Psychiatry: Difference between revisions

Psychiatrick (talk | contribs) added page number |

Psychiatrick (talk | contribs) correction |

||

| Line 76: | Line 76: | ||

Doctor Petros Arguriou said, “Psychiatric definitions are voraciously expanding and if this tendency is left unchecked and uncontrolled it could engulf pretty much of us.”<ref name=Arguriou/> |

Doctor Petros Arguriou said, “Psychiatric definitions are voraciously expanding and if this tendency is left unchecked and uncontrolled it could engulf pretty much of us.”<ref name=Arguriou/> |

||

====Skepticism |

====Skepticism about the concept of mental disorders==== |

||

There are quite persuasive reasons to doubt the ontic status of mental disorders.<ref name=Phillips>{{cite journal|last=Phillips|first=James et al.|title=The Six Most Essential Questions in Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Pluralogue. Part 1: Conceptual and Definitional Issues in Psychiatric Diagnosis.|journal=[[Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine]]|year=2012|month=January 13|volume=7|issue=3|pages=1–51|doi=10.1186/1747-5341-7-3|pmid=22243994|url=http://www.peh-med.com/content/pdf/1747-5341-7-3.pdf|accessdate=24 January 2012|publisher=BioMed Central|issn=1747-5341}}</ref>{{rp|13}} Mental disorders engender ontological skepticism on three levels: |

There are quite persuasive reasons to doubt the ontic status of mental disorders.<ref name=Phillips>{{cite journal|last=Phillips|first=James et al.|title=The Six Most Essential Questions in Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Pluralogue. Part 1: Conceptual and Definitional Issues in Psychiatric Diagnosis.|journal=[[Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine]]|year=2012|month=January 13|volume=7|issue=3|pages=1–51|doi=10.1186/1747-5341-7-3|pmid=22243994|url=http://www.peh-med.com/content/pdf/1747-5341-7-3.pdf|accessdate=24 January 2012|publisher=BioMed Central|issn=1747-5341}}</ref>{{rp|13}} Mental disorders engender ontological skepticism on three levels: |

||

# Mental disorders are abstract entities that cannot be directly appreciated with the human senses or indirectly, as one might with macro- or microscopic objects. |

# Mental disorders are abstract entities that cannot be directly appreciated with the human senses or indirectly, as one might with macro- or microscopic objects. |

||

Revision as of 01:10, 27 January 2012

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the study and treatment of mental disorders. These mental disorders include various affective, behavioural, cognitive and perceptual abnormalities. The term was first coined by the German physician Johann Christian Reil in 1808, and literally means the 'medical treatment of the mind' (psych-: mind; from Ancient Greek psykhē: soul; -iatry: medical treatment; from Gk. iātrikos: medical, iāsthai: to heal). A medical doctor specializing in psychiatry is a psychiatrist.

Psychiatric assessment typically starts with a mental status examination and the compilation of a case history. Psychological tests and physical examinations may be conducted, including on occasion the use of neuroimaging or other neurophysiological techniques. Mental disorders are diagnosed in accordance with criteria listed in diagnostic manuals such as the widely used Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), published by the American Psychiatric Association, and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), edited and used by the World Health Organization. The fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5) is scheduled to be published in 2013, and its development is suspected to be of significant interest to many medical fields.[3]

Psychiatric treatment applies a variety of modalities, including psychoactive medication, psychotherapy and a wide range of other techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation. Treatment may be delivered on an inpatient or outpatient basis, depending on the severity of functional impairment or on other aspects of the disorder in question. Research and treatment within psychiatry as a whole are conducted on an interdisciplinary basis, sourcing an array of sub-specialties and theoretical approaches.

History

Ancient

Although one may trace its germination to the late eighteenth century, the beginning of psychiatry as a medical specialty is dated to the middle of the nineteenth century.[4]Starting in the 5th century BCE, mental disorders, especially those with psychotic traits, were considered supernatural in origin.[5] This view existed throughout ancient Greece and Rome.[5] Early manuals about mental disorders were created by the Greeks.[4] In the 4th century BCE, Hippocrates theorized that physiological abnormalities may be the root of mental disorders.[5][5] Religious leaders often turned to versions of exorcism to treat mental disorders often utilizing cruel and barbarous methods.[5]

Middle Ages

Specialist hospitals were built in Baghdad in 705 AD, followed by Fes in the early 8th century, and Cairo in 800 AD.[citation needed]

Physicians who wrote on mental disorders and their treatment in the Medieval Islamic period included Muhammad ibn Zakarīya Rāzi (Rhazes), the Arab physician Najab ud-din Muhammad[citation needed], and Abu Ali al-Hussain ibn Abdallah ibn Sina, known in the West as Avicenna.[6]

Specialist hospitals were built in medieval Europe from the 13th century to treat mental disorders but were utilized only as custodial institutions and did not provide any type of treatment.[7] Founded in the 13th century, Bethlem Royal Hospital in London is one of the oldest lunatic asylums.[7] By 1547 the City of London acquired the hospital and continued its function until 1948.[8] It is now part of the National Health Service and is an NHS Foundation Trust.

Early modern period

In 1656, Louis XIV of France created a public system of hospitals for those suffering from mental disorders, but as in England, no real treatment was applied.[8] In 1713 the Bethel Hospital Norwich was opened, the first purpose built asylum in England, founded by Mary Chapman [1] . In 1758 English physician William Battie wrote his Treatise on Madness which called for treatments to be utilized in asylums.[9] Thirty years later, then ruling monarch in England George III was known to be suffering from a mental disorder.[5] Following the King's remission in 1789, mental illness was seen as something which could be treated and cured.[5] French medic Philippe Pinel introduced humane treatment approaches to those suffering from mental disorders.[5] In 1793, in Parice psychiatric hospital “Bisetr”, Pinel released mental patients of chains beginning what has been called the bright epoch of psychiatry.[10] William Tuke adopted the methods outlined by Pinel and that same year Tuke opened the York Retreat in England.[5] Tuke's Retreat became a model throughout the world for humane and moral treatment of patients suffering from mental disorders.[11] The York Retreat inspired similar institutions in the United States, most notably the Brattleboro Retreat and the Hartford Retreat (now the Institute of Living).

19th century

At the turn of the century, England and France combined had only a few hundred individuals in asylums.[12] By the late 1890s and early 1900s, this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands.[12] The United States housed 150,000 patients in mental hospitals by 1904.[12] German speaking countries housed more than 400 public and private sector asylums.[12] These asylums were critical to the evolution of psychiatry as they provided places of practice throughout the world.[12]

On the continent, universities often played a part in the administration of the asylums[13] and, because of the relationship between the universities and asylums, scores of psychiatrists were being educated in Germany.[13]. However, because of Germany's individual states and the lack of national regulation of asylums, the country had no organized centralization of asylums or psychiatry.[12] The United Kingdom, unlike Germany, possessed a national body for asylum superintendents - the Medico-Psychological Association - established in 1866 under the Presidency of William A.F. Browne.[14]

In the United States in 1834 Anna Marsh, a physician's widow, deeded the funds to build her country's first financially-stable private asylum. The Brattleboro Retreat marked the beginning of America's private psychiatric hospitals challenging state institutions for patients, funding, and influence. Although based on England's York Retreat, it would be followed by specialty institutions of every treatment philosophy.

In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. This was the year in which William A.F. Browne achieved his appointment as Superintendent of the Crichton Royal at Dumfries in southern Scotland.

However, the new idea that mental illness could be ameliorated during the mid-nineteenth century were disappointed.[15] Psychiatrists were pressured by an ever increasing patient population.[15] The average number of patients in asylums in the United States jumped 927%.[15] Numbers were similar in England and Germany.[15] Overcrowding was rampant in France where asylums would commonly take in double their maximum capacity.[16] Increases in asylum populations may have been a result of the transfer of care from families and poorhouses, but the specific reasons as to why the increase occurred is still debated today.[17][18] No matter the cause, the pressure on asylums from the increase was taking its toll on the asylums and psychiatry as a specialty. Asylums were once again turning into custodial institutions[19] and the reputation of psychiatry in the medical world had hit an extreme low.[20]

20th century

Disease classification and rebirth of biological psychiatry

The 20th century introduced a new psychiatry into the world. Different perspectives of looking at mental disorders began to be introduced. The career of Emil Kraepelin reflects the convergence of different disciplines in psychiatry.[21] Kraepelin initially was very attracted to psychology and ignored the ideas of anatomical psychiatry.[21] Following his appointment to a professorship of psychiatry and his work in a university psychiatric clinic, Kraepelin's interest in pure psychology began to fade and he introduced a plan for a more comprehensive psychiatry.[22][23] Kraepelin began to study and promote the ideas of disease classification for mental disorders, an idea introduced by Karl Ludwig Kahlbaum.[23] The initial ideas behind biological psychiatry, stating that the different mental disorders were all biological in nature, evolved into a new concept of "nerves" and psychiatry became a rough approximation of neurology and neuropsychiatry.[24] However, Kraepelin was criticized for considering schizophrenia as a biological illness in the absence of any detectable histologic or anatomic abnormalities.[25]: 221 While Kraepelin tried to find organic causes of mental illness, he adopted many theses of positivist medicine, but understanding is not based on etiology because the causes of madness cannot be determined with any precision.[26]

Following Sigmund Freud's death, ideas stemming from psychoanalytic theory also began to take root.[27] The psychoanalytic theory became popular among psychiatrists because it allowed the patients to be treated in private practices instead of warehoused in asylums.[27] By the 1970s the psychoanalytic school of thought had become marginalized within the field.[27]

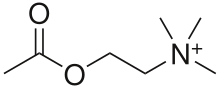

Biological psychiatry reemerged during this time. Psychopharmacology became an integral part of psychiatry starting with Otto Loewi's discovery of the neuromodulatory properties of acetylcholine; thus identifying it as the first-known neurotransmitter.[28] Neuroimaging was first utilized as a tool for psychiatry in the 1980s.[29] The discovery of chlorpromazine's effectiveness in treating schizophrenia in 1952 revolutionized treatment of the disease,[30] as did lithium carbonate's ability to stabilize mood highs and lows in bipolar disorder in 1948.[31] Psychotherapy was still utilized, but as a treatment for psychosocial issues.[32] Genetics were once again thought to play a role in mental illness.[28] Molecular biology opened the door for specific genes contributing to mental disorders to be identified.[28]

Anti-psychiatry and deinstitutionalization

The introduction of psychiatric medications and the use of laboratory tests altered the doctor-patient relationship between psychiatrists and their patients.[33] Psychiatry's shift to the hard sciences had been interpreted as a lack of concern for patients.[33] Anti-psychiatry had become more prevalent in the late twentieth century due to this and publications in the media which conceptualized mental disorders as myths.[34] Others in the movement argued that psychiatry was a form of social control and demanded that institutionalized psychiatric care, stemming from Pinel's thereapeutic asylum, be abolished.[35]

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was one treatment that the anti-psychiatry movement wanted eliminated.[36] They alleged that ECT damaged the brain and was used as a tool for discipline.[36] While some believe there is no evidence that ECT damages the brain,[37][38][39] there are some citations that ECT does cause damage.[40][41] Sometimes ECT is used as punishment or as a threat and there have been isolated incidents where the use of ECT was threatened to keep the patients "in line".[36] The prevalence of psychiatric medication helped initiate deinstitutionalization,[42] the process of discharging patients from psychiatric hospitals to the community.[43] The pressure from the anti-psychiatry movements and the ideology of community treatment from the medical arena helped sustain deinstitutionalization.[42] Thirty-three years after deinstitutionalization started in the United States, only 19% of the patients in state hospitals remained.[42] Mental health professionals envisioned a process wherein patients would be discharged into communities where they could participate in a normal life while living in a therapeutic atmosphere.[42] Psychiatrists were criticized, however, for failing to develop community-based support and treatment. Community-based facilities were not available because of the political infighting between in-patient and community-based social services, and an unwillingness by social services to dispense funding to provide adequately for patients to be discharged into community-based facilities.

Political abuse of psychiatry

Psychiatrists around the world have been involved in the suppression of individual rights by states wherein the definitions of mental disease had been expanded to include political disobedience.[44]: 6 Nowadays, in many countries, political prisoners are sometimes confined to mental institutions and abused therein.[45]: 3 Psychiatry possesses a built-in capacity for abuse which is greater than in other areas of medicine.[46]: 65 The diagnosis of mental disease can serve as proxy for the designation of social dissidents, allowing the state to hold persons against their will and to insist upon therapies that work in favour of ideological conformity and in the broader interests of society.[46]: 65 In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials.[46]: 65 In Nazi Germany in the 1940s, the 'duty to care' was violated on an enormous scale: A reported 300,000 individuals were sterilized and 100,000 killed in Germany alone, as were many thousands further afield, mainly in eastern Europe.[47] From the 1960s up to 1986, political abuse of psychiatry was reported to be systematic in the Soviet Union, and to surface on occasion in other Eastern European countries such as Romania, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Yugoslavia.[46]: 66 A "mental health genocide" reminiscent of the Nazi aberrations has been located in the history of South African oppression during the apartheid era.[48] A continued misappropriation of the discipline was subsequently attributed to the People's Republic of China.[49]

K. Fulford, A. Smirnov, and E. Snow state: “An important vulnerability factor, therefore, for the abuse of psychiatry, is the subjective nature of the observations on which psychiatric diagnosis currently depends.”[50] According to American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, these authors, who correctly emphasize the value-laden nature of psychiatric diagnoses and the subjective character of psychiatric classifications, fail to accept the role of psychiatric power.[51] Musicologists, drama critics, art historians, and many other scholars also create thier own subjective classifications; however, lacking state-legitimated power over persons, their classifications do not lead to anyone’s being deprived of property, liberty, or life.[51] For instance, plastic surgeon’s classification of beauty is subjective, but the plastic surgeon cannot treat his or her patient without the patient’s consent, therefore, there cannot be any political abuse of plastic surgery.[51] The bedrock of political medicine is coercion masquerading as medical treatment.[52]: 497 What transforms coercion into therapy are physicians diagnosing the person’s condition a “illness,” declaring the intervention they impose on the victim a “treatment,” and legislators and judges legitimating these categorizations as “illnesses” and “treatments.”[52]: 497 In the same way, physician-eugenicists advocated killing certain disabled or ill persons as a form of treatment for both society and patient long before the Nazis came to power.[52]: 497

From the commencement of his political career, Hitler put his struggle against “enemies of the state” in medical rhetoric.[52]: 502 In 1934, addressing the Reichstag, Hitler declared, “I gave the order… to burn out down to the raw flesh the ulcers of our internal well-poisoning.”[53]: 494 [52]: 502 The entire German nation and its National Socialist politicians learned to think and speak in such terms.[52]: 502 Werner Best, Reinhard Heydrich’s deputy, stated that the task of the police was “to root out all symptoms of disease and germs of destruction that threatened the political health of the nation… [In addition to Jews,] most [of the germs] were weak, unpopular and marginalized groups, such as gypsies, homosexuals, beggars, ‘antisocials,’ ‘work-shy,’ and ‘habitual criminals.’”[53]: 541 [52]: 502

In spite of all the evidence, people underappreciate or, more often, ignore the political implications of the therapeutic character of Nazism and of the use of medical metaphors in modern democracies.[52]: 503 Dismissed as an “abuse of psychiatry,” this practice is touchy subject not because the story makes psychiatrists in Nazi Germany look bad, but because it highlights the dramatic similarities between pharmacratic controls in Germany under Nazism and those in the USA under what is euphemistically called the “free market.”[52]: 503

Medicalization of deviance

The concept of medicalization is created by sociologists and used for explaining how medical knowledge is applied to a series of behaviors, over which medicine exerts control, although those behaviors are not self-evidently medical or biological.[54] According to Kittrie, a number of phenomena considered "deviant", such as alcoholism, drug addiction and mental illness, were originally considered as moral, then legal, and now medical problems.[55]: 1 [56] As a result of these perceptions, peculiar deviants were subjected to moral, then legal, and now medical modes of social control.[55]: 1 Similarly, Conrad and Schneider concluded their review of the medicalization of deviance by supposing that three major paradigms may be identified that have reigned over deviance designations in different historical periods: deviance as sin; deviance as crime; and deviance as sickness.[55]: 1 [57]: 36 According to Italian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia and his followers, whose approach pointed out the role of psychiatric institutions in the control and medicalization of deviant behaviors and social problems, psychiatry is used as the provider of scientific support for social control to the existing establishment, and the ensuing standards of deviance and normality brought about repressive views of discrete social groups.[58]: 70 As scholars have long argued, governmental and medical institutions code menaces to authority as mental diseases during political disturbances.[59]: 14 According to Mike Fitzpatrick, resistance to medicalization was a common theme of the gay liberation, anti-psychiatry, and feminist movements of the 1970s, but now there is actually no resistance to the advance of government intrusion in lifestyle if it is thought to be justified in terms of public health.[60] Moreover, the pressure for medicalization also comes from society itself.[60] Feminists, who once opposed state intervention as oppressive and patriarchal, now demand more coercive and intrusive measures to deal with child abuse and domestic violence.[60] When faced with demands for measures to curtail smoking in public, binge-drinking, gambling or obesity, ministers say that “we must guard against charges of nanny statism.”[60] The “nanny state” has turned into the “therapeutic state” where nanny has given way to counselor.[60] Nanny just told people what to do; counselors also tell them what to think and what to feel.[60] The “nanny state” was punitive, austere, and authoritarian, the therapeutic state is touchy-feely, supportive — and even more authoritarian.[60] According to American psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, “the therapeutic state swallows up everything human on the seemingly rational ground that nothing falls outside the province of health and medicine, just as the theological state had swallowed up everything human on the perfectly rational ground that nothing falls outside the province of God and religion.”[52]: 515 Faced with the problem of “madness,” Western individualism proved to be ill prepared to defend the rights of the individual: modern man has no more right to be a madman than medieval man had a right to be a heretic because if once people agree that they have identified the one true God, or Good, it brings about that they have to guard members and nonmembers of the group from the temptation to worship false gods or goods.[52]: 496 A secularization of God and the medicalization of good resulted in the post-Enlightenment version of this view: once people agree that they have identified the one true reason, it brings about that they have to guard against the temptation to worship unreason — that is, madness.[52]: 496

As American psychiatrist Loren Mosher pointed out, psychiatry and the DSM today have become “a matter of fashion, politics and, like the pharmaceutical house connection, money.”[61]

Doctor Petros Arguriou said, “Psychiatric definitions are voraciously expanding and if this tendency is left unchecked and uncontrolled it could engulf pretty much of us.”[61]

Skepticism about the concept of mental disorders

There are quite persuasive reasons to doubt the ontic status of mental disorders.[62]: 13 Mental disorders engender ontological skepticism on three levels:

- Mental disorders are abstract entities that cannot be directly appreciated with the human senses or indirectly, as one might with macro- or microscopic objects.

- Mental disorders are not clearly natural processes whose detection is untarnished by the imposition of values, or human interpretation.

- It is unclear whether they should be conceived as abstractions that exist in the world apart from the individual persons who experience them, and thus instantiate them.[62]: 13

Transinstitutionalization and the aftermath

In 1963, US president John F. Kennedy introduced legislation delegating the National Institute of Mental Health to administer Community Mental Health Centers for those being discharged from state psychiatric hospitals.[42] Later, though, the Community Mental Health Center's focus was diverted to provide psychotherapy sessions for those suffering from acute but mild mental disorders.[42] Ultimately there were no arrangements made for actively and severely mentally ill patients who were being discharged from hospitals.[42] Some of those suffering from mental disorders drifted into homelessness or ended up in prisons and jails.[42][63] Studies found that 33% of the homeless population and 14% of inmates in prisons and jails were already diagnosed with a mental illness.[42][64]

Psychiatry, like most medical specialties has a continuing, significant need for research into its diseases, classifications and treatments.[65] Psychiatry adopts biology's fundamental belief that disease and health are different elements of an individual's adaptation to an environment.[66] But psychiatry also recognizes that the environment of the human species is complex and includes physical, cultural, and interpersonal elements.[66] In addition to external factors, the human brain must contain and organize an individual's hopes, fears, desires, fantasies and feelings.[66] Psychiatry's difficult task is to bridge the understanding of these factors so that they can be studied both clinically and physiologically.[66]

Theory and focus

"Psychiatry, more than any other branch of medicine, forces its practitioners to wrestle with the nature of evidence, the validity of introspection, problems in communication, and other long-standing philosophical issues" (Guze, 1992, p.4).

The term psychiatry (Greek "ψυχιατρική", psychiatrikē), coined by Johann Christian Reil in 1808, comes from the Greek "ψυχή" (psychē: "soul or mind") and "ιατρός" (iatros: "healer").[67][68][69] It refers to a field of medicine focused specifically on the mind, aiming to study, prevent, and treat mental disorders in humans.[70][71][72] It has been described as an intermediary between the world from a social context and the world from the perspective of those who are mentally ill.[73]

Those who practice psychiatry are different than most other mental health professionals and physicians in that they must be familiar with both the social and biological sciences.[71] The discipline is interested in the operations of different organs and body systems as classified by the patient's subjective experiences and the objective physiology of the patient.[74] Psychiatry exists to treat mental disorders which are conventionally divided into three very general categories: mental illness, severe learning disability, and personality disorder.[75] While the focus of psychiatry has changed little throughout time, the diagnostic and treatment processes have evolved dramatically and continue to do so. Since the late 20th century, the field of psychiatry has continued to become more biological and less conceptually isolated from the field of medicine.[76]

Scope of practice

While the medical specialty of psychiatry utilizes research in the field of neuroscience, psychology, medicine, biology, biochemistry, and pharmacology,[77] it has generally been considered a middle ground between neurology and psychology.[78] Unlike other physicians and neurologists, psychiatrists specialize in the doctor-patient relationship and are trained to varying extents in the use of psychotherapy and other therapeutic communication techniques.[78] Psychiatrists also differ from psychologists in that they are physicians and the entirety of their post-graduate training is revolved around the field of medicine.[79] Psychiatrists can therefore counsel patients, prescribe medication, order laboratory tests, order neuroimaging, and conduct physical examinations.[80]

Ethics

Like other purveyors of professional ethics, the World Psychiatric Association issues an ethical code to govern the conduct of psychiatrists. The psychiatric code of ethics, first set forth through the Declaration of Hawaii in 1977, has been expanded through a 1983 Vienna update and, in 1996, the broader Madrid Declaration. The code was further revised in Hamburg, 1999. The World Psychiatric Association code covers such matters as patient assessment, up-to-date knowledge, the human dignity of incapacitated patients, confidentiality, research ethics, sex selection, euthanasia,[81] organ transplantation, torture,[82][83] the death penalty, media relations, genetics, and ethnic or cultural discrimination.[84] In establishing such ethical codes, the profession has responded to a number of controversies about the practice of psychiatry.

Subspecialties

Various subspecialties and/or theoretical approaches exist which are related to the field of psychiatry. They include the following:

- Addiction psychiatry; focuses on evaluation and treatment of individuals with alcohol, drug, or other substance-related disorders, and of individuals with dual diagnosis of substance-related and other psychiatric disorders.

- Biological psychiatry; an approach to psychiatry that aims to understand mental disorders in terms of the biological function of the nervous system.

- Child and adolescent psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specialises in work with children, teenagers, and their families.

- Community psychiatry; an approach that reflects an inclusive public health perspective and is practiced in community mental health services.[85]

- Cross-cultural psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry concerned with the cultural and ethnic context of mental disorder and psychiatric services.

- Emergency psychiatry; the clinical application of psychiatry in emergency settings.

- Forensic psychiatry; the interface between law and psychiatry.

- Geriatric psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry dealing with the study, prevention, and treatment of mental disorders in humans with old age.

- Liaison psychiatry; the branch of psychiatry that specializes in the interface between other medical specialties and psychiatry.

- Military psychiatry; covers special aspects of psychiatry and mental disorders within the military context.

- Neuropsychiatry; branch of medicine dealing with mental disorders attributable to diseases of the nervous system.

- Social psychiatry; a branch of psychiatry that focuses on the interpersonal and cultural context of mental disorder and mental wellbeing.

In the United States, psychiatry is one of the specialties which qualify for further education and board-certification in pain medicine, palliative medicine, and sleep medicine.

Approaches

Psychiatric illnesses can be conceptualised in a number of different ways. The biomedical approach examines signs and symptoms and compares them with diagnostic criteria. Mental illness can be assessed, conversely, through a narrative which tries to incorporate symptoms into a meaningful life history and to frame them as responses to external conditions. Both approaches are important in the field of psychiatry,[86] but have not sufficiently reconciled to settle controversy over either the selection of a psychiatric paradigm or the specification of psychopathology. The notion of a "biopsychosocial model" is often used to underline the multifactorial nature of clinical impairment.[87][88][89] Alternatively, a "biocognitive model" acknowledges the physiological basis for the mind's existence, but identifies cognition as an irreducible and independent realm in which disorder may occur.[87][88][89] The biocognitive approach includes a mentalist etiology and provides a dualist revision of the biopsychosocial view, reflecting the efforts of psychiatrist Niall McLaren to bring the discipline into scientific maturity in accordance with the paradigmatic standards of philosopher Thomas Kuhn.[87][88][89]

Industry and academia

Practitioners

All physicians can diagnose mental disorders and prescribe treatments utilizing principles of psychiatry. Psychiatrists are either: 1) clinicians who specialize in psychiatry and are certified in treating mental illness;[90] or (2) scientists in the academic field of psychiatry who are qualified as research doctors in this field. Psychiatrists may also go through significant training to conduct psychotherapy, psychoanalysis and cognitive behavioral therapy, but it is their training as physicians that differentiates them from other mental health professionals.[90]

Research

Psychiatric research is, by its very nature, interdisciplinary. It combines social, biological and psychological perspectives to understand the nature and treatment of mental disorders.[92] Clinical and research psychiatrists study basic and clinical psychiatric topics at research institutions and publish articles in journals.[77][93][94][95] Under the supervision of institutional review boards, psychiatric clinical researchers look at topics such as neuroimaging, genetics, and psychopharmacology in order to enhance diagnostic validity and reliability, to discover new treatment methods, and to classify new mental disorders.[96]

Clinical application

Diagnostic systems

See also Diagnostic classification and rating scales used in psychiatry

Mental disorders were first included in the sixth revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-6) in 1949.[97] Three years later, the American Psychiatric Association created its own classification system, DSM-I.[97] The definitions of most psychiatric diagnoses consist of combinations of phenomenological criteria, such as symptoms and signs and their course over time.[97] Expert committees combined them in variable ways into categories of mental disorders, defined and redefined them again and again over the last half century.[97] The majority of these diagnostic categories are called “disorders” and are not validated by biological criteria, as most medical diseases are; although they pretend to represent medical diseases and look like medical diagnoses.[97] These diagnostic categories are actually embedded in top-down classifications, similar to the early botanic classifications of plants in the 17th and 18th centuries, when experts decided a priori about which classification criterion to use, for instance, whether the shape of leaves or fruiting bodies were the main criterion for classifying plants.[97] Since the era of Kraepelin, psychiatrists have been trying to differentiate mental disorders by using clinical interviews.[98]

In 1972, psychologist David Rosenhan published the Rosenhan experiment, a study questioning the validity of psychiatric diagnoses.[99] The study arranged for eight individuals with no history of psychopathology to attempt admission into psychiatric hospitals. The individuals included a graduate student, psychologists, an artist, a housewife, and two physicians, including one psychiatrist. All eight individuals were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Psychiatrists then attempted to treat the individuals using psychiatric medication. All eight were discharged within 7 to 52 days. In a later part of the study, psychiatric staff were warned that pseudo-patients might be sent to their institutions, but none were actually sent. Nevertheless, a total of 83 patients out of 193 were believed by at least one staff member to be actors. The study concluded that individuals without mental disorders were indistinguishable from those suffering from mental disorders.[99] Critics such as Robert Spitzer placed doubt on the validity and credibility of the study, but did concede that the consistency of psychiatric diagnoses needed improvement.[100] It is now realized that the psychiatric diagnostic criteria are not perfect. In the last century, there was little progress in psychiatric diagnosis, and, therefore, refinement of DSM can make only modest improvement, if any.[98] To further refine psychiatric diagnosis, according to Tadafumi Kato, the only way is to create a new classification of diseases based on the neurobiological features of each mental disorder.[98] On the other hand, according to Heinz Katsching, neurologists are advising psychiatrists just to replace the term “mental illness” by “brain illness.”[97]

Psychiatric diagnoses take place in a wide variety of settings and are performed by many different health professionals. Therefore, the diagnostic procedure may vary greatly based upon these factors. Typically, though, a psychiatric diagnosis utilizes a differential diagnosis procedure where a mental status examination and physical examination is conducted, pathological, psychopathological or psychosocial histories obtained, and sometimes neuroimages or other neurophysiological measurements are taken, or personality tests or cognitive tests administered.[101][102][103][104][105][106][107] In some cases, a brain scan might be used to rule out other medical illnesses, but at this time relying on brain scans alone cannot accurately diagnose a mental illness or tell the risk of getting a mental illness in the future.[108] A few psychiatrists are beginning to utilize genetics during the diagnostic process but on the whole this remains a research topic.[109][110][111]

Diagnostic manuals

Three main diagnostic manuals used to classify mental health conditions are in use today. The ICD-10 is produced and published by the World Health Organisation, includes a section on psychiatric conditions, and is used worldwide.[112] The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, produced and published by the American Psychiatric Association, is primarily focused on mental health conditions and is the main classification tool in the United States.[113] It is currently in its fourth revised edition and is also used worldwide.[113] The Chinese Society of Psychiatry has also produced a diagnostic manual, the Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders.[114]

The stated intention of diagnostic manuals is typically to develop replicable and clinically useful categories and criteria, to facilitate consensus and agreed upon standards, whilst being atheoretical as regards etiology.[113][115] However, the categories are nevertheless based on particular psychiatric theories and data; they are broad and often specified by numerous possible combinations of symptoms, and many of the categories overlap in symptomology or typically occur together.[116] While originally intended only as a guide for experienced clinicians trained in its use, the nomenclature is now widely used by clinicians, administrators and insurance companies in many countries.[117]

Treatment settings

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (May 2009) |

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2007) |

General considerations

Individuals with mental health conditions are commonly referred to as patients but may also be called clients, consumers, or service recipients. They may come under the care of a psychiatric physician or other psychiatric practitioners by various paths, the two most common being self-referral or referral by a primary-care physician. Alternatively, a person may be referred by hospital medical staff, by court order, involuntary commitment, or, in the UK and Australia, by sectioning under a mental health law.

Whatever the circumstance of a person's referral, a psychiatrist first assesses the person's mental and physical condition. This usually involves interviewing the person and often obtaining information from other sources such as other health and social care professionals, relatives, associates, law enforcement and emergency medical personnel and psychiatric rating scales. A mental status examination is carried out, and a physical examination is usually performed to establish or exclude other illnesses, such as thyroid dysfunction or brain tumors, or identify any signs of self-harm; this examination may be done by someone other than the psychiatrist, especially if blood tests and medical imaging are performed.

Like all medications, psychiatric medications can cause adverse effects in patients and hence often involve ongoing therapeutic drug monitoring, for instance full blood counts or, for patients taking lithium salts, serum levels of lithium, renal and thyroid function. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is sometimes administered for serious and disabling conditions, especially those unresponsive to medication. The efficacy[118][119] and adverse effects of psychiatric drugs have been challenged.[120]

The close relationship between those prescribing psychiatric medication and pharmaceutical companies has become increasingly controversial[121] along with the influence which pharmaceutical companies are exerting on mental health policies.[122][123]

Also controversial are forced drugging and the "lack of insight" label. According to a report published by the US National Council on Disability,

Involuntary treatment is extremely rare outside the psychiatric system, allowable only in such cases as unconsciousness or the inability to communicate. People with psychiatric disabilities, on the other hand, even when they vigorously protest treatments they do not want, are routinely subjected to them anyway, on the justification that they "lack insight" or are unable to recognize their need for treatment because of their "mental illness". In practice, "lack of insight" becomes disagreement with the treating professional, and people who disagree are labeled "noncompliant" or "uncooperative with treatment".[124]

Inpatient treatment

Psychiatric treatments have changed over the past several decades. In the past, psychiatric patients were often hospitalized for six months or more, with some cases involving hospitalization for many years. Today, people receiving psychiatric treatment are more likely to be seen as outpatients. If hospitalization is required, the average hospital stay is around one to two weeks, with only a small number receiving long-term hospitalization.[citation needed]

Psychiatric inpatients are people admitted to a hospital or clinic to receive psychiatric care. Some are admitted involuntarily, perhaps committed to a secure hospital, or in some jurisdictions to a facility within the prison system. In many countries including the USA and Canada, the criteria for involuntary admission vary with local jurisdiction. They may be as broad as having a mental health condition, or as narrow as being an immediate danger to themselves and/or others. Bed availability is often the real determinant of admission decisions to hard pressed public facilities. European Human Rights legislation restricts detention to medically-certified cases of mental disorder, and adds a right to timely judicial review of detention.[citation needed]

Patients may be admitted voluntarily if the treating doctor considers that safety isn't compromised by this less restrictive option. Inpatient psychiatric wards may be secure (for those thought to have a particular risk of violence or self-harm) or unlocked/open. Some wards are mixed-sex whilst same-sex wards are increasingly favored to protect women inpatients. Once in the care of a hospital, people are assessed, monitored, and often given medication and care from a multidisciplinary team, which may include physicians, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurses, clinical psychologists, psychotherapists, psychiatric social workers, occupational therapists and social workers. If a person receiving treatment in a psychiatric hospital is assessed as at particular risk of harming themselves or others, they may be put on constant or intermittent one-to-one supervision, and may be physically restrained or medicated. People on inpatient wards may be allowed leave for periods of time, either accompanied or on their own.[125]

In many developed countries there has been a massive reduction in psychiatric beds since the mid 20th century, with the growth of community care. Standards of inpatient care remain a challenge in some public and private facilities, due to levels of funding, and facilities in developing countries are typically grossly inadequate for the same reason.[citation needed]

Outpatient treatment

People may receive psychiatric care on an inpatient or outpatient basis. Outpatient treatment involves periodic visits to a clinician for consultation in his or her office, usually for an appointment lasting thirty to sixty minutes. These consultations normally involve the psychiatric practitioner interviewing the person to update their assessment of the person's condition, and to provide psychotherapy or review medication. The frequency with which a psychiatric practitioner sees people in treatment varies widely, from days to months, depending on the type, severity and stability of each person's condition, and depending on what the clinician and client decide would be best. Increasingly, psychiatrists are limiting their practices to psychopharmacology (prescribing medications) with little or no time devoted to psychotherapy or "talk" therapies, or behavior modification. Psychiatrists who serve the lower end of the market, which is dependent on insurance reimbursements, do not receive insurance payments for lengthy psychotherapy sessions which is competitive with that offered for the brief consultations needed for prescribing and monitoring medication. Psychotherapy in such situations is performed by a lower paid psychologist or social worker.[126] The role of psychiatrists is changing in community psychiatry, with many assuming more leadership roles, coordinating and supervising teams of allied health professionals and junior doctors in delivery of health services.[citation needed]

See also

- Biopsychiatry controversy

- Mental health

- Psychiatric assessment

- Telepsychiatry

- Anti-psychiatry

- Bullying in psychiatry

References

Notes

- ^ Etymology of Butterfly

- ^ James, F.E. (1991). "Psyche" (PDF). Psychiatric Bulletin. 15 (7). Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press: 429–431. doi:10.1192/pb.15.7.429. ISBN 0881632570. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ^ Kupfer D.J., Regier D.A. (2010). "Why all of medicine should care about DSM-5". JAMA. 303 (19): 1974–1975. doi:10.1001/jama.2010.646. PMID 20483976.

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 1

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Elkes, A. & Thorpe, J.G. (1967). A Summary of Psychiatry. London: Faber & Faber, p. 13.

- ^ Mohamed Reza Namazi (2001), "Avicenna, 980-1037", American Journal of Psychiatry 158 (11), p. 1796; Mohammadali M. Shoja, R. Shane Tubbs (2007), "The Disorder of Love in the Canon of Avicenna (A.D. 980–1037)", American Journal of Psychiatry 164 (2), pp 228-229;S Safavi-Abbasi, LBC Brasiliense, RK Workman (2007), "The fate of medical knowledge and the neurosciences during the time of Genghis Khan and the Mongolian Empire", Neurosurgical Focus 23 (1), E13, p. 3.

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 4

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 5

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 9

- ^ Bukelic, Jovan (1995). "2". In Mirjana Jovanovic (ed.). Neuropsihijatrija za III razred medicinske skole (in Serbian) (7th ed.). Belgrade: Zavod za udzbenike i nastavna sredstva. p. 7. ISBN 86-17-03418-1.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Borthwick A., Holman C., Kennard D., McFetridge M., Messruther K., Wilkes J. (2001). "The relevance of moral treatment to contemporary mental health care". Journal of Mental Health. 10: 427–439.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Shorter, E. (1997), p. 34

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 35

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 41

- ^ a b c d Shorter, E. (1997), p. 46

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 47

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 48

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 49

- ^ Rothman, D.J. (1990). The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Boston: Little Brown, p. 239. ISBN 978-0-316-75745-4

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 65

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 101

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 102

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 103

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 114

- ^ Cohen, Bruce (2003). Theory and practice of psychiatry. Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 0195149378.

- ^ Thiher, Allen (2005). Revels in Madness: Insanity in Medicine and Literature. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472089994.

- ^ a b c Shorter, E. (1997), p. 145

- ^ a b c Shorter, E. (1997), p. 246

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 270

- ^ Turner T. (2007). "Unlocking psychosis". Brit J Med. 334 (suppl): s7. doi:10.1136/bmj.39034.609074.94. PMID 17204765.

- ^ Cade JFJ. "Lithium salts in the treatment of psychotic excitement". Med J Aust. 1949 (36): 349–352.

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 239

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 273

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 274

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 277

- ^ a b c Shorter, E. (1997), p. 282

- ^ Weiner R.D. (1984). "Does ECT cause brain damage?". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 7: 153.

- ^ Meldrum B.S. (1986). "Neuropathological consequences of chemically and electrically induced seizures". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 462: 18693.

- ^ Dwork A.J., Arango V., Underwood M., Ilievski B., Rosoklija G., Sackeim H.A., Lisanby S.H. (2004). "Absence of histological lesions in primate models of ECT and magnetic seizure therapy". American Journal of Psychiatry. 161 (3): 576–578. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.576. PMID 14992989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Peter R. Breggin, M.D., Electroshock: It's Brain Disabling Effects.

- ^ Dr. Sidney Sament Clinical Psychiatry News, March 1983, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Shorter, E. (1997), p. 280

- ^ Shorter, E. (1997), p. 279

- ^ Semple, David; Smyth, Roger; Burns, Jonathan (2005). Oxford handbook of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 0198527837.

- ^ Noll, Richard (2007). The encyclopedia of schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. Infobase Publishing. p. 3. ISBN 0816064059.

- ^ a b c d Medicine betrayed: the participation of doctors in human rights abuses. Zed Books. 1992. ISBN 1856491048.

- ^ Birley, JL (2000). "Political abuse of psychiatry". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 399 (399): 13–15. PMID 10794019.

- ^ "Press conference exposes mental health genocide during apartheid, 14 June 1997". South African Government Information. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ van Voren R. (2010). "Political Abuse of Psychiatry—An Historical Overview" (PDF). Schizophrenia Bulletin. 36 (1): 33–35. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbp119. PMC 2800147. PMID 19892821.

- ^ Fulford, K; Smirnov, A; Snow, E (1993). "Concepts of disease and the abuse of psychiatry in the USSR". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 162: 801–810. doi:10.1192/bjp.162.6.801. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

- ^ a b c Szasz, Thomas (1994). "Psychiatric diagnosis, psychiatric power and psychiatric abuse" (PDF). Journal of Medical Ethics. 20 (3): 135–138. doi:10.1136/jme.20.3.135. PMC 1376496. PMID 7996558. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Szasz, Thomas (2001). "The Therapeutic State: The Tyranny of Pharmacracy" (PDF). The Independent Review. V (4): 485–521. ISSN 1086-1653. Retrieved 20 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Kershaw, Ian (1999). Hitler: 1889–1936. Norton: New York. ISBN 0393046710.

- ^ White, Kevin (2002). An introduction to the sociology of health and illness. SAGE. p. 42. ISBN 0761964002.

- ^ a b c Manning, Nick (1989). The therapeutic community movement: charisma and routinization. London: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 0415029139.

- ^ Kittrie, Nicholas (1971). The right to be different: deviance and enforced therapy. Johns Hopkins Press. ISBN 0801813190.

- ^ Conrad, Peter; Schneider, Joseph (1992). Deviance and medicalization: from badness to sickness. Temple University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0877229996.

- ^ Sapouna, Lydia; Herrmann, Peter (2006). Knowledge in Mental Health: Reclaiming the Social. Hauppauge: Nova Publishers. p. 70. ISBN 1594548129.

- ^ Metzl, Jonathan (2010). The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease. Beacon Press. p. 14. ISBN 0807085928.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fitzpatrick, Mike (2004). "From 'nanny state' to 'therapeutic state'". The British Journal of General Practice. 1 (54(505)): 645. PMC 1324868. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Arguriou, Petros (2011). Pulp Med. O Books. p. 160. ISBN 1846946999.

- ^ a b Phillips, James; et al. (2012). "The Six Most Essential Questions in Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Pluralogue. Part 1: Conceptual and Definitional Issues in Psychiatric Diagnosis" (PDF). Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine. 7 (3). BioMed Central: 1–51. doi:10.1186/1747-5341-7-3. ISSN 1747-5341. PMID 22243994. Retrieved 24 January 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Slovenko R (2003). "The transinstitutionalization of the mentally ill". Ohio University Law Review. 29: 641.

- ^ Torrey, E.F. (1988). Nowhere to Go: The Tragic Odyssey of the Homeless Mentally Ill. New York: Harper and Row, pp.25-29, 126-128. ISBN 978-0-06-015993-1

- ^ Lyness, J.M. (1997). Psychiatric Pearls. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-80-360280-9[full citation needed]

- ^ a b c d Guze, S. B. (1992), p. 130

- ^ Johann Christian Reil, Dictionary of Eighteenth Century German Philosophers

- ^ British Journal of Psychiatry, Psychiatry’s 200th birthday

- ^ Seminal contributions of Johann Christian Reil

- ^ Guze, S.B. (1992), p. 4

- ^ a b Storrow, H.A. (1969). Outline of Clinical Psychiatry. New York:Appleton-Century-Crofts, p 1. ISBN 978-0-39-085075-1

- ^ Lyness, J.M. (1997), p. 3

- ^ Gask, L. (2004), p. 7

- ^ Guze, S. B. (1992), p 131

- ^ Gask, L. (2004), p. 113

- ^ Gask, L. (2004), p. 128

- ^ a b Pietrini P (2003). "Toward a Biochemistry of Mind?". American Journal of Psychiatry. 160 (11): 1907–1908. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1907. PMID 14594732.

- ^ a b Shorter, E. (1997), p. 326

- ^ Hauser, M.J. (Unknown last update). Student Information. Retrieved September 21, 2007, from http://www.psychiatry.com/student.php

- ^ National Institute of Mental Health. (2006, January 31). Information about Mental Illness and the Brain. Retrieved April 19, 2007, from http://science-education.nih.gov/supplements/nih5/Mental/guide/info-mental-c.htm

- ^ López-Muñoza, Francisco; Alamo, C; Dudley, M; Rubio, G; García-García, P; Molina, JD; Okasha, A (2006-12-07). "Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry: Psychiatry and political–institutional abuse from the historical perspective: The ethical lessons of the Nuremberg Trial on their 60th anniversary". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 31 (4). Cecilio Alamoa, Michael Dudleyb, Gabriel Rubioc, Pilar García-Garcíaa, Juan D. Molinad and Ahmed Okasha. Science Direct: 791. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.12.007. PMID 17223241.

These practices, in which racial hygiene constituted one of the fundamental principles and euthanasia programmes were the most obvious consequence, violated the majority of known bioethical principles. Psychiatry played a central role in these programmes, and the mentally ill were the principal victims.

- ^ Gluzman, S.F. (1991). "Abuse of psychiatry: analysis of the guilt of medical personnel". J Med Ethics. 17 (Suppl): 19–20. doi:10.1136/jme.17.Suppl.19. PMC 1378165. PMID 11651120.

Based on the generally accepted definition, we correctly term the utilisation of psychiatry for the punishment of political dissidents as torture.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Debreu, Gerard (1988). "Part 1: Torture, Psychiatric Abuse, and the Ethics of Medicine". In Corillon, Carol (ed.). Science and Human Rights. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

Over the past two decades the systematic use of torture and psychiatric abuse have been sanctioned or condoned by more than one-third of the nations in the United Nations, about half of mankind.

- ^ The WPA code of ethics.[dead link]

- ^ American Association of Community Psychiatrists About AACP Retrieved on Aug-05-2008

- ^ Verhulst J, Tucker G (1995). "Medical and narrative approaches in psychiatry". Psychiatr Serv. 46 (5): 513–514. PMID 7627683.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c McLaren N (1998). "A critical review of the biopsychosocial model". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 32 (1): 86–92, discussion 93–6. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1614.1998.00343.x. PMID 9565189.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c McLaren, Niall (2007). Humanizing Madness. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 1-932-69039-5.[page needed]

- ^ a b c McLaren, Niall (2009). Humanizing Psychiatry. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. ISBN 1-615-99011-9.[page needed]

- ^ a b About:Psychology. (Unknown last update) Difference Between Psychologists and Psychiatrists. Retrieved March 25, 2007, from http://psychology.about.com/od/psychotherapy/f/psychvspsych.htm

- ^ Hedges, D.; Burchfield, C. (2006). Mind, Brain, and Drug: An Introduction to Psychopharmacology.. Boston: Pearson Education, p. 64,65. ISBN 978-0-205-35556-3

- ^ University of Manchester. (Unknown last update). Research in Psychiatry. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.manchester.ac.uk/research/areas/subareas/?a=s&id=44694

- ^ New York State Psychiatric Institute. (2007, March 15). Psychiatric Research Institute New York State. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://nyspi.org/

- ^ Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation. (2007, July 27). Canadian Psychiatric Research Foundation. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.cprf.ca/

- ^ Elsevier. (2007, October 08). Journal of Psychiatric Research. Retrieved October 13, 2007, from http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/241/description

- ^ Mitchell, J.E.; Crosby, R.D.; Wonderlich, S.A.; Adson, D.E. (2000). Elements of Clinical Research in Psychiatry. Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 978-0-88-048802-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g Katsching, Heinz (2010). "Are psychiatrists an endangered species? Observations on internal and external challenges to the profession". World Psychiatry. 9 (1). World Psychiatric Association: 21–28. PMC 2816922.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Kato, Tadafumi (2011). "A renovation of psychiatry is needed". World Psychiatrу. 10 (3). World Psychiatric Association: 198–199. PMC 3188773.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Rosenhan D (1973). "On being sane in insane places". Science. 179 (4070): 250–258. doi:10.1126/science.179.4070.250. PMID 4683124.

- ^ Spitzer R.L., Lilienfeld S.O., Miller M.B. (2005). "Rosenhan revisited: The scientific credibility of Lauren Slater's pseudopatient diagnosis study". Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 193 (11): 734–739. PMID 16260927.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meyendorf R (1980). "Diagnosis and differential diagnosis in psychiatry and the question of situation referred prognostic diagnosis". Schweizer Archiv Neurol Neurochir Psychiatry für Neurologie, Neurochirurgie et de psychiatrie. 126: 121–134.

- ^ Leigh, H. (1983), p. 15

- ^ Leigh, H. (1983), p. 67

- ^ Leigh, H. (1983), p. 17

- ^ Lyness, J.M. (1997), p. 10

- ^ Hampel H., Teipel S.J., Kotter H.U.; et al. (1997). "Structural magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and research of Alzheimer's disease". Nervenarzt. 68 (5): 365–378. PMID 9280846.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Townsend B.A., Petrella J.R., Doraiswamy P.M. (2002). "The role of neuroimaging in geriatric psychiatry". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 15 (4): 427–432. doi:10.1097/00001504-200207000-00014.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ NIMH publications (2009) Neuroimaging and Mental Illness

- ^ Krebs M.O. (2005). "Future contributions on genetics". World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 6: 49–55. doi:10.1080/15622970510030072. PMID 16166024.

- ^ Benes F.M.; Herold, U; Brocke, B (2007). "An electrophysiological endophenotype of hypomanic and hyperthymic personality". Journal of Affective Disorders. 101 (1–3): 13–26. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.018. PMID 17207536.

- ^ Vonk R., der Schot A.C., Kahn R.S.; et al. (2007). "Is autoimmune thyroiditis part of the genetic vulnerability (or an endophenotype) for bipolar disorder?". Biological Psychiatry. 62 (2): 135–140. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.041. PMID 17141745.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ World Health Organisation. (1992). The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organisation. ISBN 978-9-24-154422-1

- ^ a b c American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition). Washington D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89-042025-6

- ^ Chen Y.F. (2002). "Chinese classification of mental disorders (CCMD-3) towards integration in international classification". Psychopathology. 35 (2–3): 171–175. doi:10.1159/000065140. PMID 12145505.

- ^ Essen-Moller E (1971). "On classification of mental disorders". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 37: 119–126.

- ^ Mezzich J.E. (1979). "Patterns and issues in multiaxial psychiatric diagnosis". Psychological Medicine. 9 (1): 125–137. doi:10.1017/S0033291700021632. PMID 370861.

- ^ Guze S.B. (1970). "The need for toughmindedness in psychiatric thinking". Southern Medical Journal. 63 (6): 662–671. doi:10.1097/00007611-197006000-00012. PMID 5446229.

- ^ Moncrieff et al. (2003). Active placebos versus antidepressants for depression. Cochrane databases.

- ^ Hopper K, Wanderling J (2000). "Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative followup project. International Study of Schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin. 26 (4): 835–46. PMID 11087016.

- ^ Eds. Spiegel D, Lake J. (2006). Complementary And Alternative Treatments in Mental Health Care American Psychiatric Pub, Inc. Quote from p. xxi

- ^ Loren R. Mosher, Richard Gosden and Sharon Beder, 'Drug companies and Schizophrenia: Unbridled Capitalism meets Madness', in Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia edited by John Read, Loren Mosher and Richard Bentall, Brunner-Routledge, New York, 2004, pp. 115-130.

- ^ Richard Gosden and Sharon Beder, 'Pharmaceutical Industry Agenda Setting in Mental Health Policies', Ethical Human Sciences and Services 3(3) Fall/Winter 2001, pp. 147-159

- ^ Thomas Ginsberg. "Donations tie drug firms and nonprofits". The Philadelphia Inquirer 28 May 2006.

- ^ Rae E. Unzicker, Kate P. Wolters, Debra Robinson et al. From Privileges to Rights: People Labeled with Psychiatric Disabilities Speak for Themselves[dead link]. National Council on Disability 20 January 2000.

- ^ Treatment Protocol Project (2003). Acute inpatient psychiatric care: A source book. Darlinghurst, Australia: World Health Organisation. ISBN 0-9578073-1-7. OCLC 223935527.

{{cite book}}: More than one of|author=and|last=specified (help) - ^ Harris, Gardiner (March 5, 2011). "Talk Doesn't Pay, So Psychiatry Turns to Drug Therapy". The New York Times. Retrieved March 6, 2011.

Cited texts

- Gask, L. (2004). A Short Introduction to Psychiatry. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., p. 113 ISBN 978-0-7619-7138-2

- Guze, S.B. (1992). Why Psychiatry Is a Branch of Medicine. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 4. ISBN 978-0-19-507420-8

- Leigh, H. (1983). Psychiatry in the practice of medicine. Menlo Park: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-20-105456-9

- Lyness, J.M. (1997). Psychiatric Pearls. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, p. 3. ISBN 978-0-80-360280-9

- Shorter, E. (1997). A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 978-0-47-124531-5

- Syed, Ibrahim B. (2002). "Islamic Medicine: 1000 years ahead of its times", Journal of the International Society for the History of Islamic Medicine, (2): 2-9 [7-8].

Further reading

- Berrios G E, Porter R (1995) The History of Clinical Psychiatry. London, Athlone Press

- Berrios G E (1996) History of Mental symptoms. The History of Descriptive Psychopathology since the 19th century. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press

- Ford-Martin, Paula Anne Gale (2002), "Psychosis" Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, Farmington Hills, Michigan

- Hirschfeld; et al. (2003). "Perceptions and impact of bipolar disorder: how far have we really come?". J. Clin. Psychiatry. 64 (2): 161–174. doi:10.4088/JCP.v64n0209. PMID 12633125.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - McGorry PD, Mihalopoulos C, Henry L; et al. (1995). "Spurious precision: procedural validity of diagnostic assessment in psychiatric disorders". American Journal of Psychiatry. 152 (2): 220–223. PMID 7840355.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - MedFriendly.com, Psychologist[dead link], Viewed 20 September 2006

- Moncrieff J, Cohen D (2005). "Rethinking models of psychotropic drug action". Psychotherapy & Psychosomatics. 74 (3): 145–153. doi:10.1159/000083999.

- C. Burke, Psychiatry: a "value-free" science? Linacre Quarterly, vol. 67/1 (February 2000), pp. 59–88. [2]

- National Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapists, What is Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy?, Viewed 20 September 2006

- van Os J, Gilvarry C, Bale R et al. (1999) A comparison of the utility of dimensional and categorical representations of psychosis. Psychological Medicine 29 (3) 595-606

- Williams J.B., Gibbon M., First M., Spitzer R., Davies M., Borus J., Howes M., Kane J., Pope H.; et al. (1992). "The structured clinical interview for DSM-III-R (SCID) II: Multi-site test-retest reliability". Archives of General Psychiatry. 49 (8): 630–636. PMID 1637253.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hiruta, Genshiro. (edited by Dr. Allan Beveridge) "Japanese psychiatry in the Edo period (1600-1868)." History of Psychiatry, Vol. 13, No. 50, 131-151 (2002).

External links

- World Psychiatric Association

- Journal of Clinical Psychiatry

- American Psychiatric Association

- The Royal College of Psychiatrists

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists

- Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, official journal of the Pacific Rim College of Psychiatrists.

- Early Intervention in Psychiatry, official journal of the International Early Psychosis Association.

- Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, official journal of The Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology.

- E-Psychiatry Blog