Derry City F.C.

| Derry City FC crest | |||

| Full name | Derry City Football Club | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | The Candystripes | ||

| Founded | 1928 | ||

| Ground | Brandywell Stadium, Derry, Northern Ireland | ||

| Capacity | 7,700 (2,900 seats) | ||

| Chairman | |||

| Manager | |||

| League | FAI League of Ireland | ||

| 2006 | 2nd | ||

|

| |||

Derry City Football Club (Irish: Cumann Peile Chathair Dhoire, IPA: [kʊmən̪ˠ pɛlʲə xahəɾʲ ɣɛɾʲə]) are an Irish football club based in Derry, Northern Ireland. The club, however, play in the FAI Premier Division, the top tier of the Republic of Ireland's FAI League of Ireland, and are the only participating club from Northern Ireland. They play their home matches at the Brandywell Stadium and wear red and white in a vertically-striped pattern. Their nickname, the Candystripes, derives from their colours. Others refer to the club as the Red and White Army or abbreviate the name to Derry or City. John Hume is the club's president,[1] while Jim Roddy fills the role of chief executive.[2] Hugh McDaid is the current chairman who, with his board, has assigned the team's management to Pat Fenlon and his assistant, Anthony Gorman.[3]

The club, founded in 1928, once played in the Irish League — Northern Ireland's league — and won a league title in the 1964–65 season. The era came to an end in 1972 when they left the league after the Irish Football Association, having earlier banned the use of their ground due to security fears over the Troubles in the Brandywell area and demanded they play their "home" games outside of Derry and in Coleraine, requested they continue playing there despite the unsustainability of the arrangement and the fact that security forces had ruled the area around their home safe enough to re-stage football. After almost 13 years without senior football, they applied to and were welcomed by the Football Association of Ireland into the new First Division of the League of Ireland for the 1985–86 season. After winning the First Division title and achieving promotion to the Premier Division in 1987, the club have remained there since. The club went on to win a domestic treble in the 1988–89 season and won the Premier Division again in 1996–97. Since entering the League of Ireland, Derry share a local rivalry with Finn Harps and contest the Northwest Derby with them.

History

Founding and the Irish League era

Founded in 1928, Derry City decided against using the official title of the city — Londonderry — in their name. Nationalists refer to the city as "Derry", while unionists often term it "Londonderry".[4] At the time, however, the dispute was not as politicised as it is today. The founders decided not to use the name of the city's previous primary club, Derry Celtic, to be more inclusive to football fans in the city.[5][6] The club were granted entry into the Irish League in 1929 as a professional outfit and appointed Joe McCleery as their first manager.[5] The club approached the Londonderry Corporation for use of the municipal Brandywell Stadium, and so began an association between the club and ground which survives today.

The club's first significant success came in 1935 when they lifted the City Cup.[7] They repeated the feat in 1937, but did not win another major trophy until 1949, when they beat Glentoran to win their first Irish Cup.[8] They won the Irish Cup for a second time in 1954, beating Glentoran again,[9] and for a third time in 1964 — that year also winning the Gold Cup — despite the club's conversion to part-time status after the abolishment of the maximum wage in 1961. This led to the club's first ever European outing, in the 1964–65 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup, where they were beaten by Steaua Bucureşti 5–0 on aggregate.[10] The club won the 1964–65 Irish League and subsequently became the first Irish League team to win a European tie over two legs, beating FK Lyn 8–6 on aggregate in the 1965–66 European Cup.[11] Derry did not complete the next round, as the Irish Football Association (IFA) claimed their ground was not up to standard,[5] even though a game had been played there during the previous round. Derry suspected sectarian motives,[12] as they played in a mainly Catholic city and so were supported largely by nationalists. The IFA, Belfast-based, was a cultural focal point of Protestant Northern Ireland and would rather have been represented by a traditionally unionist team.[13][14] Relations between the club and IFA quickly deteriorated.[15]

Until the late 1960s most teams' journey to the Brandywell was of little consequence, but in 1969 the Civil Rights campaign against the province's government disintegrated into communal violence, ushering in 30 years of the Troubles.[16] Despite the social and political turmoil of the day, on the field Derry still managed to perform, reaching the Irish Cup final in 1971, though being beaten 3–0 by Distillery.[17] As the republican locality surrounding the Brandywell saw some of the worst violence, numerous unionist-supported clubs were reluctant to play there. The Royal Ulster Constabulary ruled that the zone was unsafe and Derry were forced to travel to the majority unionist town of Coleraine, over 30 miles away, to play their "home" games at the Showgrounds. This situation lasted from September 1971 until October 1972 when, faced with dwindling crowds (most Derry fans were unwilling to travel to Coleraine due to the political situation and the longer journey) and dire finances, the club formally requested permission to return to the Brandywell. Despite a new assessment by the security forces concluding that the Brandywell was no longer any more dangerous than any other league ground and a lifting of the security ban,[16] Derry's proposal fell by one vote at the hands of their fellow Irish League teams who remained unwilling to travel there. On Friday 13 October, 1972, Derry withdrew from the league devastated and feeling marginalised, while a united complex of victimisation and persecution developed within the nationalist community behind the club.[18][19] Continuing in senior football without a ground was seen as unsustainable. Resignation from the league was the only option open to the club as they were effectively forced out.[5]

The club lived on as a junior team during the 13-year long "wilderness years", playing in the local Saturday Morning League, and sought re-admission to the Irish League.[18] Each time, the club nominated the Brandywell as its chosen home-ground but the Irish League refused re-admission. Suspecting refusal was driven by sectarian motives,[12] and believing they would never gain re-admission, Derry turned their attentions elsewhere.[16]

Entry into the League of Ireland

Derry applied to join the reorganised Football League of Ireland (the Republic of Ireland's league) in 1985 with the Brandywell as their home. After discussions over the proposal's viability, Derry were admitted to the league's new First Division for 1985, joining as semi-professionals. The move required special dispensation from the IFA and FIFA.[5] As their stadium was situated in a staunchly republican area once known as "Free Derry", with a history of scepticism towards the Royal Ulster Constabulary in the local community,[16] Derry received special permission from UEFA to steward their own games, as the presence of the force was regarded as more likely to provoke trouble than help prevent it.[20] The policy continues today and although effective, has, along with the participation in the Republic's league, solidified Derry's identity as a nationalist club, alienating many original or potential Protestant supporters.[16]

Derry's first match in the new system was a 3–1 League Cup win over Home Farm of Dublin at the Brandywell on 8 September, 1985.[21] The return of senior football to Derry attracted large, enthusiastic crowds.[5] Later in the season, after turning professional with the arrival of Noel King as player-manager, they won the League of Ireland First Division Shield with a 6–1 aggregate victory over Longford Town.[22] The following year — 1987 — Derry won the First Division and promotion to the Premier Division,[23] staying there since. The club reached the 1988 FAI Cup final, but lost to Dundalk. The next season — 1988–89 — the club were forced to revert to semi-professional status but Jim McLaughlin's side managed to win a treble; the league, the League Cup and the FAI Cup. Qualifying for the 1989–90 European Cup, they met past winners, Benfica, in the First Round.[5]

Modern highs and lows

Since 1989, Derry have won the Premier Division once — in 1996–97 — but have been runners-up on three occasions. They added three more FAI Cups to their trophy-tally in 1995, 2002 and 2006 and were runners-up in 1994 and 1997. The League Cup has also brought glory.[24] Derry's League of Ireland path has not always been smooth though. The club was on the verge of bankruptcy due to an unpaid tax bill in 2000. A huge fund-raising effort was undertaken by local famous faces and the city's people to save the club from extinction.[25] Martin O'Neill, then manager of Celtic, announced he would bring his side to the Brandywell to help raise funds,[26] as John Hume, then a Member of the European Parliament for the local Foyle constituency, used his parliament contacts and powers of persuasion to convince former European Cup winners to visit the Brandywell for friendlies.[27] Manchester United,[28] Barcelona[29] and Real Madrid,[30] as well as Celtic, came with star-studded teams between then and 2003. The money brought through the turnstiles helped keep the club in operation, but only just, as on-field results worsened under Gavin Dykes.[31] In 2003, Derry nearly lost their Premier Division place after finishing ninth and having to contest a two-legged relegation-promotion play-off with local Donegal rivals, Finn Harps.[32] However, Derry won the game 2–1 on aggregate after extra-time in the Brandywell and remained in the top-flight, avoiding further financial disaster.[33]

Fortunes improved when team-captain, Peter Hutton, took a player-manager role in 2004 before Stephen Kenny's appointment.[34] The club became the first club in Ireland to be awarded a premier UEFA licence that year.[35] Aided by the club's re-introduction of full-time football, Kenny blossommed positive results and Derry regained form.[36] In 2005, the club finished second[37] and entered the 2006–07 UEFA Cup's preliminary rounds. They reached the First Round, amazing many by beating IFK Göteborg and Gretna,[15][38][39] and after a home draw with Paris Saint-Germain they went down 2–0 away.[40] Derry's 2005 League Cup victory had also seen the club qualify for the second ever cross-border Setanta Cup in 2006.[41] The creation of this tournament in 2005 was aided by the lessening of sectarian tensions on the island of Ireland as a whole due to the Northern Ireland peace process. For the first time since their withdrawal from the Irish League, Derry hosted competitive matches against Linfield and Glentoran — teams with largely unionist fanbases.[16]

Derry finished second in the league to Shelbourne on goal difference in 2006,[42] but went on to win the FAI Cup, beating St. Patrick's Athletic after coming back from being a goal down on three occasions to clinch the game 4–3 in extra time.[43] With Derry winning the League Cup earlier in the season in as equally dramatic fashion (the game went to penalties after Derry were reduced to nine men),[44] the claiming of the FAI Cup amounted to a cup double.[45] They qualified for the 2007 Setanta Cup, as well as the preliminary rounds of the 2007–08 UEFA Champions League.[46] As Derry were accepted into the new-look FAI Premier Division for 2007,[47] scoring the highest number of criteria points between the teams accepted, 830,[48] Pat Fenlon took over from the departed Kenny.[49]

Colours and crests

Derry City wore claret and blue jerseys with white shorts for their first season — 1929–30. The colours were identical to Aston Villa's, historically one of England's most successful clubs,[5] and lasted until 1932, when white jersies with black shorts were adopted.[5] This style was replaced by the now-traditional red and white "candystripes" with black shorts for the 1934–35 season. The style derived from Sheffield United, who wore the pattern and, specifically, Billy Gillespie,[5] a native of Donegal.[50] He played for Sheffield United from 1913 until 1932, captaining them to a 1925 FA Cup win. The club's most capped player with 25 for Ireland,[50] he was held in such high regard in his home country that when he left Sheffield United in 1932 to become Derry's manager, they changed their strip within two years in reverence to him and his time in Sheffield.[51]

Derry have worn red and white stripes since, except from 1956 to 1962, when the club's players wore amber and black.[5] The colours were associated with Wolverhampton Wanderers,[52] a major force in English football during the 1950s,[53] but were not as successful for Derry as they had been for Wolverhampton Wanderers and were dropped. Jerseys since 1962 have had "candystripes" of varying thickness. The kit features white socks — originally black socks were used and occasionally red if a clash with the opposition occurred. Similarly, white shorts were adopted for a spell in the early 1970s and for 1985.[51] They are still sometimes worn if a clash occurs. Away jerseys have varied in colour from white, to navy and green stripes, to yellow, to white and light-blue stripes, and to black.[54]

Derry have had various kit suppliers, including Adidas,[55] Avec,[56] Erreà, Fila, Le Coq Sportif,[57] Matchwinner,[56] O'Neills,[58] Spall and currently, Umbro.[59] Commercial sponsorhip logos to appear on the shirt's front have included Northlands,[59] Warwick Wallpapers,[60] Fruit of the Loom,[56] Smithwick's[57] and AssetCo. Logos to have appeared on the sleeve have included the Trinity Hotel,[61] Tigi Bed Head and Tigi Catwalk. For 2007, the logos of local media, Q102.9 and the Derry News, appear on the back of the shirt just below the neck, along with the logo of Meteor Electrical on the jersey's front.[62]

The club did not sport a crest on the club jersey throughout the Irish League years, nor for most of the first League of Ireland season. Instead, the coat of arms of the city appeared on club memorabilia such as scarves, hats and badges. The symbols on the arms are a skeleton, three-towered castle, red St. George's cross and sword. The sword and cross are devices of the City of London, and along with an Irish harp embedded within the cross, demonstrate the link between the two cities — the city's official name under UK law is Londonderry and the city itself was developed by the Honourable the Irish Society, a livery company of the City of London. The castle is thought to be an old local Norman keep built in 1305 by the de Burca clan.[63] The skeleton is believed to be that of a knight of the same clan who was starved to death in the castle dungeons in 1332.[64] This is accompanied by the Latin motto, "Vita, veritas, victoria", meaning "Life, truth, victory."

In April 1986 the club ran a competition in local schools to design a crest for them. The winning entry was designed by John Devlin, a St. Columb's College student, and was introduced on 5 May, 1986 as Derry hosted Nottingham Forest for a friendly. The crest depicted a simplified version of the city's Foyle Bridge, which had opened 18 months previously, the traditional red and white stripes of the jersey bordered by thin black lines, the year in which the club was founded and a football in the centre representing the club as a footballing entity. The name of the club appeared in Impact font.

With the novelty of the Foyle Bridge wearing off over time, the crest lasted until 15 July, 1997, when the current one was unveiled at Lansdowne Road with the meeting of Derry City and Celtic during a pre-season friendly tournament.[65] The modern crest also features a centred football, the year of founding and the club's name in a contemporary sans-serif font — Industria Solid. The famous red and white stripes are present along with a red mass of colour filling the left half of the crest, separated from the right by a white stripe. Known cultural landmarks or items associated with the city are absent from the minimalist design. The crests have always been positioned over the heart on the home jerseys. The current away jersey has the crest on its upper-centre.

Home ground

Derry City's home ground is the municipal Brandywell Stadium, situated south-west of the Bogside in the Brandywell area of Derry. It is often abbreviated to "the Brandywell" and is also a local greyhound racing venue, with an ovoid track encircling the pitch. The dimensions of the pitch measure 111 by 72 yards.[66] The legal owner is the Derry City Council which lets the ground to the club.[5] Due to health and safety regulations the stadium has a seating capacity of 2,900 for UEFA competitions, although it can accommodate 7,700 on a normal match-day, terraces included.[67] The curved cantilever all-seated "New Stand" was constructed in 1991, while development on the still-insufficient facilities is set to continue with the planned £12 million upgrade to an expandable 8,000 all-seater by 2010.[68]

Plans of Derry City's to purchase a pitch fell through after their formation due to the tight time-scale between their birth in 1928 and the season's beginning in 1929 and so the Londonderry Corporation (now the Derry City Council) was approached for the use of the Brandywell which had been used for football up until the end of the 19th century. They agreed and the club still operate under the constraints of the Honourable the Irish Society charter limitations which declare that the Brandywell must be available for the recreation of the community. In effect, the club do not have private ownership and, thus, cannot develop by their own accord with that discretion or whether to sell being left to the Derry City Council.[5][69]

Derry City's first game at the Brandywell was a 2–1 loss to Glentoran on 22 August, 1929.[5] In 1933, the purchase of Bond’s Field in the Waterside was mentioned, but it was thought to be too far away from the fanbase which had built up on the Cityside, especially in the Brandywell area. They also had first option on Derry Celtic’s old ground, Celtic Park, but hesitated on a final decision and the Gaelic Athletic Association bought it ten years later. They also decided against buying Meenan Park for £1,500.[5]

Because of Northern Ireland's volatile political situation during the Troubles and security fears for Protestants and those of the unionist tradition visiting the mainly nationalist city of Derry, the Brandywell has not always been the home ground of Derry City. In 1970 and 1971, Derry had to play their "home" ties against Linfield at Windsor Park in Belfast — the home-ground of Linfield. From September 1971 until October 1972 Derry were forced to play all their "home" games at the Showgrounds in mainly Protestant Coleraine, over 30 miles away, as police ruled the republican Brandywell area as too unsafe for visiting unionists. The Brandywell did not see senior football for another 13 years as the Irish Football League upheld a ban on the stadium and Derry decided to leave the league as a result.[16] Only greyhound meetings and junior football were held during this time.[12] Derry's admission to the League of Ireland in 1985 saw a return of senior games.

In popular and general culture

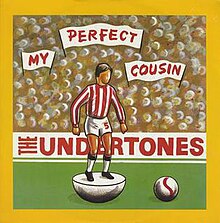

Derry City have made numerous appearances in popular and general culture. In the world of music, the club was given exposure by Derry punk band, the Undertones, who had the cover of their 1980 hit single, My Perfect Cousin, feature a Subbuteo figure sporting the colours of Derry City. The song's video saw the group's front-man, Feargal Sharkey, kick and leap to head a ball while wearing the red and white jersey.[70] Similarly, on the cover of their second ever single, Get Over You, the words "Derry City F.C." can be seen.[71]

The club has also featured on popular television. Due to the fact that they are a club based in Northern Ireland playing in the league of the Republic of Ireland they often receive the attention of broadcasters in both jurisdictions. In the BBC documentary series Who Do You Think You Are? shown the night before Derry's clash with Paris St. Germain in the 2006–07 UEFA Cup's First Round, it was highlighted that Archie McLeod, the grandfather of David Tennant, the tenth Doctor Who, was a Derry City player. Derry had supplied a lucrative signing-on fee and had enticed him over from the highlands of Scotland.[72] Likewise, features about the club were run by Football Focus prior to and after the same UEFA Cup game. Irish television has also featured the club. Derry City played in the first League of Ireland match ever to be shown live on television when they visited Tolka Park to play Shelbourne during the 1996–97 season. The game was broadcast on RTÉ's Network 2 and finished 1–1 with Gary Beckett scoring for Derry.

Another medium to play host to the club has been the radio. On 20 April, 2005, Derry City featured in an audio documentary The Blues and the Candy Stripes on RTÉ Radio 1's Documentary on One. The documentary was produced in the aftermath of the historic friendly game between Derry and Linfield that took place on 22 February, 2005 — the first between the two teams to occur since a game on 25 January, 1969 during which Linfield's fans had to be evacuated from the Brandywell by police at half-time due to civil unrest and ugly scenes within the ground.[73] The 2005 match was organised as somewhat of a security test in the run-up to the likely possibility that both teams, with socially polar fan-bases, would qualify for and be drawn against one another in a near-future Setanta Cup competition.[16]

Honours

- League titles: 4

- Irish Football League: 1964–65

- Football League of Ireland: 1988–89, 1996–97

- Football League of Ireland First Division: 1986–87

- FAI Cup: 4

- 1988–89, 1994–95, 2002, 2006[74]

- FAI League Cup: 7

- 1988–89, 1990–91, 1991–92, 1993–94, 1999–2000, 2005, 2006[75]

- IFA Cup: 3

- 1948–49, 1953–54, 1963–64

- League of Ireland First Division Shield: 1

- 1985–86

- City Cup: 2

- 1934–35, 1936–37

- Gold Cup: 1

- 1963–64

- Top Four Winners: 1

- 1965–66

- North-West Senior Cup: 14

- 1931–32, 1932–33, 1933–34, 1934–35, 1936–37, 1938–39, 1953–54, 1959–60, 1961–62, 1962–63, 1963–64, 1965–66, 1968–69, 1970–71

Records

Derry City's record appearer in League of Ireland football is Peter Hutton with 569 competitive appearances since the 1990–91 season.[76] Paul Curran has made the second highest number of appearances for the club in the League of Ireland with 518, followed by Sean Hargan with 403 since 1995.[77]

The club's all-time highest goal-scorer is Jimmy Kelly with 363 goals between 1930 and 1951.[78] Since the entry of the club into League of Ireland football, Liam Coyle is Derry's top scorer with 112 goals after 390 competitive appearances for the club between 1988 and 2003.[79] Derry's first ever scorer was Peter Burke at home to Glentoran on 22 August, 1929 as the club lost 2–1.[80] Two days later, Sammy Curran had the honour of scoring Derry's first hat-trick, as the club came back from 5–1 down away to Portadown, only to lose 6–5 to a late goal.[80] Barry McCreadie was Derry's first scorer in the League of Ireland as he scored during a 3–1 home win over Home Farm on 8 September, 1985.[80] Derry's first hat-trick in the League of Ireland was scored by Kevin Mahon away to Finn Harps on 15 December, 1985.[80] A number of capped internationals have also played for Derry.

Derry's record League of Ireland defeat was to Longford Town in January, 1986 — the score was 5–1.[62] The club's record League of Ireland win was 9–1 against Galway United in October, 1986.[62] The club has never been relegated in either the Irish League or the League of Ireland.[81] Derry are one of only two League of Ireland teams to have completed a treble. Derry's 5–1 away win against Gretna at Fir Park, Motherwell in the 2006–07 UEFA Cup's Second Qualifying Round is the largest away winning margin for any League of Ireland team in European competition. Derry played a record number of 54 games in the whole 2006 season, including all competitions. Previously, the record had been the 49 games played in all competitions during the treble-winning 1988-89 season.[82]

The Brandywell's record attendance in the League of Ireland system is 9,800 people who attended an FAI Cup Second Round tie between Derry and Finn Harps on 23 February, 1986.[66] In the Irish League, a crowd of 12,000 attended the 1929–30 season home game against Linfield.[83]

Supporters

By Irish standards, Derry City have a relatively large and deeply loyal fan-base. The club were considered among the strongest and best-supported teams in the Irish League,[81] and upon the club's entry into the League of Ireland in 1985, crowds of nearly 10,000 flocked to the Brandywell for the return of matches.[6] Derry's average home attendance of 3,127 was the highest of any team for the 2006 season.[84] The highest attendance was the last-night-of-the-season meeting between Derry and Cork City at the Brandywell on Friday 17 November when 6,080 watched Derry win 1–0.[85] Domestically, Derry's supporters travel to away games in "bus-loads".[60] They gave remarkable support in the club's 2006 UEFA Cup run — around 3,000 travelled to Motherwell and "maintained a wall of sound" as Derry beat Gretna 5–1 in Fir Park,[38][86] and over 2,000 went to Paris to see Derry play Paris Saint-Germain in the Parc des Princes.[87] During the home legs, ticketless fans desperate to see the games even hired double-decker buses to park outside the Brandywell and help them see over the ground's perimeter.[88][89]

Derry City F.C. has been the lynchpin in the life of the community in Derry since its foundation in 1928. Throughout the club's history, the Candystripes have provided a sporting outlet for young people and older supporters alike. The history of the club is intertwined with that of its city. It has seen struggle and marginalisation turn to renewal and success. The pride people have in this club reflects the pride we hold in our city. Derry City players and supporters alike are superb ambassadors for the city. Today, the club, like the city, looks to the future with great hope. For all its successes, Derry City would be nothing without the people of the city.

The club is known for its warm, community spirit and the supporters have played a pivotal role in the survival and successes of the club. When massive debts brought Derry close to extinction in the 2000–01 season, the local community responded en masse and saved the club. During the club's successful 2006 season, club captain, Peter Hutton said:

Nobody owns Derry City F.C. apart from the people of Derry. Five or six years ago the club was on its knees, on the verge of going out of business. There was no sugar-daddy, no millionaire, no Roman Abramovich to save the club. It was the people and the city who saved the club. People, fans, ordinary people; they went out and banged on doors to collect money, they went around pubs with collection buckets, they did what they could to keep the club alive. Derry is a close-knit place, a small community, they care about their club and that's why we still have a club. And every bit of success we may get this season is down to them.[91]

Support for the club is quite dependent on geography and crosses social boundaries. Fans come from both working class areas, such as the Brandywell area and Bogside, and more affluent regions of the city, like Culmore. The Cityside is seen as the traditional base of the club, especially the Brandywell area, although the Waterside is also home to a smaller number of supporters.[13] The club are supported mainly by Derry's nationalist community. The connection is rooted mainly in geography, as well as social, cultural and historical circumstances, as opposed to the club or its fans pushing towards the creation of a certain identity.[13] The club has a small minority of supporters of a Protestant upbringing. The city's Protestant community is largely apathetic, though some unionists and loyalists damn the club as a symbol of Catholicism and nationalism.[13][93] Joining the Republic of Ireland's league augmented the perception and, on occasion, Protestant hooligans have thrown missiles at Derry's supporter buses as they journeyed to or returned from games across the border.[94] Minor nationalist elements within the Derry City support-base see football as a means of reinforcing sectarian divides.[13]

With the city being a focal point of culture and activity serving the north-west region of Ireland, support stretches beyond the urban border and into the surrounding county; Limavady, Strabane in nearby County Tyrone[95] and areas of bordering County Donegal contain support.[96] The club has numerous supporter clubs, along with ultra fans, and support beyond Ireland — mainly emigrated city natives. Derry City Chat is a discussion website run by fans. Derry's fans share a rivalry with the supporters of Finn Harps and sing the Undertones' Teenage Kicks as a terrace anthem.[6]

First-team squad

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Managers

| Name | Nat. | From | To |

|---|---|---|---|

| Joe McCleery | 1929 | 1932 | |

| Billy Gillespie[97] | 1932 | 1940 | |

| Management Team Committee | 1940 | 1942 | |

| Willie Ross[97] | 1942 | 1953 | |

| Management Team Committee | 1953 | 1958 | |

| Tommy Houston[97] | 1958 | 1959 | |

| Matt Doherty | 1959 | 1961 | |

| Willie Ross | 1961 | 1968 | |

| Jimmy Hill[97] | 1968 | 1971 | |

| Doug Wood | 1971 | 1972 | |

| Willie Ross | 1972 | 1972 | |

| Jim Crossan | 1985 | 1985 | |

| Noel King[97] | 1985 | 1987 | |

| Jim McLaughlin | 1987 | 1991 | |

| Roy Coyle | 1991 | 1993 | |

| Tony O'Doherty | 1993 | 1994 | |

| Felix Healy | 1994 | 1998 | |

| Kevin Mahon | 1998 | 2003 | |

| Dermot Keely | 2003 | 2003 | |

| Gavin Dykes | 2003 | 2004 | |

| Peter Hutton[97] | 2004 | 2004 | |

| Stephen Kenny | 2004 | 2006 | |

| Pat Fenlon | 2006 | — |

Footnotes

- ^ Derry City Football Club - General Information. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Vive La Derry! Mayor congratulates Derry City on excellent performance", Derry City Council press release, 2006-09-15. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Gorman joins Fenlon backroom team", BBC Sport Online, 2006-12-31. Retrieved on 2007-01-01.

- ^ "City name row lands in High Court", BBC News, 2006-12-06. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Derry City FC - A Concise History. CityWeb, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c Collins, Conor. A History of Derry City. Albion Road, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Derry City FC - Honours List. CityWeb. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^ "The Great Cup Breakthrough", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Derry City's FAI Cup history. RTÉ Sport, 2006-11-29. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^ UEFA Cup Winners' Cup: Season 1964 - 65 preliminary round. UEFA.com, 2006-12-23. Retrieved on 2007-05-08.

- ^ "Derry City vs FK Lyn", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c Campbell, Denis. "My team - Derry City: An interview with Martin McGuinness", The Guardian, 2001-04-08. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e Cronin, Mike (2000). Template:PDFlink, International Sports Studies, De Montfort University, Leicester, England, vol. 21, no. 1 (2001), p. 25–38. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Burdsley, Daniel & Chappell, Robert. Soldiers, sashes and shamrocks: Football and social identity in Scotland and Northern Ireland, Sociology of Sport Online, Brunel University, UK. Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ^ a b Bradley, Steve. "Derry ponder a French Revolution", ESPNsoccernet, 2006-09-14. Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bradley, Steve. "Football's last great taboo?", ESPNsoccernet, 2005-02-22. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Northern Ireland - Cup Finals. The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b Mahon, Eddie (1998). Derry City. Guildhall Press. pp. p. 124.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Hassan, David (2002). Soccer and Society. Routledge. pp. vol. 3, no. 3, "People Apart: Soccer, Identity and Irish Nationalists in Northern Ireland", pp. 65–83. ISSN 1466-0970.

- ^ i) Football: Sectarianism. Eugene McMenamin MLA, Northern Ireland Assembly Reports, 2000-07-03. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) "PSNI help with UEFA Cup security", BBC Sport Online, 2006-09-22. Retrieved on2007-04-30. - ^ "Derry City 3 - 1 Home Farm", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Historic Shield Victory for City", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "First League Title in LOI", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Honours list. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Local band, the Undertones, played a benefit gig on 29 September, door-to-door collections took place around the city, while Phil Coulter, a local musician, hosted a golf classic on 27 September, 2000 to help raise moey. See: Proby, Johnny. "Derry City defeated Bohemians tonight in unusual circumstances", RTÉ.ie, 2000-09-07. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ i) "Payback time for O'Neill", BBC Sport Online, 2000-10-02. Retrieved on 2007-05-06.

ii) "O'Neill to bring Celtic to cash-strapped Derry", RTÉ.ie, 2000-09-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30. - ^ "City welcomes arrival of Barcelona team", Derry City Council press release, 2003-08-11. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Jackson, Lyle. "The belief of Derry", BBC Sport Online, 2002-10-28. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ i) "Busy Derry take on Barca", BBC Sport Online, 2003-08-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) "Barcelona treat Derry crowd", BBC Sport Online, 2003-08-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iii) The game against Barcelona is fondly remembered on the Brandywell terraces as the day fan-favourite, Liam Coyle, left the Catalan club's Carles Puyol "on his arse" as he utilised his trickery to beat the defender. See: Wilson, David (2007). Derry City FC: City Till I Die. Zero Seven Media. pp. p. 30. ISSN 1753-8904.{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ "The Real thing for Derry City", BBC Sport Online, 2001-07-25. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Gavin Dykes. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Finn Harps had finished second in the 2003 season's First Division.

- ^ i) Ramsay, Bartley & Dullaghan, Rodney. "Finn Harps Club History", FinnHarps.com, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii)The second leg of the fixture was Liam Coyle's last game for Derry before retiring. See: "Derry legend Coyle retires", BBC Sport Online, 2004-01-16. Retrieved on 2007-04-30. - ^ Peter Hutton. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ O'Neill-Cummins, Mark. "First Premier licence is awarded", RTÉ.ie, 2004-02-28. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Allen, Jeremiah. Ireland News, A2Z Soccer, 2007-03-01. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ eircom Premier League 2005. Soccerbot.com, 2005. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b Halliday, Stephen. "Slack Gretna given cruel lesson by five-star Derry", The Scotsman, 2006-08-11. Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ^ "Derry City to meet Paris St Germain in UEFA Cup", RTÉ Sport, 2006-08-25. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Jackson, Lyle. "PSG 2-0 Derry City (agg: 2-0)", BBC Sport Online, 2006-09-28. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Derry City FC - Setanta Sports Cup History. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ i) "Derry win but must settle for second", RTÉ Sport, 2006-11-17. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) Despite progress, on 10 November, 2006, Kenny announced he would leave Derry for Dunfermline Athletic at the end of the 2006 season to further his career. His success at Derry had raised eye-brows, especially in Scotland, after the club's 5–1 UEFA Cup demolition of Gretna there. He joined Dunfermline on 18 November — a day after Derry's last league game with Cork City at the Brandywell, which Derry won 1–0. See: "Kenny to leave Derry City at end of season", RTÉ.ie, 2006-11-10. Retrieved on 2006-12-04. - ^ i) "Derry triumph after Lansdowne Road drama", Irish Football Online, 2006-12-03. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) Technically, this was Kenny's last game at the helm for Derry as he returned from Dunfermline Athletic to perform an "advisory role". See: McIntosh, Mark. "Villa lost out in race for Kenny", Sunday Mirror, 2006-11-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iii) The match was the last football to take place at the old Lansdowne Road stadium. See: O'Hehir, Paul. "Derry edge a thriller", The Irish Times, 2006-12-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-16. - ^ i) "Jennings the hero as Derry retain League Cup", Irish Football Online, 2006-09-18. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) This was the club's second year in succession winning the League Cup. - ^ The 2006 cup wins could easily have concluded a second treble-winning season with the title-race being so close.

- ^ Derry City had initially qualified for the qualifying rounds of the 2007–08 UEFA Cup by way of their 2006 FAI Cup win but took their position in the 2007–08 UEFA Champions League after the 2006 League of Ireland champions, Shelbourne opted out of competing. They feared they would fail to be awarded a licence to compete because of their financial problems and were worried that their participation would prove detrimental to the UEFA coefficient of the league as they had to release their whole first-team prior to the 2007 season and form a team of mainly youngsters. See: "Shels opt out of Champions League", The Irish Times, 2007-03-30. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Membership of the 2007 FAI Premier Division was decided by fulfilling on-field and off-field criteria determined by the FAI's Independent Assessment Group other than just points attained during the previous season.

- ^ i) "How the teams rated in race for top flight", Irish Independent, 2006-12-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30. (Registration required.)

ii) Ireland 2006. The Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-04-30. - ^ i) "Fenlon is new Candystripes boss", BBC Sport Online, 2006-12-08. Retrieved on 2006-12-08.

ii) Fenlon's reign began with a 1–0 win in his first competitive game against Glentoran in the Setanta Cup on 26 February, 2007. See: Barrett, Deaglan. "Glentoran 0 - 1 Derry City: Late McHugh goal seals Setanta victory, CityWeb, 2007-02-26. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iii) After the initial victory, Derry performed poorly winning only two of their next nine matches. See: Results and Fixtures - 2007. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iv) By 17 April, 2007, the club had been knocked out of the 2007 Setanta Cup group stage, having recorded only one victory out of six games. See: "Drogheda Utd 2-1 Derry City: Defensive errors cost City again", CityWeb, 2007-04-27. Retrieved on 2007-04-30. - ^ a b Squad Profiles - Legends of the Game. Irish Football Association. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^ a b Colours and Jerseys. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Wolverhampton Wanderers. Historical Kits. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^ History of the English League championship. Yahoo! Sports, 2006-10-17. Retrieved on 2007-04-29.

- ^ Mahon (1998), p. 189.

- ^ Mahon (1998), p. 113.

- ^ a b c Mahon (1998), p. 156.

- ^ a b Mahon (1998), p. 7.

- ^ Mahon (1998), p. 109.

- ^ a b Mahon (1998), p. 49.

- ^ a b Mahon (1998), p. 67.

- ^ Mahon (1998), p. 197.

- ^ a b c "Derry City Football Club - General Information", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ Beattie, Sean (2004). Donegal. Sutton: Printing Press. ISBN 0-7509-3825-0.

- ^ i) History of Derry. Northern Ireland Tourist Board. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) Derry. International Civic Heraldry, 1996. Retrieved on 2007-05-06. - ^ Mahon (1998), pp. 189–192.

- ^ a b Derry City. What's the score?, 2000-01. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ i) "Brandywell gets seating increase", BBC Sport Online, 2006-08-09. Retrieved on 2006-10-03.

ii) Brandywell Stadium. The Stadium Guide. Retrieved on 2006-10-03. - ^ i) "Brandywell revamp plan unveiled", BBC Sport Online, 2006-06-15. Retrieved on 2006-10-01.

ii) "Big name to help City's bid for stadium", Belfast Telegraph, 2007-01-12. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iii) Duffy, Arthur. "There's only one show in town! - Insist Brandywell Properties Trust", Derry Journal, 2007-02-20. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

iv) Re-development of the Brandywell Stadium and Showgrounds: Executive Summary DOC (103 KiB). Brandywell Properties Trust Ltd. and Peter Quinn Consultancy Services Ltd., 2007. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

v) Re-development of the Brandywell Stadium and Showgrounds: Economic Appraisal ZIP (376 KiB). Brandywell Properties Trust Ltd. and Peter Quinn Consultancy Services Ltd., 2007. Retrieved on 2007-05-02. - ^ i) "Derry fans make stadium plea", Eleven-a-side.com, 2005-02-22. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

ii) Emerson, Steven. "Plans for new Brandywell stadium put on hold", Derry Journal, 2007-05-01. Retieved on 2007-05-01.

iii) Emerson, Steven. "Key questions on Brandywell plan remain unanswered", Derry Journal, 2007-05-01. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

iv) "Councillor views on Brandywell redevelopment", Derry Journal, 2007-05-01. Retrieved on 2007-05-02. - ^ Bradley, Michael. "The Undertones Connection", CityWeb, 1991-11-07. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Wilson (2007), p. 48.

- ^ Barratt, Dr. Nick. "Who do you think you are? (Third series): David Tennant", BBC History, 2006-09-27. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "The Blues and the Candy Stripes", RTÉ.ie, 2005-04-20. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Derry see off St Pat's in decider", BBC Sport Online, 2006-12-03. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ "Derry win eircom League Cup final", BBC Sport Online, 2006-09-18. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Dunleavy, Brian. Player Profiles - Peter Hutton. CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

- ^ i) Dunleavy, Brian (2006-11-17). "They must be enjoying the experience!", CityView, vol. 22, no. 27, p. 18.

ii) As of 20 May, 2007. - ^ Jimmy Kelly. Northern Ireland's Footballing Greats, 2007-01-20. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

- ^ Kelly, David. "Genius finally hangs up his boots", Irish Independent, 2004-01-21. Retrieved on 2007-05-04. (Registration required.)

- ^ a b c d "They were the First...", CityWeb, 2007. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

- ^ a b "Derry City dream on in Paris", FIFA.com, 2006-09-27. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Wilson, David (2007) City Till I Die. Zero Seven Media, p.50. ISSN 1753-8904.

- ^ Mahon (1998), p. 63.

- ^ eircom League AGM - Acting Director's Report. Foot.ie, 2006-12-10. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ^ "Derry's game with Cork best attended", Sunday Tribune, 2006-12-10. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

- ^ "Kenny elated after Derry triumph", BBC Sport Online, 2006-08-10. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Template:Fr icon Paris SG - Derry City / Coupe de l'UEFA 2006/2007. psg-fans-gretz, SkyRock, 2007-03-01. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ Carton, Donna. "Bus is just the ticket for fans", Sunday Mirror, 2006-09-03. Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ^ "Derry hordes cheer heroes into uncharted territory", Irish Independent, 2006-08-25. Retrieved on 2007-05-11. (Registration required.)

- ^ Mahon (1998). "Foreword" by Hume, John, p. 2.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Aidan. "Derry dare to dream", UEFA.com, 2006-09-15. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ The mural, with its domineering Celtic crest, demonstrates the somewhat idiosyncratic and extremely popular trend on the whole island of Ireland which sees the majority of Irish football fans primarily support club teams from Scotland, or even England, ahead of teams from their own national league. This has had a crippling effect on the development of the League of Ireland. For further information on this, see: Whelan, Daire (2006). Who Stole Our Game?: The Fall and Fall of Irish Soccer. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717140046.

- ^ For a more in-depth analysis and study of sectarian divisions and the politico-religious alignment of certain communities of fans to certain clubs within domestic Irish (especially Northern Irish) football, see: Cronin, Mike (1999). Sport and Nationalism in Ireland: Gaelic Games, Soccer and Irish Identity Since 1884. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1851824564.; Cronin, Mike & Mayall, David (1998). Sporting Nationalisms: Identity, Ethnicity, Immigration, and Assimilation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0714644493.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Dunn, Seamus (1995). Facets of the Conflict in Northern Ireland. Macmillan Press. ISBN 0312122802.; Armstrong, Gary & Giulianotti, Richard (1999). Football Cultures and Identities. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. "The Territorial Politics of Soccer in Northern Ireland" by Bairner, Alan & Shirlow, Peter. ISBN 978-0333730096.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Reilly, Thomas, Lees, Adrian, Davids, K. & Murphy W.J. (1988). Science and Football. E. & F.N. Spon. pp. "Sectarianism and Soccer Hooliganism in Northern Ireland" by Bairner, Alan & Sugden, John, pp. 572–578.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Tomlinson, Alan & Whannel, Garry (1986). Off the Ball. Longwood. pp. "Observe the Sons of Ulster: Football and Politics in Northern Ireland" by Bairner, Alan & Sugden, John, pp. 146–157. ISBN 9780745301228.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sugden, John & Bairner, Alan (1995). Sport, Sectarianism and Society in a Divided Ireland. Leicester University Press. pp. p. 87. ISBN 978-0718500184.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Minutes of the Special Meeting of Council. Strabane District Council press release, 2006-10-03. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ^ Episode 3. iCandy, 2006-05. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f Acted as player-manager.

References

- Coyle, Liam (2002). Born to Play. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-0954241001.

- Curran, Frank (1986). The Derry City Story. Donegal Democrat.

- Mahon, Eddie (1998). Derry City. Guildhall Press.

- Platt, William Henry Walker (1986). A History of Derry City Football Club, 1929–72. Platt. ISBN 978-0950195322.

- Wilson, David (2007). Derry City FC: City Till I Die. Zero Seven Media. ISSN 1753-8904.

External links

Official site:

Supporter site and discussion forum:

Association, news and information sites:

Visual:

- Derry City fans performing the "Grecque" in the Parc des Princes, Paris on 28 September 2006, YouTube, 2006-10-05.

- Derry City fans during their club's FAI Cup semi-final tie away to Sligo Rovers on 29 October 2006, YouTube, 2006-11-02.

Template:Fb end Template:Fb start

Template:Fb end Template:Fb start Template:UEFA Cup 2006/07 Template:Fb end