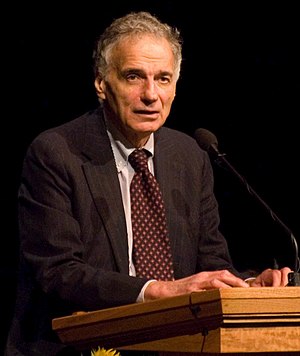

Ralph Nader

Ralph Nader | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 27, 1934 Winsted, Connecticut United States |

| Political party | Independent Green (affiliated non-member) Reform (affiliated non-member) |

| Height | 300px |

| Occupation | Attorney and Political Activist |

| Website | http://www.nader.org |

Ralph Nader (born February 27, 1934) is an American attorney and political activist in the areas of consumer rights, humanitarianism, environmentalism and democratic government. He helped found many governmental and non-governmental organizations, including the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Public Citizen, and several Public Interest Research Groups (PIRGs), including NYPIRG. Nader has been a staunch critic of corporations, which he believes wield too much power and are undermining the fundamental American values of democracy and human rights.

Nader ran for President in each of the 1992 to 2004 elections, most notably in the highly disputed 2000 election[1][2]. While he received no electoral votes, Nader was accused by opponents of George W. Bush of swinging the results of that election to the Republican Party.[3][4][5][6][7] Honored by Time magazine in 1999 as one of the most influential Americans of the 20th century, he appeared on the cover in 1969 as a consumer advocate for taking on the auto industry with the book Unsafe at Any Speed.[8][9][10]

Background and early career

Nader was born in Winsted, Connecticut. His parents, Nathra and Rose Nader, were Lebanese immigrants. Nathra Nader was employed in a textile mill, and at one point owned a bakery and restaurant where he engaged customers in political discourse.

Nader graduated from Princeton University in 1955 and Harvard Law School in 1958.[11] He served in the United States Army for six months in 1959, then began work as a lawyer in Hartford, Connecticut. Between 1961 and 1963, he was a Professor of History and Government at the University of Hartford. In 1964, Nader moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked for Assistant Secretary of Labor Daniel Patrick Moynihan. He also advised a United States Senate subcommittee on car safety. In the early 1980s, Nader spearheaded a powerful lobby against FDA approval of mass-scale experimentation of artificial lens implants. Nader also served as a faculty member at The American University Washington College of Law.

Recognition

In 1999 an NYU panel of eminent journalists ranked Nader's book Unsafe At Any Speed no. 38 among the top 100 pieces of journalism of the 20th century.[12] In 1990 Life Magazine,[13] and again in 1999 Time Magazine, [14][15] named Nader one of the 100 most influential Americans of the 20

| This is the talk page for discussing improvements to the Ralph Nader article. This is not a forum for general discussion of the article's subject. |

Article policies

|

Century. In its Dec 2006 article on the "100 most influential Americans" in history, in which its ten invited historians voted Nader 96

| This is the talk page for discussing improvements to the Ralph Nader article. This is not a forum for general discussion of the article's subject. |

Article policies

|

, The Atlantic Monthly stated: "He made the cars we drive safer; thirty years later, he made George W. Bush the president."[16]

Clash with the automobile industry

Nader's first consumer safety articles appeared in the Harvard Law Record, a student publication of Harvard Law School, but he first criticized the automobile industry in an article he wrote for The Nation in 1959 called "The Safe Car You Can't Buy."[17] In 1965, Nader wrote Unsafe at Any Speed, a study that purported to demonstrate that many American automobiles were unsafe, especially the Chevrolet Corvair manufactured by General Motors. The Corvair had been involved in numerous accidents involving spins and rollovers, and there were over 100 lawsuits pending against GM in connection to accidents involving the popular sports car. These lawsuits provided the initial material for Nader's investigations into the safety of the car[18] GM tried to discredit Nader, hiring private detectives to tap his phones and investigate his past, and hiring prostitutes to trap him in compromising situations.[19][20] GM failed to uncover any wrongdoing, and never explained resorting to smear tactics instead of defending the car in the popular press, where the company had considerable corporate influence. GM's avoidance of technical journals makes more sense, as it was well known among auto engineers that the Corvair's swing axle suspension handled miserably.[21][22] Upon learning of GM's actions, Nader successfully sued the company for invasion of privacy, forced it to publicly apologize, and used much of his $284,000 net settlement to expand his consumer rights efforts. Nader's lawsuit against GM was ultimately decided by the New York Court of Appeals, whose opinion in the case expanded tort law to cover "overzealous surveillance".[23]

Nader's advocacy of automobile safety and the publicity generated by the publication of Unsafe at Any Speed, along with concern over escalating nationwide traffic fatalities, led to the unanimous passage of the 1966 National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act. The Act established the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, and marked an historic shift in responsibility for automobile safety from the consumer to the manufacturer. The legislation mandated a series of safety features for automobiles, beginning with safety belts and stronger windshields.[24][25][26]

A 1972 National Highway Traffic Safety Administration safety commission report conducted by Texas A&M University concluded that the 1960-1963 Corvair possessed no greater potential for loss of control than its contemporaries in extreme situations.[27] A different account, however, was given in John DeLorean's "General Motors autobiography", On a Clear Day You Can See General Motors, 1979 (published under the name of his would-be ghostwriter, J. Patrick Wright), in which DeLorean asserts that Nader's criticisms were valid. The specific Corvair design flaws were corrected in the last years of the Corvair's production, although by then the Corvair name was irredeemably compromised.

Activism

Hundreds of young activists, inspired by Nader's work, came to DC to help him with other projects. They came to be known as "Nader's Raiders" who, under Nader, investigated government corruption, publishing dozens of books with their results:

- Nader's Raiders (Federal Trade Commission)

- Vanishing Air (National Air Pollution Control Administration)

- The Chemical Feast (Food and Drug Administration)

- The Interstate Commerce Omission (Interstate Commerce Commission)

- Old Age (nursing homes)

- The Water Lords (water pollution)

- Who Runs Congress? (Congress)

- Whistle Blowing (punishment of whistle blowers)

- The Big Boys (corporate executives)

- Collision Course (Federal Aviation Administration)

- No Contest (corporate lawyers)

- Destroy the Forest (Destruction of ecosystems worldwide)

- Operation: Nuclear (Making of a nuclear missile)

In 1971, Nader founded the non-governmental organization (NGO) Public Citizen as an umbrella organization for these projects. Today, Public Citizen has over 140,000 members and scores of researchers investigating Congressional, health, environmental, economic and other issues. Their work is credited with facilitating the passage of the Safe Drinking Water Act and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), and prompting the creation of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC).

In the 1970's and 1980's Nader was a key leader in the anti-nuclear power movement. "By 1976, consumer advocate Ralph Nader, who later became allied with the environmental movement 'stood as the titular head of opposition to nuclear energy'" [28] [29] He advocates the complete elimination of nuclear energy in favor of solar, tidal, wind and geothermal, citing environmental, worker safety, migrant labor, national security, disaster preparedness, foreign policy, government accountability and democratic governance issues to bolster his position. [30]

Non-profit organizations

In 1980, Nader resigned as director of Public Citizen to work on other projects, forcefully campaigning against what he believed to be the dangers of large multinational corporations. He went on to start a variety of non-profit organizations:

- Capitol Hill News Service

- Citizen Advocacy Center

- Citizens Utility Boards

- Congress Accountability Project

- Consumer Task Force For Automotive Issues

- Corporate Accountability Research Project

- Disability Rights Center

- Equal Justice Foundation

- Foundation for Taxpayers and Consumer Rights

- Georgia Legal Watch

- National Citizens' Coalition for Nursing Home Reform

- National Coalition for Universities in the Public Interest

- Pension Rights Center

- PROD (truck safety)

- Retired Professionals Action Group

- The Shafeek Nader Trust for the Community Interest

- 1969: Center for the Study of Responsive Law

- 1970s: Public Interest Research Groups

- 1970: Center for Auto Safety

- 1970: Connecticut Citizen Action Group

- 1971: Aviation Consumer Action Project

- 1972: Clean Water Action Project

- 1972: Center for Women's Policy Studies

- 1980: Multinational Monitor (magazine covering multinational corporations)

- 1982: Trial Lawyers for Public Justice

- 1982: Essential Information (encourage citizen activism and do investigative journalism)

- 1983: Telecommunications Research and Action Center

- 1983: National Coalition for Universities in the Public Interest

- 1989: Princeton Project 55 (alumni public service)

- 1993: Appleseed Foundation (local change)

- 1994: Resource Consumption Alliance (conserve trees)

- 1995: Center for Insurance Research

- 1995: Consumer Project on Technology

- 1997?: Government Purchasing Project (encourage the government to purchase safe and healthy products)

- 1998: Center for Justice and Democracy

- 1998: Organization for Competitive Markets

- 1998: American Antitrust Institute (ensure fair competition)

- 1999?: Arizona Center for Law in the Public Interest

- 1999?: Commercial Alert (protect family, community, and democracy from corporations)

- 2000: Congressional Accountability Project (fight corruption in Congress)

- 2001?: League of Fans (sports industry watchdog)

- 2001: Citizen Works (promote NGO cooperation, build grassroots support, and start new groups)

- 2001: Democracy Rising (hold rallies to educate and empower citizens)

Presidential campaigns

Controversy regarding the effect of third-party votes

- Main article: The "Election Spoiler" Controversy

In the 2000 presidential election in Florida, George W. Bush defeated Al Gore by 537 votes. Nader received 97,421 votes. Proponents of this argument claim that Nader pulled votes from Al Gore, and this tilted the election in Bush's favor. The claim is that this was Nader's "greatest impact" on the election. Nader himself, both in his book Crashing the Party, and on his website, states: "In the year 2000, exit polls reported that 25% of my voters would have voted for Bush, 38% would have voted for Gore and the rest would not have voted at all."[31] Assuming these poll numbers are correct, the 13% plurality would have given Gore a victory in Florida and the presidency.

Some of the counter-arguments are documented as follows. Assuming the hypothetical case that Nader had not been running, there is no guarantee that all of his votes would have necessarily gone to any one candidate. It is well known that Nader's policies differ in many ways from the democrats, and he has been known at times to be sharply critical of some of the policies and ethics of the democratic candidates and the democratic party in general. So to assume that all of Nader's votes would go to the leading democratic candidate, is a conclusion that is questioned by many voters and analysts. In terms of public opinion, voting theory and political science, the validity argument is highly controversial. Opponents also argue that it is a political "cheap shot" to cast Nader as a scapegoat, particularly if he is already viewed by many people as something of a "pariah". How can a candidate with 2.7% of the popular vote be 100% responsible for the outcome of the election?

One theory states that the focus of Nader's platform advocated long-term fundamental changes to government policy. The anti-Nader/Pro-Gore argument advocates that the short-term goals were a means to an end for the long-term goals; however Nader and his supporters viewed the long-term goals as more important than the short-term goals. By this theory, the controversy can be attributed to the untimely coincidence of these objectives, and the conflict of the differing agendas. Most voters can agree that both short-term and long-term goals are essential, and beyond the intense political controversy, voters face an intractable predicament when they're forced to choose between the two.

Presidential campaign history

- 1972

- "Draft Nader" effort had no ballot line to offer, nor did Nader authorize his name to appear on any ballot until 1992.

- 1990

- Nader considered launching a third party around issues of citizen empowerment and consumer rights. He suggested a serious third party could address needs such as campaign-finance reform, worker and whistle-blower rights, government-sanctioned watchdog groups to oversee banks and insurance agencies, and class-action lawsuit reforms.

- 1992

- Nader stood in as a write-in for "none of the above" in both the 1992 New Hampshire Democratic and Republican Primaries [32] and received 3,054 of the 170,333 Democrat votes and 3,258 of the 177,970 Republican votes cast.[33] He was also a write-in candidate in the 1992 Massachusetts Democratic Primary, where he appeared at the top of the ballot.

- 1996

- Nader was drafted as a candidate for President of the United States on the Green Party ticket during the 1996 presidential election. He was not formally nominated by the Green Party USA, which was, at the time, the largest national Green group; instead he was nominated independently by various state Green parties (in some areas, he appeared on the ballot as an independent).

- 2000

- Nader ran actively in 2000 as candidate of the Green Party, which had been formed in the wake of his 1996 campaign. That year, he received 2,883,105 votes for 2.74 percent of the popular vote,[34] missing the 5 percent needed to qualify the Green Party for federally distributed public funding in the next election, yet qualifying the Greens for ballot status in many new states. In October of 2000, at the largest Super Rally [35] of his campaign, in New York City's Madison Square Garden 15,000 people paid $20 each [36], to hear Nader say that Al Gore and George W. Bush were "Tweedledee and Tweedledum -they look and act the same, so it doesn't matter which you get". The campaign also had some prominent union help The California Nurses Association and the United Electrical Workers endorsed his candidacy and campaigned for him [37].

- Nader's votes in New Hampshire and Florida exceeded the difference in votes between Gore and Bush.[38] A New Hampshire exit poll indicated that Nader's presence in the race was not a factor in Bush's victory in that state.[39] Winning either state would have given Gore the presidency, and while critics claim this shows Nader tipped the election to Bush, Nader has called that claim "a mantra -- an assumption without data."[40] Michael Moore at first argued that Florida was so close that votes for any of seven other candidates could also have switched the results[41], but in 2004 joined the view that Nader had helped make Bush President.[42][43], Other Nader supporters argued that Gore was primarily responsible for his own loss. [44] But Eric Alterman, perhaps Nader's most persistent critic, has regarded such apologist arguments as beside the point: "One person in the world could have prevented Bush's election with his own words on the Election Day 2000." [45] Nation columnist Alexander Cockburn cited Gore's failure to win over progressive voters in Florida who chose Nader, and congratulated those voters: "Who would have thought the Sunshine State had that many progressives in it, with steel in their spine and the spunk to throw Eric Alterman's columns into the trash can?"[46] Nader's actual influence on the 2000 election is the subject of considerable discussion, and there is no consensus on Nader's impact on the outcome.[47][48][49][50][51]

- 2004

- Nader announced on December 24, 2003 that he would not seek the Green Party's nomination for president in 2004; however, he did not rule out running as an independent candidate. On February 22, 2004, Nader announced on NBC that he would indeed run for president as an independent, saying, "There's too much power and wealth in too few hands." His campaign ran on a platform consistent with the Green Party's positions on major issues, such as opposition to the war in Iraq. Due to concerns about a possible spoiler effect in 2000, many Democrats urged Nader to abandon his 2004 candidacy. The Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, Terry McAuliffe, argued that Nader had a "distinguished career, fighting for working families", and "would hate to see part of his legacy being that he got us eight years of George Bush." He received 463,653 votes for 0.38% of the popular vote.[52] Nader replied to this in filmed interviews for the 2007 documentary An Unreasonable Man, by pointing out that, "Voting for a candidate of one's choice is a Constitutional right, and the Democrats who are asking me not to run are, without question, seeking to deny the Constitutional rights of voters who are, by law, otherwise free to choose to vote for me." In this campaign Democrats accused Nader of having his bid funded by Republicans who wanted a repeat of his effect on the 2000 election.

- 2008

- In February 2007, Nader left the door open for another possible White House bid in 2008 and criticized Democratic front-runner Hillary Clinton as "a panderer and a flatterer." Asked on CNN's Late Edition news program if he would run in 2008, Nader replied, "It's really too early to say.... I'll consider it later in the year."[53] Asked during a radio appearance to describe the former First Lady, Nader said, "Flatters, panders, coasting, front-runner, looking for a coronation ... She has no political fortitude."[54] Some Greens have started a campaign to draft Nader as their party's 2008 presidential candidate.[55]

- In June 2007, Nader again hinted at a run. He said, "You know the two parties are still converging -- they don't even debate the military budget anymore. I really think there needs to be more competition from outside the two parties."[56] Nader participated in the Green Party Presidential Debates in San Francisco on January 13, 2008, though not as an announced candidate. On January 30, 2008, he formed an exploratory committee for another possible run at the presidency, telling CNN he would run again if he can raise the necessary funds.[57]

Personal finances

According to the mandatory financial disclosure report that he filed with the Federal Election Commission in 2000, he then owned more than $3 million worth of stocks and mutual fund shares; his single largest holding was more than $1 million worth of stock in Cisco Systems, Inc. He also held more than $2 million in two money market funds.[58] Nader has donated seed money for many of the over four dozen non-profit organizations he has founded.[59]

Works

Books

Nader has authored, co-authored and edited many books, which include:

- Citizen Power: A Mandate for Change by Mike Gravel, forward by Ralph Nader

- Unsafe at Any Speed. Grossman Publishers, 1965.

- Action for a Change (with Donald Ross, Brett English, and Joseph Highland). Penguin (Non-Classics); Rev. ed edition, 1973.

- Whistle-Blowing (with Peter J. Petkas and Kate Blackwell). Bantam Press, 1972.

- Corporate Power in America (with Mark Green)

- You and Your Pension (with Kate Blackwell)

- The Consumer and Corporate Accountability

- In Pursuit of Justice

- Corporate Power in America

- Ralph Nader Congress Project

- Ralph Nader Presents: A Citizen's Guide to Lobbying

- Verdicts on Lawyers

- Who's Poisoning America (with Ronald Brownstein and John Richard)

- The Big Boys (with William Taylor)

- Nader, Ralph. The Good Fight: Declare Your Independency and Close the Democracy Gap. Paperback ed. Harper Collins Pub., 2004.

- Nader, Ralph. Crashing the Party: Taking on the Corporate Government in an Age of Surrender. Paperback ed. St. Martin's Pr., 2002.

- Nader, Ralph. Cutting Corporate Welfare. Paperback ed. Open Media, 2000.

- Nader, Ralph, and Wesley J. Smith. No Contest: Corporate Lawyers and the Pervertion of Justice in America. Hardcover ed. Random House Pub. Group, 1996.

- Nader, Ralph, and Wesley J. Smith. Collision Course: the Truth About Airline Safety. 1st ed. McGraw-Hill Co., 1993.

- Nader, Ralph, and Clarence Ditlow. Lemon Book: Auto Rights. 3rd ed. Asphodel Pr., 1990.

- Nader, Ralph, and Wesley J. Smith. Winning the Insurance Game: the Complete Consumer's Guide to Saving Money. Hardcover ed. Knightsbridge Pub., 1990.

- Nader, Ralph, and John Abbotts. Menace of Atomic Energy. Paperback ed. Norton, W.W. & Co., Inc., 1979.

- Ralph Nader, Joel Seligman, and Mark Green. Taming the Giant Corporation. Paperback ed. Norton, W. W. & Co., Inc., 1977.

- Canada Firsts (with Nadia Milleron and Duff Conacher)

- The Frugal Shopper (with Wesley J. Smith. )

- Getting the Best from Your Doctor (with Wesley J. Smith. )

- Nader on Australia

- The Ralph Nader Reader. Seven Stories Press, 2000. ISBN 1-58322-057-7

- "It Happened in the Kitchen: Recipes for Food and Thought"

- "Why Women Pay More" (with Frances Cerra Whittelsley)

- "Children First! A Parent's Guide to Fighting Corporate Predators"

- "The Seventeen Traditions" Regan Books, 2007. ISBN 0061238279

Articles

- The "I" Word - Boston Globe - May 31, 2005 - Nader calls for the impeachment of President George W. Bush (with Kevin Zeese)

- Letter to Senate Judiciary Committee on Alito Nomination - Jan. 10, 2006

- Bush to Israel: 'Take your time destroying Lebanon' - The Arab American News - Aug. 2006

- Bill Moyers For President Nader on Bill Moyers running for President in 2008, October 28, 2006

Selected speeches and interviews

- Bolohan, Scott (2007-2-16). "Nader critiques political apathy, personal values: Interview with Ralph Nader". The DePaulia.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Chowkwanyun, Merlin (2004-12-16). "The Prescient Candidate Reflects: An Interview with Ralph Nader". Counterpunch.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Nader, Ralph (1992-01-15). "Ralph Nader speaking at Harvard Law School".

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Video and audio links

- Audio/Video Interview on Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman: Ralph Nader on Why He Might Run In 2008, the Iraq War & the New Documentary "An Unreasonable Man". He also looks back at his childhood and his new book "Seventeen Traditions." Film director Henriette Mantel joins us to talk about "An Unreasonable Man". February 5th, 2007

- Audio/Video Interview on Democracy Now! with Amy Goodman: Ralph Nader on Conservative Democrats, Corporate Power and the Middle East. Wednesday, November 8th, 2006

- Ubben Lecture at DePauw University, September 27, 2007

- Ralph Nader video appearances on C-SPAN in RealVideo - rec. April 9, 2000 to present - Retrieved June 6, 2005

- A Call to Civic Engagement, online video of speech given on August 18 2005 in Montreal.

- Ralph Nader speaks at the Reform Party Convention, 2004 - Provided by C-SPAN in

- Archived Audio of Ralph Nader Statement at the End of 2004 Campaign, from Democracy Now! November 3, 2004

- Archived Video of Ralph Nader - Howard Dean Debate on C-SPAN, July 9, 2004

- Archived Video of Nader / Camejo 2004 campaign kickoff rally in San Francisco, July 16, 2004

- Archived Audio of Nader / Camejo 2004 campaign kickoff rally in San Francisco, July 16, 2004

- John Bachir Film: Ralph Nader Interview, 2004

- Ralph Nader speaks at the Commonwealth Club video

RealVideo format.

- On Corporate & Government Responsibility Talk at UC Berkeley April 26, 2002

- Nader on Iraq CBC Broadcast 3 days into the invasion of Iraq.

- Nader on Ethics of Public Participation at Center for Ethics, Emory College

- Ralph Nader on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart

- Ralph Nader and Howard Dean debate the role of third political parties in America

Notes

- An Unreasonable Man (2006). An Unreasonable Man is a documentary film about Ralph Nader that appeared at the 2006 Sundance Film Festival.

- Burden, Barry C. (2005). Ralph Nader's Campaign Strategy in the 2000 U.S. Presidential Election 2005, American Politics Research 33:672-99.

- Ralph Nader: Up Close This film blends archival footage and scenes of Nader and his staff at work in Washington with interviews with Nader's family, friends and adversaries, as well as Nader himself. Written, directed and produced by Mark Litwak and Tiiu Lukk, 1990, color, 72 mins. Narration by Studs Terkel. Broadcast on PBS. Winner, Sinking Creek Film Festival; Best of Festival, Baltimore Int'l Film Festival; Silver Plaque, Chicago Int'l Film Festival, Silver Apple, National Educational Film & Video Festival.

- Bear, Greg, "Eon" - the novel includes a depiction of a future group called the "Naderites" who follow Ralph Nader's humanistic teachings.

- Martin, Justin. Nader: Crusader, Spoiler, Icon. Perseus Publishing, 2002. ISBN 0-7382-0563-X

References

- ^ James W. Ceaser and Andrew F. Busch. The Perfect Tie: The True Story of the 2000 Presidential Election. Lanham, MD, Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. 2001

- ^ Jamin B. Raskin. Overruling Democracy: The Supreme Court v. The American People. New York: Taylor and Francis Books, Inc., 2003.

- ^ Online NewsHour, Vote 2004 /Politics 101. Third Parties in the U.S. Political Process

- ^ CNN.com. Green Party: Nader mulling independent run. Dec. 23, 2003.

- ^ NOW with Bill Moyers. Politics & Economy. Election 2004.The Third Parties.

- ^ Green camp: Democrats turn on Nader in search of a scapegoat: Pundits split on man whose Florida votes led to chaos.

- ^ Duncan Campbell. Green camp: Democrats turn on Nader in search of a scapegoat: Pundits split on man whose Florida votes led to chaos. The Guardian (London). November 15, 2000.

- ^ December 12, 1969 Cover of Time magazine

- ^ The Lonely Hero: Never Kowtow

- ^ The U.S.'s Toughest Customer

- ^ Candidates / Ralph Nader 2004

- ^ Barringer, Felicity (1999-03-01). "MEDIA; Journalism's Greatest Hits: Two Lists of a Century's Top Stories". NY Times. p. 2.

- ^ Deparle, Jason (1990-09-21). "Washington at Work; Eclipsed in the Reagan Decade, Ralph Nader Again Feels Glare of the Public". NY Times.

- ^ "Ralph Nader". The American Program Bureau.

- ^ Kelly, James (2006-05-15). ""A Triumph of the Newsmagazine's Craft"". Time.com. Time Inc.

Nearly 100 Influentials were on hand that evening, including U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Ralph Nader, Will Smith, George Lucas, Nobel laureate James Watson, Bill Belichick and Dr. Andrew Weil.

- ^ "The Top 100: The Most Influential Figures in American History". Atlantic Monthly. 2006. p. 62.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Mickey Z. 50 American Revolutions You're Not Supposed To Know. New York: The Disinformation Company, 2005. p.87 ISBN 1932857184

- ^ Diana T. Kurylko. "Nader Damned Chevy's Corvair and Sparked a Safety Revolution." Automotive News (v.70, 1996).

- ^ Ralph Nader's museum of tort law will include relics from famous lawsuits—if it ever gets built December 2005

- ^ President Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Federal Role in Highway Safety: Epilogue -The Changing Federal Role May 7, 2005

- ^ Independent Suspensions: Swing axle suspension 1998

- ^ Original Triumph Spitfire -- Camber Compensator August 21, 1999

- ^ Nader v. General Motors Corp., 307 N.Y.S.2d 647 (N.Y. 1970).

- ^ Brent Fisse and John Braithwaite. The Impact of Publicity on Corporate Offenders. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1983.

- ^ Robert Barry Carson, Wade L. Thomas, Jason Hecht. Economic Issues Today: Alternative Approaches. M.E. Sharpe, 2005.

- ^ Stan Luger. Corporate Power, American Democracy, and the Automobile Industry. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ Brent Fisse and John Braithwaite, The Impact of Publicity on Corporate Offenders. State University of New York Press, 1983. p.30 ISBN 0873957334

- ^ Nuclear Power in an Age of Uncertainty (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, OTA-E-216, February 1984), p. 228, citing the following article:

- ^ Public Opposition to Nuclear Energy: Retrospect and Prospect, Roger E. Kasperson, Gerald Berk, David Pijawka, Alan B. Sharaf, James Wood, Science, Technology, & Human Values, Vol. 5, No. 31 (Spring, 1980), pp. 11-23

- ^ Frontline interview transcript

- ^ Dear Conservatives Upset With the Policies of the Bush Administration - Main Story Archive - Nader for President 2004 - www.votenader.org

- ^ THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: Write-In; In Nader's Campaign, White House Isn't the Goal February 18, 1992

- ^ 1992 PRESIDENTIAL PRIMARY

- ^ 2000 Presidential Election Results

- ^ Nader 'Super Rally' Draws 12,000 To Boston's FleetCenter

- ^ CNN.com - Loyal Nader fans pack Madison Square Garden - October 14, 2000

- ^ Nader, the Greens and 2008

- ^ 2000 Official Presidential General Election Results

- ^ Holly Ramer. Exit polls: Nader did not make difference for Bush in New Hampshire. The Associated Press, November 9, 2000.

- ^ Democrats Upset at 'Spoiler' in 2000 Race

- ^ http://www.michaelmoore.com/words/message/index.php?messageDate=2000-11-17 Blame Monica!

- ^ THE CONSTITUENCIES: LIBERALS; From Chicago '68 to Boston, The Left Comes Full Circle - New York Times

- ^ Convictions Intact, Nader Soldiers On - New York Times

- ^ S/R 25: Gore's Defeat: Don't Blame Nader (Marable)

- ^ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-alterman/ralph-nader-on-jon-stewar_b_40758.html?view=screen Ralph Nader on Jon Stewart

- ^ Alexander Cockburn. "The Best of All Possible Worlds." The Nation.November 9, 2000.

- ^ abstract of THE ROOTS OF THIRD PARTY VOTING The 2000 Nader Campaign in Historical Perspective. By: Allen, Neal; Brox, Brian J.. Party Politics, Sep2005, Vol. 11 Issue 5, p623-637, 15p, 3 charts

- ^ abstract of If it Weren't for Those ?*!&*@!* Nader Voters we Wouldn't Be in This Mess: The Social Determinants of the Nader Vote and the Constraints on Political Choice. By: Simmons, Solon J.; Simmons, James R.. New Political Science, Jun2006, Vol. 28 Issue 2, p229-244, 16p, 5 charts, 1 graph

- ^ Did Ralph Nader Spoil a Gore Presidency? A Ballot-Level Study of Green and Reform Party Voters in the 2000 Presidential Election

- ^ The Dynamics of Voter Decision Making Among Minor Party Supporters: The 2000 U.S. Presidential Election, British Journal of Political Science (2007), 37: 225-244

- ^ Minor Parties in the 2000 Presidential Election

- ^ 2004 Presidential Election Results

- ^ Nader Leaves '08 Door Open, Slams Hillary Reuters, February 5, 2007.

- ^ Ralph Nader: Hillary's Just a 'Bad Version of Bill Clinton' Feb. 16, 2007

- ^ DraftNader.org

- ^ Nader ponders run, calls Clinton 'coward'

- ^ Mooney, Alexander (2008-01-30). "Nader takes steps towards another White House bid". CNN Political Ticker. Cable News Network LP, LLLP.

- ^ [http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9502E3DC1531F93AA25755C0A9669C8B63 Nader Reports Big Portfolio In Technology

- ^ http://www.nader.org/ecm.html "Ralph Nader", Stephen Brobeck, Stephen; Mayer, Robert N; Herrmann, Robert O eds. (1997), Encyclopedia of the Consumer Movement, Santa Barbara, Calif., ABC-CLIO, 1997, Pp 383-388. (as posted on Ralph Nader's website Nader.org)

External links

- The Nader 2008 Presidential Exploratory Committee

- The Nader Page (not campaign-related)

- Nader/Camejo 2004

- Greens for Nader 2008 (a 2008 presidential draft site)

- Ballot access details

- 2004 Vote Profile: Ralph Nader

- Digital History Ralph Nader

- Interview with Ralph Nader for Princeton Report on Knowledge about the spin of information. April 26, 2007

- Ralph Nader on The Hour July 14, 2007

- 10 Things You Didn't Know About Ralph Nader March 23, 2007

- Articles needing cleanup from January 2008

- Wikipedia list cleanup from January 2008

- 1934 births

- Living people

- American activists

- American democracy activists

- American environmentalists

- American Maronites

- Anti-corporate activists

- Anti-nuclear power activists

- Consumer rights activists

- American political writers

- American non-fiction environmental writers

- Connecticut lawyers

- Social Progressives

- Lebanese Americans

- Maronites

- Catholics

- Green Party (United States) politicians

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Princeton University alumni

- United States presidential candidates