Awdal: Difference between revisions

→Environmental protection: minor spacing fix Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Removed dubious source to accurately reflect prevailing scholarship on demographics of the region Tags: Reverted Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 467: | Line 467: | ||

| url-status = live |

| url-status = live |

||

| df = dmy-all |

| df = dmy-all |

||

}}</ref> |

|||

}}</ref> Aswell as the [[Habar Awal]] subclan of the larger [[isaaq]] clan along the coast in Lughaya district <ref>{{cite book |last1=Roland |first1=Marchal |title=Studies on Governance |date=1997 |publisher=United Nations Development Office for Somalia, 1997 - Awdal (Somalia) |page=Awdal region Page 9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gny1xwEACAAJ}}</ref> However, most sources show that the Isaaq do not inhabit the Awdal Region.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Ambroso, G (2002)|title=Pastoral society and transnational refugees:population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia 1988 - 2000 |url=https://www.unhcr.org/sites/default/files/legacy-pdf/3d5d0f3a4.pdf|page=5|quote= Main sub-clan(s) Habr Awal, Region(s): Waqooyi Galbeed, Main districts: Gabiley, Hargeisa, Berbera. Main sub-clan(s) Gadabursi, Region(s): Awdal, Main districts: Borama, Baki, part. Gabiley, Zeila, Lughaya.}}.</ref><ref name="digitalcommons.macalester.edu">Samatar, Abdi I. (2001) "Somali Reconstruction and Local Initiative: Amoud University," {{URL|1=http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/bildhaan/vol1/iss1/9|2=Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies: Vol. 1, Article 9}}, p. 132.</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Battera |first1=Federico |others=Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.) |title=Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=z4AAAwAAQBAJ&q=gadabuursi+awdal&pg=PA296|access-date=18 March 2010 |year=2005 |publisher=I.B. Taurus |location=London |isbn=1-85043-634-7 |page=296 |chapter=Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Pos3wAofV4UC&pg=PA278 |quote=Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans. The Gadaabursi are concentrated in Awdal.}}</ref><ref>UN (1999) Somaliland: Update to SML26165.E of 14 February 1997 on the situation in Zeila, including who is controlling it, whether there is fighting in the area, and whether refugees are returning. "Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs." p. 5.</ref><ref>{{Cite book | last1=Renders | first1=Marleen | last2=Terlinden | first2=Ulf | title=Negotiating Statehood: Dynamics of Power and Domination in Africa |chapter=Chapter 9: Negotiating Statehood in a Hybrid Political Order: The Case of Somaliland |editor=Tobias Hagmann |editor2=Didier Péclard |url=http://asia-abdulkadir.de/docs/RendersTerlinden2010.pdf|page=191|access-date=2012-01-21|quote="Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security."}}</ref> |

|||

== Districts == |

== Districts == |

||

Revision as of 20:13, 3 January 2024

Awdal

| |

|---|---|

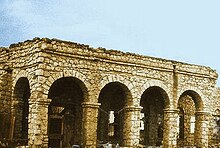

Ruins of the Muslim Sultanate of Adal in Zeila | |

| Motto(s): | |

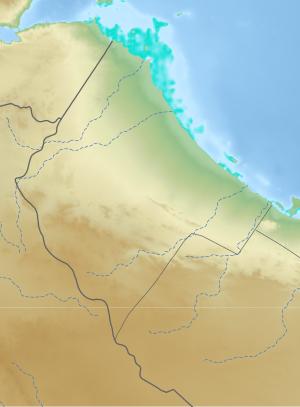

Location in Somaliland | |

| Coordinates: 10°48′3″N 43°21′7″E / 10.80083°N 43.35194°E | |

| Country | |

| Administrative centre | Borama |

| Government | |

| • Type | Regional |

| • Governor | Hassan Dahir Haddi[1] |

| Area | |

• Total | 21,374 km2 (8,253 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,136 m (7,008 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 2,632 m (8,635 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (2022[2]) | |

• Total | 576,543 |

| • Density | 27/km2 (70/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

| Area code | +252 |

| ISO 3166 code | SO-AW |

| HDI (2021) | 0.401[3] low · 3rd |

Awdal (Template:Lang-so, Template:Lang-ar) is an administrative region (gobol)[4][5] in western Somaliland. It was separated from Woqooyi Galbeed and became a province in 1984 and is the most northwesterly province of Somaliland. To the east it borders Maroodi Jeex and Sahil; to its north-west it borders Djibouti; to its south and south-west lies Ethiopia; and the Gulf of Aden to its north.[6] The province has an estimated population of 1,010,566.[7] The region comprises the four districts of Borama, the regional capital, Baki, Lughaya, and Zeila.

Overview

Awdal (أودل) takes its name from the medieval Adal Sultanate (عَدَل), which was originally centered on Zeila.[8] The area along the Ethiopian border is abundant with ruined cities, which were described by the British explorer Richard F. Burton.[9]

Topographical

Arabian plate

Awdal region is three distinct topographical zones: the coastal, mountainous and plateau (Ogo) zones. Starting from the north along the sea is the coastal zone. The coastal zone comprises sandy plains that stretches from Sahil region in the east to Djibouti in north- west and extends up to 70-90 kilometers from the sea and is about 600 meters above the sea level. Next to the coastal zone is the mountainous zone. Geologically, much of the Awdal region is located in the Arabian Plate.[10]

Mountainous zone

The mountainous zone consist a string of mountains, known as Golis range, extends from east to west all across the region and is about 700 –1000 meters above the sea level. The zone is characterized by topographical features such as deep gorges, valleys, and dry water courses, with and without springs, that all end up into coastal zone. During rainy season, the water courses carrying rain water run-offs from mountains go into the sea. The run-offs washed down good soil from mountain tops and, in the process, cause environmental degradation and deterioration of roads passing across the mountains into coastal towns; they also leave behind deep sandy soils in coastal plains that make road transportation a big challenge. The last and the third topographical feature of the region, next to the Mountainous Zone in the south, is the Ogo Plateau zone. It about 1100–1300 meters above the sea level. Most of the major towns and villages including the regional capital, Borama occur in this zone and has high population density in the region.[11]

Economic

The major economic activities of the region are pastoralists, agro-pastoralists, fishing and trade.[12] The major economic activity of the people in coastal zone is pastoralist that rear camels, sheep and goats. Traditional fishing and small scale commercial activities are the major economic activities of the people in the coastal towns of Lughaya and Zeila. There are also thriving business activities in Zeila and the border town of Loya-addo. Most of the coastal towns are thinly populated especially during the summer season as the temperature of the coastal zone becomes brutally hotter (about 45 degrees Celsius) and people move up into the cooler Mountainous zone. Unlike the coastal zone, the economic activities of the Mountainous Zone are agro-pastoralists that rear livestock and irrigation farming activity. Pastoralists of the mountainous zone are famous for goats since goats are adaptable to the topographical features of the zone. Irrigated farming is new to the zone and was introduced in the 1980s as cooperatives by former socialist regime. After the fall of the socialist regime the cooperatives members divided the cooperative farms among themselves followed by individual land grabbing for farming. The farms occur along the banks of togs (dry water courses). Farmers use shallow wells and running water springs for irrigation and grow crops such as fruits and vegetables for cash to supplement livestock keeping. The major economic activities of third zone (Ogo Zone) are agro-pastoralist and commerce. Agro-pastoralists are sedentary cultivators of rain-fed farm that farming with livestock keeping. The zone gets the more rain during the rainy season and rain-fed farmers grow sorghum, maize and finger millet and keep small number of cattle, sheep and goats. Besides agro-pastoralist, commerce is another major economic activity in the zone. There is a thriving commercial activity in major towns and villages in the zone that enables people to have an easy access to essential goods and services. There is also vibrant cross-border trade between Ethiopia and Awdal Region.[13]

Education

Currently[when?][14] P.16, there are 87 primary and secondary schools in Awdal region. These schools can be divided into three main categories: public primary and secondary schools, private primary and secondary schools and Religious schools. Somali is the medium of instruction in public primary schools and Arabic and English as second languages. English is used as medium of instruction both public and private secondary schools. The private schools use different types of curricula in both primary and secondary schools Religious schools; on the other hand, teach recitation of Koran and Arabic. The establishment of Amoud University in 1998 stimulated expansion of schools and increase of student enrollments in both public and private s primary and secondary schools in the city. Multiplication of primary and secondary schools has increased not only in the city but also in other Somaliland regions as many universities were opened in other regions as well.

Before establishment of the university, almost all schools existing in the region were religious schools sponsored by Islamic charity organizations. These schools were owned and run by local religious scholars. Some of these religious schools were teaching exclusively the recitation of the Holy Koran while others were teaching curricula borrowed from Arab countries and used Arabic as medium of instruction. A very few of the most successful students were sent to Arab countries to further their religious studies. The myth that only a government could have the capacity of creating universities had vanished and many other universities were established by private individuals and groups in other regions. The following table shows the number of primary and secondary schools, student population, and gender distributions in the region.[15]

| Table 1: Primary and Secondary Schools enrolment in 2012/2013 School Year | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| School level | No. of schools | Enrolled Students | Totals | |||||||

| Primary | 79 | 27,189 | 710 | |||||||

| Secondary | 8 | 6,092 | 150 | |||||||

| Total | 87 | 33,281 | 860 | |||||||

According to the Ministry of Education,[16] the 79 primary schools in the region consist 569 classrooms of which 369 are elementary level and 227 classrooms intermediate level. In total 710 teachers work in primary schools of whom only 307 are in the payroll of the ministry of education while the rest are working on voluntary basis and represent 56.76% of the total primary school teachers. It understandable the impact this could have on the performance of unpaid teachers and the administration. On the other hand, there are 8 secondary schools in the region that consist 71 classrooms. In total 150 teachers currently work in the secondary schools. Despite the increase of total student population in the region, still many school age children are not attending schools at all and render petty services such shoe shining, car cleaning, and dish washing in urban areas so as to contribute to daily subsistence of their families. Most of these children come from impoverished families that could not afford to send their children to school. The private schools have their own weaknesses as well: overcrowded classrooms; absence of sport facilities; work with curricula different from the one developed for Somaliland primary and secondary schools; and charges high tuition fees.

Health development sector

According to the Ministry of Planning, the population of Awdal Region is estimated in between 540,000 and 570,000. The health staffs of the region in the government payroll are 275. Most of the health services are supported by UN agencies and international organizations such as WHO, UNICEF, COOPI, Merlin, World Vision, Caritas, and PSI.[17][unreliable source?][18]

| Table 2: Number and categories of health staff | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade A | Grade B | Grade C | Grade D | Total | ||||||

| Staff number | 70 | 100 | 82 | 43 | 295 | |||||

Most of health staff is concentrated in Borama. Health facilities in remote districts and villages do not have sufficient staff with adequate training. And, most of the Grade A staff which comprises doctors and qualified nurses are based in Borama town and in major villages of Borama district.

| Table 3: Distribution of Health facilities in the region | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Borama | Baki | Lughaya | Zeila | Total | |||||

| MCHs | 48 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 87 | |||||

| Mobile Teams | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | |||||

| Hospitals | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||

| Health Posts | 60 | 19 | 14 | 17 | 110 | |||||

EPI activities in 2016

- 1. Routine Activities 95 MCHs Including Mobile team

- 2. None Routine Activities 4 MCHs

- 3. Two Rounds of CHDs

- 4. Two Rounds of NIDs

- 5. Immunization Out-Reach Activities Done by SRCS for 8 months in Borama Districts including Dilla, 3 fixed team and 5 mobile teams.

- 6. Immunization Out Reach Activities Done by WVI for 3 months in Baki and Lughaya District for 4 teams

- 7. No Out Reach Activities done in Zeila District

Malaria activities in 2012

- 1. IRS is done in 5 villages.

- 2. ITNs distribution to two villages.

- 3. RDTs and Malaria Kits distributed all MCHs and Health Posts.[18]

Labor and social affairs sector

The regional health authority[19] estimated that the population of the region is in between 540,000 and 1,010,566. Referring to World Bank Survey in 2002, Ministry of Planning (Somaliland) five-year National Development Plan (NDP) 2012–2016, estimated Somaliland working age group between 15 and 64 years old. This constitutes 56.4% of the total population of Somaliland. Building on these facts, the working population in Awdal Region could be in between 225,600 and 246,975.6. According to Somaliland NDP, total employment among economically active Somaliland population is estimated at 38.5% for urban and 52.6 for rural and nomadic. Thus, total urban and rural and nomadic employment population of the region could be estimated at 86,856 and 133, 781 respectively which is equivalent to 21.71% and 33.4% respectively as well. Consequently, the regional unemployment rate is in between 66.6% and 78.29% respectively. Despite these figures, there is general perception that unemployment rate in the region is much higher than the aforementioned percentages. The mass emigration of youth in the region is mainly associated with the absence of employment opportunities. Most of the emigrating youth is university graduates. Parents of these emigrating youth expend their savings and/or properties with the all associated risks of emigration. There is a wide spread poverty in the region as reported by regional representative of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs. This was associated, besides unemployment, with the prolonged droughts, crop failures, environmental degradation, and internal displacements. Vulnerable groups such as children, elderly people, and lactating and pregnant mothers are mostly affected. The Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs aims to avert social ills such poverty, illiteracy, caring the elderly and handicaps, and protection of vulnerable groups such women and child; and above all creation of employment opportunities for the active age groups.[20]

Youth and sports sector

There is not a specific statistical figure for youth population in the region.[21] However, according to 2012 – 2105 Somaliland National Development Plan of Ministry of National Planning and Development (2011), young population below the ages of 30 constitute between 60 – 70 percent of the population of the country. Youth is the future of the society and warrant development of their potentialities. To realize their potentialities, employment opportunities has to be created for them; recreation facilities established; practical technical and entrepreneurial trainings provided;political participation of youth encouraged ; and the traditional mind- set of parents and/or elders of dealing with their otherwise grown up sons and daughters as "children" has to be averted. Without rectifying the above-mentioned dreadful constrains, our youth is susceptible to anti-social ills practices and behaviors such as drug addiction, gang mentality, dependency, mental illnesses, and risky emigration to overseas. One of the main sector challenges identified was the difficulty of obtaining new playgrounds. Since the collapse of Somali regime in 1991, public lands were grabbed and claimed by individuals. New playgrounds could only be acquired through purchases or donations. Without obtaining funds for acquisitions of new playgrounds and for the restoration and improvement of existing playgrounds, youth would have an ample idle time to plunge into anti social habits.

There are two playgrounds in the Borama city: Haji Dahir Stadium and Xaaslay Stadium. There is also the Hanoonita basketball centre.[20]

Religion and endowment sector

Somalis have been Muslims for more than a thousand years and belonged to the Sunni branch of Islam.[22] In addition to customary laws, Islamic laws were practiced in all judicial and social matters. Since the Socialist military regime took power in 1969, the roles of religion in both social and legal affairs were minimal and suppressed.

Since the collapse of the Socialist State of Somalia in 1991, Islamic practices have taken a new turn. People have become more religious than before and traditional moderate Somali culimos (Islamic Scholar) have been replaced by young men educated in religious schools in the Arab world. They have come with money and with different strands of Islamic practices, costumes and teachings. They have opened their own modern religious schools (madarases); built their own mosques; changed the traditional attire of Somali women; and disapproved of the ways in which the traditional culimos used to preach and spread Islamic standards among the population.

The new young Islamic educators, unlike the traditional culimos, have established their own Sharia courts to adjudicate social disputes, inheritance matters, and even business-related issues. They have not only taken over the religious matters of Somali people but also the business sector, and make up the most successful business community in Somaliland and the Somali region.

The Somaliland constitution enshrines Islam as the state religion and the laws of the nation are built on Islamic Sharia. The Ministry of Endowment and Islamic Affairs is mandated to promote and preserve Islamic principles and values as well as render some social services. The ministry has devolved its mandate to regions and districts. However, devolution of the services of the ministry into the regions and districts has yet to take effect. Its roles are mostly assumed by private religious individual and groups. The absence of institutional capacity hampers services in the sector in the region.[23]

Economic development

Agriculture development sector

Agriculture[24] is the second largest economic activity in Awdal Region besides livestock rearing. According to regional agriculture authority, 35% of the population in region depends on agriculture. Two main types of agriculture activities are practiced in the region: Rain-fed and irrigated farming. The lands under cultivation in the region are estimated at 40,000 hectares of rain-fed farming and 4,000 hectares are irrigation farming respectively. Rain-fed activities are practiced on the southern part of the region along the Ethiopian border, locally known as Ogo Zone (plateau), during the rainy season between the months of April and September. Irrigated-farming is practiced in central mountainous zone of the region between the coastal plains in the north and Ogo Zone in the south. Most of the irrigated-farms occur along the banks dry rivers beds. Some of river beds have running streams and farmers and irrigate the farms on gravitation while dug shallow-wells in dry river beds and diesel driven water pumps.

According to regional agriculture authority, 8,000 families are involved in rain-fed farming activities in the region. Rain-farmers are agro-pastoralists. They grow cereal crops such as sorghum, maize, and other cereals such as finger-millet, and at the same time keep livestock such cattle, sheep and goats and camels in small numbers. Both the farm and animal productions are mainly used for family subsistence and any extra production is taken to urban centers for sale to generate some cash to buy other essential goods and services. Irrigated-farms, on the other hand, support 2000 families in the region. Like rain-fed farming irrigated farming practices are for subsistence as well. Farmers grow fruits and vegetables for cash and grow tomatoes, lettuce, guava, oranges, papaya, lime, watermelons, melons (Shamam) pepper, carrot, onions etc. They take them to local urban centers and generate cash to buy food stuffs and other essential goods and services. The Supply irrigated farms is very high and flood local markets during rainy seasons. The supply of the fruits and vegetables are very limited and very expensive during the dry season. Refrigeration would have been possible if cheap energy were available. Agriculture sector plays a major role in the economy of the region. It provides employment opportunities to many people in rural and urban areas; supports the livelihoods of more than 35% of the regional population; and contribute the local food production of the country. In spite of these roles, 22.73% of total cultivable land is utilized and the current production level of the land already under cultivation is low. This can be attributed to: inappropriate farming practices, depletion of soil fertility, inadequate agriculture extension services; distribution of free grains from international organizations; rural-urban migration of manpower; poor or absence of feeder roads; and lack of financing sources.[25]

Livestock development sector

Livestock is a mainstay of Somaliland economy. More than 60% of the population depends directly or indirectly on livestock products and by-products for livelihood.[26] It provides employment opportunities; generates a bulk of central and local government revenues; a source of hard currency needed for doing business with outside world such as importing goods and services; and is the main sources of milk and meat for both urban and rural population of the country. Like other regions of Somaliland, livestock rearing is largely pastoral. Pastoralists are nomadic and move with their livestock on a seasonal basis looking pasture and water. They mostly keep large stocks of sheep and goats, camels and some cattle. They are mostly found in all the three topographical zones of the region: Ogo (Plateau), Mountainous, and Coastal. In mountainous zone pastoralists keep large stocks of goats and sheep and lesser stocks of camels, and cattle due to the harsh terrain of the zone which is mainly suitable for goats. Pastoralists in the coastal zone keep large stocks of camels, sheep and goats. The coastal zone is 500 to 600 meters above the sea level and the terrain is flat and has good pastures for all types of livestock when its receives adequate rains which are infrequent and erratic. Agro-pastoralists are sedentary communities that mix both farming and livestock rearing practices. Most of regional agro-pastoralists are found in the plateau (Ogo) zone which is 1200–1300 meters above the sea level. Agro-pastoralists cultivate sorghum and maize crops and keep lesser stocks of cattle and sheep and goats than the nomadic pastoralists as a supplement to farm crops. Remains of the grown crops are used for fodder for farm animals. The head office of sector in the regions is in Borama and consists of two technical departments and an administration and finance department. The technical departments are: Animal Health and Animal Production. The Animal Health department is responsible for livestock diseases, vector control and laboratory services. Animal Production department is responsible for livestock production related services (these need total restructuring). The ministry has also small offices in other districts in the region. Most veterinary services are carried out by mobile teams comprising public and private professionals mostly sponsored by international agencies.

| Table 6: Livestock population in the region ( estimated in thousands) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Goats and Sheep | 800-1000 | ||||||||

| 02 | Camels | 100-200 | ||||||||

| 03 | Cattle | 25-30 | ||||||||

| Total | 925-1230 | |||||||||

Notwithstanding the economic importance of livestock in the region, the sector is facing major challenges. First, many of the traditional livestock grazing lands are turned into regular farmlands. And, consequently, the regular seasonal movements of pastoralists for alternate pasture lands are severely curtailed. This adversely affected livestock population and production quality. Without a regional rural land management policy and demarcation between grazing and farmlands, the economic roles of the livestock is in jeopardy.[citation needed]

- Second, available skilled livestock health professionals are very limited. The number of skilled staff in the region is 17. This number is too small to meet regional demand. During livestock mass treatments and vaccinations, additional skilled staff such Community Animal Health Workers (CAHWs) are hired from outside.[citation needed]

- Third, livestock health facilities in the region are also very limited. The only one existing in the region is in Borama. The sector office in Borama is both an administration offices, and regional drug store. Two other small vet facilities exist in Dilla and Quljeed districts and used as offices and drug stores.[citation needed]

- Fourth, the institutional capacity of the ministry of livestock in the region is weak. There are no administration offices, livestock health facilities, and adequate skilled professional in Baki, Lughaya and Zeila districts where livestock population in the region is mostly available.[citation needed]

- Finally, the regional ministry is severely constrained by the absence of regular budget allocations. Lack of adequate budget allocations hinders operational activities of the sector.[citation needed]

Fisheries development sector

Awdal is the third region that has the longest coastline in Somaliland.[27] The coast is about 300 km long from Sahil Region in the east and Republic of Djibouti in the west. The two districts of Lughaya and Zeila are coastal towns in the region and are respectively the capital cities of the two districts. With the exception of a few fishers in the coastal towns, most of the people in Lughaya and Zeila districts are pastoralists that rear camels, sheep and goats in the coastal plains. Pastoralists depend on their animals for living and despise fishing as the livelihood of impoverished people that has no livestock of their own. Despite the vast marine resources available, as indicated in Somaliland National Development Plan, fishing plays a very limited role in the economy of coastal towns. This attributed to many factories. [citation needed]

- First the demand for fish consumption is very low in the coastal

towns due to limited population densities, and as result of this, a very small number of artisan fishermen are engaged in subsistence type of fishing and use small boats just to feed their families and meet the available market.

- Second, the coastal towns have no easy access to major urban centers where demand for fish consumption is high. The fishing communities in coastal towns of Zeila and Lughaya are separated from major towns in the region by sandy coastal plains which stretch more than 60 70 km from the sea and more than 120 km from east to west. Trucks frequently break in sandy roads and cause a lot of repairs and maintenance to owners. Behind sandy coastal plains in the south, transportation in the mountainous zone, with deep gorges, valleys and dry river beds cutting deep in the zone, is very difficult and risky. The mountainous zone stretches east to west and in not less than 70 km from coastal plains. These topographical features of both zones severely discourage truck owners and, as a result, cause very high transportation charges and long travel duration. Together, the sandy coastal plains and mountainous features make market accessibility almost impossible of transporting fish from coastal towns to major urban centers since most of Somaliland's major urban centers are in Ogo Zone which occurs south of both of coastal and mountainous zones.

- Third, large scale of fishing is hampered by absence of constant ice-making and fish storage facilities; lack of organization and skills in repairing and maintenance services of fishing boats and fishing gear; high fuel costs; and above all lack of freezer trucks to transport fish to major urban centers where demand for fish is very high. Demand for fish has become higher since the livestock export ban was lifted in 2009. The price of meat has almost quadrupled since 2009.

- Fourth, both Zeila and Lughaya occur on straight coastline without natural shelter, absence of fishing ports (jetty) and landing sites. Consequently, fishing boats are exposed to open sea with all its turbulent winds and waves.

- Finally, the sector is constrained by the absence of institutional capacity including ice-making and fish storage facilities in coastal towns. Besides, availability of fishing gear, spare parts and lack of fishing gear repairs and maintenance skills are major bottlenecks of the fishing industry in the region.

Industry and commerce sector

Since the collapse of socialist regime,[28] the numbers and the scope businesses enterprises have spread dramatically like a bush fire. Most of them are owned and managed by family members although some of them are co-owned by group of individuals. Most of them are involved in different types commercial activities such retailing, wholesaling, service provision. Manufacturing industries is very limited and mostly depend on imported raw materials According to their capital base, enterprises in the region can roughly be divided into three main categories or levels: low, medium, and upper. The low capital level categories include petty trading activities solely established to generate daily subsistence for their owner-managers and are not in the real sense of the word profit-oriented. Their capital base varies from less than a hundred dollar to several hundred US dollars and can be classified as survival businesses. They are mostly dominated by female and a few male individuals and have no shop centers and are run in open air. The medium level enterprises have more capital bases than the low levels. Their capital base varies from several thousand to several tens of thousands of US dollars. Most of them are family owned or co-owned and managed by a group of individuals, have shop centers, licensed, involved in provisions of goods and services. The upper-level enterprises have more capital base than the other two levels. Their capital is estimated to several hundred thousands of US dollars. They are a few in numbers and are involved in either service sector such as remittance, merchandising, import-export trading, or run small scale manufacturing industries. All three levels provide different types of employment opportunities from self-employment to paid jobs and enabled the public to have easy access to essential goods and services. Despite the sector plays an important role in the economy of the region, it is constrained by, first, absence of financial institutions for financing existing and potential business opportunities. Second, lack proximate port facilities in the coastal towns of Lughaya and Zeila cause high transportation cost of imported commodities. Third, lack affordable energy discourages potential investment opportunities. Finally, the institutional capacity of the sector to provide necessary technical support services is missing.

Mining

The mining sector is the least developed in the region. The only mining activity in the region is gemstones.[29] Many people are involved in mining gemstones in a very primitive manner. Stones such as emerald, sapphire, and aquamarine are mined in the mountainous part (Golis Range) of the region. People use crude tools for mining which cause unnecessary wastage, effort, and costs. Most of the limited production of gemstones have cracks and are rarely marketable. The qualities of gemstones depend upon the depth, equipment employed and professional skills utilized for excavation. Even the method of identifying the exact site to mine gemstones is very precarious. Prospective miners use a hit-and-miss method to locate excavation sites.

Gemstone mining generates a limited but unreliable income for the miners. Very few individuals buy stones from the miners and take to unreliable outside markets. Nobody knows the exact price of gemstones at external markets. It takes months to produce a hundred grams of gemstone and the amount of effort and money expended on its excavation often exceeds the income generated.

Another challenge is that the groups involved in the mining of gemstones are not formally organized as business entities. Some individuals work together, sharing effort and costs, and equally any income generated. There are frequent conflicts, mismanagement, and theft among the groups.

Planning and development

The regional Ministry of Ministry of Planning (Somaliland)[30] is responsible for the implementation of national development policy in the region. The mandate of the ministry includes:

• Collection and analysis of data and other relevant information in collaboration with the regional offices and other sectors.

• Establishing Regional development oversight committee.

• Ensuring the implementation and supervision of a three-year regional development plan of sectors.

• Registration of LNGOs working in the region and coordinating their development activities.

• Coordination of the regional development activities of international and local organizations according to the regional development plan.

Environment

Environmental protection

Awdal Environment Protection Region,[31] has three distinct topographical zones. Starting from the north along the sea is coastal zone which stretches from Sahil region in the east to Republic of Djibouti in North West. The coastal zone comprises sandy coastal plains that stretch up 70 km south into mountainous zone, otherwise known Golis range, which is about 500–1000 meters above the sea level.

The coastal zone is brutally hot, sometimes more than 45-degree Celsius, during the summer, from May to September, and receives lesser rain than other zones in the region. This zone is locally known "Guban" which means "burned" in English and its dwellers are called "Qorax-joog" (Sun dwellers). The coastal zone usually gets its rain during the winter season when other zones are in dry season. Known locally as Hais", the rainy season is usually from December to January. Because of its low rainfall, the vegetation in coastal plains consists of different types of grasses and a few hardy scattered acacia trees. All dry rivers from mountainous zone end up in coastal plains and during the rainy season runs -offs from mountainous zone end up in the low coastal plains and bring alluvial soil. A colonial governor from Zeila travelled along the coastal zone in 1887 and described the rich vegetations and heavy forests along the banks of dry rivers in the coastal plains, some of which with running streams. He also wrote about the rich vegetation and the presence of wild animals such as elephants, antelopes, lions, leopards, black panthers, and different types of birds.

Next coastal zone in the south is the Mountainous Zone otherwise known Golis. The mountainous zone is 600 to 1000 meters above the sea level and gets Gu‟ rains during the months of April to September. Some areas of this zone adjacent to coastal areas also get some of winter (Hais) rains received by the coastal zone. Because of this, the zone gets more rains than the coastal zone, and has, as a result, more vegetation. The zone is also characterized by the existence of many dry rivers with running water streams throughout the year. There had been thick forests in the valleys and along banks of the river beds that had been a conducive environment for various wild animals such as lions, kudu, Oryx, leopards, cheetah, mountain dik-dik (Ala-kud), Gazelles and even elephants. It is said that the last elephant in Somaliland has died in the 1940s in Dibirawein Valley, now in Baki District, and some of its bones are still sitting there. However, since the 1970s, almost all valleys and banks of the dry rivers with running streams were turned into irrigated farms and, in the process, the thick forests were cleared, burned for charcoal and/or used for construction purposes and, consequently, the wild animals hunted, killed or migrated as their habitats completely were devastated by human intrusion. People in this zone were pastoralists and reared goats and sheep and a few camels. With the introduction of farming, the livestock population has also declined as the wild animals.

The third topographical zone in the region is the Ogo Zone which runs parallel next to Mountainous Zone in the south. It is an upland terrain (plateau) which is about 1100 to 1300 meters above the sea level and gets more rain during the Gu‟ Season. Most of the people in this zone are sedentary agro-pastoralists that mix cultivation of cereals crops in rain-fed farms with livestock keeping in small cattle numbers such as cattle, sheep, and goats. The Ogo Zone is densely populated and suffered the worst environmental degradation.

Understanding the fragility of the Somaliland environment, the colonial administrations introduced parks, reserved grazing lands, and established forestry camps in the region. There had been three such sites in Borama, Jir-jir, Libaaxley, and Baki which were reserved for wildlife and livestock grazing. The reserved lands were closed off during the rainy seasons and solely opened for livestock grazing during the dry season when pastures become scarce. The reserves were not only reserved for livestock pastures but for wild animals as well. Forester camps were also established for the protection wild animals and for maintenance of wildlife habitats.

For the last 40 years, the environment has been vast deteriorating and sustaining some irreversible damages. Many factors have contributed to such environmental degradation. As population density has increased and economic conditions become harsh, people turned to natural resources such as forests for a living. Moreover, the socialist regime of Siyad Barre has introduced cooperative farming practices, and, as a result, many common grazing lands and valleys and that were the breeding environment of wildlife, were given to specific people in the name of farming cooperatives. Furthermore, the situation of the environment deteriorated further during the civil wars when law and order collapsed following the fall of the socialist regime. Afterwards, an unprecedented land grabbing started in rural areas. Forests were cleared for farms, burned for charcoal, cut down for construction materials and for living as well.

As reported by the Baki District Commissioner, charcoal business is causing unprecedented environmental destruction in Baki District. Every day about 15 trucks carrying hundreds of tones of charcoal head off for Borama, Gebilay, Hargeisa, and Zeila towns. More than 700 men are involved in charcoal burning activities and have established camps in all well-wooded areas of the district. As indicated in NDP of Somaliland government, there is an urgent need for formulation of sound national environment protection policy and establishment of an effective environmental management mechanism in order to achieve a sustainable national and subnational development.

Infrastructure

Roads sector

Roads are very crucial for the movement of people and goods.[32] Because of the topographical features of the region, road transport is an impediment to development of the region. The topographical features of the region make road transport very discouraging: sandy coastal plains and range of mountains. Coastal plains are very sandy and a lot of dry rivers from mountains zone pass through coastal plains and have been depositing sands for centuries. The distance of coastal plains from east to west is estimated at 200 km and the distance between the mountainous zone and coastal zone is estimated at 70 km. It takes about 3 to 4 hours for a truck to travel from Lughaya to Zeila which is about 150 km apart due to sandy plains and sandy dry river beds. During rainy seasons transport movement stops for days. Besides, the distance between Zeila and Borama is about 250 km and it takes about 8 hours for a truck to travel between the two towns due to the poor condition of the road.

The coastal and mountainous zones are indeed economically very potential but are the least developed so far. Absence of serviceable inter-regional roads networks and feeders roads are the main challenges to the development of fisheries, agriculture, and mining sectors. According to the Chinese proverb, poverty can be easily reduced through building roads: if you want fight poverty build a road. When roads are opened to impoverished isolated communities life could dramatically improve.

Public works, housing, and transport

The regional Ministry of Public Works,[33] Housing and Transport has had the mandate of providing guidance and oversight over public works, transport, and housing in all districts of the region. However, the sector is scarcely operational.

Since the collapse of the late Siyad Barre regime in 1990, most of the public buildings in all districts are occupied by IDPs and/or refugee returnees. Still others are in utter disrepair. There had been a total of 64 of public offices and houses in the region (40 in Borama, 12 in Baki and 12 in Lughaya). Even the head office of the sector in Borama is occupied by IDPs. The vehicle garages and workshops are also occupied. The head office of the sector in the region has neither the capacity nor the resources required for the restoration of sector operations. The regional head office of the sector theoretically comprises six functional departments:

- 1. Transport

- 2. Construction

- 3. Architecture

- 4. Planning

- 5. Government Houses

- 6. Administration & Finance

Formally each of the six departments is supposed to have five technical staff members. There are only 10 staff people in the region including a security guard at the present, and they share two available offices. Other districts do not have administration offices, nor other essential sector infrastructure.

Energy Sector (Borama Electricity)

Energy is very crucial for the development of a nation. However, the achievements of Somaliland‟s development goals depend upon the availability of cheap energy sources. Energy is indispensable for industrial, household, transportation uses. In Somaliland, the main sources of energy are fossil fuels. They include diesel, petrol, kerosene, charcoal, and fire wood. They are utilized for generation of electricity, transport and for household use. With the exception of charcoal and firewood, all the others are imported from outside and huge amounts of hard currency is expended on their importation. Like other regions, charcoal and fire woods are the main fuel sources utilized for household, businesses and other institutions that are involved in food services in the region. Charcoal consumption is the highest in the urban centers while firewood is mainly used in rural areas. Charcoal and firewood fuels have had utter deforestation in the region. Borama town used to have an electricity power station known as Borama Power Station. It was established just before the Socialist Regime came into power in 1969. It was used for lighting public houses and the main streets of the town. The station was expanded in the 1980s by Henley on Thames (UK) a sister city of Borama. Henley on Thames provided two electricity generators of 1500 KVAs each and their spare parts and accessories awaiting installation. After the collapse of the Socialist Regime in 1990, private individuals joined together and took over the power station and had been providing electricity for fee up to 2003. Eventually, the Borama Power Station collapsed for mismanagement and distribution infrastructures such as overhead wires and poles are now being used by private electricity companies created right after the collapse of the power station. Now, the Borama Power Station building and compound are idle. Currently, more than three private companies provide electricity in Borama. The many attempts of forming public-private partnership (PPP) with private companies by Borama Municipality, representing Borama Power Station, ended in vain. The private electricity companies charges $1.20/watt. And, as result of this, electricity is only used for lighting households and for minor commercial operations purposes.

Civil Aviation Sector

Borama Airport,[34] which is 2 km long and 200 meters wide, was constructed in 1988 by former collapsed socialist government. The purpose the airport was built was to enable the region to have an access to air transport for the movement of goods and people and link the region to the outside world. Current operations of the airport are very limited. Most of passenger, cargo planes and UN aircraft use Hargeisa and Berbera airports due to appropriate airport facilities and services. Moreover, the airport runway is unpaved and rough and its land demarcation is not yet fixed by the local government. Thus, the airport area is being frequently infringed by land grabbers. The airport has no security fence and, consequently, exposed to roaming livestock. Besides, due to absence of the fence, truck drivers use the runway as road and pose unnecessary risks to aircraft. Additionally, the airport is missing some very essential services and facilities such weather forecasting services, fire trucks, air communication and water supply system. Lack of institutional capacities such shortage of trained staff, budgetary restrictions and lack of transport are some of the constraints hampering Borama Airport operations. If the above challenges are duly addressed, airport operation would probably resume operations.

Information and Culture Sector

Awdal[35] Region does not have both public and private radio stations. However, people listen to Radio Hargeisa since 2012 when its capacity was expended to Short Wave which transmits its programs in Somali, English, Amharic and Arabic from 8:30 am to 11:00 am and from 1:00 pm to 11:00 pm. Besides, BBC and VOA FM radios also broadcast programs in Somali, Arabic and English. There is one privately owned TV station (Rayo TV) in Borama, and is viewed on normal antenna in Borama Township. However, people in the region also view Somaliland National TV and Somaliland Space Channel which are viewed both on normal antenna and via satellite respectively. Other privately owned satellite dishes include Hargeisa Cable TV. Both government and privately owned TVs have representatives in the region. Other Medias widely used by educated people are websites and local daily newspapers. They provide news, advertisements and other diverse information on to the users. There are no daily local newspapers published in the region. However, more than 10 daily local newspapers are published in Hargeisa and are sent via road transport and usually arrive in the region in afternoons. All of the newspapers have field reports in the region.

Posts and Telecommunication Sector

The regional head office of the Posts and Telecommunication Sector is in very bad shape and could not be restored. The Post Office was built during the colonial administration with mud bricks and was mainly used for postal services. It sits on an area of not more than 10 square meters. The successive governments did not add anything to it. Since the collapse of the Somali government, the small building was occupied by IDP family for some time and badly destroyed it. The Post office building is now in utter destruction. The head of the sector in region described as the "home of bats and rats". Even the land surrounding the post office, including its front compound are taken and built by intruders Currently, the total employees of the sector in the region are 7. They are all based in Borama and have no office spaces. They carry around with office documents and their salaries paid through the private money transfer agencies at the end of every month. The sector challenges are not specific to the region with the exception of office premises. It shares with other regions in terms of priorities and strategies as indicated in the Somaliland NDP. What is missing and urgent is the establishment of office premises in all districts of the regions.

Water Sector

The topographical features of the region determine categories of water sources. The region can be divided into three distinct topographical zones: coastal, mountainous, and plateau (Ogo).

Starting from the northern part of the region along the sea is the coastal zone which is about 500 to 700 meters above the sea level. The coastal zone comprises sandy plains that extend from 70 to 90 km from sea. This zone is very hot with temperatures of about 40-degree Celsius during the summer season (June- August). Ease of access to reliable water sources is important in summer for both people and livestock. In the rainy season, water can be obtained from hand-dug shallow wells in dry rivers beds, but these dry up as soon as rains stop or the sun gets hotter. As a result of this, the only reliable water sources in the coastal zones are strategically placed bore wells both for human and livestock consumption.

Of the eight bore wells in the region, 6 are in the coastal zone [citation needed]. According to a regional water officer, the bore wells El-gal, and Laanta Morohda are in Zeila district; and Karure and Kalowle are in Lughaya District. Two more bore wells are Husayn and Gerissa. Kalowle bore well provides water to pastoralists and Lughaya Town which is about 8 km from the bore well site. UNICEF has drilled a backup strategic bore well at the site in case the old bore well breaks down. Karure bore well does not have a backup yet. These bore wells are strategic in the sense that they are drilled in the driest areas of the coastal zone, where water sources are not obtainable. However, the bore wells have no backups and if a bore well breaks down, the live of both livestock and the people are at great risk.

Zeila town gets its water from a bore well near Tokoshi, a village about 8 km west of Zeila town. The bore well does not provide sufficient water and its water turns salty in the dry season. Since Zeila occurs in the coastal zone, it is very hot during the summer season and life is difficult without adequate water supply. Besides, Zeila is the entry point of people and goods coming from Republic Djibouti and, as a result of this, there is a customs office where the Ministry of Finance collects import taxes from goods entering the country. Accordingly, the provision of sufficient and drinkable water supply is very crucial for lives of town people and for the movement of people between Somaliland and Republic of Djibouti.

The mountainous zone consists of a string of mountains that extend east to west, south of the coastal zone. The zone has many dry river beds and valleys between the mountains. The river beds provide permanent water in terms of springs and shallow wells dug in the dry river beds. Besides human and livestock consumption, the water sources are used for the irrigation of fruit and vegetable farms. Unlike the other zones of the region, the Mountainous zone has reliable water sources in the region.

The Ogo Zone is an upland terrain which runs along the south of the mountainous zone. It is about 1000–1300 meters above the sea level. The main water sources of this zone are man-made rain water catchment earth dams (balleyo), cemented catchments (Berkeds), and bore wells besides some natural rain ponds. Most Berkads and Balleys are privately owned water sources. An exception are five communal Balleys dug by a World Bank project in the 1980s in three sites around Borama, which have not been de-silted since excavation. Most rainwater catchments usually dry up during the dry season and both people and livestock resort to bore wells for water or to communal hand-dug shallow wells along the fringes of the mountainous zone.

Management of bore wells is very poor. The bore wells are practically owned by the operators, who fix the price of water for livestock and human consumption. Different water prices are charged by the operators on the different bore wells in coastal areas. The operators are not accountable to any government institution or body, including the beneficiaries of bore wells. Unlike the strategic bore wells in the coastal zone, mini- water systems exist in the major towns and villages in Mountainous Zone. The main sources of mini water systems are hand dug shallow wells connected to pumps run by diesel pumps or by solar installations. Mini water systems are for human consumption and funded by international organizations with the collaboration of local communities and local governments. They are managed by committee and charge affordable rate to beneficiaries. Some of the proceeds are paid to operators for salaries and the remainder is used for spare parts and for repairs and maintenance services.

Government

Justice Sector

The mandate of the Ministry of Justice is ensuring that the fundamental rights and freedoms of Somalilanders, and, as result, have established an effective legal mechanism that protects the citizens against oppression and abuses. Somaliland government carried out all necessary steps of ensuring that an effective and transparent justice system is in place and the rule of law is duly applied with all the necessary court proceedings and investigation processes of civil and criminal cases. Somaliland judiciary courts comprise:

- 1. District courts

- 2. Regional courts

- 3. Appeal courts

- 4. Supreme court

Local Government Sector

Borama District

Borama is the regional capital of the region and has the largest population in the region. The exact figure of the total inhabitants that live Borama town is uncertain, however, it is estimated that total population of not less than 450,000 to 750,000 live inside Borama. Borama population has greatly increased since the collapse of the former regime of Siad Barre due to refugees from Somalia in 1991 and returnees from refugee camps in Ethiopia and Djibouti. Borama is Grade "A" district and is one of the six districts under the provision of Joint Program for Local Governance (JPLG) program. Five UN agencies (UNDP, UN-HABITAT, UNICEF, NCDF, and ILO) work close with the local government to carry out their responsibilities. Each of the five UN agencies involves in a distinct role different from those of the other four. Some of the areas in the JPLG program include financial management, planning and management of projects, local council's parliamentary procedures and leadership. Despite the important roles that Somaliland constitution has assigned to local governments to plays in socio-economic development of its constituency, Borama Local Government is not without challenges.

Regional Governor Office

The regional governor office is in Borama, the regional capital. It was built during colonial administration and had been the office of the then Borama District Commissioner. The building is very old and made of mud bricks and is one of the few public offices not occupied by squatters. It is a historic place and that could be a reason squatters got ashamed of its occupation or it might have been prevented from occupation by patriotic individuals. Whatever the reason might have been, it is a historic icon for the region.

Demographics

Awdal is primarily inhabited by people from the Somali ethnic group, with the Gadabuursi subclan of the Dir especially well represented and considered the predominant clan of the region.[36]

Federico Battera (2005) states about the Awdal Region:

"Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans."[37]

A UN Report published by Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (1999), states concerning Awdal:

"The Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs."[38]

Roland Marchal (1997) states that numerically, the Gadabuursi are the predominant inhabitants of the Awdal Region:

"The Gadabuursi's numerical predominance in Awdal virtually ensures that Gadabuursi interests drive the politics of the region."[39]

Marleen Renders and Ulf Terlinden (2010) both state that the Gadabuursi almost exclusively inhabit the Awdal Region:

"Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security."[40]

There is also a sizeable minority of the Issa subclan of the Dir who mainly inhabit the Zeila district.[41]

Districts

The Awdal region consists of four districts:[5]

| District | Grade | Capital | Comments | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Borama | A | Borama | Regional capital |

|

| Zeila | B | Zeila |

| |

| Lughaya | C | Lughaya |

| |

| Baki | C | Baki |

|

Major towns

Ab=Abasa, Am=Amud, As=Asha-Addo, Ba=Baki, Bor=Borama, Boo=Boon, Ca=Cabdulqaadir, Di=Dilla, Fa=Farda Lagu-Xidh, Fi=Fiqi Aadan, Go=Goroyo Cawl, Ha=Harirad, Ja=Jarahorato, Ji=Jidhi, La=Lawyacado, Lu=Lughaya, Qu=Quljeed, Ru=Ruqi, We=Weeraar, Ze=Zeila

- Borama

- Baki

- Lughaya

- Zeila

- Dilla

- Jarahorato

- Amud

- Abasa

- Fiqi Aadan

- Quljeed

- Boon

- Harirad

- Lawyacado

- Abdulqaadir

See also

- Administrative divisions of Somaliland

- Regions of Somaliland

- Districts of Somaliland

- Somalia–Somaliland border

References

- ^ "President Muse Bihi names new positions". 23 June 2023.

- ^ International Population Conference (IPC). "IPC Population Estimates: Projection (Apr-Jun 2023)" (PDF). Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Somalia". The World Factbook. Langley, Virginia: Central Intelligence Agency.

- ^ a b "Awdal Region" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ^ E. H. M. Clifford, "The British Somaliland-Ethiopia Boundary", Geographical Journal Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Vol. 87, No. 4 (Apr. 1936), p. 296

- ^ "Population Estimation Survey 2014". Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 August 2017.

- ^ Lewis, I. M. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 15. ISBN 978-3-8258-3084-7. Archived from the original on 2 February 2015. Retrieved 15 January 2015.

- ^ Richard Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, 1856; edited with an introduction and additional chapters by Gordon Waterfield (New York: Praeger, 1966), p. 132. For a more recent description, see A. T. Curle, "The Ruined cities of Somalia", Antiquity, 11 (1937), pp. 315-327

- ^ Bosellini, Alfonso. "The Continental Margins of Somalia: Structural Evolution and Sequence Stratigraphy: Chapter 11: African and Mediterranean Margins." (1992): 185-205.

- ^ Awdal "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Somaliland" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Economic Activities "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P.14

- ^ Regional Development planining, Awdal "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal " P.15 Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Education Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Awdal Education "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Somaliland" Archived 15 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Education Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. p.18

- ^ Health Development Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine .P.22

- ^ lABOR AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS "Ministry of National Planning and Development, AWDAL" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. P.26

- ^ a b Awdal Labour "Awdal Ministry of Labour, Somaliland" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Youth and sports sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awda" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P.29

- ^ Religion and Endowment Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal p.32" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Awdal Religion "Ministry of religion" Archived 10 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Agriculture development sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine p.38.

- ^ Somaliland Economic "Somaliland Economic"[permanent dead link]

- ^ Livestock development Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P.48

- ^ Fishers Development Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awda" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P.47

- ^ Industry and commerce sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P.50

- ^ Mining development sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awda" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.P53

- ^ Panning and development 55 "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Somaliland" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. P.58

- ^ road Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. P.64

- ^ Public Works, Housing and Transport sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.p.64

- ^ Civi Aviation Sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Somaliland" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Information and culture sector "Ministry of National Planning and Development, Awdal" Archived 26 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Samatar, Abdi I. (2001) "Somali Reconstruction and Local Initiative: Amoud University," Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies: Vol. 1, Article 9, p. 132.

- ^ Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans.

- ^ UN (1999) Somaliland: Update to SML26165.E of 14 February 1997 on the situation in Zeila, including who is controlling it, whether there is fighting in the area, and whether refugees are returning. "The Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs." p. 5.

- ^ Marchal, Roland (1997). "United Nations Development Office for Somalia: Studies on Governance: Awdal Region".

The Gadabuursi's numerical predominance in Awdal virtually ensures that Gadabuursi interests drive the politics of the region.

- ^ Renders, Marleen; Terlinden, Ulf. "Chapter 9: Negotiating Statehood in a Hybrid Political Order: The Case of Somaliland". In Tobias Hagmann; Didier Péclard (eds.). Negotiating Statehood: Dynamics of Power and Domination in Africa (PDF). p. 191. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security.

- ^ Janzen, J.; von Vitzthum, S.; Somali Studies International Association (2001). What are Somalia's Development Perspectives?: Science Between Resignation and Hope? : Proceedings of the 6th SSIA Congress, Berlin 6-9 December 1996. Proceedings of the ... SSIA-Congress. Das Arabische Buch. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-86093-230-8. Archived from the original on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 20 July 2018.