or 'Right Garden', who also embellished the garden and transformed it into a pleasure garden for the inhabitants of the Inner Court.[99]

The greatest change to the area occurred during the reign of King Rama IV, when the entire garden was turned into a new residential palace. This palace was composed of several interconnected buildings of various styles and sizes for the king's use. This buildings complex was named the Phra Abhinaowas Niwet (พระอภิเนาว์นิเวศน์; RTGS: Phra Aphinao Niwet). The building group are on an east to west axis, with reception halls to the east and residential halls in the west. These buildings were built in a combination of Thai and Western styles; the principal building of the Phra Abhinaowas Niwet group was the Phra Thinang Ananta Samakhom; this European style grand audience chamber was used by the king to receive various foreign missions. Other buildings included King Rama IV's primary residential hall, observatory and banqueting hall. By the reign of King Rama V the Phra Abhinaowas Niwet building group became so dilapidated that most were eventually demolished; the names of some of the halls were later assumed by new royal buildings (for example the new Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall in the Dusit Palace). King Rama V had the area turned once more into a private garden for use by the Inner Court and also gave the garden its present name. The new garden contained some of the old buildings as well as new additions, such as a small lawn in the south western corner called the Suan Tao or 'Turtle Garden'.[100] The layout of the Siwalai Garden remained mostly unchanged until the present day.[101][102]

Phra Thinang Boromphiman

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Boromphiman (พระที่นั่งบรมพิมาน; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Boromma Phiman) is the largest structure within the Siwalai Garden; it is located at the northernmost end.[103][104] The two-storey Neo-Renaissance residence was constructed during the reign of King Rama V from 1897 to 1903. The new palace was built over the site of an old armoury, after King Rama V had it demolished. The new palace was intended as a gift to the first Crown Prince of Siam, Prince Maha Vajirunhis. It was originally named Phra Thinang Phanumart Chamroon (พระที่นั่งภานุมาศจำรูญ). However, before the construction was finished the prince died of typhoid at the age of 16. Once completed the palace was handed to the next heir, Crown Prince Maha Vajiravudh, who ascended the throne in 1910 as Rama VI. He later gave the palace its present name.[105][106]

Under the supervision of foreign architects, namely the German C. Sandreczki, the Boromphiman Throne Hall became the most modern building within the Grand Palace; it was also the first to be designed to accommodate carriages and motorcars.[107] The exterior walls are embellished with pilasters and elaborate plaster designs. The triangular and semi-circular pediments are decorated with stuccoed floral motifs. The palace's distinctive Mansard roof is covered in dark grey slate tiles. On the façade of the building, the main and central pediment show the emblem of the crown prince.[106][108]

Even though the architectural style and exterior decoration of the building is entirely Western, the interior decorations is entirely Thai.[103] The central hall, situated under a dome, is decorated with murals of the god Indra, Varuna, Agni and Yama—all depicted in Thai style. Below them are Thai inscriptions composed by King Rama VI himself.[106][109]

After his accession to the throne, King Rama VI occasionally stayed at the palace. King Rama VII stayed at the palace for a few nights before his coronation in 1925, while King Ananda Mahidol (Rama VIII) made the palace his main place of residence upon his return to Thailand from Switzerland in December 1945. He lived in this palace with his younger brother Prince Bhumibol Adulyadej (later King Rama IX) and his mother Princess Sri Sangwan. On the morning of 9 June 1946 the palace bore witness to his mysterious and unexplained death by gunshot.[103][110] King Rama IX later refurbished the palace and added an extra wing extending south.[101][106]

Currently the palace is not open to the public, and serves as the official guest house for visiting Heads of State and their entourage.[104][108][111] To the southeast of the Boromphiman Throne Hall, there are also two guest houses for use by the entourage of state visitors.[106]

Phra Thinang Mahisorn Prasat

[edit]The Phra Thinang Mahisorn Prasat (พระที่นั่งมหิศรปราสาท) is a small pavilion built on the wall between the Siwalai Garden and the Maha Monthien buildings. The pavilion has a mondop-style roof and a gilded spire, decorated in glass mosaic. The pavilion was built by King Rama IV as a monument to his father King Rama II. After its completion the ashes of King Rama II was moved and was housed in the pavilion. After the death of King Rama IV the ashes was moved back to the Ho Phra That Monthien Buddha Image Hall, currently the pavilion houses several Buddha images.[112][113]

Phra Thinang Siwalai Maha Prasat

[edit]The Phra Thinang Siwalai Maha Prasat (พระที่นั่งศิวาลัยมหาปราสาท) is located on the southern-eastern end of the Siwalai Garden.[101][114] The Siwalai Maha Prasat is a Thai-style edifice with a Mondop style spire of seven tiers. Built during the reign of King Rama V in 1878 to house the metal statues of his four predecessors, which were cast in 1869. The hall was to be used as a royal pantheon, where the lives of previous monarchs were to be commemorated and worshiped.[115] Later King Rama VI had the statues removed and rehoused at the Prasat Phra Thep Bidorn in the Temple of the Emerald Buddha compound, where they would be more accessible to the public. On 6 April 1918 the first ceremony of worship was inaugurated, this ceremony continues to be performed annually. Since the removal of the statues, the Siwalai Maha Prasat has been left vacant.[116]

Phra Thinang Sitalaphirom

[edit]The Phra Thinang Sitalaphirom (พระที่นั่งสีตลาภิรมย์) is a small open pavilion made of wood, built by King Rama VI. The pavilion is situated on the northern edge of the lawn south of the Boromphiman palace. The pavilion is decorated with a flame motif in gilded black lacquer. The gables bear the insignia of King Rama VI. The king used the pavilion as a place of rest and as a seat during garden parties.[101]

Phra Buddha Rattanasathan

[edit]The Phra Buddha Rattanasathan (พระพุทธรัตนสถาน) is a Phra ubosot (or ordination hall), situated at the very centre of the Siwalai Garden. The religious building is a shrine to a Buddha image called the Phra Buddha Butsayarat Chakraphat Pimlom Maneemai (พระพุทธบุษยรัตน์จักรพรรดิพิมลมณีมัย; RTGS: Phra Phuttha Butsayarat Chakkraphat Phimon Manimai) which was brought from Champasak in Laos.[citation needed] The ubosot was built for this purpose by King Rama IV. The ubosot is built of grey stone and has a two-tier green title roof. At the front there is a portico of pillars. Running around the outside of the ubosot is an open pillared gallery. Religious ceremonies have been performed here in the past.[101][117]

Inner Court

[edit]

The Inner Court or the Khet Phra Racha Than Chan Nai (เขตพระราชฐานชั้นใน), referred to simply as Fai Nai (ฝ่ายใน; RTGS: Fai Nai; literally 'The Inside'), occupies the southernmost part of the Grand Palace complex. This area is reserved exclusively for use by the king and his harem of queens and consorts (minor wives). These women were often called 'forbidden women' or Nang harm (นางห้าม; RTGS: nang ham) by the general populace. Other inhabitants of the court were the king's children and a multitude of ladies-in-waiting and servants. The king's royal consorts were drawn from the ranks of the Siamese: royalty and nobility. Usually there were also the daughters of rulers of tributary states.[83][118] Royal polygamy ended in practice during the reign of King Rama VI, who refused to keep a polygamous household. It was ended officially by King Rama VII in the early 20th century, when he outlawed the practice for all and took only one consort: Queen Rambhai Barni. By this time the inhabitants of the court had dwindled to only a few and finally disappeared within a few decades afterwards.[42][119] Historically the Inner Court was a town complete within itself, divided by narrow streets and lawns. It had its own shops, government, schools, warehouses, laws and law courts, all exclusively controlled by women for the royal women. Men on special repair work and doctors were admitted only under the watchful eyes of its female guards. The king's sons were permitted to live inside until they reached puberty; after their tonsure ceremonies they were sent outside the palace for further education.[42] There are currently no inhabitants within the Inner Court and the buildings within are not used for any purpose; nevertheless, the entire court is closed to the public.[120]

The population of the Inner Court varied over different periods, but by all accounts it was large.[121] Each queen consort had her own household of around 200 to 300 women. Her various ladies-in-waiting were usually recruited from noble families; others were minor princesses who would also have a retinue of servants. Each minor wife or consort (เจ้าจอม; Chao Chom) had a fairly large household; this would increase significantly if she gave birth to the king's child, as she would be elevated to the rank of consort mother (เจ้าจอมมารดา; Chao Chom Manda). Each royal lady had a separate establishment, the size of which was in proportion to her rank and status in accordance with palace law. Altogether the population of the Inner Court numbered nearly 3,000 inhabitants.[122]

The Inner Court was once populated by small low-lying structures surrounded by gardens, lawns and ponds. Over the course of the late 19th century new residential houses were constructed in this space, resulting in overcrowded conditions. Most of the buildings that remain were constructed during the reign of King Rama V in Western styles, mostly Italianate.[123] The residences vary in size and are divided into three categories; small royal villas or Phra Thamnak (พระตำหนัก; RTGS: phra tamnak), villas or Thamnak (ตำหนัก; RTGS: tamnak) and houses or Ruen (เรือน; RTGS: ruean). Each was distributed to the inhabitants in accordance with their rank and stature. The court is surrounded and separated from the rest of the Grand Palace by a second set of walls within, parallel to those that ring around the palace as a whole. These walls are punctuated by a set of gates that connects the Middle the Inner Courts to the outside and to each other; the entrance through these gates were strictly monitored.[124] The three main building groups in the Middle Court are built so that the residential halls of each are situated to the south and straddled the boundary between the Middle and Inner Court. Thus these residential spaces of the king became the focal point of palace life and the lives of the palace women on the inside.[125] Immediately behind these residential halls are the large royal villas of high-ranking consorts such as Queen Sukhumala Marasri and Queen Savang Vadhana. Surrounding them are smaller villas belonging to other consorts such as those belonging to Princess Consort Dara Rasmi. Finally at the lower end (the southernmost part) are the row houses or Tao Teng (แถวเต๊ง; RTGS: thaeo teng) for the middle- and low-ranking consorts.[123] These residences also functioned as a de facto secondary layer of surveillance, at the very edges of the Inner Court.[126]

The Inner Court was governed by a series of laws known as the Palace Laws (กฎมนเทียรบาล, Kot Monthien Ban; literally 'Palace Maintenance Law'). Some of the laws dated back to the times of the Kingdom of Ayutthaya. Most of them deal with the hierarchy and status of the women, while others deal with their behaviour and conduct.[127] The order and discipline of the inhabitants were enforced by a regiment of all-female guards (กรมโขลน, Krom Klone; RTGS: kromma khlon). These guards were described by Prince Chula Chakrabongse as "tough looking amazons".[42] The head of this body was known as the Atibodi Fai Nai (อธิบดีฝ่ายใน; RTGS: Athibodi Fai Nai) the directress of the inside, under her command were various officials. These officials had specific responsibilities concerning every facet of life within the Inner Court. These responsibilities included duties concerning: discipline and jails, the maintenance of Buddhist images, the guarding of gates, the inner treasury and expenditure. One of their main duties was to accompany men, once they were admitted into the area, and to remain with them until they left. They controlled the traffic of the court and were drilled like regular soldiers. When any person of importance passed along the streets they ran ahead and cleared the way for them. At night they patrolled the streets with lamps or torches.[121] Misbehaviour or indiscretion on behalf of the wives was punishable by death, for the women and the man.[128] The last such punishment was met out in 1859 to a young nobleman and a minor wife, who were having an affair.[129]

Only the children of the king could be born inside the Inner Court. Every detail of the birth of the royal child was recorded, including the time of birth, which was to be used later by court astrologers to cast his or her horoscope. Ceremonies concerning the birth and the rites of passage of the child were performed within the walls of the Inner Court. The birth of a royal child was first announced by a succession of women who proclaimed the news along the Inner Court's streets. There were two waiting orchestras, one on the inside made of women and one on the outside of men, who would then carry out the official proclamation with conch shell fanfares. If the child was a prince the Gong of Victory was to be struck three times. The children would live with their respective mothers and be educated in special schools within the court.[128]

Although the women of 'The Inside' could never have the same level of freedom to those on the outside, life inside the Inner Court was not disagreeable, as life was easier than the outside and most necessities were provided for. The women usually entered the palace as girls and remained inside for the rest of their lives. As girls they would be assigned certain duties as pages; as they grew older and became wives and mothers they would have a household to look after. During the reign of King Rama IV, the women of the palace were for the first time allowed to leave; however they were required to obtain permission from the directoress first and were strictly chaperoned.[124] Malcolm A. Smith, physician to Queen Saovabha Phongsri from 1914 to 1919, wrote that, "there is no evidence to show that they longed for freedom or were unhappy in their surroundings. Even Mrs. Leonowens, fanatical opponent of polygamy that she was, does not tell us that".[130] Indeed, Anna Leonowens' book The English Governess at the Siamese Court, published in 1873, was set inside the Inner Court.

Defensive walls

[edit]The castellated walls of the Grand Palace were constructed during the reign of King Rama I in 1782. Later during the reign of King Rama II the Grand Palace and its walls were extended towards the south. Cannon emplacements were replaced with guard houses and were given rhyming names. The northern wall measures 410 metres, the east 510 metres, the south 360 metres and the west 630 metres, a total of 1,910 metres (6,270 ft). There are 12 gates in the outer walls. Inside the palace, there were over 22 gates and a labyrinth of inner walls; however some of these have already been demolished. Around the outer walls there are also 17 small forts. On the eastern wall, facing Sanamchai Road, there are two throne halls.[5][15]

Pavilions

[edit]Phra Thinang Chai Chumpol

[edit]

The Phra Thinang Chai Chumpol (พระที่นั่งไชยชุมพล; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Chai Chumphon) is located on the north of the eastern wall, opposite the Temple of the Emerald Buddha. The small rectangular pavilion was built on the top of the wall of the palace. The pavilion has a roof of two tiers and is covered with grey tiles.[131] The exterior is decorated with black lacquer and glass mosaic. The pavilion was built by King Rama IV as a viewing platform, where he could observe royal and religious processions going by along the Sanamchai Road. The pavilion was also used for a time as the main shrine of the Phra Siam Thevathiraj figure, before it was moved to its current shrine in the Phaisan Thaksin Hall.[132]

Phra Thinang Suthaisawan Prasat

[edit]

Situated on the south eastern wall of the Grand Palace is the Phra Thinang Suthaisawan Prasat (พระที่นั่งสุทไธสวรรยปราสาท); the hall sits between the Deva Phitak and Sakdi Chaisit Gates on the eastern wall.[101][133] It was first built by King Rama I in imitation of the "Phra Thinang Chakrawat Phaichayont" (พระที่นั่งจักรวรรดิ์ไพชยนต์; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Chakkrawat Phaichayon) on the walls of the Royal Palace in Ayutthaya. Originally called the Plubpla Sung or high pavilion, it was made entirely of wood and was an open-air structure. During the reign of King Rama III, a new structure was built out of brick and mortar. This new structure was renamed Phra Thinang Sutthasawan (พระที่นั่งสุทไธสวรรย์; RTGS: Phra Thi Nang Sutthai Sawan). The hall is used by the king to give audiences to the public and view military parades.[131][134]

The new structure consists of two-stories, the lower in Western style and the top level in Thai design. The central pavilion has a wooden balcony, which is used by the king and royal family for the granting of public audiences. The roof over the central pavilion is topped by a five-tier prasat in Mondop style, decorated in glass mosaic. The hall's wings stretching from the north to the south, each has nine large windows along the exterior. Later in the reign of King Rama V, the entire structure was refurbished and finally given its present name.[101][134]

Gates

[edit]

The Grand Palace has twelve gates (ประตู, Pratu, literally a door), three along each of the four walls. These massive gates are built of brick and mortar and are topped with a Prang style spire. These gates are all painted in white, with gigantic red doors. Each of these outer gates were given rhyming names, starting from the north west in a clockwise direction around.[15][135]

- North wall

- East wall

- South wall

- West wall

Forts

[edit]Along the walls of the Grand Palace there are seventeen forts (ป้อม, Pom); originally there were only ten, with later additions made. These small structures are usually small battlements with cannon placements and watchtower. The forts were also given rhyming names.[15][18][135]

- North wall

- East wall

- Sanchorn Jaiwing (ป้อมสัญจรใจวิง; RTGS: Sanchon Chai Wing)

- Sing Kornkan (ป้อมสิงขรขันฑ์; RTGS: Singkhon Khan)

- Kayan Yingyut (ป้อมขยันยิงยุทธ; RTGS: Khayan Ying Yut)

- Rithi Rukromrun (ป้อมฤทธิรุดโรมรัน; RTGS: Ritthi Rut Rom Ran)

- Ananda Kiri (ป้อมอนันตคีรี; RTGS: Ananta Khiri)

- Manee Prakarn (ป้อมมณีปราการ; RTGS: Mani Prakan) (corner fort)

- South wall

- West wall

Museum of the Emerald Buddha Temple

[edit]

The Museum of the Emerald Buddha Temple (พิพิธภัณฑ์วัดพระศรีรัตนศาสดาราม), despite its name, is the main artefacts repository of both the Grand Palace and Temple of the Emerald Buddha complex. The museum is located between the Outer and Middle Court and sits opposite the Phra Thinang Maha Prasat Group. A building was constructed on the present location in 1857 during the reign of King Rama IV as the Royal Mint (โรงกษาปณ์สิทธิการ, Rong Kasarp Sitthikarn; RTGS: Rong Kasap Sitthikan). King Rama V ordered the mint to be enlarged, but not long after this the building was destroyed by fire and needed to be rebuilt.[136][137]

The two-story structure is rectangular in shape. The portico has four Ionic columns with fluted stems and cabbage leaf capitals. The front gables of the building have Renaissance style plaster moulding. The lower part of the exterior walls are made of plastered brick. The upper windows have semi-circular French windows, with pilasters on both sides.[137] In 1902 a new royal mint department was constructed outside the palace's walls and the old mint building was left vacant. The building was then first converted for use as a royal guards barracks and later as a royal guards officer's club.[136][137]

In 1982, on the bicentennial anniversary year of the founding of Bangkok and the building of the Grand Palace, the building was selected as the site of a new museum. It was established at the instigation of Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn to hold certain architectural elements, which had to be replaced; various artefacts and Buddha images that were donated to the Grand Palace by the general public.[136][137]

The ground floor of the museum displays a varied selection of artefacts.[136] These included certain architectural elements, which were removed from various buildings within the Grand Palace during different renovations, as well as were the stone Buddha images and Chinese statues. They included many figures from Thai literature, the Ramakien, such as Suvannamaccha and Hanuman. The stone figures date from the reign of King Rama III, and were later moved to the museum to prevent damage.[137] In the central hall are the bones of white elephants. These elephants were not actually white but have certain special characteristics such as pinkish colouring and cream eyes. The White elephant was an important symbol of kingship; the more the monarch possessed the greater was his prestige. This belief and veneration of the animal is common to many other South-east Asian cultures.[138][139]

The upper floor rooms display more artistic and precious objects. In the main hall are two architectural models of the Grand Palace, the first representing the Grand Palace during the reign of King Rama I, and another in the reign of King Rama V. Behind these are numerous Buddha images and commemorative coins. In the doorway leading to the main hall is a small mother-of-pearl seating platform known as Phra Thaen Song Sabai (พระแท่นทรงสบาย), which was once located in the Phra Thinang Phiman Rattaya Throne Hall. The platform was used for informal audiences and dates from the time of King Rama I.[138] At the end of the main hall stands the Phra Thaen Manangsila Throne (พระแท่นมนังคศิลาอาสน์; RTGS: Phra Thaen Manangkha Sila At), which is believed to date to the Sukhothai Kingdom and was brought back to Bangkok, from Sukhothai, by King Rama IV, when he was still a monk. Against the walls on either side of the hall are four different Buddha images of Javanese style; they were purchased by King Rama V. The room to the right of the Manangsila Throne displays the various seasonal robes of the Emerald Buddha. To the left of the main hall is a lacquer ware screen depicting the crowning of Shiva, king of the gods. The screen was formerly kept in the Phra Thinang Amarinthara Pisek Maha Prasat; it was saved from the fire apparently by the hands of King Rama I himself. The rest of the upper floor displays various objets d′art (such as a model of Mount Kailasa) and more Buddha images.[140]

See also

[edit]- Associated

- Other royal palaces in Bangkok

- Dusit Palace – Main royal residence from around 1899 to 1950

- Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall- Main residence of the current monarch since 2016

- Chitralada Royal Villa – Main residence of the monarch from around 1950 to 2016

- Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall

- Abhisek Dusit Throne Hall

- Vimanmek Palace

- Phaya Thai Palace – Main residence of the monarch from around 1909 to 1910

- Related subjects

- List of Thai royal residences

- Rattanakosin Kingdom

- Chakri dynasty

- Monarchy of Thailand

- Coronation of the Thai monarch

- Thai art

- Architecture of Thailand

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Thailand's king given full control of crown property". Reuters. 17 July 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ "Crown Property Act 2018" (PDF) (in Thai). Royal Thai Government Gazette. 2 November 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Royal Institute of Thailand. (2011). How to read and how to write. (20th Edition). Bangkok: Royal Institute of Thailand. ISBN 978-974-349-384-3.

- ^ "Grand Palace among world's 50 most visited tourist attractions". Royal Thai Embassy, Washington D.C. Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 16 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Hongvivat 2003, p. 7

- ^ a b c d Suksri 1999, p. 11

- ^ a b c Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 18

- ^ Rod-ari, Melody (January 2016). "Beyond the Ashes: The Making of Bangkok as the Capital City of Siam". Political Landscapes of Capital Cities. pp. 155–179. doi:10.5876/9781607324690.c004. ISBN 978-1-60732-469-0.

- ^ a b c Quaritch Wales 1931, p. 71

- ^ a b Chakrabongse 1960, p. 90

- ^ a b Garnier 2004, p. 42

- ^ a b c Chakrabongse 1960, p. 93

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 19

- ^ Suksri 1999, p. 15

- ^ a b c d e f Suksri 1999, p. 16

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 21

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 24

- ^ a b Hongvivat 2003, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Suksri 1999, p. 17

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 26

- ^ พระบรมมหาราชวัง at the Thai Wikipedia (Thai).

- ^ Suksri 1999, p. 7

- ^ a b c Suksri 1999, p. 8

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 29

- ^ Watcharothai, et al. 2005, p. 197

- ^ Garnier 2004, p. 43