Affordable Care Act: Difference between revisions

Reverted to revision 399816123 by Barts1a; Hotair is not a reliable source, alos, neither are blogs and no original research. (TW) |

|||

| Line 356: | Line 356: | ||

==== Deficit impact ==== |

==== Deficit impact ==== |

||

{{See also|United States public debt}} |

{{See also|United States public debt}} |

||

The [[Congressional Budget Office|CBO]] initially estimated the legislation would reduce the deficit by $143 billion<ref name="CBO4872"/> over the first decade and by $1.2 trillion in the second decade;<ref name="CBO-Reid-Dec2009"/><ref name="CNN-Mar18">{{Cite news |

|||

| url = http://www.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/03/18/health.care.latest/index.html |

| url = http://www.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/03/18/health.care.latest/index.html |

||

| author = CNN |

| author = CNN |

||

| Line 362: | Line 362: | ||

| date = March 18, 2010 |

| date = March 18, 2010 |

||

| accessdate = May 12, 2010 |

| accessdate = May 12, 2010 |

||

}}.</ref> |

}}.</ref> the CBO has revised its estimates several times, initially projecting a savings of $132 billion, then $118 billion, and later $138 billion;<ref name="CBO-Reid-Mar2010">{{Cite web |

||

| url = http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11307/Reid_Letter_HR3590.pdf |

| url = http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11307/Reid_Letter_HR3590.pdf |

||

| title = H.R. 3590, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

| title = H.R. 3590, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act |

||

| Line 376: | Line 376: | ||

| date = March 18, 2010 |

| date = March 18, 2010 |

||

| accessdate = March 22, 2010 |

| accessdate = March 22, 2010 |

||

}}.</ref> however, for each estimate, CBO was required to accept assurances that the legislation would reduce Medicare payments, ignoring concurrent "doc fix" legislation that increased Medicare payments; combining the bills, CBO found "CBO estimates that enacting all three pieces of legislation would add |

|||

}}.</ref> The CBO estimates the cost of the first decade at $940 billion, $923 billion of which takes place during the final six years (2014–2019) when the benefits kick in.<ref name="CBO-Pelosi"/><ref name="RollCallCBO">{{Cite news |

|||

$59 billion to budget deficits over the 2010–2019 period."<ref>http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11376/RyanLtrhr4872.pdf</ref><ref>http://hotair.com/archives/2010/03/19/cbo-confirms-obamacare-with-doctor-fix-will-actually-add-billions-to-the-deficit/</ref><ref>http://www.nationalreview.com/critical-condition/55996/obamacare-s-cooked-books-and-doc-fix/james-c-capretta</ref><ref>http://www.investors.com/NewsAndAnalysis/Article/554579/201011221909/GOP-Might-Target-ObamaCare-As-Part-Of-A-Medicare-Doc-Fix.aspx</ref> Subject to the same exclusion, the CBO estimated the cost of the first decade at $940 billion, $923 billion of which takes place during the final six years (2014–2019) when the spending kicks in;<ref name="CBO-Pelosi"/><ref name="RollCallCBO">{{Cite news |

|||

| title = CBO: Health Care Overhaul Would Cost $940 Billion |

| title = CBO: Health Care Overhaul Would Cost $940 Billion |

||

| first = Steven |

| first = Steven |

||

| Line 385: | Line 386: | ||

| date = March 18, 2010 |

| date = March 18, 2010 |

||

| accessdate = March 22, 2010 |

| accessdate = March 22, 2010 |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> the CBO also projects revenue will exceed spending during these six years.<ref name="CBO-Pelosi2">{{Cite news |

||

| title = What does the health-care bill do in its first year? |

| title = What does the health-care bill do in its first year? |

||

| first = Ezra |

| first = Ezra |

||

| Line 407: | Line 408: | ||

==== Effect on national spending ==== |

==== Effect on national spending ==== |

||

The [[Congressional Budget Office]] (CBO) |

The [[United States Department of Health and Human Services]] reported that the bill would increase total national health expenditures by more than $200 billion from 2010-2019.<ref>http://www.politico.com/static/PPM110_091211_financial_impact.html</ref> Looking at the federal budget implications, the [[Congressional Budget Office]] (CBO) noted that among other things the bill would "substantially reduce the growth of Medicare’s payment rates for most services; impose an excise tax on insurance plans with relatively high premiums; and make various other changes to the federal tax code, Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs;"<ref name="CBO-Reid-Dec2009">{{Cite web | url = http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/108xx/doc10868/12-19-Reid_Letter_Managers_Correction_Noted.pdf | title = Correction Regarding the Longer-Term Effects of the Manager's Amendment to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | format = PDF | publisher = [[Congressional Budget Office]] | date = December 19, 2009 | accessdate = March 22, 2010}}</ref> however, CBO was required to exclude concurrent "doc fix" legislation that would increase Medicare payments by more than $200 billion from 2010-2019.<ref>http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11376/RyanLtrhr4872.pdf</ref><ref>http://hotair.com/archives/2010/03/19/cbo-confirms-obamacare-with-doctor-fix-will-actually-add-billions-to-the-deficit/</ref><ref>http://www.nationalreview.com/critical-condition/55996/obamacare-s-cooked-books-and-doc-fix/james-c-capretta</ref><ref>http://www.investors.com/NewsAndAnalysis/Article/554579/201011221909/GOP-Might-Target-ObamaCare-As-Part-Of-A-Medicare-Doc-Fix.aspx</ref> |

||

For the effect on health insurance premiums, the CBO referred<ref name="CBO-Reid-Dec2009"/>{{Rp|15}} to its November 2009 analysis<ref name=CBOPremiumEffect>CBO.(Nov 2009).[www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10781&type=1 An Analysis of Health Insurance Premiums Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act].</ref> and stated that the effects would "probably be quite similar" to that earlier analysis. That analysis forecasted that by 2016: for the nongroup market comprising 17% of the market, premiums per person would increase by 10 to 13% but that over half of these insureds would receive subsidies which would decrease the premium paid to "well below" premiums charged under current law; for the small group market 13% of the market, premiums would be impacted 1 to −3% and −8 to −11% for those receiving subsidies; for the large group market comprising 70% of the market, premiums would be impacted 0 to −3%, with insureds under high premium plans subject to excise taxes being charged −9 to −12%. The analysis was affected by various factors including increased benefits particularly for the nongroup markets, more healthy insureds due to the mandate, administrative efficiencies related to the health exchanges, and insureds under high premium plans reducing benefits in response to the tax.<ref name=CBOPremiumEffect/> |

For the effect on health insurance premiums, the CBO referred<ref name="CBO-Reid-Dec2009"/>{{Rp|15}} to its November 2009 analysis<ref name=CBOPremiumEffect>CBO.(Nov 2009).[www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10781&type=1 An Analysis of Health Insurance Premiums Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act].</ref> and stated that the effects would "probably be quite similar" to that earlier analysis. That analysis forecasted that by 2016: for the nongroup market comprising 17% of the market, premiums per person would increase by 10 to 13% but that over half of these insureds would receive subsidies which would decrease the premium paid to "well below" premiums charged under current law; for the small group market 13% of the market, premiums would be impacted 1 to −3% and −8 to −11% for those receiving subsidies; for the large group market comprising 70% of the market, premiums would be impacted 0 to −3%, with insureds under high premium plans subject to excise taxes being charged −9 to −12%. The analysis was affected by various factors including increased benefits particularly for the nongroup markets, more healthy insureds due to the mandate, administrative efficiencies related to the health exchanges, and insureds under high premium plans reducing benefits in response to the tax.<ref name=CBOPremiumEffect/> |

||

Revision as of 23:47, 2 December 2010

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)[1][2] is a federal statute that was signed into law in the United States by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. Along with the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 (signed into law on March 30, 2010), the Act is the product of the health care reform agenda of the Democratic 111th Congress and the Obama administration. The Congressional Budget Office estimated that the new law as amended would reduce the federal deficit by $143 billion over the first decade and in the decade after that by an amount equivalent in a broad range between one quarter percent and one-half percent of GDP.[3]

The law includes numerous health-related provisions to take effect over a four-year period, including prohibiting health insurers from denying coverage or refusing claims based on pre-existing conditions, expanding Medicaid eligibility, subsidizing insurance premiums, providing incentives for businesses to provide health care benefits, establishing health insurance exchanges, and support for medical research. The costs of these provisions are offset by a variety of taxes, such as taxes on indoor tanning and certain medical devices (excluding eyeglasses, contact lenses, hearing aids, and any other medical device which is determined to be of a type generally purchased by the general public at retail for individual use), and offset by cost savings such as improved fairness in the Medicare Advantage program relative to traditional Medicare.[4] There is also a tax penalty for citizens who do not obtain health insurance (unless they are exempt due to low income or other reasons).[5]

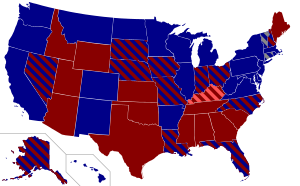

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act passed the Senate on December 24, 2009, by a vote of 60–39 with all Democrats and Independents voting for, and all Republicans voting against. It passed the House of Representatives on March 21, 2010, by a vote of 219–212, with all 178 Republicans and 34 Democrats voting against the bill. At the time of the vote, there were four vacancies in the House.

| |

| Long title | The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. |

|---|---|

| Acronyms (colloquial) | PPACA |

| Nicknames | Healthcare Reform |

| Enacted by | the 111th United States Congress |

| Effective | March 23, 2010 Specific provisions phased in through January 1, 2018 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 111–148 |

| Statutes at Large | 124 Stat. 119 thru 124 Stat. 1025 (906 pages) |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 | |

Legislative history

Background

| This article is part of a series on |

| Healthcare reform in the United States |

|---|

|

|

Health care reform was a major topic of discussion during the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries. As the race narrowed, attention focused on the plans presented by the two leading candidates, New York Senator Hillary Clinton and the eventual nominee, Illinois Senator Barack Obama. Each candidate proposed a plan to cover the approximately 45 million Americans estimated to go without health insurance at some point during each year. One point of difference between the plans was that Clinton's plan was to require all Americans to obtain coverage (in effect, an individual health insurance mandate), while Obama's was to provide a subsidy but not create a direct requirement.

During the general election campaign between Obama and the Republican nominee, Arizona Senator John McCain, Obama said that fixing health care would be one of his four priorities if he won the presidency.[6] After his inauguration, Obama announced to a joint session of Congress in February 2009 that he would begin working with Congress to construct a plan for health care reform.[7] On March 5, 2009, Obama formally began the reform process and held a conference with industry leaders to discuss reform and requested reform be enacted before the Congressional summer recess; but the reform was not passed by the requested date.[8] In July 2009, a series of bills were approved by committees within the House of Representatives.[9] Beginning June 17, 2009, and extending through September 14, 2009, three Democratic and three Republican Senate Finance Committee Members met for a series of 31 meetings to discuss the development of a health care reform bill. Over the course of the next three months, this group, Senators Max Baucus (D-Montana), Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), Kent Conrad (D-North Dakota), Olympia Snowe (R-Maine), Jeff Bingaman (D-New Mexico), and Mike Enzi (R-Wyoming), met for more than 60 hours, and the principles that they discussed became the foundation of the Senate's health care reform bill.[10] The meetings were held in public and broadcast by C-Span and can be seen on the C-Span web site [11] or at the Committee's own web site[12]. During the August 2009 congressional recess, many members went back to their districts and entertained town hall meetings to solicit public opinion on the proposals. During the summer recess, the Tea Party movement organized protests and many conservative groups and individuals targeted congressional town hall meetings to voice their opposition to the proposed reform bills.[8][13]

In response to the opposition, Obama delivered a speech to a joint session of Congress on health reform supporting the reform and again outlining his proposals.[14][15] On November 7, the House of Representatives passed the Affordable Health Care for America Act on a 220–215 vote and forwarded it to the Senate for passage.[8][16]

The Senate bill, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, bore similarities to a Republican healthcare reform proposal in 1993, the Health Equity and Access Reform Today Act of 1993;[17] a 1994 Republican proposal under the Consumer Choice Health Security Act was similar in that it contained an individual mandate.[18]

There were many threats made against members of Congress and many were assigned extra protection. [19][20][21] [22] [23][24] [24][25][26][27] [28][29][30][31] [19][32][33][34][23][35]

Senate

The Senate failed to take up debate on the House bill and instead took up H.R. 3590, a bill regarding housing tax breaks for service members.[36] As the United States Constitution requires all revenue-related bills to originate in the House,[37] the Senate took up this bill since it was first passed by the House as a revenue-related modification to the Internal Revenue Code. The bill was then used as the Senate's vehicle for their health care reform proposal, completely revising the content of the bill.[38] The bill as amended incorporated elements of earlier proposals that had been reported favorably by the Senate Health and Finance committees.

Passage in the Senate was temporarily blocked by a filibuster threat by Nebraska Senator Ben Nelson, who sided with the Republican minority. Nelson's support for the bill was won after it was amended to offer a higher rate of Medicaid reimbursement for Nebraska.[8] The compromise was derisively referred to as the "Cornhusker Kickback"[39] (and was later repealed by the reconciliation bill). On December 23, the Senate voted 60–39 to end debate on the bill, eliminating the possibility of a filibuster by opponents. The bill then passed by a party-line vote of 60–39 on December 24, 2009, with one senator (Jim Bunning) not voting.[40]

House

On January 19, 2010, Massachusetts Republican Scott Brown was elected to the Senate, giving the Republican minority enough votes to sustain a filibuster in the future.[8] Following Brown's Senate win, the fate of the health care reform was uncertain. White House Chief of Staff Rahm Emanuel argued for a less ambitious bill, while House Speaker Nancy Pelosi pushed back, dismissing Emanuel's scaled-down approach as "Kiddie Care".[41][42] Obama's siding with comprehensive reform and the news that Anthem Blue Cross in California intended to raise premium rates for its patients by as much as 39% gave him a new line of argument for reform.[41][42] Obama unveiled a health care reform plan of his own, drawing largely from the Senate bill. On February 22 he laid out a "Senate-leaning" proposal to consolidate the bills.[43] On February 25, he held a meeting with leaders of both parties urging passage of a reform bill.[8] The summit proved successful in shifting the political narrative away from the Massachusetts loss back to health care policy.[42]

The most viable option for the proponents of comprehensive reform was for the House to abandon its own health reform bill, the Affordable Health Care for America Act, and to instead pass the Senate's bill, and then pass amendments to it with a different bill allowing the Senate to pass the amendments via the reconciliation process.[41][44]

Initially, there were not enough supporters to pass the bill, thus requiring its proponents to negotiate with a group of pro-life Democrats, led by Congressman Bart Stupak. The group found the possibility of federal funding for abortion was substantive enough to cause their opposition to the bill. Instead of requesting inclusion of additional language specific to their abortion concerns in the bill, President Obama issued Executive Order 13535, reaffirming the principles in the Hyde Amendment. This concession won the support of Stupak and members of his group and assured passage of the bill.[45]

The House passed the bill with a vote of 219 to 212 on March 21, 2010, with 34 Democrats and all 178 Republicans voting against it.[46] The following day, Republicans introduced legislation to repeal the bill.[47] Obama signed the bill into law on March 23, 2010.[48]

Provisions

The Act is divided into 10 titles.[49]

The bill contains provisions that will go into effect immediately; on June 21, 2010 (90 days after enactment); on September 23, 2010 (six months after enactment); and provisions that will go into effect in 2014.[50][51]

Below are some of the key provisions of the bill. For simplicity, the amendments in the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 are integrated into this timeline.[52][53]

Effective at enactment

- The Food and Drug Administration is now authorized to approve generic versions of biologic drugs and grant biologics manufacturers 12 years of exclusive use before generics can be developed.[54]

- The Medicaid drug rebate for brand name drugs is increased to 23.1% (except the rebate for clotting factors and drugs approved exclusively for pediatric use increases to 17.1%), and the rebate is extended to Medicaid managed care plans; the Medicaid rebate for non-innovator, multiple source drugs is increased to 13% of average manufacturer price.[54]

- A non-profit Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute is established, independent from government, to undertake comparative effectiveness research.[54] This is charged with examining the "relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness" of different medical treatments by evaluating existing studies and conducting its own. Its 19-member board is to include patients, doctors, hospitals, drug makers, device manufacturers, insurers, payers, government officials and health experts. It will not have the power to mandate or even endorse coverage rules or reimbursement for any particular treatment. Medicare may take the Institute’s research into account when deciding what procedures it will cover, so long as the new research is not the sole justification and the agency allows for public input. [55] The bill forbids the Institute to develop or employ "a dollars per quality adjusted life year" (or similar measure that discounts the value of a life because of an individual’s disability) as a threshold to establish what type of health care is cost effective or recommended. This makes it different from the UK's National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence.

- Creation of task forces on Preventive Services and Community Preventive Services to develop, update, and disseminate evidenced-based recommendations on the use of clinical and community prevention services.[54]

- The Indian Health Care Improvement Act is reauthorized and amended.[54]

Effective June 21, 2010

- Adults with pre-existing conditions will be eligible to join a temporary high-risk pool, which will be superseded by the health care exchange in 2014.[51][56] To qualify for coverage, applicants must have a pre-existing health condition and have been uninsured for at least the past six months.[57] There is no age requirement.[57] The new program sets premiums as if for a standard population and not for a population with a higher health risk. Allow premiums to vary by age (4:1), geographic area, and family composition. Limit out-of-pocket spending to $5,950 for individuals and $11,900 for families, excluding premiums.[57][58][59] As at November 2010, enrollment in high risk pools, a temporary solution in the Act but a permanent solution in Republican alternative policy, is running behind the levels anticipated at this time. HHS had predicted that 375,000 people would be enrolled by November 2010 but the actual number by that time was only 8,011. [60]

Effective July 1, 2010

- The President will have established, within the Department of Health and Human Services, a council to be known as the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council to help begin to develop a National Prevention and Health Promotion Strategy. The Surgeon General shall serve as the Chairperson of the new Council.[61][62]

Effective September 23, 2010

- Insurance companies will be prohibited from imposing lifetime dollar limits on essential benefits, like hospital stays in new policies issued.[63]

- Dependents (children) will be permitted to remain on their parents' insurance plan until their 26th birthday,[64] and regulations implemented under the Act include dependents that no longer live with their parents, are not a dependent on a parent’s tax return, are no longer a student, or are married.[65][66]

- Insurers are prohibited from excluding pre-existing medical conditions (except in grandfathered individual health insurance plans) for children under the age of 19.[67][68]

- Insurers are prohibited from charging co-payments or deductibles for Level A or Level B preventive care and medical screenings on all new insurance plans.[69]

- Individuals affected by the Medicare Part D coverage gap will receive a $250 rebate, and 50% of the gap will be eliminated in 2011.[70] The gap will be eliminated by 2020.

- Insurers' abilities to enforce annual spending caps will be restricted, and completely prohibited by 2014.[51]

- Insurers are prohibited from dropping policyholders when they get sick.[51]

- Insurers are required to reveal details about administrative and executive expenditures.[51]

- Insurers are required to implement an appeals process for coverage determination and claims on all new plans.[51]

- Indoor tanning services are subjected to a 10% service tax.[51]

- Enhanced methods of fraud detection are implemented.[51]

- Medicare is expanded to small, rural hospitals and facilities.[51]

- Medicare patients with chronic illnesses must be monitored/evaluated on a 3 month basis for coverage of the medications for treatment of such illnesses.

- Non-profit Blue Cross insurers are required to maintain a loss ratio (money spent on procedures over money incoming) of 85% or higher to take advantage of IRS tax benefits.[51]

- Companies which provide early retiree benefits for individuals aged 55–64 are eligible to participate in a temporary program which reduces premium costs.[51]

- A new website installed by the Secretary of Health and Human Services will provide consumer insurance information for individuals and small businesses in all states.[51]

- A temporary credit program is established to encourage private investment in new therapies for disease treatment and prevention.[51]

Effective by January 1, 2011

- Insurers will be required to spend 85% of large-group and 80% of small-group and individual plan premiums (with certain adjustments) on health care or to improve health-care quality, or return the difference to the customer as a rebate.[71]

- The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is responsible for developing the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation and overseeing the testing of innovative payment and delivery models.[72]

- Flexible spending accounts, healthcare reimbursement arrangements and health savings accounts cannot be used to pay for over the counter drugs, purchased without a prescription, except for insulin.[73]

Effective by January 1, 2012

- Employers must disclose the value of the benefits they provided beginning in 2012 for each employee's health insurance coverage on the employees' annual Form W-2's[74]. This requirement was originally to be effective January 1, 2011 but was postponed by IRS Notice 2010-69 on October 23, 2010.[75]

- New tax reporting changes come into effect which aims to prevent tax evasion by corporations. The provision is expected to raise $17 billion over 10 years.[76] Under the existing law, businesses have to notify the IRS of certain payments to individuals for certain services or property[77][78] over a reporting threshold of $600: from this date the law is changed so that payments to corporations must also be reported.[79][80] There are a number of exceptions, for example: personal payments, payments for merchandise, telephone, freight, storage, payments of rent to real estate agents are exempt from reporting.[77] The amendments made by this section of the bill (SEC. 9006) shall apply to payments made by businesses after December 31, 2011.[78]

Effective by January 1, 2013

- Self-employment and wages of individuals above $200,000 annually (or of families above $250,000 annually) will be subject to an additional tax of 0.5%.[81]

Effective by January 1, 2014

- Insurers are prohibited from discriminating against or charging higher rates for any individuals based on pre-existing medical conditions.[51][82]

- Insurers are prohibited from establishing annual spending caps.[51]

- Expand Medicaid eligibility; individuals with income up to 133% of the poverty line qualify for coverage, including adults without dependent children.[83][84]

- Two years of tax credits will be offered to qualified small businesses. In order to receive the full benefit of a 50% premium subsidy, the small business must have an average payroll per full time equivalent ("FTE") employee, excluding the owner of the business, of less than $25,000 and have fewer than 11 FTEs. The subsidy is reduced by 6.7% per additional employee and 4% per additional $1,000 of average compensation. A 16 FTE firm with a $35,000 average salary would be entitled to a 10% premium subsidy.

- Impose a $2000 per employee tax penalty on employers with more than 50 employees who do not offer health insurance to their full-time workers (as amended by the reconciliation bill).[85]

- Set a maximum of $2000 annual deductible for a plan covering a single individual or $4000 annual deductible for any other plan (see 111HR3590ENR, section 1302). These limits can be increased under rules set in section 1302.

- Impose an annual penalty of $95, or up to 1% of income, whichever is greater, on individuals who do not secure insurance; this will rise to $695, or 2.5% of income, by 2016. This is an individual limit; families have a limit of $2,085.[83][86] Exemptions to the fine in cases of financial hardship or religious beliefs are permitted.[83]

- Under the CLASS Act provision, creates a new voluntary long-term care insurance program; enrollees who have paid premiums into the program and become eligible (due to disability or chronic illnesses) would receive benefits that help pay for assistance in the home or in a facility.[87]

- Employed individuals who pay more than 9.5% of their income on health insurance premiums will be permitted to purchase insurance policies from a state-controlled health insurance option.[50] If the employer provides an employer sponsored plan but the individual earns less than 400 per cent of the Federal Poverty level and could qualify for a government subsidy, the employee is entitled to obtain a "free choice voucher" from the employer of equivalent value to the employer's offering which can be spent in the exchange to buy a subsidized policy of his own choosing.[88]

- Pay for new spending, in part, through spending and coverage cuts in Medicare Advantage, slowing the growth of Medicare provider payments (in part through the creation of a new Independent Payment Advisory Board), reducing Medicare and Medicaid drug reimbursement rate, cutting other Medicare and Medicaid spending.[53][89]

- Revenue increases from a new $2,500 limit on tax-free contributions to flexible spending accounts (FSAs), which allow for payment of health costs.[90]

- Chain restaurants and food vendors with 20 or more locations are required to display the caloric content of their foods on menus, drive-through menus, and vending machines. Additional information, such as saturated fat, carbohydrate, and sodium content, must also be made available upon request.[91]

- Establish health insurance exchanges, and subsidization of insurance premiums for individuals with income up to 400% of the poverty line, as well as single adults.[84][92][93] Section 1401(36B) of PPACA explains that the subsidy will be provided as an advanceable, refundable tax credit[94] and gives a formula for its calculation.[95] Refundable tax credit is a way to provide government benefit to people even with no tax liability[96] (example: Child Tax Credit). According to White House and Congressional Budget Office estimates, in 2016 the income-based premium caps for a "silver" healthcare plan for family of four would be the following:[97][98]

| Income | Premium Cap as a Share of Income | Middle of Income Range (family of 4)a | Avg Annual Enrollee Premium | Premium Subsidy (share of premium) | Avg Cost-Sharing Subsidy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100–150% of federal poverty level | 2.1–4.7% of income | $30,000 | $600 | 96% | $3,300 |

| 150–200% of federal poverty level | 4.7–6.5% of income | $42,000 | $2,400 | 83% | $1,800 |

| 200–250% of federal poverty level | 6.5–8.4% of income | $54,000 | $4,000 | 72% | 0 |

| 250–300% of federal poverty level | 8.4–10.2% of income | $66,000 | $6,100 | 57% | 0 |

| 300–350% of federal poverty level | 10.2% of income | $78,000 | $9,200 | 44% | 0 |

| 350–400% of federal poverty level | 10.2% of income | $90,100 | $14,100 | 35% | 0 |

- Members of Congress and their staff will only be offered health care plans through the exchange or plans otherwise established by the bill (instead of the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program that they currently use).[100]

- A new excise tax goes into effect that is applicable to pharmaceutical companies and is based on the market share of the company; it is expected to create $2.5 billion in annual revenue.[86]

- Most medical devices become subject to a 2.3% excise tax collected at the time of purchase. (Reduced by the reconciliation act to 2.3% from 2.6%) [101]

- Health insurance companies become subject to a new excise tax based on their market share; the rate gradually raises between 2014 and 2018 and thereafter increases at the rate of inflation. The tax is expected to yield up to $14.3 billion in annual revenue.[86]

- The qualifying medical expenses deduction for Schedule A tax filings increases from 7.5% to 10% of earned income.[102]

Effective by January 1, 2017

- A state may apply to the Secretary of Health & Human Services for a waiver of certain sections in the law, with respect to that state, such as the individual mandate,[103] provided that the state develops a detailed alternative that "will provide coverage that is at least as comprehensive" and "at least as affordable" for "at least a comparable number of its residents" as the waived provisions. The decision of whether to grant this waiver is up to the Secretary (who must annually report to Congress on the waiver process) after a public comment period.[104]

Effective by 2018

- All existing health insurance plans must cover approved preventive care and checkups without co-payment.[51]

- A new 40% excise tax on high cost ("Cadillac") insurance plans is introduced. The tax (as amended by the reconciliation bill)[105] is on the cost of coverage in excess of $27,500 (family coverage) and $10,200 (individual coverage), and it is increased to $30,950 (family) and $11,850 (individual) for retirees and employees in high risk professions. The dollar thresholds are indexed with inflation; employers with higher costs on account of the age or gender demographics of their employees may value their coverage using the age and gender demographics of a national risk pool.[86][106]

Impact

Public policy impact

Deficit impact

The CBO initially estimated the legislation would reduce the deficit by $143 billion[3] over the first decade and by $1.2 trillion in the second decade;[107][108] the CBO has revised its estimates several times, initially projecting a savings of $132 billion, then $118 billion, and later $138 billion;[109][110] however, for each estimate, CBO was required to accept assurances that the legislation would reduce Medicare payments, ignoring concurrent "doc fix" legislation that increased Medicare payments; combining the bills, CBO found "CBO estimates that enacting all three pieces of legislation would add $59 billion to budget deficits over the 2010–2019 period."[111][112][113][114] Subject to the same exclusion, the CBO estimated the cost of the first decade at $940 billion, $923 billion of which takes place during the final six years (2014–2019) when the spending kicks in;[110][115] the CBO also projects revenue will exceed spending during these six years.[116]

The CBO generally does not provide cost estimates beyond the 10-year budget projection period because of the great degree of uncertainty involved in the data. It decided to do so in this case at the request of lawmakers. It predicted deficit reduction around a broad range of one-half percent of GDP over the 2020s while cautioning that "a wide range of changes could occur".[117] Uwe Reinhardt, a Health economist at Princeton, wrote that "The rigid, artificial rules under which the Congressional Budget Office must score proposed legislation unfortunately cannot produce the best unbiased forecasts of the likely fiscal impact of any legislation", but went on to say "But even if the budget office errs significantly in its conclusion that the bill would actually help reduce the future federal deficit, I doubt that the financing of this bill will be anywhere near as fiscally irresponsible as was the financing of the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003."[118] Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former CBO director who served during the George W. Bush adminstration, opined that the bill would increase the deficit by $562 billion.[119]

David Walker, former U.S. Comptroller General now working for The Peter G. Peterson Foundation, has stated that the CBO estimates are not likely to be accurate, because it is based on the assumption that Congress is going to do everything they say they're going to do.[120] On the other hand, a Center on Budget and Policy Priorities analysis said that Congress has a good record of implementing Medicare savings. According to their study, Congress implemented the vast majority of the provisions enacted in the past 20 years to produce Medicare savings.[121][122]

Change in number of uninsured

According to Congressional Budget Office estimates, the number of uninsured residents will drop from current levels by 32 million people. This leaves 23 million residents who will still lack insurance in 2019 after the bill's provisions have all taken effect.[123] Among the people in this group will be:

- Illegal immigrants, estimated at almost a third of the 23 million, will be ineligible for insurance subsidies and Medicaid.[123]

- Those who do not enroll in Medicaid despite being eligible.[124]

- Those who are not otherwise covered and opt to pay the annual penalty (2.5% of income, $695 for individuals, or a maximum of $2,250 per family) instead of purchasing (presumably more expensive) insurance; this might be mostly younger and single Americans.[124]

- Those whose insurance coverage would cost more than 8% of household income; they are exempt from paying the annual penalty.[124]

Effect on national spending

The United States Department of Health and Human Services reported that the bill would increase total national health expenditures by more than $200 billion from 2010-2019.[125] Looking at the federal budget implications, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) noted that among other things the bill would "substantially reduce the growth of Medicare’s payment rates for most services; impose an excise tax on insurance plans with relatively high premiums; and make various other changes to the federal tax code, Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs;"[107] however, CBO was required to exclude concurrent "doc fix" legislation that would increase Medicare payments by more than $200 billion from 2010-2019.[126][127][128][129]

For the effect on health insurance premiums, the CBO referred[107]: 15 to its November 2009 analysis[130] and stated that the effects would "probably be quite similar" to that earlier analysis. That analysis forecasted that by 2016: for the nongroup market comprising 17% of the market, premiums per person would increase by 10 to 13% but that over half of these insureds would receive subsidies which would decrease the premium paid to "well below" premiums charged under current law; for the small group market 13% of the market, premiums would be impacted 1 to −3% and −8 to −11% for those receiving subsidies; for the large group market comprising 70% of the market, premiums would be impacted 0 to −3%, with insureds under high premium plans subject to excise taxes being charged −9 to −12%. The analysis was affected by various factors including increased benefits particularly for the nongroup markets, more healthy insureds due to the mandate, administrative efficiencies related to the health exchanges, and insureds under high premium plans reducing benefits in response to the tax.[130]

Surgeon Atul Gawande has noted that bill contains a variety of pilot programs that may have a significant impact on cost and quality over the long-run, although these have not been factored into CBO cost estimates. He stated these pilot programs cover nearly every idea healthcare experts advocate, except malpractice/tort reform. He argued that a trial and error strategy, combined with industry and government partnership, is how the U.S. overcame a similar challenge in the agriculture industry in the early 20th century.[131]

The Business Roundtable, an association of CEOs, commissioned a report from the consulting company Hewitt Associates that found that the legislation "could potentially reduce that trend line by more than $3,000 per employee, to $25,435" with respect to insurance premiums. It also stated that the legislation "could potentially reduce the rate of future health care cost increases by 15% to 20% when fully phased in by 2019". The group cautioned that this is all assuming that the cost-saving government pilot programs both succeed and then are wholly copied by the private market, which is uncertain.[132]

The Office of the Actuary at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services released a report in April 2010 saying that the PPACA would increase the number of Americans with health insurance coverage but would also increase projected spending by approximately 1% over 10 years. The report also cautioned that the increases could be larger, because the Medicare cuts in the law may be unrealistic and unsustainable, forcing lawmakers to roll them back. The report projected that Medicare cuts could put nearly 15% of hospitals and other institutional providers into debt, "possibly jeopardizing access" to care for seniors.[133][134] The Bill was described as "the federal government’s biggest attack on economic inequality since inequality began rising more than three decades ago".[135]

After the bill was signed, AT&T, Caterpillar, Verizon, and John Deere issued financial reports showing large current charges against earnings, up to US$1 billion in the case of AT&T, attributing the additional expenses to tax changes in the new health care law.[136] Under the new law as of 2013 companies can no longer deduct a subsidy for prescription drug benefits granted under Medicare Part D.[137]

Political impact

Public opinions and views

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, and Obama's plans for health care reform in general, is often nicknamed "Obamacare".[138] The term was usually used pejoratively, but some supporters of the act suggested after being passed that it be embraced and used positively.[139]

Of ten polls conducted just prior to the passage of the bill, none found a majority in support. Three found about equal opposition and support, five found a plurality expressing opposition, and two found a majority expressing opposition.[140] The differences could have been caused by context and phrasing of the questions; for example, support for mandates was 56 to 59% when subsidies were mentioned for those who could not afford insurance but 28% when penalties were mentioned.[140] Some ideas which showed majority support, such as purchasing drugs from Canada, limiting malpractice awards, and reducing the age to qualify for Medicare, were not enacted.[140]

In the three days preceding the health care reform bill vote in the House (March 19–21), a CNN poll of 1,030 adult Americans found that 59% opposed the legislation while 39% supported it. Further breakdown showed that 43% opposed the bill because it was too liberal, 13% opposed it because it was not liberal enough, and the remaining 39% supported the bill.[141] Of the same group of respondents, 56% said the bill "gives the government too much involvement in health care", while 28% said it gives the government a "proper role" and 16% said the government's role would be "inadequate". On costs, 62% believed the bill "increases the amount of money they personally spend on health care", while 37% believed their costs would either remain the same or go down. On the fiscal impact of the bill, 70% believed it would lead to higher deficits, while 17% believed there would be no change and 12% said deficits would decrease.[141] In another poll prior to passage, a March 22 USA Today/Gallup poll of 1,005 adults found that 49% viewed the legislation as "a good thing" or otherwise reacted positively, while about 40% viewed it badly or otherwise reacted negatively. Opinions were found to be starkly divided by age, with a solid majority of seniors opposing the bill and a solid majority of those younger than 40 in favor.[142]

After the bill was passed, polls from CBS News,[143] CNN,[144] and Gallup[145] reported that Obama's approval rating improved. On the other side, a Rasmussen poll after passage reported that 55% of likely voters favored repealing the bill, and a Rasmussen poll in Florida found that 54% of likely voters favored Attorney General Bill McCollum's lawsuit to prevent the legislation's implementation.[146] On April 2, CBS reported that 34% of Americans approved of President Obama's handling of health care and 32% approved of the health care bill signed into law.[147]

In August 2010, citing what she called "a great deal of confusion about what is in [the reform law] and what isn’t" due to "misinformation given on a 24/7 basis", Health and Human Services Secretary Kathleen Sebelius said that the Obama administration has "a lot of reeducation to do".[148]

In terms of impact on the 2010 election cycle, Politico reported on September 5 that five House Democrats had run political ads highlighting their "no" votes on the bill, while there had not been any political ads highlighting a "yes" vote since April, when Harry Reid ran one.[149]

Several health insurers stated that they are seeking rate increases as a direct result of the law. The rate increases apply mostly to employees of small businesses (less than 50 people) and to people who buy plans as individuals. Some customers could experience rate increases of over 20 percent. The White House stated that insurers had already planned to raise rates and were using the bill as an excuse.[150]

Impact on child-only policies

In September 2010 some insurance companies announced that in response to the law, they would end the issuance of new child-only policies.[151][152] Kentucky Insurance Commissioner Sharon Clark said the decision by insurers to stop offering such policies was a violation of state law and ordered insurers to to offer an open enrollment period in January 2011 for Kentuckians under 19.[153]

Legal challenges

Challenges by states

Organizations and lawmakers who opposed the passage of the bill threatened to take legal action against it upon its passage.[154] The target of the threatened lawsuits were several key provisions of the bill. Opponents claimed that fining individuals for failing to buy insurance is not within the scope of Congress's taxing powers. On March 18, before passage of the bill, the Governor of Idaho, Butch Otter, was the first state governor to put a framework together to begin a legal challenge.[155] At least 36 other states were considering taking similar action at that time.[155] On March 22, Attorneys General of eleven states announced their intentions to sue the federal government, citing the bill as a violation of state sovereignty and saying Congress has no authority to require individuals to purchase health insurance.[156][157]

Less than an hour after the bill was signed into law on March 23, thirteen states – Florida as the lead, joined by Alabama, Colorado, Idaho, Louisiana, Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, Utah, and Washington – filed a lawsuit in U.S. District court in Pensacola challenging the bill.[158] Twelve of the Attorneys General involved in the suit are members of the Republican Party and one, Buddy Caldwell of Louisiana, is a Democrat who was encouraged by Republican Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal to join the suit.[159][160] Subsequently, five additional states – Arizona, Indiana, Mississippi, Nevada and North Dakota – joined in Florida's suit, bringing the number of states participating to eighteen.[161] On April 6, Minnesota Governor Tim Pawlenty said he will sue the Federal government. State Attorney General Lori Swanson had said she did not believe a lawsuit by the state was warranted, but Pawlenty could file his own brief opposing the law in his individual capacity as governor. Pawlenty said he had not yet decided whether to join an existing suit or file separately.[162]

In a press release, the Attorneys General indicated their primary basis for the challenge was a violation of state sovereignty. Their release stated, "The Constitution nowhere authorizes the United States to mandate, either directly or under threat of penalty, that all citizens and legal residents have qualifying health care coverage," and that the law puts an unfair financial burden on state governments.[158] The lawsuit states the following legal rationale:

Regulation of non-economic activity under the Commerce Clause is possible only through the Necessary and Proper Clause. The Necessary and Proper Clause confers supplemental authority only when the means adopted to accomplish an enumerated power are 'appropriate', are 'plainly adapted to that end', and are 'consistent with the letter and spirit of the constitution.' Requiring citizen-to-citizen subsidy or redistribution is contrary to the foundational assumptions of the constitutional compact.[163]

Virginia filed a separate suit based on a conflict between the Act and a recently enacted state law. Other states were either expected to join the multi-state lawsuit or are considering filing additional independent suits.[156][164][165] Members of several state legislatures are attempting to counteract and prevent elements of the bill within their states. Legislators in 29 states have introduced measures to amend their constitutions to nullify portions of the health care reform law. Thirteen state statutes have been introduced to prohibit portions of the law; two states have already enacted statutory bans. Six legislatures had attempts to enact bans, but the measures were unsuccessful.[166] In August 2010, a ballot initiative passed overwhelmingly in Missouri that would exempt the state from some provisions of the bill. Most legal analysts expect that the measure will be struck down if challenged in Federal court.[167]

Reactions from legal experts

Justice Department spokesman Charles Miller was quoted as stating, "We are confident that this statute is constitutional and we will prevail when we defend it."[168]

Michael C. Dorf, Professor of Law at Cornell University, wrote a lengthy analysis of present case law affecting the health care purchase mandate. He cited the 1922 Supreme Court case of Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. as the current precedent for invalidating Federal fines imposed via the Commerce Clause. In that case the Supreme Court ruled Congress could not impose fines through the Commerce Clause as a means to indirectly regulate activities. The case stated the Commerce Clause does not authorize Congress to "use taxation as a pretext for accomplishing a regulatory objective that it could not accomplish directly".[169] Congress does have the power through the revenue raising clauses of the constitution to make such an imposition, but in that instance the primary purpose of the tax must be to raise revenue, "a tax that serves a revenue-raising purpose is not invalid simply because it also serves a regulatory purpose."[169] He concluded that the revenue creation aspect trumped the questions raised by the Commerce Clause, and the ability to have the health care bill brought down by a legal case would require the court to find the fine's primary purpose is to influence behavior and effect regulations rather than provide revenue.[169] Case law on the Commerce Clause has changed significantly since Bailey; the precedents set in United States v. Darby Lumber Co. (1941) (explicitly overturning 1918's Hammer v. Dagenhart) and 1942's Wickard v. Filburn may have an effect on the applicability of Bailey to the PPACA.

Mark Hall, Professor of Law at Wake Forest University, specializing in health care law and policy, was quoted as saying: "Under the Due Process Clause, no Supreme Court decision since 1935 has struck down any state or federal legislation for infringing economic liberties, and any such action would be radically inconsistent with current constitutional doctrine."[170] Regarding the attempts to override the health-care bill with state laws, Hall stated, "It doesn't make sense. The federal Constitution couldn't be any clearer that federal law is supreme," and characterized the state actions as "a kind of civil disobedience, a declaration that we're not going to follow the law of the land."[171]

Several legal experts contacted by the Associated Press characterized the lawsuits as "futile":[168] the lawsuits were called "pure political posturing" by constitutional law professor Robert Sedler at Wayne State University and constitutional law professor Bruce Jacob at Stetson University disparaged the lawsuit's chances and commented that the "federal government certainly can compel people to pay taxes".[168] Constitutional law professor Jared Goldstein of Roger Williams University stated, "There was a time when these arguments would have been persuasive, and that time was 1936, when the Supreme Court declared much of the New Deal to be unconstitutional," and compared the constitutionality of the health-care bill to other social and tax legislation that was subsequently considered to be constitutional, such as Social Security or tax penalties on companies that pollute.[172] Erwin Chemerinsky, dean and constitutional law professor of the University of California, Irvine, called the bill "clearly" constitutional, explaining that "everyone at some point is going to need health care, whether if it's for an auto accident or a communicable disease, and Congress can make sure everyone pays for the system they’re likely to benefit from."[172]

Several lawyers and legal experts interviewed by the Los Angeles Times suggested that the precedent Gonzales v. Raich set in 2005 posed a particular hurdle for the lawsuits, because it interprets the Constitution as giving Congress "vast regulatory authority over interstate commerce" and is a precedent set by several members of the existing Supreme Court (including conservative Justices Scalia and Kennedy).[173] However, constitutional law professor Adam Winkler of UCLA noted that the current Supreme Court "has already shown itself to be willing to break from long-standing precedent in major cases" and "precedent rarely dictates how the court will rule" on "hot-button, partisan issues", although Winkler also disparaged the argument that Congress could not penalize people for failure to purchase health insurance.[173]

Early federal court rulings

The first federal court ruling in the legal challenges to the health care act came on August 2, 2010, in response to the suit brought by Virginia's attorney general. U.S. District Judge Henry E. Hudson denied the Justice Department's request to have the suit dismissed, citing the complex constitutional questions the law raises. In a 32-page opinion, Hudson wrote that the reform act "radically changes the landscape of health insurance coverage in America." As a result of the dismissal, a hearing will be held in Richmond on October 18 as previously scheduled.[174]

On October 8, in the first ruling supporting the law's constitutionality, a federal court rejected a private suit filed by Michigan's Thomas More Law Center and several state residents that focused on alleged violations of the Commerce Clause.[175] U.S. District Court Judge George Caram Steeh rejected the claims, ruling that Congress had the power to pass the law because it affected interstate commerce and was part of a broader regulatory scheme.[176][177] A week later, a federal judge in Florida allowed lawsuits brought by 20 states to move forward, ordering a December trial on two claims while dismissing four others. U.S. District Court Judge Roger Vinson based his ruling on the propriety of imposing Medicaid expenses on the states and the penalties tied to the individual mandate, a provision he described as "simply without prior precedent."[178][179]

Repeal proposal

HR 4972 introduced by representative Steve King (R–Iowa) provides "Effective as of the enactment of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, such Act is repealed, and the provisions of law amended or repealed by such Act are restored or revived as if such Act had not been enacted."[180]

Waivers

Interim regulations have been put in place for a specific type of employer funded insurance, the so-called "mini-med" or limited benefit plans which are low cost to employers who buy them for their employees but which cap coverage at a very low level. Such plans are sometimes offered to low paid and part-time workers, for example in fast food restaurants or purchased direct from an insurer. Most company provided health insurance from September 23, 2010 may not set an annual coverage cap lower than $750,000 [181], a lower limit which is raised in stages until 2014 by which time no insurance caps are allowed at all. By 2014 no health insurance, whether sold in the individual or group market will be allowed to place an annual cap on coverage. The waivers have been put in place to encourage employers and insurers offering mini-med plans not to withdraw medical coverage before the full regulations come into force (by which time small employers and individuals will be able to buy non-capped coverage through the exchanges) and are granted only if the employer can show that complying with the limit would mean a significant decrease in employees' benefits coverage or a significant increase in employees' premiums.[182] By early November 2010, 111 employers and insurers had been granted waivers.[183]

Among those receiving waivers were large insurers, such as Aetna and Cigna, union plans covering about one million employees and McDonald's, which has 30,000 hourly employees whose plans have annual caps of $10,500. The waivers are issued for one year and can be reapplied for.[184] [185] Referring to the adjustments as "a balancing act," Nancy-Ann DeParle, director of the Office of Health Reform at the White House, said, "The president wants to have a smooth glide path to 2014."[184] The Department of Health and Human Services website published a list of these employers which can be read here.

See also

{{{inline}}}

References

- ^ Elmendorf, Douglas W. (January 22, 2010). "Additional Information on the Effect of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act on the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund". Congressional Budget Office. Retrieved 2010-03-31.

This letter responds to questions you posed about the Congressional Budget Office's (CBO's) analysis of the effects of H.R. 3590, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA)

- ^ Pub. L. 111–148 (text) (PDF), 124 Stat. 119, to be codified as amended at scattered sections of 42 U.S.C..

- ^ a b Congressional Budget Office, Cost Estimates for H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation) March 20, 2010).

- ^ Peter Grier, Health care reform bill 101: Who will pay for reform?, Christian Science Monitor (March 21, 2010).

- ^ Grier, Peter (March 19, 2010). "Health care reform bill 101: Who must buy insurance?". Christian Science Monitor. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ "The First Presidential Debate". New York Times. September 26, 2008.

- ^ "Remarks of President Barack Obama -- Address to Joint Session of Congress". WhiteHouse.gov. February 24, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Timeline: Milestones in Obama's quest for healthcare reform". Reuters. March 22, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Kruger, Mike (October 29, 2009). "Affordable Health Care for America Act". EdLabor Journal. United States House Committee on Education and Labor. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Health Care Reform from Conception to Final Passage". Retrieved 2010-11-23.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ [1] Senate Finance Committee Hearings for the 111th Congress recorded by C-Span

- ^ Senate Finance Committee hearings for 111th Congress

- ^ "Town hall meeting on health care turns ugly". CNN. August 18, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Remarks by the President to a Joint Session of Congress on Health Care". WhiteHouse.gov. September 10, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ "Obama calls for Congress to face health care challenge". CNN. September 10, 2009. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Roll call vote 887, via Clerk.House.gov

- ^ Summary Of A 1993 Republican Health Reform Plan. Kaiser Health News. See also: Chart: Comparing Health Reform Bills: Democrats and Republicans 2009, Republicans 1993.

- ^ AG Suthers couldn’t be more wrong in his decision to file lawsuit. The Colorado Statesman.

- ^ a b Horwitz, Sari; Pershing, Ben (April 9, 2010). "Anger over health-care reform spurs rise in threats against Congress members". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 9, 2010.

- ^ "Lancaster Rep. Speaks Out Against Violence In Wake Of Healthcare Vote". Susquehanna Valley, Pennsylvania: WGAL. March 25, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Gaskell, Stephanie (March 22, 2010). "Angry over health reform vote, Conservative blogger posts Twitter call for Obama assassination". Daily News. New York. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Condon, Stephanie (March 24, 2010). "Bart Stupak Received Threatening Messages for Health Care Vote (Listen)". Political Hotsheet. CBS News. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer said today that more than 10 members of Congress have received threats in the wake of the health reform vote

- ^ a b "Michigan GOP Says Vandalism Hits Genoa Township Office". WHMI 93.5 FM. Livingston County, Michigan: The Livingston Radio Company, Inc. March 29, 2010. Retrieved April 7, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ a b "Parties trade blame over health bill threats". msnbc.com. March 24, 2010 (updated March 26, 2010). Retrieved April 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Sherman, Jake (March 24, 2010). "Coffin placed on Carnahan's lawn". The Politico. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Carter, Mike (April 6, 2010). "Yakima County man charged with threatening to kill Sen. Patty Murray". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ "Man Arrested for Pelosi Threat Has Harassment History". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 8, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ "Calif. man arrested, accused of threatening Pelosi over health care". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ Norton, Monica (March 29, 2010). "Man arrested for threatening to kill Cantor, family". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Erickson, Erick (March 29, 2010). "Does Josh Marshall Owe Eric Cantor An Apology For Inciting Violence Against Cantor's Family?". RedState. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Sherman, Jake (March 30, 2010). "Man arrested for Eric Cantor death threat". The Politico. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

- ^ Good, Chris (March 29, 2010). "Tea Party Express: On to Utah, and Another Hot Race". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "Reid Supporters Accused of Throwing Eggs at Tea Party Bus". Fox News Channel. March 29, 2010. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Reid Supporters Throw Eggs And Assault Andrew Breitbart, posted on YouTube

- ^ Christoff, Chris (March 29, 2010). "Brick smashes GOP office window in Howell". Detroit Free Press. Retrieved April 7, 2010. [dead link]

- ^ Maze, Rick (October 8, 2009). "House OKs tax breaks for military homeowners". Air Force Times. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ U.S. Const. art. I, § 7, cl. 1.

- ^ S.Amdt. 2786

- ^ "'Cornhusker' Out, More Deals In: Health Care Bill Gives Special Treatment". Fox News. March 19, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ Roll call vote 396, via Senate.gov

- ^ a b c Stolberg, Sheryl; Jeff Zeleny; Carl Hulse (March 20, 2010). "Health Vote Caps a Journey Back From the Brink". New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c Brown, Carrie; Glenn Thrush (March 20, 2010). "Pelosi steeled W.H. for health push". Politico. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ White House Unveils Revamped Reform Plan, GOP And Industry React. Kaiser Health News.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl; Robert Pear (March 3, 2010). "Obama Urges Up-or-Down Vote on Health Care Bill". New York Times. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ "Executive Order -- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act's Consistency with Longstanding Restrictions on the Use of Federal Funds for Abortion". WhiteHouse.gov. March 24, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Roll call vote 167, via Clerk.House.gov

- ^ Aro, Margaret; Mark Mooney (March 22, 2010). "Pelosi Defends Health Care Fight Tactics". ABC News. Retrieved March 23, 2010.

- ^ Stolberg, Sheryl; Robert Pear (March 23, 2010). "Obama Signs Health Care Overhaul Bill, With a Flourish". New York Times. Retrieved March 24, 2010.

- ^ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act from Wikisource.

- ^ a b "Key Points Of The Health Care Reform Bil". The Kentucky Post.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accedate=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Binckes, Jeremy (2010-03-22). "The Top 18 Immediate Effects Of The Health Care Bill". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2010-03-22.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hossain, Farhana; Tse, Archie (March 23, 2010). "Comparing the House and the Senate Health Care Proposals". New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2010..

- ^ a b "Updated Health Care Charts". Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. November 19, 2009..

- ^ a b c d e "Health Reform Implementation Timeline". Kaiser Family.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accedate=ignored (help) - ^ http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/36135106/ns/health-health_care/

- ^ Grier, Peter (2010-03-24). "Health care reform bill 101: rules for preexisting conditions". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ^ a b c Tergesen, Anne (June 5, 2010). "Insurance Relief for Early Retirees". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Kaiser: High-Risk Pool Provisions under the Health Reform Law" (PDF).

- ^ Hilzenrath, David S. (May 4, 2010). "18 states refuse to run insurance pools for those with preexisting conditions". The Washington Post.

- ^ High-Risk Insurance Pools Are Attracting Few, New York Times, November 12, 2010

- ^ "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act/Title IV/Subtitle A/Sec. 4001. National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council".

- ^ Executive Order 13544 - Establishing the National Prevention, Health Promotion, and Public Health Council, June 10, 2010, Vol. 75, No. 114, 75 FR 33983

- ^ http://www.healthcare.gov/law/about/order/byyear.html

- ^ H.R. 3590 Enrolled, section 1001 (adding section 2714 to the Public Health Service Act): "A group health plan and a health insurance issuer offering group or individual health insurance coverage that provides dependent coverage of children shall continue to make such coverage available for an adult child (who is not married) until the child turns 26 years of age."

- ^ Pear, Robert (May 10, 2010). "Rules Let Youths Stay on Parents' Insurance". New York Times.

- ^ "Young Adults and the Affordable Care Act: Protecting Young Adults and Eliminating Burdens on Families and Businesses" (PDF) (Press release). Executive Office of the President of the United States.

- ^ Note: Language in the law concerning this provision has been described as ambiguous, but representatives of the insurance industry have indicated they will comply with regulations to be issued by the Secretary of Health and Human Services reflecting this interpretation.

- Pear, Robert (March 28, 2010). "Coverage Now for Sick Children? Check Fine Print". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Holland, Steve (March 29, 2010). "Obama administration has blunt message for insurers". Reuters. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Pear, Robert (March 30, 2010). "Insurers to Comply With Rules on Children". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - Alonso-Zaldivar, Ricardo (March 24, 2010). "Gap in Health Care Law's Protection for Children". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- Pear, Robert (March 28, 2010). "Coverage Now for Sick Children? Check Fine Print". The New York Times. Retrieved April 8, 2010.

- ^ U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (June 28, 2010). "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; Requirements for Group Health Plans and Health Insurance Issuers Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act Relating to Preexisting Condition Exclusions, Lifetime and Annual Limits, Rescissions, and Patient Protections; Final Rule and Proposed Rule". Federal Register. 75 (123): 37187–37241. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- ^ Bowman, Lee (2010-03-22). "Health reform bill will cause several near-term changes". Scripps Howard News Service. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Rao, Smriti (2010-03-22). "Health-Care Reform Passed. So What Does It Mean?". 80beats. Discover. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ H.R. 3590 public print, sec. 10101(f), adding Sec. 2718. Bringing down the cost of health care coverage of the Public Health Service Act.

- ^ Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, http://healthreformgps.org/resources/center-for-medicare-and-medicaid-innovation/.

- ^ "IRS Issues Guidance Explaining 2011 Changes to Flexible Spending Arrangements". www.irs.gov. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ Smith, Donna (March 19, 2010). "FACTBOX-US healthcare bill would provide immediate benefits". Reuters.

- ^ http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-drop/n-2010-69.pdf

- ^ "Costly changes to 1099 reporting in health care law".

- ^ a b "Instructions for Form 1099-MISC" (PDF).

- ^ a b "U.S. Government Printing Office".

- ^ "Healthcare Law Includes Tax Credit, Form 1099 Requirement".

- ^ "Health Care Bill Brings Major 1099 Changes".

- ^ http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr3590pp/pdf/BILLS-111hr3590pp.pdf pp 2000. 2001, 2002, 2003

- ^ Alonso-Zaldivar, Ricardo (March 24, 2010). "Gap in Health Care Law's Protection for Children". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ a b c Galewitz, Phil (March 26, 2010). "Consumers Guide To Health Reform". Kaiser Health News.

- ^ a b "5 key things to remember about health care reform". CNN. March 25, 2010. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ Kristen McNamara, What Health Overhaul Means for Small Businesses, Wall Street Journal (25 March 2010).

- ^ a b c d Downey , Jamie (March 24, 2010). "Tax implications of health care reform legislation". Boston Globe. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Carney: Health insurance law will benefit senior citizens, The Daily Item, Sunbury PA (March 26, 2010).

- ^ Section 10108 FREE CHOICE VOUCHERS

- ^ "Health Reform, Point by Point - Bills Compared". Wall Street Journal. March 22, 2010. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ Burkes, Paula (November 8, 2009). "Medical Expense Accounts Could be Limited to $2,500". The Oklahoman..

- ^ Spencer, Jean (2010-03-22). "Menu Measure: Health Bill Requires Calorie Disclosure". Washington Wire. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ Galewitz, Phil (2010-03-22). "Health reform and you: A new guide". Kaiser Health News. MSNBC. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- ^ "Health Care Reform Bill 101". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ "Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act/Title I/Subtitle E/Part I/Subpart A".

- ^ Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act: Title I: Subtitle E: Part I: Subpart A: Premium Calculation

- ^ "Refundable Tax Credit".

- ^ a b "An Analysis of Health Insurance Premiums Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Policies to Improve Affordability and Accountability". The White House.

- ^ "Kaiser Family Foundation:Health Reform Subsidy Calculator -- Premium Assistance for Coverage in Exchanges/Gateways".

- ^ H.R. 3590 Public Print, section 1312: "... the only health plans that the Federal Government may make available to Members of Congress and congressional staff with respect to their service as a Member of Congress or congressional staff shall be health plans that are (I) created under this Act (or an amendment made by this Act); or (II) offered through an Exchange established under this Act (or an amendment made by this Act)."

- ^ "Health Care reform Reconciliation Act" (PDF).

- ^ Krantz, Matt (March 24, 2010). "Highlights of the Tax Provisions in Health Care Reform". Accuracy in Media. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Wyden: Health Care Lawsuits Moot, States Can Opt Out Of Mandate". HuffingtonPost.com. March 24, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ H.R. 3590 Public Print, section 1332.

- ^ Gold, Jenny (2010-01-15). "'Cadillac' Insurance Plans Explained". Kaiser Health News.

- ^ "H.R. 4872, THE HEALTH CARE & EDUCATION AFFORDABILITY RECONCILIATION ACT of 2010 IMPLEMENTATION TIMELINE" (PDF). US House COMMITTEES ON WAYS & MEANS, ENERGY & COMMERCE, AND EDUCATION & LABOR. March 18, 2010. p. 7. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ^ a b c "Correction Regarding the Longer-Term Effects of the Manager's Amendment to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. December 19, 2009. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ CNN (March 18, 2010). "Where does health care reform stand?". Retrieved May 12, 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author=has generic name (help). - ^ "H.R. 3590, Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. March 11, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010..

- ^ a b "H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. March 18, 2010. Retrieved March 22, 2010..

- ^ http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11376/RyanLtrhr4872.pdf

- ^ http://hotair.com/archives/2010/03/19/cbo-confirms-obamacare-with-doctor-fix-will-actually-add-billions-to-the-deficit/

- ^ http://www.nationalreview.com/critical-condition/55996/obamacare-s-cooked-books-and-doc-fix/james-c-capretta

- ^ http://www.investors.com/NewsAndAnalysis/Article/554579/201011221909/GOP-Might-Target-ObamaCare-As-Part-Of-A-Medicare-Doc-Fix.aspx

- ^ Dennis, Steven (March 18, 2010). "CBO: Health Care Overhaul Would Cost $940 Billion". Roll Call. Economist Group. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

- ^ Klein, Ezra (March 22, 2010). "What does the health-care bill do in its first year?". Washington Post.

- ^ Farley, Robert (March 18, 2010). "Pelosi: CBO says health reform bill would cut deficits by $1.2 trillion in second decade". PolitiFact. St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ Uwe Reinhardt (24 March 2010). "Wrapping Your Head Around the Health Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Holtz-Eakin, Douglas (March 21, 2010). "The Real Arithmetic of Health Care Reform". The New York Times.

- ^ James, Frank (March 19, 2010). "Health Overhaul Another Promise U.S. Can't Afford: Expert". The Two-Way. National Public Radio. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ "Congress Has Good Record of Implementing Medicare Savings". CBPP. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ "Can Congress cut Medicare costs?". voices.washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2010-03-28.

- ^ a b "Cost Estimate for Pending Health Care Legislation" (PDF). Congressional Budget Office. March 20, 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-28. [dead link]

- ^ a b c Trumbull, Mark (March 23, 2010). "Obama signs health care bill: Who won't be covered?". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ http://www.politico.com/static/PPM110_091211_financial_impact.html

- ^ http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/113xx/doc11376/RyanLtrhr4872.pdf

- ^ http://hotair.com/archives/2010/03/19/cbo-confirms-obamacare-with-doctor-fix-will-actually-add-billions-to-the-deficit/

- ^ http://www.nationalreview.com/critical-condition/55996/obamacare-s-cooked-books-and-doc-fix/james-c-capretta

- ^ http://www.investors.com/NewsAndAnalysis/Article/554579/201011221909/GOP-Might-Target-ObamaCare-As-Part-Of-A-Medicare-Doc-Fix.aspx

- ^ a b CBO.(Nov 2009).[www.cbo.gov/doc.cfm?index=10781&type=1 An Analysis of Health Insurance Premiums Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act].

- ^ Gawande, Atul (2009). "Testing, Testing". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 22, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Farley, Robert (March 19, 2010). "Obama says health reform legislation could reduce costs in employer plans by up to $3,000". PolitiFact. St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ^ "Report Says Health Care Will Cover More, Cost More: Mixed Review For New Health Care Law Says Covering More Still Comes With Greater Costs," Associated Press, April 23, 2010

- ^ Richard S. Foster, Estimated Financial Effects of the “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act” as Amended, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, April 22, 2010

- ^ Leonhardt, David (2010). "In Health Bill, Obama Attacks Wealth Inequality". The New York Times. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Gienger, Viola (March 27, 2010). "AT&T, Deere CEOs Called by Waxman to Back Up Health-Bill Costs". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. Retrieved April 7, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Locke G. Don't Believe the Writedown Hype. Wall Street Journal

- ^ Brown, Robbie (April 24, 2010). "States Warn of 'Obamacare' Scams". The New York Times. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 23, 2010). "'Obamacare' is a victory I welcome". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Blendon RJ, Benson JM (2010). "Public opinion at the time of the vote on health care reform". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (16): e55. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1003844. PMID 20375397.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Barbieri, Rich (March 22, 2010). "CNN poll: Americans don't like health care bill". CNN. Retrieved 2010-03-27.

- ^ Page, Susan (March 24, 2010). "Poll: Health care plan gains favor". USA Today. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- ^ "The President and Health Care Reform: Before and After the House Vote" (PDF). CBS News. March 23, 2010. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- ^ "CNN Opinion Research, March 25–28" (PDF).

- ^ Jones, Jeffrey M. (March 25, 2010). "Obama Job Approval at 51% After Healthcare Vote". Gallup. Princeton, NJ. Retrieved 2010-04-07.