Spanish Civil War: Difference between revisions

Via strass (talk | contribs) m →The war: 1936: syntax, rm unnecessary link |

Via strass (talk | contribs) m →The war: 1937: syntax, rm link |

||

| Line 117: | Line 117: | ||

==The war: 1937== |

==The war: 1937== |

||

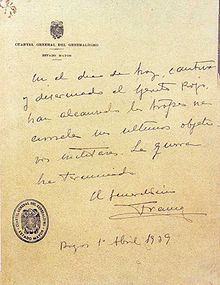

[[Image:Espagne guerre octo.png|right|thumb|Situation of the fronts in |

[[Image:Espagne guerre octo.png|right|thumb|Situation of the fronts in October [[1937]].]] |

||

{{Main|Spanish Civil War chronology 1937}} |

{{Main|Spanish Civil War chronology 1937}} |

||

With his ranks being swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February of 1937, but failed again. |

With his ranks being swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February of 1937, but failed again. |

||

Revision as of 15:16, 9 June 2007

| Spanish Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

A Spanish Republican soldier falls in battle (Photographer – Robert Capa) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

With the support of: |

With the support of: | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Manuel Azaña Francisco Largo Caballero Juan Negrín |

Francisco Franco Gonzalo Queipo de Llano Emilio Mola José Sanjurjo | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~500,000[2] | |||||||

The Spanish Civil War was a major conflict in Spain that started after an attempted coup d'état committed by parts of the army against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. The Civil War devastated Spain from July 17, 1936 to April 1, 1939, ending with the victory of the rebels and the founding of a dictatorship led by the Nationalist General Francisco Franco. The supporters of the Republic, or Republicans (republicanos), gained the support of the Soviet Union and Mexico, while the followers of the Rebellion, also called Nationals (nacionales), received the support of the major European Axis powers of Germany and Italy. The United States remained officially neutral, but sold airplanes to the Republic and gasoline to the Francisco Franco regime.

Prelude to the war

Historical context

Spain had undergone several civil wars and revolts, carried out by both the reformists and the conservatives, who tried to displace each other from power. While the reformists tried to abolish the absolutist monarchy in the country to end the old regime and found a new model of state, the most traditionalist sectors of the political sphere systematically tried to avert these reforms and to sustain the monarchy. The Infante Carlos and his descendants rallied to the cry of "God, Country and King" and fought for the cause of Spanish tradition (absolutism and Catholicism) against the liberalism and later the republicanism of the Spanish governments of the day, and initiatives like the founding of the First Spanish Republic by the republicans in 1873, began to establish tendencies in the Spanish concept of the state, which, along with other causes, would later culminate in the Civil War of 1936.

The Spanish Civil War had large numbers of non-Spanish citizens participating in combat and advisory positions. Foreign governments contributed large amounts of financial assistance and military aid to forces led by Generalísimo Francisco Franco and to those fighting on behalf of the Second Spanish Republic.

Evacuation of Children

As war proceeded in the Northern front, the Republican authorities arranged the evacuation of children. These Spanish War children were shipped to Britain, Belgium, the Soviet Union and other European countries. Those in Western European countries returned to their families after the war, but many of those in the Soviet Union, from Communist families, remained and experienced the Second World War and its effects of the Soviet Union.

Like the Republican side, the Nationalist side of Franco also arranged evacuations of children, women and elderly from war zones. Refugee camps for those civilians evacuated by the Nationalists were set up in Portugal, Italy, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium.

Pacifism in Spain

In the 1930s Spain also became a focus for pacifist organizations including the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the War Resisters League and the War Resisters' International (whose president was the British MP and Labour Party leader George Lansbury). With their focus on government action and military reaction, and against the background of the terrible violence that took place, academic historians, authors, journalists and film-makers have all paid attention to the great political machines that were at work, and have largely overlooked many non-governmental international and grass roots movements, including the 'insumisos' ('defiant ones') who argued and worked for non-violent strategies.

Prominent Spanish pacifists such as Amparo Poch y Gascón and José Brocca supported the Republicans. As American author Scott H. Bennett has demonstrated, 'pacifism' in Spain certainly did not equate with 'passivism', and the dangerous work undertaken and sacrifices made by pacifist leaders and activists such as Poch and Brocca show that 'pacifist courage is no less heroic than the miltary kind' (Bennett, 2003: 67-68). Brocca argued that Spanish pacifists had no alternative but to make a stand against fascism. He put this stand into practice by various means including organising agricultural workers to maintain food supplies and through humanitarian work with war refugees. [3]

Atrocities during the war

Atrocities were committed on both sides during the war. The use of terror against civilians foreshadowed World War II. Atrocities on the Republican side were committed by groups of radical leftists (mainly anarchists and communists) against the rebel supporters, including the nobility, former landowners, rich farmers, industrialists and the Church. Other repressive actions in the Republican side were committed by specific factions such as the Stalinist NKVD (the Soviet secret police)[4]. Note that these crimes committed by the NKVD were carried out not only against the Nationalists but also against all those who did not share their ideology, even if they were fighting on the Republican side. In addition, many Republican leaders, such as Lluís Companys, president of the Generalitat de Catalunya, the autonomous government of Catalonia, that remained loyal to the Republic, carried out numerous actions to mediate in cases of deliberate executions of the clergy[5].

Unlike the Republican side, where the atrocities were not typically carried out by the government but by radical leftists or specific factions such as the Stalinist NKVD, in the case of the Nationalist side these atrocities were ordered by fascist authorities in order to eradicate any trace of leftism in Spain. This included the aerial bombing of cities in the Republican territory, carried out mainly by the Luftwaffe volunteers of the Condor Legion and the Italian air force volunteers of the Corpo Truppe Volontarie (Madrid, Barcelona, Valencia, Guernica, and other cities, counted tens of thousands of deaths due to these bombardments), the execution of school teachers (because the efforts of the Republic to promote laicism and to displace the Church from the education system, and the closing of religious schools, were considered by the Nationalist side as an attack on the Church), the execution of individuals because of accusations of anti-clericalism, the massive killings of civilians in the liberated cities, the execution of unwanted individuals (including non-combatants such as trade-unionists and known Republican sympathisers) and their entire families, etc[6].

Atrocities by the Left during what has been termed Spain's red terror took a great toll on the Catholic faithful, especially clerics, as churches, convents and monasteries were desecrated, pillaged and burned, 13 bishops, 4184 diocesan priests, 2365 male religious (among them 114 Jesuits) and 283 nuns were murdered, and there are accounts of Catholic faithful being forced to swallow rosary beads, thrown down mine shafts and priests being forced to dig their own graves before being buried alive. [7]

The war: 1936

In the early days of the war, over 50,000 people who were caught on the "wrong" side of the lines were assassinated or summarily executed. The numbers were probably comparable on both sides. In these paseos ("promenades"), as the executions were called, the victims were taken from their refuges or jails by armed people to be shot outside of town. The corpses were abandoned or interred in digs made by the victims themselves. Local police just noted the apparition of the corpses. Probably the most famous such victim was the poet and dramatist Federico García Lorca. The outbreak of the war provided an excuse for settling accounts and resolving long-standing feuds. Thus, this practice became widespread during the war in areas conquered. In most areas, even within a single given village, both sides committed assassinations.

Any hope of a quick ending to the war was dashed on July 21, the fifth day of the rebellion, when the Nationalists captured the main Spanish naval base at Ferrol in northwestern Spain. This encouraged the Fascist nations of Europe to help Franco, who had already contacted the governments of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy the day before. On July 26, the future Axis Powers cast their lot with the Nationalists. Nationalist forces under Franco won another great victory on September 27 when they relieved the Alcázar at Toledo.

A Nationalist garrison under Colonel Moscardo had held the Alcázar in the center of the city since the beginning of the rebellion, resisting for months against thousands of Republican troops who completely surrounded the isolated building. The inability to take the Alcázar was a serious blow to the prestige of the Republic, as it was considered inexplicable in view of their numerical superiority in the area. Two days after relieving the siege, Franco proclaimed himself Generalísimo and Caudillo ("chieftain") while forcibly unifying the various Falangist and Royalist elements of the Nationalist cause. In October, the Nationalists launched a major offensive toward Madrid, reaching it in early November and launching a major assault on the city on November 8. The Republican government was forced to shift from Madrid to Valencia, out of the combat zone, on November 6. However, the Nationalists' attack on the capital was repulsed in fierce fighting between November 8 and 23. A contributory factor in the successful Republican defense was the arrival of the International Brigades, though only around 3000 of them participated in the battle. Having failed to take the capital, Franco bombarded it from the air and, in the following two years, mounted several offensives to try to encircle Madrid. (See also Siege of Madrid (1936-39))

On November 18, Germany and Italy officially recognized the Franco regime, and on December 23, Italy sent "volunteers" of its own to fight for the Nationalists.

The war: 1937

With his ranks being swelled by Italian troops and Spanish colonial soldiers from Morocco, Franco made another attempt to capture Madrid in January and February of 1937, but failed again.

On February 21 the League of Nations Non-Intervention Committee ban on foreign national "volunteers" went into effect. The large city of Málaga was taken on February 8. On March 7 German Condor Legion equipped with Heinkel He 51 biplanes arrived in Spain; on April 26 they bombed the town of Guernica in the Basque Country; two days later, Franco's men entered the town.

After the fall of Guernica, the Republican government began to fight back with increasing effectiveness. In July, they made a move to recapture Segovia, forcing Franco to pull troops away from the Madrid front to halt their advance. Mola, Franco's second-in-command, was killed on June 3, and in early July, despite the fall of Bilbao in June, the government actually launched a strong counter-offensive in the Madrid area, which the Nationalists repulsed with some difficulty. The clash was called "Battle of Brunete" (Brunete is a town in the province of Madrid).

After that, Franco regained the initiative, invading Aragon in August and then taking the city of Santander (now in Cantabria). Two months of bitter fighting followed and, despite determined Asturian resistance, Gijón (in Asturias) fell in late October, which effectively ended the war in the North.

Meanwhile, on August 28, the Vatican recognized Franco, and at the end of November, with the Nationalists closing in on Valencia, the government moved again, to Barcelona

The war: 1938

The Battle of Teruel was an important confrontation between Nationalists and Republicans. The city belonged to the Nationalists at the beginning of the battle, but the Republicans conquered it in January. The Nationalists launched an offensive and recovered the city by February 22. On April 14, the Nationalists broke through to the Mediterranean Sea, cutting the government-held portion of Spain in two. The government tried to sue for peace in May, but Franco demanded unconditional surrender, and the war raged on.

There were several reasons for the war, many of them long-term tensions that had escalated over the years. Spain had undergone a number of different systems of rule during the early 19th Century. A monarchy under Alfonso XIII lasted from 1887 to 1924, but was replaced with the military dictatorship of Primo de Rivera. In 1928, this was succeeded by another two years of monarchy until the Second Republic was declared in 1931. This Republic was led by a coalition of the left and center. A number of controversial reforms were passed, such as the Agrarian Law of 1932, distributing land among poor peasants. Millions of Spaniards had been living in more or less absolute poverty under the firm control of the aristocratic landowners in a feudal-like system. These reforms, along with anticlericalist acts and the expulsion of Muslims, as well as military cut-downs and reforms, created strong opposition from the former elite.

The Republicans were also split among themselves. The left and the conservatives had many conflicting ideas. The Cortes (Spanish Parliament) consisted of 16 parties in 1931. When autonomy was granted to Catalonia and the Basque Provinces in 1932, a nationalist coup was attempted but failed. An anarchist uprising resulted in the massacre of hundreds of rebels. In addition to this opposition, Spanish export decreased with 75% between 1931 and 1942. Thus, the rural reforms were of little help to the starving lower class. Economic difficulties on the whole prevented the Republic from doing anything constructive during its time in government.

The government now launched an all-out campaign to reconnect their territory in the Battle of the Ebro, beginning on July 24 and lasting until November 26. The campaign was militarily unsuccessful, and was undermined by the Franco-British appeasement of Hitler in Munich. The concession of Czechoslovakia destroyed the last vestiges of Republican morale by ending all hope of an anti-fascist alliance with the great powers. The retreat from the Ebro all but determined the final outcome of the war. Eight days before the new year, Franco struck back by throwing massive forces into an invasion of Catalonia.

The war: 1939

The Nationalists conquered Catalonia in a whirlwind campaign during the first two months of 1939. Tarragona fell on January 14, followed by Barcelona on January 26 and Girona on February 5. Five days after the fall of Girona, the last resistance in Catalonia was broken.

On February 27, the governments of the United Kingdom and France recognized the Franco regime.

Only Madrid and a few other strongholds remained for the government forces. On March 28, with the help of pro-Franco forces inside the city (the "fifth column" General Mola had mentioned in propaganda broadcasts in 1936), Madrid fell to the Nationalists. The next day, Valencia, which had held out under the guns of the Nationalists for close to two years, also surrendered. Victory was proclaimed on April 1, when the last of the Republican forces surrendered.

After the end of the War, there were harsh reprisals against Franco's former enemies on the left, when thousands of Republicans were imprisoned and between 10,000 and 28,000 executed. Many other Republicans fled abroad, especially to France and Mexico.

Social revolution

In the anarchist-controlled areas, Aragon and Catalonia, in addition to the temporary military success, there was a vast social revolution in which the workers and the peasants collectivised land and industry, and set up councils parallel to the paralyzed Republican government. This revolution was opposed by both the Soviet-supported communists, who ultimately took their orders from Stalin's politburo (which feared a loss of control), and the Social Democratic Republicans (who worried about the loss of civil property rights). The agrarian collectives had considerable success despite opposition and lack of resources, as Franco had already captured lands with some of the richest natural resources.

As the war progressed, the government and the communists were able to leverage their access to Soviet arms to restore government control over the war effort, both through diplomacy and force. Anarchists and the POUM were integrated with the regular army, albeit with resistance; the POUM was outlawed and falsely denounced as an instrument of the fascists. In the May Days of 1937, many hundreds or thousands of anti-fascist soldiers fought one another for control of strategic points in Barcelona, recounted by George Orwell in Homage to Catalonia.

People

Template:Important Figures in the Spanish Civil War

Political parties and organizations

| The Popular Front (Republican) | Supporters of the Popular Front (Republican) | Nationalists (Francoist) |

|---|---|---|

|

The Popular Front was an electoral alliance formed between various left-wing and centrist parties for elections to the Cortes in 1936, in which the alliance won a majority of seats.

|

|

Virtually all Nationalist groups had very strong Roman Catholic convictions and supported the native Spanish clergy.

|

Conclusion

The impact of the war was massive: the Spanish economy took decades to recover. The political and emotional repercussions of the war reverberated far beyond the boundaries of Spain and sparked passion among international intellectual and political communities, passions that still are present in Spanish politics today.

Notes

- ^ While the Spanish Nationalists received free and unconditional support from the two major European Axis Powers (Germany and Italy), the Republic had to purchase Soviet assistance with the official gold reserves of the Bank of Spain (see Moscow Gold), obtaining armament of marginal quality that, in addition, was sold at deliberately inflated prices. The cost of the Soviet support to the Republic raised more than US$500 million, which supposed two-thirds of the gold reserves that Spain had at the begin of the war.

- ^ The number of casualties is disputed; estimates generally suggest that between 500,000 and 1 million people were killed. Over the years, historians kept lowering the death figures and modern research concludes that 500,000 deaths is the correct figure. Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (2001), pp. xviii & 899–901, inclusive.

- ^ Bennett, Scott, Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963, Syracuse NY, Syracuse University Press, 2003; Prasad, Devi, War is A Crime Against Humanity: The Story of War Resisters' International, London, WRI, 2005. Also see Hunter, Allan, White Corpsucles in Europe, Chicago, Willett, Clark & Co., 1939; and Brown, H. Runham, Spain: A Challenge to Pacifism, London, The Finsbury Press, 1937.

- ^ Article that explains how the Stalinist NKVD tortured the prisoners in the Checas: 1

- ^ History website where this situation is explained: 1.

- ^ Examples of this kind of tactics on the Nationalist side are the Bombing of Guernica and the Massacre of Badajoz [1], [2]. Other stories of people who were murdered by the fascists because of their beliefs: [3][4] (Sources in Spanish).

- ^ Beevor, Antony The Battle for Spain (Penguin 2006).

- ^ Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War, (1961) p. 176

Bibliography

- Alpert, Michael (2004). A New International History of the Spanish Civil War. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-1171-1.

- Beevor, Antony (2001 reissued). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-100148-8.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Beevor, Antony (2006). The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297-848325.

- Bennett, Scott (2003). Radical Pacifism: The War Resisters League and Gandhian Nonviolence in America, 1915-1963. Syracuse NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-3028-X.

- Brenan, Gerald (1990, reissued). The Spanish labyrinth: an account of the social and political background of the Civil War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39827-4.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Carr, Raymond (Introduction; no editor named), Images of the Spanish Civil War, London (Allen & Unwin) 1986.

- Doyle, Bob (2006). Brigadista – an Irishman's fight against fascism. Dublin: Currach Press. ISBN 1-85607-939-2.

- Enzensberger,Christian,"The short summer of Anarchy"

- Francis, Hywel (2006). Miners against Fascism: Wales and the Spanish Civil War. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Graham, Helen (2002). The Spanish republic at war, 1936–1939. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-45932-X.

- Greening, Edwin (2006). From Aberdare to Albacete: A Welsh International Brigader's Memoir of His Life. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Howson, Gerald (1998). Arms for Spain. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0-312-24177-1.

- Ibarruri, Dolores (1976). They Shall Not Pass: the Autobiography of La Pasionaria (translated from El Unico Camino by Dolores Ibarruri). New York: International Publishers. ISBN 0-7178-0468-2.

- Jackson, Gabriel (1965). The Spanish Republic and the Civil War, 1931–1939. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00757-8.

- Jellinek, Frank (1938). The Civil War in Spain. London: Victor Gollanz (Left Book Club).

- Koestler, Arthur (1983). Dialogue with death. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-34776-5.

- Kowalsky, Daniel. La Union Sovietica y la Guerra Civil Espanola. Barcelona: Critica. ISBN 84-8432-490-7.

- Malraux, André (1941). L'Espoir (Man's Hope). New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0-394-60478-4.

- Moa, Pío; Los Mitos de la Guerra Civil, La Esfera de los Libros, 2003.

- O'Riordan, Michael (2005). The Connolly Column. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Orwell, George (2000, first published in 1938). Homage to Catalonia. London: Penguin Books in association with Martin Secker & Warburg. ISBN 0-14-118305-5.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Payne, Stanley (2004). The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet Union, and Communism. New Haven; London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10068-X.

- Prasad, Devi (2005). War is a Crime Against Humanity: The Story of War Resisters' International. London: War Resisters' International, wri-irg.org. ISBN 0-903517-20-5.

- Preston, Paul (1978). The Coming of the Spanish Civil War. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-23724-2.

- Preston, Paul (1996). A Concise history of the Spanish Civil War. London: Fontana. ISBN 978-0006863731.

- Puzzo, Dante Anthony (1962). Spain and the Great Powers, 1936–1941. Freeport, N.Y: Books for Libraries Press (originally Columbia University Press, N.Y.). ISBN 0-8369-6868-9.

- Radosh, Ronald (2001). Spain betrayed: the Soviet Union in the Spanish Civil War. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-08981-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Rust, William (2003 Reprint of 1939 edition). Britons in Spain: A History of the British Battalion of the XV International Brigade. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren and Pell.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - Stradling, Rob (1996). Cardiff and The Spanish Civil War. Cardiff (CF1 6AG): Butetown History and Arts Centre. ISBN 1-898317-06-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Taafle, Peter reviews Battle for Spain – The Spanish Civil War of 1936–39 by Anthony Beevor (Weidenfeld and Nicolson £25).

- Thomas, Hugh (2003 reissued). The Spanish Civil War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-101161-0.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Walters, Guy (2006). Berlin Games – How Hitler Stole the Olympic Dream (Chapter Six contains an account of how the outbreak of fighting in Barcelona affected those visiting the abortive People's Olympiad). London, New York: John Murray (UK), HarperCollins (US). ISBN 0-7195-6783-1, 0-0608-7412-0.

- Wheeler, George (2003). To Make the People Smile Again: a Memoir of the Spanish Civil War (foreword by Jack Jones, edited by David Leach). Newcastle upon Tyne: Zymurgy Publishing. ISBN 1-903506-07-7.

- Williams, Alun Menai (2004). From the Rhondda to the Ebro: The Story of a Young Life. Pontypool, Wales (NP4 7AG): Warren & Pell.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link)

See also

- Second Spanish Republic

- Anarchism in Spain

- Spanish Revolution

- International Brigades

- Ireland and the Spanish Civil War

- Bombing of Guernica

- Proxy war

- European Civil War

- Spanish Maquis

Related films

- España 1936, pro-Republican documentary by Luis Buñuel.

- The Spanish Earth (Joris Ivens, 1937; pro-Republican documentary, narrated by Ernest Hemingway and John Dos Passos.

- Defenders of the Faith, 1938; pro-Nationalist documentary by Russell Palmer

- Raza (Jose Luis Saenz de Heredia, 1942)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls (Sam Wood, 1943, from the Ernest Hemingway novel)

- The Fallen Sparrow, (Richard Wallace, 1943, from the Dorothy B. Hughes novel; John Garfield played a Spanish Civil War veteran who has returned to New York City to find out the truth about his friend's death).

- The Heifer (La vaquilla) (Luis García Berlanga, 1985)

- The Spanish Civil War (BBC-Granada, 1987)

- ¡Ay, Carmela! (Carlos Saura, Spain/Italy 1990) Comedy/drama about two actors who find themselves on the wrong side of the front line.

- Land and Freedom (Ken Loach, 1995) The war seen through the eyes of a British volunteer.

- Libertarias (Vicente Aranda, 1996)

- Vivir la Utopia (Living Utopia) by Juan Gamero, Arte-TVE, Catalunya 1997

- La Lengua de las Mariposas (Butterflies), José Luis Cuerda, 1999)

- The Devil's Backbone (El espinazo del diablo) (Guillermo del Toro, 2001)

- Soldados de Salamina (David Trueba, 2002)

- Pan's Labyrinth (El Laberinto del Fauno) (Guillermo del Toro, 2006)

Related literature

- Homage to Catalonia by George Orwell(1938)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway (1940)

- 40 Preguntas Fundamentales sobre la Guerra Civil by Stanley G. Payne (2006)

- The Living and the Dead by Patrick White (1941)

- As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning by Laurie Lee (1969)

- A Moment of War by Laurie Lee (1991)

- The Blind Assassin by Margaret Atwood (2000)

- The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafón (2001)

- L'espoir by Andre Malraux

- Diamond square by Mercè Rodoreda (1962)

- Les Grands cimetieres sous la Lune by Georges Bernanos

- Spain in my hearth (España en el corazón) by Pablo Neruda

- Labyrinth of Struggle by Mauricio Escobar (2006)

On the immediate Post-Civil War:

External links

- Imperial War Museum Collection of Spanish Civil War Posters hosted by AHDS Visual Arts

- Documents on Irish involvement in the SCW 1936–39

- The Spanish Civil War, by George Orwell

- Constitución de la República Española (1931)

- Professor Marek Jan Chodakiewicz on The Spanish Civil War

- A collection of essays by Albert and Vera Weisbord with about a dozen essays written during and about the Spanish Civil War.

- Anarchism in the Spanish Revolution

- The Anarcho-Statists of Spain, a different view of the anarchists in the Spanish Civil War

- A reply to the above by an anarchist

- A description, according to the Vatican, of the religious persecution suffered by Catholics during the Spanish Civil War (in Spanish).

- A History of the Spanish Civil War, excerpted from a U.S. government country study.

- Spanish Civil War Info From Spartacus Educational

- La Cucaracha, The Spanish Civil War Diary, an excellent and detailed chronicle of the events of the war

- American Jews in Spanish Civil War

- Ronald Hilton, Spain, 1931–36, From Monarchy to Civil War, An Eyewitness Account,

- Columbia Historical Review Dutch Involvement in the Spanish Civil War

- Noam Chomsky's Objectivity and Liberal Scholarship

- Civil War Documentaries made by the CNT

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution text archive in the libcom.org library

- Spanish Civil War and Revolution image gallery – photographs and posters from the conflict

- The Spanish Civil War and Revolution 1936–1939 Web sites, articles, books & pamphlets online, and films (on Tidsskriftcentret.dk)

- Causa General, conclusions of the process started by Franco's government after the war to judge their enemies' actions during the conflict

- With the Reds in Andalusia, By Joe Monks, 1985. An Irish member of the Int Brigade.

- Irish and Jewish Volunteers in the Spanish Anti-Fascist War Pamphlet by Manus O'Riordan

- O'Duffy's Bandera in Spain

- The Spanish Revolution, 1936–39 articles & links, from Anarchy Now!

- Juan García Oliver, Los Organismos Revolucionarios: El Comité Central de las Milicias Antifascistas de Cataluña

- Asociacion Frente de Aragonphotos of the uniforms and insignia of Spanish Civil War units.

- Aircraft of the Spanish Civil War