Zina

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) |

|---|

|

| Islamic studies |

Zināʾ (زِنَاء) or zinah (زِنًى or زِنًا) is an Islamic legal term referring to unlawful sexual intercourse.[1] According to traditional jurisprudence, zinah can include adultery[2][3][4] (of married parties), fornication[2][3][4] (of unmarried parties), prostitution,[5] rape,[1] sodomy,[2][6] homosexuality,[7][6] incest,[8][9] and bestiality.[2][10] Although classification of homosexual intercourse as zina differs according to legal school,[11] the majority apply the rules of zinā to homosexuality,[12][13] mostly male homosexuality.[14]

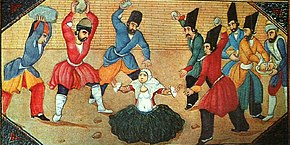

Zina belongs the the category of hudud offenses (sing.: hadd), which are offenses that are specifically mentioned in the Quran, also known as "claims of God" (huqūq Allāh). Several verses of the of the Quran prohibit zina, including 24:2 which says it should be punished with 100 lashes. However, on the basis of hadith, the penalty for an offender who is muhsan (adult, free, Muslim, and married at least once) is stoning to death (rajm). Zina must be proved by testimony of four male Muslim eyewitnesses to the actual act of penetration, or a confession repeated four times and not retracted later.[15][1] The offenders must have acted of their own free will.[1] Rapists could be prosecuted under different legal categories which used normal evidentiary rules.[16] Making an accusation of zina without presenting the required eyewitnesses is called qadhf (القذف), which is itself a hudud offense.[17]

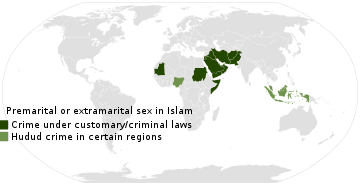

There are very few recorded examples of the stoning penalty for zināʿ being implemented legally. Prior to legal reforms introduced in several countries during the 20th century, the procedural requirements for proving the offense of zināʿ to the standard necessary to impose the stoning penalty were effectively impossible to meet [1][18] Zina became a more pressing issue in modern times, as Islamist movements and governments employed polemics against public immorality.[1] During the Algerian Civil War, Islamist insurgents assassinated women suspected of loose morals, the Taliban have executed suspected adultresses using machine guns, and zina has been used as justification for honor killings.[1] After sharia-based criminal laws were widely replaced by European-inspired statutes in the modern era, in recent decades several countries passed legal reforms that incorporated elements of hudud laws into their legal codes.[19] Iran witnessed several highly publicized stonings for zina in the aftermath of the Islamic revolution.[1] In Nigeria, local courts have passed several stoning sentences, all of which were overturned on appeal or left unenforced.[20] In Pakistan, the Hudood Ordinances of 1979 subsumed prosecution of rape under the category of zina, making rape extremely difficult to prove and exposing the victims to jail sentences for admitting illicit intercourse forced upon them.[1][16] Although these laws were amended in 2006,[18] and again in 2016.[21] According to human rights organizations, stoning for zina has also been carried out in Saudi Arabia.[11]

Islamic scriptures

Muslim scholars have historically considered zināʾ a hudud sin, or crime against God.[22] It is mentioned in both Quran and in the Hadiths.[23]

Introduction and definition

The Qur'an deals with zināʾ in several places. First is the Qur'anic general rule that commands Muslims not to commit zināʾ:

"Nor come nigh to fornication/adultery: for it is a shameful (deed) and an evil, opening the road (to other evils)."

In the Hadiths, the definitions of zina have been described as all the forms of sexual intercourse, penetrative or non-penetrative, outside the institution marriage or the institution of slavery.[25]

Abu Huraira reported Allah's Apostle as saying: “Allah has decreed for every son of Adam his share of zina, which he will inevitably commit. The zina of the eyes is looking, the zina of the tongue is speaking, one may wish and desire, and the private parts confirm that or deny it.”

Adultery and fornication

Qur'an

Most of the rules related to fornication, adultery and false accusations from a husband to his wife or from members of the community to chaste women, can be found in Surat an-Nur (the Light). The sura starts by giving very specific rules about punishment for zināʾ:

"The woman and the man guilty of zināʾ (for fornication or adultery),- flog each of them with a hundred stripes: Let not compassion move you in their case, in a matter prescribed by Allah, if ye believe in Allah and the Last Day: and let a party of the Believers witness their punishment."

"And those who accuse chaste women then do not bring four witnesses, flog them, (giving) eighty stripes, and do not admit any evidence from them ever; and these it is that are the transgressors. Except those who repent after this and act aright, for surely Allah is Forgiving, Merciful."

Hadith

The public lashing and public lethal stoning punishment for fornication and adultery are also prescribed in Hadiths, the books most trusted in Islam after Quran, particularly in Kitab Al-Hudud.[28][29][not specific enough to verify]

'Ubada b. as-Samit reported: Allah's Messenger as saying: Receive teaching from me, receive teaching from me. Allah has ordained a way for those women. When an unmarried male commits adultery with an unmarried female, they should receive one hundred lashes and banishment for one year. And in case of married male committing adultery with a married female, they shall receive one hundred lashes and be stoned to death.

— 17:4191

Ma'iz came to the Prophet and admitted having committed adultery four times in his presence so he ordered him to be stoned to death, but said to Huzzal: If you had covered him with your garment, it would have been better for you.

— 38:4364

Hadith Sahih al Bukhari, another authentic source of sunnah, has several entries which refer to death by stoning.[30] For example,

Narrated 'Aisha: 'Utba bin Abi Waqqas said to his brother Sa'd bin Abi Waqqas, "The son of the slave girl of Zam'a is from me, so take him into your custody." So in the year of Conquest of Mecca, Sa'd took him and said. (This is) my brother's son whom my brother has asked me to take into my custody." 'Abd bin Zam'a got up before him and said, (He is) my brother and the son of the slave girl of my father, and was born on my father's bed." So they both submitted their case before Allah's Apostle. Sa'd said, "O Allah's Apostle! This boy is the son of my brother and he entrusted him to me." 'Abd bin Zam'a said, "This boy is my brother and the son of the slave girl of my father, and was born on the bed of my father." Allah's Apostle said, "The boy is for you, O 'Abd bin Zam'a!" Then Allah's Apostle further said, "The child is for the owner of the bed, and the stone is for the adulterer," He then said to Sauda bint Zam'a, "Veil (screen) yourself before him," when he saw the child's resemblance to 'Utba. The boy did not see her again till he met Allah.

— 9:89:293

Other hadith collections on zina between men and woman include:

- The stoning (Rajm) of a Jewish man and woman for having committed illegal sexual intercourse.[31]

- Abu Hurairah states that the Prophet, in a case of intercourse between a young man and a married woman, sentenced the woman to stoning[32] and the young man to flogging and banishment for a year;

Rape

Rape has been defined as zina al-zibr (forcefull illicit sex) in the traditional Islamic texts. Few hadiths have been found regarding rape in the time of Muhammad. The most popular transmitted hadith given below indicates the ordinance of stoning for the rapist but no punishment and no requirement of four eyewitnesses for the rape victim.[33][34]

When a woman went out in the time of the Prophet for prayer, a man attacked her and overpowered (raped) her. She shouted and he went off, and when a man came by, she said: That (man) did such and such to me. And when a company of the emigrants came by, she said: That man did such and such to me. They went and seized the man whom they thought had had intercourse with her and brought him to her. She said: Yes, this is he. Then they brought him to the Messenger of Allah. When he (the Prophet) was about to pass sentence, the man who (actually) had assaulted her stood up and said: Messenger of Allah, I am the man who did it to her. He (the Prophet) said to her: Go away, for Allah has forgiven you. But he told the man some good words (AbuDawud said: meaning the man who was seized), and of the man who had had intercourse with her, he said: Stone him to death. He also said: He has repented to such an extent that if the people of Medina had repented similarly, it would have been accepted from them.

The hadiths declare rape of a free or slave woman as zina.[35]

View of scholars

Malik related to me from Nafi that a slave was in charge of the slaves in the khumus and he forced a slave-girl among those slaves against her will and had intercourse with her. Umar ibn al-Khattab had him flogged and banished him, and he did not flog the slave-girl because the slave had forced her.

Malik related to me from Ibn Shihab that gave a judgment that the rapist had to pay the raped woman her bride-price. Yahya said that he heard Malik say, "What is done in our community about the man who rapes a woman, virgin or non-virgin, if she is free, is that he must pay the bride-price of the like of her. If she is a slave, he must pay what he has diminished of her worth. The hadd-punishment in such cases is applied to the rapist, and there is no punishment applied to the raped woman. If the rapist is a slave, that is against his master unless he wishes to surrender him."

— 36 16.14

If a confession or the four witnesses required to prove a hadd crime are not available, but rape can be proved by other means, the rapist is sentenced under the ta'zir system of judicial discretion.[37] According to the eleventh-century Maliki jurist Ibn 'Abd al-Barr:[37]

The scholars are unanimously agreed that the rapist is to be subjected to the hadd punishment if there is clear evidence against him that he deserves the hadd punishment, or if he admits to that. Otherwise, he is to be punished (i.e., if there is no proof that the hadd punishment for zina may be carried out against him because he does not confess, and there are not four witnesses, then the judge may punish him and stipulate a punishment that will deter him and others like him). There is no punishment for the woman if it is true that he forced her and overpowered her, which may be proven by her screaming and shouting for help.

— Al-Istidhkaar

Homosexuality

Islamic teachings (in the hadith tradition[38]) presume same-sex attraction, extol abstention and (in the Qur'an[39][38]) condemn consummation. The Quran forbids homosexual relationships, in Al-Nisa, Al-Araf (verses 7:80–84, 11:69–83, 29:28–35 of the Qur'an using the story of Lot's people), and other surahs. For example,[39][38][40]

We also sent Lot: He said to his people: "Do ye commit lewdness such as no people in creation (ever) committed before you? For ye practice your lusts on men in preference to women: ye are indeed a people transgressing beyond bounds."

In another verse, the statement of prophet lot has been also pointed out,

Do you approach males among the worlds And leave what your Lord has created for you as mates? But you are a people transgressing.

— Quran 26:165–166, trans. Sahih International

Some scholars indicate this verse as the prescribed punishment for homosexuality in the Quran:

"If two (men) among you are guilty of lewdness, punish them both. If they repent and amend, Leave them alone; for Allah is Oft-returning, Most Merciful."

However, there are different interpretations of the last verse where who the Quran refers to as "two among you". Pakistani scholar Javed Ahmed Ghamidi sees it as a reference to premarital sexual relationships between men and women. In his opinion, the preceding Ayat of Sura Nisa deals with prostitutes of the time. He believes these rulings were temporary and were abrogated later when a functioning state was established and society was ready for permanent rulings, which came in Sura Nur, Ayat 2 and 3, prescribing flogging as a punishment for adultery. He does not see stoning as a prescribed punishment, even for married men, and considers the Hadiths quoted supporting that view to be dealing with either rape or prostitution, where the strictest punishment under Islam for spreading "fasad fil ardh", meaning corruption in the land, referring to egregious acts of defiance to the rule of law was carried out.[citation needed]

The Hadiths consider homosexuality as zina,[7] and male homosexuality to be punished with death.[42] For example, Abu Dawud states,[38][not specific enough to verify][43][page needed]

From Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, the Prophet (p.b.u.h) states that: "If a woman comes upon a woman, they are both adulteresses, if a man comes upon a man, then they are both adulterers.”

— Al-Tabarani in al-Mu‘jam al-Awat: 4157, Al-Bayhaqi, Su‘ab al-Iman: 5075

Narrated Abdullah ibn Abbas: The Prophet said: If you find anyone doing as Lot's people did,[44] kill the one who does it, and the one to whom it is done.

— 38:4447

Narrated Abdullah ibn Abbas: If a man who is not married is seized committing sodomy, he will be stoned to death.

— 38:4448

The discourse on homosexuality in Islam is primarily concerned with activities between men. There are, however, a few hadith mentioning homosexual behavior in women;[45][46] The jurists are agreed that "there is no hadd punishment for lesbianism, because it is not zina. Rather a ta’zeer punishment must be imposed, because it is a sin..'".[47] Although punishment for lesbianism is rarely mentioned in the histories, al-Tabari records an example of the casual execution of a pair of lesbian slavegirls in the harem of al-Hadi, in a collection of highly critical anecdotes pertaining to that Caliph's actions as ruler.[48] Some jurists viewed sexual intercourse as possible only for an individual who possesses a phallus;[49] hence those definitions of sexual intercourse that rely on the entry of as little of the corona of the phallus into a partner's orifice.[49] Since women do not possess a phallus and cannot have intercourse with one another, they are, in this interpretation, physically incapable of committing zinā.[49]

Sodomy

Muslim scholars justify the prohibition of sodomy, anal sex (liwat) and oral sex, on the basis of the Qur'anic verse 2:223, saying that it commands intercourse only in the vagina (i.e. potentially procreational intercourse). The vaginal intercourse may be in any manner the couple wishes, that is, from behind or from the front, sitting or with the wife lying on her back or on her side.

There are also several hadith which prohibit sodomy.

Do not have anal sex with women.

— Reported by Ahmad, At-Tirmidhi, An-Nasa'i, and Ibn Majah

Muhammad also said, "Cursed he. ..who has sex with a woman through her back passage."

— Ahmad

Khuzaymah Ibn Thabit also reported that the Messenger of Allah said: "Allah is not too shy to tell you the truth: Do not have sex with your wives in the anus."

— Reported by Ahmad, 5/213

Ibn Abbas narrated: "The Messenger of Allah said: "Allah will not look at a man who has anal sex with his wife."

— Reported by Ibn Abi Shaybah, 3/529; At-Tirmidhi classified it as an authentic hadith, 1165

It is reported that `Umar Ibn Al-Khattab came one day to Muhammad and said, "O Messenger of Allah, I am ruined!" "What has ruined you?" asked the Prophet. He replied, "Last night I turned my wife over," meaning that he had had vaginal intercourse with her from the back. The Prophet did not say anything to him until the verse cited above was revealed. Then he told him, "[Make love with your wife] from the front or the back, but avoid the anus and intercourse during menstruation."

— (Reported by Ahmad and At-Tirmidhi)[50]

Furthermore, it is reported that Muhammad referred to anal sex as "minor incest".

Islamic law establishes two categories of legal, sexual relationships: between husband and wife, and between a man and his concubine. All other sexual relationships are considered zināʾ (fornication), including adultery and homosexuality, according to Islamic law and exegesis of the Qur'an. From the story of Lot it is clear that the Qur'an regards sodomy as an egregious sin. The death by stoning for people of Sodom and Gomorrah is similar to the stoning punishment stipulated for illegal heterosexual sex. There is no punishment for a man who sodomizes a woman because it is not tied to procreation. However, other jurists insist that any act of lust in which the result is the injecting of semen into another person constitutes sexual intercourse.[51]

In Islam, oral sex between a husband and a wife is considered "Makruh Tahrimi"[52] or highly undesirable by some Islamic jurists when the act is defined as the mouth and the tongue coming in contact with the genitals.[53][54] The reason behind considering this act as not recommended is manifold, the foremost being the issues of modesty, purification (Taharat) and cleanliness.[55]

The most common argument states[54] that the mouth and tongue are used for the recitation of the Qur'an and for the remembrance of Allah (Dhikr).[56] Firstly, scholars consider touching genitals by mouth as discouraged mentioning the reason that, touching genitals by the right hand rather than the left hand has been prohibited by Muhammad; as in their opinion, the mouth is comparatively more honorable than the right hand, for that touching genitals with the mouth is more abhorrent and vacatably excluded. Secondly, the status of genital secretions is debated among the four Sunni schools, some scholars viewing it as impure and others not.

Currently, sodomy is punishable by death in a number of Muslim countries, including Saudi Arabia and Yemen, as well as in Nigeria's Sharia courts.[49]

Incest

Hadith forbids incestous relationship (zinā bi'l-mahārim), sexual intercourse between someone who is mahram and prescribes execution as punishment.[8][9]

Narrated Ibn 'Abbas: That the Prophet said: "If a man says to another man: 'O you Jew' then beat him twenty times. If he says: 'O you effeminate' then beat him twenty times. And whoever has relations with someone that is a Mahram (family member or blood relative) then kill him."

Masturbation

Islamic scripture does not specifically mention masturbation. There are a few Hadiths mentioning it, but these are classified as unreliable.[57]

Bestiality

According to hadith, bestiality is defined under zina and its punishment is execution of the accused man or woman along with the animal.[2][10]

Narrated Ibn 'Abbas: That the Messenger of Allah said: "Whomever you see having relations with an animal then kill him and kill animal." So it was said to Ibn 'Abbas: "What is the case of the animal?" He said: "I did not hear anything from the Messenger of Allah about this, but I see that the Messenger of Allah disliked eating its meat or using it, due to the fact that such a (heinous) thing has been done with that animal."

Inclusions of the zināʾ definition

Zināʾ encompasses any sexual intercourse except that between husband and wife or between a master and his slave woman. It includes both extramarital sex and premarital sex, and is often translated as "fornication" in English.[58]

Technically, zināʾ only refers to the act of penetration, while non-penetrative sex acts outside of marriage were censured by the Prophet as that which can lead to zināʾ.[11][59]

According to sharia, the punishment for zināʿ varies according to whether the offender is "muhsan" (adult, free, Muslim and married at least once) or not muhsan (i.e. a minor, a slave, a non-Muslim or never married). A person only qualifies as muhsan if he or she meets all of the criteria. The punishment for an offender who is muhsan is stoning to death (rajm); the punishment for an offender who is not muhsan is 100 lashes. [60]

Accusation process and punishment

Islamic law requires evidence before a man or a woman can be punished for zināʾ. These are:[58][page needed][28][61]

- A Muslim confesses to zina four separate times. However, if the confessor takes back his words before the punishment is enforced or during the punishment, he/she will be released and set free. The confessor is in fact encouraged to take back their confession.[62][63][64]

- Four free adult male Muslim witnesses of proven integrity. They must testify that they observed the couple engaged in unlawful sexual intercourse without any doubt or ambiguity. They are able to say that they saw their private parts meet "like the Kohl needle entering the Kohl bottle."[62]

- Unlike witnesses in most other circumstances, they are neither legally nor morally obliged to testify, and in fact legal texts state that it is morally better if they don't.

- If any of the witnesses take back their testimony before the actual punishment is enforced, then the punishment will be abandoned, and the witnesses will be punished for the crime of false accusation.[62]

- The witnesses must give their testimony at the earliest opportunity.[62]

- If the offense is punished by stoning to death, the witnesses must throw the stones.

If a pregnant woman confesses that her baby was born from an illegal relationship then she will be subject to conviction in the Islamic courts. In cases where there are no witnesses and no confession then the woman will not receive punishment just because of pregnancy. Women can fall pregnant without committing illegal sexual intercourse. A woman could be raped or coerced. In this case, she is a victim and not the perpetrator of a crime. Therefore, she cannot be punished or even accused of misconduct merely on the strength of her falling pregnant.[64][65][66]

The four witnesses requirement for zina is revealed by Quranic verses 24:11 through 24:13 and various hadiths.[67][68] The testimony of women and non-Muslims is not admitted in cases of zināʾ or in other hadd crimes.

Any witness to or victim of non-consensual sexual intercourse, who accuses a Muslim of zina, but fails to produce four adult, pious male eyewitnesses before a sharia court, commits the crime of false accusation (Qadhf, القذف), punishable with eighty lashes in public.[69][70]

These requirements made zina virtually impossible to prove in practice.[1] Hence, there are very few recorded examples of stoning for zina being legally carried out.[1][18] In the 623-year history of the Ottoman Empire, the best-documented and most well-known pre-modern Islamic legal system, there is only one recorded example of the stoning punishment being applied for zināʿ, when a Muslim woman and her Jewish lover were convicted of zināʿ in 1680 and sentenced to death, the woman by stoning and the man by beheading. This was a miscarriage of justice according to the standards of Islamic law: adequate evidence was not produced, and the correct penalty for non-Muslims was 100 lashes rather than death.[71]

Some schools of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) created the principle of shubha (doubt). According to this principle, if there is room for doubt in the perpetrator's mind about whether the sexual act was illegal, he or she should not receive the hadd penalty, but could receive a less severe punishment at the discretion of the judge.[28] Jurists had varying opinions on what counted as legitimate "doubt" for this purposes. A typical example is a man who has sex with his wife's or his son's slave. This is zināʾ - a man can lawfully have sex only with his own slave. But a man might plausibly believe that he had ownership rights over his wife's or his son's property, and so think that having sex with their slaves was legal. The Ḥanafī jurists of the Ottoman Empire applied the concept of doubt to exempt prostitution from the hadd penalty. Their rationale was that since legal sex is legitimized, in part, by payment (the dower paid by the husband to the wife upon marriage, or the purchase price of a slave), a man might plausibly believe that prostitution, which also involves a payment in return for sexual access, was legal.[72] It is important to note that this principle did not mean that such acts were treated as legal: they remained offenses, and could be punished, but they were not liable for the hadd penalty of 100 lashes or stoning.

Sunni practice

All Sunni schools of jurisprudence agree that zināʾ is to be punished with stoning to death if the offender is a free, adult, married or previously married Muslim (muhsan). Persons who are not muhsan (i.e. a slave, a minor, never married or non-Muslim) are punished for zināʾ with one hundred lashes in public.[43][page needed][73]

Maliki school of Islamic jurisprudence considers pregnancy as sufficient and automatic evidence, unless there is evidence of rape. Other Sunni schools of jurisprudence rely on early Islamic scholars that state that a fetus can "sleep and stop developing for 5 years in a womb", and thus a woman who was previously married but now divorced may not have committed zina even if she delivers a baby years after her divorce.[74] The also argue that the woman may have been forced or coerced (see section above, 'Accusation process and punishment').The position of modern Islamic scholars varies from country to country. For example, in Malaysia which officially follows the Shafi'i fiqh, Section 23(2) through 23(4) of the Syariah (Sharia) Criminal Offences (Federal Territories) Act 1997 state,[75]

Section 23(2) - Any woman who performs sexual intercourse with a man who is not her lawful husband shall be guilty of an offence and shall on conviction be liable to a fine not exceeding five thousand ringgit or to imprisonment for a term not exceeding three years or to whipping not exceeding six strokes or to any combination thereof.

Section 23(3) - The fact that a woman is pregnant out of wedlock as a result of sexual intercourse performed with her consent shall be prima facie evidence of the commission of an offence under subsection (2) by that woman.

Section 23(4) - For the purpose of subsection (3), any woman who gives birth to a fully developed child within a period of six qamariah months from the date of her marriage shall be deemed to have been pregnant out of wedlock.

— Islamic Laws of Malaysia[76]

Minimal proof for zināʾ is still the testimony of four male eyewitnesses, even in the case of homosexual intercourse.[citation needed]

Prosecution of extramarital pregnancy as zināʾ, as well as prosecution of rape victims for the crime of zina, have been the source of worldwide controversy in recent years.[77][78]

Shi'a practice

Again, minimal proof for zināʾ is the testimony of four male eyewitnesses. The Shi'is, however, also allow the testimony of women, if there is at least one male witness, testifying together with six women. All witnesses must have seen the act in its most intimate details, i.e. the penetration (like "a stick disappearing in a kohl container," as the fiqh books specify). If their testimonies do not satisfy the requirements, they can be sentenced to eighty lashes for unfounded accusation of fornication (kadhf). If the accused freely admits the offense, the confession must be repeated four times, just as in Sunni practice. Pregnancy of a single woman is also sufficient evidence of her having committed zina.[39][need quotation to verify]

Human rights controversy

The zināʾ and rape laws of countries under Sharia law are the subjects of a global human rights debate.[81][82]

Hundreds of women in Afghan jails are victims of rape or domestic violence.[78] This has been criticized as leading to "hundreds of incidents where a woman subjected to rape, or gang rape, was eventually accused of zināʾ" and incarcerated.[83]

In Pakistan, over 200,000 zina cases against women, under its Hudood laws, were under process at various levels in Pakistan's legal system in 2005.[77] In addition to thousands of women in prison awaiting trial for zina-related charges, there has been a severe reluctance to even report rape because the victim fears of being charged with zina.[84][not specific enough to verify]

Iran has prosecuted many cases of zina, and enforced public stoning to death of those accused between 2001 and 2010.[85][86]

Zina laws are one of many items of reform and secularization debate with respect to Islam.[87][88] In the early 20th century, under the influence of colonial era, many penal laws and criminal justice systems were reformed away from Sharia in Muslim-majority parts of the world. In contrast, in the second half of the 20th century, after respective independence, a number of governments including Pakistan, Morocco, Malaysia and Iran have reverted to Sharia with traditional interpretations of Islam's sacred texts. Zina and hudud laws have been re-enacted and enforced.[89]

Contemporary human right activists refer this as a new phase in the politics of gender in Islam, the battle between forces of traditionalism and modernism in the Muslim world, and the use of religious texts of Islam through state laws to sanction and practice gender-based violence.[90][91]

In contrast to human rights activists, Islamic scholars and Islamist political parties consider 'universal human rights' arguments as imposition of a non-Muslim culture on Muslim people, a disrespect of customary cultural practices and sexual codes that are central to Islam. Zina laws come under hudud – seen as crime against Allah; the Islamists refer to this pressure and proposals to reform zina and other laws as ‘contrary to Islam’. Attempts by international human rights to reform religious laws and codes of Islam has become the Islamist rallying platforms during political campaigns.[92][93]

In popular culture

- The Stoning of Soraya M. – A 2008 Persian-language American drama film adapted from French-Iranian journalist Freidoune Sahebjam's 1990 book La Femme Lapidée, regarding to a mistaken-punishment of a false zina accusation.

See also

- Islamic criminal jurisprudence

- Islamic family jurisprudence

- Islamic sexual jurisprudence

- Modesty in Islam

- Namus

- Nikah mut‘ah

- Nikah urfi

- Ma malakat aymanukum and sex

- Rajm

- Repentance in Islam

- Sex and the law

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Semerdjian, Elyse (2009). "Zinah". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195305135.001.0001. ISBN 9780195305135.

- ^ a b c d e Semerdjian, Elyse (2008). "Off the Straight Path": Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo. Syracuse University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780815651550. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b Khan, Shahnaz (2011). Zina, Transnational Feminism, and the Moral Regulation of Pakistani Women. UBC Press. p. 8. ISBN 9780774841184. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b Akande, Habeeb (2015). A Taste of Honey: Sexuality and Erotology in Islam. Rabaah Publishers. p. 145. ISBN 9780957484511.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Taylor & Francis. p. 646. ISBN 9780415966924.

- ^ a b Habib, Samar (2010). Islam and Homosexuality (1st ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 211. ISBN 9780313379031. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ a b Mohd Izwan bin Md Yusof; Muhd. Najib bin Abdul Kadir; Mazlan bin Ibrahim; Khader bin Ahmad; Murshidi bin Mohd Noor; Saiful Azhar bin Saadon. "Hadith Sahih on Behaviour of LGBT" (PDF). islam.gov.my. Government of Malaysia. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b Clarke, Morgan (2009). Islam and New Kinship: Reproductive Technology and the Shariah in Lebanon. Berghahn Books. p. 41. ISBN 9781845454326. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b Kamali, Mohammad Hashim (2019). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: A Fresh Interpretation. Oxford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 9780190910648. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ a b Ahmed, Syed (1999). Law relating to fornication (Zina) in the Islamic legal system: a comparative study. Andhra Legal Decisions. p. 3,71,142.

- ^ a b c Peters, R. (2012). "Zinā or Zināʾ". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_8168.

- ^ Kamali, Mohammad Hashim (2019). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: A Fresh Interpretation. Oxford University Press. p. 91. ISBN 9780190910648.

- ^ Zuhur, Sherifa; Cözümler, Kadının İnsan Hakları--Yeni; Ways, Women for Women's Human Rights New (2005). Gender, sexuality and the criminal laws in the Middle East and North Africa: a comparative study. WWHR - New Ways. p. 45. ISBN 9789759267728.

- ^ Kugle, Scott Siraj al-Haqq (2010). Homosexuality in Islam: Critical Reflection on Gay, Lesbian, and Transgender Muslims. Oneworld Publications. ISBN 9781780740287.

- ^ Peters, Rudolph (2006). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: Theory and Practice from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 53-55. ISBN 978-0521796705.

- ^ a b A. Quraishi (1999), Her honour: an Islamic critique of the rape provisions in Pakistan's ordinance on zina, Islamic studies, Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 403–431

- ^ Peters, Rudolph (2006). Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law: : Theory and Practice from the Sixteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0521796705.

- ^ a b c Semerdjian, Elyse (2013). "Zinah". The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref:oiso/9780199764464.001.0001. ISBN 9780199764464.

- ^ Vikør, Knut S. (2014). "Sharīʿah". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Gunnar J. Weimann (2010). Islamic Criminal Law in Northern Nigeria: Politics, Religion, Judicial Practice. Amsterdam University Press. p. 77. ISBN 9789056296551.

- ^ "Pakistan Toughens Laws on Rape and 'Honor Killings' of Women". The New York Times. Oct 6, 2016.

- ^ Reza Aslan (2004), "The Problem of Stoning in the Islamic Penal Code: An Argument for Reform", UCLA Journal of Islamic and Near East Law, Vol 3, No. 1, pp. 91–119

- ^ "How Islam Views Adultery". islamonline.net. Retrieved July 6, 2020.

- ^ Quran 17:32

- ^ Saalih al- Munajjid, Muhammad. "Ruling on the things that lead to zina – kissing, touching and being alone together". Islamqa.info. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Quran 24:2

- ^ Quran 24:4–5

- ^ a b c Z. Mir-Hosseini (2011), Criminalizing sexuality: zina laws as violence against women in Muslim contexts, SUR-Int'l Journal on Human Rights, 8(15), pp. 7–33

- ^ Ziba Mir-Hosseini (2001), Marriage on Trial: A Study of Islamic Family Law, ISBN 978-1860646089, pp. 140–223

- ^ Hina Azam (2012), Rape as a Variant of Fornication (Zina) in Islamic Law: An Examination of the Early Legal Reports, Journal of Law & Religion, Volume 28, 441–459

- ^ 2:23:413

- ^ Understanding Islamic Law By Raj Bhala, LexisNexis, May 24, 2011

- ^ Bouhdiba, Abdelwahab (1985). Sexuality in Islam. Saqi Books. p. 288. ISBN 9780863564932.

- ^ Khan, Muhammad Aftab (2006). Sex and Sexuality in Islam. The University of Michigan: Nashriyat. p. 764. ISBN 9789698983048.

- ^ Abiad, Nisrine (2008). Sharia, Muslim States and International Human Rights Treaty Obligations: A Comparative Study. p. 136.

- ^ "Bukhari, Book: 89 - Statements made under Coercion, Chapter 6: If a woman is compelled to commit illegal sexual intercourse against her will". sunnah.com. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b "Rape against Muslim Women". www.irfi.org. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ a b c d Stephen O. Murray and Will Roscoe (1997), Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature, ISBN 978-0814774687, New York University Press, pp. 88–94

- ^ a b c Camilla Adang (2003), Ibn Hazam on Homosexuality, Al Qantara, Vol. 25, No. 1, p. 531

- ^ Michaelson, Jay (2011). God Vs. Gay? The Religious Case for Equality. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 9780807001592.

- ^ Quran 4:16

- ^ "The punishment for homosexuality - islamqa.info". islamqa.info.

- ^ a b Mohamed S. El-Awa (1993), Punishment In Islamic Law, American Trust Publications, ISBN 978-0892591428

- ^ The sunnah and surah describe the Lot's people in context of homosexuality and sodomy such as any form of sex between a man and woman that does not involve penetration of man's penis in woman's vagina.

- ^ Al-Hurr al-Aamili. Wasā'il al-Shīʿa وسائل الشيعة [Things of the followers] (in Arabic). Hadith number 34467-34481.

- ^ Atighetchi, Dariusch (2007). Islamic bioethics problems and perspectives. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 149. ISBN 9781402049620. Retrieved 13 July 2017.

- ^ "The punishment for lesbianism - islamqa.info". www.islamqa.com.

- ^ Bosworth, C.E. (1989). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 30: The 'Abbasid Caliphate in Equilibrium: The Caliphates of Musa al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid A.D. 785–809/A.H. 169–193. SUNY Press. ISBN 9780887065644.

- ^ a b c d Omar, Sara. "The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Law". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ^ "Sex Technique". islamawareness.net. Archived from the original on 21 July 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ^ Suad, Joseph (2006). Encyclopedia of Women and Islamic Cultures. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

- ^ Shaik Ahmad Kutty. "Ask The Scholar: What is meant by makruh?". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ "Oral Sex in Islam". The Majlis. JamiatKZN, Central-Mosque.com. 14 June 2003. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ a b "Are partners allowed to lick each other's private parts?". Mawlana Saeed Ahmed Golaub. Moulana Ismail Desai. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- ^ Hajj Gibril. "Questions On Sexuality, Oral sex". Living Islam. GF Haddad. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ 'Alî Abd-ur-Rahmân al-Hudhaifî (4 May 2001). "Remembrance of Allaah". Islamic Network. Islamic Network. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- ^ Omar, Sara. "[Sexuality and Law]". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Archived from the original on 2 April 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ a b Kecia Ali (2006), Sexual Ethics and Islam, ISBN 978-1851684564, Chapter 4

- ^ "What's the Classical Definition of Zina?". UNDERSTANDING ISLAM. 2003-05-13. Retrieved 2017-10-10.

- ^ Rudolph Peters, Crime and Punishment in Islamic Law, Cambridge University Press, 2005 ISBN 9780511610677, ch. 2

- ^ 17:4194

- ^ a b c d "The Legal Penalty for Fornication - IslamQA". IslamQA. 2012-07-28. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ al-Ikhtiyar li ta'lil al-Mukhtar. pp. 2/311–316.

- ^ a b Sengupta, Somini (2003-09-26). "Facing Death for Adultery, Nigerian Woman Is Acquitted". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- ^ "Pregnancy not proof of fornication | IslamToday - English". en.islamtoday.net. Retrieved 2016-06-13.

- ^ Qudamah, Ibn. Al-Mughni.

- ^ Quran 24:13, Kerby Anderson (2007), Islam, Harvest House ISBN 978-0736921176, pp. 87–88

- ^ 36 19.17, 36 19.18, 41 1.7

- ^ J. Campo (2009), Encyclopedia of Islam, ISBN 978-0816054541, pp. 13–14

- ^ R. Mehdi (1997), The offence of rape in the Islamic law of Pakistan, Women Living under Muslim Laws: Dossier, 18, pp. 98–108

- ^ Marc Baer, "Death in the Hippodrome: Sexual Politics and Legal Culture in the Reign of Mehmed IV," Past & Present 210, 2011, pp. 61-91 doi:10.1093/pastj/gtq062

- ^ James E. Baldwin (2012), Prostitution, Islamic Law and Ottoman Societies, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 55, pp. 117–52

- ^ Kecia Ali, Marriage and Slavery in Early Islam. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- ^ JANSEN, W. (2000), Sleeping in the Womb: Protracted Pregnancies in the Maghreb, The Muslim World, n. 90, p. 218–237

- ^ Laws of Malaysia SYARIAH CRIMINAL OFFENCES (FEDERAL TERRITORIES) ACT 1997, Government of Malaysia

- ^ CEDAW and Malaysia Women's Aid Organization, United Nations Report (April 2012), page 83–85

- ^ a b Pakistan Human Rights Watch (2005)

- ^ a b Afghanistan - Moral Crimes Human Rights Watch (2012); Quote "Some women and girls have been convicted of zina, sex outside of marriage, after being raped or forced into prostitution. Zina is a crime under Afghan law, punishable by up to 15 years in prison."

- ^ Ziba Mir-Hosseini (2011), Criminalizing sexuality: zina laws as violence against women in Muslim contexts, SUR - Int'l Journal on Human Rights, 15, pp. 7–31

- ^ Haideh Moghissi (2005), Women and Islam: Part 4 Women, sexuality and sexual politics in Islamic cultures, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-32420-3

- ^ KUGLE (2003), Sexuality, diversity and ethics in the agenda of progressive Muslims, In: SAFI, O. (Ed.). Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, Oxford: Oneworld. pp. 190–234

- ^ LAU, M. (2007), Twenty-Five Years of Hudood Ordinances: A Review, Washington and Lee Law Review, n. 64, pp. 1291–1314

- ^ "National Commission on the status of women's report on Hudood Ordinance 1979". Archived from the original on 2007-12-29.

- ^ Rahat Imran (2005), Legal Injustices: The Zina Hudood Ordinance of Pakistan and Its Implications for Women, Journal of International Women's Studies, Vol. 7, Issue 2, pp. 78–100

- ^ BAGHI, E. (2007) The Bloodied Stone: Execution by Stoning International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran

- ^ End Executions by Stoning - An Appeal AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL, 15 Jan 2010

- ^ Rehman J. (2007), The sharia, Islamic family laws and international human rights law: Examining the theory and practice of polygamy and talaq, International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 21(1), pp. 108–127

- ^ SAFWAT (1982), Offences and Penalties in Islamic Law. Islamic Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 149–181

- ^ Weiss A. M. (2003), Interpreting Islam and women's rights implementing CEDAW in Pakistan, International Sociology, 18(3), pp. 581–601

- ^ KAMALI (1998), Punishment in Islamic Law: A Critique of the Hudud Bill of Kelantan Malaysia, Arab Law Quarterly, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 203–234

- ^ QURAISHI, A (1996), Her Honor: An Islamic Critique of the Rape Laws of Pakistan from a Woman-Sensitive Perspective, Michigan Journal of International Law, vol. 18, pp. 287–320

- ^ A. SAJOO (1999), Islam and Human Rights: Congruence or Dichotomy, Temple International and Comparative Law Journal, vol. 4, pp. 23–34

- ^ K. ALI (2003), Progressive Muslims and Islamic Jurisprudence: The Necessity for Critical Engagement with Marriage and Divorce Law, In: SAFI, O. (Ed.). Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism, Oxford: Oneworld, pp. 163–189

- DeLong-Bas, Natana J. (2004). Wahhabi Islam: From Revival and Reform to Global Jihad (First ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-516991-1.

Further reading

- Calder, Norman, Colin Imber, and R. Gleave. Islamic Jurisprudence in the Classical Era. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge UP, 2010.

- Johnson, Toni, and Lauren Vriens, "Islam: Governing Under Sharia.", Council on Foreign Relations. Council on Foreign Relations, Inc., 24 Oct. 2011. Web. 19 Nov. 2011.

- Karamah: Muslim Women Lawyers for Human Rights, "Zina, Rape, and Islamic Law: An Islamic Legal Analysis of the Rape Laws in Pakistan." 26 Nov. 2011.

- Khan, Shahnaz. "Locating The Feminist Voice: The Debate On The Zina Ordinance." Feminist Studies 30.3 (2004): 660–685. Academic Search Complete. Web. 28 Nov. 2011.

- McAuliffe, Jane Dammen. The Cambridge Companion to the Qurʼān. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UP, 2006

- Peters, R. "Zinā or Zināʾ (a.)." Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition. Edited by: P. Bearman;, Th. Bianquis;, C.E. Bosworth;, E. van Donzel; and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2011. Brill Online. UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT AUSTIN. 17 November 2011

- Peters, R. "The Islamization of criminal law: A comparative analysis", in WI, xxxiv (1994), 246–74.

- Quraishi, Asifa. "Islamic Legal Analysis of Zina Punishment of Bariya Ibrahim Magazu, Zamfara, Nigeria." Muslim Women's League. Muslim Women's League, 20 Jan. 2001

External links

- Zina prosecution in Katsina State, Northern Nigeria Proceedings and Judgments in the Amina Lawal Case (2002)

- Sharia Law

- False Accusation Under Islamic Law

- Articles and Opinions: American Muslims need to speak out against violations of Islamic Shariah law (Asma Society)

- Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary - Zina Chapter, p. 43, at Google Books, Hisham M. Ramadan

- Afghanistan: Surge in Women Jailed for ‘Moral Crimes’ Zina in Afghanistan, Human Rights Watch (May 21, 2013)

- Mukhtar Mai - history of a rape case, Pakistan, BBC News

- Fate of another royal found guilty of adultery Zina in Saudi Arabia, The Independent (2009), UK