Macedonians (ethnic group)

| File:Maceds2.jpg | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 1.8 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 1, 297, 981[1] | |

| 83, 978[2] | |

| 74, 162[3] | |

| 61, 105[4] | |

| 60, 362[5] | |

| 42, 812[6] | |

| 37, 055[7] | |

| 31, 518[8] | |

| 25, 847[9] | |

| 13, 696[10] | |

| 5, 071[11] | |

| 4, 697[12] | |

| 4, 600[13] | |

| 4, 270[14] | |

| 3, 972[15] | |

| 3, 669[16] | |

| 3, 349[17] | |

| 2, 904[18] | |

| 2, 300[19] | |

| 2, 278[20] | |

| 1, 284[21] | |

| 825[22] | |

| 762[23] | |

| 731[24] | |

| Elsewhere | unknown |

| Languages | |

| Macedonian | |

| Religion | |

| predominantly Macedonian, Serbian, Muslim, Protestant, Eastern Orthodox and others | |

The Macedonians[25] ([Македонци, Makedonci] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help))– also referred to as Macedonian Slavs[26]– are a South Slavic people who are primarily associated with the Republic of Macedonia. They speak the Macedonian language, a South Slavic language. About three quarters of all ethnic Macedonians live in the Republic of Macedonia, although there are also communities in a number of other countries.

Origins

Anthropology

The ancestry of present-day Macedonians is mixed. Their linguistic and cultural origins stem from the 6th century when various Slavic tribes migrated to, and settled in, the region of Macedonia.

The official position of the Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts is that as a whole the modern Macedonian genotype developed as a result of the absorption by the advancing Slavs of the local peoples living in the Region of Macedonia prior to their coming (Illyrians, Thracians, Greeks, Romans, etc.). This position is backed by the findings of most ethnographers such as Vasil Kanchov,[27] Gustav Weigand,[28] and the anthropologist Carleton S. Coon, which state that the Slavs in 6th century actively assimilated other tribal peoples by absorbing part of the indigenous populations of the area, including Greeks, Thracians and Illyrians.[29][30] By absorbing parts of the peoples living there the Slavs also absorbed their culture, and in that amalgamation a people was gradually formed with perhaps predominantly Slavic ethnic elements, speaking a Slavonic language and with a Slavic-Byzantine culture[31].

Some early 20th century researchers as William Z. Ripley, Coon[32] and Bertil Lundman[33], mainly considering the language as an indicator, described the Slavic speakers in Macedonia as Bulgarians, and often placed the both populations in a common racial subgroup. Other authors, like H. N. Brailsford, described Slavic speakers from Macedonia as related both with Serbs and Bulgarians, but still having attributes of a separate people.[34]

Certain scholars like Russian Alexander F. Rittih have stated that Macedonians did not intermix with any of the Turkic tribes that raided eastern Balkan regions such as Moesia Inferior, Wallachia and Dobrudja (modern Bulgaria and Romania) from the tenth century onwards. Because of the nature of their geographic location, Macedonians only mixed with the indegenous Balkaners that lived in the Region of Macedonia, and not later invaders. This view, held prominently in Macedonia, makes the ancestry of Macedonians unique compared to their eastern neighbours.[35]

Genes

The Macedonian population is also of special interest for HLA anthropological study in the light of unanswered questions regarding its origin and relationship with other populations, especially the neighbouring Balkan peoples.[36] According to some researches, they are most related to the Greeks, Bulgarians, and Romanians[37][38], but according to others, Macedonians are closest to Croats and Czechs.[39][40]. Macedonians are genetically closely related to the other Slavic people (the frequency of the proposed Slavic Haplogroup R1a1, formerly Eu19 ranges to 35% in Macedonians.[41] They are sharply differentiated from their southern neighbours, the Greeks:

Similar cases of even more significant frequency change over a short geographic distance occur between the southern Slavic-speaking populations and their adjacent neighbors:...and Macedonians versus Greeks (30.0%; 95% CI 19.1%–43.8% vs.13.8%; 95% CI 10.1%–18.5%).[42]

They also share"the genetic contribution of the people who lived in the region before the Slavic expansion" [43]. It is also corroborated that there is some non-European, inflow in the modern Macedonians.[44]Furthermore, these genetic studies support the theories that Macedonians genetic heritage is derived from a mixture of ancient Balkan peoples, as well as the relatively newly arrived Slavs with deep European roots.

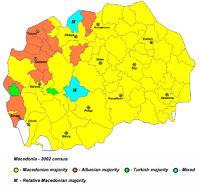

Population

The vast majority of Macedonians live along the valley of the river Vardar, the central region of the Republic of Macedonia and form about 64.18% of the population of the Republic of Macedonia (1,297,981 people according to the 2002 census). Smaller numbers live in eastern Albania, south-western Bulgaria, northern Greece, and southern Serbia, mostly abutting the border areas of the Republic of Macedonia. A large number of Macedonians have immigrated overseas to Australia, USA, Canada and in many European countries: Germany, the United Kingdom, Italy, and Austria, among others.

Macedonians abroad

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Macedonia (region) |

| Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

|

Subgroups and related groups |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

| Religion |

| Other topics |

Serbia

- see also: Macedonians in Serbia

Serbia recognizes the Macedonian minority on its territory as a distinct ethnic group and counts them in its annual census. 25,847 people declared themselves Macedonians in the 2002 census.

Bulgaria

- see also: Macedonians in Bulgaria

In the 2001 census in Bulgaria, 5,071 people declared themselves ethnic Macedonians (see the official data in Bulgarian here). Krassimir Kanev, chairman of the NGO Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, claimed 15,000 - 25,000 in 1998 (see here). In the same report Macedonian nationalists (Popov et al, 1989) claimed that 200,000 ethnic Macedonians live in Bulgaria. However, Bulgarian Helsinki Committee stated that the vast majority of the Slavic population in Pirin Macedonia has a Bulgarian national self-consciousness and a regional Macedonian identity similar to the Macedonian regional identity in Greek Macedonia (see here). Finally, according to personal evaluation of a leading local ethnic Macedonian political activist, Stoyko Stoykov, the present number of Bulgarian citizens with ethnic Macedonian self-consciousness is between 5,000 and 10,000 (source). (The Encarta Encyclopaedia states that Macedonians make up 2.5% of the total population, i.e. approximately 190,000, with no mention of how this figure is obtained, as it is evidently refuted by the latest census figures, see here.)

Macedonian groups in the country have reported official harassment (see Human rights in Bulgaria), with the Bulgarian Constitutional Court banning a small Macedonian political party in 2000 as separatist and Bulgarian local authorities banning political rallies. A political organization of the Macedonian minority in Bulgaria – UMO Ilinden-Pirin – claims that the minority has experienced a period of intensive assimilation and repression. It should be noted though that the Republic of Macedonia banned a similar pro-Bulgarian organization - Radko [1]- as separatist[2].

Albania

- see also: Macedonians in Albania

Albania recognizes ethnic Macedonians as an ethnic minority and delivers primary education in the Macedonian language in the border regions where most ethnic Macedonians live. In the 1989 census, 4,697[45] people declared themselves ethnic Macedonians.

Ethnic Macedonian organizations allege that the government undercounts their number and that they are politically under-represented - there are no ethnic Macedonians in the Albanian parliament. Some say that there has been disagreement among the Slav-speaking Albanian citizens about their being members of a Macedonian nation as a significant percentage of their number are Torbeš and self-identify as Albanians. External estimates on the population of ethnic Macedonians in Albania include 10,000 [3], whereas ethnic Macedonian sources have claimed that there are 120,000 - 350,000 ethnic Macedonians in Albania [4].

Greece

According to the latest Greek census held in 2001, there are 962 holders of citizenship of the Republic of Macedonia in Greece [5], although it should be noted that Greek census, like the censuses of some other EU member states (Italy, Spain, Denmark, France etc.), do not take into account the ethnicity of the inhabitants of the country and that immigration has significantly increased since then.

Claims regarding the existence of an ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece are rejected by the Greek government. These claims are directed at the Slavic-speaking community of northern Greece, which dominantly self-identifies as Greek (not as ethnic Macedonian) [6] and defines its language as Slavic or Dopia (a Greek word for 'local'). This community numbered by 41,017 people according to the latest Greek census to include a question on mother tongue held in 1951, and local authorities in Greece continue to acknowledge its existence. Depending on dialect, this language is classified by linguists as either Bulgarian or Macedonian. The size of this community today is estimated at between 100,000 and 200,000 by the Greek Helsinki Monitor, however, it also states that only an estimated 10,000-30,000 of these people might have an ethnic Macedonian national identity while the rest resent having their Hellenism questioned. GHM is basing this figure on the electoral performance of the ethnic Macedonian political party the region of Greek Macedonia: the Rainbow, which was founded around 1995 and received only 2,955 votes in Greek Macedonia in the 2004 elections [7]. In 2007, it did not stand for elections. The overwhelming majority of Greece's Slavic-speaking community is composed of people with Greek consciousness, which are pejoratively referred to with the term Grkomani by people in the Republic of Macedonia and trans-national ethnic Macedonian communities.[46] In 1993, at the height of the name controversy and just before joining the UN, the government in Skopje claimed that there were between 230,000 and 270,000 Macedonians living in northern Greece, while the Athens government claimed there were around 100,000 Greeks in the Republic of Macedonia.[8].

Other countries

Significant Macedonian communities can also be found in the traditional immigrant-receiving nations, as well as in Western European countries. It should be noted that census data in many European countries (such as Italy and Germany) does not take into account the ethnicity of émigrés from the Republic of Macedonia:

- Australia: The official number of Macedonians in Australia by birthplace or birthplace of parents is 82,000 (2001). The main Macedonian communities are found in Melbourne, Geelong, Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, Canberra and Perth. (The 2006 Australian Census included a question of 'ancestry' which, according to Members of the Australian-Macedonian Community, this will result in a 'significant' increase of 'ethnic Macedonians' in Australia. However, the 2006 census recorded 83,983 people of Macedonian (ethnic) ancestry.) See also Macedonian Australians;

- Canada: The Canadian census in 2001 records 31,265 individuals claimed wholly- or partly-Macedonian heritage in Canada (2001), although community spokesmen have claimed that there are actually 100,000-150,000 Macedonians in Canada [9] (see also Macedonian Canadians);

- USA: A significant Macedonian community can be found in the United States of America. The official number of Macedonians in the USA is 43,000 (2002). The Macedonian community is located mainly in Michigan, New York, Ohio, Indiana and New Jersey [10] (See also Macedonian Americans);

- Germany: There are an estimated 61,000 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Germany (2001);

- Italy: There are 74, 162 citizens of the Republic of Macedonia in Italy (Foreign Citizens in Italy).

- Switzerland: In 2006 the Swiss Government recorded 60,362 Macedonian Citizens living in Switzerland. [47]

Other significant ethnic Macedonian communities can also be found in the other Western European countries such as Austria, France, Switzerland, Netherlands, United Kingdom, etc.

Culture

The culture of the Macedonian people is characterized with both traditionalist and modernist attributes. It is strongly bound with their native land and the surrounding in which they live. The rich cultural heritage of the Macedonians is accented in the folklore, the picturesque traditional folk costumes, decorations and ornaments in city and village homes, the architecture, the monasteries and churches, iconostasis, wood-carving and so on.

Architecture

The typical Macedonian village house is presented as a construction with two floors, with a hard facade composed of large stones and a wide balcony on the second floor. In villages with predominantly agricultural economy, the first floor was often used as a storage for the harvest, while in some villages the first floor was used as a cattle-pen.

The stereotype for a traditional Macedonian city house is a two-floor building with white façade, with a forward extended second floor, and black wooden elements around the windows and on the edges.

Economy

In the past, the Macedonian population was predominantly involved with agriculture, with a very small portion of the people who were engaged in trade (mainly in the cities). But after the creation of the People’s Republic of Macedonia which started a social transformation based on Socialist principles, a middle and hard industry was being created.

Identities

- See also: Macedonian Question

Macedonians are people with a unique identity derived from an influence of different cultures. The large majority identify themselves as Orthodox Christians, who speak a Slavic language, and share similarities in culture with their Balkan neighbours.

Prior to the beginning of the Macedonian awakening

However, the concept of a distinct "Macedonian" ethnicity is seen as a relatively new arrival to the milieu of peoples that is the Balkans. The first records of people who called themselves Macedonians in ethnic connotation occurred in the late 19th century. Previously, any reference to "Macedonians" in medieval and early modern times tended to be used as a regional description rather than a distinct ethnic designation. Such examples include the Greek Macedonian dynasty which at one stage ruled the Byzantine Empire. References have also been made to Macedonian Slav rebellions against Byzantine rule,[48] but these have been interpreted by most scholars as non-specific, regional designations. The first ethnographic data pertaining to the Macedonian region as a whole emerged during Ottoman rule. These censuses lack any reference to a specific "Macedonian" ethnicity, but only records the population as either Greek or Bulgarian, as well as other minorities - Turks, Aromanians, Jews and Albanians.

Most of the ethnographers and travellers during Ottoman rule classified Slavic speaking people in Macedonia as Bulgarians. Examples include the 17th Century traveller Evliya Celebi in his Seyahatname - Book of Travels- and the Ottoman census of Hilmi Pasha in 1904 and later. However, they also remarked that the language spoken in Macedonia had somewhat of a distinctive character - often described as a "Western Bulgarian dialect". [11] Evidence also exists that certain Macedonian Slavs, particularly those in the northern regions, considered themselves as Serbs[12] and the Greek Idea predominated in southern Macedonia where it was supported by substantial part of the Slavic population. However, there were ethnographers like Jovan Cvijić and Alexander F. Rittih that qualified the Slavic-speaking population of Macedonia as a separate ethnicity.

The Macedonian Question

During Ottoman rule, most of the Christian population of Macedonia didn’t have a formed national identity. They identified themselves through religion. This was due to the millet system, which separated the population according to its religion, rather than ethnographic principles, and due to the strong Byzantine traditions of the Macedonian population until the mid 19th century, the Macedonians were a compact archaic Slavic mass, without a formed national identity.[49]

With the beginning of the Greek national renaissance, and after the creation of the modern Greek state, the Slavic-speaking people of Macedonia were considered as Greeks, because the Greek Patriarchy was given the exclusive right to manage the religious and political life of the Christians within the Ottoman Empire. [50]. After the beginning of the Bulgarian awakening, a lot of Macedonians saw it as a chance to struggle against the Greek religious dominance, and joined the process. Besides the existing Greek schools, new Bulgarian ones were being opened. Afterwards Serbia also started opening propagandist schools, and soon in the beginning of the 20th century, Macedonia became an arena in which Bulgarian, Greek and Serbian educational and church institutions were struggling for the assimilation of the local population. [51][52]

Knowing that the Ottoman Empire rather grouped people together along religious orientation,[53] those Macedonians that were under the jurisdiction of the Greek Patriarchate were considered Greeks, those under the Bulgarian Exarchate were considered Bulgarians, and those under Serbian Patriarchate as Serbs. After 1871 the majority of the Slav-speakers were under the influence of the Bulgarian Exarchate and its education system, thus in the early 20th century and beyond, were regarded as Bulgarians, whatever that meant.[54].[55][56][57] The term Bulgarian, within the context of Macedonian inhabitants, could have referring to any Slavic speaking Christian, regardless of specific ethnic orientation[58].

In general, national awakening in the Balkans developed later compared to Western Europe, developing last of all in Macedonia. By this time Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia had already declared themselves as autonomous sovereign Kingdoms. Continued Turkish oppression in Macedonia was coupled by polarising influences from Macedonia's neighbours. As each country vied to expand further, i.e. into Macedonia, they attempted to persuade the Macedonian population into allegiance. The forum of this persuasion was via provision of education and church services. During Ottoman rule, the Greeks became dominant within the Orthodox millet, however with the majority of Macedonians being illiterate, they were effectively insulated from Hellenization. Later, most Macedonians turned to the growing Bulgarian Exarchate and its education system due to the affinity of the languages compared to Greek.

Historical claims on Macedonia

Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia also claimed a historic right to Macedonia: Greece promoted the view that the modern Greeks were the closest living people to the ancient Macedonians, the original inhabitants of the southern (Greek) part of Macedonia- thus as their modern "successors", the Greeks believed Macedonia was rightfully Greek. The Bulgarians claimed Macedonia because it had been a vital part of the Bulgarian Empire and because according to the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 Macedonia was granted to the new Principality of Bulgaria. However, the Great Powers revised this treaty a few months later on the Congress of Berlin. Objectively, Bulgaria was closest linguistically and culturally to Macedonia. Likewise, Serbia evoked medieval legacy, whereby the Macedonian city of Skopje served as the capital of Stefan Dušan's 14th century Empire. The propaganda continued until the period between 1878 and 1912 when the rival propagandas succeeded in engaging the Slavic speaking population of Macedonia into three distinct parties, the pro-Serbian, the pro-Greek or the pro-Bulgarian one, at the expense of development of a unique Macedonian identity[59].

Macedonian awakening

The national awakening of the ethnic Macedonians gathered pace in the late 19th century and early 20th century - this is the time of the first expressions of ethnic nationalism by limited groups of intellectuals in Belgrade, Sofia, Istanbul, Thessaloniki and St. Petersburg. These individuals propagated the unique character of the Slavic speaking population of Macedonia, that is, that the Slavic-speakers of Macedonia compose a separate ethnicity which is different from Serbian and Bulgarian. The activities of these people was registered by Petko Slaveykov[60] and Stojan Novaković[61]

The first author that propagated the separate ethnicity of the Macedonians was Georgi Pulevski, who in 1875 published "Dictionary of Three languages: Macedonian, Albanian, Turkish", in which he wrote:

"What do we call a nation"? "People who are of the same origin and who speak the same words and who live and make friends of each other, who have the same customs and songs and entertainment are what we call a nation, and the place where that people lives is called the people's country. Thus the Macedonians also are a nation and the place which is theirs is called Macedonia."

In 1903 Krste Misirkov he published his book On Macedonian Matters in which he laid down the principles of the modern Macedonian nationhood and language. This book is considered by ethnic Macedonians as a milestone of the ethnic Macedonian identity and the apogee of the process of Macedonian awakening. In his article "Macedonian Nationalism" he wrote:

"I hope it will not be held against me that I, as a Macedonian, place the interests of my country before all... I am a Macedonian, I have a Macedonian's consciousness, and so I have my own Macedonian view of the past, present, and future of my country and of all the South Slavs; and so I should like them to consult us, the Macedonians, about all the questions concerning us and our neighbours, and not have everything end merely with agreements between Bulgaria and Serbia about us – but without us."

The next great figure of the Macedonian awakening was Dimitrija Čupovski, one of the founders of the of the Macedonian Literary Society, established in Saint Petersburg in 1902. In the period 1913-1918, Čupovski published the newspaper Македонскi Голосъ (Macedonian Voice) in which he and fellow members of the Petersburg Macedonian Colony propagated the existence of a Macedonian people separate from the Greeks, Bulgarians and Serbs, and sought to popularize the idea for an independent Macedonian state.

After the Balkan Wars, following division of the region of Macedonia amongst the Kingdom of Greece, the Kingdom of Bulgaria and the Kingdom of Serbia, and after World War I, the idea of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation was further spread among the Slavic-speaking population. The suffering during the wars, the endless struggle of the Balkan monarchies for dominance over the population increased the Macedonians' sentiment that the institutionalization of an independent Macedonian nation would put an end to their suffering. On the question of whether they were Serbs or Bulgarians, the people more often started answering: "Neither Bulgar, nor Serb... I am Macedonian only, and I'm sick of war."[62][63]

The first revolutionary organization that promoted the existence of a separate ethnic Macedonian nation was IMRO (United),[64] composed of former left-wing IMRO members. This idea was internationalized and backed by the Comintern which issued in 1934 a declaration supporting the development of the entity.[65] This action was attacked by the IMRO, but was supported by the Balkan communists. The Balkan communist parties supported the national consolidation of the ethnic Macedonian people and created Macedonian sections within the parties, headed by prominent IMRO (United) members. The sense of belonging to a separate Macedonian nation gained credence during World War II when ethnic Macedonian partisan detachments were formed, and especially after World War II when ethnic Macedonian institutions were created in the three parts of Macedonia,[66] including the establishment of the People's Republic of Macedonia within Socialist Yugoslavia.

History

The history of the ethnic Macedonians is closely associated with the historical and geographical region of Macedonia, and is manifested with their constant struggle for an independent state. After many decades of insurrections and living through several wars, the Macedonians in WWII managed to create their own country.

Symbols

|

|

- Sun: The official flag of the Republic of Macedonia, adopted in 1995, is a yellow sun with eight broadening rays extending to the edges of the red field.

- Coat of Arms: After independence in 1992, the Republic of Macedonia retained the coat of arms adopted in 1946 by the People's Assembly of the People's Republic of Macedonia on its second extraordinary session held on July 27, 1946, later on altered by article 8 of the Constitution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Macedonia. The coat-of-arms is composed by a double bent garland of ears of wheat, tobacco and poppy, tied by a ribbon with the embroidery of a traditional folk costume. In the center of such a circular room there are mountains, rivers, lakes and the sun; where the ears join there is a red five-pointed star, a traditional symbol of Communism. All this is said to represent "the richness of our country, our struggle, and our freedom".

Unofficial symbols

- Lion: The lion first appears in 1595 in the Korenich-Neorich coat of arms, where the coat of arms of Macedonia is included among with those of eleven other countries. On the coat of arms is a crown, inside a yellow crowned lion is depicted standing rampant, on a red background. On the bottom enclosed in a red and yellow border is written "Macedonia". Later versions of these coat of arms include a more detailed crown and lion with the word "Macedonia" written in a scroll like style. These coat of arms have also been adopted as the official emblem of VMRO-DPMNE, a Macedonian political party. Initially, it was adopted as a state symbol by Bulgaria.[citation needed]}

- Vergina Sun: (official flag, 1992-1995) The Vergina Sun is occasionally used to represent the Macedonian people by the diaspora through associations and cultural groups. The Vergina Sun is believed to have been associated with ancient Macedonian kings such as Alexander the Great and Philip II, although it was used as an ornamental design in Greek art long before the Macedonian period. The symbol was discovered in the Greek region of Macedonia and Greeks regard it as an exclusively Greek symbol, unrelated to Slavic cultures and it is copyrighted under WIPO as a State Emblem of Greece [13]. The Vergina sun on a red field was the first flag of the independent Republic of Macedonia, until it was removed from the state flag under an agreement reached between the Republic of Macedonia and Greece in September 1995.[67] Nevertheless, the Vergina sun is still used [14] unofficially as a national symbol by some groups in the country along with the new state flag.

See also

- Demographic history of Macedonia

- Bulgarians

- Serbs

- A list of prominent ethnic Macedonians

- Macedonian Canadians

- Macedonian Australians

- Macedonian Americans

- Ethnic Macedonians in Bulgaria

- Macedonians in Serbia

- Macedonians in Albania

- Ethnogenesis

- Macedonism

References

Further reading

- Brown, Keith, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Brunnbauer, Ulf (2004). "Fertility, families and ethnic conflict: Macedonians and Albanians in the Republic of Macedonia, 1944-2002". Nationalities Papers. 32 (3): 565–598.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|laysource=,|quotes=,|laysummary=, and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Cowan, Jane K. (ed.), Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference, Pluto Press, 2000. A collection of articles.

- Danforth, Loring M., The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-691-04356-6.

- Karakasidou, Anastasia N., Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood: Passages to Nationhood in Greek Macedonia, 1870-1990, University Of Chicago Press, 1997, ISBN 0-226-42494-4. Reviewed in Journal of Modern Greek Studies 18:2 (2000), p465.

- Mackridge, Peter, Eleni Yannakakis (eds.), Ourselves and Others: The Development of a Greek Macedonian Cultural Identity since 1912, Berg Publishers, 1997, ISBN 1-85973-138-4.

- Poulton, Hugh, Who Are the Macedonians?, Indiana University Press, 2nd ed., 2000. ISBN 0-253-21359-2.

- Roudometof, Victor, Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict: Greece, Bulgaria, and the Macedonian Question, Praeger Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-275-97648-3.

- Κωστόπουλος, Τάσος, Η απαγορευμένη γλώσσα: Η κρατική καταστολή των σλαβικών διαλέκτων στην ελληνική Μακεδονία σε όλη τη διάρκεια του 20ού αιώνα (εκδ. Μαύρη Λίστα, Αθήνα 2000). [Tasos Kostopoulos, The forbidden language: state suppression of the Slavic dialects in Greek Macedonia through the 20th century, Athens: Black List, 2000]

External links

- ^ 2002 census

- ^ 2006 Census

- ^ Foreign Citizens in Italy

- ^ 2004 est.

- ^ 2006 Census

- ^ 2002 Community Survey

- ^ 2006 census

- ^ 2001 census

- ^ 2002 census

- ^ 2001 census - Tabelle 13: Ausländer nach Staatsangehörigkeit (ausgewählte Staaten), Altersgruppen und Geschlecht - page 74

- ^ 2001 census

- ^ 1989 census

- ^ OECD Statistics

- ^ 2001 census

- ^ 2002 census

- ^ 2006 census

- ^ 2008 census

- ^ 2002 census

- ^ 2003 census

- ^ 2005 census

- ^ 2001 census

- ^ 2006 census

- ^ 2006 census

- ^ 2002 census

- ^ When the name Macedonians without any qualifiers is used to refer to ethnic Macedonians, it can be considered offensive by Greeks, especially those from Macedonia in northern Greece.

- ^ "Macedonian Slavs" can be translated into Macedonian as Македонски Словени (Makedonski Sloveni). "Slavs" is the primary qualifier used by scholars in order to disambiguate the ethnic Macedonians from all other Macedonians in the region (see Google scholar for instance). Krste Misirkov himself used the same qualifier numerous times in one of the first ethnic Macedonian patriotic texts "On Macedonian Matters" (most of the text in English here). The Slav Macedonians in Greece were happy to be acknowledged as "Slavomacedonians". A native of Greek Macedonia, a pioneer of Slav Macedonian schools in the region and a local historian, Pavlos Koufis, wrote in Laografika Florinas kai Kastorias (Folklore of Florina and Kastoria), Athens 1996, that (translation by User:Politis),

"[During its Panhellenic Meeting in September 1942, the KKE mentioned that it recognises the equality of the ethnic minorities in Greece] the KKE recognised that the Slavophone population was ethnic minority of Slavomacedonians]. This was a term, which the inhabitants of the region accepted with relief. [Because] Slavomacedonians = Slavs+Macedonians. The first section of the term determined their origin and classified them in the great family of the Slav peoples."

However, the current use of "Slavomacedonian" in reference to both the ethnic group and the language, although acceptable in the past, can be considered pejorative and offensive by some ethnic Macedonians living in Greece. The Greek Helsinki Monitor reports:

: "... the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness. Unfortunately, according to members of the community, this term was later used by the Greek authorities in a pejorative, discriminatory way; hence the reluctance if not hostility of modern-day Macedonians of Greece (i.e. people with a Macedonian national identity) to accept it." - ^ Пътуване по долините на Струма, Места и Брегалница. Битолско, Преспа и Охридско. Васил Кънчов (Избрани произведения. Том I. Издателство "Наука и изкуство", София 1970) [15]

- ^ (ETHNOGRAPHIE VON MAKEDONIEN, Geschichtlich-nationaler, spraechlich-statistischer Teil von Prof. Dr. Gustav Weigand, Leipzig, Friedrich Brandstetter, 1924, Превод Елена Пипилева)[16]

- ^ "Macedonia :: History. -- Encyclopaedia Britannica". Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ^ Coon, Carleton Stevens. The Races of Europe. Greenwood Press Reprint. ISBN 0-8371-6328-5., Chapter XII, section 15[17]

- ^ Macedonia and the Macedonian people. Blaze Ristovski.

- ^ in his book The Races Of Europe

- ^ Lundman, Bertil J. - The Races and Peoples of Europe (New York: IAAEE. 1977)[18]

- ^ http://www.promacedonia.org/en/hb/hb_4_10.html MACEDONIA: Its races and their future. H. N. Brailsford, London, 1906. p. 101]

- ^ Кто такие Македонцы? - Александр Ф. Риттих, Санкт-Петербург, 1914. (стр. 1, стр. 2)

- ^ Petlichkovski A, Efinska-Mladenovska O, Trajkov D, Arsov T, Strezova A, Spiroski M (2004). "High-resolution typing of HLA-DRB1 locus in the Macedonian population". Tissue Antigens. 64 (4): 486–91. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0039.2004.00273.x. PMID 15361127.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ivanova M, Rozemuller E, Tyufekchiev N, Michailova A, Tilanus M, Naumova E (2002). "HLA polymorphism in Bulgarians defined by high-resolution typing methods in comparison with other populations". Tissue Antigens. 60 (6): 496–504. PMID 12542743.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bulgarian Bone Marrow Donors Registry—past and future directions - Asen Zlatev, Milena Ivanova, Snejina Michailova, Anastasia Mihaylova and Elissaveta Naumova, Central Laboratory of Clinical Immunology, University Hospital "Alexandrovska", Sofia, Bulgaria, Published online: 2 June 2007 [19]

- ^ "European Journal of Human Genetics - Y chromosomal heritage of Croatian population and its island isolates".

- ^ Semino, Ornella (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective" (PDF). Science. 290: 1155–59. PMID 11073453.

- ^ Semino; et al. (2000), "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective" (PDF), Science, vol. 290, pp. 1155–59, PMID 11073453

{{citation}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe Siiri Rootsi et.al., American Journal of Human Genetics, 75, p.p. 128–137, 2004

- ^ Anthropological Evidence and the Fallmerayer Thesis

- ^ Tissue Antigens. Volume 55 Issue 1 Page 53-56, January 2000.HLA-DRB and DQB1 polymorphism in the Macedonian population.

- ^ Artan Hoxha and Alma Gurraj Local Self-Government and Decentralization: Case of Albania. History, Reforms and Challenges. In: Local Self Government and Decentralization in South - East Europe. Proceedings of the workshop held in Zagreb, Croatia 6 April 2001. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Zagreb Office, Zagreb 2001, pp 194-224 [20],

- ^ The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, (a) pg. 221 (b) pg. 51, by Loring M. Danforth, ISBN 0-691-04356-6

- ^ http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/fr/index/themen/01/07/blank/key/01/01.Document.20578.xls

- ^ The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. D P Hupchik

- ^ Балканско полуострво и јужнословенске земље. Јован Цвијић, Београд. (page 92-95)

- ^ Histoire de la Grèce moderne. Nikolaos Svoronos

- ^ За македонската нација. Драган Ташковски

- ^ "Shoot the Teacher!" Education and the Roots of the. Macedonian Struggle. Julian Allan Brooks.

- ^ The Balkans

- ^ (Brubaker 1996: 153; Ruhl 1916: 6; Perry in Lorrabee 1994: 61)

- ^ The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica. [21]

- ^ The Races and Religions of Macedonia, "National Geographic", Nov 1912. [22]

- ^ Carnegie Endowment for International peace.REPORT OF THE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION. To Inquire into the causes and Conduct OF THE BALKAN WARS, PUBLISHED BY THE ENDOWMENT WASHINGTON, D.C. 1914 [23]

- ^ The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World - Loring M. Danforth, ISBN13: 978-0-691-04356-2

- ^ Paul Fouracre. Cambridge Encyclopedia of Medieval History

- ^ "The Macedonian question" published 18 January 1871

- ^ Балканска питања и мање историјско-политичке белешке о Балканском полуострву 1886-1905. Стојан Новаковић, Београд, 1906.

- ^ Историја на македонската нација. Блаже Ристовски, 1999, Скопје.

- ^ "On the Monastir Road". Herbert Corey, National Geographic, May 1917 (page.388)

- ^ The Situation in Macedonia and the Tasks of IMRO (United) - published in the official newspaper of IMRO (United), "Македонско дело", N.185, April 1934

- ^ Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна - Февраль 1934 г, Москва

- ^ History of the Balkans, Vol. 2: Twentieth Century. Barbara Jelavich, 1983.

- ^ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""A Name for a Conflict or a Conflict for a Name? An Analysis of Greece's Dispute with FYROM",". 24 (1996) Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 285. Retrieved 2007-01-24.