American imperialism: Difference between revisions

→Second school of thought: "US empire never existed": not just "U.S. citizens" who defend this role |

|||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

==Second school of thought: "US empire never existed" == |

==Second school of thought: "US empire never existed" == |

||

Many |

Many, however, defend the historical role of the US against allegations of imperialism. This is especially common among prominent mainstream political figures; former [[Secretary of Defense]] [[Donald Rumsfeld]], for example, has said: |

||

:"we don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been."<ref>{{cite news | author=Bookman, Jay | title=Let's just say it's not an empire | url=http://www.dailykos.net/archives/003167.html | publisher=Atlanta Journal-Constitution | date = [[June 25]], [[2003]]}}</ref> |

:"we don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been."<ref>{{cite news | author=Bookman, Jay | title=Let's just say it's not an empire | url=http://www.dailykos.net/archives/003167.html | publisher=Atlanta Journal-Constitution | date = [[June 25]], [[2003]]}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:01, 13 November 2007

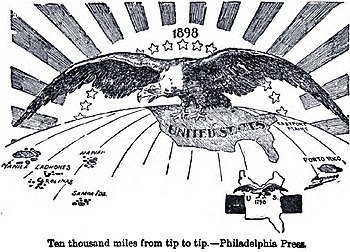

American Empire is a term relating to the political, economic, and cultural influence of the United States. The concept of an American Empire has its origins in the Spanish-American War of 1898. The source of this concept arises from classical Marxist-Leninist theories of anti-imperialism to classical and modern liberal theorists opposed to U.S. policy.

Definition of empire

The term imperialism was coined in the mid-1800s.[1] It was first widely applied to the US by the American Anti-Imperialist League, founded in 1898 to oppose the Spanish-American War and the subsequent post-war military occupation and what the league took to be brutalities committed by US forces in the Philippines. A leader and founding member of the League was Mark Twain, who defended its views in the following manner:

I have read carefully the treaty of Paris, and I have seen that we do not intend to free, but to subjugate the people of the Philippines. We have gone there to conquer, not to redeem. It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way. And so I am an anti-imperialist. I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.

— Mark Twain, New York Herald, Oct. 15, 1900.

The Oxford English Dictionary gives three definitions of imperialism:

- An Imperial system of government; the rule of an emperor, esp. when despotic or arbitrary.

- The principle or spirit of empire; advocacy of what are held to be imperial interests.

- Used disparagingly. In Communist writings: the imperial system or policy of the Western powers. Used conversely in some Western writings: the Imperial system or policy of the Communist powers.[2]

Debate exists over whether the U.S. is an empire in the politically-charged sense of the latter two definitions. However, Historian Archibald Paton Thorton and Stuart Creighton Miller argue against the very coherence of the concept. Miller argues that the overuse and abuse of the term "imperialism" makes it nearly meaningless as an analytical concept.[3] Thorton wrote that "imperialism is more often the name of the emotion that reacts to a series of events than a definition of the events themselves. Where colonization finds analysts and analogies, imperialism must contend with crusaders for and against."[4] Political theorist Michael Walzer argues that the term "hegemony" is better than "empire" to describe the US' role in the world.[5]

American exceptionalism

Stuart Creighton Miller points out that the question of U.S. imperialism has been the subject of agonizing debate ever since the United States acquired formal empire at the end of the nineteenth century during the 1898 Spanish-American War. Miller argues that this agony is because of America’s sense of innocence, produced by a kind of "immaculate conception" view of America's origins. When European settlers came to America they miraculously shed their old ways upon arrival in the New World, as one might discard old clothing, and fashioned new cultural garments based solely on experiences in a new and vastly different environment. Miller believes that school texts, patriotic media, and patriotic speeches on which Americans have been reared do not stress the origins of America's system of government, that these sources often omit or downplay that the "United States Constitution owes its structure as much to the ideas of John Locke and Thomas Hobbes as to the experiences of the Founding Fathers; that Jeffersonian thought to a great extent paraphrases the ideas of earlier Scottish philosophers; and that even the unique frontier egalitarian has deep roots in seventeenth century English radical traditions."[6]

Philosopher Douglas Kellner traces the identification of American exceptionalism as a distinct phenomenon back to 19th century French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, who concluded by agreeing that the U.S., uniquely, was "proceeding along a path to which no limit can be perceived."[7]

American exceptionalism is popular among people within the US,[8] but its validity and its consequences are disputed. Miller argues that U.S. citizens fall within three schools of thought about the question whether the United States is imperialistic:

- Overly self-critical Americans tend to exaggerate the nation’s flaws, failing to place them in historical or worldwide contexts.

- In the middle are Americans who assert that "Imperialism was an aberration."[9]

- At the other end of the scale, the tendency of highly patriotic Americans is to deny such abuses and even assert that they could never exist in their country. As a Monthly Review editorial describes the phenomenon,

- "in Britain, empire was justified as a benevolent 'white man’s burden'. And in the United States, empire does not even exist; 'we' are merely protecting the causes of freedom, democracy, and justice worldwide."[10]

First school of thought: "Empire at the heart of US foreign policy"

Since the Spanish-American War, Marxists and the New Left tend to view imperialism as an unmitigated obsession. US imperialism, in their view, traces its beginning not to the Spanish-American war, but to Jefferson’s purchase of the Louisiana Territory, or even to the displacement of Native Americans prior to the American Revolution, and continues to this day. Historian Sidney Lens argues that

- "the United States, from the time it gained its own independence, has used every available means—political, economic, and military—to dominate other nations."[11]

Numerous U.S. foreign interventions, ranging from early actions under the Monroe Doctrine to 21st-century interventions in the Middle East, are typically described by these authors as imperialistic. Some critics of imperialism have a more positive view of America's early era, however. Prominent conservative writer Patrick Buchanan argues that the modern United States' drive to empire is "far from what the Founding Fathers had intended the young Republic to become."[12] This latter point of view is often identified with American isolationism, in the tradition of either the Old Right (Buchanan), or libertarianism (for example, Justin Raimondo).

Lens describes American exceptionalism as a myth, which allows any number of "excesses and cruelties, though sometimes admitted, usually [to be] regarded as momentary aberrations."[13] Linguist and political critic Noam Chomsky argues that it is the result of a systematic strategy of propaganda, maintained by an "elite domination of the media" which allows it to "fix the premises of discourse and interpretation, and the definition of what is newsworthy in the first place, and they explain the basis and operations of what amount to propaganda campaigns."[14]

This critical historical view is usually continued to present US foreign policy. Historian Andrew Bacevich, drawing on the work of Charles Beard and William Appleman Williams, argues that the end of the Cold War did not mark the end of an era in US history, because US foreign policy did not fundamentally change after the Cold War. US foreign policy has long been driven by the desire to expand access to foreign markets in order to benefit the domestic economy. The moralistic reasons given for American foreign intervention mask the true economic reasons, and Bacevich warns that US economic imperialism (in the guise of globalization) may not be in the best interests of the United States.[15]

This is a common extension of the critique of American empire; Buchanan and, from the opposite side of the political spectrum, prominent writer Tariq Ali, argue independently but similarly that acts of terrorism against the United States, such as the September 11, 2001 attacks, are the direct result of the U.S.'s ill-fated attempts to help others out of the nation's endless reserve of kindness and goodwill. Ali claims that "the reasons [for terrorism] are really political. They see the double standards applied by the West: a ten-year bombing campaign against Iraq, sanctions against Iraq which have led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of children, while doing nothing to restrain Ariel Sharon and the war criminals running Israel from running riot against the Palestinians. Unless the questions of Iraq and Palestine are sorted out, these kids will be attracted to violence regardless of whether Osama bin Laden is gotten dead or alive."[16]

Ethnic studies professor Ward Churchill is almost alone, however, in extending this critique further to argue that at least some of the victims of the 9/11 attacks - the "little Eichmanns" who "formed a technocratic corps at the very heart of the US' global financial empire – the 'mighty engine of profit' to which the military dimension of U.S. policy has always been enslaved" - deserved their fates.[17] A different extension is more common; many critics of US imperialism argue, like Marxist sociologist John Bellamy Foster, that the United States' sole-superpower status makes it now the most dangerous world imperialist.[18]

U.S. military bases abroad as a form of empire

Proponents of the idea that the U.S. is an empire point to United States Military Bases abroad as evidence. As of 2005, the United States had military bases in over 36 countries worldwide.[19] Some see another sign of an empire in the Unified Combatant Command, a military group composed of forces from two or more services that has the entire world divided into five areas of military responsibility. Chalmers Johnson argues that America's version of the colony is the military base.[20] Chip Pitts argues similarly that enduring U.S. bases in Iraq suggest a vision of "Iraq as a colony".[21]

After WWII, the US allowed many of its overseas territories or occupations to gain independence. The Philippines (1946), the Panama Canal Zone (1979), the Federated States of Micronesia (1986), Marshall Islands (1986), and Palau (1994) are examples. Some, such as Guam, and Puerto Rico, remain under U.S. control without all the rights and benefits of statehood. Of those former possessions granted independence, most continue to have U.S. bases inside their territories, sometimes despite local popular opinion, as in the case of Okinawa.[22] Additionally, the U.S. has often provided direct military and financial support of autocratic rulers in its former possessions who accomplish US military and mercantile objectives, including Ferdinand Marcos, Park Chung Hee, Omar Torrijos, and Manuel Noriega - though all former US colonies, except Cuba, currently have democratically elected governments. Despite the amount of American military bases overseas, all governments of countries with American military presence retain and, in some cases, have exercised the right to expel all US military personnel from within their borders.

Theories of U.S. empire

Journalist Ashley Smith divides theories of the U.S. as an empire into 5 broad categories: "liberal" theories, "social-democratic" theories, "Leninist" theories, theories of "super-imperialism", and "Hardt-and-Negri-ite" theories.[23] According to Smith,

- A "liberal" theory asserts that U.S. policies are the products of particular elected politicians (e.g. the Bush administration) or political movements (e.g. neo-conservatism). It holds that imperial policies are not the essential result of U.S. political or economic structures, and are clearly hostile and inimical to true US interests and values. This is the original position of Mark Twain and the Anti-Imperialist League and are held today by a good number of US Democratic Party critics of US imperialism, whose proposed solution is typically electing better officials.

- A "social-democratic" theory asserts that imperialistic U.S. policies are the products of the excessive influence of certain sectors of U.S. business and government, the arms industry in alliance with military and political bureaucracies and sometimes other industries such as oil and finance, a combination often referred to as the "military-industrial complex". The complex is said to benefit from war profiteering and the looting of natural resources, often at the expense of the public interest. Old Right journalist John T. Flynn described the position this way.

The enemy aggressor is always pursuing a course of larceny, murder, rapine and barbarism. We are always moving forward with high mission, a destiny imposed by the Deity to regenerate our victims while incidentally capturing their markets, to civilise savage and senile and paranoid peoples while blundering accidentally into their oil wells.

The proposed solution is typically unceasing popular vigilance in order to apply counter-pressure. Chalmers Johnson holds a version of this view; other versions are typically held by anti-interventionists, such as Buchanan, Bacevich, Raimondo, and Flynn.

- A "Leninist" theory asserts that imperialistic U.S. policies are the products of the unified interest of the predominant sectors of U.S. business, which need to ensure and manipulate export markets for both goods and capital. Business, on this Marxist view, essentially controls government, and international military competition is simply an extension of international economic competition, both driven by the inherently expansionist nature of capitalism. The retired Marine Major General Smedley Butler took this view when he said that his job had been to be a "muscle man for big business." The proposed solution is typically revolutionary economic change. The theory was first systematized during the World War I by Russian Bolsheviks Vladimir Lenin and Nikolai Bukharin, although their work was based on that of earlier Marxists, socialists, and anarchists. Ali, Chomsky, Foster, Lens, Howard Zinn, and the Indian journalist Arundhati Roy each hold some version of this view, as does Smith himself.

- A theory of "super-imperialism" is similar to the Leninist theory in its view of the roots of imperialism, but asserts that global economic interdependence has superseded the association of businesses with a single country, so that among developed nations economic and military cooperation is now more common than competition. The central conflict in modern imperialism is said to be between the global core and the global periphery rather than between imperialist powers. Political scientists Leo Panitch and Samuel Gindin hold versions of this view.

- A "Hardt-and-Negri-ite" theory asserts that the Leninist theory was valid when formulated, but that the U.S. is no longer imperialistic in the classic sense, because the world has passed the era of imperialism and entered a new era.[24]) This new era still has colonizing power but has moved from national military forces based on an economy of physical goods to networked biopower based on an informational and affective economy. On this view, the U.S. is central to the development and constitution of a new global regime of international power and sovereignty, termed "Empire", but the "Empire" is decentralized and global, and not ruled by one sovereign state; literary theorist Michael Hardt and philosopher Antonio Negri argue that "the United States does indeed occupy a privileged position in Empire, but this privilege derives not from its similarities to the old European imperialist powers, but from its differences."[25] Hardt and Negri draw on the theories of Spinoza, Foucault, Deleuze, and Italian autonomist marxists. Critical international relations theorist James Der Derian and philosopher Jean Baudrillard hold related though less systematic views, as do many in the traditions of postcolonialism, postmodernism and globalization theory.

Second school of thought: "US empire never existed"

Many, however, defend the historical role of the US against allegations of imperialism. This is especially common among prominent mainstream political figures; former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, for example, has said:

- "we don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic. We never have been."[26]

Military historian Max Boot defends US actions in the Philippines, pointing out that the "atrocities" committed there were relatively insignificant in scope and circumstance, and defending the US motives, which he views as well-intentioned and ultimately beneficial for both America and the Philippines in the long run.

Boot argues that that the United States altruistically went to war with Spain to liberate Cubans, Puerto Ricans, and Filipinos from their tyrannical yoke. If US troops lingered on too long in the Philippines, it was to protect the Filipinos from European predators waiting in the wings for American withdrawal and to tutor them in American-style democracy. In the Philippines, the US followed its usual pattern:

- "the United States would set up a constabulary, a quasi-military police force led by Americans and made up of local enlisted men. Then the Americans would work with local officials to administer a variety of public services, from vaccinations and schools to tax collection. American officials, though often resented, usually proved more efficient and less venal than their native predecessors... Holding fair elections became a top priority because once a democratically elected government was installed, the Americans felt they could withdraw."

Boot argues that this was far from "the old-fashioned imperialism bent on looting nations of their natural resources." Just as with Iraq and Afghanistan, "some of the poorest countries on the planet", in the early 20th century:

- "The United States was least likely to intervene in those nations (such as Argentina and Costa Rica) where American investors held the biggest stakes. The longest occupations were undertaken in precisely those countries--Nicaragua, Haiti, the Dominican Republic--where the United States had the smallest economic stakes... Unlike the Dutch in the East Indies, the British in Malaya, or the French in Indochina, the Americans left virtually no legacy of economic exploitation."[27]

Stuart Creighton Miller states that this more patriotic interpretation is no longer heard very often by historians.[28]

"The Benevolent Empire"

But Boot in fact is willing to use the term "imperialism" to describe United States policy, not only in the early 20th century but "since at least 1803", though this is primarily a simple difference in terminology, since he still argues that US foreign policy has been consistently benevolent.[29] Boot is not alone; as columnist Charles Krauthammer puts it, "People are now coming out of the closet on the word 'empire.'" This embrace of empire is made by many neoconservatives, including British historian Paul Johnson, and writers Dinesh D'Souza and Mark Steyn. It is also made by some liberal hawks, such as political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski, and Michael Ignatieff.[30]

For example, British historian Niall Ferguson, a professor at Harvard University, argues that the United States is an empire, but believes that this is a good thing. Ferguson has drawn parallels between the British Empire and the imperial role of the United States in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, though he describes the United States' political and social structures as more like those of the Roman Empire than of the British. Ferguson argues that all these empires have had both positive and negative aspects, but that the positive aspects of the US empire will, if it learns from history and its mistakes, greatly outweigh its negative aspects.[31]

Third school of thought: "Empire was an aberration"

Another point of view admits United States expansion overseas as imperialistic, but sees this imperialism as a temporary phenomenon, a corruption of American ideals or the relic of a past historical era. Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis argues that Spanish-American War expansionism was a short lived imperialistic impulse and "a great aberration in American history", a very different form of territorial growth than that of earlier American history.[32] Historian Walter LaFeber sees the Spanish-American War expansionism not as an aberration, but as a culmination of United States expansion westward.[33] But both agree that the end of the occupation of the Philippines marked the end of US empire - they deny that present United States foreign policy is imperialist.

Historian Victor Davis Hanson argues that the US does not pursue world domination, but maintains worldwide influence by a system of mutually beneficial exchanges:

- "If we really are imperial, we rule over a very funny sort of empire... The United States hasn't annexed anyone's soil since the Spanish-American War... Imperial powers order and subjects obey. But in our case, we offer the Turks strategic guarantees, political support — and money... Isolationism, parochialism, and self-absorption are far stronger in the American character than desire for overseas adventurism."[34]

Liberal internationalists argue that even though the present world order is dominated by the United States, the form taken by that dominance is not imperial. International relations scholar John Ikenberry argues that international institutions have taken the place of empire;

- "the United States has pursued imperial policies, especially toward weak countries in the periphery. But U.S. relations with Europe, Japan, China, and Russia cannot be described as imperial... the use or threat of force is unthinkable. Their economies are deeply interwoven... they form a political order built on bargains, diffuse reciprocity, and an array of intergovernmental institutions and ad hoc working relationships. This is not empire; it is a U.S.-led democratic political order that has no name or historical antecedent."[35]

I.R. scholar Joseph Nye argues that US power is more and more based on "soft power", which comes from cultural hegemony rather than raw military or economic force. This includes such factors as the widespread desire to emigrate to the United States, the prestige and corresponding high proportion of foreign students at US universities, and the spread of US styles of popular music and cinema. Thus the US, no matter how hegemonic, is no longer an empire in the classic sense.

This point of view might be considered the mainstream or official interpretation of United States history within the US. The United States Information Agency writes that,

- "With the exception of the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, American territory had remained fixed since 1848. In the 1890s a new spirit of expansion took hold... Yet Americans, who had themselves thrown off the shackles of empire, were not comfortable with administering one. In 1902 American troops left Cuba... The Philippines obtained... complete independence in 1946. Puerto Rico became a self-governing commonwealth... and Hawaii became a state in 1959."[36]

A variety of factors may have coincided during the "Age of Imperialism", the later part of the nineteenth century, when the US and the other major powers rapidly expanded their territorial possessions:

- The industry and agriculture of the United States had grown beyond its need for consumption. Powerful business and political figures such as James G. Blaine believed that foreign markets were essential to further economic growth, promoting a more aggressive foreign policy.

- Many of the United States' peer competitors (e.g. the United Kingdom, France, Italy, Belgium, Japan, Germany) were engaged in imperialistic adventures, and the US felt that in order to be a "great power" among "great powers", it had to behave in a similar manner as its peers.

- The prevalence of racism, notably Ernst Haeckel's "biogenic law," John Fiske's conception of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority, and Josiah Strong's call to "civilize and Christianize" - all manifestations of a growing Social Darwinism and racism in some schools of American political thought.[37]

- The development of Frederick Jackson Turner's "Frontier Thesis," which stated that the American frontier was the wellspring of its creativity and virility as a civilization. As the Western United States was gradually becoming less of a frontier and more of a part of America, many believed that overseas expansion was vital to maintaining the American spirit.

- The publication of Alfred T. Mahan's The Influence of Sea Power upon History in 1890, which advocated three factors crucial to The United States' ascension to the position of "world power": the construction of a canal in South America (later influencing the decision for the construction of the Panama Canal), expansion of the U.S. naval power, and the establishment of a trade/military post in the Pacific, so as to stimulate trade with China. This publication had a strong influence on the idea that a strong navy stimulated trade, and influenced policy makers such as Theodore Roosevelt and other proponents of a large navy.

Cultural imperialism

The controversy regarding the issue of alleged US cultural imperialism is largely separate from the debate about alleged US military imperialism; however, some critics of imperialism argue that cultural imperialism is not independent from military imperialism. Edward Said, one of the original scholars to study post-colonial theory, argues that,

So influential has been the discourse insisting on American specialness, altruism and opportunity, that imperialism in the United States as a word or ideology has turned up only rarely and recently in accounts of the United States culture, politics and history. But the connection between imperial politics and culture in North America, and in particular in the United States, is astonishingly direct.[38]

He identifies the way non-US citizens, particularly non-Westerners, are usually thought of within the US in a tacitly racist manner, in a way that allows imperialism to be justified through such ideas as the White Man's Burden.[39]

Scholars who disagree with the theory of US cultural imperialism or the theory of cultural imperialism in general argue that what is regarded as cultural imperialism by many is not connected to any kind of military domination, which has been the traditional means of empire. International relations scholar David Rothkop argues that cultural imperialism is the innocent result of globalization, which allows access to numerous US and Western ideas and products that many non-US and non-Western consumers across the world voluntarily choose to consume. A worldwide fascination with the United States has not been forced on anyone in ways similar to what is traditionally described as an empire, differentiating it from the actions of the British Empire--see the Opium Wars--and other more easily identified empires throughout history. Rothkop identifies the desire to preserve the "purity" of one's culture as xenophobic.[40] Matthew Fraser has a similar analysis, but argues further that the global cultural influence of the US is a good thing.[41]

Notes and references

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (1989). "imperialism". Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (1989). "empire". Retrieved 2006-04-12.

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). "Benevolent Assimilation" The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02697-8. p. 3.

- ^ Thornton, Archibald Paton (September, 1978). Imperialism in the Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-24848-1.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Walzer, Michael. "Is There an American Empire?". www.freeindiamedia.com. Retrieved 2006-06-10.

- ^ Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 1.

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (2003-04-25). "American Exceptionalism". Retrieved 2006-02-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Edwords, Frederick (1987). "The religious character of American patriotism. It's time to recognize our traditions and answer some hard questions". The Humanist (p. 20-24, 36).

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 1-3.

- ^ Magdoff, Harry (2001). "After the Attack...The War on Terrorism". Monthly Review. 53 (6): p. 7.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Lens, Sidney (2003). The Forging of the American Empire. Haymarket Books and Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2100-3. Book jacket.

- ^ Buchanan, Patrick (1999). A Republic, Not and Empire. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-272-X. p. 165.

- ^ Lens (2003), op. cit. Book jacket.

- ^ Chomsky, Noam (1988). Manufacturing Consent. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-375-71449-9.

- ^ Bacevich, Andrew (2004). American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01375-1.

- ^ Ali, Tariq (October 2001). "Tariq Ali on 9/11". Left Business Observer (98).

- ^ Churchill, Ward (2003). Reflections on the Justice of Roosting Chickens. AK Press. ISBN 1-902593-79-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Foster, John Bellamy (2003). "The New Age of Imperialism". Monthly Review.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Base Structure Report" (PDF). USA Department of Defense. 2003. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ^ America's Empire of Bases

- ^ Pitts, Chip (November 8, 2006). "The Election on Empire". The National Interest.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Patrick Smith, International Herald Tribune, March 6, 1998, http://www.iht.com/articles/1998/03/06/edsmith.t_0.php

- ^ Smith, Ashley (June 24, 2006). "The Classical Marxist Theory of Imperialism". Socialism 2006. Columbia University.

{{cite conference}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Hardt and Negri no longer hold that the world has already entered the new era of Empire, but only that it is emerging. According to Hardt, the Iraq War is a classically imperialist war, but represents the last gasp of a doomed strategy. Hardt, Michael (July 13, 2006). "From Imperialism to Empire". The Nation.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Negri, Antonio (2000). Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00671-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) p. xiii-xiv. - ^ Bookman, Jay (June 25, 2003). "Let's just say it's not an empire". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Boot, Max (November 2003). "Neither New nor Nefarious: The Liberal Empire Strikes Back". Current History. 102 (667).

- ^ Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 136.

- ^ Boot, Max (May 6, 2003). "American Imperialism? No Need to Run Away From the Label". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Heer, Jeet (March 23, 2003). "Operation Anglosphere". Boston Globe.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ferguson, Niall (June 2, 2005). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-101700-7.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Miller (1982), op. cit. p. 3.

- ^ Lafeber, Walter. The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860-1898. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9048-0.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (2002). "A Funny Sort of Empire". National Review.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ikenberry, G. John (March/April 2004). "Illusions of Empire: Defining the New American Order". Foreign Affairs.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ ed. George Clack (September 1997). "A brief history of the United States". A Portrait of the USA. United States Information Agency. Retrieved 2006-03-20.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Thomas Friedman, "The Lexus and the Olive Tree", p. 381, and Manfred Steger, "Globalism: The New Market Ideology," and Jeff Faux, "Flat Note from the Pied Piper of Globalization," Dissent, Fall 2005, pp. 64-67.

- ^ Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism, speech at York University, Toronto, February 10, 1993.

- ^ Idem.

- ^ Rothkop, David (June 22, 1997). "Globalization and Culture". Foreign Policy.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Fraser, Matthew (2005). Weapons of Mass Distraction: Soft Power and American Empire. St. Martin's Press.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)

See also

External links

- Bellah, Robert N. (2003). "Imperialism, American-style". The Christian Century: 20–25.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - "America and Empire: Manifest Destiny Warmed Up?". The Economist.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help) Argues that the U.S. is going through an imperial phase, but like previous phases, this will be temporary, since (they argue) empire is incompatible with traditional U.S. policies and beliefs. - "9/11 and the American Empire". Retrieved 2006-05-05. A website that looks at the events of 9/11 which point towards government orchestration with the intention of using mass public fear as a catalyst for creating a stronger American Empire..

- "The American Empire Project". Retrieved 2007-07-10. A series of books from left-wing writers such as Noam Chomsky, critical of the "American Empire".

- "An American Question". tygerland.net by AS Heath. Retrieved 2006-06-10.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) July 25, 2005 - Boot, Max (2003). "American imperialism? No need to run away from label". USA today.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Argues that "U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century." - Hitchens, Christopher, "Imperialism: Superpower dominance, malignant and benign". Slate.com. Retrieved 2006-06-10., warns that the U.S.—whether or not you call it an empire—should be careful to use its power wisely.

- Johnson, Paul, "America's New Empire for Liberty". Article from conservative writer and historian, argues that the U.S. has always been an empire—and a good one at that.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (2006). "Empire Falls Alexander J. Motyl". Foreign Affairs.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Two new books attempt to explain U.S. power and policy in imperial terms. - "Empire?". Global Policy Forum. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

- Niall Ferguson. ""Empire Falls"". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- "The American Empire:Pax Americana or Pox Americana?". Monthly Review. Retrieved 2007-03-20.

- Is President Bush Destroying the American Empire? An Update on America's Inadvertent Empire Transcript of presentation by Robert Dujarric on April 14, 2004

- "On the Coming Decline and Fall of the US Empire". transnational.org. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- America and Taiwan, 1943-2004

Further reading

- Boot, Max (2002). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00721-X.

- Buchanan, Patrick (1999). A Republic, Not an Empire: Reclaiming America's Destiny. Regnery Pub. ISBN 0-89526-272-X.

- Card, Orson Scott (2006). Empire. TOR. ISBN 0-7653-1611-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Johnson, Chalmers (2000). Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire. ISBN 0-8050-6239-4.

- Johnson, Chalmers (2004). The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic. ISBN 0-8050-7004-4.

- Johnson, Chalmers (2007). Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic. ISBN 0-8050-7911-4.

- Odom, William (2004). America's Inadvertent Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300100698.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthours=ignored (help) - Perkins, John (2004). Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. ISBN 1-57675-301-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Tremblay, Rodrigue (2004). The New American Empire. Infinty publishing. ISBN 0-7414-1887-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Zepezauer, Mark (2002). Boomerang! : How Our Covert Wars Have Created Enemies Across the Middle East and Brought Terror to America. ISBN 1-56751-222-4.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)