Animal House: Difference between revisions

→Precursors and legacy: If someone can explain what "Rank in Classifies" is or translate it into English, please replace it. |

there's a huge difference between "return" and "gross." No one outside of the studio every knows what the actual return on a film is, just what the estimated gross is. |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

The screenplay was adapted by [[Douglas Kenney]], [[Chris Miller (writer)|Chris Miller]], and [[Harold Ramis]] from stories written by Miller and published in ''National Lampoon'' magazine. The stories were based on Miller's experiences in the [[Alpha Delta Phi]] fraternity at [[Dartmouth College]]. Other influences on the film came from Ramis's experiences in the [[Zeta Beta Tau]] fraternity at [[Washington University in St. Louis]], and producer [[Ivan Reitman]]'s experiences at [[Delta Upsilon]] at [[McMaster University]] in [[Hamilton, Ontario]]. Of the younger lead actors, only [[John Belushi]] was an established star, but even he had not yet appeared in a film, having gained fame mainly from his ''[[Saturday Night Live]]'' television appearances. Several of the actors who were cast as college students, including [[Karen Allen]], [[Tom Hulce]], and [[Kevin Bacon]], were just beginning their film careers, although [[Tim Matheson]] was coming off a large role as one of the assassin [[motorcycle]] cops in the second [[Dirty Harry]] film, ''[[Magnum Force]]''. |

The screenplay was adapted by [[Douglas Kenney]], [[Chris Miller (writer)|Chris Miller]], and [[Harold Ramis]] from stories written by Miller and published in ''National Lampoon'' magazine. The stories were based on Miller's experiences in the [[Alpha Delta Phi]] fraternity at [[Dartmouth College]]. Other influences on the film came from Ramis's experiences in the [[Zeta Beta Tau]] fraternity at [[Washington University in St. Louis]], and producer [[Ivan Reitman]]'s experiences at [[Delta Upsilon]] at [[McMaster University]] in [[Hamilton, Ontario]]. Of the younger lead actors, only [[John Belushi]] was an established star, but even he had not yet appeared in a film, having gained fame mainly from his ''[[Saturday Night Live]]'' television appearances. Several of the actors who were cast as college students, including [[Karen Allen]], [[Tom Hulce]], and [[Kevin Bacon]], were just beginning their film careers, although [[Tim Matheson]] was coming off a large role as one of the assassin [[motorcycle]] cops in the second [[Dirty Harry]] film, ''[[Magnum Force]]''. |

||

Upon its initial release, ''Animal House'' received generally mixed reviews from critics, but ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' and [[Roger Ebert]] proclaimed it one of the year's best. Filmed for $2.8 million, it is one of the most profitable movies of all time, garnering an estimated |

Upon its initial release, ''Animal House'' received generally mixed reviews from critics, but ''[[Time (magazine)|Time]]'' and [[Roger Ebert]] proclaimed it one of the year's best. Filmed for $2.8 million, it is one of the most profitable movies of all time, garnering an estimated gross of more than $141 million in the form of theatrical rentals and home video, not including merchandising. |

||

The film, along with 1977's ''[[The Kentucky Fried Movie]]'', also directed by Landis, was largely responsible for defining and launching the [[Gross out|gross-out genre]] of films, which became one of Hollywood's staples.<ref name="insidestory"/> It is also now considered one of the greatest comedy films ever made by many fans and critics. In 2001, the United States [[Library of Congress]] deemed ''Animal House'' "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the [[National Film Registry]]. It was No. 1 on [[Bravo (US TV network)|Bravo's]] "100 Funniest Movies." It was No. 36 on [[American Film Institute|AFI]]'s "[[AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs|100 Years... 100 Laughs]]" list of the 100 best American comedies. In 2008, ''[[Empire (magazine)|Empire]]'' magazine selected it as one of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time." |

The film, along with 1977's ''[[The Kentucky Fried Movie]]'', also directed by Landis, was largely responsible for defining and launching the [[Gross out|gross-out genre]] of films, which became one of Hollywood's staples.<ref name="insidestory"/> It is also now considered one of the greatest comedy films ever made by many fans and critics. In 2001, the United States [[Library of Congress]] deemed ''Animal House'' "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the [[National Film Registry]]. It was No. 1 on [[Bravo (US TV network)|Bravo's]] "100 Funniest Movies." It was No. 36 on [[American Film Institute|AFI]]'s "[[AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs|100 Years... 100 Laughs]]" list of the 100 best American comedies. In 2008, ''[[Empire (magazine)|Empire]]'' magazine selected it as one of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time." |

||

Revision as of 21:10, 1 December 2013

| National Lampoon's Animal House | |

|---|---|

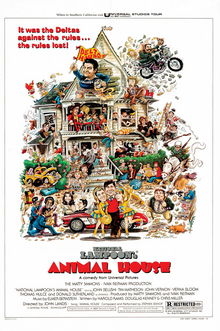

Theatrical release poster designed by Rick Meyerowitz | |

| Directed by | John Landis |

| Written by | Harold Ramis Douglas Kenney Chris Miller |

| Produced by | Ivan Reitman Matty Simmons |

| Starring | John Belushi Tim Matheson John Vernon Verna Bloom Thomas Hulce Donald Sutherland |

| Cinematography | Charles Correll |

| Edited by | George Folsey, Jr. |

| Music by | Elmer Bernstein |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 109 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$3 million[1] |

| Box office | $141,600,000 (US) |

National Lampoon's Animal House is a 1978 American comedy film directed by John Landis. The film was a direct spinoff from National Lampoon magazine. It is about a misfit group of fraternity members who challenge the dean of Faber College.

The screenplay was adapted by Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller, and Harold Ramis from stories written by Miller and published in National Lampoon magazine. The stories were based on Miller's experiences in the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity at Dartmouth College. Other influences on the film came from Ramis's experiences in the Zeta Beta Tau fraternity at Washington University in St. Louis, and producer Ivan Reitman's experiences at Delta Upsilon at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario. Of the younger lead actors, only John Belushi was an established star, but even he had not yet appeared in a film, having gained fame mainly from his Saturday Night Live television appearances. Several of the actors who were cast as college students, including Karen Allen, Tom Hulce, and Kevin Bacon, were just beginning their film careers, although Tim Matheson was coming off a large role as one of the assassin motorcycle cops in the second Dirty Harry film, Magnum Force.

Upon its initial release, Animal House received generally mixed reviews from critics, but Time and Roger Ebert proclaimed it one of the year's best. Filmed for $2.8 million, it is one of the most profitable movies of all time, garnering an estimated gross of more than $141 million in the form of theatrical rentals and home video, not including merchandising.

The film, along with 1977's The Kentucky Fried Movie, also directed by Landis, was largely responsible for defining and launching the gross-out genre of films, which became one of Hollywood's staples.[2] It is also now considered one of the greatest comedy films ever made by many fans and critics. In 2001, the United States Library of Congress deemed Animal House "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. It was No. 1 on Bravo's "100 Funniest Movies." It was No. 36 on AFI's "100 Years... 100 Laughs" list of the 100 best American comedies. In 2008, Empire magazine selected it as one of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time."

Plot

In 1962, college freshmen Lawrence "Larry" Kroger and Kent Dorfman seek to join a fraternity at Faber College. They visit the prestigious Omega Theta Pi House's invitational party, but are not welcomed there. They then try next door at Delta Tau Chi House, where Kent's brother was once a member, making Kent a "legacy." There they find John "Bluto" Blutarsky urinating outside the fraternity house. The Deltas "need the dues" so they permit Larry and Kent to pledge, giving them the fraternity names "Pinto" and "Flounder".

Dean Vernon Wormer wants to remove the Deltas from campus due to repeated conduct violations and low academic standing. Since they are already on probation, he puts the Deltas on something he calls "double secret probation" and orders the clean-cut, smug Omega president Greg Marmalard to find a way to get rid of the Deltas permanently.

Flounder is bullied by Omega member and ROTC cadet commander Doug Neidermeyer, so Bluto and Daniel Simpson "D-Day" Day persuade Flounder to sneak Neidermeyer's horse into Dean Wormer's office late at night. They give him a gun and tell him to shoot it. Unbeknownst to Flounder, the gun is loaded with blanks. Unable to bring himself to kill the horse, he fires into the ceiling. The noise frightens the horse so much that it dies of a heart attack.

In the cafeteria the next day, smooth-talking Eric "Otter" Stratton tries to convince the stuck-up Mandy Pepperidge to abandon her boyfriend, Marmalard, and date him instead. Bluto proceeds to provoke Marmalard with his impression of a popping zit by stuffing his mouth with a scoop of mashed potatoes and propelling it at Marmalard and table mates, Chip Diller and Barbara "Babs" Jansen. Bluto then starts a food fight that engulfs the cafeteria.

Bluto and D-Day steal the answers to an upcoming psychology test, but it turns out the Omegas planted the exam mimeograph and the Deltas get every answer wrong. Their grade-point averages drop so low that Wormer needs only one more incident to revoke the charter that allows them to remain on campus.

To cheer themselves up, the Deltas organize a toga party, during which Otis Day and the Knights perform "Shout". The dean's wife, Marion, attends the party at Otter's invitation and has sex with him. Pinto hooks up with Clorette, a girl he met at the supermarket, and makes out with her only to learn she is the mayor's 13-year-old daughter. He later takes her home in a shopping cart. Wormer organizes a kangaroo court with the Omegas and revokes Delta's charter.

To take their minds off their troubles, Otter, Donald "Boon" Schoenstein, Flounder and Pinto go on a road trip. Otter picks up some girls from Emily Dickinson College by pretending to be the fiancé of Fawn Liebowitz, a girl who recently died on campus. They stop at a roadhouse because Otis Day and the Knights are performing there, not realizing that it caters to an exclusively black clientele. The hulking patrons intimidate the guys and they flee, damaging Flounder's borrowed car and leaving their frightened dates behind.

Boon breaks up with his girlfriend Katy after discovering her sexual relationship with a professor. Marmalard is told that his girlfriend is having an affair with Otter, so he and other Omegas lure him to a motel and beat him up. The Deltas' midterm grades are so poor that an ecstatic Wormer expels them all. He even notifies their draft boards of their eligibility. In the process, before Bluto attempts to speak to the dean, Wormer orders Flounder to speak, whereupon Flounder vomits on the dean.

It seems time for the Deltas to give up, but Bluto, supported by the injured Otter, rouses them with an impassioned, historically inaccurate speech ("Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor?!") and they decide to take revenge on Wormer and the Omegas. The Deltas construct a rogue parade float with Flounder's car as its base and wreak havoc on the annual homecoming parade. During the ensuing chaos, the futures of many of the main characters are revealed. At the end, Bluto is seen driving away in a white convertible with Mandy Pepperidge.

Cast

Delta Tau Chi (ΔΤΧ)

- John Belushi as John "Bluto" Blutarsky: A drunken degenerate with his own style, in his seventh year of college,[3] with a GPA of 0.0. The film epilogue reveals that he eventually became a United States senator.

- Tim Matheson as Eric "Otter" Stratton: A smooth playboy whose room is a pristine seduction den amid the sheer filth of the rest of the Delta house. Otter is the fraternity's rush chairman and essentially the fraternity's unofficial leader. He becomes a gynecologist in Beverly Hills.

- Peter Riegert as Donald "Boon" Schoenstein: Otter's best friend, who has to decide between his Delta pals and girlfriend Katy. He marries Katy in 1964, but they divorce in 1969. In the book adaptation Boon becomes a cab driver and part-time writer in New York City. In "Where Are They Now?" he and Katy remarried, re-divorced, and remarried a final time after a fling resulted in the conception of their son Otis; he also works as a documentarian.

- Thomas Hulce as Lawrence "Pinto" Kroger: A shy but normal fellow, who becomes the editor of National Lampoon magazine. "Pinto" was screenwriter Chris Miller's nickname at his Dartmouth fraternity.[2]

- Stephen Furst as Kent "Flounder" Dorfman: An overweight, clumsy legacy pledge, later a sensitivity trainer in Cleveland.

- Bruce McGill as Daniel Simpson Day, "D-Day": A tough biker with no grade point average; all classes incomplete. His later whereabouts are unknown.

- James Widdoes as Robert Hoover: The affable, reasonably clean-cut president of the fraternity, who desperately struggles to maintain a façade of normality to placate the Dean. These efforts usually end with him willingly going along with the Delta lifestyle. He is at the top of his fraternity with a 1.6 grade point average with 4 C's and one F. He becomes a public defender in Baltimore.

- Douglas Kenney as "Stork": During his first year, everyone thought the Stork was brain damaged; he only speaks two lines in the entire film. In the book adaptation, Stork is revealed to be independently wealthy as a result of several patents he holds. In "Where Are They Now?" he has died.

Omega Theta Pi (ΩΘΠ)

- James Daughton as Gregory "Greg" Marmalard: The president of Omega House and boyfriend of Mandy Pepperidge. He suffers from erectile dysfunction. He becomes a Nixon White House aide and is subsequently raped in prison in 1974.

- Mark Metcalf as Douglas C. Neidermeyer: An ROTC cadet officer and scion of a military family who hates the Deltas. He is fragged (killed by his own platoon) in Vietnam.

- Kevin Bacon as Chip Diller: A smarmy Omega pledge who is trampled by the panicking crowd at the end of the movie. In "Where Are They Now?" he became a born-again Christian missionary in Africa.

Supporting characters

- John Vernon as Dean Vernon Wormer: Dean of Faber College. He wants to revoke the Deltas' charter and kick them off campus because of their partying ways. In "Where Are They Now?" he was fired after the Homecoming parade debacle and is now in a nursing home.

- Verna Bloom as Marion Wormer: The Dean's alcoholic wife, who attends the toga party and is shown going to bed with Otter. In the graphic novel written by Chris Miller, she wins the "Miss Congeniality" prize at the climactic toga party and is shown wearing a toilet seat painted to look like a garland of flowers.

- Donald Sutherland as Professor Dave Jennings: A bored English professor who tries to turn his students on to left-wing politics and smoking marijuana. In the "Where Are They Now?," it is revealed he became Chairman of Faber's English Department the same year that Dean Wormer entered the nursing home.

- Karen Allen as Katy: Boon's frustrated girlfriend who has a dalliance with Jennings but subsequently goes on to marry, then divorce, Boon. In the "Where Are They Now?" it is revealed find out she and Boon remarried then re-divorced then re-re-married.

- Sarah Holcomb as Clorette DePasto: The mayor's 13-year-old daughter.

- DeWayne Jessie as Otis Day: The leader of the band that plays at the toga party. Jessie adopted the Day name in his private life and toured with the band.[2]

- Mary Louise Weller as Mandy Pepperidge: A cheerleader and sorority girl who dates Greg, but is not satisfied with the relationship. She later marries Bluto.

- Martha Smith as Barbara Sue "Babs" Jansen: A Southern belle who wants Greg for herself and finds the Deltas repulsive. After being indecently exposed in public by the Deltas she becomes a tour guide at Universal Studios Hollywood.

- Cesare Danova as Mayor Carmine DePasto: The shady local mayor with suggested mafia ties.

- Sean McCartin as "Lucky Boy": The Playboy-reading child who shouts "Thank you, God!" after a Playboy Bunny flies through his bedroom window onto his bed. McCartin later became pastor of a Eugene church.[2]

- Stephen Bishop as Charming Guy with Guitar on stairs at toga party who gets his guitar smashed by Bluto.

- Blues musician Robert Cray had an uncredited, non-speaking, role as a bassist in Otis Day's band.

Production

Origins

Animal House was the first film produced by National Lampoon, the most popular humor magazine on college campuses in the mid-1970s.[4] The periodical specialized in humor, and satirized politics and popular culture. Many of the magazine’s writers were recent college graduates, hence their appeal to students all over the country. In 1974, Dave Mobley was impressed with the magazine and wrote a short story about Mu Omega Beta (the MOB) of Union College. The MOB was started in 1966 as an anti fraternity. The college was a religious school that didn't allow drinking or partying. Mu Omega Beta would supply the party house and the booze. Each MOB member would be given a secret name, known only to its members. The purpose was to know who ordered what on the "beer list." If list got into the wrong hands, no one would be identified to the school. The MOB was known for pranks, wild parties and other crazy behavior. Freshmen women were warned to stay away from the MOB, which made them seek out Mu Omega Beta members. The story was received by National Lampoon; they loved the story of the MOB and set their writers loose on the idea.

Doug Kenney was a Lampoon writer and the magazine’s first editor-in-chief. He graduated from Harvard University in 1969 and had a college experience closer to the Omegas in the film (he had been president of the university's elite Spee Club).[4] Kenney was responsible for the first appearances of three characters that would appear in the film, Larry Kroger, Mandy Pepperidge and Vernon Wormer. They made their debut in 1975's National Lampoon’s High School Yearbook, a satire of a Middle America 1964 high school yearbook. Kroger's and Pepperidge's characters in the yearbook were effectively the same as their characters in the movie, whereas Vernon Wormer was a P.E. and civics teacher as well as an athletic coach in the yearbook.

However, Kenney felt that fellow Lampoon writer Chris Miller was the magazine's expert on the college experience.[4] Faced with an impending deadline, Miller submitted a chapter from his then-abandoned memoirs entitled "The Night of the Seven Fires" about pledging experiences from his fraternity days in Alpha Delta (associated with the national Alpha Delta Phi during Miller's undergraduate years, the fraternity subsequently disassociated itself from the national organization and is now called Alpha Delta) at the Ivy League's Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire. The antics of his fellow fraternities became the inspiration for the Delta Tau Chis of Animal House and many characters in the film (and their nicknames) were based on Miller's fraternity brothers.[4] Miller's college nickname was "Pinto" in recognition of dark spots he had on a certain private part of his anatomy. Filmmaker Ivan Reitman had just finished producing David Cronenberg's first film, Shivers, and called the magazine’s publisher Matty Simmons about making movies under the Lampoon banner.[5] Reitman had put together The National Lampoon Show in New York City featuring several future Saturday Night Live cast members, including John Belushi. When most of the Lampoon group moved on to SNL except for Harold Ramis, Reitman approached him with an idea to make a film together using some skits from the Lampoon Show.[5]

Screenplay

Kenney met Lampoon writer Ramis at the suggestion of Simmons. Ramis drew from his own fraternity experiences as a member of Zeta Beta Tau fraternity at Washington University in St. Louis and was working on a treatment about college called "Freshman Year", but the magazine’s editors were not happy with it.[4] Kenney and Ramis started working on a treatment together, positing Charles Manson in a high school, calling it Laser Orgy Girls.[5] Simmons was cool to this idea so they changed the setting to a "northeastern college ... Ivy League kind of school."[2] Kenney was a fan of Miller’s fraternity stories and suggested using them as a basis for a movie. Kenney, Miller and Ramis began brainstorming ideas.[5] They saw the film's 1962 setting as "the last innocent year ... of America", and the homecoming parade that ends the film as occurring on November 21, 1963, the day before President Kennedy's assassination.[2] They agreed that Belushi should star in it and Ramis wrote the part of Bluto specifically for the comedian, having met him at Chicago's The Second City.[6]

The writers were new to screenwriting,[2] and thus produced a 110-page treatment (the average was 15 pages) that Reitman and Simmons pitched to various Hollywood studios. Simmons met with Ned Tanen, an executive at Universal Studios. He was encouraged by younger executives Sean Daniel and Thom Mount who were more receptive to the Lampoon type of humor.[4] Tanen hated the idea. Ramis remembers, "We went further than I think Universal expected or wanted. I think they were shocked and appalled. Chris' fraternity had virtually been a vomiting cult. And we had a lot of scenes that were almost orgies of vomit ... We didn't back off anything".[5] As the writers created more drafts of the screenplay (nine in total), the studio gradually became more receptive to the project, especially Mount, who championed it.[7] Surprisingly, the studio green-lighted the film and set the budget at a modest $3 million.[4] Simmons remembers, "They just figured, ‘Screw it, it’s a silly little movie, and we’ll make a couple of bucks if we’re lucky — let them do whatever they want.’"[5]

Casting

Initially, Reitman had wanted to direct but had made only one film, Cannibal Girls, for $5,000.[5] The film's producers approached Richard Lester and Bob Rafelson before considering John Landis, who got the director job based on his work on Kentucky Fried Movie.[7] That film’s script and continuity supervisor was the girlfriend of Sean Daniel, an assistant to Mount. Daniel saw Landis’ movie and recommended him. Landis then met with Mount, Reitman and Simmons and got the job.[5] Landis remembers, "When I was given the script, it was the funniest thing I had ever read up to that time. But it was really offensive. There was a great deal of projectile vomiting and rape and all these things".[8] There was also a certain amount of friction between Landis and the writers early on because Landis was a high-school dropout from Hollywood and they were college graduates from the East Coast. Ramis remembers, "He sort of referred immediately to Animal House as ‘my movie.’ We’d been living with it for two years and we hated that".[5] According to Landis, he drew inspiration from classic Hollywood comedies featuring the likes of Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and the Marx Brothers.[9]

The initial cast was to feature Chevy Chase as Otter, Bill Murray as Boon, Brian Doyle-Murray as Hoover, Dan Aykroyd as D-Day and John Belushi as Bluto, but only Belushi wanted to do it. Chase was a star from Saturday Night Live, which had recently become a cultural phenomenon.[5] His name would have added credibility to the project, but he turned the film down to do Foul Play;[5] Landis, who wanted to cast unknown[2] dramatic actors[5] such as Bacon and Allen (the first film for both) instead of famous comedians,[5] takes credit for subtly discouraging Chase by describing the film as an "ensemble".[2] The character of D-Day was based on Aykroyd, who was a motorcycle aficionado. Aykroyd was offered the part, but he was already committed to Saturday Night Live.[7] Belushi—who had worked on The National Lampoon Radio Hour before Saturday Night Live[2]—was also committed to the show, but spent Monday through Wednesday making the film and then flying back to New York to do the show on Thursday through Saturday.[6] Ramis originally wrote the role of Boon for himself, but Landis felt that he looked too old for the part and Riegert was cast instead. Landis did offer Ramis a smaller part, but he declined. Landis met with Jack Webb to play Dean Wormer and Kim Novak to play his wife. Webb ultimately backed out due to concerns over his clean-cut image, and was replaced by John Vernon.[5]

Belushi received only $35,000 for Animal House, with a bonus after it became a hit.[6] Landis also met with Meat Loaf in case Belushi did not want to play Bluto. Landis worked with Belushi on his character, who "hardly had any dialogue";[2][3] they decided that Bluto was a cross between Harpo Marx and the Cookie Monster.[2] Despite Belushi's presence, Universal wanted another star. Landis had been a crew member on Kelly's Heroes and had become friends with actor Donald Sutherland, sometimes babysitting his son Kiefer.[5] Landis asked Sutherland, one of the biggest stars of the 1970s, to be in the film. For two days' work, Sutherland initially declined $35,000. Universal then offered him $35,000 and 15% of the film's gross, assuming that the movie would be quickly forgotten. Sutherland wanted guaranteed money and settled for $50,000; although this made him the highest-paid member of the cast (other than Neidemeyer's horse[2]), the decision cost Sutherland what Landis estimates as "at least $20 million."[5]

Locations

The filmmakers' next problem was finding a college that would let them shoot the film on their campus.[5] They submitted the script to a number of colleges and universities but "nobody wanted this movie" due to the script; according to Landis, "I couldn't find 'the look'. Every place that had 'the look' said, 'no thank you.'"[2]

The president of the University of Oregon in Eugene, William Beaty Boyd,[10] had been a senior administrator of a major California university when his campus was considered for a location of the film The Graduate.[5] After he consulted with other senior administrative colleagues who advised him to turn it down due to the lack of artistic merit, production moved to Berkeley and USC. The Graduate went on to become a classic, and Boyd was determined not to make the same mistake twice when the producers inquired about filming at Oregon. After consulting with student government leaders and officers of the Pan Hellenic Council, the Director of University Relations advised the president that the script, although raunchy and often tasteless, was a very funny spoof of college life. Boyd even allowed the filmmakers to use his office as Dean Wormer's.[5]

The actual house depicted as the Delta House was originally a residence in Eugene, the Dr. A.W. Patterson House. Around 1959, it was acquired by the Psi Deuteron chapter of Phi Sigma Kappa fraternity and was their chapter house until 1967, when the chapter was closed due to low membership. The house was sold and slid into disrepair, with the spacious porch removed and the lawn graveled over. At the time of the shooting, the Phi Kappa Psi and Sigma Nu fraternity houses sat next to the old Phi Sigma Kappa house. The interior of the Sigma Nu house was used for many of the interior scenes, but the individual rooms were filmed on a soundstage. The Patterson house was demolished in 1986.[11] The site is now occupied by Northwest Christian University's school of Education and Counseling. A large boulder placed to the west of the parking entrance displays a bronze plaque commemorating the Delta House location. The parade scene takes place in downtown Cottage Grove, Oregon on Main Street.

Principal photography

Landis brought the actors who played the Deltas up five days early in order to bond. Staying at the Rodeway Inn they moved an old piano from the lobby into McGill's room, which became known as "party central".[5] Actor James Widdoes remembers, "It was like freshman orientation. There was a lot of getting to know each other and calling each other by our character names".[5] This tactic encouraged the actors playing the Deltas to separate themselves from the actors playing the Omegas, helping generate authentic animosity between them on camera.[5] Belushi and his wife, Judy, had a house in the suburbs in order to keep him away from alcohol and drugs.[5]

Although the cast members were warned against mixing with the college students,[2] one night, some girls invited several of the cast members to a fraternity party. They arrived assuming they had been invited and were greeted with open hostility.[5] As they were leaving, Widdoes threw a cup of beer at a group of drunk football players and a fight "like a scene from the movie"[2] broke out. Tim Matheson, Bruce McGill, Peter Riegert, and Widdoes narrowly escaped, with McGill suffering a black eye and Widdoes getting several teeth knocked out.[5]

Other than Belushi's opening yell, the food fight was filmed in one shot, with the actors encouraged to fight for real.[2] Flounder's groceries handling in the supermarket was another single shot; Furst deftly caught the many items Landis and Matheson threw at him, amazing the director.[2]

While shooting the film, Landis and Bruce McGill staged a scene for reporters visiting the set where the director pretended to be angry at the actor for being difficult on the set.[12] Landis grabbed a breakaway pitcher and smashed it over McGill's head. He fell to the ground and pretended to be unconscious. The reporters were completely fooled, and when Landis asked McGill to get up, he refused to move.[12]

Black extras had to be bused in from Portland for the segment at the Dexter Lake Club due to their scarcity around Eugene. More seriously, the segment alarmed studio executives, who perceived it as racist and warned that "'black people in America are going to rip the seats out of theaters if you leave that scene in the movie.'" Richard Pryor's approval helped retain the segment in the film.[2] The studio became more enthusiastic about the film when Reitman showed executives and sales managers of various regions in the country a 10-minute production reel that was put together in two days.[7] The reaction was positive and the studio sent 20 copies out to exhibitors.[7] The first preview screening for Animal House was held in Denver four months before it opened nationwide. The crowd loved it and the filmmakers realized they had a potential hit on their hands.[5]

Soundtrack and score

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

The soundtrack is a mix of rock and roll and rhythm and blues with the original score created by film composer Elmer Bernstein, who had been a Landis family friend since John Landis was a child.[13] Bernstein was easily persuaded to score the film, but was not sure what to make of it. Landis asked him to score it as though it were serious. Bernstein said that his work on this film opened yet another door in his diverse career, to scoring comedies.[13]

The soundtrack was released as a vinyl album in 1978, and then as a CD in 1998.

Soundtrack album listing

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performed by | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Faber College Theme" | Elmer Bernstein | Elmer Bernstein | 0:35 |

| 2. | "Louie, Louie" | Richard Berry | John Belushi | 2:56 |

| 3. | "Twistin' the Night Away" | Sam Cooke | Sam Cooke | 2:39 |

| 4. | "Tossin' and Turnin'" | Richie Adams, Malou Rene | Bobby Lewis | 2:49 |

| 5. | "Shama Lama Ding Dong" | Mark Davis | Lloyd Williams (Otis Day and the Knights) | 2:48 |

| 6. | "Hey Paula" | Raymound Hildebrand | Paul & Paula | 2:47 |

| 7. | "Animal House" | Stephen Bishop | Stephen Bishop | 3:41 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Performed by | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Intro" | — | — | 0:49 |

| 2. | "Money (That's What I Want)" | Berry Gordy, Jr., Janie Bradford | John Belushi | 2:31 |

| 3. | "Let's Dance" | Jim Lee | Chris Montez | 2:28 |

| 4. | "Dream Girl" | Stephen Bishop | Stephen Bishop | 4:34 |

| 5. | "(What a) Wonderful World" | Sam Cooke, Herb Alpert, Lou Adler | Sam Cooke | 2:06 |

| 6. | "Shout" | Ronald Isley, Rudolph Isley, O'Kelly Isley | Lloyd Williams (Otis Day and the Knights) | 5:04 |

| 7. | "Faber College Theme" | Elmer Bernstein | Elmer Bernstein | 1:16 |

Additional music in the film

- "Theme from A Summer Place", composed by Max Steiner; performed by Percy Faith and his Orchestra

- "Who's Sorry Now?", written by Ted Snyder, Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby; performed by Connie Francis

- "The Washington Post March", composed by John Philip Sousa

- "Tammy", by Jay Livingston and Ray Evans

Reaction

On its opening weekend, Animal House grossed $276,538, in 12 theaters.[14] The film grossed over $1,000,000 per week, becoming the second most popular 1978 US film, trailing only Grease.[15] It made $120.1 million in North America and went on to have a domestic lifetime gross of $141.6 million.[14]

Critical reception

At the time of its release, Animal House received mixed reviews from critics[2] but several immediately recognized its appeal,[16] and it has since been recognized as one of the best films of 1978.[17][18][19][20] The film currently holds a 90% "Certified Fresh" rating on the review aggregate website Rotten Tomatoes.[21] Roger Ebert gave the film four stars out of four and wrote, "It's anarchic, messy, and filled with energy. It assaults us. Part of the movie's impact comes from its sheer level of manic energy... But the movie's better made (and better acted) than we might at first realize. It takes skill to create this sort of comic pitch, and the movie's filled with characters that are sketched a little more absorbingly than they had to be, and acted with perception".[3] Ebert later placed the film on his 10 best list of 1978, the first and only National Lampoon film to have received this honor.[22] In his review for Time, Frank Rich wrote, "At its best it perfectly expresses the fears and loathings of kids who came of age in the late '60s; at its worst Animal House revels in abject silliness. The hilarious highs easily compensate for the puerile lows".[23] Gary Arnold wrote in his review for The Washington Post, "Belushi also controls a wicked array of conspiratorial expressions with the audience... He can seem irresistibly funny in repose or invest minor slapstick opportunities with a streak of genius".[24] David Ansen wrote in Newsweek, "But if Animal House lacks the inspired tastelessness of the Lampoon's High School Yearbook Parody, this is still low humor of a high order".[25] Robert Martin wrote in The Globe and Mail, "It is so gross and tasteless you feel you should be disgusted but it's hard to be offended by something that is so sidesplittingly funny".[26] Time magazine proclaimed Animal House one of the year's best.[27]

When the film was released, Landis, Widdoes and Allen went on a national promotional tour.[12] Universal Pictures spent about $4.5 million promoting the film at selected college campuses and helped students organize their own toga parties.[28][29] One such party at the University of Maryland attracted some 2,000 people, while students at the University of Wisconsin–Madison tried for a crowd of 10,000 people and a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.[29] Thanks to the film, toga parties became one of 1978's favorite college campus happenings.[6]

American Film Institute Lists

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs—#36

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Songs:

- Shout—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- "Toga! Toga!"—#82

- "Over? Did you say “over?” Nothing is over until we decide it is! Was it over when the Germans bombed Pearl Harbor? Hell, no!"—Nominated

- "Fat, drunk, and stupid is no way to go through life, son."—Nominated

- AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)—Nominated

Spin-offs

The film inspired a short-lived half-hour ABC television sitcom, Delta House, in which Vernon reprised his role as the long-suffering, malevolent Dean Wormer. The series also included Stephen Furst as Flounder, Bruce McGill as D-Day, and James Widdoes as Hoover.[30] The pilot episode was written by the film's screenwriters, Douglas Kenney, Chris Miller and Harold Ramis.[31] Michelle Pfeiffer made her acting debut in the series (playing a new character, "Bombshell"), and Peter Fox was cast as Otter. John Belushi's character from the film, John "Bluto" Blutarsky, is in the army, but his brother, Blotto, played by Josh Mostel, transfers to Faber to carry on Bluto's tradition.[31]

Animal House inspired Co-Ed Fever, another sitcom but without the involvement of the film's producers or cast.[30] Set in a dorm of the formerly all-female Baxter College, the pilot of Co-Ed Fever was aired by CBS on February 4, 1979, but the network canceled the series before airing any more episodes.[32] NBC also had its Animal House-inspired sitcom, Brothers and Sisters, in which three members of Crandall College's Pi Nu fraternity interact with members of the Gamma Iota sorority.[30] Like ABC's Delta House, Brothers and Sisters lasted only three months.[33]

The film's writers planned a movie sequel set in 1967 (the so-called "Summer of Love"), in which the Deltas have a reunion for Pinto's marriage in Haight-Ashbury, San Francisco.[34] The only Delta to have become a hippie is Flounder, who is now called Pisces. Later, Chris Miller and John Weidman, another Lampoon writer, created a treatment for this screenplay, but Universal rejected it because the sequel to American Graffiti, which contained some hippie-1967 sequences, had not done well. When John Belushi died, the idea was indefinitely shelved.[34]

A second attempt at a sequel was made in 1982 with producer Matty Simmons co-authoring a script which saw some of the Deltas returning to Faber College five years after the events of the film. The project got no further than a first draft script dated May 6, 1982.[35]

The "Double Secret Probation Edition" DVD included a short film entitled "Where Are They Now?: A Delta Alumni Update" which suggested the film had been a documentary and Landis was catching up with some of the cast (played by their original actors).

"Where Are They Now?"

Where Are They Now?: A Delta Alumni Update is a 2002 mockumentary film for Universal. It was never shown in theaters, but was included only on the 2003 "Double Secret Probation Edition" DVD release. It shows the main characters from National Lampoon's Animal House 30 years on, and purports that the original film had been a documentary. The mockumentary follows director John Landis to cities all over America in search of the former Deltas, Omegas, and Dean Wormer. Here are the various locales and professions the characters have settled into:

- Donald Schoenstein – Film editor, New York City. Currently in his third marriage to Katy. He has a son named Otis.

- Babs Jansen – Tour guide, Universal Studios, Hollywood. She mentions to Landis that she is organizing an upcoming Faber reunion, and seems to be successful at her job.

- Marion Wormer – Seemingly unemployed in Chicago. She tells Landis of how her husband Vernon accepted the blame for the parade debacle, and was subsequently fired, leading to their divorce. She becomes progressively more tipsy throughout the interview, eventually falling off her chair.

- Kent Dorfman – Executive director, Encounter Groups of Cleveland, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. He recalls trying to diet during the 1970s with a special program requiring him to shoot up the urine of pregnant women.

- Robert Hoover – Assistant district attorney, Baltimore, Maryland. Hoover tells the tale of how he quit being a public defender after he realized many of his clients were insane. He also boasts of how his legal advice was sought during the O.J. Simpson murder case.

- Chip Diller – Landis receives a letter from Diller, who is currently serving as a missionary in Africa. He recalls how he was prevented from going to Vietnam as his father was a prime donor to several right-wing political campaigns. When he learned of Doug Neidermeyer's fragging in Vietnam, he fell into alcoholism and despair. When he began seeing Jesus in his food, he became a born-again Christian and fell into his current profession as minister and missionary.

- Dean Vernon Wormer – Wormer is seen at a nursing home in Florida, under the watchful eye of a male nurse. He appears to be senile, not recognizing Landis at first (calling him "Larry"), and not remembering his tenure as Dean of Faber. When Landis mentions the Deltas, Wormer erupts into a violent, profanity-laced tirade against the boys who cost him his job. He lashes out against the nurse and then physically attacks Landis, knocking out the camera in the process.

- Eric Stratton – Gynecologist, Beverly Hills, California. Otter is depicted as still being the affable, suave gentleman he was in his college days. He remarks that gynecology has been very enjoyable for him and that he has straightened up a bit since leaving Faber. An attractive, blonde patient in her underwear then tells Otter she's ready for her examination. Otter politely cuts the interview off and goes into the exam room.

- Daniel Simpson Day – Landis remarks in a voiceover that D-Day has been the hardest to track down for the documentary, saying that rumors have flown around, with his whereabouts ranging from a Buddhist monastery in Nepal to the Yukon Territory. Landis eventually approaches a house in Modesto, California, where a man opens the door by a crack and claims, in a Hispanic accent, "I don't know no D-Day person! I don't know him!" He slams the door in Landis' face and then bursts out of the garage in a car. He pulls out onto the street to the strains of the William Tell Overture, gives a manic laugh exactly like D-Day's, and speeds off.

- John Blutarsky – In a final voice-over a shot of the White House, Landis remarks that the viewers all know what happened to Bluto and Mandy Pepperidge: they became the President and First Lady of the United States.

Home video

Animal House became one of the most profitable movies of all time. Since its initial release, the film has garnered an estimated return of more than $141 million in the form of video and DVDs, not including merchandising.

Animal House was released on videodisc in 1979.[36] A Collector's Edition DVD was released in 2002, with a 30-minute 1998 documentary entitled "The Yearbook – An Animal House Reunion" by producer JM Kenny with production notes, theatrical trailer, and new interviews with director Landis, stars Tim Matheson, Karen Allen, Peter Riegert, Mark Metcalf and Kevin Bacon.[37] The "Double Secret Probation Edition" DVD released in 2003 features cast members reprising their respective roles in a "Where Are They Now?" mockumentary, which posited the original film as a documentary. One major change shown in this mockumentary from the epilogue of the original film is that Bluto went on from his career in the U.S. Senate to become the President of the United States, with a voiceover on a shot of the north portico of the White House, since by then Belushi had died. This DVD also includes "Did You Know That? Universal Animated Anecdotes," a subtitle trivia track, the making of documentary from the Collector's Edition, MXPX "Shout" music video, a theatrical trailer, production notes, and cast and filmmakers biographies.[38] In August 2006, the film was released on an HD DVD/DVD combo disc, which featured the film in a 1080p high-definition format on one side, and a standard-definition format on the opposite side.[39] Along with the film Unleashed, Animal House was one of Universal's first two HD/DVD combo releases,[40] but was later discontinued in 2008 after Universal decided to switch to the Blu-ray Disc format following the conclusion of the high definition optical disc format war.[41]

It is currently available on Blu-ray.[42]

Precursors and legacy

It was a great box office success despite its limited production costs and thus started an industry trend,[9] inspiring countless other comedies such as Porky's, the Police Academy films, the American Pie films, and Old School among others.[4][9] On the left-wing and counterculture side, it included references to topical political matters like Kent State shootings, President Harry S. Truman's decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Richard Nixon, the Vietnam war and the civil rights movement.[4] Precursors of this counterculture subversive humor in film were two non "college movies", M*A*S*H, a 1970 satirical dark comedy, and The Kentucky Fried Movie, a 1977 formless comedy consisting of a series of sketches.[9]

In 2012, Universal Pictures Stage Productions announced it was developing a stage musical version of the movie. Barenaked Ladies will write the score, and Casey Nicholaw will direct;[43] author Michael Mitnick is also reportedly involved.[44]

In 2001, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film culturally significant and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[45] Animal House is first on Bravo's 100 Funniest Movies.[46] In 2000, the American Film Institute ranked the film No. 36 on 100 Years... 100 Laughs, a list of the 100 best American comedies.[47] In 2006, Miller wrote a more comprehensive memoir of his experiences in Dartmouth's AD house in a book entitled, The Real Animal House: The Awesomely Depraved Saga of the Fraternity That Inspired the Movie, in which Miller recounts hijinks that were considered too risqué for the movie. In 2008, Empire magazine selected Animal House as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[48] The film was also selected by The New York Times as one of The 1000 Best Movies Ever Made.[49]

See also

- Rick Meyerowitz, the illustrator who drew the Animal House poster.

References

- ^ Lee, Grant (February 15, 1979). "Box-Office Power: 'Animal House' Earns Respect". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Animal House: The Inside Story. August 13, 2008.

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1978). "National Lampoon's Animal House". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Peterson, Molly (July 29, 2002). "National Lampoon's Animal House". National Public Radio. Retrieved February 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Nashawaty, Chris (July 29, 2002). "Building Animal House". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 31, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Schwartz, Tony (October 23, 1978). "College Humor Comes Back". Newsweek. p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e Medjuck, Joe (July 1978). "The Further Adventures of Ivan Reitman". Take One.

- ^ Olson, Eric (October 23, 1978). "Director, John Landis: The Dean Speaks". Digital Movie Talk.

- ^ a b c d Mitchell, Elvis (August 25, 2003). "Revisiting Faber College (Toga, Toga, Toga!)". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ "Presidential History | Office of the President". President.uoregon.edu. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "On Film". University of Oregon Archives. October 23, 1978. Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c Arnold, Gary (August 13, 1978). "The Madcap World of John Landis". The Washington Post. pp. H1.

- ^ a b Kenny, J.M (1998). "The Yearbook: An Animal House Reunion". Animal House: Collector's Edition DVD. Universal Studios.

- ^ a b "National Lampoon's Animal House". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ "All Time Top Grossing Movies". IMDB. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ "Animal House Movie Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "The Greatest Films of 1978". AMC Filmsite.org. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "The 10 Best Movies of 1978". Film.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "The Best Movies of 1978 by Rank". Films101.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Most Popular Feature Films Released in 1978". IMDb.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Animal House Movie Reviews, Pictures". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Ebert's 10 Best Lists: 1967–present". The Chicago Sun Times. April 29, 2003. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ Rich, Frank (August 14, 1978). "School Days". Time. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (August 11, 1978). "National Lampoon's Animal House: Bringing the Beast Out of the Fraternity". The Washington Post. pp. B1.

- ^ Ansen, David (August 7, 1978). "Gross Out". Newsweek. p. 85.

- ^ Martin, Robert (August 5, 1978). "Animal House – A Lampoon Zoo". Globe and Mail. Canada.

- ^ "Year's Best". Time. January 1, 1979. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ "Bed Sheets Bonanza". Time. October 23, 1978. Retrieved August 20, 2008.

- ^ a b Darling, Lynn (September 26, 1978). "TOGA! TOGA! TOGA!: The Toga Party, Popping Up on Campuses Across the Country". The Washington Post. pp. C1.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Waters, Harry F (January 29, 1979). "Send in the Clones". Newsweek. p. 85.

- ^ a b Shales, Tom (January 18, 1979). "Bluto's Gone but His Brother's Carrying On". The Washington Post. pp. B15.

- ^ "Co-ed Fever: Episode Listings". TV.com. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ "Brothers and Sisters (1979): Episode Listings". TV.com. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Quindlen, Anna (September 5, 1980). "Young Actor Weary of Lying About Age". New York Times.

- ^ "Script Review: Animal House 2". FilmBuffOnline. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ "Disc Duel". Time. February 19, 1979. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (September 4, 1998). "House Rules". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Kim, Wook (September 5, 2003). "National Lampoon's Animal House Double Secret Probation Edition". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 21, 2008.

- ^ Bracke, Peter M (August 7, 2006). "National Lampoon's Animal House (HD DVD)". High-Def Digest. Internet Brands. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Bracke, Peter M (June 26, 2007). "Unleashed (Re-issue) (HD DVD)". High-Def Digest. Internet Brands. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Lambert, David (February 19, 2008). "Site News – Universal Switching From HD DVD to Blu-ray Disc *UPDATED*". TVShowsOnDVD.com. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ National Lampoon's Animal House [Blu-ray]. "National Lampoon's Animal House [Blu-ray]: John Belushi, Tom Hulce, John Landis: Movies & TV". Amazon.com. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Casey Nicholaw to Helm New ANIMAL HOUSE Musical; Barenaked Ladies to Write Score!". BroadwayWorld.com. March 5, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ "Toga Party on Broadway! "Animal House" Being Made Into Stage Musical". Playbill.com. March 5, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ^ "Films Selected to The National Film Registry, Library of Congress 1989–2006". National Film Registry. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- ^ "Bravo's 100 Funniest Movies of All Time". listal.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs" (PDF). AFI.com. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Empire's The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire Magazine. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made". The New York Times. April 29, 2003. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

Further reading

- Hoover, Eric (2008) "Animal House" at 30: O Bluto, Where Art Thou?, Chronicle of Higher Education, v55 n2 pA1 Sep 2008

- Daniel P. Franklin (2006) Politics and film: the political culture of film in the United States, pp. 133–4

- Krista M. Tucciarone (2007) Cinematic College: "National Lampoon's Animal House" Teaches Theories of Student Development, in Journal of College Student Development

External links

- Official website

- Miller '63 reveals the real history of 'Animal House'

- Animal House at IMDb

- Animal House at AllMovie

- Animal House at Box Office Mojo

- Animal House at Rotten Tomatoes

- Animal House at Metacritic

- 1978 films

- 1978 soundtracks

- 1970s comedy films

- American films

- American sex comedy films

- American teen comedy films

- English-language films

- Films about fraternities and sororities

- Films directed by John Landis

- Films set in 1962

- Films set in the 1960s

- Film soundtracks

- Films shot in Oregon

- MCA Records soundtracks

- National Lampoon films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Universal Pictures films

- Screenplays by Harold Ramis

- Screenplays by Douglas Kenney

- Screenplays by Chris Miller (writer)

- Cottage Grove, Oregon

- Eugene, Oregon

- Lane County, Oregon