Hasan-i Sabbah: Difference between revisions

Kansas Bear (talk | contribs) Undid revision 802321454 by 66.114.19.210 (talk) |

Rescuing 1 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.6) |

||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Hassan’s takeover of the fort was conducted without any significant bloodshed. To effect this transition Hassan employed a patient and deliberate strategy, one which took the better part of two years to effect. First Hassan sent his ''Daʻiyyīn'' and ''Rafīk''s to win over the villages in the valley, and their inhabitants. Next, key people amongst this populace were converted, and finally, in 1090, Hassan took over the fort by infiltrating it with his converts.<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Farhad Daftary|Daftary]]|first=[[Farhad Daftary|Farhad]]|chapter=Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period |title=The [[Ismā'īlī]]s: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=September 2007 |isbn=978-0-521-61636-2 |page=317}}</ref> Hassan gave the former owner a draft drawn on the name of a wealthy landlord and told him to obtain the promised money from this man; when the landlord saw the draft with Hassan’s signature, he immediately paid the amount to the fort's owner, astonishing him. Another, probably apocryphal version of the takeover states that Hassan offered 3000 gold dinars to the fort's owner for the amount of land that would fit a buffalo’s hide. The terms having been agreed upon, Hassan cut the hide into strips and linked them into a large ring around the perimeter of the fort, whose owner was thus undone by his own greed. This story bears a striking resemblance to [[Virgil]]'s account of [[Dido (Queen of Carthage)|Dido's]] founding of [[Carthage]]. |

Hassan’s takeover of the fort was conducted without any significant bloodshed. To effect this transition Hassan employed a patient and deliberate strategy, one which took the better part of two years to effect. First Hassan sent his ''Daʻiyyīn'' and ''Rafīk''s to win over the villages in the valley, and their inhabitants. Next, key people amongst this populace were converted, and finally, in 1090, Hassan took over the fort by infiltrating it with his converts.<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Farhad Daftary|Daftary]]|first=[[Farhad Daftary|Farhad]]|chapter=Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period |title=The [[Ismā'īlī]]s: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=September 2007 |isbn=978-0-521-61636-2 |page=317}}</ref> Hassan gave the former owner a draft drawn on the name of a wealthy landlord and told him to obtain the promised money from this man; when the landlord saw the draft with Hassan’s signature, he immediately paid the amount to the fort's owner, astonishing him. Another, probably apocryphal version of the takeover states that Hassan offered 3000 gold dinars to the fort's owner for the amount of land that would fit a buffalo’s hide. The terms having been agreed upon, Hassan cut the hide into strips and linked them into a large ring around the perimeter of the fort, whose owner was thus undone by his own greed. This story bears a striking resemblance to [[Virgil]]'s account of [[Dido (Queen of Carthage)|Dido's]] founding of [[Carthage]]. |

||

While legend holds that after capturing Alamut Hassan thereafter devoted himself so faithfully to study, that in the nearly 35 years he was there he never left his quarters, excepting only two times when he went up to the roof. This reported isolation is highly doubtful, given his extensive recruiting and organizational involvement in the growing Ismā'īlī insurrections in Persia and Syria.<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Farhad Daftary|Daftary]]|first=[[Farhad Daftary|Farhad]]|chapter=Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period |title=The [[Ismā'īlī]]s: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=September 2007 |isbn=978-0-521-61636-2 |pages=318–324}}</ref> Nonetheless, Hassan was highly educated and was known for austerity, studying, translating, praying, fasting, and directing the activities of the Daʻwa: the propagation of the Nizarī doctrine was headquartered at Alamut. He knew the [[Qur'ān]] by heart, could quote extensively from the texts of most Muslim sects, and apart from philosophy, was well versed in [[mathematics]], [[astronomy]], [[alchemy]], [[medicine]], [[architecture]], and the major scientific disciplines of his time.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chnpress.com/news/?section=2&id=2786 |title=Hassan Sabbah Dabbled in Astronomy: Experts |publisher=Chnpress.com |date= |accessdate=2012-01-30}}</ref> In a major departure from tradition, Hassan declared Persian to be the language of holy literature for Nizaris, a decision that resulted in all the Nizari Ismā'īlī literature from Persia, Syria, Afghanistan and Central Asia to be transcribed in Persian for several centuries.<ref name="Daftary 316"/> |

While legend holds that after capturing Alamut Hassan thereafter devoted himself so faithfully to study, that in the nearly 35 years he was there he never left his quarters, excepting only two times when he went up to the roof. This reported isolation is highly doubtful, given his extensive recruiting and organizational involvement in the growing Ismā'īlī insurrections in Persia and Syria.<ref>{{cite book |last=[[Farhad Daftary|Daftary]]|first=[[Farhad Daftary|Farhad]]|chapter=Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period |title=The [[Ismā'īlī]]s: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition |publisher=Cambridge University Press |date=September 2007 |isbn=978-0-521-61636-2 |pages=318–324}}</ref> Nonetheless, Hassan was highly educated and was known for austerity, studying, translating, praying, fasting, and directing the activities of the Daʻwa: the propagation of the Nizarī doctrine was headquartered at Alamut. He knew the [[Qur'ān]] by heart, could quote extensively from the texts of most Muslim sects, and apart from philosophy, was well versed in [[mathematics]], [[astronomy]], [[alchemy]], [[medicine]], [[architecture]], and the major scientific disciplines of his time.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.chnpress.com/news/?section=2&id=2786 |title=Hassan Sabbah Dabbled in Astronomy: Experts |publisher=Chnpress.com |date= |accessdate=2012-01-30 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20111017030312/http://www.chnpress.com/news/?section=2 |archivedate=17 October 2011 |df=dmy-all }}</ref> In a major departure from tradition, Hassan declared Persian to be the language of holy literature for Nizaris, a decision that resulted in all the Nizari Ismā'īlī literature from Persia, Syria, Afghanistan and Central Asia to be transcribed in Persian for several centuries.<ref name="Daftary 316"/> |

||

From this point on his community and its branches spread throughout [[Iran]] and [[Syria]] and came to be called [[Hashshashin]] or [[Assassins]], also known as the Fedayin (Meaning 'The Martyrs', or 'Men Who Accept Death').{{citation needed|date=October 2013}} |

From this point on his community and its branches spread throughout [[Iran]] and [[Syria]] and came to be called [[Hashshashin]] or [[Assassins]], also known as the Fedayin (Meaning 'The Martyrs', or 'Men Who Accept Death').{{citation needed|date=October 2013}} |

||

Revision as of 03:23, 31 October 2017

Hassan-e Sabbah | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Mawla of Alamut[1] |

| Personal | |

| Born | circa 1034, Qom, Persia |

| Died | 12 June 1124 (26 Rabi'o-Saani 518), Alamut Castle, Nizari Ismaili State Persia (c. aged 89) |

| Jurisprudence | Islam |

| Main interest(s) | Islamic theology, Islamic jurisprudence, Islamic law |

| Senior posting | |

Influenced | |

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

Hassan-e Sabbāh (mistakenly Hassan-i Sabbāh Persian: حسن صباح Hasan-e Sabbāh) or Hassan al-Sabbāh (Arabic: حسن الصباح Ḥasan aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ) (circa 1034-1124) was a Nizārī Ismā‘īlī missionary who converted a community in the late 11th century in the heart of the Alborz Mountains of northern Persia. He later seized a mountain fortress called Alamut. He founded a group of fedayeen whose members are often referred to as the Hashshashin, or "Assassins".[2]

Sources

Hassan is thought to have written an autobiography, which did not survive but seems to underlie the first part of an anonymous Isma'ili biography entitled Sargozasht-e Seyyednā (Persian: سرگذشت سیدنا). The latter is known only from quotations made by later Persian authors.[3] Hassan also wrote a treatise, in Persian, on the doctrine of ta'līm, called, al-Fusul al-arba'a[4] The text is no longer in existence, but fragments are cited or paraphrased by al-Shahrastānī and several Persian historians.[4]

Early life and conversion

Qom and Rayy

The possibly autobiographical information found in Sargozasht-i Seyyednā is the main source for Hassan's background and early life. According to this, Hassan-e Sabbāh was born in the city of Qom (Iran) in the 1050s to an family of Twelver Shī‘ah.[3] His father claimed Yemenite origins, who left the Sawād of Kufa hej (modern Iraq) to settle in the (predominantly Shi'a) town of Qom.[5][6]

Early in his life, his family moved to Rayy.[3] Rayy was a city that had a history of radical Islamic thought since the 9th century, with Hamdan Qarmaṭ as one of its teachers.

It was in this religious centre that Hassan developed a keen interest in metaphysical matters and adhered to the Twelver code of instruction. During the day[7] he studied at home, and mastered palmistry, languages, philosophy, astronomy and mathematics (especially geometry).[8]

Rayy was also the home of Ismā‘īlī missionaries in the Jibal. At the time, Isma'ilism was a growing movement in Persia and other lands east of Egypt.[9] The Persian Isma'ilis supported the da'wa ("mission") directed by the Fatimid caliphate of Cairo and recognized the authority of the Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir (d. 1094), though Isfahan, rather than Cairo, may have functioned as their principal headquarters.[9] The Ismā'īlī mission worked on three layers: the lowest was the foot soldier or fidā'ī, followed by the rafīk or "comrade", and finally the Dā‘ī or "missionary". It has been suggested that the popularity of the Ismā'īlī religion in Persia was due to the people's dissatisfaction with the Seljuk rulers, who had recently removed local rulers.[3]

In Rayy, a young Hassan came in touch with Amira Darrab, a comrade, who introduced him to the Ismā'īlī doctrine. Hassan was initially unimpressed, his interest gradually grew after participating in many passionate debates that discussed the merits of Ismā‘īl over Mūsā. Seeing the conviction of Darrab, convinced Hassan to delve deeper into Ismā'īlī doctrines and beliefs, ultimately convincing him to see merit in switching to the Ismā‘īlī faith.

Conversion to Ismailism and training in Cairo

At the age of 17, Hassan converted and swore allegiance to the Fatimid Caliph in Cairo. Hassan's studies did not end with his crossing over. He further studied under two other dā‘iyyayn, and as he proceeded on his path, he was looked upon with eyes of respect.

Hassan's austere and devoted commitment to the da'wa brought him in audience with the chief missionary of the region: ‘Abdu l-Malik ibn Attash. Ibn Attash, suitably impressed with the young seventeen-year-old Hassan, made him Deputy Missionary and advised him to go to Cairo to further his studies.

However, Hassan did not go to Cairo. Some historians have postulated that Hassan, following his conversion, was playing host to some members of the Fatimid caliphate, and this was leaked to the anti-Fatimid and anti-Shī‘a vizier Nizam al-Mulk. This prompted his abandoning Rayy and heading to Cairo in 1076.

Hassan took about 2 years to reach Cairo. Along the way he toured many other regions that did not fall in the general direction of Egypt. Isfahan was the first city that he visited. He was hosted by one of the Missionaries of his youth, a man who had taught the youthful Hassan in Rayy. His name was Resi Abufasl and he further instructed Hassan.

From here he went to Caucasian Albania (current Azerbaijan), hundreds of miles to the north, and from there through Armenia. Here he attracted the ire of priests following a heated discussion, and Hassan was thrown out of the town he was in.

He then turned south and traveled through Iraq, reached Damascus in Syria. He left for Egypt from Palestine. Records exist, some in the fragmentary remains of his autobiography, and from another biography written by Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in 1310, to date his arrival in Egypt at 30 August 1078.

It is unclear how long Hassan stayed in Egypt: about 3 years is the usually accepted amount of time. He continued his studies here, and became a full missionary.

Return to Persia

Whilst he was in Cairo, studying and preaching, he incurred the displeasure of the Chief of the Army, Badr al-Jamalī.[10] This may have been a result of the fact that Hassan supported Nizar, the Ismaili Imam-Caliph al-Mustanṣir's elder son, as the next Imam. Hassan was briefly imprisoned by Badr al-Jamali. The collapse of a minaret of the jail was taken to be an omen in favor of Hassan and he was promptly released and deported.[citation needed] The ship that he was traveling on was wrecked. He was rescued and taken to Syria. Traveling via Aleppo and Baghdad, he terminated his journey at Isfahan in 1081.

Hassan's life now was totally devoted to the mission. Hassan toured extensively throughout Persia. In northern Persia, touching the south shore of the Caspian Sea, are the mountains of Alborz. These mountains were home to a people who had traditionally resisted attempts by both Arabs and Turkish subjugation; this place was also a home of Shī‘a leaning. The news of this Ismā'īlī's activities reached Nizam al-Mulk, who dispatched his soldiers with the orders for Hassan's capture. Hassan evaded them, and went deeper into the mountains.

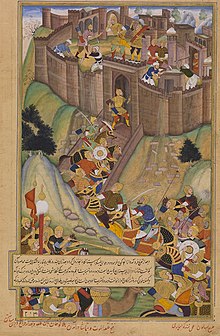

Capture of Alamut

His search for a base from which to guide his mission ended when in 1088 he found the castle of Alamut in the Rudbar area (modern 'Qazvin, Iran'). It was a fort that stood guard over a valley that was about fifty kilometers long and five kilometers wide. This fortress had been built about the year 865; legend has it that it was built by a king who saw his eagle fly up to and perch upon a rock, a propitious omen, the importance of which this king, Wah Sudan ibn Marzuban, understood. Likening the perching of the eagle to a lesson given by it, he called the fort Aluh Amu(kh)t: the "Eagles' Teaching".[11]

Hassan’s takeover of the fort was conducted without any significant bloodshed. To effect this transition Hassan employed a patient and deliberate strategy, one which took the better part of two years to effect. First Hassan sent his Daʻiyyīn and Rafīks to win over the villages in the valley, and their inhabitants. Next, key people amongst this populace were converted, and finally, in 1090, Hassan took over the fort by infiltrating it with his converts.[12] Hassan gave the former owner a draft drawn on the name of a wealthy landlord and told him to obtain the promised money from this man; when the landlord saw the draft with Hassan’s signature, he immediately paid the amount to the fort's owner, astonishing him. Another, probably apocryphal version of the takeover states that Hassan offered 3000 gold dinars to the fort's owner for the amount of land that would fit a buffalo’s hide. The terms having been agreed upon, Hassan cut the hide into strips and linked them into a large ring around the perimeter of the fort, whose owner was thus undone by his own greed. This story bears a striking resemblance to Virgil's account of Dido's founding of Carthage.

While legend holds that after capturing Alamut Hassan thereafter devoted himself so faithfully to study, that in the nearly 35 years he was there he never left his quarters, excepting only two times when he went up to the roof. This reported isolation is highly doubtful, given his extensive recruiting and organizational involvement in the growing Ismā'īlī insurrections in Persia and Syria.[13] Nonetheless, Hassan was highly educated and was known for austerity, studying, translating, praying, fasting, and directing the activities of the Daʻwa: the propagation of the Nizarī doctrine was headquartered at Alamut. He knew the Qur'ān by heart, could quote extensively from the texts of most Muslim sects, and apart from philosophy, was well versed in mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, medicine, architecture, and the major scientific disciplines of his time.[14] In a major departure from tradition, Hassan declared Persian to be the language of holy literature for Nizaris, a decision that resulted in all the Nizari Ismā'īlī literature from Persia, Syria, Afghanistan and Central Asia to be transcribed in Persian for several centuries.[11]

From this point on his community and its branches spread throughout Iran and Syria and came to be called Hashshashin or Assassins, also known as the Fedayin (Meaning 'The Martyrs', or 'Men Who Accept Death').[citation needed]

Representation in music

A song on Hawkwind's 1977 album Quark, Strangeness and Charm is titled Hassan I Sabbah.

See also

Notes

- ^ Persian: خداوند الموت Khudāwand-i Alamūt

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (1967), The Assassins: a Radical Sect of Islam, pp 30-31, Oxford University Press

- ^ a b c d Daftary, Farhad, The Isma'ilis, p. 311.

- ^ a b Farhad Daftary, Ismaili Literature: A Bibliography of Sources and Studies, (I.B.Tauris, 2004), 115.

- ^ Lewis, Bernard (November 2002). "3. The New Preaching". The Assassins. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00498-0.

Hasan-i Sabbah was born in the city of Qumm, a stronghold of Twelver Shi'ism. His father, a Twelver Shi'ite, had come from Kufa in Iraq, and was said to be of Yemeni origin.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Daftary, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

His father, 'Ali b. Muhammad b. Ja'far b. al-Husayn b. Muhammad b. al-Sabbah al-Himyari, a Kufan claiming Yamani origins, had migrated from the Sawad of Kufa to the traditionally Shi'i town of Qumm in Persia.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Nizam al-Mulk Tusi, pg. 420, foot note No. 3

- ^ E. G. Brown Literary History of Persia, Vol. 1, pg. 201.

- ^ a b Daftary, Farhad, The Isma'ilis, pp. 310-11.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 313. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ a b Daftary, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Daftary, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ Daftary, Farhad (September 2007). "Nizari Isma'ili history during the Alamut period". The Ismā'īlīs: Their History and Doctrines 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 318–324. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|first=value (help) - ^ "Hassan Sabbah Dabbled in Astronomy: Experts". Chnpress.com. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011. Retrieved 30 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)

References

- Firdous-a-iblees by anayat ullah

Secondary sources

- Daftary, Farhad, The Isma'ilis: Their History and Doctrines. 2nd ed (1990). Cambridge et al., 2007.

- Irwin, Robert. "Islam and the Crusades, 1096–1699". In The Oxford History of the Crusades, ed. Jonathan Riley Smith. Oxford, 2002. 211–57.

Further reading

- Firdous-a-iblees by anayat ullah

Primary sources

- Hassan-i Sabbah, al-Fuṣūl al-arba'a ("The Four Chapters"), tr. Marshall G.S. Hodgson, in Ismaili Literature Anthology. A Shi'i Vision of Islam, ed. Hermann Landolt, Samira Sheikh and Kutub Kassam. London, 2008. pp. 149–52. Persian treatise on the doctrine of ta'līm. The text is no longer extant, but fragments are cited or paraphrased by al-Shahrastānī and several Persian historians.

- Sarguzasht-e Sayyidnā

- Nizam al-Mulk

- al-Ghazali

Secondary sources

- Daftary, Farhad, A Short History of the Ismā'īlīs. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1998.

- Daftary, Farhad, The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismā'īlīs. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 1994. Reviewed by Babak Nahid at Ismaili.net

- Daftary, Farhad, "Hasan-i Sabbāh and the Origins of the Nizārī Ismā'īlī movement." In Mediaeval Ismā'īlī History and Thought, ed. Farhad Daftary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 181–204.

- Hodgson, Marshall, The Order of Assassins. The Struggle of the Early Nizārī Ismā'īlī Against the Islamic World. The Hague: Mouton, 1955.

- Hodgson, Marshall, "The Ismā'īlī State." In The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 5: The Saljuq and Mongol Periods, ed. J.A. Boyle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968. 422–82.

- Lewis, Bernard, The Assassins. A Radical Sect in Islam. New York: Basic Books, 1968.

- Madelung, Wilferd, Religious Trends in Early Islamic Iran. Albany: Bibliotheca Persica, 1988. 101–5.

External links

- HASAN BIN SABBAH AND NIZARI ISMAILI STATE IN ALAMUT

- The life of Hassan-i-Sabah from an Ismaili point of view. Focuses on assassination as a tactic of asymmetrical warfare and has a small section on Hasan-i-Sabah's work as a scholar.

- Introduction to The Assassin Legends (From The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma‘ilis, London: I. B. Tauris, 1994; reprinted 2001.)

- The life of Hassan-i-Sabbah as part of an online book on the Assassins of Alamut.

- Arkon Daraul on Hassan-i-Sabbah.

- An illustrated article on the Order of Assassins.

- William S. Burrough's invocation of Hassan-i-Sabbah in Nova Express.

- Assassins entry in the Encyclopedia of the Orient.

- Review of the book, "The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis (I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd: London, 1994), 213 pp." by Babak Nahid, Department of Comparative Literature, University of California, Los Angeles