Canadian Gaelic: Difference between revisions

m see WP:NOTBROKEN |

→Vocabulary: clarification of terminology/ poorly referenced material needs a more careful review |

||

| Line 69: | Line 69: | ||

{| |

{| |

||

| |

| |

||

*'''feirmeireachd''' ''verb'' to farm.<ref name="pei">{{cite web |last=Shaw |first=John |year=1987 |title=Gaelic in Prince Edward Island: A Cultural Remnant |url=http://www.upei.ca/iis/files/iis/rep_mk_1.pdf |publisher=''Gaelic Field Recording Project'' |accessdate=2006-09-12 }}</ref> |

*'''feirmeireachd''' ''verb'' to farm.<ref name="pei">{{cite web | last=Shaw | first=John |year=1987 | title=Gaelic in Prince Edward Island: A Cultural Remnant | url=http://www.upei.ca/iis/files/iis/rep_mk_1.pdf | publisher=''Gaelic Field Recording Project'' | accessdate=2006-09-12 }}</ref>. The term is likely a gaelicization of the English verb "to farm". |

||

*'''lodan''' ''noun'' a velvet offering pouch for church.<ref name="pei" /> |

*'''lodan''' ''noun'' a velvet offering pouch for church.<ref name="pei" /> |

||

*'''mogan''' ''noun'' |

*'''mogan''' ''noun'' a term which refers to a heavy ankle sock sold with a rubberized sole that was sold in Cape Breton four decades ago. The term also refers to a pull-on leg warmer for use when wearing the kilt in cold climates.<ref>{{cite web | author=unknown |year=1999 | title=Gaelic Placesnames of Nova Scotia | url=http://www.gaelic.ca/development/placenames.htm | publisher=''The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia'' | accessdate=2006-09-01 }}</ref> |

||

*'''pàirc-coillidh''' (or '''pàirce-choilleadh''') ''noun'' a wooded clearing burnt for planting crops, literally "forest park".<ref name="pei" /> |

*'''pàirc-coillidh''' (or '''pàirce-choilleadh''') ''noun'' a wooded clearing burnt for planting crops, literally "forest park".<ref name="pei" /> |

||

*'''dreag''' ''noun'' a [[will-o'-the-wisp]].<ref name="pei" /> |

*'''dreag''' ''noun'' a [[will-o'-the-wisp]].<ref name="pei" /> |

||

*'''sgeatadh''' ''verb'' |

*'''sgeatadh''' ''verb'' an gaelicization of the English verb "to skate". The fact that this term was used by some local speakers instead of "spèil" reflects the heavy reliance of Cape Breton speakers on English loan words when a proper Gaelic word was not known.<ref name="jst">{{cite book | author=Campbell, J.L. |year=1936 | title=Scottish Gaelic in Canada | url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-1283(193604)11%3A2%3C128%3ASGIC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-Z | publisher=''JSTOR'' | accessdate=2007-05-06 }}</ref> |

||

*'''seant''' (pl. '''seantaichean''') ''noun'' a cent.<ref name="jst" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*'''seant''' (pl. '''seantaichean''') ''noun'' a gaelicization of the English noun "cent".<ref name="jst" />. It should be noted that the term "dolair" is used in Canada and the U.S. instead of the word "nota", which refers to a British pound. "Sgillinn" is used both in Canada, the US, and GB to refer to coins. |

|||

*'''ponndadh''' ''verb'' beating (someone).<ref name="jst" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*'''ponndadh''' ''verb'' a gaelicization of the English verb "to pound". That this may have been used in Cape Breton instead of "bualadh" is evidence of the heavy reliance on English loan words.<ref name="jst" /> |

|||

| |

| |

||

*'''trì sgillinn''' ''phrasal noun'' a nickel. (literally |

*'''trì sgillinn''' ''phrasal noun'' a nickel. (literally “three [[Penny Scots|pence]]”).<ref name="jst" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*''' |

*'''sia sgillinn''' ''phrasal noun'' a dime. (literally “six pence”).<ref name="jst" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

*''' |

*'''tastan''' ''phrasal noun'' twenty cents. (literally “a shilling”).<ref name="jst" /> |

||

*'''stòr''' ''noun'' a shop (store).<ref name="jst" /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

*'''stòr''' ''noun'' a gaelicization of the English noun "store". Although the word stòr does refer to a storage building as well as wealth, the Gaelic term "bùth" is far more common among Gaelic speakers in Cape Breton today.<ref name="jst" /> |

|||

*'''taigh-obrach''' ''noun'' workhouse (penitentiary).<ref name="jst" /> |

*'''taigh-obrach''' ''noun'' workhouse (penitentiary).<ref name="jst" /> |

||

*'''bangaid''' ''noun'' a banquet.<ref name="jst" /> |

*'''bangaid''' ''noun'' a banquet.<ref name="jst" /> |

||

*'''Na Machraichean Mòra''' ''noun'' The Canadian Prairies.<ref name="jst" /> |

*'''Na Machraichean Mòra''' ''noun'' The Canadian Prairies.<ref name="jst" /> |

||

*'''buna-bhuachaille''' ''noun'' [[common loon]].<ref name="jst">{{cite book |author=MacNeil, Joe Neil |year=2007 |title=Cape |

*'''buna-bhuachaille''' ''noun'' [[common loon]].<ref name="jst">{{cite book | author=MacNeil, Joe Neil |year=2007 | title=Cape BReton Gaelic Folklore Collection | url=http://gaelstream.stfx.ca/gsdl/cgi-bin/library.exe?e=d-01000-00---0capebret--00-1--0-10-0---0---0prompt-10---4-------0-1l--11-en-50---20-about---00-3-1-00-0011-1-0utfZz-8-00&a=d&c=capebret&cl=CL1.1.92 | publisher=''St Francis Xavier University'' | accessdate=2007-06-02 }}</ref> |

||

|} |

|} |

||

Revision as of 22:13, 29 March 2010

| Canadian Gaelic | |

|---|---|

| A' Ghàidhlig Chanadach | |

| Pronunciation | əˈɣaːlɪkʲ ˈxanət̪əx |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | limited to Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia; scattered traditional speakers in mainland Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland & Labrador (Codroy Valley), Ontario (Glengarry, Stormont, Bruce and Grey Counties), The Red River Valley, Assiniboia and The Northwest. |

Native speakers | ca. 2000[1] |

Indo-European

| |

| Latin alphabet (Gaelic variant) | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gd |

| ISO 639-2 | gla |

| ISO 639-3 | gla |

| |

Canadian Gaelic or Cape Breton Gaelic (Scottish Gaelic: A' Ghàidhlig Chanadach, A' Ghàidhlig Chanèideanach, Gàidhlig Cheap Bhreatainn), locally just Gaelic or The Gaelic) refers to the dialects of Scots Gaelic that have been spoken continuously for more than 200 years on Cape Breton Island and in isolated enclaves on the Nova Scotia mainland. To a lesser extent the language is also spoken on nearby Prince Edward Island, Glengarry County in present-day Ontario and by emigrant Gaels living in major Canadian cities such as Toronto. At its peak in the mid-19th century, Gaelic, considered together with the closely related Irish language, was the third most spoken language in Canada after English and French.[2] The language has sharply declined since that period, however, and is now nearly extinct. Recently, efforts have been made to revitalize the language.

History

Early speakers

In 1621 King James VI of Scotland allowed privateer William Alexander to establish the first Scottish colony overseas. The group of Highlanders – all of whom were Gaelic-speaking – settled at what is presently known as Port Royal, on the western shore of Nova Scotia. Within a year the colony had failed. Subsequent attempts to relaunch it were cancelled when in 1631 the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye returned Nova Scotia to French rule.[3]

Almost a half-century later, in 1670, the Hudson's Bay Company was given exclusive trading rights to all North American lands draining into Hudson Bay – about 3.9 million km² (1.5 million sq mi – an area larger than India). Many of the traders were Orcadians and Scottish Highlanders, the latter of whom brought Gaelic to the interior. Those who intermarried with the local First Nations people passed on their language, with the effect that by the mid-1700s there existed a sizeable population of Métis traders with Scottish and aboriginal ancestry, and command of spoken Gaelic.[4]

Settlement

Cape Breton remained the property of France until 1758 (although mainland Nova Scotia had belonged to Britain since 1713) when Fortress Louisbourg fell to the British, followed by the rest of New France in the ensuing Battle at the Plaines d'Abraham. As a result of the conflict Highland regiments who fought for the British secured a reputation for tenacity and combat prowess.[2] In turn the countryside itself secured a reputation among the Highlanders for its size, beauty, and wealth of natural resources.[5]

They would remember Canada when in 1762 the earliest of the Fuadaich nan Gàidheal (Scottish Highland Clearances) forced many Gaelic families off their ancestral lands. The first ship loaded with Hebridean colonists arrived on "St.-John's Island" (Prince Edward Island) in 1770, with later ships following in 1772, and 1774.[2] In 1773 a ship named "The Hector" landed in Pictou, Nova Scotia, with 169 settlers mostly originating from the Isle of Skye.[6] In 1784 the last barrier to Scottish settlement – a law restricting land-ownership on Cape Breton Island – was repealed, and soon both PEI and Nova Scotia were predominantly Gaelic-speaking.[7] It is estimated more than 50,000 Gaelic settlers immigrated to Nova Scotia and Cape Breton Island between 1815 and 1870.[2]

With the end of the American War of Independence, immigrants newly arrived from Scotland would soon be joined by Loyalist emigrants escaping persecution from American Partisans. These settlers arrived on a mass scale at the arable lands of British North America, with large numbers settling in Glengarry County in present-day Ontario, and in the Eastern Townships of Quebec.[2]

Red River colony

In 1812 Lord Selkirk of Scotland obtained 300,000 square kilometres (120,000 sq mi) to build a colony at the forks of the Red River, in what would become Manitoba. With the help of his employee and friend, Archibald McDonald, Selkirk sent over 70 Scottish settlers, many of whom spoke only Gaelic, and had them establish a small farming colony there. The settlement soon attracted local First Nations groups, resulting in an unprecedented interaction of Scottish (Lowland, Highland, and Orcadian), English, Cree, French, Ojibwe, Saulteaux, and Métis traditions all in close contact.[8]

In the 1840s Toronto Anglican priest Dr John Black was sent to preach to the settlement, but "his lack of the Gaelic was at first a grievous disappointment" to parishioners.[9] With continuing immigration the population of Scots colonists grew to more than 300, but by the 1860s the French-Métis outnumbered the Scots, and tensions between the two groups would prove a major factor in the ensuing Red River Rebellion.[4]

The continuing association between the Selkirk colonists and surrounding First Nations groups evolved into a unique contact language. Used primarily by the Anglo- and Scots-Métis traders, the "Red River Dialect" or Bungee was a mixture of Gaelic and English with many terms borrowed from the local native languages. Whether the dialect was a trade pidgin or a fully developed mixed language is unknown. Today the Scots-Métis have largely been absorbed by the more dominant French-Métis culture, and the Bungee dialect is most likely extinct.

Nineteenth century

By 1850 Gaelic was the third most-common mother tongue in British North America after English and French, and is believed to have been spoken by more than 200,000 British North Americans at that time.[7] A large population who spoke the related Irish Gaelic immigrated to Scots Gaelic communities and to Irish settlements in Newfoundland. In PEI and Cape Breton there were large areas of Gaelic monolingualism,[7] and communities of Gaelic-speakers had established themselves in northeastern Nova Scotia (around Pictou and Antigonish); in Glengarry, Stormont, Grey, and Bruce Counties in Ontario; in the Codroy Valley of Newfoundland; in Winnipeg, Manitoba; and Eastern Quebec.[2]

At the time of Confederation in 1867 the most common mother tongue among the Fathers of Confederation was Gaelic.[10] In 1890, Thomas Robert McInnes, an independent Senator from British Columbia (born Lake Ainslie, Cape Breton Island) tabled a bill entitled "An Act to Provide for the Use of Gaelic in Official Proceedings."[7] He cited the ten Scottish and eight Irish senators who spoke Gaelic, and 32 members of the House of Commons who spoke either Scottish or Irish Gaelic. The bill was defeated 42–7.[2] Despite the widespread disregard by government on Gaelic issues, records exist of at least one criminal trial conducted entirely in Gaelic, c.1880–1900 in Baddeck, and presided over by Chief Justice Seumas Mac Dhòmhnaill.[7]

Linguistic features

The phonology of Canadian Gaelic has diverged in several ways from the standard Gaelic spoken in Scotland.[11] Gaelic terms unique to Canada exist, though research on the exact number is deficient. The language has also had a considerable and well-known effect on Cape Breton English.

Phonology

- l̪ˠ → w

- The most common Canadian Gaelic shibboleth, where [[dark l|broad /l̪ˠ/]] is pronounced as [w]. This form was well-known in Western Scotland where it was called the glug Eigeach ("Eigg cluck"), for its putative use among speakers from the Isle of Eigg.[11]

- n̪ˠ → m

- n̪ˠ → w

- This form is limited mostly to the plural ending -annan, where the -nn- sequence is pronounced as [w].[11]

- r → ʃ

- This change occurs frequently in many Scotland dialects when "r" is realized next to specific consonants; however such conditions are not necessary in Canadian Gaelic, where "r" is pronounced [ʃ] regardless of surrounding sounds.[11]

Vocabulary

|

|

Gaelic in Nova Scotia English

- boomaler noun a boor, oaf, bungler.

- sgudal noun garbage (sgudal).

- skiff noun a deep blanket of snow covering the ground. (from sguabach or sgiobhag).[11]

Arts and culture

A. W. R. MacKenzie founded the Nova Scotia Gaelic College at St Ann's in 1939. St Francis Xavier University in Antigonish has a Celtic Studies department with Gaelic-speaking faculty members, and is the only such department outside Scotland to offer four full years of Scottish Gaelic instruction.[7] Eòin Baoideach of Antigonish published the monthly Gaelic magazine An Cuairtear Òg Gaelach ("The Gaelic Tourist") around 1851.[2] The world's longest-running Gaelic periodical Mac Talla (Echo), was printed by Eòin G. MacFhionghain for eleven years between 1892 and 1904, in Sydney.[7] Eòin and Seòras MacShuail, believed to be the world's only black speakers of Goidelic languages, were born in Cape Breton and in adulthood became friends with Rudyard Kipling, who in 1896 wrote Captains Courageous, which featured an isolated Gaelic-speaking African-Canadian cook originally from Cape Breton.[15]

Many English-speaking artists of Canadian Gaelic heritage have featured Canadian Gaelic in their works, among them Alistair MacLeod (No Great Mischief ), Ann-Marie MacDonald (Fall on Your Knees ), and D.R. MacDonald (Cape Breton Road ). Gaelic singer Mary Jane Lamond has released several albums in the language, including the 1997 hit Hòro Ghoid thu Nighean, ("Jenny Dang the Weaver"). Cape Breton fiddling is a unique tradition of Gaelic and Acadian styles, known in fiddling circles worldwide.

Several Canadian schools use the "Gael" as a mascot, the most prominent being Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario. The school cheer of Queen's University is "Oilthigh na Bànrighinn a' Bhànrighinn gu bràth!" ("The College of the Queen forever!"), and is traditionally sung after scoring a touchdown in football matches. The university's team is nicknamed the Golden Gaels.

The Gaelic character of Nova Scotia has influenced that province's industry and traditions. Glen Breton Rare is the world's only single malt whisky made outside of Scotland, in Cape Breton. Gaelic settlers in Windsor adapted the popular Gaelic sport shinty (shinny) to be played on ice wearing skates, the precursor to modern ice hockey[citation needed].

The first Gaelic language film to be made in North America, Faire Chaluim MhicLeòid ("The Wake of Calum MacLeod") is a six-minute short filmed in Cape Breton.[16]

Reasons for decline

Despite the long history of Gaelic in Canada, the fluent population started to decline after 1850. This drop was a result of prejudice (both from outside, and from within the Gaelic community itself), aggressive dissuasion in school and government, and the perceived prestige of English.

Gaelic has faced widespread prejudice in Great Britain for generations, and those feelings were easily transposed to British North America.[17] In 1868 the Scottish-American Journal mockingly reported that "...the preliminary indispensables for acquiring Gaelic are: swallowing a neat assortment of nutmeal-graters, catching a chronic bronchitis, having one nostril hermetically sealed up, and submitting to a dislocation of the jaw."[17]

That Gaelic had not received official status in its homeland made it easier for Canadian legislators to disregard the concerns of domestic speakers. Legislators questioned why "privileges should be asked for Highland Scotchmen in [the Canadian Parliament] that are not asked for in their own country?".[7] Politicians who themselves spoke the language held opinions that would today be considered misinformed; Lunenburg Senator Henry A. N. Kaulbach, in response to Thomas Robert McInnes's Gaelic bill, described the language as only "well suited to poetry and fairy tales."[7] The belief that certain languages had inherent strengths and weaknesses was typical in the 19th century, but has been wholly refuted by modern linguistics.

Around 1880 Am Bàrd Mac Dhiarmaid from The North Shore, wrote An Té a Chaill a' Ghàidhlig (The Woman who Lost her Gaelic), a humorous song recounting the growing phenomenon of Gaels shunning their mother-tongue.[18]

|

Chuir mi fàilte orr' gu càirdeil: |

I welcomed her with affection: |

With the outbreak of World War II the Canadian government attempted to prevent the use of Gaelic on public telecommunications systems. The government believed Gaelic was used by subversives affiliated with Ireland, a neutral country perceived by some to be tacit supporters of the Nazis.[2] In Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton where the Gaelic language was strongest, it was actively discouraged in schools with corporal punishment. Children were beaten with the maide-crochaidh (en: hanging stick) if caught speaking Gaelic.[7]

Job opportunities for monolingual Gaels were few and restricted to the dwindling Gaelic-communities, compelling most into the mines or the fishery. Many saw English fluency as the key to success, and for the first time in Canadian history Gaelic-speaking parents were teaching their children to speak English en masse. The sudden stop of the Gaelic tradition-bearing bho ghlùin gu glùin ("from knee to knee"), caused by shame and prejudice, was the immediate cause of the drastic decline in Gaelic fluency in the Twentieth century.[7]

Ultimately the population dropped from a peak of 200,000 in 1850, to 80,000 in 1900, to 30,000 in 1930 and 500–1,000 today.[2] There are no longer entire communities of Canadian Gaelic-speakers, although traces of the language and pockets of speakers are relatively commonplace on Cape Breton, and especially in traditional strongholds like Christmas Island, The North Shore, and Baddeck.

Outlook and development

The last fluent Gaelic-speaker in Ontario, descended from the original settlers of Glengarry County, died in 2001.[19]

The oft-quoted statistic that "Scots Gaelic is spoken by more people in Cape Breton than in Scotland" is false. As of 2001 the official UK estimation is 58 652 Gaelic speakers; a figure possibly fifty times larger than the most optimistic Canadian statistic. Despite this, in the past twenty years interest in the language has grown considerably, in parallel to a similar build on the opposite side of the Atlantic.[20] Although not on the scale of the Scotland revival (for example there are not yet Canadian Gaelic-language immersion schools), several government initiatives have been undertaken to assess the current state of the language and language-community.

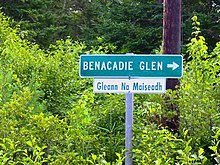

Government

A Gaelic Economic-impact Study completed by the Nova Scotia government in 2002 estimates that Gaelic generates over $23.5 million annually, with nearly 380 000 people attending approximately 2070 Gaelic events annually. This study inspired a subsequent report, The Gaelic Preservation Strategy, which polled the community's desire to preserve Gaelic while seeking consensus on adequate reparative measures. These two documents are watersheds in the timeline of Canadian Gaelic, representing the first concrete steps taken by the provincial government to recognize the language's decline and engage local speakers in reversing this trend. The documents recommend Community development, strengthening education, legislating road signs and publications, and building ties between the Gaelic community and other Nova Scotia "heritage language" communities (Mi'kmaq and Acadian French).

Increased ties were called for between Nova Scotia and Scotland, and the first such agreement, the Memorandum of Understanding, was signed in 2002.[21] The most recent step initiated by the government, and arguably the most significant, has been to create the Oifis Iomairtean na Gàidhlig (Office of Gaelic Affairs), the provincial department charged with promoting and engaging the province's Gaelic-speaking community. Established in December 2006, the mission of the Oifis is to collaborate with Nova Scotians in the renewal of Gaelic language and culture in the Province. One of the Office's first moves was to recruit a fluent Gaelic speaker from the Scottish Gàidhealtachd to live and work in Cape Breton and assist with ongoing language learning activities.

Education

Today over a dozen public institutions offer Gaelic courses, in addition to advanced programmes conducted at Cape Breton, St Francis Xavier and Saint Mary's Universities. Gaelic courses at public schools are increasingly popular. The Nova Scotia Highland Village offers a bilingual interpretation site, presenting Gaelic and English interpretation for visitors and offering programmes for the local community members. The Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts in St. Ann's offers Gaelic summer classes. In 2006, the privately funded Atlantic Gaelic Academy was established to teach the Gaelic language through both in-person classes at various locations, and live distance-learning classes.

Sponsored by local Gaelic organizations and societies, ongoing Gaelic language adult immersion classes involving hundreds of individuals are held in over a dozen communities in the province. These immersion programs focus on learning language through activity, props and repetition. Reading, writing and grammar are introduced after the student has had a minimum amount of exposure to hearing and speaking Gaelic through everyday contextualized activities. A recently established organization, FIOS (Forfhais, Innleachd, Oideachas agus Seirbhisean) focuses on the criteria and development of language learning programs at the community level using immersion methodologies. The grouping of immersion methodologies and the Gaelic arts in the immersion environment is referred to in Nova Scotia as Gàidhlig aig Baile.

Gaelic Place-names in Canada

|

Names in Cape Breton Island (Eilean Cheap Breatainn)

|

Names in mainland Nova Scotia (Tìr Mór na h-Albann Nuaidh)

Elsewhere in Canada

|

See also

|

|

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ Oifis Iomairtean na Gàidhlig/Office of Gaelic Affairs

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bumstead, J.M (2006). "Scots". Multicultural Canada. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Griffiths, N.E.S. (1992). "New Evidence on New Scotland, 1629". JSTOR Online Journal Archive. Retrieved 2006-11-02.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Dickason, Olive P (2006). "Métis". Multicultural Canada. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2003). "Bras d'Or Lake". Canoe Network. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2005). "Hector Festival". DeCoste Centre. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kennedy, Michael (2002). "Gaelic Economic-impact Study" (PDF). Nova Scotia Museum. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2006). "Red River Colony". The Canadian Encyclopædia. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Henderson, Anne Matheson (1968). "The Lord Selkirk Settlement at Red River". The Manitoba Historical Society. Retrieved 2006-08-30.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2006). "National Flag of Canada Day February 15". Department of Canadian Heritage. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f MacAulay, Donald (1996). "Festschrift for Professor D.S. Thomson" (PDF). Scottish Gaelic Studies 17, University of Aberdeen. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d Shaw, John (1987). "Gaelic in Prince Edward Island: A Cultural Remnant" (PDF). Gaelic Field Recording Project. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (1999). "Gaelic Placesnames of Nova Scotia". The Gaelic Council of Nova Scotia. Retrieved 2006-09-01.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Campbell, J.L. (1936). Scottish Gaelic in Canada. JSTOR. Retrieved 2007-05-06.

{{cite book}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) Cite error: The named reference "jst" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ unknown (2007). "Nova Scotia Quotations". Nova Scotia's Electronic Attic. Retrieved 2007-05-05.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2006). "N.S. Crew Set to Release Gaelic Short Film". CBC News. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Newton, Michael (2004). ""This Could Have Been Mine": Scottish Gaelic Learners in North America". Center for Celtic Studies, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2001). "MacEdward Leach and the Songs of Atlantic Canada". Memorial University of St John's, Nfld. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ McDonald, Rod (2001). "Alec McDonald". Electric Scotland. Retrieved 2006-04-26.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Kitson, Jill (2002). "Scotland's Gaelic Renaissance". Lingua Franca, Radio National. Retrieved 2007-03-03.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ unknown (2002). "Memorandum of Understanding". Nova Scotia Department of Tourism, Culture & Heritage. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Source?

References

- Oifis Iomairtean na Gàidhlig. Nova Scotia Provincial Office of Gaelic Affairs. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- Cainnt mo Mhàthar. Digital audio/visual archives of Canadian Gaels speaking Gaelic. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- Work through Time Audio and text archive of Cape Breton histories. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon Template:Fr icon (Mi'kmaq)

- Gaelic Economic-impact Study. Nova Scotia government report on Gaelic. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- Gaelic Preservation Strategy. Nova Scotia government strategy proposal. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- The Encyclopædia of Canada's Cultures: The Case of Gaelic

- Scottish Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts

- Gaelic Placenames in Nova Scotia

- Gaelic Placenames of Scotland and Canada

- Nova Scotia Gaelic Visual Archives

- Highland Village in Cape Breton

- Gaelic in Prince Edward Island

- Leugh Seo Gaelic Collection of the Cape Breton Library Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- Cape Breton Cèilidh Template:Fr icon Template:En icon

- St Francis Xavier University Gaelic Resources Template:Languageicon Template:Fr icon Template:En icon

- 'Se Ceap Breatainn Tìr Mo Ghràidh. Part One and Part Two. Scottish documentary on Canadian Gaelic-speaking community . Template:Languageicon

- Aiseirigh nan Gàidheal. Canadian Gaelic radio show. Template:Languageicon Template:En icon

- Mac-Talla. Canadian Gaelic newspaper, 540 issues. Template:Languageicon

- Fiosrachadh 'o'n Luchd-riaghlaidh mo Dheighinn Chanada. 1892. Book describing life in Canada, by Ùghdarras Pàrlamaid Chanada.Template:Languageicon

- Machraichean Mòra Chanada. 1907. Book describing immigration to the Canadian Prairies.Template:Languageicon

- White people, Indians, and Highlanders: tribal peoples and colonial encounters in Soctland and North America. Calloway, Colin Gordon.

- Speaking Canadian English: an informal account of the English language in Canada. Orkin, Mark M.

- Canadian History: Beginnings to Confederation. Taylor, Martin Brook & Owram, Doug.

- Language in Canada. Edwards, John R.